Rep:Module1:jyc08module1

Module 1 - Part 1

The objective of this module will be to undertake molecular modelling of organic molecules in order to consider their structures and reactivity. This may allow us to predict their reactivity .

The selection of molecules that will be considered here will illustrate the diversity of molecular modelling.

The module will end with a mini-research exercise in order to determine whether the structure of my final product is correct.

Using Molecular Mechanics to predict the geometry and regioselectivity of:

- the hydrogenation of cyclopentadiene dimer

- the stereochemistry of nucleophilic addition to two different pyridinium rings (NAD+ analogues)

- the conformation/atropisomerism of a large ring ketone intermediate in one synthesis of the anti-cancer drug Taxol

Background on Cyclopentadiene

Cyclopentadiene exists as a dimer in either the (1) exo- or (2) endo- form:

When the cyclopentadiene dimer is hydrogenated, the initial product will be either (3) or (4):

The tetrahydro derivative (shown below) is only formed after prolonged hydrogenation:

The following exercise will involve calculating the geometries and energies of the molecules (1) - (4), and therefore to deduce from the energies the relative stabilities of the pairs (1)-(2) and (3)-(4).

The lower the energy of a particular structure, less strained/hindered that structure is and hence the more thermodynamically stable.

Reactivity towards cyclodimerisation to form (1) or (2), or partial hydrogenation to form (3) or (4), is a result of either thermodynamic control (product stability) or kinetic control (transition state stability).

Molecular Modelling of molecules (1) and (2)

It is known that the room temperature Diels-Alder dimerisation of cyclopentadiene specifically forms the (2) endo- rather than the (1) exo- isomer.

In order to try to explain this, both molecules (1) and (2) were drawn in ChemBio3D and the MM2 force field option was used to optimise their geometries.

| Stretch | Bend | Stretch-Bend | Torsion | Non-1,4 VDW | 1,4-VDW | Dipole/dipole | Total Energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.2835 | 20.5821 | -0.8378 | 7.6546 | -1.4237 | 4.2417 | 0.3774 | 31.8778 kcal/mol (1) |

| 1.2430 | 20.8574 | -0.8330 | 9.5117 | -1.5557 | 4.3297 | 0.4489 | 34.0020 kcal/mol (2) |

Dimerisation of Cyclopentadiene: Thermodynamic vs. Kinetic

It is found that the (1) exo- dimer is just over 2 kcal/mol lower in energy than the (2) endo- dimer. The difference in energy being mainly due to the torsion energy of each molecule.

Therefore we can conclude that (1) exo- isomer is thermodynamically more stable than (2) endo- so we can conclude that the thermodynamic dimerisation of cyclopentadiene should give a predominant product of the (1) exo- isomer, bearing in mind that thermodynamic conditions are reversible.

However, the opposite is observed at room temperature: at room temperature this dimerisation produces the thermodynamically least stable isomer (2) which indicates that the reaction is under kinetic control. The (heat) energy that is present at room temperature is sufficient to allow the more kinetically unstable ismomer to form, which is the one with the higher energy transition state. We know that kinetic conditions are irreversible, therefore this dimerisation reaction produces specifically isomer (2), the least thermodynamically stable.

It is incidental in the case of cyclopentadiene that the thermodynamic and kinetic products are different, giving one isomer under thermodynamic conditions and the other product under kinetic conditions.

Molecular Modelling of molecules (3) and (4)

In light of the above discussion, we know that at room temperature the cyclopentadiene dimer exists in the endo-form (2). Molecular modelling will now be carried out upon the two products of the partial hydrogenation of the endo-isomer (2) in order to determine which one of the two double bonds in (2) are 'easier', ie. lower energy, to hydrogenate.

| Stretch | Bend | Stretch-Bend | Torsion | Non-1,4 VDW | 1,4-VDW | Dipole/dipole | Total Energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.2778 | 19.9223 | -0.8360 | 10.7886 | -1.2542 | 5.6306 | 0.1620 | 35.6910 kcal/mol (3) |

| 1.1118 | 14.5097 | -0.5553 | 12.4944 | -1.0563 | 4.5109 | 0.1406 | 31.1558 kcal/mol (4) |

It is seen that molecule (4) is about 4kcal/mol lower in energy than molecule (3), with the main contributing factors to the difference in energy being due to the Bending energy and the Torsional energy.

Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

In order to consider which one of (3) and (4) would be more easily formed from the endo-isomer (2), the relative total energies of the reactants and the products should be considered:

It can be seen that according to the optimisation calculations that were previously carried out, the reaction (2) to (3) would involve an increase in thermodynamic energy whereas the reaction (2) to (4) would involve a decrease in thermodynamic energy.

Therefore, thermodynamically speaking, the hydrogenation of the double bond in the bridged ring to give (4), is more thermodynamically favoured than the hydrogenation of the double bond in the un-bridged ring, to give (3). This would indicate that the thermodynamic hydrogenation of the double bond in the un-bridged ring is 'easier' to hydrogenate than the other.

However, once again we must consider whether this reaction will be done under thermodynamic conditions or kinetic conditions. As we saw before, in the dimerisation of cyclopentadiene, the product of the reaction under thermodynamic conditions is very different from the product of the reaction under kinetic conditions. This might also apply here, however the computational modelling method that is being used in this experiment does not offer any insight into the kinetics of the reaction, ie. the relative energies of the transition states. It simply gives the relative energies of the final products.

Module 1 - Part 2

Stereochemistry of Nucleophilic additions to a pyridinium ring (NAD+ analogue)

The following exercise will make use of the same molecular modelling method used above in order to try to explain the stereoselectivity of two particular reactions.

Considering the first reaction, it is known[1] that the reactant (5) will undergo attack at the C4 position of the pyridinium ring by Grignard reagents to give highly stereoselective products, where the R group from the Grignard ends up at position 4, anti to the chiral centre H atom in the product (6). It has been proposed that this stereoselectivity is the result of chelation control. The mechanism will be further discussed and illustrated in the following exercise.

The second reaction is similar to the first reaction as the C4 position of a pyridinium ring is being attacked by a nucleophile. This stereoselctive reaction will also be further explored in the exercises to follow.

Nucleophilic Addition of Grignard to Pyridinium Ring

As mentioned above, the reaction of (5) to (6) is believed[1] to be a result of coordination between the Mg of the Grignard reagent and the amide oxygen. This is followed by conjugate delivery of the R group, in this case methyl, from the Grignard to C4 off the pyridine ring, to give the magnesium enolate. Finally, the Mg dissociates from the molecule to deliver the product (6) where there is no longer a positive charge on the pyridine nitrogen.

The literature proposes that this reaction, instead of taking place in discrete steps as shown, actually takes place in a concerted reaction via a 6-membered transition state. This would explain the high stereoselectivity, as it has been found that the amide carbonyl actually lies above the plane of the pyridine ring and therefore chelation can only give the stereochemistry as shown in (6). It is proposed that there are two conformational minima, the first having the amide carbonyl above the pyridine ring plane and the second having the amide carbonyl and the pyridine ring co-planar. It is claimed that there is no conformation in which the carbonyl is below the plane of the ring.

However, as it was found that this reaction is stereoselective, and not stereospecific, it was proposed that any minor products formed in this reaction are simply the result of mechanisms which do not involve a 6-membered transition state.

Literature also cites that there is very little flexibility in the 7-membered ring.

Molecular Modelling of molecule (5)

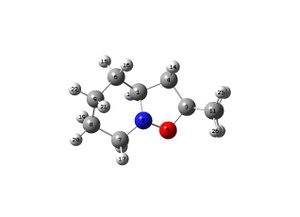

The structure of molecule (5) was drawn in ChemBio3D and optimised using the MM2 method. The carbon atoms in the 5-, 6- and 7-membered rings were moved around and repeatedly optimised in order to see which conformations would have the lowest energy. However, the lowest energy conformation seemed to have an energy of 44.6039 kcal/mol, and the following structure:

This structure agrees with that described in the literature as the amide carbonyl is just above the plane of the pyridine ring, with a dihedral angle of 12deg. This supports the suggested mechanism in which the carbonyl oxygen atom chelates to the Mg and subsequently directs the incoming nucleophile to the same face as the carbonyl, to give the product (6).

Repeated optimisation found that the 7-membered ring kept the same conformation after each optimisation, just as literature suggested.

Therefore these energy optimisations of molecule (5) have resulted in a conformational structure which agrees with the proposed chelate mechanism and subsequent stereoselectivity of the nucleophilic addition to this molecule.

It should be noted that it was not possible to carry out an energy optimisation of the Mg-chelated intermediate because the computer program did not recognise the presence of the Mg atom. If the program were improved so that it could recognise the Mg atom, an energy optimisation of the chelated 'intermediate' could be carried out. The energy of this intermediate could then be extrapolated, by Hammond's Postulate, to estimate the energy of the transition state of this reaction and therefore the energy pathway of this reaction mechanism could be better understood.

Nucleophilic Addition of Aniline to Pyridinium Ring

This reaction is stereoselective as in the previous reaction and similarly the stereoselectivity of the incoming nucleophile is thought to be due to the conformation of the amide carbonyl. It was found in literature[2] that the reactant (7) undergoes nucleophilic attack by piperidine and benzylamine to give very highly diastereoselective products of 95% in both cases.

In order to try to explain this observation, the energy of molecule (7) was once again optimised and the resulting conformational structure of the molecule was studied.

Molecular Modelling of molecule (7)

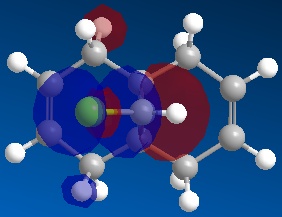

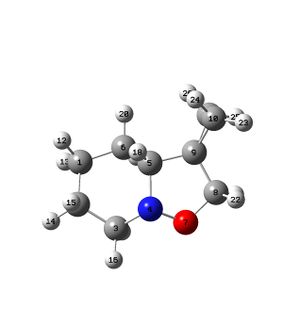

Repeated MM2 optimisation, rearranging of the atoms and adjustment of the dihedral angle on molecule (7) in ChemBio3D gave the following structure:

The energy of this structure is 63.4185 kcal/mol and it can be seen that the dihedral angle between the amide carbonyl group and the pyridine ring is now -20deg. This indicates that the carbonyl group now prefers to be below the plane of the pyridine ring, as opposed to in molecule (5) where it preferred to be above the plane of the pyridine ring.

In order to explain the high selectivity of the reaction of molecule (7) with a nucleophile, the carbonyl group and more importantly, the lone pairs on the oxygen, must be considered. The two lone pairs on the oxygen atom take up a lot of steric space around the molecule, and are expected to hinder the approach of a nucleophile.

The nucleophile in this case is an amine which also possesses a lone pair. Therefore, there are very unfavourable repulsive interactions between the lone pair of the amine and the lone pairs of the oxygen.

In order to avoid these unfavourable repulsive interactions, the carbonyl orientates itself slightly below the plane of the pyridine ring (in this case, 20deg below the ring), and the incoming amine attacks from the opposite plane, to selectively give the product (8). This suggestion agrees with the observations in the literature.

Module 1 - Part 3

Stereochemistry and Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

This exercise focuses on the molecules (9) and (10) which are both intermediates in the synthesis of Taxol:

During the synthesis, only one of the two isomers is formed, but the two are able to isomerise to give the alternative isomer upon standing. This type of isomerism is an example of atropisomerism. The stereochemistry of the product following carbonyl addition will depend on which one of the reactant isomers (9) or (10) is the most stable.

It has also been noted that the subsequent functionalisation of the double C-C bond is very slow.

MM2 optimisation of molecules (9) and (10)

The two molecules were optimised in ChemBio3D using the MM2 optimisation, to give the following energies:

| Molecule | Stretch | Bend | Stretch-Bend | Torsion | Non-1,4 VDW | 1,4 VDW | Dipole/Dipole | Total Energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (9) | 2.7778 | 16.5126 | 0.4453 | 20.6092 | -0.3487 | 13.9404 | 0.1792 | 54.1158 kcal/mol |

| (10) | 2.5382 | 10.6742 | 0.3149 | 19.8135 | -1.4124 | 12.5657 | -0.1803 | 44.3138 kcal/mol |

The optimised structures are shown below:

The energy of molecule (9) is about 5 kcal/mol higher than that of molecule (10).

By considering the 3D structure of molecule (9), it can be seen that the carbonyl pointing up experiences steric clash with numerous hydrogen atoms attached to neighbouring carbon atoms, as well as one of the methyl groups on the bridgeheads. This results in unfavourable steric interactions.

In molecule (10) the carbonyl points down and although it also interacts with the surrounding hydrogen atoms which are attached to neighbouring carbon atoms, the carbonyl is not in close proximity to the methyl groups on the bridgeheads, and therefore does not experience steric clash with these.

Since it is known that the two isomers are able to interconvert at room temperature upon standing, it would be expected that more of the more stable isomer would be present. Therefore, it would be expected that at room temperature, after a certain amount of time, more of (10) would be present.

MMF94 optimisation of molecules (9) and (10)

The two molecules (9) and (10) were further optimised using MMFF94 method in ChemBio3D.

The final energies were as follows:

| Molecule | Final Energy |

|---|---|

| (9) | 77.9302 kcal/mol |

| (10) | 66.33606 kcal/mol |

Once again, it can be seen that the the 'carbonyl up isomer' (9) is higher in energy than the 'carbonyl down isomer' (10). This difference in energy can be argued in the same way as before, by considering the relative amounts of steric clash experienced by the carbonyl in each isomer.

Although the relative energies of the two isomers are the same after using the MM2 and the MMFF94 methods, the absolute values are different, with the final energies obtained from the MMFF94 method being higher than those from the MM2 method.

Slow Reaction of Olefin

Olefin strain energy (OS) is defined as the difference between the strain energy of a particular alekene and its corresponding parent alkane. The OS value is used as a tool in the prediction of stability and reactivity of bridgehead alkenes.

It has been found[3] that some alkenes are in fact less strained than the parent alkane and therefore these alkenes are less reactive than the alkane. This is because the double bond occurs at a bridgehead. These particular alkenes are called 'hyperstable' alkenes.

In order to try to determine the main contributing factor of the stabilisation of the 'hyperstable' molecule (10), its parent hydrocarbon was drawn in ChemBio3D and the energy of the molecule was optimised by the MM2 method. Below are the results from the optimisation:

| Molecule | Stretch | Bend | Stretch-Bend | Torsion | Non-1,4 VDW | 1,4 VDW | Dipole/Dipole | Total Energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (10) | 2.7778 | 16.5126 | 0.4453 | 20.6092 | -0.3487 | 13.9404 | 0.1792 | 54.1158 kcal/mol |

| Alkane | 4.1983 | 20.9848 | 0.9380 | 22.4274 | 2.1770 | 16.8351 | -0.0000 | 67.5607 kcal/mol |

The optimised structure of the alkane is given below:

It can be seen that the alkene molecule (10) is lower in energy than the alkane across all of the categories, resulting in a lower total energy and therefore a 'hyperstable' alkene (10) compared to the its parent alkane.

Apart from Stretch-Bend and Dipole/Dipole, all of the other categories show significant differences in energy between the alkene and alkane.

The stability of the alkene therefore explains why the functionalisation reaction of the double bond in (10) occurs so slowly.

Module 1 - Part 4

Modelling Using Semi-Empirical Molecular Orbital Theory

The following exercise will once again involve the program MM2 in ChemBio3D, which treats a molecule in purely classical terms; and another program MOPAC/PM6 or MOPAC/RM1 will be used to describe the molecular orbitals of the electrons in the molecule in a quantum mechanical treatment.

Regioselective Addition of Dichlorocarbene to Molecule (12)

Literature[4] has reported that the following reaction occurs regiospecifically at the double bond that is endo to the chlorine, on the opposite face of the molecule to the chloropropyl ring:

It is believed that in such a rigid molecule, the observed regioselection occurs due to either orbital or electrostatic control, or due to other considerations involving the transition state.

Molecular Orbitals of Molecule (12)

In order to try to explain the regioselectivity of the above reaction the energy of molecule was optimised and then the energies of the molecular orbitals were determined.

Molecule (12) was firstly optimised in ChemBio3D using the MM2 method to give a minimum energy of 17.8977 kcal/mol:

| Stretch | Bend | Stretch-Bend | Torsion | Non-1,4 VDW | 1,4 VDW | Dipole/Dipole | Total Energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.6170 | 4.7794 | 0.0412 | 7.6470 | -1.0821 | 5.7831 | 0.1121 | 17.8977 kcal/mol |

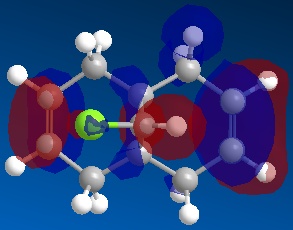

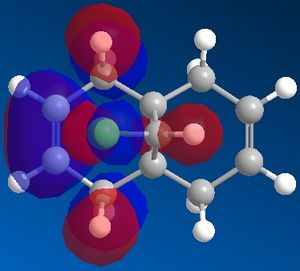

Following this, MOPAC/PM6 was run to give the molecular orbitals of the molecule, of which the following were studied:

| HOMO-1 | HOMO | LUMO | LUMO+1 | LUMO+2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

It can be seen that molecule (12) has a plane of symmetry sitting on top of, and parallel to, the C-Cl bond, 'slicing' the molecule into two halves "top" and "bottom" as shown. From this symmetry of molecule (12) it would therefore be expected that the molecular orbitals (MOs) would also have the same relative symmetry, with the MOs at the "top" expected to be a mirror image of the MOs at the "bottom".

It can be seen from the MOs obtained above that this is not the case and in all of the shown MOs, there is noticeable asymmetry between the top and bottom half of the MOs.

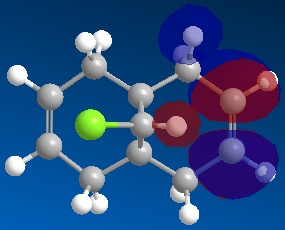

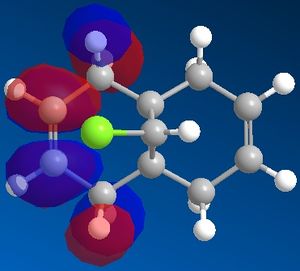

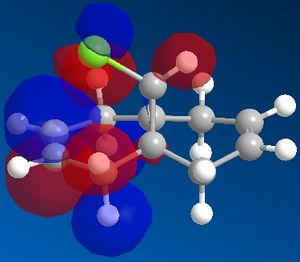

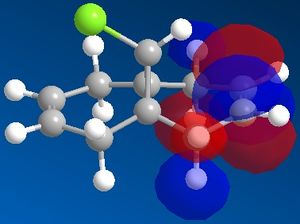

Therefore, in order to see whether MOs could be obtained with the expected symmetry, the molecule was once again optimised by MM2 and this time, the MOPAC/RM1 method was used to calculate the MOs.

| View | HOMO-1 | HOMO | LUMO | LUMO+1 | LUMO+2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top |  |

|

|

|

|

| Side |  |

|

|

|

|

It can now be seen that the MOs do in fact have symmetry about the plane of symmetry that was described earlier. Symmetry in which the phase of the "bottom" half of the molecule mirrors the "top" half of the molecule is evident in the HOMO-1, HOMO and LUMO MOs. The remaining MOs, LUMO+1 and LUMO+2, have exactly the opposite of this, such that the phase of the "bottom" half is the opposite of the phase of the "top" half (considering the view of the molecule from the Top).

It can be seen from the MOs that the two alkenes in the molecule are very different.

The HOMO shows that the highest energy electrons are located on the endo-alkene and partly on the chlorine atom, as well as some surrounding C-H bonds. Therefore electrophile are most likely to attack at the endo-alkene and hence the reaction with dichlorocarbene is endo-selective.

The HOMO-1 shows that the electron density which is present on the exo-alkene is lower in energy than the electron density on the endo-alkene.

Therefore, the MOPAC/RM1 method is able to discriminate between the two alkene bonds, showing that the endo-bond is the most nucleophilic.

Literature[5] concludes that the reason for the regioselective nature of this particular reaction is a stabilising interaction between the C-CI σ* orbital and the exo C=C π-orbital. This can be used to explain why the exo π-orbital is lower in energy than the endo π-orbital. It can be seen from the MOs directly above that the exo π-orbital (HOMO-1) has the phases of the MOs in such a way as to be able to constructively interact with the C-Cl σ* orbital (LUMO), because they are located roughly anti-periplanar to one another. This type of interaction therefore stabilises the resulting exo π-orbital. This interaction is not possible with the endo π-orbital because the endo π-orbital (HOMO) is not positioned anti-periplanar to the C-Cl σ* orbital and therefore is not able to undergo this interaction, hence the endo π-orbital is higher in energy and is the resulting HOMO of this molecule.

It must be pointed out that the MOs shown directly above represent the molecular orbitals after such interactions have occurred. Strictly speaking, the HOMO-1 MO shown does not really represent the exo C=C π-orbital alone. Instead, it shows the exo C=C π-orbital after it has undergone interaction with the C-Cl σ* orbital. In the above description of the orbital interactions, references were made to the depicted MOs on the assumption that the MOs being described (C-CI σ*, exo C=C π and endo C=C π) still resemble those depicted.

Vibrational Frequencies of Molecule (12)

In order to verify the suggestion that there is orbital interaction between the C-Cl σ*-orbital and the exo C=C π-orbital, the C-Cl bond stretching frequency of molecule (12) and its hydrogenated equivalent (in which only the exo C=C bond is hydrogenated) was studied to see whether or not there was a difference in bond strength between the two molecules.

The MOPAC/RM1 method was run in ChemBio3D for both molecule (12) and its hydrogenated counterpart, and the following bond frequencies were found for both molecules:

| Molecule | C-Cl Stretch | Anti C=C Stretch | Syn C=C Stretch |

|---|---|---|---|

| (12) | 770.793 | 1737 | 1757.43 |

| Hydrogenated product | 779.931 | 1753.76 |

It can be seen that in molecule (12), the C-Cl bond is weaker than in its hydrogenated counterpart. This supports the idea of interaction between the C-Cl σ*-orbital and the exo C=C π-orbital because upon donation of electron density from the C-Cl σ*-orbital into the exo C=C π-orbital, the C-Cl bond would be expected to become weaker, which is observed from the vibrational frequency values.

There is a slight difference between the vibrational frequency of the endo-C=C in molecule (12) and the hydrogenated molecule. This was unexpected since there was no expected interaction between the C-Cl σ*-orbital and the endo C=C π-orbital. This might have resulted from molecule (12) not being optimised to the lowest possible energy.

Module 1 - Part 5

Structure based Mini project using DFT-based Molecular orbital methods

The aim of the following project will be to study a particular reaction in which the the reactants give rise to mixture of two or more isomeric products. Consideration will be directed towards the methods by which the isomeric mixture of product can be analysed in order to determine which isomer may have formed (as the major product).

The analytical methods which will be considered here will be mainly spectroscopic: IR and 13C NMR.

It was suggested that conformationally rigid molecules would be the best type to study, because the computational calculations that will be carried out might not be able to successfully run a calculation for a molecule which is very conformationally mobile.

Tetraisoxazole-5-spirocyclopropanes

The following general reaction was chosen from literature[6] for study in this exercise:

This is a cycloaddition reaction of a 1,3-dipolar nitrone 1 to methylenecyclopropane 2, to give a mixture of two regioisomers 3 and 4. This reaction was carried out using three different nitrone derivatives a, b and c in which the cycloadditions were carried out at 60degC over two days to give good yields of product (69-86%), which consisted of mixtures of the two regioisomers.

The focus of this exercise will be on the reaction involving the c derivative of nitrone:

The derivative c was chosen because it was preferable in this exercise to study a molecule which was conformationally rigid.

The GIAO method that will be used to predict the 13C NMR spectrum is known to be very sensitive to the conformation of a molecule. If a molecule can exist as many different conformations, all of these will need to be scanned and this would lead to a very long scanning time. The following exercise will therefore focus on conformationally simple molecules.

It can be seen that the R1 and R2 groups of a are not cyclic (as in b and c) and that they are not both extremely bulky. Therefore these substituents do not act very well as conformational locks and may be able to give rise to many conformations, which is undesired in this exercise. The two substituents Ph and Me can also undergo bond rotation so it was decided that a would not be the focus of this exercise because these substituents would make the analysis slightly complex.

Both b and c were initially considered for study as they both contain a cyclic substituent which would minimise the number of different conformations. It was finally decided to not choose b for study because the cyclic substituent features two further Me substituents, which might make the NMR and IR analysis slightly more complex than c. Therefore, c was chosen as the reaction for study in the following exercise.

According to literature[6], the 5-spiro regioisomer 3c is the predominant product (90%). It was found that the two isomers 3c and 4c cannot be separated by distillation or flash column chromatography. However, it is known that 3 is less stable than 4, and is therefore able to undergo a rearrangement reaction as shown:

It is claimed in literature[6] that 4 more stable because of the lack of a cyclopyopyloxy system which supplises the driving force of the observed rearrangement. Therefore, the isolation of 4 is possible by flash column chromatography after the regioisomer 3 has undergone such rearrangement.

The following exercise will focus on the spectroscopic methods which can allow differentiation between the two isomers.

13C NMR analysis

Each molecule 3c and 4c was optimised to give the lowest energy possible, and then the respective 13C NMR computational analysis was carried out on the optimised structures. The NMR data obtained was then be compared to literature data to see whether or not they matched.

Molecules 3c and 4c were drawn into ChemBio3D and initially optimised using the MM2 method to give the following energies:

| Molecule | Stretch | Bend | Stretch-Bend | Torsion | Non-1,4 VDW | 1,4 VDW | Dipole/Dipole | Total Energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3c | 0.6753 | 7.5487 | 0.1116 | 9.8106 | -2.4176 | 8.7397 | 1.2832 | 25.7517 kcal/mol |

| 4c | 0.9051 | 6.4561 | 0.1445 | 13.1496 | -2.3905 | 9.0769 | 1.5658 | 28.9074 kcal/mol |

The MM2 optimised molecules had the following structures:

MM2 optimisation gave 4c a higher energy than 3c, which seems to contradict the observations that 3c are less stable and hence undergo rearrangement. Once again, this demonstrates the need to distinguish between thermodynamic and kinetic stability. In this example, since these two observations (the first from literature[6] and the second from MM2 optimisation) show conflicting results, this indicates that between the molecules 3c and 4c, one of them is thermodynamically more stable, and the other is kinetically more stable.

The MM2 optimised molecules were then prepared for another refinement optimisation using the Gaussian DFT/mpw1pw91 method in ChemBio3D. The basis set was chosen to be 6-31G(d,p), and the Gaussian input file was subsequently edited for Geometry Optimization.

The Gaussian optimised structures are shown below:

It can be seen that the structure of 3c remained largely the same after MM2 and after Gaussian optimisation. However, the structure of 4c had changed after Gaussian optimisation. The MM2 optimised structure of 4c was as expected, but after Gaussian optimisation, the N-O bond had disappeared. There was also a noticeable difference between the structure of Gaussian optimised 4c when viewed in the Gaussview program compared to when viewed in ChemBio3D. In Gaussview, the N and O atoms are not attached to H atoms, whereas in ChemBio3D (shown immediately above) both the N and O atoms are attached to H atoms.

It was thought that the change in structure of molecule 4c upon Gaussian optimisation was evidence that the MM2 and Gaussian DFT/mpw1pw91 optimisation methods did not suit 4c very well, therefore it was advised that 4c should be optimised by another method.

The 4c molecule was drawn into ChemBio3D once again, but this time it was optimised only by MOPAC/RM1 method. This gave the following structure:

It can be seen that molecule 4c optimised by the MOPAC method gave the desired structure, as opposed to when it was optimised by the Gaussian method.

Having obtained the desired structures of 3c and 4c after optimisation, both of the Gaussian Checkpoint files were saved, edited for NMR Chemical Shift Calculation, and submitted to SCAN.

The Gaussian Log Files were opened in Gaussview 3 program and the structures were labelled as shown. The NMR data was obtained and is shown below, and compared to the corresponding literature data:

| 13C NMR Chemical Shift for Molecule 3c | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Number | Calculated Shift/ppm | Literature Shift/ppm[6] | Difference/ppm |

| 3 | 66.9131 | 68.4 | 1.4869 |

| 1 | 61.2448 | 61.1 | -0.1448 |

| 7 | 50.8187 | 55.1 | 4.2813 |

| 4 | 45.2047 | 41.1 | -4.1047 |

| 6 | 30.8354 | 29.1 | -1.7354 |

| 8 | 22.548 | 24.4 | 1.852 |

| 9 | 20.0084 | 23.5 | 3.4916 |

| 11 | 16.8003 | 13.4 | -3.4003 |

| 10 | 11.1863 | 9.3 | -1.8863 |

Above shows the NMR shifts calculated for molecule 3c optimised by Gaussian. These were reasonably close to those reported in literature[6], which indicates that this Gaussian NMR prediction method worked reasonably well with this molecule.

| 13C NMR Chemical Shift for Gaussian optimised Molecule 4c | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Number | Calculated Shift/ppm | Literature Shift/ppm[6] | Difference/ppm |

| 3 | 72.9142 | 72.9 | -0.0142 |

| 1 | 62.6715 | 62.4 | -0.2715 |

| 7 | 49.2629 | 50.1 | 0.8371 |

| 4 | 32.5676 | 37.4 | 4.8324 |

| 6 | 14.8329 | 12.7 | -2.1329 |

| 9 | 11.4005 | 8.9 | -2.5005 |

| 8 | 20.7023 | N/A | N/A |

| 11 | 13.6288 | N/A | N/A |

| 13 | 10.0146 | N/A | N/A |

Above shows the calculated NMR shifts of the molecule 4c optimised by a Gaussian/DFT method. Despite the structure of the molecule being slightly changed after optimisation (the N-O bond disappeared), the calculated values seem to match reasonably well with the literature. There was also the worry that when the structure of the optimised molecule was opened up in ChemBio3D, the N and O atoms both seemed to be attached to H atoms, but since the calculated data indicates that the correct molecule has been obtained after optimisation, there might simply be a problem with the ChemBio3D program in reading the optimised files.

| 13C NMR Chemical Shift for Gaussian optimised Molecule 4c | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Number | Calculated Shift/ppm | Literature Shift/ppm[6] | Difference/ppm |

| 8 | 62.0081 | 72.9 | 10.8919 |

| 5 | 53.3703 | 62.4 | 9.0297 |

| 3 | 41.0192 | 50.1 | 9.0808 |

| 9 | 14.3248 | 37.4 | 23.0752 |

| 6 | 14.0597 | 12.7 | -1.3597 |

| 2 | 11.6948 | 8.9 | -2.7948 |

| 1 | 7.82933 | N/A | N/A |

| 10 | 2.26181 | N/A | N/A |

| 11 | 1.73157 | N/A | N/A |

Above shows the calculated NMR shifts for the molecule 4c optimised only by the MOPAC/RM1 method. The structure of the optimised molecule was as desired, therefore it is strange that the differences between the calculated and literature values are so large. It is known that deviations of more than 5ppm are indicative that the wrong conformation has been obtained, therefore it can be concluded that using only the MOPAC/RM1 method to optimise the molecule was not sufficient to give the lowest energy conformation.

In order to spectroscopically differentiate between the two isomers 3c and 4c, the NMR spectra of both must first of all be measured to be sufficiently different in order to be told apart. This is true for 3c and 4c as the the literature shifts of C-6 (29.1ppm vs 12.7ppm) and C-9 (23.5ppm vs 8.9ppm) are very different in both isomers (3c vs 4c), and in molecule 4c the subsequent peaks are not even observed.

The expected difference is observed in the calculated values, where the C-6 (30.8354ppm vs 14.8329ppm) and C-9 (20.0084ppm vs 11.4005ppm) resonances are seen to be very different between the two isomers (3c vs 4c).

Therefore it can be concluded that this method of 13C NMR prediction does allow for isomers to be distinguished from one another, given that the expected NMR spectrum is already known to be distinguishable.

However it should be noted that despite the last three peaks in molecule 4c being unobservable in actual fact (ie. literature), the NMR prediction calculation was not able to predict this. One of the shortfalls of this NMR prediction method is therefore the inability to be able to predict the intensity of a certain resonance peak, which can sometimes be very indicative of a certain molecule or a specific functional group.

3J H-H Coupling

Although 13C NMR spectra of molecules can be predicted using the above method, the same cannot be done for 1H NMR to the same degree of accuracy. However, the 3J H-H coupling values can be predicted with reasonable accuracy using a method which is based on the Karplus equation, which relates the dihedral angle to the 3J coupling constant.

Upon close study of the molecules3c and 4c it was decided that analysis of 3J H-H coupling would not help with distinguishing between the two isomers because the regioisomerism that they exhibit did not dramatically change any of the dihedral angles in the molecule, and therefore no significant differences would be expected between the isomers, and this would not enable the two isomers to be distinguished from one another.

IR analysis

The IR vibrational normal modes of molecules 3c and 4c were calculated by creating a new Gaussian input file, after only MM2 optimisation, and editing the input file to carry out both geometry optimisation and vibrational frequency calculations.

After the optimisation and vibrational calculations, the molecules had the following structures:

The important vibrations which were obtained from the calculcations are shown below for both molecules:

| Calculated Frequency | Literature Frequency[6] | Vibration | Relative Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3109.71 | 3100 | C-H asymmetric stretch | 50.3949 |

| 2993.95 | 3010 | C-H asymmetric stretch | 46.2988 |

| 2942.23 | 2960 | C-H stretch | 40.1849 |

| N/A | 2870 | C-H stretch | N/A |

| N/A | 2840 | C-H stretch | N/A |

| 1464.08 | 1460 | C-H in-plane bend | 1.8378 |

| 1374.35 | 1350 | C-C stretch, C-H asymmetric stretch | 22.2508 |

| 1253.45 | 1235 | in-plane bend | 26.0775 |

| 1134.92 | 1120 | in-plane bend, C-N stretch | 8.5515 |

| 1006.83 | 1005 | in-plane bend, N-O stretch | 14.7782 |

| Calculated Frequency | Literature Frequency[6] | Vibration | Relative Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3104.32 | 3100 | C-H asymmetric stretch | 67.516 |

| 2997.79 | 3010 | C-H asymmetric stretch | 83.3843 |

| N/A | 2960 | C-H stretch | N/A |

| N/A | 2870 | C-H stretch | N/A |

| N/A | 2840 | C-H stretch | N/A |

| 1483.07 | 1460 | C-H in-plane bend | 2.1762 |

| 1340.39 | 1350 | C-H in-plane bend | 5.985 |

| 1234.51 | 1235 | C-H in-plane bend | 6.2507 |

| 1096 | 1120 | C-C stretch, C-N stretch | 15.659 |

| 1017.54 | 1005 | C-H in-plane bend, N-O stretch | 3.3068 |

Since both isomers 3c and 4c generally have the same bonds and the same functional groups, the expected IR peaks would be the same in both molecules. In fact, the literature gave only one IR analysis for both molecules on this basis.

The calculated vibrationakl frequencies were therefore very similar in both molecules, and the important peaks were assigned to the same type of vibration.

Therefore, IR would not be a good method to distinguish between the two isomers.

Conclusion

This mini-project considered three spectroscopic methods of analytically differentiating between two isomers (13C NMR, 3J H-H coupling and IR) but for the particular isomers under study, only the 13C NMR analysis would allow the isomers to be differentiated because the two isomers do not show significant differences in their dihedral angles, and the functional groups present in both isomers are the same, therefore giving rise to the same IR peaks.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 A. G. Shultz, L. Flood and J. P. Springer, J. Org. Chemistry, 1986, 51, 838 DOI:10.1021/jo00356a016

- ↑ S. Leleu, C.; Papamicael, F. Marsais, G. Dupas, V.; Levacher, Vincent, Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, 2004, 15, 3919-3928DOI:10.1016/j.tetasy.2004.11.004

- ↑ W.F. Maier, P.v.R. Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103, pp 1891-1900

- ↑ B. Halton, R. Boese and H. S. Rzepa, J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 2,, 1992, 447 DOI:10.1039/P29920000447

- ↑ B. Halton, R. Boese, H.S. Rzepa., J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 2, 1992, 447. DOI:10.1039/P29920000447

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 A. Brandi, S. Garro, A. Guarna, A. Goti, F. Cordero, F. D. Sarlo, J. Org. Chem., 1988, 53, pp 2430-2434 DOI:10.1021/jo00246a008