Rep:Mod:XIR511

Experiment 1C

Part 1: Conformational analysis using Molecular Mechanics

The recent emergence of desktop modeling programmes, allowing for synthetic chemists and biologists to construct 3D structures of molecules and to perform a variety calculations and other actions to investigate their properties, has opened the doors to entirely new potentialities in scientific research. The purpose of this experiment is to make use of these advanced techniques, which have only become available to scientists in recent years. The two software programmes, which extensive use was made of in this experiment, are Avogadro and ChemBio3D Ultra. The programmes were used to explore the properties and interactions of molecules in 3D as well as to perform energy minimisation calculations on their structures. The HPC computing portal was used to simulate the NMR properties and optical rotatory power of the molecules in this investigation.

The Cyclopentadiene Dimer

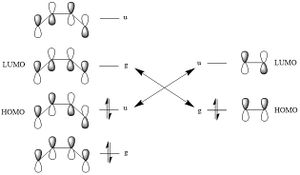

The aim of the first part of the experiment was to investigate the products formed in the dimerisation reaction of two cyclopentadiene (CPD) molecules. Depending on the approach of the two molecules in Diels-Alder fashion where one molecule serves as diene, the other as dienophile, there are two possible stereoisomers formed in theory: the exo- and the endo-dimer (Figure 1). Experimental evidence has shown that exclusively the latter is formed in the laboratory, this proceeds via a mechanism in which the unreacting double-bond of the dienophile is directed towards the diene (as opposed to being directed away from it, as is the case in the exo-dimer formation).[1] In order to determine whether this selectivity of dimerisation is due to thermodynamic or kinetic factors, both the exo- (1) and the endo-conformer (2) were investigated using ChemBio3D.

Using the MM2 force field option in a "minimum energy" calculation and repeatedly optimising the molecules' geometry to reduce bond strain, it was possible to compare the total energy of the two dimers.

| Property | Exo-Dimer (1) | Endo-Dimer (2) |

|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 1.2850 | 1.2509 |

| Bend | 20.5805 | 20.8477 |

| Stretch-bend | -0.8381 | -0.7609 |

| Torsion | 7.6555 | 9.5110 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.4174 | -1.5439 |

| 1,4 VDW | 4.2333 | 4.3201 |

| Dipole/Dipole | 0.3775 | 0.4476 |

| Total energy | 31.8764 kcal/mol | 33.9975 kcal/mol |

The tabulated results clearly show that it is indeed the exo-dimer which is more stable and thus thermodynamically favoured by being a total of 2.1211kcal/mol lower in energy. The values for the properties reported in the table correspond to deviations from ideality, i.e. the optimum value for each calculated function. Higher values therefore indicate a larger deviation from the fully optimised molecular structure. The stability of the exo-dimer mainly originates from lower torsional strain and Van der Waals strain.

- The 5-membered ring substituent is "anti" to the longer bridge, leading to less torsional strain than observed for the endo-dimer where the two rings are eclipsed.

- As a consequence of the eclipsed conformation, the Van der Waals repulsion between hydrogen atoms is larger for the endo-dimer.

This result strongly suggests that the Diels-Alder dimerisation of CPD is under kinetic control as only the endo-dimer is produced experimentally. The activation energy of the transition state leading to the formation of the molecule 2 must be sufficiently lower, facilitating a faster reaction. The stability of the intermediate transition state is due to stabilising effects of frontier molecular orbital interactions; the p-orbitals of the non-reacting double bond in the dienophile have the correct orientation to interact with p-orbitals of the dienophile. This stabilizing effect which decreases the energy of the transition state, is not given in the approach leading to the exo-adduct, where the non-reacting alkene is directed away from the approaching diene. Molecule 2 is thus the kinetic while molecule 1 is considered to be the thermodynamic product.

Hydrogenation of the Dimer

A similar analysis was performed on the dihydro derivatives 3 and 4 which are the two possible products formed in the initial hydrogenation of the endo-dimer. The reaction is regioselective, as either the norbornene or the cyclopentene is hydrogenated. A molecular mechanics calculation was performed as previously and allowed for an assignment of relative stabilities.

| Property | Dimer 3 | Dimer 4 |

|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 1.2348 | 1.0965 |

| Bend | 18.9380 | 14.5243 |

| Stretch-bend | -0.8349 | -0.5494 |

| Torsion | 12.1241 | 12.4974 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.5015 | -1.0700 |

| 1,4 VDW | 5.7289 | 4.5125 |

| Dipole/Dipole | 0.1631 | 0.1406 |

| Total energy | 35.9266 kcal/mol | 31.1520 kcal/mol |

The results clearly predict the hydrogenated dimer 4 to 4.7744kcal/mol lower in energy, primarily due to the molecule experiencing more ideal bending, stretching and van-der-Waals interactions (smaller deviation from ideality). Solely the torsional strain is greater in this dimer, which is due to the alkene being part of a 5-membered as opposed to a hexane ring. This agrees with the publication of Maier and Schleyer, who state that "olefinic strain (OS) is directly proportional to heats of hydrogenation"[2]. Relieving the bond strain of the cyclopentane ring thus requires larger hydrogenation energy, causing 3 to be the higher energy dimer. Dimer 4 exhibits higher stability and is hence the thermodynamic product. Literature agrees with the molecular mechanics prediction and reports 4 as the predominent product.[3] The hydrogenation of DCPD thus proceeds under thermodynamic control.

One of the key intermediates formed in the synthesis of the important anti-cancer drug taxol introduces the conformational phenomenon of atropisomerism. Atropisomers are stereoisomers characterised by hindered rotation about a single bond; the barrier to rotation is high and allows for separation of the two conformers at room temperature. Common examples include biphenyls and binaphthyls. Conformational atropisomers are therefore significant in the sense that the restricted rotation of certain bonds, due to angular strain, also leads to configurational isomerism.

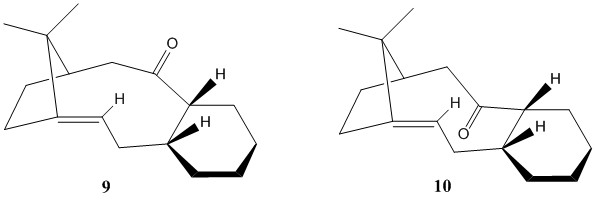

The two possible atropisomers of the taxol intermediate were first reported by Paquette [4] and are shown on the right as molecules 9 and 10.

Each molecule has in turn four conformational minima but significant population would only be expected from the thermodynamically most stable one; the one with lowest free energy value. The eight possible structures differ mainly in the conformation of the hexane ring as two chair and two twist-boat conformations exist for each molecule. Using ChemBio3D for an initial visual inspection of conformational stability, it appears that molecule 10 is more restrained due to the carbonyl "tucked under". This causes cyclohexane to be in closer proximity to the bridgehead methyl groups than is the case for any conformer of molecule 9. Total energy values for each of the eight conformations were obtained by using the MM2 force field calculation in ChemBio3D. A series of optimisations, in which the bond orientations were manually adjusted repeatedly, were performed to generate the lowest possible energy structures.

Results and Discussion

As a general observation it was found that chair conformations were always lower in energy than their respective twist-boats. This result was expected as the chair represents the lowest possible energy conformation for cyclohexane. The results obtained for the four molecules with the most stable chair conformations are shown below.

| Molecule 9(1) | Molecule 9(2) | Molecule 10(1) | Molecule 10(2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total energy | 47.8395 kcal/mol | 58.3858 kcal/mol | 42.6828 kcal/mol | 52.5418 kcal/mol |

The two lowest energy isomers were subsequently compared in order to derive at the most stable atropisomer.

| Property | Molecule 9 | Molecule 10 |

|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 2.7847 | 2.6205 |

| Bend | 16.5410 | 11.3391 |

| Stretch-bend | 0.4304 | 0.3432 |

| Torsion | 19.6723 | 19.6723 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.5521 | -2.1621 |

| 1,4 VDW | 12.8721 | 12.8721 |

| Dipole/Dipole | -1.7248 | -2.0023 |

| Total energy | 47.8395 kcal/mol | 42.6828 kcal/mol |

Contrary to the initial prediction, the molecular mechanics calculation clearly predicts molecule 10, with the carbonyl pointing down, to be more stable. Its energy is ~5.2kcal/mol lower, which is primarily due to a much lower bending energy. Atropisomer 10 thus benefits from less strained bond angles in the molecule. This result was verified through an inspection of the 3D Jmol images of both atropisomers, shown below. Whilst the carbonyl carbon in molecule 10 (right) exhibits optimal bond angles of ~120°, this is not achieved in molecule 9 (left) where the carbonyl C is locked into a conformation with a distorted angle of 125°.

Taxol9 |

Taxol9 |

Hyperstability

Another phenomenon characteristic to this taxol intermediate is that of hyperstable alkenes.[2] Hyperstability refers to the fact that olefins located at a bridgehead are thermodynamically stabilised and therefore unusually unreactive. by definition these olefins are less strained than their parent hydrocarbons. This phenomenon can be verified by calculating the olefinic strain (OS) in the molecule; this is achieved by subtracting the total strain energy of the most stable conformer of the parent alkane from the strain energy of the most stable olefin. The OS value is therefore directly related to the change in energy occurring in hydrogenation or other reactions. Since total strain energy is a composite of different properties, such as angular and torsional strain, the total energy provides a reasonable approximation and was therefore used to predict the OS for molecule 10 in comparison with its hydrogenated parent hydrocarbon. A comparison of key factors contributing to total strain are displayed in tabular form below.

| Property | Parent hydrocarbon | Molecule 10 |

|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 3.1495 | 2.6205 |

| Bend | 16.8578 | 11.3391 |

| Torsion | 22.3873 | 19.6723 |

| 1,4 VDW | 15.6115 | 12.8721 |

| Total energy | 56.5485 kcal/mol | 42.6828 kcal/mol |

The result clearly shows that the hydrogenated molecule is thermodynamically less stable than the bridgehead olefin; olefin strain can be quantified with -13.8657kcal/mol. A 3D representation of the serves to visualise the increased van der Waals repulsion between the two bridgehead methyls with hydrogens as well as the fact that the change in hybridisation from sp2 to sp3 results in unfavourable bond angles. It is therefore confirmed that intermediate 10 is a hyperstable alkene.

Spectroscopic Simulation using Quantum Mechanics

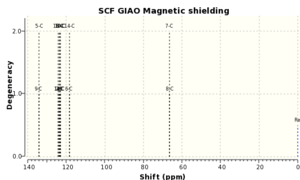

In the following part of the experiment, a spectroscopic simulation related to NMR spectra was envisaged. The objective of this exercise was to create simulations of 1H and 13C spectra for the molecules and subsequently compare the results to literature values in order to verify the validity of the latter. Predictions of each spectrum were simulated using the HPC system. This software allows for NMR spectra predictions within a few hours- again this represents a revolutionary scientific tool, not available to scientists only a few years ago.

Procedure

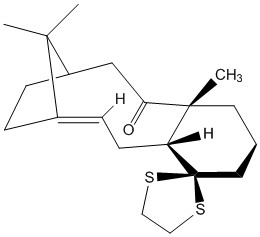

Before submitting the molecule to the HPC portal for spectroscopic simulation, the structure of the taxol intermediate was slightly modified by adding a methyl a well as a disulphur group. In addition it was decided to concentrate on a simulation of the molecule with carbonyl "tucked under" as this conformer was determined to be of lower energy previously (molecule 10). The fact that the relative energies for the derivatives of 9 and 10 remain unchanged upon addition of the two groups was verified using the ChemBio3D programme as well as being supported by literature[5]; the final molecule used in the simulation is shown on the left.

As before, different configurations for hexane were considered. Surprisingly, the lowest energy chair conformation was calculated to have 64.3641kcal/mol; making it 0.1984kcal/mol higher in energy than the most stable boat conformation. It was therefore decided to simulate the NMR spectra for both of these conformers in order to determine which structure gives a better match with literature.

The proton and carbon NMR spectra were run using chloroform as solvent and analysed using GaussView.

The spectral prediction was compared to literature values quoted by Paquette et al.[6] The quoted values for the proton NMR are based on a 300MHz spectrometer, using deuterated benzene as solvent, while 13C NMR was recorded using a 75MHz spectrometer and the same solvent. A comparison of the results is shown in table 5.

Comparison to literature values

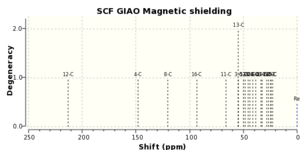

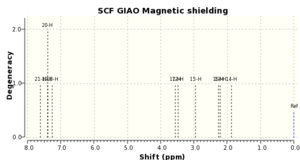

The 1H and 13C NMR spectra obtained from the HPC prediction[7],[8] are shown below.

| Calculated 1H chair | Calculated 1H boat | Literature values | Calculated 13C chair | Calculated 13C boat | Literature values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.99 | 5.26 | 5.21 | 213.05 | 210.68 | 211.49 | |

| 3.14-2.81 | 3.29-2.83 | 3.00-2.70 | 148.00 | 148.45 | 148.72 | |

| 2.61-2.33 | 2.51-2.34 | 2.70-2.35 | 120.22 | 119.01 | 120.90 | |

| 2.27-1.65 | 2.28-1.65 | 2.20-1.70 | 93.27 | 88.81 | 74.61 | |

| 1.58 | 1.57 | 1.58 | 65.93 | 67.95 | 60.53 | |

| 1.51-1.22 | 1.52-1.33 | 1.50-1.20 | 55.04-48.11 | 55.97-48.10 | 51.30-50.94 | |

| 0.95 | 1.15 | 1.10 | 45.80-44.15 | 44.14-42.07 | 45.53-43.28 | |

| 0.62 | 1.05 | 1.07 | 41.34-38.72 | 37.45 | 40.82-38.73 | |

| 1.02-0.93 | 1.03 | 33.71-32.57 | 35.29 | 36.78-35.47 | ||

| 28.41-26.51 | 31.02-28.69 | 30.84-30.00 | ||||

| 24.57-22.58 | 25.83-21.08 | 25.56-25.35 |

As a first observation it was noticeable that the predicted spectra show a significantly larger number of chemical shift values compared to literature values. In experiment, it is more difficult to differentiate between overlapping peaks which are almost degenerate. Overall, however, there is good agreement between computed and reported values for both nuclei. Discrepancies may be primarily due to the fact that there are four possible minimum energy conformers of the hexane ring (i.e. two chair and two twist-boats), making it impossible to know which isomer was investigated in the laboratory. In particular the reported proton NMR gave a better match with the boat conformation, suggesting that this might be the conformer for which literature values were quoted. Differences in the spectra should, however, be expected due to protons experiencing a change in environment upon conversion between conformers. This effect is not as strong for carbon NMR, as carbons remain in similar environments upon interconversion. The calculated and experimental carbon NMR spectra hence show a noticeably better match than the proton NMR spectra (vary within a 2ppm range).

Part 2

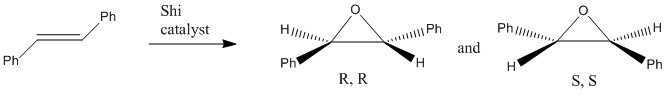

The aim of the second part in this experiment was to investigate the Shi and Jacobsen catalysts, both used in the asymmetric epoxidation of alkenes, as well as the epoxides formed from 1,2-Dihydronaphthalene and Trans-stilbene. The epoxidation reactions are considered to be enantioselective, meaning that only one of the two possible enantiomers is formed. The enantiomer formed is determined by the stereochemistry of the catalyst; the Shi catalyst is used in the epoxidation of trans-olefins whilst Jacobsen is catalysing the epoxidation of cis-alkenes. The objective is therefore to computationally assign the absolute configuration of the product formed based on an investigation of the following aspects: Catalyst structure, optical rotation, product NMR and interactions in the active site.

The crystal structures of the two catalysts

The two catalysts examined in this experiment are the Shi asymmetric Fructose catalyst (21) and the Jacobsen asymmetric catalyst (23). The exact structures were obtained using the Conquest Programme which is directly linked to the Cambridge crystal database (CCDB). Once Conquest detects the desired molecular structure in the system, the molecule can be viewed in Mercury, a programme used to display the crystal structures of molecules. The obtained Jmol 3D structures are displayed below.

Shiprecusor21 |

The first catalytic structure under investigation was the Shi catalyst (21). Using the 3D imagine from Mercury on this Wiki page allowed for a determination of bond lengths. In particular, the C-O bond lengths of the two anomeric centres in the molecule were compared as deviations from expected values suggest bond peculiarities. Equal lengths for both C-O bonds at an anomeric centre would be expected and this is indeed observed for the centre whose carbon is part of the cyclohexane ring (C-O lenths of 0.14nm were measured). The C-O lengths for the anomeric centre in the cyclopentane ring, however, are both longer and unequal. The measured lengths are 0.141nm and 0.144nm. This is due to the anomeric effect, where the heteroatom adjacent to an oxygen in a cyclohexane ring adopts the sterically unfavoured axial position. This allows for extra stability of the molecule as the oxygen lone pair (of ring-oxygen) can donate into the C-O anti-bonding orbital of the axial C-O bond. This effect causes the C-O bond length to be slightly longer than expected. Wang et al suggest that the ketals in the molecule activate and act as chiral control elements in the epoxidation of trans-olefins.[9] It is also suggested that the exact size and location of a chiral controlling element are important in terms of controlling the enantioselectivity. This shows that a proper balance of conformational, electronic, and steric effects for carbocyclic ketones is essential in ensuring desired reactivities and enantioselectivities. Its unique structure hence makes the Shi catalyst a perfect match for the asymmetric epoxidation of trans-stilbene, a reaction producing predominently the (R,R) enantiomer (ee: 97%).[9]

Shiprecusor21 |

Similarly, the 3D structure of catalyst 23 was used to analyse the close approach of two adjacent t-butyl groups on each aromatic ring. Literature describes this manganese(III) complex as highly suitable catalyst for enantioselective epoxidation of unfunctionalised olefins.[10] The t-butyl groups of the pentacoordinated structure are subject to large thermal motions, giving rise to a distorted square-pyramidal geometry. The distance calculated for the hydrogens on the t-butyl groups is 0.208nm and 0.258nm. The sum of van der Waals radii, i.e. the distance at which two atoms experience maximum attraction, is 0.24nm for hydrogens. This implies that the hydrogen interactions in the present molecule are partially repulsive. Further, an investigation of different bond lengths showed that the C=N bond is slightly longer than would be expected in an uncoordinated bond; 0.13nm compared to 0.127nm. The contrary is true for the C-O enol bond, which is calculated to be 0.132nm, making it 0.0043nm shorter than bonds in the free ligand. This observation is in agreement with literature which states the same trend.[10] This molecule provides the desired structure to catalyse the epoxidation of the cis-alkene 1,2-Dihydronaphthalene.

The calculated NMR properties of two asymmetric epoxidation products

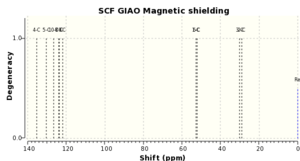

Following the same procedure as previously in part 1, calculated NMR spectra of the two epoxides were obtained by using the Gaussian extension in Avogadro. The simulated spectra for the epoxides formed from both 1,2 Dihydronaphthalene and Trans-stilbene were compared to literature values in order to verify that the expected products were actually formed.

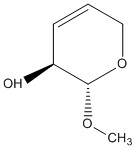

The first asymmetric epoxidation reaction considered in this experiment involved catalyst 21 in conjunction with 1,2-Dihydronaphthalene. Despite the fact that two possible enantiomers can form in the reaction, their respective energies and NMR spectra should be identical and hence the following results were obtained from simulating one enantiomer only.

The literature specified for 1H NMR is 400MHz CDCl3 and the 13C NMR is 100MHz CDCl3.[11]

| Calculated 1H | Literature values | Calculated 13C | Literature values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7.61 | 7.49 | 135.38 | 136.7 | |

| 7.39 (2H) | 7.38 (2H) | 130.37 | 132.6 | |

| 7.38 (2H) | 7.19 | 126.66 | 129.5 | |

| 7.25 | 123.79 | 128.4 | ||

| 3.55 | 3.59 (2H) | 123.53 | 126.1 | |

| 3.48 | 121.74 | 55.1 | ||

| 2.94 | 2.87 | 52.82 | 52.7 | |

| 2.26 | 2.26 | 52.19 | 24.4 | |

| 2.20 | 2.21 | 30.18 | 21.8 | |

| 1.87 | 1.56 | 29.06 |

From table 6 it is apparent that the simulated 1H and 13C NMR spectra[12] provide a close match to literature. The computed chemical shifts for proton nuclei are within a 0.2ppm range of reported values while the carbon spectra show correspondence within 8ppm. The strong correlation indicates that indeed the right epoxide has been modeled in Avogadro.

Secondly, the epoxidation of trans-stilbene leading to the formation of trans-2,3-diphenyloxirane when catalysed by the Shi catalyst 23 was investigated.[13] Again, only one of the two possible (R,R or S,S) enantiomers was simulated. The literature for 1H NMR is 400MHz CDCl3 and there was no reliable data on 13C NMR found.

| Calculated 1H | Literature values | Calculated 13C | Literature values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7.57-7.45 (68H) | 7.42-7.32 | 134.08 | ||

| 3.53 (4H) | 3.87 | 124.21 | ||

| 123.51-123.07 | ||||

| 118.26 | ||||

| 66.42 |

As before, the literature [14] comparison showed strong correlation between the proton NMR values within a range of 0.3ppm.

This comparison does, however, not allow for an assignment of the absolute configuration for either epoxide since the spectra for two enantiomers are always identical. It's sole purpose is thus to verify that the right epoxide was indeed modeled computationally.

Assigning the absolute configuration

Optical rotations: Comparison between calculated and literature values

In order to assign an absolute configuration to each of the two epoxides, it was decided to calculate the optical rotation for the two enantiomers modelled in Avogadro. The two molecules were determined to be 1R,2S-1,2 Dihydronaphthalene oxide and (R,R)-trans-stilbene oxide. The optical rotation of both molecules was then simulated in HPC, using the optimised log-file, and the result was subsequently compared to literature in order to test the validity of the latter.

The calculated optical rotations were extracted as Gaussian log-file and the results are tabulated below. Again, this procedure was performed for one of two possible enantiomers only, as equal and opposite values for each enantiomeric pair can be assumed. The calculations were performed using an incident wavelength of 589nm.[15]

| Alkene | Calculated value (589nm) | Literature value (589nm) |

|---|---|---|

| R,S 1,2-Dihydronaphthalene oxide | 35.86° | 38° |

| (R,R) Trans-stilbene oxide | 297.75° | 250.8° |

The values for ORP quoted in literature were unfortunately rather insufficient and inconsistent. Measurements were conducted in a variety of different conditions or even varied within a set of conditions. An attempt at a conclusive comparison was made by referencing the most frequently stated value for both enantiomers. For 1,2-dihydronaphthalene oxide, literature quotes the (1S, 2R) enantiomer to be formed with >99% selectivity, having an optical rotation of -38 degrees. ORP is therefore an unreliable tool for the assignment of the absolute configuration of epoxides.

Calculated properties of the Transition State for β-methyl styrene

Computing the transition state of a reacting system and using the result to identify the exact stereochemistry of the catalyst and olefin during epoxidation, is the most reliable procedure leading to an assignment of absolute configurations in asymmetric epoxidations. This procedure was followed for the Shi catalysed epoxidation of β-methyl styrene. A comparison of the relative free energy values (corrected for entropy and zero-point thermal energies) of the transition states was performed in order to identify the lowest feasible energy pathway. Overall, there are eight different transition states possible in this epoxidation, though it was assumed that the reaction proceeds through the lowest energy transition state. The change in energy for interconversion from the (R,R) to the (S,S) enantiomer was determined, this allowed for a subsequent calculation of K, the ratio of concentrations of the two species: ∆G=-RTln(K).

- ∆G=20.218977 kJ/mol

- K= 2.8681*10-4

Both the fact that ∆G is positive, i.e. non-spontaneous reaction, and the small value of the equilibrium constant indicate that the interconversion from the (R,R) to the (S,S) enantiomer is unfavourable. (R,R) β-methyl styrene oxide should therefore in theory be the major epoxide formed. The enantiomeric excess was calculated to be ee: 99.97%.

Since the transition states for neither of the two alkenes considered in this investigation were available, the above analysis has to be used as an approximation for the trans-olefin. Following from this analysis, trans-stilbene would produce its (R,R) enantiomer in enantiomeric excess. According to literature values from Wang et al. this is indeed the case and a similarly high ee value was quoted (97%).[9]

Investigating the non-covalent interactions in the active-site of the reaction transition state

The outcome of enantioselective reactions is directly dependent on the structure of the transition state. The interaction between a catalyst and the reacting species can be subjected to a NCI analysis (non-covalent interactions); this was performed on the 4th (R,R) transition state in the Shi epoxidation of β-methyl styrene. Non-covalent-interactions involve any bond-like interactions between atoms, such as hydrogen bonds, electrostatic and dispersion interactions. Electron density computations therefore aid in the identification of these interactions and provide information about the stereoselectivity of the system. The computed energy surface model is shown below. (Colour coding is as follows: Blue=strongly attractive, green=mildly attractive, yellow=mildly repulsive and red=strongly repulsive)

Orbital |

As for the catalyst, the diagram suggests a large number of mildly attractive interactions between methyl-hydrogens on the two cyclopentane rings and oxygen atoms in the catalyst. These originate most likely from hydrogen bonding; the carbonyl group on cyclohexane is stabilised in this fashion from two different sides. A clutter of similar mildly attractive interactions is observed for the terminal methyl hydrogens on β-methyl styrene as well as for the hydrogen on the reacting alkene group, both interact with the anomeric oxygen atoms in the catalyst. Both of the cyclopentane rings in the Shi catalyst experience ring strain as indicated by the red (strongly repulsive) energy surfaces within the rings. Besides bond strain this may be due to repulsion of the oxygen lone pairs. As would have been expected, the two cyclohexane rings in the system are less strained and thus exhibit only mildly repulsive energy surfaces. The diagram also confirms that it is indeed the carbonyl carbon in the cyclohexane ring of the catalyst which is oriented closest towards the olefin in trans-β-methyl styrene.

Investigating the Electronic topology (QTAIM) in the active-site of the reaction transition state

Conducting a NCI analysis is complementary to an investigation of the electronic topology of a reacting system: In addition to non-covalent interactions, the QTAIM also depicts actual bonds in the system, based on varying degrees of electron density in covalent regions. The diagram obtained from subjecting the a (S,S) β-methyl styrene transition state (second in the sequence) to QTAIM analaysis, yielded two different types of bond critical points (BCP): Weak non-covalent interactions, denoted by a dotted line, and covalent bonds, displayed by solid lines. Critical points occur where the first derivative of electron density is zero, meaning that it is at a maximum. For bonds between identical atoms the critical point lies exactly in the middle of the bond, which is where the interaction is strongest due to equal electronegativity values. Arrow 1 in the diagram points to the covalent interaction between to carbon atoms. A non-covalent interaction can be observed between the oxygen in cyclohexane and a methyl hydrogen atom (arrow 2). These interactions would, however, be expected and are thus not unusual. A more interesting BCP is shown by arrow 3; the carbonyl on the catalyst starts to form non-covalent interactions with the olefin bond on the reactant. This method thus allows for an advanced reconstruction of the stereochemistry of the transition state whilst explaining the enantioselectivity of the reaction.

New candidates for investigations

The last task in this investigation was to identify an olefin suitable for a similar investigation as performed on both 1,2 Dihydronapthalene and trans-stilbene above. A possible candidate for investigation would be methyl 3,4-anhydro-β-L-ribopyranoside. It is commercially available and compatible with a variety of enantioselective catalysts. It is only the asymmetric epoxidation of unfunctionalized olefins which constitutes a challenge to organic synthesis. The array of effective and available methods for epoxidation of cis-olefins make this class of molecules a suitable choice in the attempt to assign absolute configurations to enantiomers. The optical rotatory power of the molecule is quoted as 542.8 degrees (589nm).[18]

References

- ↑ P. Caramella, P. Quadrelli, L. Toma, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2002, 124, 1130. DOI:10.1021/ja016622h

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 W. F. Maier, P. Von Rague Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103, 1891. DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ G. Liu, Z. Mi, L. Wang, Z. Zhang, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2005, 44(11), 3846-3851. DOI:10.1021/ie0487437

- ↑ S. W. Elmore and L. Paquette, Tetrahedron Letters, 1991, 319; DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0

- ↑ L. Paquette, K. Combrink, S. Elmore, R. Rogers, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1991, 113(4), 1335-1344. DOI:[1] 10.1021/ja00004a040

- ↑ L. Paquette, N. Pegg, D. Toops, G. Maynard, R. Rogers, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1990, 112(1), 277-283. DOI:[2] 10.1021/ja00157a043

- ↑ Insa Roemgens Molecule 18 (chair)http://hdl.handle.net/10042/25855

- ↑ Insa Roemgens Molecule 18 (boat) http://hdl.handle.net/10042/25856

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Z. Wang, S. Miller, O. P. Anderson, Y. Shi, J. Org. Chem., 2001, 66(2), 521-530. DOI:10.1021/jo001343i

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Y.W. Yoon, T. Yoon, S. W. Lee, W. Shin, Acta Crystallographica, 1999, 55(11), 1766-1769. DOI:10.1107/S0108270199009397

- ↑ K. Smith, C. Liu, G. El-Hiti, Org. Biomol. Chem., 2006, 4, 917. DOI:10.1039/B517611P 10.1039/B517611P

- ↑ Insa Roemgens 1,2 Dihydronaphthalene oxide http://hdl.handle.net/10042/25857

- ↑ Insa Roemgens Trans-stilbene oxide http://hdl.handle.net/10042/25858

- ↑ K. Stingl, K. Weiss, S. Tsogoeva, Tetrahedron, 2012, 68(40), 8493. DOI:10.1016/j.tet.2012.07.052 10.1016/j.tet.2012.07.052

- ↑ ORP epoxides http://hdl.handle.net/10042/25859, http://hdl.handle.net/10042/25860

- ↑ H. Lin, J. Qiao, Y. Liu, Z. Wu Journal of Molecular Catalysis, 2001, 67(3), 236-241. DOI:10.1016/j.molcatb.2010.08.012

- ↑ D. Fox, D. Pedersen, A. Petersen, S. Warren, Org. Biomol. Chem., 2006, 4, 3117-3119. DOI:10.1039/b606881b

- ↑ N. Mohal, A. Vasella Helv. Chim. Acta, 2005, 88, 100-119. DOI:10.1016/j.tet.2012.07.052 10.1016/j.tet.2012.07.052