Rep:Modaxg3

Third Year Computational Laboratory - Module 3: Transition States and Reactivity

Cope Rearrangement

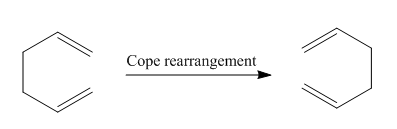

The cope rearrangement is a [3,3]-sigmatropic reaction, which proceeds via a concerted mechanism where one sigma bond is formed and one is broken. Conjugated sysmtems such as 1,5-hexadiene can undergo Cope reaarangement. In this reaction, a thermal pericyclic 1,5 diene forms a regioisomeric diene via a high energy transition state, which suggests that thermal energy is required for the isomerisation[1]. The reaction scheme is shown as follows:

Optimisation of 1,5-hexadiene using HF/3-21G

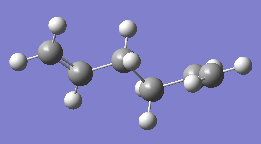

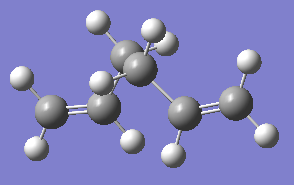

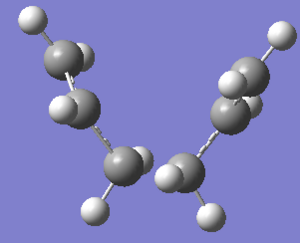

The anti conformation of the 1,5 diene has the bonds between the alkene groups and the central two carbons antiperiplanar to each other, i.e. a dihedral angle of 180 degrees. Usually molecules prefer to adopt antiperiplanar conformation compared to gauche, as the bulky groups can be kept farthest away from each other to allow for reducing steric effect. Three different anti-conformers were drawn in Gaussivew and optimised using Hartree Fock method and basis set of 3-21G. The optimised conformers with total energy and poing group symmetry are shown in the table below:

| Molecule no. | Structure | Point Group | Energy/Hartrees |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Ci | -231.69253 | |

|

C2 | -231.69260 | |

|

C2h | -231.69539 |

The above conformers can be identified from the table in Appendix 1, however the labels for anti-1, anti-2 and anti-3 are different from the reference table. The anti-1 conformer above matches anti-2 in the reference, anti-2 matches anti-1 and anti-3 is consistent with the reference.

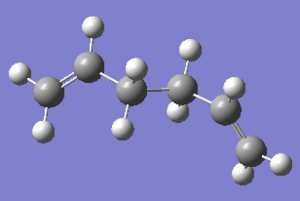

The gauche conformers were also optimised under HF/3-21G level of theory. The results are shown in the table below:

| Molecule no. | Structure | Point Group | Energy/Hartrees |

|---|---|---|---|

|

C2 | -231.69167 | |

|

C1 | -231.69266 | |

|

C2 | -231.69153 |

Comparing the energies of all conformers, the anti-3 with C2h symmetry has the lowest energy (most negative) of all. However, the literatureCite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title indicates the gauche-2 conformer is the most stable one due to stereoelectronic reasons: the donation of electron density from the πC=C orbital of the C=C bond into the σ*C-H antibonding orbital of the adjacent vinyl proton is strongly favoured, and the interaction between the hybridised sp3 and sp2 carbons are effectively minimised.

Comparison of Optimisation Result Between HF/3-21G and B3LYP/6-31G(d)

Since the 3-21G is a low-level basis set, the optimised anti-conformer was re-optimised using DFT/B3LYP/6-31G(d) to find a structure with lower energy and higher accuracy. The resulted strctures with energies, bond lengths and bond angles are shown in the table below:

The change in bond lengths are subtle after optimising with B3LYP/6-31G(d). The dihedral angles, however, changed significantly from 114.6 to 118.6. The energy was lowered by ca. 3 Hartrees as well. The drawback of using the more accurate basis set is longer CPU running time.

Comparison of Energies in Thermochemistry

The thermo properties of anti 1,5-hexadiene at B3LYP/6-31G(d) level of optimisation was shown in the following table.

| Energies | At 289.15 K | At 0 K |

|---|---|---|

| Sum of Electronic and Zero-point Energies, i.e. E = Eelec + ZPE / a.u. | -234.46921 | -234.46626 |

| Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies at 298.15K and 1atm, i.e. E = E+ Evib + Erot + Etrans / a.u. | -234.46186 | -234.46068 |

| Sum of Electronic and Thermal Enthalpies, i.e. H = E + RT / a.u. | -234.46091 | -234.45973 |

| Sum of Electronic and Thermal Free Energies, i.e. G = H - TS / a.u. | -234.50078 | -234.49551 |

| log file | DOI:10042/to-2706 | DOI:10042/to-2705 |

The energies are observed to be slightly higher at 0K, which means the anti diene is less thermodynamically stable at that temperature compared to 298.15K. This is because more energy is required to achieve the translation, rotation and vibration of the molecule at 0K.

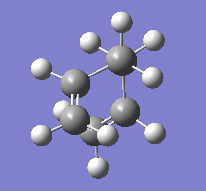

Optimisation of Chair and Boat Transition Structure

Various Approaches for Optimisation of Chair Transition Structure

A allyl fragment C3H5, which is half of the transition strucutre, was drawn in Gaussview and optimised under HF/3-21G level of theory, which yielded a planar fragment with electron density delocalised on the fragment. Two of this fragment were combined to give a trial structure with the distance between the terminal ends of the fragment approximately 2.2 angstroms apart from each other. The guess structure was optimised using a direct Berny TS approach and a frozen coordinate ModRedundant Minimisation followed by Berny TS optimisation. The results are shown in the table below:

| Approach | Optimistion to TS (Berny) | ModRedundant Coordinate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bond forming/breaking length (Å) | 2.020 | 2.020 | ||||||

| Electronic Energies (Hartrees) | -231.61932247 | -231.61932219 | ||||||

| Structures |

|

| ||||||

| Imaginary Frequency (cm-1) | 817.93 | 817.73 | ||||||

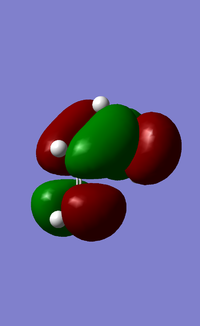

| Vibrational image |  |

| ||||||

| Log file link | DOI:10042/to-5561 | DOI:10042/to-5564 |

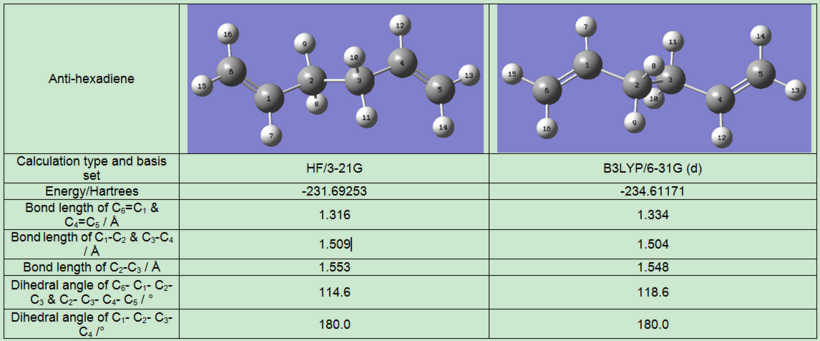

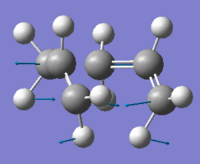

From above table, it can be seen that the structures optimised using two approaches furnished similar results, in terms of energy, imaginary frequencies and bond forming/breaking lengths. The vibrational animation image shows the bond forming and bond breaking happened simultaneously (vibrations indicated by blue vector arrows), which is consistent with the concerted mechanism in Cope rearrangement.

For this simple molecule, the direct TS(Berny) optimisation gives reasonable result, which is similar to the data obtained from redundant coordinate approach. In this case, the second method does not necessarily have to be carried out. It can however be applied to a more complicated system where TS(Berny) is insufficient, i.e. it cannot optimise the guess structure.

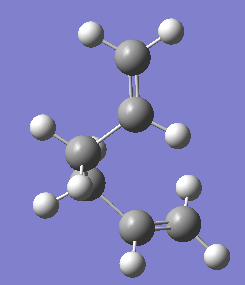

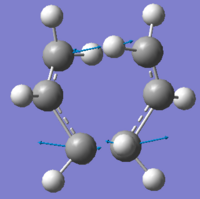

Optimisation of Boat Transition Structure using QST2 Approach

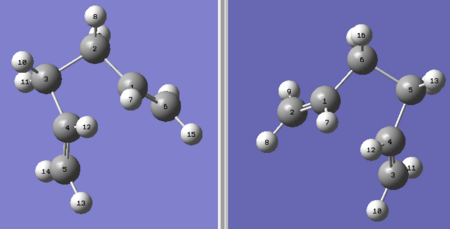

The boat transition structure was optimised using QST2 approach, where both the reactant and the product were involved in the calculation and the structure of the lowest energy was generated. The numbering of all atoms is a key step in preparing the reactant and product to be optimised. The most efficient way (for me) of doing this was to re-number all carbon atoms first and then match the hydrogen atoms accordingly, shown as the following:

This calculation failed although the geometry and the numbering were correct, because Gaussian failed to take the possibility of rotation around the central bonds into account. Upon modifying the dihedral angle of the central four carbons to 0 degree and the central bond angle to 100 degrees (see image on the right), the resulted structures were optimised again and it worked. The results were as follows:

| Approach | QST2 optimisation of boat conformation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bond forming/breaking length (Å) | 2.140 | |||

| Electronic Energies (Hartrees) | -231.60280 | |||

| Structures |

| |||

| Imaginary Frequency (cm-1) | 840.04 | |||

| Vibrational image |  | |||

| Log file link | DOI:10042/to-5573 |

From above table, one imaginary frequency was observed at -840.04 cm-1, which indicates the transition structure. As can be seen from the vibrational image, two vectors on the same ends from each fragment move towards each other and the other two vectors on the other ends move away from each other simultaneously. This is a consistent result with the mechanism of Cope rearrangement, where the bond formation and bond breaking are in a concerted fashion.

QST2 method is not as straightforward as the TS(Berny) optimisation in terms of usage, because the numbering process is tedious, especially for larger molecules.

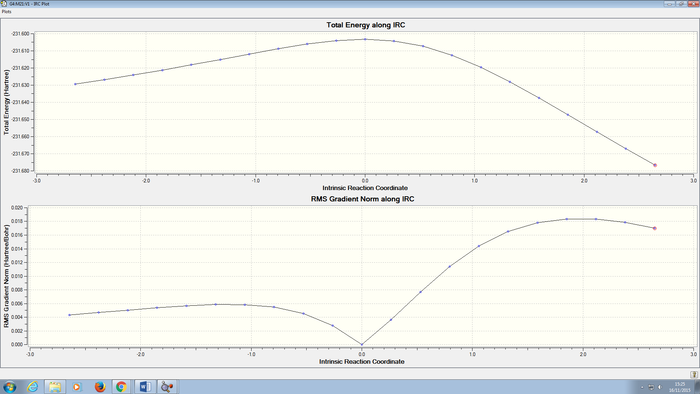

Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate Calculation for Chair Conformation

The intrinsic reaction coordinate calculation of the chair conformation was carried out on DFT-B3LYP/6-31G(d) level of theory. The aim of doing the calculation is to predict the optimised geometry of the product, or to confirm the success of minimisation. Because only analysing the transition state geometries of the chair and boat conformations is not possible to predict the original conformations of reactants and products. The Cope rearrangement has a symmetrical energy plot, i.e. the geometry of the product is the same as that of reactant.

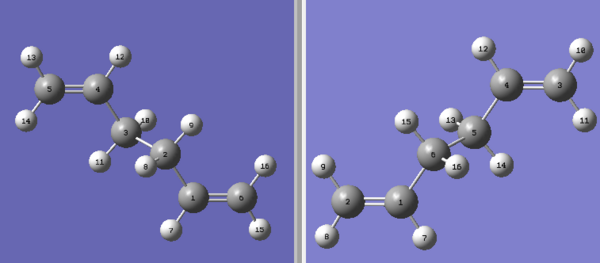

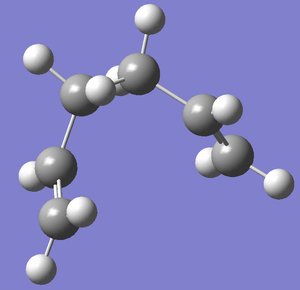

The IRC calculation consistently optimises the geometry of the transition state at every step, and predicts the next geometry that minimises the energy of the transition structure. The accuracy of calculation depends on how many steps are chosen and how often the force constant is calculated. Two different criteria were tested in this case, a rough one first, in which 50 points were selected and the force constant was only calculated once; and a more accurate one, where 120 points were selected and the force constant was always calculated. The optimised structures and IRC path are shown as the following:

| Calculation settings | 50 points, force constant calculated once | 120 points, force constant calculated always |

|---|---|---|

| Final Energy / a.u. | -231.61932 | -231.69166 |

| IRC Pathway |  |

|

| Structure |  |

|

| Output file | DOI:10042/to-5578 | DOI:10042/to-5579 |

The first optimisation gives a higher final energy than the more accurate one. This can be seen from the IRC path: in the first plot, the curve seemed to be still on the way decreasing the energy, i.e. the minimum on the potential energy surface was not reached and the optimisation was incomplete; whereas in the second plot, the energy for the second half of the optimisation process yielded similar energies for each single step, which suggested the optimisation was complete and the optimised structures should not be too different from one another. However the more accurate method requires more time to run and is more expensive. The structures look different as well, the final optimised structure corresponds to the Gauche-1 in the first part of the analysis (i.e. Gauche 2 conformer in Appendix 1.

Thermochemistry of Chair and Boat Transition Structures

opt=CalcFC was added in the additional keywords in the Gaussian calculation when optimising the boat transition structure. It calculates the force constant at the first step. Various thermal properties of chair and boat transition structures were calculated, shown as the following:

The output files for the activation energy of chair and boat transition structures can be found in DOI:10042/to-5582 and DOI:10042/to-5583

| Energy and Temperature | Chair TS at 0 K | Chair TS at 298.15 K | Boat TS at 0 K | Boat TS at 295.15 K |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Energy / a.u. | -234.55698 | -234.55698 | -234.54309 | -234.54309 |

| Sum of Electronic and Zero-Point Energies / a.u. | -234.41449 | -234.41493 | -234.40190 | -234.40234 |

| Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies / a.u. | -234.40858 | -234.40901 | -234.39558 | -234.39601 |

| Sum of Electronic and Thermal Enthalpies / a.u. | -234.40763 | -234.40807 | -234.39464 | -234.39506 |

| Sum of Electronic and Thermal Free Energies / a.u. | -234.44336 | -234.44382 | -234.43130 | -234.43175 |

| Activation Energy / a.u. | 0.05701 | 0.05655 | 0.10573 | 0.06862 |

| Activation Energy / kcal mol-1 | 43.70 | 36.45 | 56.59 | 43.33 |

| Experimental data / kcal mol-1 | 33.5±0.5 | - | 44.7±2.0 | - |

Comparing to the results obtained previously using HF/3-21G level of theory, both conformations were optimised to lower energies, as DFT-B3LYP/6-31G(d) is a higher level optimisation, which modifies the C-C bond lengths of forming and breaking and reduces the energy.

The activation energy is obtained by taking the difference between the sum of electronic energy and thermal free energy within chair/boat and anti-1 conformer (or anti-2 in Appendix 1). The activation energies of both conformers deviate significantly from experiment. This means that the optimised transition structures were not effectively the ones with the lowest energy.

At 0K and 298.15K, the chair conformation has lower activation energy than boat,which suggests that the chair transition state is favoured over the boat. Therefore in the Cope rearrangement, the transition state is chair conformation with lower activation energy.

Diels Alder Cycloaddition

Diels Alder reaction is cycloaddition between conjugated diene system and a dienophile, it is denoted as [4+2] where the number 4 and 2 represent the number of electrons involved in the cycloaddition. The reaction scheme and mechanism are shown below:

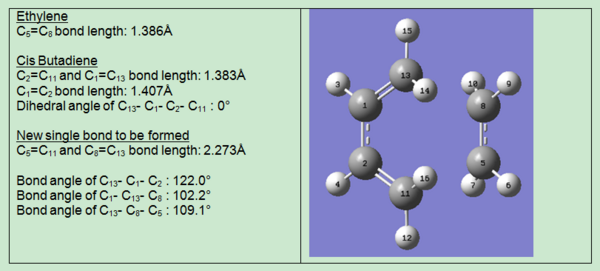

Optimisation of Cis-Butadiene

The cis butadiene was optimised on DFT-B3LYP/6-31G(d) level of theory, the results of which are shown below:

| Electronic Energy (a.u.) | -155.98594 | |||

| Terminal C=C Bond Length (Å) | 1.340 | |||

| Internal C-C Bond Length (Å) | 1.471 | |||

| Structure |

|

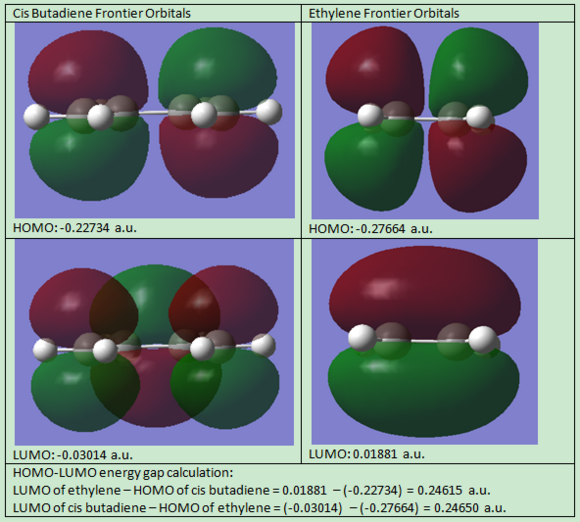

Frontier Orbitals Analysis of Cis-Butadiene

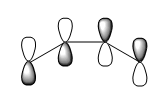

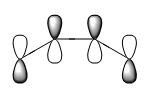

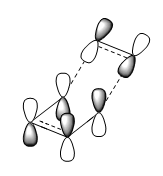

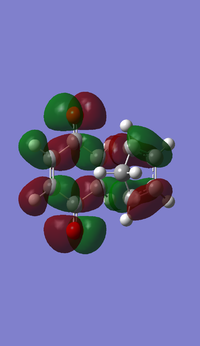

The frotier orbitals (HOMO and LUMO region) of cis butadiene were obtained from the checkpoint file. In the meantime, the orbitals predicted from Linear Combination Molecular Orbital method are also shown below:

| Methods | HOMO | LUMO |

|---|---|---|

| LCAO HOMO/LUMO Prediction |  |

|

| DFT B3LYP MO Prediction |  |

|

| Orbital Energy (a.u.) | -0.22734 | -0.03014 |

| Symmetry | Antisymmetrical | Symmetrical |

If a vertical line is drawn at the mid point of the orbital, the HOMO is antisymmetric about the plane of symmetry (vertical lien); and the LUMO is symmetric. The symmetry is an essential part in predicting the feasibility of a reaction, as orbital shapes determine whether or not the overlap/interaction exists; it also has an effect on the stereochemistry of the products.

Optimisation of Transition Structures

With both optimised reactants, the diene and dienophile in hand, the transition structure can be then optimised in a sequence fashion: the guess transition structure was optimised uisng Semi-empirical/AM1 (low level of theory) in combination of freezing the distance of C-C bond to be formed to 2.1 on the ModReduntant coordinate; second optimisation was via TS(Berny) and Semi-empirical/AM1 method to generate the unfrozen bond forming distance; at the final stage, both optimisation and frequency calculations were brought to a higher level, DFT-B3LYP/6-31G(d). The results were shown as the following:

| Methods | Semi-empirical/AM1 | DFT-B3LYP/6-31G(d) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure |

|

| ||||||

| Electronic Energy (a.u.) | 0.11165 | -234.54340 | ||||||

| Imaginary Frequency (cm-1) | -957.2 | -525.0 | ||||||

| Vibrational Mode |  |

| ||||||

| C-C Bond Forming Length (Å) | 2.119 | 2.272 | ||||||

| Log file link | DOI:10042/to-5586 | DOI:10042/to-5585 |

QST2 method was not utilised here due to tedious numbering procedure.

It can be noted that the difference between the energies optimised from both methods is significant, however there is no need to worry about this huge difference as the semi-empirical method uses a different way in reporting energy compared to DFT method.

One imaginary frequency was observed in both methods, however they are very different again due to the fact stated earlier. Nonetheless this negative frequency confirms a transition structure was found. Looking at the vibrational image at that frequency, it shows the bond breaking and bond forming process indicated by the blue vectors. This result is consistent with the Diels Alder concerted cycloaddition mechanism, where bond breaking and bond forming are simultaneously.

The bond length of C-C to be formed is larger in DFT method compared to Semi-empirical bond length. This observation suggests the slope of the potential energy towards the end of optimisation is less steep, which results in a reduced imaginary frequency in wavenumbers.

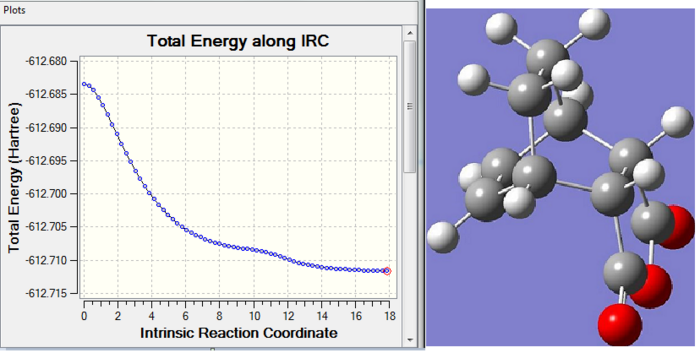

Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate of Transition State

An intrinsic reaction coordinate method can be applied here to confirm that the transition structure was properly and completely optimised. 200 points were selected and the force constant was calculated always. This calculation was carried out at B3LYP/6-31G(d) level of theory. The IRC path can be obtained in DOI:10042/to-5592 . The IRC pathway and the final optimised structure are shown below:

From the energy vs IRC plot, the energy first decreases fast and then gradually converged to a minimum and stabilised at that energy. This suggests the optimisation was successful and completed. Looking at the image of the final optimised structure, it is very similar to the one obtained above.

Activation Energy of the Reaction

The activation energy is given by the difference between the total free energy of the reactants (-234.48561 a.u.) and that of the transition structure (-234.43289 a.u.). Therefore the activation energy was calculated to be 0.0527 a.u. (or 138.5 kJ mol-1). This result was in good agreement with the experimental value (115±5 kJ mol-1) in the literature[2].

Therefore from the energetical point of view, the reaction is energetically-allowed due to the small activation energy, which is strongly favoured in the kinetically controlled reaction, i.e. the activation barrier is small and is easier to be overcome.

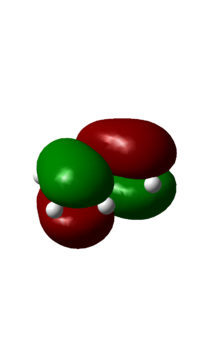

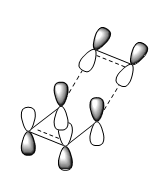

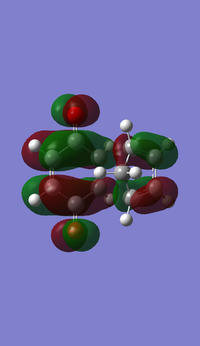

Frontier Orbitals of Transition Structure

The frontier (HOMO and LUMO) orbitals were calculated on B3LYP/6-31G(d) level of theory and LCAO was also predicted. The results are shown in the table below:

| Methods | HOMO | LUMO |

|---|---|---|

| LCAO HOMO/LUMO Prediction |  |

|

| DFT B3LYP MO Prediction |  |

|

| Orbital Energy (a.u.) | -0.22103 | -0.00867 |

| Symmetry | Antisymmetrical | Symmetrical |

Again if a line is drawn vertically dividing from the mid point of the C-C single bond in cis-butadiene to represent the plane of symmetry, the HOMO is antisymmetric with respect to this plane and the LUMO is symmetric.

The HOMO of the transition structure is made from antisymmetrical HOMO of cis butadiene and the antisymmetrical LUMO of ethene. This retention of symmetry is symmetry-allowed according to the rules in conservation of orbital symmetry[3], which states that the transition of MOs from reactants to the products via a concerted fashion does not change the orbital symmetry.

The orbitals involved represent the nature of Diels Alder cycloaddition, where 6 electrons are involved in the Huckel transition state with suprafacial components under thermal conditions. The diene (cis-butadiene) acts as the electron rich species, with its HOMO interacting with the LUMO of the dienophile (ethene), which is the electron poor species and is ready to accept electron density from the incoming HOMO. The formation of new bond occurs on the same face of the pi system in butadiene and also the same face of pi system in ethene, yielding suprafacial TS. This is therefore allowed in the pericyclic selection rule[4].

The energy gap between the HOMO of butadiene and LUMO of ethene was calculated in the table above, and the calculation was also done the other way round, i.e. the energy gap between the HOMO of ethene and LUMO of butadiene. It can be seen that the former has a smaller energy than the later. This indicates that the energy gap between the HOMO of cis butadiene and the LUMO of the ethene is small, therefore the interaction is strong and the energy splitting is large. This phenomenon is due to a favourable orbital overlap attributed to the conserved orbital symmetry discussed above.

Geometry of Transition Structure

The geometry of the transition structure was characterised including bond lengths, bond angles and dihedral angles. The results are shown in the table below:

The typical sp3-sp3 C-C bond length is 1.54Å and the typical sp2-sp2 C-C bond length is 1.47Å; the van de waals radius of carbon is 1.70Å[5]. The C-C bond to be formed in the transition structure is 2.12Å, which is significantly different from the typical sp3 C-C bond length. However it is within twice the van der waals radius of carbon. Therefore it is concluded that the σ C-C bond formation was proceeding, but was not completely formed yet. When the bond formation was completed, the bond length is expected to be closer to the typical sp3-sp3 C-C bond length.

Longer C-C bond length suggests the angle resulted from orientation of the cis-butadiene with respect to ethene yields a stronger HOMO-LUMO interaction for the reaction to proceed.

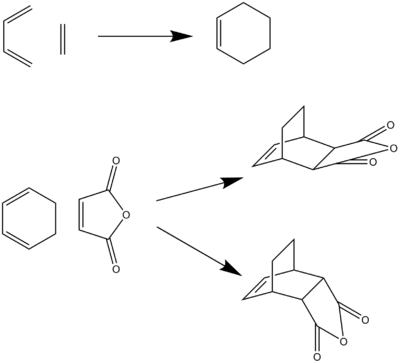

Cycloaddition of Cyclohexa-1,3-diene and Maleic Anhydride

Another Diels Alder reaction between cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride is studied in this part. However compared to the previous Diels Alder cycloaddition, this reaction gives two products, a mixture of endo and exo diastereomers. They are formed by diene attacking from different direction on the maleic anhydride. The endo isomer is expected to be the major product, as most of the Diels Alder reactions are kinetically controlled, and the kinetic product will be formed preferentially. This will be discussed in more details later.

The reaction scheme is shown as follows:

Optimisation of Reactants

Optimisation of cyclohexa-1,3-diene

| Electronic Energy (a.u.) | -233.41894 | |||

| Structure |

| |||

| Output file link | DOI:10042/to-5594 |

The optimisation was done on B3LYP/6-31G(d) level of theory and structure of cyclohexa-1,3-diene is shown above. It can be seen that the diene part of the 6-membered ring is flat, as in an aromatic system, the unsaturated unit is slightly above (or below depending on the orientation of viewing the molecule) the diene plane.

Frontier Orbitals of cyclohexa-1,3-diene

| Properites | HOMO | LUMO |

|---|---|---|

| DFT B3LYP MO Prediction |  |

|

| Orbital Energy (a.u.) | -0.20552 | -0.01711 |

| Symmetry (with respect to the plane perpendicular to the ring) | Antisymmetrical | Symmetrical |

The HOMO and LUMO were obtained from the checkpoint file. The HOMO is antisymmetrical with respect to the plane perpendicular to the ring, and the LUMO is symmetrical.

Interestingly, the LUMO is expected to have a positive orbital energy. However it is negative. This may be resulted from the limitation of the method.

Optimisation of Maleic Anhydride

| Electronic Energy (a.u.) | -379.28954 | |||

| Structure |

| |||

| Output file link | DOI:10042/to-5595 |

The calculation was performed on the same level of theory as previously to maintain the consistency of the results. The maleic anhydride is flat with respect to the plane of the ring.

Frontier Orbitals of Maleic Anhydride

| Properites | HOMO | LUMO |

|---|---|---|

| DFT B3LYP MO Prediction |  |

|

| Orbital Energy (a.u.) | -0.29929 | -0.11713 |

| Symmetry (with respect to the plane perpendicular to the ring) | Antisymmetrical | Antisymmetrical |

Again the LUMO orbital energy is calculated to be negative due to the limitation of the DFT method, though it was expected to be positive.

Both HOMO and LUMO are antisymmetrical with respect to the plane perpendicular to the ring, because the phases are inverted everywhere.

Optimisation of Transition Structure

The transition structure was optimised on B3LYP/6-31G(d) level of theory to retain the consistency with previous calculations of reactants. The results are shown in the following table:

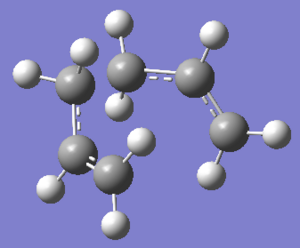

| Properties for product mixture | Endo TS | Exo TS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bond forming length (Å) | 2.268 | 2.291 | ||||||

| Electronic Energies (Hartrees) | -612.68340 | -612.67931 | ||||||

| Structures |

|

| ||||||

| Imaginary Frequency (cm-1) | -447 | -448 | ||||||

| Vibrational image |  |

| ||||||

| Log file link | DOI:10042/to-5598 | DOI:10042/to-5599 |

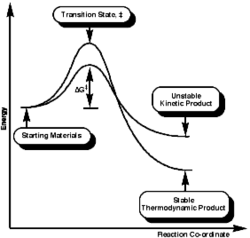

Comparing the energies of the two TS, the endo TS was of lower energy (more negative) than the exo TS. This observation differs from the products energy in most of the Diels Alder reactions, where the exo products are lower in energy compared to the endo product. In most of the Diels Alder cycloaddition, the thermodynamic TS (exo) has higher activation energy and lower final energy, therefore is stable; whereas the kinetic TS (endo) has lower activation barrier and is easier to form, but has higher final energy for the product, and is therefore less stable compared to the exo product. This is illustrated in the energy diagram on the right.

The inverse of stability of endo and exo can be explained using secondary orbital knowledge, which states that the secondary orbital interactions in the endo transition state stabilises the whole molecule. This will be discussed in more detail later.

Both diastereomers have a negative imaginary frequency, which means the optimised transition structures were found. Their frequencies are very similar, therefore it can be deduced that they both represent the same vibrational mode. Looking at the vibrational image at that frequency, it shows the bond breaking and bond forming process indicated by the blue vectors. This result is consistent with the Diels Alder concerted cycloaddition mechanism, where bond breaking and bond forming are simultaneously.

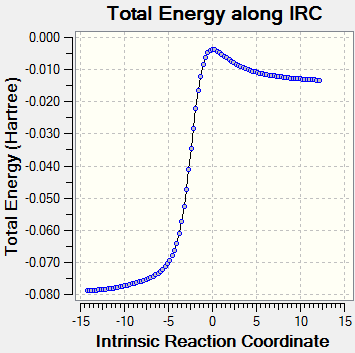

Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate

An intrinsic reaction coordinate method can be applied here to confirm that the transition structures of endo and exo were properly and completely optimised. 200 points were selected and the force constant was calculated always. The IRC path can be obtained in DOI:10042/to-5604 for endo and DOI:10042/to-5605 for exo. The IRC pathway and the final optimised structures are shown below:

From the energy vs IRC plot, the energy first decreases fast and then gradually converged to a minimum and stabilised at that energy. This suggests the optimisation was successful and completed. Looking at the image of the final optimised structure, the endo TS has its two hydrogens on the anhydride ring pointing upwards and the anhydride functionality (the O=C-O-C=O fragment) pointing downwards; the exo TS has its two hydrogens on the anhydride ring pointing downwards and the anhydride functionality pointing upwards.

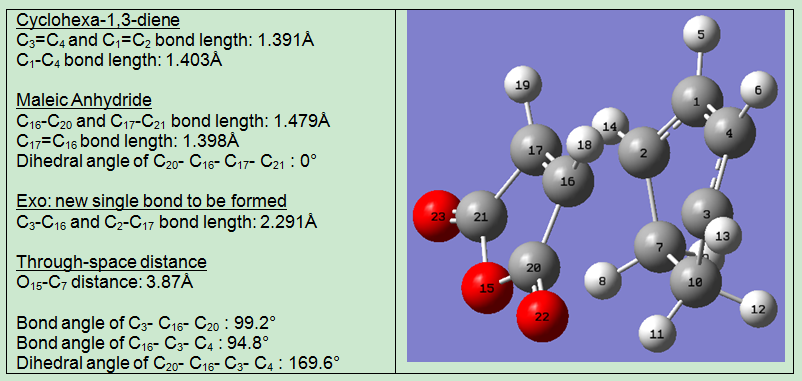

Geometry of Transition Structures

The bond lengths of C-C bond to be formed are similar for endo and exo product. The C-C bond forming length is slightly larger for the exo product. Longer bond length means the newly formed bond is less stable, which is consistent with the the previous energy calculation which indicates exo is the less stable product.

Looking at the through-space (nonbonding) distances, in the endo product, the distance from the C=C double bond to the central oxygen in the O=C-O-C=O unit on the anhydride is 2.88 angstroms; whereas in the exo product, the distance from the -CH2-CH2- unit to the O=C-O-C=O unit on the anhydride is 3.87 angstroms, i.e.the through space distance is shorter for the endo product. This suggests the exo product is subject to more steric repulsion resulted from the anhydride functionality (the O=C-O-C=O unit) and the C=C bond. These observation suggests the endo product is less thermodynamically stable. However the computed results have shown the endo product is actually more stable, this is again due to the secondary orbital interactions and will be discussed shortly.

The dihedral angle in the bond formation region differ significantly due to the orientation of the incoming anhydride, i.e. the angle is dependent upon whether the anhydride attacks from bottom or top face.

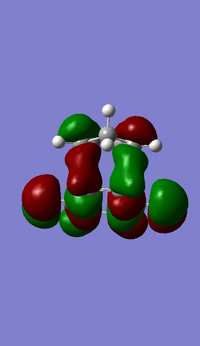

Frontier Orbitals of Transition Strucutres

The frontier orbitals (HOMO and LUMO) are calculated for both products, with their symmetry assigned, as shown below:

| Endo TS Orbitals | HOMO | LUMO |

|---|---|---|

| DFT B3LYP MO Prediction |  |

|

| Orbital Energy (a.u.) | -0.24230 | -0.06775 |

| Symmetry | Antisymmetrical | Antisymmetrical |

| Exo TS Orbitals | HOMO | LUMO |

|---|---|---|

| DFT B3LYP MO Prediction |  |

|

| Orbital Energy (a.u.) | -0.24215 | -0.07840 |

| Symmetry | Antisymmetrical | Antisymmetrical |

The HOMO and LUMO for both TS are antisymmetrical because the phases are inverted everywhere. The orbital energies for LUMO in both TS show negative values again using the DFT method.

The HOMO of the transition structures for both endo and exo is made from the antisymmetrical HOMO of cyclo-1,3-hexadiene and the antisymmetrical LUMO of the maleic anhydride, because its HOMO-LUMO energy gap (0.08839 a.u.) is much smaller than the energy gap between HOMO of the anhydride and LUMO of the diene (0.28218 a.u.). Smaller energy gap means the HOMO and LUMO are closer in energy, and therefore the interactions are stronger and the bonding will be stabilised to a larger extent.

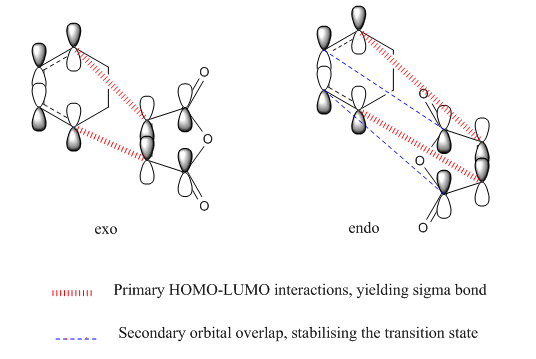

Secondary Orbital Analysis

Both primary and secondary orbital interactions[7] of the transition states for endo and primary orbitals for exo were shown above. The secondary orbital interactions only occur to the endo transition state, and therefore stabilise it as mentioned earlier.

As illustrated from the diagram above, the secondary orbital takes place at the central conjugated diene carbon, interacting with the carbonyl carbon in the anhydride functionality, due to in-space vicinity of the two carbons. Recalling from the molecular orbitals of the transition structures shown earlier, the orbital of the central carbon in the conjugated π-system in the diene and the carbon of the π*C=O orbital have the same phase, therefore some interactions do exist.

In endo TS, it is observed that the nodal plane extends to the remaining system because of the interactions between the carbonyl group and the oxygen on the anhydride functional group. In contrast, this interaction is not detected in the exo transition state due probably to a smaller lobe on the oxygen of the anhydride such that no extension of nodal plane to the remaining system is possible.

The above explanation of the stereoelectronics of this particular Diels Alder reaction yield the conclusion that the endo product is the major product and the cycloaddition between cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride is effectively kinetically controlled.

Conclusion

The transition state of reactions proceeding via a concerted mechanism were studied in this exercise, the reactions include Cope rearrangement and two different Diels Alder cycloadditions. Several different optimisation methods for the transition structures were explored, namely TS(Berny) direct optimisation, ModRedundant Coordinate and QST2, the results were compared and the strength and weakness of the methods were evaluated. All reactions were characterised computationally in terms of thermochemistry, intrisic reaction coordinate analysis, frequency analysis and molecular orbital analysis.

Moreover, the transition structures can be studied in a more quantum mecahnical way by means of Gaussian calculations, so that other features, such as the photoinduced pathways in pericyclic reaction, can be explored and therefore allowing more thorough understanding of the nature of the reactions.

Reference

- ↑ R. K. Hill, Comp. Org. Syn., 1991, 5, 785-826.

- ↑ V. Guner, K.S. Khuong, A.G. Leach,, P.S. Lee, M.D. Bartberger, K.N. Houk, J. Phys. Chem. A, 2003, 107, 11445: DOI:10.1021/jp035501w

- ↑ R. Hoffmann, R.B. Woodward, Acc. Chem. Res., 1968, 1, 17: DOI:10.1021/ar50001a003

- ↑ F.C. He, G.V. Pfeiffer, 'A Generalised Selection Rule for Pericyclic Reactions', 1984, Vol. 61, No. 11

- ↑ S. J. Stuart, M. T. Knippenberg, O. Kum and P. S. Krstic, Phys. Scr., 2006, T124, 58 - 64 DOI:10.1088/0031-8949

- ↑ D.A. Widdowson, 'The Chemistry of Nitrogen Compounds', Chap. 4

- ↑ R. Hoffmann, R.B. Woodward, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1965, 87, 4388: DOI:10.1021/ja00947a033