Rep:LS:FHT14

Prediction of Thermodynamic Properties of the Lennard-Jones Fluid via Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Felix Henry Thompson – 00930702 – 28th March 2018

Abstract

This work sought to demonstrate that Molecular Dynamics calculations on medium-sized (4000 atom) systems could provide the quick determination of various thermodynamic trends present in the Lennard-Jones fluid. Overall this attempt was successful, demonstrations of system equilibration, gas density, heat capacity, and diffusivity, were all able to be made using calculations taking less than five minutes to complete. This work also demonstrates the effect of time-step and system size on the precision and stability of computed values.

Introduction

Molecular Dynamics was first conceptually described in the 1950s, not seeing general use until the mid-1970s.[1] As a technique, it sought to confront the age-old difficulty of solving the N-body problem — how could one evaluate how a large system of bodies develops through time? It was the advent of accessible computing which provided the work-power needed to resolve this problem. With modern personal computing power, as well as access to specialised computing facilities, systems containing thousands of bodies can be evaluated, with results being presented in seconds and minutes, rather than weeks and months.[2]

Originally Molecular Dynamics was only being applied to small, well-defined, near-theoretical, systems such as perfect hard-spheres, or point-masses with simplistic interparticle interactions. In stark contrast to this, MD nowadays sees major applications to the dynamics of proteins and other biological systems.[3] Compared to the original systems, these new ones are full of complex degrees of freedom, huge varieties of interparticle forces, variable responses to potentials, and potentially involving proteins kDa's in size. This area is of great interest, due to the dynamics of proteins underpinning their biological action. As such, competent understanding of them may allow the directing of new medicines and pharmaceutical techniques.[4]

The basic structure of Molecular Dynamics is fairly simplistic in principle — we evaluate the force on each particle in our system (often neglecting the majority of pair interactions), use that to determine the acceleration, propagate the particles some small distance in time, update the new positions and velocities, and then repeat as needed. There are a wide variety of methodologies that allow one to put this process into practice. The simulations in this work follow the Velocity–Verlet algorithm, explanations of which can be found [2,5].

The forces between particles in your system define the properties that system will have. In this work the Lennard-Jones potential is used, defined in Eq. 1.[6] As such we are modeling the Lennard-Jones fluid, the phase diagram of which is also provided in Fig. 1.[2,7,8] Throughout this work, it is our goal to navigate the thermodynamic properties of this system using the tools of Molecular Dynamics.

Aim and Objectives

This project seeks to demonstrate trends in various thermodynamic and structural responses to conditions, as well as trends in the results of simulations based on the way these calculations are set up. The areas covered in this investigation are summarised as follows:

- 1 – How does the value of the time-step effect equilibration of a system's properties?

- 2 – How do simulated densities compare to values predicted by the ideal gas law, and what are the trends seen by varying pressure or temperature?

- 3 – What are the trends seen in the volume-specific heat capacity with respect to temperature? How do these trends vary for different densities?

- 4 – How does the radial distribution function vary dependent on phase?

- 5 – Investigating Mean Squared Displacement and diffusivity for differing phases

Methods

Throughout this work all simulation calculations were performed on Imperial College London's High Performance Computing service, using LAMMPS.[9] VMD was also used in visualising and analysing the results of said calculations.[10] All further analysis was performed utilising the Python programming language, with project code provided where relevant.[11] All calculations use a Lennard-Jones force-field for uncharged point masses, with a cut-off at 3 or 3.2σ. This potential was used as it is not too computationally intensive, with a cut-off that still captures the majority of significant interactions whilst reducing the number of pairwise interactions to calculate. Unless stated otherwise, all reported values are in Lennard-Jones reduced units.

The first investigation sought to demonstrate the connection between how a system equilibrates its thermodynamic properties based on the size of the time-step between calculations. The simulations functioned by first populating a simple cubic lattice with 1000 atoms, giving these atoms velocities corresponding to a reduced temperature of 1.5, shifting to the nve microstate, and then measuring the energy, temperature, and pressure over the course of 100 reduced time units. Different values of time-step were tested, 0.015, 0.01, 0.0075, 0.0025, and 0.001. An example input file is provided here(here), provided by Imperial College London.

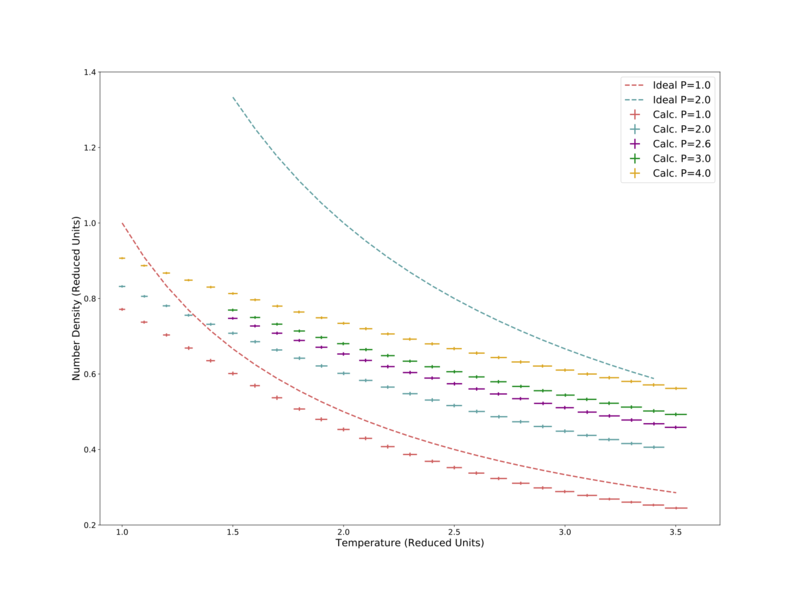

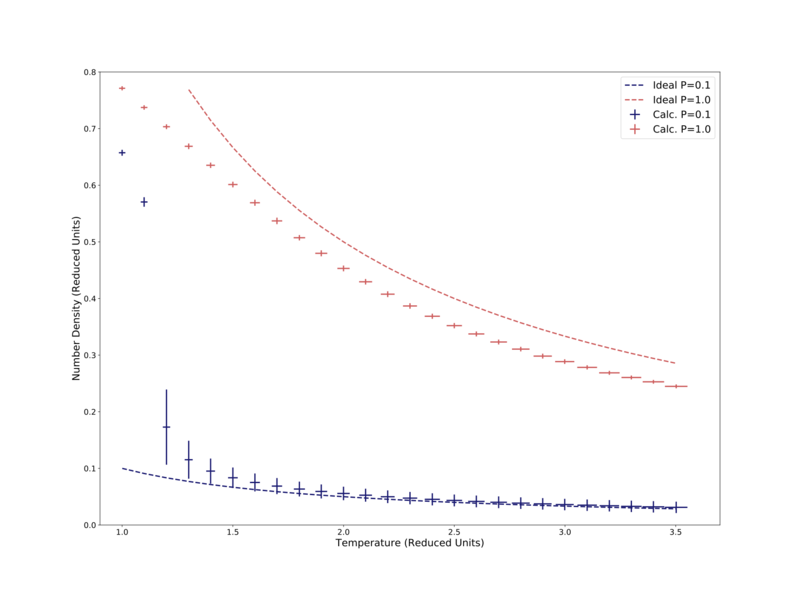

An investigation of density with respect to temperature for the pressures 1.0, 2.0, 2.6, 3.0, 4.0. Temperatures were set from 1 to 3.5. These simulations took place within the NpT ensemble, providing the average pressure, temperature, and density of simulated systems. The process for creating the system is structurally the same as above, although it simulated a larger system of 3375 atoms and used a 0.001 time-step. An example input file is provided here (here), provided by Imperial College London.

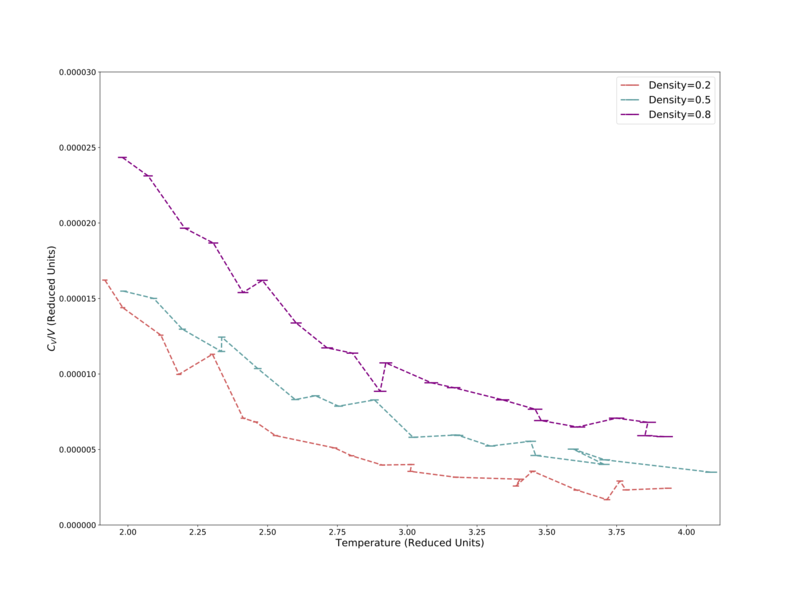

Code from the above simulation was adapted to shift to the NVT ensemble, allowing the determination of the volume-specific heat capacity. The simulation functions again by first creating and melting a crystal, bringing it to the desired density and temperature in the NVT ensemble, and then measuring the properties of the system over 100000 steps, with a time-step of 0.001. Resulting averages allow the determination of the volume-specific heat capacity, as seen in Eq. 2. These simulations were performed for the densities 0.2, 0.5, 0.8 the temperature range 1.0–4.0. An example input file is provided here (here).

Using similar code to the first investigation (bar the exclusion of the nve microstate, a larger Lennard-Jones cut-off of 3.2σ, a larger time-step of 0.002, and the ability to change temperature) the trajectories of the particles was measured. Using VMD, the trajectories were then visualised, and the Radial Pair Distribution Function g(r) extension allowed the determination of the Radial Pair Distribution and its corresponding integral. Using temperatures and densities corresponding to different phases of the Lennard-Jones fluid[2,7,8], the behaviors in differing phases was analysed. An example input file is provided here (here), provided by Imperial College London.

Lastly the Mean Squared Displacement for different phases of the Lennard-Jones fluid were analysed. A larger 8000 atom system was used, again using a Lennard-Jones force field with a 3.2σ cut-off distance. The system is melted to the required temperature, equilibrated for 10000 steps, and then the Mean Squared Displacement was determined for a subsequent 5000 steps. An example input file is provided here (here), provided by Imperial College London.

Results and Discussion

Effect of Time-Step on Equilibration

Firstly, brief analysis was performed on the effect of time-step size on the equilibration of a system. To do this, five versions of the same system — 100 reduced time units for a 1000 atom system at a reduced temperature of 1.5 — were simulated with different time-steps: 0.015, 0.01, 0.0075, 0.0025, 0.001. Every 10 timesteps the total energy was reserved, and is plotted against reduced time below in Fig. 2.

It is clear that the 0.015 time-step never converges to an equilibrium state, its energy continues to rise and rise — violating energy conservation. This likely occurs as the time-step is large enough that atoms move far enough per time-step that they end up located unrealistically close to each other, producing a corresponding high repulsive force and raising the system's energy. In comparison the four shorter time-steps all do converge quickly (within a few steps) to a stable value. Over time these systems do deviate about their converged value, but overall there is no net movement away from it. It is noted that the smaller the time-step, the lower the total energy. Again this will be due to larger time-steps moving closer to each other than is realistic. The smaller deviation about a converged value for smaller time-steps can be understood similarly.

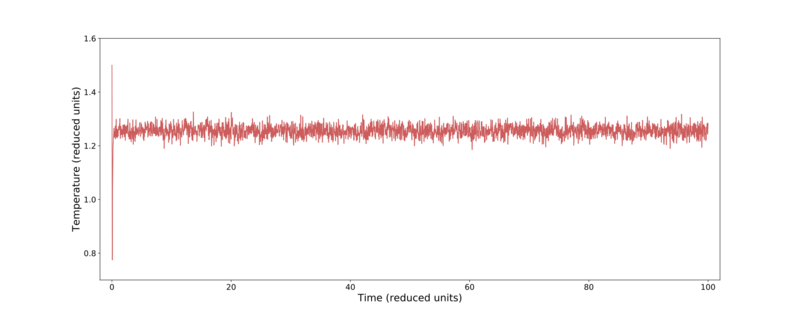

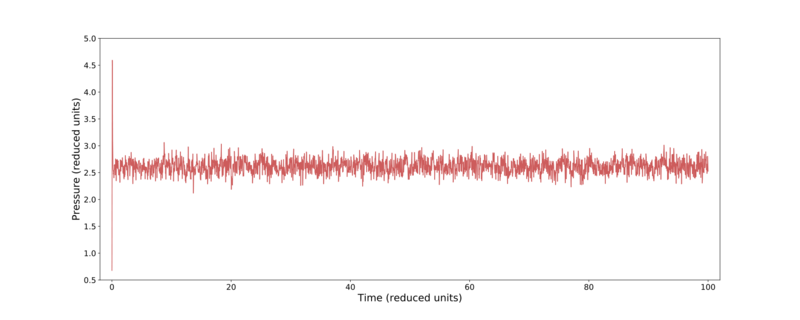

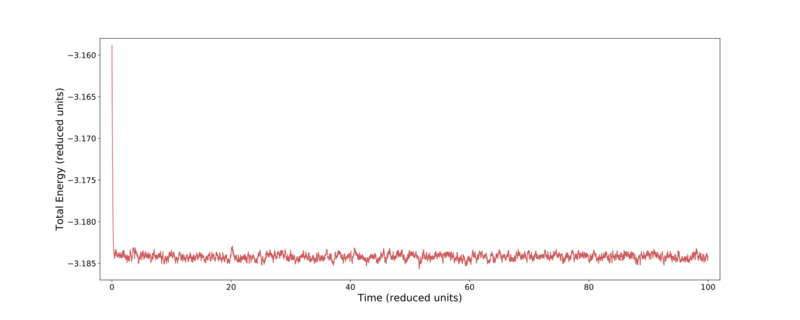

From Fig. 2 it is clear that the most successful time-steps are the 0.001 and 0.0025. Due to these calculations only taking a relatively short time for either time-step, the smaller value was preserved for later use. Fig. 3–5 shows further thermodynamic information over the course of the 0.001 time-step simulation. Here it can be seen that the temperature, pressure, and total energy all converge within a short number of time-steps.

|

|

|

Plotting the Equation of State

Here a variety of pressures were chosen, for each of which the number density was determined for the range of temperatures = 1–3.5. The standard errors in temperature and density were recorded, and are displayed in Fig. 6. Here it can be seen, as expected, that density decreases with temperature (atoms have more kinetic energy so spend more time further apart). It is also noted that the standard error in temperature increases with temperature, this is likely due to the particles moving faster and as such can move to less realistic positions. Decreasing the size of the time-step would decrease this error.

Also plotted in Fig. 6 are the Ideal Gas Law predictions of the number density for the two lowest pressures, 2.0 and 1.0. The higher pressure attempt does not fit well to the calculated data, largely sitting more than 50% above it. The lower pressure attempt shows the same shape in temperature response, but again sits some distance above the calculated data. The simulated density is lower than the Ideal Gas Law, likely due to the simulation including interparticle interactions — the Lennard-Jones potential largely prevents two particles from being less than 1σ apart, whereas in the Ideal Gas Law particles are assumed to not interact and therefore can get as close together as needed. It is noted that the calculated data better approached the Ideal Gas Law at low pressure and high temperature, the same conditions at which the law is most applicable. To further demonstrate this relation, calculations were performed at a significantly lower pressure: 0.1 reduced pressure units. This data is compared to the corresponding Ideal Gas Law prediction, as well as the 1.0 pressure data from the previous figure, in Fig. 7. Here the data well matches the Ideal Gas Law. The calculation also better shows the effect of crossing the critical temperature = 1.5, where the number density suddenly increases significantly, as well as the standard error in density. This effect is due to the system moving from the fluid phase to the liquid phase.

Calculating Heat Capacity

Here the volume-specific heat capacity, calculated via Eq. 2, was determined for three reduced number densities 0.2–0.8, over the reduced temperature range 1–4. Fig. 8 below shows the volume-specific heat capacity (normalised by dividing by the volume of the simulation cell) over the later temperatures, 2–4. Here all three different densities are in the supercritical fluid phase, with the lowest density fluid having the lowest heat capacity, and all show the trend of decreasing normalised volume-specific heat capacity with increasing temperature. The former can be justified by the fact that it is easiest to change the temperature of a low density material – there is less matter to absorb energy. The latter trend could be thought of as being due to each fluid becoming less dense with increasing temperature, but by looking back to the ideal gas we can picture this differently.

Heat capacity is related to the gradient of the internal energy vs temperature diagram. As the fluids become hotter and hotter, they also become less dense. We remember from earlier that hot, low-density gasses have properties that approximate the ideal gas. The internal energy of an ideal gas is singularly defined as , making its increase linear with respect to temperature. As such the internal energy vs temperature gradient move closer and closer to a constant value () as the fluid approaches ideal behavior, shown in Fig. 8 by the lines all decreasing and beginning to plateau off.

Fig. 9 shows the earlier temperature range, 1–1.3. Here the 0.8 density plot remains reasonably level compared to the other two densities. Their heat capacities increase rapidly below approximately 1.2 reduced temperature units. Looking back at the Lennard-Jones phase diagram in Fig. 1, this is clearly due to their transitioning into the vapour-liquid coexistence phase — the heat capacity of a liquid being much higher than a gas.

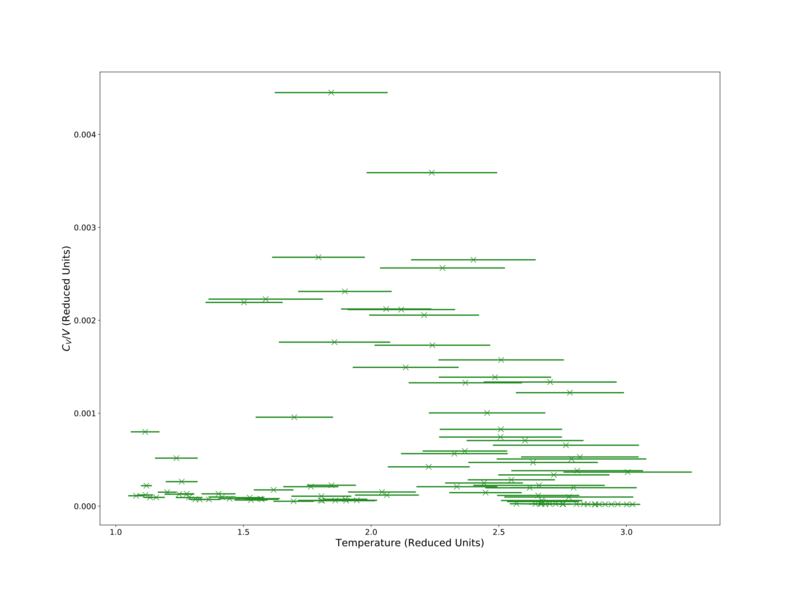

It is noted that as density increases the apparent error in increases as well. This will likely be a result of errors propagating from the velocity into the total energy, which itself is magnified in the calculation of , which also involves the error in temperature as well. This high error is typified in an attempt to analyse the number density = 1.3 system, shown in Fig. 10.

Radial Distribution Function for Differing Phases

Here temperatures and densities were selected to give system in the solid, liquid, and vapour phases. The trajectories of these systems were measured, and passed to VMD to allow calculation of the Radial Distribution Fuction g(r) for each system. The integrals of this function were also calculated. The RDF for each phase is given in Figs. 11–13.

The RDF for the solid is complex, yet well structured. Here each peak corresponds to a lattice point some distance away from another point. The first three peaks are at reduced distances of 1.025, 1.475, and 1.825. Therefore for the argon system these distances correspond to 349, 502, and 620 pm. An experimentally determined lattice parameter for the argon crystal is a=525.6 pm.[12] This gives rise to the first three nearest lattice points being , equal to 372, 526, and 643 pm. These values are approximately equal, varying by ca. 20 pm, demonstrating that the lattice spacings can be approximately determined by evaluating the RDF.

The RDFs for the liquid and vapour phases are similar, they both have a peak at approximately 1σ, they oscillate with a period of 1σ, with the gas RDF decaying much faster. This is explained by the high density of a liquid, meaning that a large number of particles are found within a few σ of each other, whereas a gas is diffuse and therefore has few nearby particles. The peak around 1σ for the gas is explained by the fact that when two gas particles collide, they decelerate before beginning to move away from each other. This results in colliding particles spending a significant amount of time about 1σ apart, giving rise to the aforementioned peak.

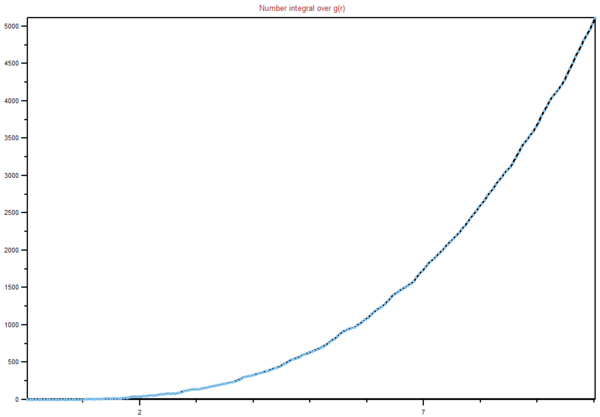

The integrals of the RDFs are also included for the three phases as Figs. 14–16. Here the number integral is given from 0–7σ. The graphs for the solid and gas appear as expected — an exponential increase in number integral over distance. The integrals show that the more atoms are present within 10σ for the solid than within the gas, about 5100 vs 1750. This is just down to the higher density of the solid. The graph for the liquid is more complex, it begins by increasing exponentially, but then begins to tail off after approximately 8σ. This can be explained by a finite size error — the sphere it is integrating over begins to extend past the walls of the simulation volume, which is approximately 16σ side-to-side

Mean Squared Displacement for Differing Phases

Here temperatures and densities were selected to give systems in the solid, liquid, and vapour phases. On these systems the Mean Squared Displacement was calculated. From this data a value for the diffusion coefficient was calculated between each adjacent pair of values. From this the development of the diffusion coefficient over time could be analysed.

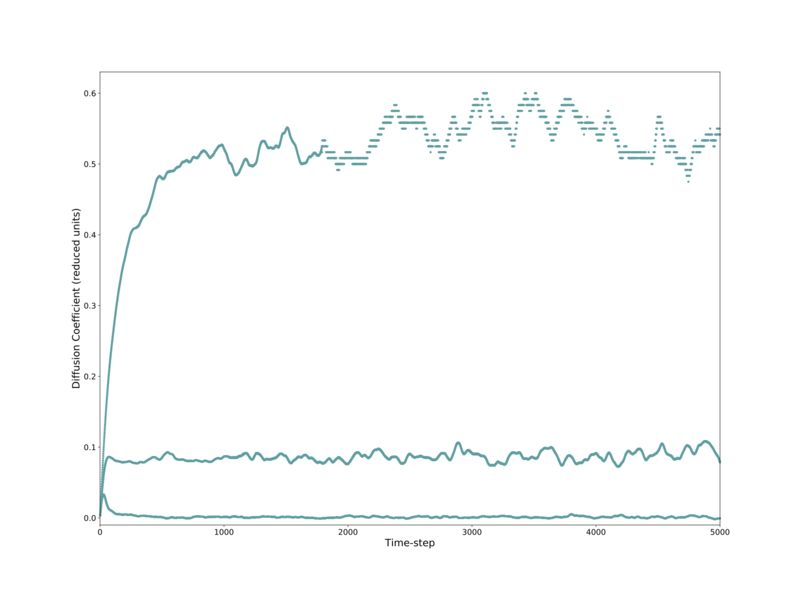

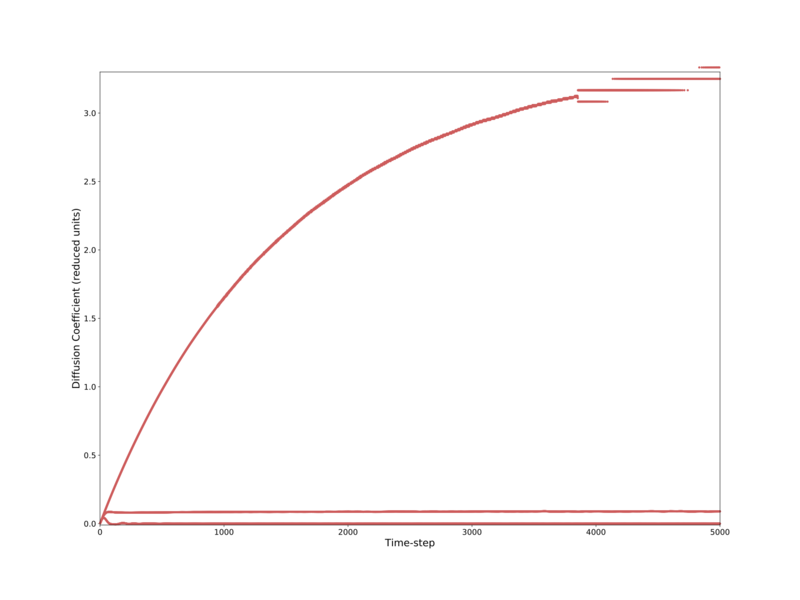

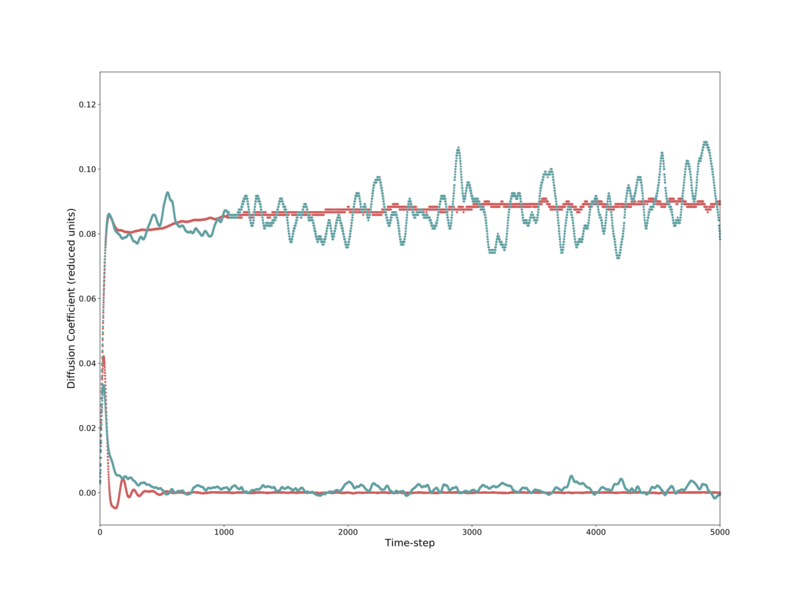

For the solid phase, the diffusivity initially oscillates significantly about zero, before converging to it. The liquid phase's diffusivity initially climbs rapidly, before roughly plateauing out after 30–40 time-steps. The gas phase behaves similarly, but takes longer to plateau, and reaches a higher value. These three systems, shown in Fig. 17, although leveling out, continue to have significant deviations at the end of the simulation.

Similar analysis was performed on a provided set of data for systems containing approximately 1000000 atoms, compared to the above 8000 atom systems. Here identical trends are seen in the general shape for each phase, with the curves being significantly smoother and less erratic. The exception is that the gas phase does has not plateaued after 5000 steps, and is still increasing — albeit at a decreasing rate. These trends are shown in Figs. 18–19.

For the solid phase we expect the diffusivity to eventually settle to zero, as the system arranges itself into a perfect crystalline lattice. In a perfect lattice, comprised of only a single atom type, there can be no diffusion. As such the diffusivity is zero. For the liquid and gas phases, the systems originally start on lattice points, but then are free to move about and equilibrate as fluids. Atoms in a liquid move more slowly and are closer together, so the system equilibrates faster than a gas. Our smaller gas system equilibrates faster than the larger gas system, likely due to it being faster to distribute energy (and therefore equilibrate) across a smaller system. Obviously the diffusivity is larger for a gas than a liquid due to the atoms moving faster with less hindrance on their motion.

Conclusion

Overall this work well represents an introduction into the modeling of thermodynamic trends for the Lennard-Jones fluid by using Molecular Dynamics. The calculations contained herein required little time in both their formulation and completion, rendering these simulations viable methods for quickly sketching out key thermodynamic features. Molecular Dynamics calculations have proven themselves suitable methods for simulating across a variety of phases, as well as showing the expected shifts in properties as the system transitions between phases. For more accurate versions of the above calculations, decreasing the time-step and increasing the size of the system would suffice, but the work of this report demonstrate that even with relatively small systems (3000 atoms), key properties and trends can be determined with ease.

It would be of interest to further examine exactly how far these calculation methodologies can take us in describing the Lennard-Jones fluid. Quantitatively mapping out the phases of the Lennard-Jones temperature-density space would be a strong demonstration of this methods ability to describe phase transitions as well as the phase-coexistence regions, with time-constraints not allowing such an attempt at present. Little attempt has been made in this work to compare the results of calculations with physical experimental results, which is ultimately the real test of a simulation's capabilities. Work should also be completed to compare the capabilities of the Lennard-Jones force field with those of more recent models.

References

- [1] – B.J. Alder and T.E. Wainwright, J. Chem. Phys., 1959, 31

- [2] – J.M. Haile, Molecular Dynamics Simulation: Elementary Methods, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, 1997

- [3] – A. Hospital, J.R. Goni, M. Orozco, and J.L. Gelpi, Adv. App. Bioinf. Chem., 2015, 8, 37–47

- [4] – L. Yang, P. Sang, Y. Tao, Y. Fu, K. Zhang, Y. Xie, and S. Lie, J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn., 2014, 32, 372–393

- [5] – W.C. Swope, H.C. Andersen, P.H. Berens, and K.R. Wilson, J. Chem. Phys., 1982, 76, 637–649

- [6] – M.P Allen, Compuational Soft Matter: From Synthetic Polymers to Proteins, Lecture Notes, N. Attig, K. Binder, H. Grubmuller, and K. Kremer (Ed), 2004, pp.1–28, 3-00-012641-4

- [7] – J.J. Nicolas, K.E. Gubbins, W.B. Streett, and D.J. Tildesley, Mol. Phys., 1967, 37

- [8] – J.P. Hansen, and I.R. McDonald, Theory of Simple Liquids, 1st Ed, Academic, London, 1976

- [9] – S. Plimpton, J. Comp. Phys., 1995, 117, 1–19

- [10] – W. Humphrey, A. Dalke, K. Schulten, J. Molec. Graphics, 1996, 14, 33–38

- [11] – Python Software Foundation, Python Language Reference, version 3.0. Available at http://www.python.org

- [12] – D. G. Henshaw, Phys. Rev., 1958, 111, 1470

Supplementary Materials

- Intro example input

- NpT example input

- Cv example input

- RDF example input

- Diffusivity example input

- Ho.xls showing working

Tasks

For many of the tasks there was little connection between their results and/or content with discussions made in the main body of this report, and I did not want this to prevent my going into depth when tackling them. As such all tasks are listed below, with those not discussed in the main body of this report gone into detail below. Areas where attention has been paid in the main body are not discussed below, so as to avoid unnecessary duplication of statements.

Velocity–Verlet work on HO.xls

Provided to us was an .xls file containing an implementation of the Velocity–Verlet algorithm to the Simple Harmonic Oscillator (SHO). We were required to extend this work to calculate the position with respect to time for a classical SHO (), the error in position between the classical and Velocity–Verlet modellings, and the energy of the Velocity–Verlet oscillator. This work is available as the provided .xls file (here).

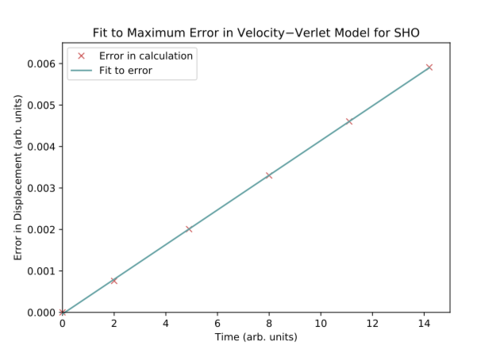

Once the above work was completed we were then tasked with investigating the connection between error in position with respect to time. For the time-step 0.1 the error can be seen to oscillate over course of an oscillation — approximately equal to zero when displacement was maximised. An approximate value of error and time was taken for the five maxima seen in the first 15 time units. This was then fitted to a straight line, as shown in Fig. 20, alongside the residuals for this fit. This fit shows good agreement with the initial values with no discernible trend in the residuals. However, as this only contains 5 points, it can hardly be called conclusive.

|

|

If we increase the simulation time to be much larger than 14.2 we can see that this linear relationship continues. If we then begin to increase the size of the time-step, more complex features of this plot begin to emerge as the errors become more significant. For a time-step of 0.55 it can be seen that there is a periodic trend in the error. This can be explained by the fact that the Velocity–Verlet oscillator lags behind the classically modeled oscillator, and that eventually it lags so far behind that it is half an oscillation behind the classical oscillator. Once it reaches this point its lagging behind actually serves to decrease the error in position, until it eventually catches up again — an error of 0. At even higher time-steps, even more complex features can be seen ‐ likely due to the differing errors in estimating position and velocity in the Velocity–Verlet algorithm.

We were also tasked with analysing the deviation in total energy of the Velocity–Verlet-modeled oscillator. For a SHO, the total energy is equal to the kinetic energy plus the potential energy (Eq. 3), and is constant over time. As in the Velocity–Verlet oscillator there is an error in both velocity and position, we expect the total energy to deviate over time. The total energy vs time for the Velocity–Verlet with time-step equal to 0.1 changes in energy by up to 0.25% over the course of the simulation. By varying the time-step it was found that a value of approximately 0.2 would give a maximum change in energy of 1%.

It is important to monitor the total energy over the course of a simulation as it is a value which we expect to be conserved. As such any observed deviation from the initial value is demonstrative of the fact that the simulation is falling short in some fashion. Equally one can then use this to optimise simulation accuracy vs computational time — a shorter time-step means that it will take more calculations to simulate the same period of time, but will ensure that the accuracy is better.

Atomic Forces

We were tasked with performing the following calculations on the Lennard-Jones potential:

1 – What is the separation where the potential energy is zero?

2 – What is the force at this separation?

3 – What is the equilibrium separation ?

4 – What is the well depth at ?

5 – Evaluate for where

For x equal to 2, 2.5, and 3σ, this integral is equal to -0.024822, -0.0081767, and -0.0032901 respectively. Compared to the entire integral for 1 to infinity these values are equivalent to 5.69, 1.87, and 0.75% respectively. These values demonstrate that not including pair interactions further away than 3σ still ensures that the overwhelming majority of significant interactions would still be included.

Periodic Boundary Conditions

1 mL of water weighs approximately 1 g. The number of moles present in 1 g of water is 1/18.01528. The number of water molecules present in 1/18.01528 moles is NA/18.01528 = 3.3427961x1022 molecules. Therefore 10000 molecules of water only fills a volume of 10000/(3.3427961x1022) mL, approximately 3x10-19 mL.

Consider an atom at the centre of a simulation box from (0,0,0) to (1,1,1), which moves along the vector (0.7,0.6,0.2) in a single time-step. We can determine this simply by traveling along each axis individually. First, we travel from x=0.5 to x=1.2, which is x=0.2 after moving through the periodic boundary. Along the y-axis we travel from y=0.5 to y=1.1, which is y=0.1 after moving through the periodic boundary. Lastly along the z-axis we travel from z=0.5 to z=0.7. Overall this amounts to traveling from (0.5,0.5,0.5) to (0.2,0.1,0.7).

Reduced Units

Commonly in simulation work we shift to a different set of units so as to make data handling more facile. Here LAMMPS works in the Lennard-Jones reduced units. We have been asked to convert the following from reduced units for the case of Argon:

1 – The distance

The reduced distance , therefore . Here

2 – What is the well depth in kJ mol-1?

The well depth was previously shown to be 1ε, which is defined by

3 – What is the reduced temperature in real units?

The reduced temperature is defined by

Creating the Simulation Box

When creating the system to simulate we must first populate our space with particles. In the work in the above report LAMMPS does this by placing the particles onto an ordered crystal lattice. One's first thought may be to instead just randomly distribute the particles, but this can lead to particles being initially placed far too close together. If two particles were placed less that 1σ apart, then there would be a corresponding incredibly high repulsive force. In a system with these unrealistic cases the energy density will be far higher than in a real system. As such it is just easier to initially start with ordered positions, and introduce disorder in a different fashion — in the simulations in this work, this was achieved by giving random velocities that still fit a Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution.

In some of our first calculations we generated a simple cubic system with a number density of 0.8. As such the shortest distance between particles (and the side-length of a unit cell) was 1.07722 (reduced units). We are asked to determine the side-length of a face-centered cubic lattice cell which would give rise to a number density of 1.2. We remember that the face-centered cubic cell contains 4 lattice points, compared to the simple cubic's 1. As such the face-centered cell which gives a number density of 1.2 has the same volume as the simple cubic cell which give a number density of 0.3 (1.2/4). Number density is equal to the number of lattice points per unit cell divided by the volume of the unit cell: , rearranging this we find that the 1.2 number density face-centered cubic unit cell has a side-length of 1.49380 (reduced units).

Example code provided to us generates a 1000 unit cell box of a simple cubic lattice. It therefore contains 1000 lattice points, as the simple cubic lattice contains only a single lattice point. If we had instead generated a face-centered cubic lattice, it would contain four times as many lattice points mdash; 4000 points, and therefore 4000 atoms.

Setting the Properties of Atoms

We were asked with explaining the following code using the LAMMPS manual:

- mass 1 1.0

- pair_style lj/cut 3.0

- pair_coeff * * 1.0 1.0

Line 1 set the mass of atom type 1 to the value of 1.0. We only simulate a single type of atom in our calculations, so atom type 1 refers to all of the atoms seen in our system. We note that the mass is in reduced units, and so for the argon system corresponds to 6.69x10-26 kg. Line 2 refers to the model or set of formulae used to calculate pairwise interactions between atoms. Here, the parameter lj/cut means that we are using the Lennard-Jones potential, with no Coulombic calculation, and cuts-off after a certain distance. The second parameter 3.0 tells LAMMPS what that cut-off threshold is — 3σ. As previous tasks demonstrated, this still preserves the overwhelming majority of interactions. Line 3 sets the force field coefficients for pairwise interactions. The first two * mean that it is referring to the pairwise interactions of any pair of atom types (as we only have the single atom type, 1, this could have equally been 1 1) The third and fourth parameters, 1.0 1.0, set the force field coefficients to 1. For the molecular dynamics of more complex particles, e.g. organic molecules, a more complex force field is required to account for molecular geometries and degrees of freedom. In the case of our simulations, our particles are modeled as uniform points, and therefore have no need for a more complex force field model.

We note that the provided code requires the setting of both initial position and velocity. This demonstrates that LAMMPS utilises the Velocity–Verlet algorithm to perform its dynamics.

Running the Simulation

We are asked to discuss the usage of a variable timestep in the following code, and why not just get rid of the first two lines and hard-code the values into the last two lines:

- variable timestep equal 0.001

- variable n_steps equal floor(100/${timestep})

- timestep ${timestep}

- ...

- run ${n_steps}

Firstly the usage of variables provides a single location where a value can be changed, a change which will automatically propagate to all other points where the variable is used. One may wish to study the effect of changing timestep on the simulation, and therefore being able to change its value quickly is important — changing it manually would be much more involved. We can also use the variable timestep to automatically work out the number of steps needed to simulate a certain amount of time. The second line of code above calculates the number of steps needed to simulate 100 time units for any general value of timestep. Again, here it would require a more involved process (likely easily fraught with human error) to require the user to work out and change the value of n_steps each time they wished to change the value of timestep. Both of these variables are of note to the person running the simulation, and therefore having them easily available as parameters is of benefit.

Checking Equilibration

Discussed in main body

Temperature and Pressure Control

Discussed in main body

Thermostats and Barostats

In order to manage the total energy of our system (the importance of which has been previously discussed) we must look at the kinetic energy of our system. From the equipartion theorem we know that the total kinetic energy is related to the temperature of our system by the following:

As the temperature fluctuates (partly due to errors in the prediction of velocities under the Velocity–Verlet algorithm) we need to tweak the velocities to keep the instantaneous temperature () the same as the desired temperature (). We do this by modifying the velocities by some uniform scaling factor γ. The below calculations derive the value of γ.

At some time we have a system of particles with velocities and temperature . We wish the system to instead have the temperature , which would be the case if the particles instead had velocities .

We define a scaling variable such that:

Therefore:

Rearranging to:

Examining the Input Script

We are asked to analyse and explain the following line of code from npt.in:

- fix aves all ave/time 100 1000 100000 v_dens v_temp v_press v_dens2 v_temp2 v_press2

This code generates an average of the six stated variables using a specified set of data. The three numbers in the code, 100, 1000, 100000, define this set of data to be used to form a time-based average. The final number states the final data-point to be used in the average. The second number states how many data points will be used to generate the average. The first number states the distance between used data points. Therefore the above code dictates that every 100th data point up to point 100000 (a total of 1000 points) will be used to find the average.

We also note the line run 100000 which means that the system will simulate 100000 steps. From the above definition therefore only a single average will be outputted for each variable, as the system will only simulate enough steps to complete a single average. For a time-step of 0.001 this will simulate 100 reduced time units (approximately 2x10-10 seconds for the argon system).

Plotting the Equation of State

Discussed in main body

Heat Capacity Calculation

Discussed in main body

The Radial Distribution Function

Discussed in main body

Mean Squared Displacement

Discussed in main body