User:Ts4111

Inorganic Computational Lab

EX3 Section

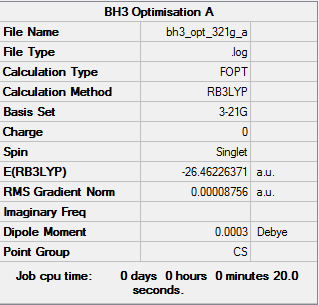

BH3 Optimisation (3-21G)

Optimisation log file: here

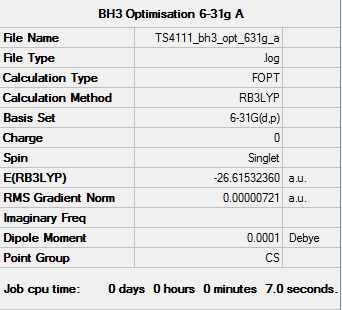

BH3 Optimisation (6-21G)

Optimisation log file: here

| Summary data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000012 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000008 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000064 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000039 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.128214D-09

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

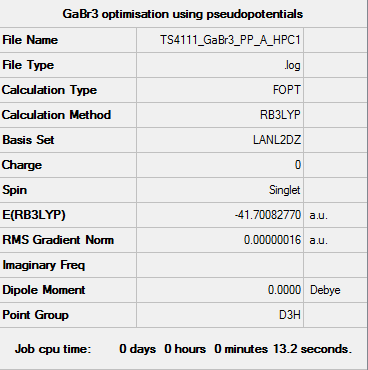

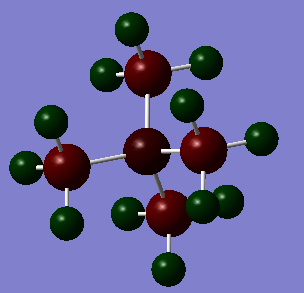

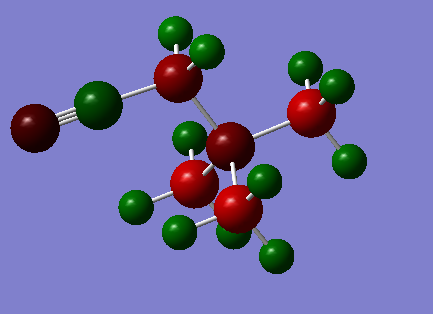

GaBr3 Optimisation using pseudopotentials

Optimisation File: DOI:10042/92765

| Summary data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000000 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000000 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000003 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000002 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.307736D-12

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

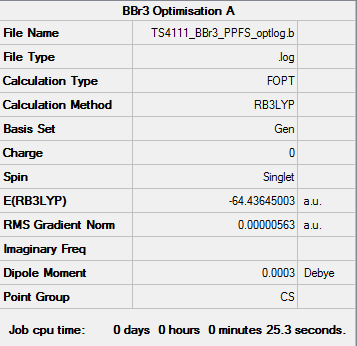

BBr3 Optimisation using 6-31G basis set and pseudopotentials

Optimisation File: DOI:10042/85893

| Summary data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000012 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000007 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000048 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000031 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-7.160231D-10

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

Geometry Data

| BH3 | BBr3 | GaBr3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| r(E-X) (Angstroms) | 1.19 | 1.93 | 2.35 |

| θ(X-E-X) (degrees) | 120.0 | 120.0 | 120.0 |

Pauling electronegativities: B: 2.04, H: 2.20, Br: 2.96, Ga: 1.81.

When changing the ligand from H to Br, the bond length increases by 0.74 Angstroms. Br is much larger than H and so its valence orbitals are far more diffuse, and this will increase bond length. Electron repulsions between Br atoms is also likely to slightly increase the bond length. In addition, H is closer to B in terms of electronegativity, and so the AO interaction will be stronger, and a greater stabilisation energy will be realised. As a result the bond will be stronger, and as a general rule this will decrease the length of the bond. Boron is also closer in size to H and this increases orbital overlap and thus bond strength as well.

Bond length increases once more if the central atom is changed to Ga. The electronegativity disparity between Ga and Br is even greater than that between B and Br, and as described above this will lower the stablisation energy achieved through MO formation and subsequently weaken the bond, making it even longer. Ga is also larger than B and the increased diffuseness of valence orbitals will decrease electron overlap and keep the atoms further apart.

As atoms become larger the effective nuclear charge decreases and so the nucleus - electron attraction energy will decrease, weakening the bond, and this is observed in both instances above.

A chemical bond could be described as an interaction between two atoms which lowers the total energy of the system. As the distance between two atoms or groups decreases, electrostatic interactions will also increase. Nucleus - electron interactions will lower the energy of the system and electron - electron and nucleus - nucleus interactions will increase the energy. If a bond is formed, then the two species will be at a distance apart that affords maximum stability, due to the nucleus - electron attractive forces outweighing the repulsive forces. The total energy of the system will increase if the bond lengthens because attractive forces will decrease in magnitude faster than repulsive forces, and the converse is true for bond shortening. From a molecular orbital perspective, a bond can be thought of as a favourable interaction between atomic or fragment orbitals which creates new bonding and anti-bonding molecular orbitals, where the magnitude of the energy change from electrons moving to bonding orbitals is greater than the magnitude of the energy change from electrons moving into anti-bonding orbitals. Bonds are points of constructive interference between electron wavefunctions.

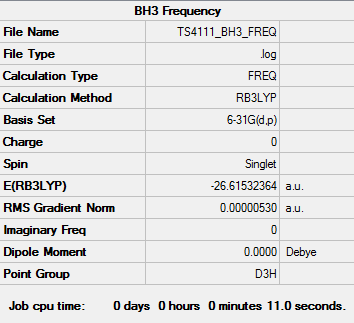

BH3 Frequency Analysis

Frequency log file: here

| Summary data | Low Frequencies | |

|---|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -14.5183 -14.5142 -10.8197 0.0008 0.0169 0.3454 Low frequencies --- 1162.9508 1213.1230 1213.1232 |

It is important to carry out frequency analysis, in order to ensure that the stationary point found in the optimisation calculations was a minima, and therefore an energetically stable point rather than a saddle point, for instance. The same basis set and method must be used for frequency analysis as for optimisation, as otherwise different energies are calculated and the two calculations will not be relative to each other. The low frequencies obtained, and shown (as above), correspond to rotational and translational modes. Ideally they should be equal to zero, however the calculations used are not extensive enough to ensure this. [1] This is why it is important to ensure that the low frequencies all lie within a narrow range of wavenumbers.

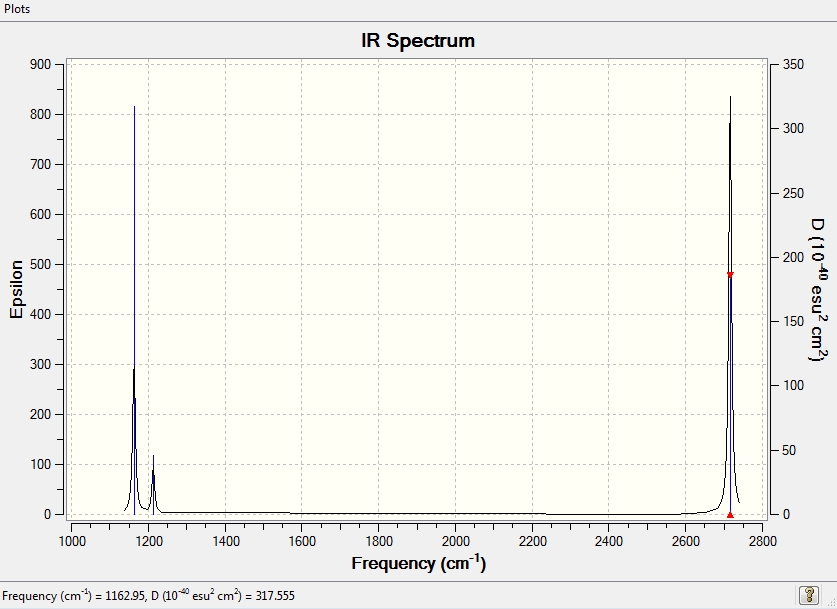

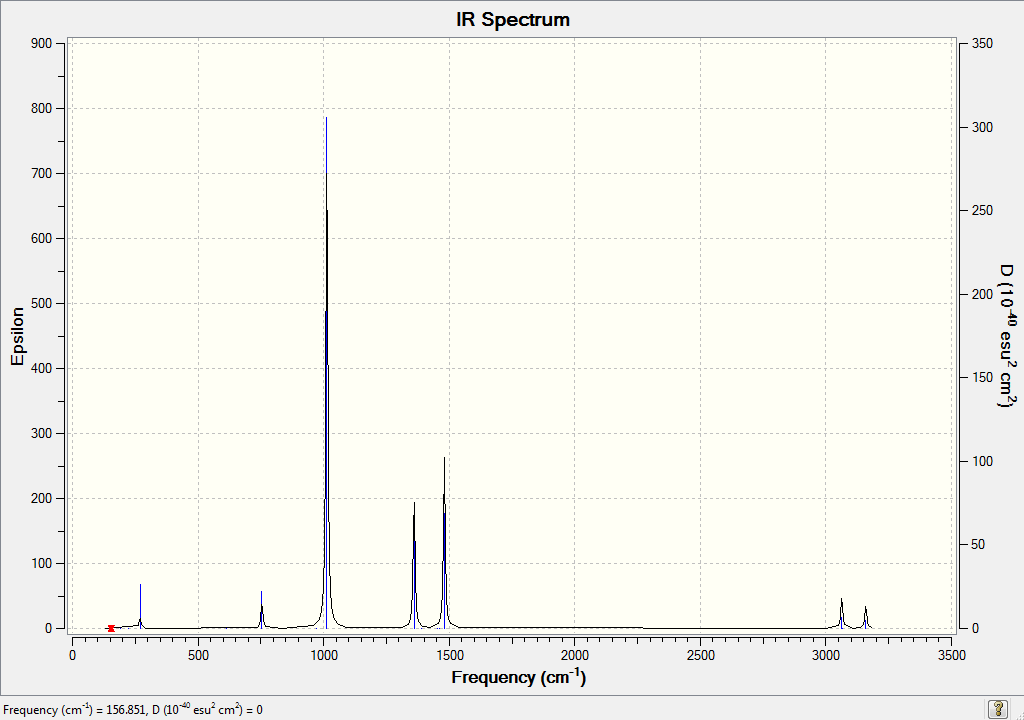

Vibrational Spectrum for BH3

6 vibrational modes were calculated, and this is consistent with the 3N - 6 rule.

| Wavenumber | Intensity | IR Active? | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1162.95 | 92.5706 | yes | bend |

| 1213.12 | 14.0539 | very slightly | bend |

| 1213.12 | 14.0533 | very slightly | bend |

| 2582.66 | 0.000 | no | stretch |

| 2715.81 | 126.3291 | yes | stretch |

| 2715.81 | 126.3231 | yes | stretch |

The molecule clearly has 6 vibrational modes. However, one mode has an intensity of 0 and this is because it disobeys vibrational selection rules. The two peaks at 1213 and 2716 wavenumbers overlap with each other, giving the appearance of one peak. This is why 3 peaks appear on the spectrum instead of 6.

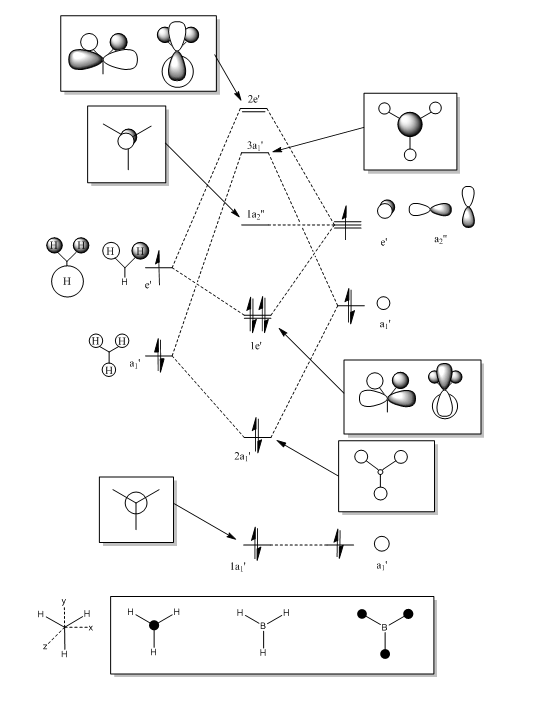

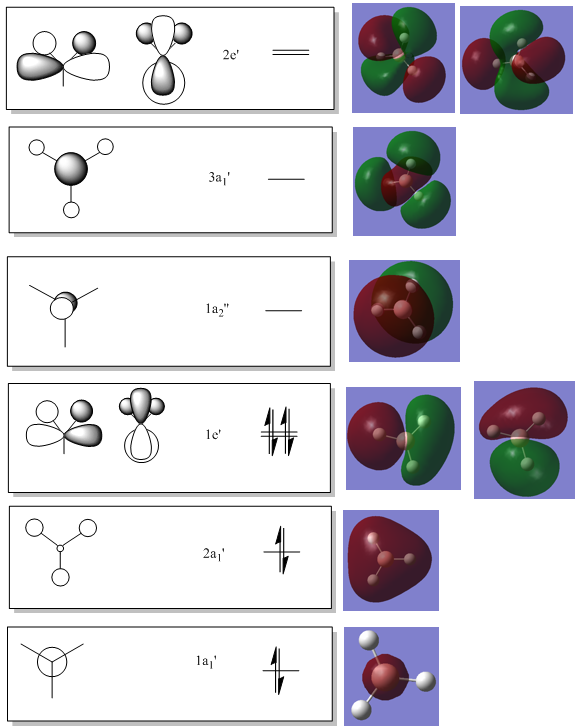

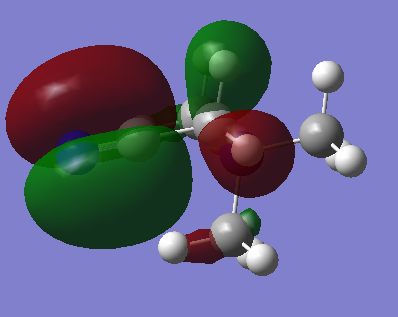

BH3 MO Analysis

The first MO is a core orbital and this is confirmed by the calculated MO surface which shows clearly that the MO only extends over the boron atom. This orbital is far too low in energy to interact with other orbitals. The energy difference would be far too great. Only AOs of similar energy can interact.

The second MO is more delocalised than the LCAO suggests, but correlates in that it is fully bonding. The two degenerate 1e’ MOs are slightly less symmetrical than the LCAOs, and this is probably due to inaccuracies in the computed calculations. They do look very similar though.

The 1a2’’ calculated MO surface looks almost identical to the LCAO, although it does seem to extend out in a way that appears larger than a standard p orbital. It is obviously a result of the boron pz orbital though.

The 3a1’ orbital looks very similar to the LCAO, although it is a little less symmetrical, again probably due to calculation shortcomings. The MO clearly shows the three nodal planes like the LCAO.

The degenerate 2e’ orbitals strongly resemble the suggested LCAOs, and the s orbitals of two hydrogen atoms interacting out-of-phase with the p orbitals of the boron atom can clearly be seen in both. These close out-of-phase interactions make them strongly anti-bonding orbitals.

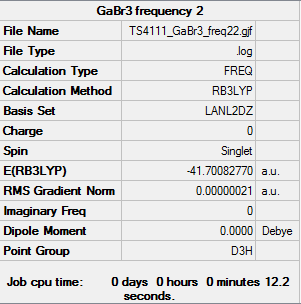

GaBr3 Frequency Analysis

Frequency log file: here

| Summary data | Low Frequencies | |

|---|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -1.4877 -0.0015 -0.0002 0.0096 0.6540 0.6540 Low frequencies --- 76.3920 76.3924 99.6767 |

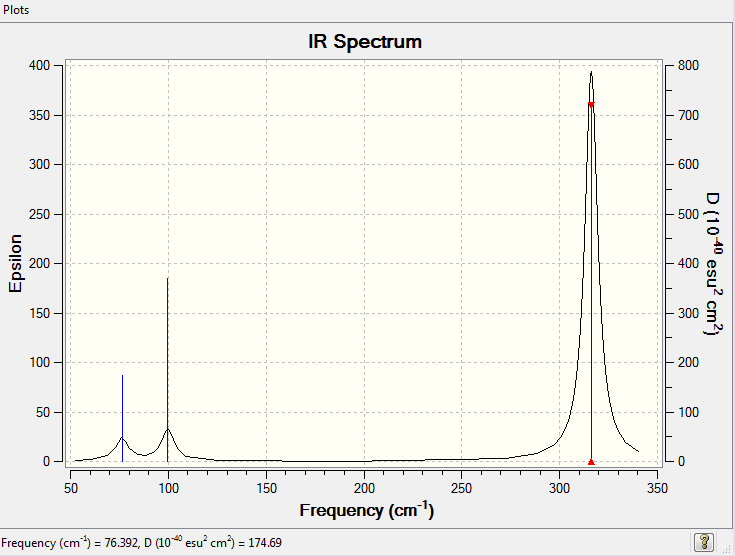

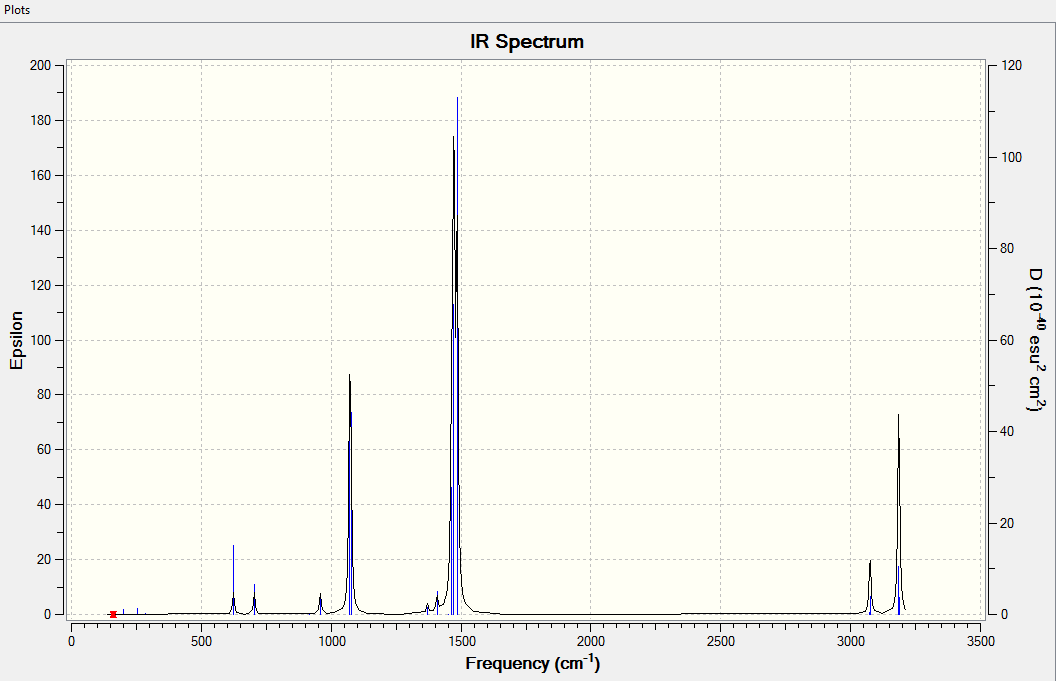

Vibrational Spectrum for GaBr3

| Wavenumber | Intensity | IR Active? | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 76.39 | 3.3451 | very slightly | bend |

| 76.39 | 3.3450 | very slightly | bend |

| 99.68 | 9.2166 | very slightly | bend |

| 197.33 | 0.000 | no | stretch |

| 316.18 | 57.0655 | yes | bend |

| 316.8 | 57.0669 | yes | bend |

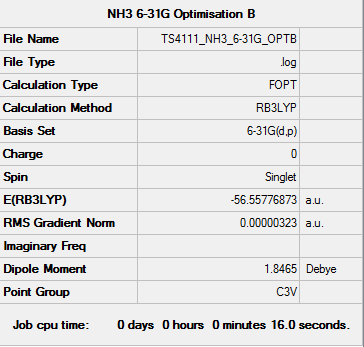

NH3 Optimisation (6-21G)

Optimisation log file: here

| Summary data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000006 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000004 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000012 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000008 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-9.844308D-11

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

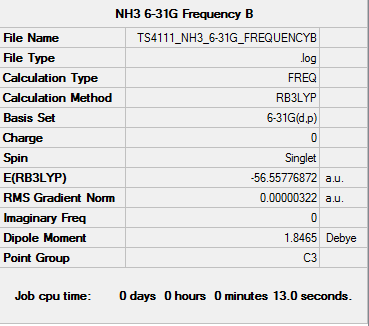

NH3 Frequency Analysis

Frequency log file: here

| Summary data | Low Frequencies | |

|---|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -0.0138 -0.0026 0.0022 7.0783 8.0932 8.0937 Low frequencies --- 1089.3840 1693.9368 1693.9368 |

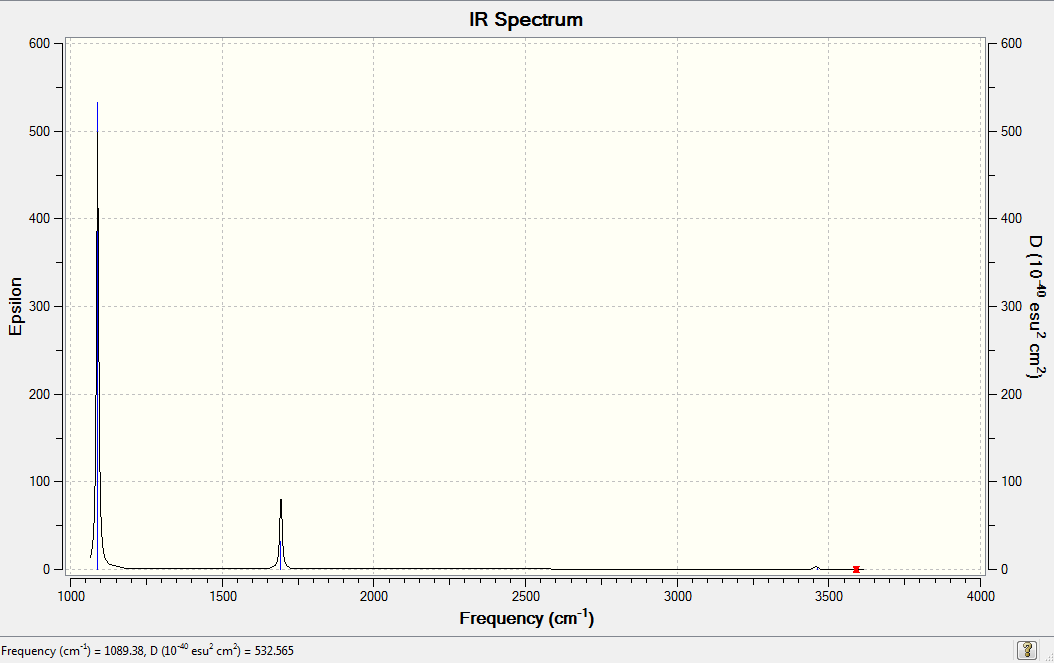

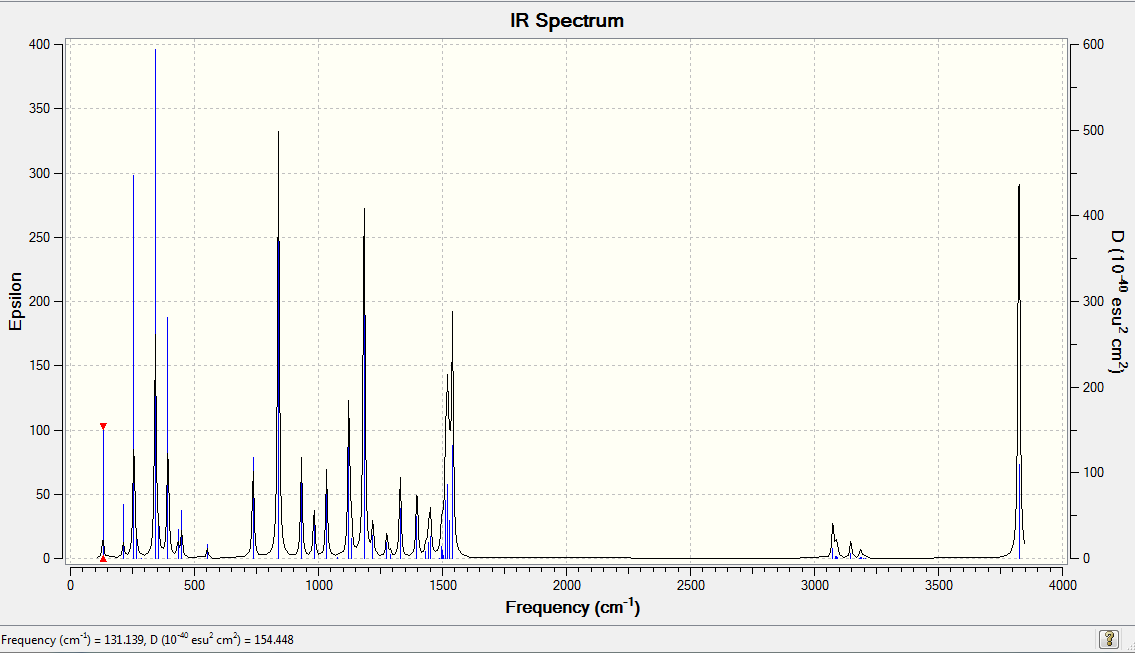

Vibrational Spectrum for NH3

| Wavenumber | Intensity | IR Active? | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1089.38 | 145.4273 | yes | bend |

| 1693.94 | 13.5570 | very slightly | bend |

| 1693.94 | 13.5571 | very slightly | bend |

| 3461.30 | 1.0595 | very slightly | stretch |

| 3589.86 | 0.2699 | no | bendy stretch |

| 3589.86 | 0.2699 | no | bendy stretch |

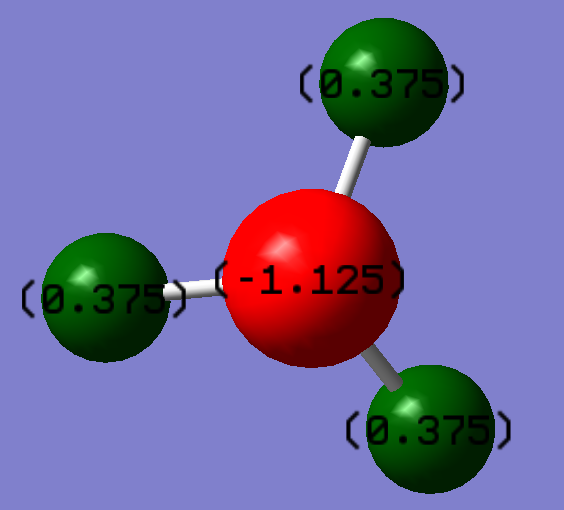

NBO Analysis of NH3

As can be seen on the image below, there is a higher electron density on the nitrogen compared to the hydrogen atoms. This is to be expected since nitrogen has a Pauling electronegativity of 3.04 and hydrogen has a Pauling electronegativity of 2.20. The molecule will therefore be in a more stable configuration when electron density is greater around the nitrogen.

Dspace file: DOI:10042/109691

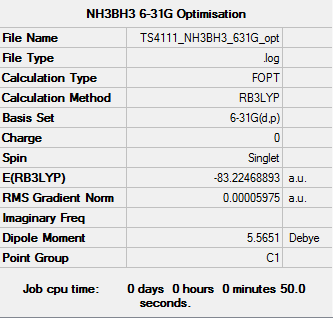

NH3BH3 Optimisation (6-31G)

Optimisation log file: here

| Summary data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000122 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000058 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000513 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000296 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.631175D-07

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

NH3BH3 Frequency Analysis

Frequency log file: here

| Summary data | Low Frequencies | |

|---|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -0.0014 -0.0006 -0.0003 17.1660 17.5746 37.3520 Low frequencies --- 265.9185 632.2125 639.3528 |

NH3BH3 Energy

BH3 Energy: 26.61532360 AU

NH3 Energy: 56.55776856 AU

BH3NH3 Energy: 83.22468893 AU

ΔE = E(BH3NH3) - [E(BH3) + E(NH3)]

ΔE = 0.05 AU

ΔE = 135 kJ mol-1

This represents quite a weak bond. A single carbon carbon bond is roughly 350 kJ mol-1, so ethane is a much stronger molecule. Two isoenergetic fragments combining together will give a large stabilisation energy, but BH3 fragment orbitals have a higher energy than NH3 fragment orbitals, so that the FO combination has a smaller stabilisation energy compared to ethane, giving a weaker bond.

Project Section

Liquids are able to exist at room temperature because of relatively weak intermolecular interactions, such as van der Waals forces and hydrogen bonds. The concept of a room temperature ionic liquid then, does seem somewhat counter-intuitive, as ionic forces are generally much stronger than intermolecular forces in liquids. LiF has a melting point of ~ 848 °C, [2] NaCl has a melting point of ~ 801°C,[3] and KBr has a melting point of ~ 734 °C. [4] These temperatures are all very high, although as charge density decreases from LiF to KBr, the melting points of the salts decreases. Obviously, an array of factors influences the melting point, but increasing diffuseness of charge certainly seems to correlate with a decrease in melting point, and this can be rationalised within the context of weaker intermolecular interactions; requiring less thermal energy to be overcome. When ‘designing’ ionic liquids, this is a factor that needs to be taken into account. Molecules such as the tetramethyl ammonium cation are much larger and bulkier than the single nucleus ions mentioned above, but still carry the same charge magnitude. The charge carried on larger molecules such as this isn’t uniformly spread over the molecule, but nonetheless it does grant a higher level of charge delocalisation.

Given more time, the properties of carborane ions and borane hydride clusters could have been investigated, which could presumably be useful in ionic liquids due to their very low surface charge. Perhaps different groups would need to be added to the side of these materials to lower the symmetry though. Nevertheless, it would be really interesting to examine whether this class of compounds could interact with other ions in a liquid, or perhaps dissolve in ionic liquids to slightly change the properties. These kind of considerations are way outside the remit of this project though.

In this project I will be investigating some of the properties of molecular cations.

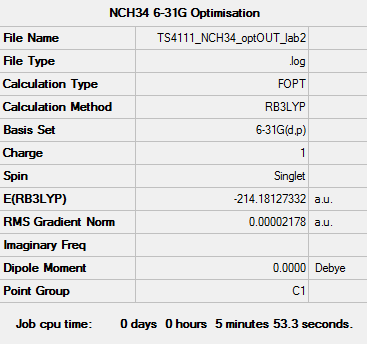

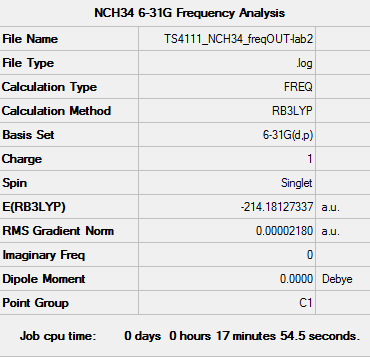

[N(CH4)4]+ Optimisation (6-31G)

Optimisation log file: here

Dspace: DOI:10042/110231

| Summary data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000071 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000017 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.001641 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000335 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-5.853336D-08

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

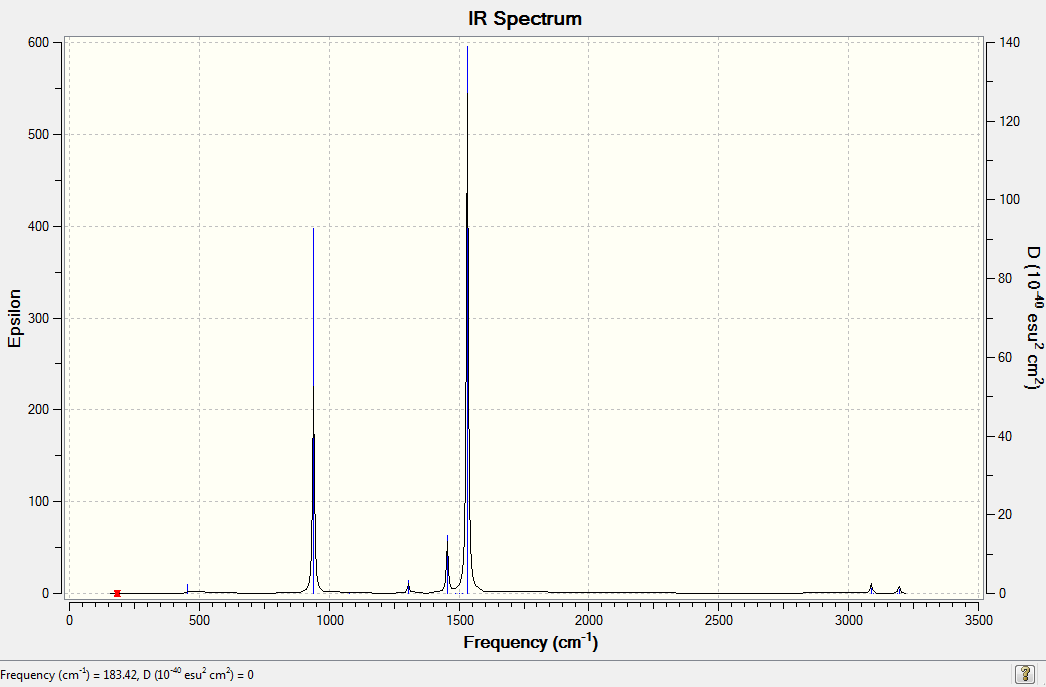

[N(CH4)4]+ Frequency Analysis

Frequency log file: here

| Summary data | Low Frequencies | |

|---|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -1.0040 -0.0011 -0.0010 -0.0007 7.4669 10.1348 Low frequencies --- 183.4201 288.8972 289.3778 |

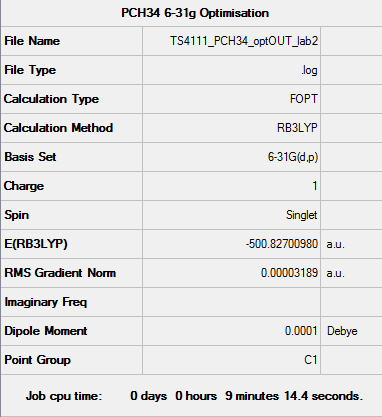

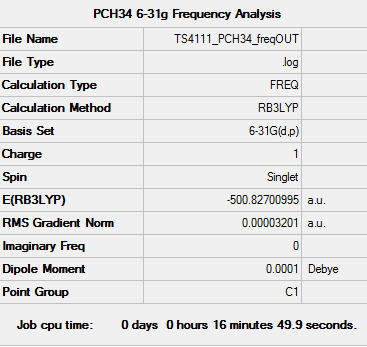

[P(CH4)4]+ Optimisation (6-31G)

Dspace: DOI:10042/110216

Optimisation file: here

| Summary data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000156 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000033 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000612 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000247 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.766382D-07

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

[P(CH4)4]+ Frequency Analysis

Frequency log file: here

| Summary data | Low Frequencies | |

|---|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -0.0016 0.0016 0.0030 5.3356 7.4708 9.8861 Low frequencies --- 156.8542 192.2092 192.4733 |

[S(CH3)3]+ Optimisation (6-31G)

Optimisation log file: here

Dspace: DOI:10042/110199

| Summary data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000037 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000012 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000751 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000201 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-2.209331D-08

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

[S(CH3)3]+ Frequency Analysis

Frequency log file: here

| Summary data | Low Frequencies | |

|---|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -9.2505 -4.8914 0.0016 0.0022 0.0042 8.8812 Low frequencies --- 161.3614 198.8832 199.6934 |

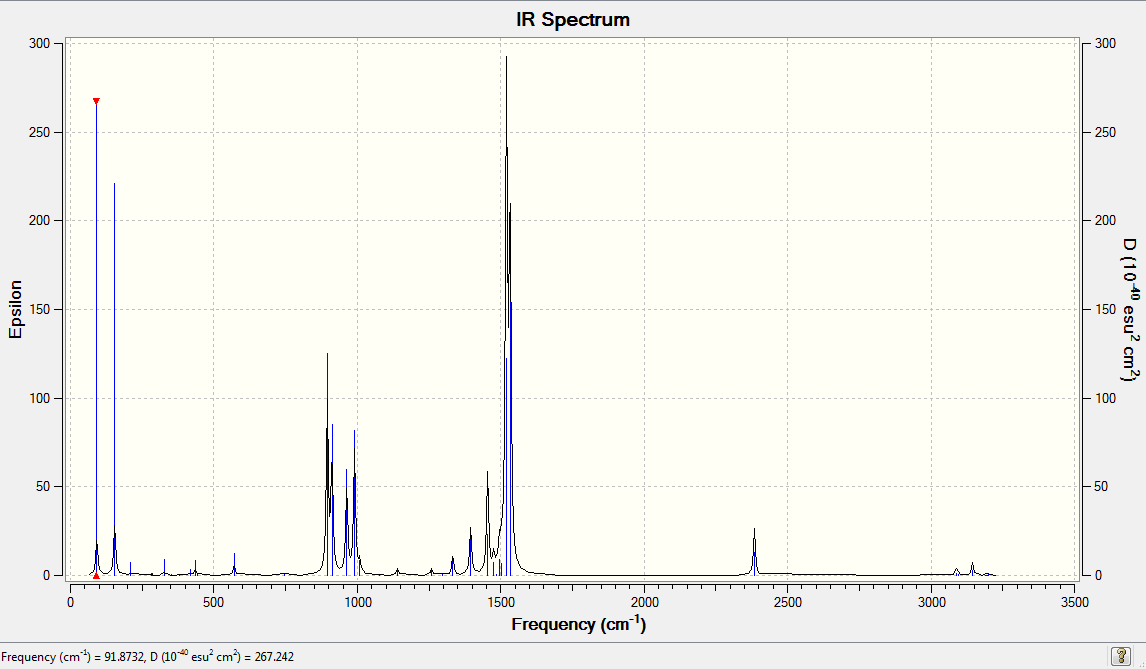

All vibrational analyses yielded a number of vibrational modes equal to (3N - 6), where N is the number of atoms in the molecule, supporting the validity of the results.

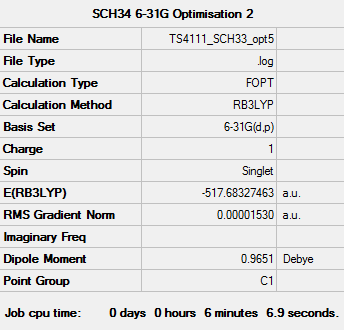

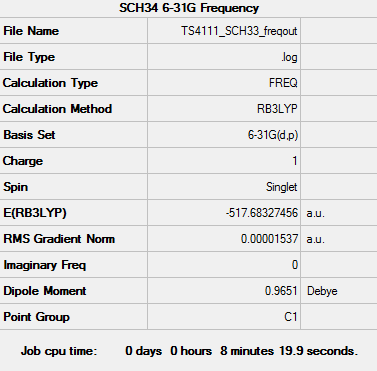

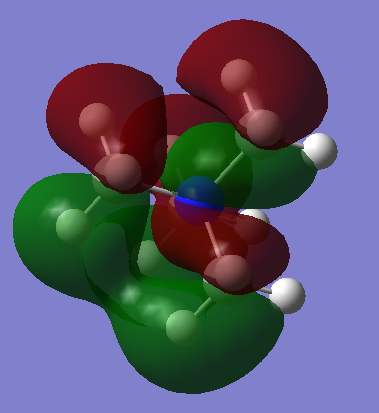

[N(CH3)4]+ MO Analysis

| Pauling Electronegativity | |

|---|---|

| MO 24: There are four nodal planes in this MO, although the out-of-phase interaction surface area is much higher than the other MOs pictured. The two nodal planes closer to the centre of the molecule deviate heavily from being flat though, so that these planes could almost be described as 3D anti-bonding surfaces. The nitrogen AO appears to contribute in the opposite phase to several hydrogen atom AOs close to it, decreasing the stability of the MO. Significant anti-bonding interaction takes place on every methyl group, and all sections next to the nitrogen-centred section are out of phase with it. Strongly bonding interactions take place within each ‘level’ of the MO, and weak bonding interactions take place between non-adjacent levels of the same phase. Overall, I would imagine that this was a non-bonding, or weakly bonding orbital. The orbital has several rather delocalised sections extending away from the nuclei. A mirror plane runs through the centre of this MO, and this plane can be repeated in two other positions on the molecule, meaning that this orbital has two degenerate MOs. |

|

| MO 16: The nodal plane present in MO 7 is again featured in this MO, and in this orbital it is also possible in a number of different, symmetrically equivalent orientations, so that there are degenerate orbitals for this MO as well. There are 5 nodal planes in this MO, and the extent of anti-bonding interactions is far greater compared to MO 10. Out-of-phase interactions take place within every methyl group, and this raises the energy of the molecule. |

|

| MO 10: This orbital contains four nodal planes. Strong bonding interactions take place between the carbon AOs and the AOs of the hydrogens directly bonded to them. Through-space bonding interactions between the methyl groups will also increase the bonding character of this MO. The nitrogen AO contributes out of phase to the methyl group fragment orbitals, and with four points of close contact between oppositely charged components, the energy is raised. It must be noted though, that the surface area of oppositely-charged interaction is the factor that is actually proportional to the bonding character of an MO, and the surface area at each nodal plane is relatively small. The close range bonding interactions of AOs on the methyl group fragment orbitals outweigh the anti-bonding interactions. The MO is localised on the nitrogen and methyl groups. This MO is not degenerate. |

|

| MO 7:This orbital shows a clear nodal plane through the middle, and is of a higher (less negative) energy compared to the first MO shown. Most interactions a strongly bonding, as atoms from two of the methyl groups interact in-phase with each other. Through-space anti-bonding will take place between the two ‘halves’ of the orbital, raising the energy of this MO. The two ‘halves’ are not actually symmetrical though, and this is probably due to the inaccuracies of the calculations. The nitrogen AOs do not appear to significantly contribute to this orbital, and the two methyl groups ‘in the middle’ seem to contribute a lot less as well. A mirror plane exists in the same position as the nodal plane, and this mirror plane has 3 equivalents, giving 3 degenerate MOs. The electron density is quite localised over two of the methyl groups. |

|

| MO 6: This is a relatively simple orbital with no nodes. The MO is strongly bonding, as all atomic contributions are in phase. The orbital is delocalised over all but the peripheral edges of the molecule. This is a non-core orbital because atomic orbitals interact with each other. All MOs lower in energy are core orbitals, because they are simply comprised of non-interacting atomic orbitals. |

|

Charge Distribution Analysis

[N(CH3)4]+ Energy Calculation log file: here

[P(CH3)4]+ Energy Calculation log file: here

[S(CH3)3]+ Energy Calculation log file: here

| [N(CH3)4]+ | [P(CH3)4]+ | [S(CH3)3]+ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heteroatom | - 0.295 | 1.667 | 0.917 |

| Carbon | - 0.483 | - 1.060 | - 0.846 |

| Hydrogen | 0.269 | 0.298 | 0.279 - 0.297 |

| Pauling Electronegativity | |

|---|---|

| Nitrogen | 3.04 |

| Phosphorous | 2.19 |

| Sulphur | 2.58 |

| Carbon | 2.55 |

| Hydrogen | 2.20 |

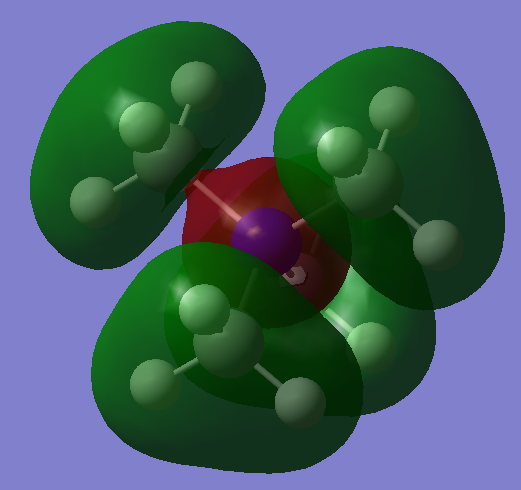

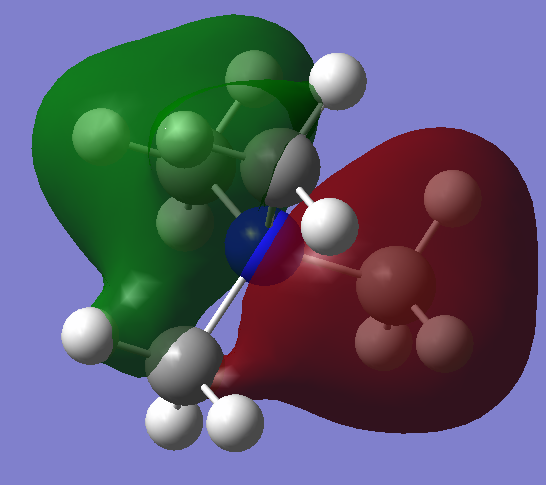

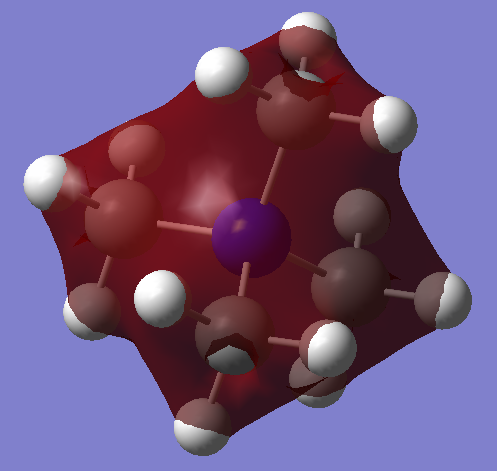

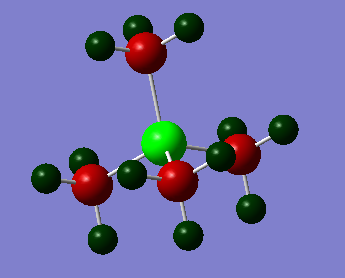

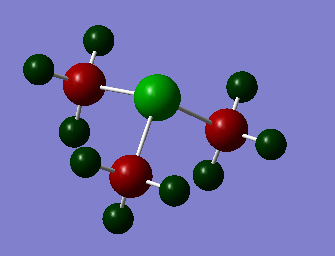

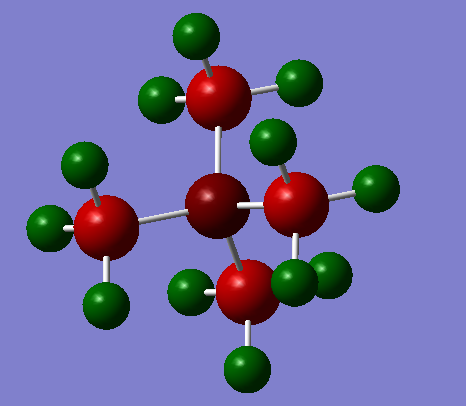

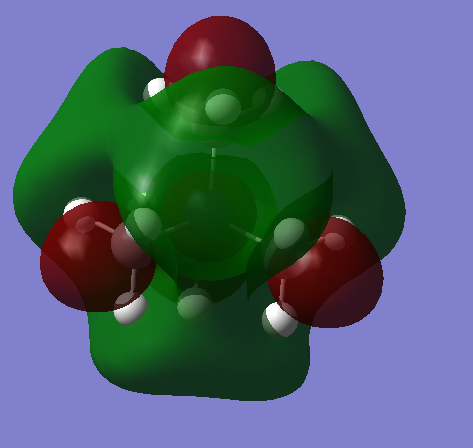

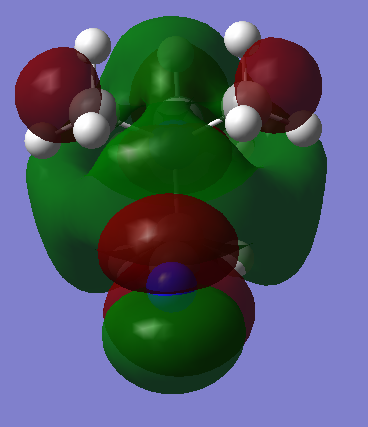

In the images below, red represents negative charge, and green represents positive charge. All representations are shown with very light green indicated a charge of 1.7 and very light red indicating a charge of - 1.7. Charges of lower magnitude appear darker.

| [N(CH3)4]+ | [P(CH3)4]+ | [S(CH3)3]+ |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

On the [N(CH3)4]+ molecule, it can be seen that both the carbon and nitrogen atoms are negatively charged, because they are both more electronegative than the hydrogen atoms. An uneven positive charge extends over the surface of the molecule. However, the carbon atoms are more negatively charged than the nitrogen atom, despite the fact that nitrogen is the most electronegative atom in the molecule. It is surprising that the charge distribution on this molecule does not extend in a roughly spherical manner from the centre of the molecule, since this would follow the electronegativity of the constituent atoms.

This peculiarity can be rationalised by considering the fact that the nitrogen has donated the electrons from its lone pair to form a fourth bond. This reduces the electron density around it, and perturbs the charge balance on the nitrogen atom. To explain in a different way; the nitrogen has an additional bond around it, which pulls electron density away from the nitrogen without donating any back. This is the reason that the nitrogen is less negatively charged, despite being more electronegative. In the other two molecules the heteroatom, again, is the donating atom, and thus experiences an increased positive charge.

In traditional descriptions of tetraalkylammonium ions a formal positive charge is placed on the nitrogen atom. In reality, the carbon atoms are more electronegative, but when modelling the positive charge as a point, the symmetrical centre of the charge is on the nitrogen atom. The formal positive charge on the nitrogen in traditional descriptions indicates the fact that it is the nitrogen that has lost an electron to form a bond. The phosphorous atom in [P(CH3)4]+ is more electropositive than carbon, and this partly explains its very high charge. Each carbon on the molecule is negatively charged; more so than on any other molecule.

In all three molecules, the negative charge, and therefore electron density, is strongest at the carbon atoms. Positive charge is also spread around the outside of the molecule, making the hydrogen atoms positively charged. This result is supported by literature. [5] Carbon is more electronegative than hydrogen, and on each molecule the carbon atoms are attached to three hydrogens. This means that the carbon will be withdrawing electron density from three bonds, increasing the negative charge on it. This is another factor contributing to phenomenon of favoured electron density at the carbons over the heteroatom. Each carbon also receives a quarter of the donated electron density from the heteroatom.

The charge of the central heteroatom becomes more positive as electronegativity decreases. The contribution AOs make to a MO, and thus to bonds, is closely related to how close in energy the AOs are to the associated MO energy. The MOs that strengthen the bonding interactions will be low in energy, and therefore more electronegative elements will be closer in energy to the bonding MOs. This means that the bonding MOs will contain more character from the more electronegative AOs. Although this in itself doesn’t affect the electron contribution from an atom, it will mean that electron density around an atom will increase with electronegativity, as the bonding MOs will be centred on the atom more.

[P(CH3)4]+ exhibits the greatest charge disparity, and despite having the most positively charged heteroatom, it also has the most highly charged hydrogen atoms. This will increase the charge density on the surface. [N(CH3)4]+ has the lowest charge hydrogens, however, the C-X bond lengths are also decreased in this molecule, decreasing the molecular radius. It is therefore hypothesised that these two ions would have similar surface charges and thus have similar properties when used in ionic liquids (e.g. melting point). [S(CH3)3]+ seems to have slightly larger C-X bond lengths than [P(CH3)4]+, and also a slightly lower charge on the hydrogens. However, it only has three methyl groups, and the positively charged sulphur atom is more exposed. It is expected that this molecule has a slightly higher surface charge compared to the other two molecules as a result, and would therefore form liquids with higher melting points.

As positive charge increases on the heteroatom, the contribution this atom makes to the C-X bond decreases, and this is expected as the atom will therefore have less electron density to donate.

C-X Bond Contribution Analysis

| Heteroatom | X Contribution (%) | C Contribution (%) | Bond Length (A) |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 66 | 34 | 1.510 |

| P | 35 | 65 | 1.817 |

| S | 51 | 49 | 1.823 |

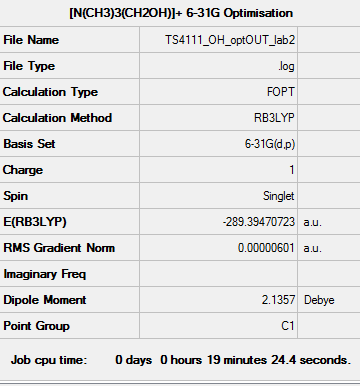

[N(CH3)3(CH2OH)]+ Optimisation (6-31G)

Optimisation log file: here

Dspace: DOI:10042/110254

| Summary data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000012 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000003 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000624 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000137 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-5.059183D-09

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

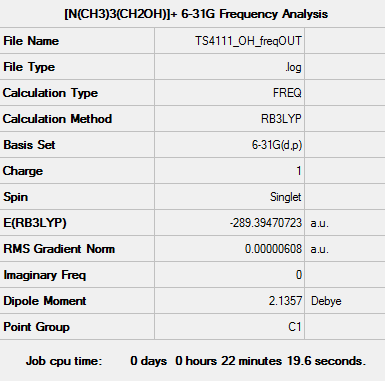

[N(CH3)3(CH2OH)]+ Frequency Analysis

Frequency log file: here

| Summary data | Low Frequencies | |

|---|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -8.3771 -5.0368 0.0004 0.0005 0.0010 1.5956 Low frequencies --- 131.1393 213.6007 255.7615 |

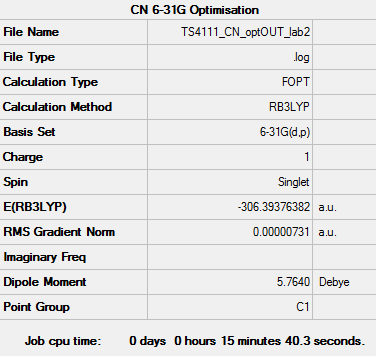

[N(CH3)3(CH2CN)]+ Optimisation (6-31G)

Optimisation log file: here

Dspace: DOI:10042/110271

| Summary data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000026 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000006 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.001125 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000246 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.207778D-08

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

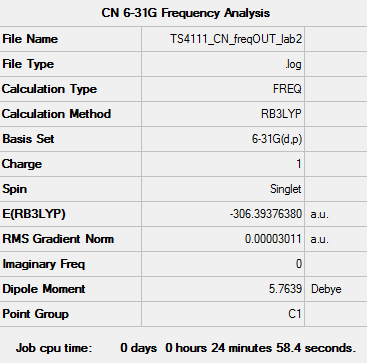

[N(CH3)3(CH2CN)]+ Frequency Analysis

Frequency log file: here

| Summary data | Low Frequencies | |

|---|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -1.6870 -0.0007 0.0003 0.0007 7.4235 9.3788 Low frequencies --- 91.8793 154.1955 210.7106 |

Charge Distribution Discussion

[N(CH3)4]+ Energy Calculation log file: here

[N(CH3)3(CH2OH)]+ Energy Calculation log file: here

[N(CH3)3(CH2CN)]+ Energy Calculation log file: here

| [N(CH3)4]+ | [N(CH3)3(CH2OH)]+ | [N(CH3)3(CH2CN)]+ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen (central) | - 0.295 | - 0.322 | - 0.289 |

| Carbon (methyl) | - 0.483 | - 0.491 - - 0.494 | -0.485 - 0.489 |

| Hydrogen (methyl) | 0.269 | 0.262 - 0.282 | 0.269 - 0.309 |

| Carbon (Hetero-group) | n/a | 0.088 | - 0.358 |

| Hydrogen (hetero-group) | n/a | 0.237, 0.249 | 0.309 |

The hydroxyl oxygen has a charge of - 0.725 and the hydroxyl hydrogen has a charge of 0.521. The cyano- carbon has a charge of 0.209 and the cyano- nitrogen has a charge of - 0.186.

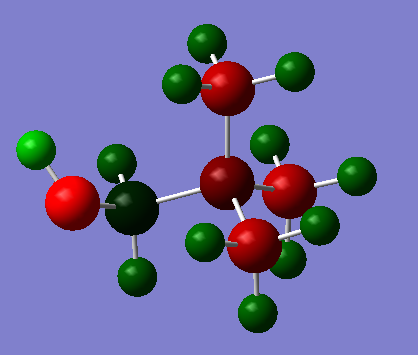

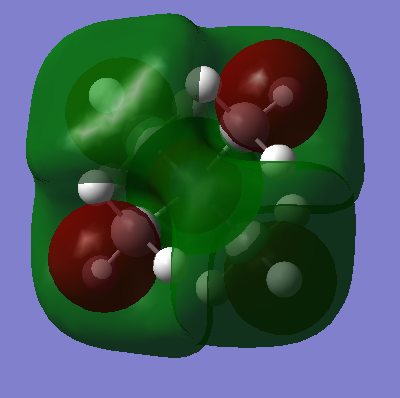

In the images below, red represents negative charge, and green represents positive charge. All representations are shown with very light green indicated a charge of 0.8 and very light red indicating a charge of - 0.8. Charges of lower magnitude appear darker.

| [N(CH3)4]+ | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

The same general trends as seen in part 1 are also seen here.

The carbon atoms connected to the OH and CN groups are obviously the most strongly affected. The electronegative oxygen withdraws electron density from the adjacent carbon, rendering it positively charged. The carbon attached to the CN group is negatively charged however.

C-N Bond Contribution Analysis

The following table details the relative contributions the hetero-group C and the central N atom make to the C-N bond. 'Species X' represents the group attached to the carbon in question.

| Species X | N Contribution (%) | C Contribution (%) | Bond Length (A) |

|---|---|---|---|

| H | 66 | 34 | 1.51 |

| OH | 67 | 33 | 1.55 |

| CN | 65 | 35 | 1.53 |

Since the partial charge on the nitrogen centre is quite similar in the three molecules, the relative contributions do not vary as much either. As in part 1; the more negative the central atom, the greater its contribution to the C-N bond. Perhaps it would be expected that the carbon atoms would contribute more to the C-N bond since they have a more negative charge and therefore more electron density over them. However, the nitrogen AOs will be closer in structure and energy to many of the most important bonding MOs, and as such a large amount of electron density will come from the nitrogen atoms. Also, much electron density from the carbon atoms will occupy space not involved with C-N bonding. Some of the negative charge on the carbon atoms is due to donation from the nitrogen anyway, and proportionally less electron density (compared to nitrogen) will go into the bonds.

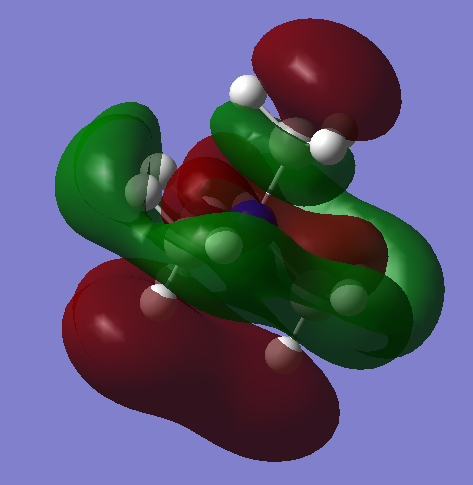

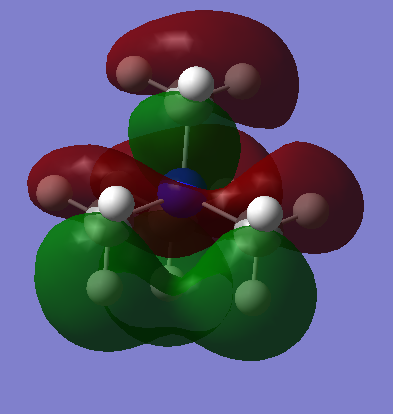

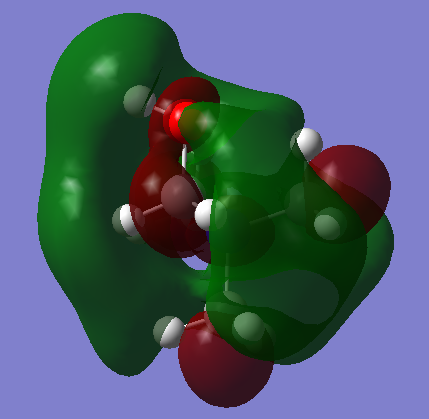

HOMO and LUMO Analysis

| HOMO Image 1 | HOMO Image 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| [N(CH3)4]+ Three bent nodal planes can be seen in this HOMO. The electrons are spread over the majority of the molecule in a delocalised way. Anti-bonding interaction at the nodal planes is compensated by strong in-phase interactions between hydrogen AOs. This HOMO is more stable than the HOMOs of the two ions with heteroatoms attached. |  |

|

| [N(CH3)3(CH2OH)]+ This HOMO is more localised than the tetramethyl ammonium HOMO, and features a distorted d orbital shaped section around the OH carbon. A lot of electron density is featured around the the C-OH group, indicating that this a more reactive part of the molecule. Strong through-bond interaction takes place between the nitrogen and the hydroxyl carbon. There is strong anti-bonding character around the C-OH group though, as can be seen clearly with the out-of-phase lobes. There is also strong anti-bonding interaction at the nitrogen centre. |  |

|

| [N(CH3)3(CH2CN)]+ This is a very localised MO, especially considering the fact that it is higher in energy than the other occupied orbitals. Most of the electron density is centred on the CN group, and this suggests that the CN group is the most reactive part of the molecule. The MO is vary symmetrical in shape for such a high energy orbital, and a flat nodal plane runs down the middle of the CN bond, intersecting the central nitrogen atom. |  |

|

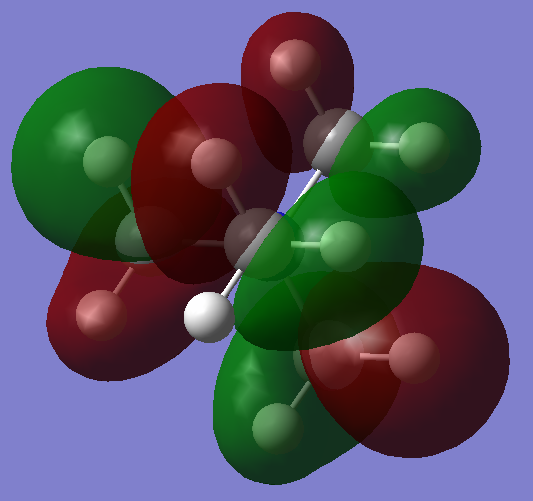

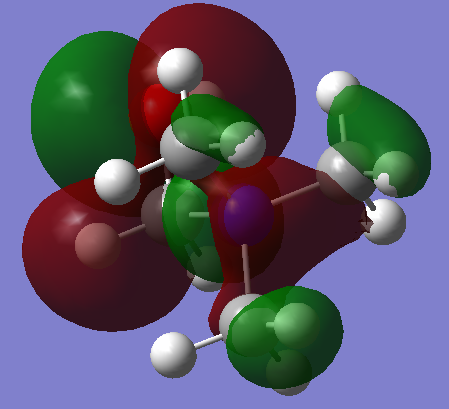

LUMO orbitals are especially important for cations because they give an indication as to how the molecule can accept electrons from electron donors such as anions.

| LUMO Image 1 | LUMO Image 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| [N(CH3)4]+ This is a very delocalised orbital, with four nodal planes. The orbital shows the anisotropic nature in which the molecular cation would interact with anions, but also that it could accept electrons from many directions. Interestingly this orbital seems to have more bonding character than the HOMO, but with more nodal planes, each with a large curved surface area, the anti-bonding interactions outweigh this. The MO is very symmetrical, and if slight deviations due to the calculations are ignored, it has Td symmetry. Lobes can be seen extending from each methyl group away from the molecule, and these points may well be filled by donated electrons. |  |

|

| [N(CH3)3(CH2OH)]+ The OH group destroys the symmetry of the tetramethyl ammonium ion, although the MO has many similarities, and the three methyl groups still have lobes extending from them. It is likely that donating species would be directed towards the three methyl groups, and this is to be expected, as oxygen is a very poor Lewis acid. The hydroxyl hydrogen removes much of the symmetry, as it cannot be reflected in the mirror plane that would otherwise bisect the oxygen and nitrogen atoms. |  |

|

| [N(CH3)3(CH2CN)]+ This is a more symmetrical LUMO. The orbital arrangement over the CN group resembles a d orbital, and exhibits strong anti-bonding interactions. Four lobes extend from each carbon bonded to the central nitrogen. This LUMO has 5 nodal planes, significantly raising the energy of the MO. Strong antibonding will take place between these nodes and the central region of delocalisation, but this region of delocalisation itself will provide a stabilising force. |  |

|

References

- ↑ http://www.lct.jussieu.fr/manuels/Gaussian98/nl001_tn.htm

- ↑ Misra. Journal of the Electrochemical Society, 1988 , vol. 135, # 11 p. 2780 – 2781

- ↑ Gabriel, Armand; Pelton, Arthur D. Canadian Journal of Chemistry, 1985 , vol. 63, p. 3276 – 3282

- ↑ Demina; Bekhtereva; Garkushin. Russian Journal of Inorganic Chemistry, 2013 , vol. 58, # 9 p. 1138 – 1141

- ↑ A. N. Barrett, G. C. K. Roberts, A. S. V. Burgen, and G. M. Clore. Molecular Pharmacology. 1983, 24, 443-448.