Rep:Module3:jzhao

Module Introduction

In this module, the transition structures in larger molecules will be characterised on potential energy surfaces for the Cope rearrangement and Diels Alder cycloaddition reactions. Molecular orbital-based methods will be used to show the transition state structures, reaction paths and barrier heights.

The Cope Rearragement

The [3,3]-sigmatropic shift rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene occurs in a concerted way via either a "chair" or a "boat" transition structure, with the "boat" transition structure of higer energy. The B3LYP/6-31G(d)level of theory was used to optimise the structure and to calculate the activation energies and enthalpies, which were in good agreement with experimental values.

Optimising the Reactants and Products

a)

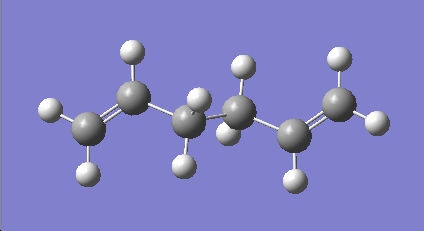

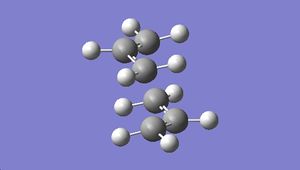

A molecule of 1,5-hexadiene with a.p.p conformation for the central four C atoms was drawn. The geometry was optimised using HF/3-21G with the %mem under the Link 0 tab changed to 250 MB:

# opt hf/3-21g geom=connectivity app_opt 0 1 C etc...

The optimisation ended with an error message shown as below:

The optimisation was carried out again with the %mem set to 6MB giving the optimised geometry shown in figure 1.a.2:

The summary and the symmetry of the molecule were viewed: The optimised structure gives an energy of -231.69254 a.u. and a Ci symmetry.

b)

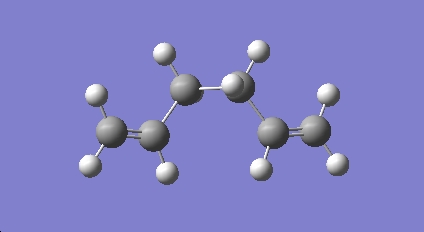

A new molecule of 1,5-hexadiene with gauche conformation for the central four C atoms was drawn. The same optimisation method as for a) (HF/3-21G) was applied to this molecule.

The summary and the symmetry of the molecue were viewed: The optimised structure gives an energy of -231.69153 a.u. and a C2 symmetry. This gauche structure has a higher energy (~0.001 a.u. or 2.65 kJ/mol higher) than the a.p.p structure optimised in a).

c)

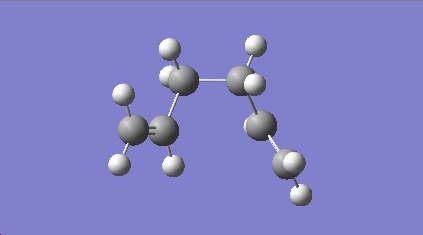

Based on the results from above, one might give the conclusion that the a.p.p conformations is more stable than the gauche ones and the lowest energy conformation might be an a.p.p comformation. However, it is shown in Appendix 1 that the conformation with the lowest energy is gauche3 conformer with the total energy of -231.69266 a.u. and a symmerty of C1. In order to create the lowest energy conformer, a new molecule of 1,5-hexadiene with gauche conformation for the central four C atoms was drawn first and then it was modified to resemble gauche3 conformer by defining the dihedral angles (changing the position of C=C double bonds). The HF/3-21G optimisation method was applied giving the geometry:

The optimised structure gives an energy of -231.69266 a.u. and a C1 symmetry. The geomergy, total energy and symmetry are the same as those of gauche3 conformer in appendix 1, confirming gauche conformer 2 to be the lowest energy conformer.

d)

The structures, energies and symmetries of the optimised confomers in a),b)&c) were compared to the those of conformers shown in Appendix 1.

1 A.p.p conformer is the same as anti2 conformer with an energy of -231.69254 a.u. and a Ci symmetry.

2 Gauche conformer 1 is the same as gauche4 conformer with an energy of -231.69153 a.u. and a C2 symmetry.

3 Gauche conformer 2 is the same as gauche3 conformer with an energy of -231.69266 a.u. and a C1 symmetry.

e)

The Ci anti2 conformer has already located, the same as a.p.p conformer optimised in a).

f)

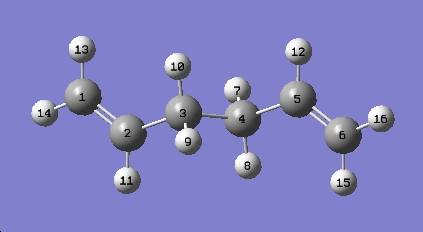

The anti (or a.p.p) conformer was reoptimised using the higher level DFT-B3LYP/6-31G(d) method to obtain a better optimised geometry:

# opt rb3lyp/6-31g(d) geom=connectivity app_opt2 0 1 C etc...

The DFT-B3LYP/6-31G(d) optimised structure has an energy of -234.61172 a.u., which is much lower than the HF/3-21G optimised structure with an energy of -231.69254 a.u.. The overall structure does not change too much, as both strutures have the same symmerty, Ci. Small changes in bond lengths, bond angles and dihedral angles were observed and concluded in the table below:

| Table 1.f - Comparison of HF/3-21G and DFT-B3LYP/6-31G(d) Optimised Geometries | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Lengths | HF/3-21G | DFT-B3LYP/6-31G(d) | Bond Angles | HF/3-21G | DFT-B3LYP/6-31G(d) | Dihedral Angles | HF/3-21G | DFT-B3LYP/6-31G(d) |

| C1=C2 / Å | 1.32 | 1.33 | C1-C2-C3 / ° | 124.8 | 125.3 | C1-C2-C3-C4 / ° | -114.7 | -118.5 |

| C2-C3 / Å | 1.51 | 1.50 | C2-C3-C4 / ° | 111.4 | 112.7 | C2-C3-C4-C5 / ° | 180.0 | 180.0 |

| C3-C4 / Å | 1.55 | 1.55 | C3-C4-C5 / ° | 111.4 | 112.7 | C3-C4-C5-C6 / ° | 114.7 | 118.5 |

| C4-C5 / Å | 1.51 | 1.50 | C4-C5-C6 / ° | 124.8 | 125.3 | |||

| C5-C6 / Å | 1.32 | 1.33 | ||||||

g)

A frequency calculation was run based on the optimized B3LYP/6-31G(d) a.p.p structure by selecting Frequency under the Job Type tab:

# freq rb3lyp/6-31g(d) geom=connectivity app_freq 0 1 C

The vibrational frequencies modes were viewed by selecting Vibrations under the Results menu. No imaginary (negative) frequencies were observed. The IR spectrum was shown as below:

The log file was viewed the energy data under vibrational temperatures was found in the Thermochemistry section:

i) Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies= -234.469183 ii) Sum of electronic and thermal Energies= -234.461846 iii)Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies= -234.460902 iv) Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies= -234.500726

Optimising the Reactants and Products

a)

An allyl fragment (CH2CHCH2) was drawn in Gaussview and optimised using the HF/3-21G method.

An allyl fragment (CH2CHCH2) is drawn in GaussView and optimised using the HF/3-21G method:

# opt hf/3-21g geom=connectivity allyl_opt 0 2 C etc...

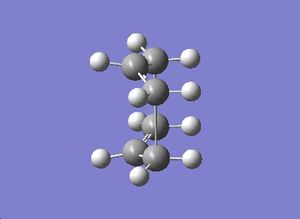

A chair transition state was created by copying and pasting the optimised allyl fragment twice to a new Gaussview window. The two fragments were oriented so that they look roughly like the chair transition state. The distances between the terminal ends of the two allyl fragments were set to 2.2Å.

b)

The chair transition state was optimised and the vibrational frequcies calculated using HF-3/21G method. Opt+Freq, then Optimization to a TS (Berny) and calculate the force constants Once were selected under job type tab. Opt=NoEigen was typed in the Additional keyword section.

# opt=(calcfc,ts,noeigen) freq hf/3-21g geom=connectivity chair_ts_opt+freq 0 1 C

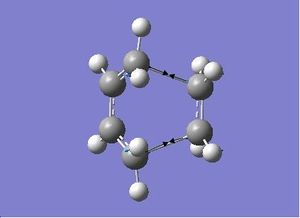

The optimised structure was shown below:

|

|

|---|

The vibrational frequency modes were viewed. An imaginary frequency of magnitude -818 cm-1 was observed, which corresponds to the Cope rearrangement:

c)

The guessed chair transition state was created again. The input file was edited with the bond breaking/forming distances set to 2.2Å using Redundant Coord Editor and the transition state was optimised again using another method - the frozen coordinate method:

# opt=modredundant hf/3-21g geom=connectivity chair_ts_FCopt 0 1 C etc...

The optimised structure is very similar to that optimised in section (b), except the bond breaking/forming distances are fixed at 2.2 Å.

d)

The chair transition state input file was edited in Redundant Coord Editor (choosing Bond instead of Unidentified and Derivative instead of Add). The bond breaking/forming distances were further optimised:

# opt=(ts,modredundant) rhf/3-21g geom=connectivity chair_ts_FCopt2 0 1 C etc...

The bond breaking/forming bond lengths were viewed and the structure was compared to the one optimised in section (b): The structure optimised using the reduntant coordinate editor has a total energy of -231.615 a.u., which is slightly (0.004 a.u.) higher thant the one optimised by computing the force constants. The structures of the two optimised transition state are very similar. The small differences are concluded in table 2.d.

| Table 2.d - Comparion of structrues of chair transition state obtained by computing the force constants and using the redundant coordinate editor | ||

|---|---|---|

| Computing the force constants | Redundant coordinate | |

| bond breaking/forming distances/ Å | 2.02 | 2.20 |

| C-C bond in allyl fragments/ Å | 1.39 | 1.38 |

| C-C-C bond angle / ° | 120.5 | 122.0 |

e)

The optimised Ci reactant molecule (a.p.p confomer) was used as the reactant. The same molecule was added to the MolGroup by selecting File\New\Add to MolGroup as the product. The numbering of the atoms on both molecules was changed as the figure shown below:

The QST2 calculation was carried out to find the transition state between the reactant and product:

# opt=(qst2,noeigen) freq hf/3-21g geom=connectivity Boat_opt 0 1 C etc...

The output of the calculation gives a more dissociated chair transition state, indicating the job failed to find the boat transition state. The reason for the failure is that the QST2 calculation only interpolate linearly between the two structure. As the structures of the reactant and product differ much from the boat transition state, it is unable to find the boat transition state.

In order to find the boat transition state, the reactant and product structures were modified: 1.the central C-C-C-C dihedral angle (C2-C3-C4-C5)was set to 0° 2.the bond C-C-C bond angles (C2-C3-C4 and C3-C4-C5) were set to 100°

The QST2 calculation was run again and the boat transtion was found:

|

|

|---|

The vibrational frequency modes were viewed. An imaginary frequency of magnitude -840 cm-1 was observed, which corresponds to the Cope rearrangement via boat transition state:

f)

Comparing the trasition state sturctures to the 1,5-hexadiene structures in Appendix1, it was guessed that the chair transition state was connected to the gauche2 sturcture and the boat transition state best resembles the gauche1 structure. To confirm the conncetion, an Intrinisic Reaction Coordinate or IRC method can be used.

The optimised chair transition structures from b) was subjected to the IRC method. The calculation was set to compute in the forward direction as the reaction coordinate is symmetrical. The calculation of force constants was set to always. The number of points along the IRC was set to 50.

# irc=(forward,maxpoints=50,calcall) rhf/3-21g geom=connectivity chair_ts_IRC 0 1 C etc...

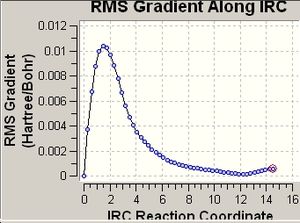

The total energy along IRC and RMS gradient along IRC diagrams were viewed:

|

|

|---|

As is shown in the energy and RMS gradient diagrams, the energy hasn't reached a minimum and the RMS gradient hasn't reached 0 (i.e. the optimisation hasn't reached a minimum geometry yet. In oreder to obtain a minium geometry, the IRC calculation was carried out again with the number of points set to 200. The same procedures were applied to the chair transiton state. The optimisations converge to give minimum geometries shown as below:

|

|

|---|

At the beginning of this section the guessed connection is that the chair transition state was connected to the gauche2 sturcture and the boat transition state best resembles the gauche1 structure. However, this guess is not correct. According to the diagrams above, the chair transition state resembles the gauche2 sturcture and the boat transition state resembles the gauche3 structure. The comparison of the total energy values of the minimum geometries to the the gauche structures further confirms the connection. The IRC method provides a way to find the local minimum by following the minimum energy path from a transition structure on a potential energy. surface.

g)

The geometries of both chair and boat transition states based on HF/3-21G calculation were reoptimised and the frequencies recalculated using the B3LYP/6-31(d) method:

# opt freq rb3lyp/6-31g(d) geom=connectivity chair_ts_opt+freq2 0 1 C etc...

The energy differences between reactants and transtion states and the activation energies were concluded in Table 1.g.1 and 1.g.2.

| Table 1.g.1 - Energy difference differences between reactants and transition states (in hartree) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G(d) | |||||||

| Electronic energy | Sum of electronic and zero-point energies | Sum of electronic and thermal energies | Electronic energy | Sum of electronic and zero-point energies | Sum of electronic and thermal energies | |||

| at 0 K | at 298.15 K | at 0 K | at 298.15 K | |||||

| Chair TS | -231.619 | -231.466 | -231.461 | -234.611 | -234.414 | -234.409 | ||

| Boat TS | -231.603 | -231.451 | -231.445 | -234.543 | -234.402 | -234.396 | ||

| Reactant (anti2) | -231.693 | -231.540 | -231.533 | -234.612 | -234.469 | -234.462 | ||

| Table 1.g.2 - Summary of activation energies (in kcal/mol) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF/3-21G | HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G(d) | B3LYP/6-31G(d) | Expt. | ||||

| at 0 K | at 298.15 K | at 0 K | at 298.15 K | at 0 K | ||||

| ΔE (Chair) | 46.44 | 45.18 | 34.51 | 33.25 | 33.5 ± 0.5 | |||

| ΔE (Boat) | 55.85 | 55.22 | 42.04 | 41.42 | 44.7 ± 2.0 | |||

Both the activation energies via chair and boat transition states calulated using HF/3-21G method are much larger than the lit. values. The activation energies calculated using the higer level method - B3LYP/6-31G(d)method are very close to the lit. values (0.5 kcal/mol larger for the chair transition and within the range for the boat transition), indicating the computational calculation is a quite accurate method to work out the activation energies for this reaction.

The Diels Alder Cycloaddition

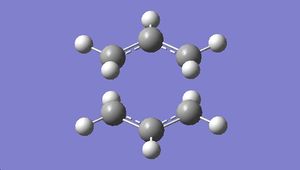

In this exercise, the methods described in the previous sections will be used to characterise transition state structures of Diels Alder Cycloaddition of Ethylene and Butadiene. The MOs of the diene, dienophile and trantion state were computed and viewed to explain the reaction.

i)

The cis butadiene and ethylene were drawn in GaussView and optimised using AM1 semi-empirical molecular orbital method:

# opt am1 geom=connectivity butadiene_opt 0 1 C etc...

The HOMOs and LUMOs were computed: Select Edit\MOs. Select the HOMO and the LUMO from the MO list. Click the tab Visualise, then Update.

|

|

|

|

|---|

The symmetry of the HOMOs and LUMOs were determined:

1. For butadiene, HOMO: anti-symmetric LUMO: symeetric

2. For ethylene, HOMO: symmetric LUMO: anti-symeetric

ii)

A MolGroup file was created using the butadiene and ethylene as reactants and cyclohexene as product. All the atoms were renumbered as shown in figure 3.2.a.

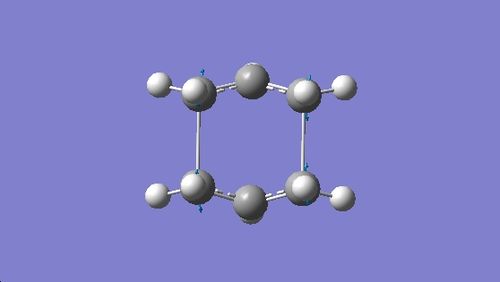

QST2 calculation was carried out to find the transition state for the Diels-Alder Reaction:

# opt=(qst2,noeigen) freq am1 geom=connectivity diels_alder_ts_opt+freq 0 1 C etc...

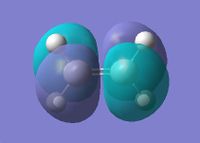

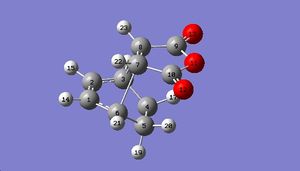

The optimised trasition state was shown below:

The geometry data (bond lengths, bond angles and dihedral angles) were viewed. The bond lenghts of the partly formed C-C bonds (C1-C6 and C4-C5) are found to be 2.12Å. The typical sp3-sp3 and sp2-sp2 bond lengths are 1.54Å and 1.34Å respectively from literature [1]. The van der Waal's radius of carbon atom is 1.70Å.[2] The bond length of the partly formed C-C bond (2.12Å) is shorter than the sp3-sp3 bond (1.54Å) but longer than the sum of the radii of two carbon atoms (3.40Å), which indicates that the two carbon atoms are neither seperate atoms nor do they form a real C-C bond.

The vibrational frequency modes were viewed. An imaginary vibration with the frequency of -956 cm-1 was observed, which corresponds to the Diels-Alder reaction. The vibration indicates taht the formation of the two bonds are synchronous (i.e. forming at the same time). The lowest positive frequency is at 147 cm-1. This vibration is asymmetric bending mode involving the rotation of the ethylene component around the two partly formed C-C bonds.

|

|

|---|

The HOMO and LUMO of the transition state were computed and viewed, the symmetry of the HOMO of transition state was determined to be anti-symmetric and LUMO to be symeetric with respect to the nodal plane.

|

|

|---|

For an allowed Diels-Alder reaction to happen, the HOMO of one fragment should interact with the LUMO of the other fragement. In this case, the HOMO of butadiene and the LUMO of ethylene are both anti-symmetric. As orbitals with same symmetry and right orientation tend to have a large overlap density, the HOMO/LUMO orbitals can interact strongly to form an anti-symmetric transition state HOMO. Same theory can be applied to the LUMO of transtion state: the symmetric LUMO of butadiene and HOMO of ethylene can interact to form symmetric LUMO of transition state. The MO diagram is shown below:

iii)

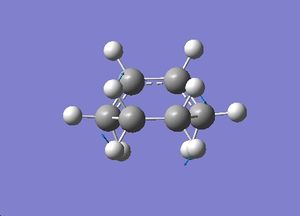

The regioselectivity of the Diels Alder Reaction of Cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride was studied in this section. The reaction gives the endo adduct as major product. As it is a kinetically controlled reaction, the endo transition state should be lower in energy. Computational techniques were used to find the structures of transition states, calculate the energies and compute the MOs.

The input file was created with Cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride as reactants and exo adduct as product. The input file for endo adduct was created as well. QST2 calculation was carried out to find the transition states for both reactions:

# opt=(calcfc,qst2,noeigen) freq am1 geom=connectivity exo_opt+freq 0 1 C etc...

|

|

|---|

The tatoal energy data and geometry data for both transition states were concluded in the table below:

| Table 3.1 - Comparion of energy and geometries of exo and endo transition states | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Energy (a.u.) | Bond lengths (Å) | |||||||

| Partly formed C-C | C=C breaking on dienophile | C=C breaking on diene | C=C foming on diene | C-C (near C=C) | C-C (away from C=C) | C-C through space distances* | ||

| Exo transition state | -0.0504 | 2.17 | 1.41 | 1.39 | 1.40 | 1.49 | 1.52 | 2.95 |

| Endo transition state | -0.0515 | 2.16 | 1.41 | 1.39 | 1.40 | 1.49 | 1.52 | 2.89 |

C-C through space distances*: the C-C distantces between the -(C=O)-O-(C=O)- fragment of the maleic anhydride and the C atoms of the “opposite” -CH2-CH2- for the exo and the “opposite” -CH=CH- for the endo

According tot the table, the calculated total energy of endo transition state is slightly lower (0.0011 a.u.) than the chair transition state, which is in consistance with the experimental results. The bond lengths of the C-C or C=C bonds are very similar. The C-C through sapce distance is shorter for the exo transition state, indicating ineraction between the two C-O-C part and the rest part is stronger for the exo structure. Thus the exo sturcture is more more strained. This helps explain the relative stability of the two transition states.

The HOMO and LUMO of the transition states were computed and viewed, the symmetry of HOMOs and LUMOs were determined to be anti-symmetric with respect to the nodal plane.

For the endo transition state, the (C=O)-O-(C=O)part HOMO on the middle oxygen has very similar nodal properties to the 6-membered ring part of the HOMO (i.e. the parity of the orbital on one side of the nodal plane are the same). Orbitals with similar nodal properties can overlap. Thus the (C=O)-O-(C=O)part HOMO on middle oxygen and 6-membered ring part of the HOMO can interact. This is not found in the exo case as orbital density was found around the middle oxygen. Such kind of overlap is called secondary orbital overlap. The secondary orbital overlap is another reason for the relative high stability of endo transition state.

Log Files

The log files can be found at D-space: 1. The Cope Rearragement: [1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13] 2. Diels-Alder Reaction: [14][15][16][17][18][19]