Rep:Mod 1: CouchMA

Structure and Spectroscopy (Molecular Mechanics / Molecular Orbital Theory)

Introduction

Computational methods are now widely used throughout Chemistry as a substitute for having to perform lengthy and often costly synthetic procedures. Models have been designed which can accurately predict chemical structures and molecular orbitals. These can aid chemists to gain an insight into the reactivity and selectivity of a molecule before they have even entered the lab, thus reducing both overhead costs and time constraint issues often encountered during synthetic research.

This module of the 3rd Year Computational Chemistry course looks into the applications of the MM2 molecular mechanics tool, which uses classical approaches like Hooke's Law to minimise the overall energy of the molecule by a simple optimisation of geometry. The module also looks at more sophisticated methods such as MOPAC/PM6 and MOPAC/RM1 to generate approximate molecular orbitals for the molecules.

Computational methods do, like humans, have their limitations. It is often the case that an experienced chemist must first apply their knowledge to the initial construction of the molecule being submitted in order to reduce the likelihood of the computational method reaching a false (or local) minimum as opposed to the true minimum.

Modelling using Molecular Mechanics

Cyclopentadiene Dimers

The Dimerisation of Cyclopentadiene

Cyclopentadiene rapidly dimerises at room temperature via a Diels-Alder reaction, forming Dicyclopentadiene, which can exist in either one of two configurations 1 or 2. It has been shown[1] that the endo Dimer 2 is formed with 100% selectivity over the other exo Dimer 1.

The MM2 molecular mechanics calculation was used to minimise the energy of the dimers, whose outputs are summarised in Table 1. It can be seen by a simple comparison that the exo Dimer 1 is more stable than its endo counterpart Dimer 2, with the majority of the stabilisation of Dimer 1 coming from the torsion energy. This indicates that Dimer 1 is thermodynamically the most stable product of cyclopentadiene dimerisation, which leads us to the question of why Dimer 2 is formed exclusively.

The exclusive formation of the endo dimer is explained by reaction kinetics, as opposed to thermodynamics. Investigation into the transition states of the formations of Dimers 1 and 2 shows that the transition state of endo Dimer 2 is lower in energy than that of Dimer 1. This is due to favourable interactions in the transition state of Dimer 2, caused by the bispericyclic transition structure[2]. This lower energy transition state causes the reaction towards Dimer 2 to proceed much quicker than the reaction which forms Dimer 1, and seeing as the Diels-Alder reaction is effectively irreversible, Dimer 2 is formed exclusively.

|

Table of Calculated Energies using MM2

The Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimers

Endo dicyclopentatiene (Dimer 2) can be hydrogenated across either of its double bonds, giving Dimers 3 and 4. From the energies presented in Table 1, it is apparent that Dimer 4 is much more stable than Dimer 3, indicating that it is easier to hydrogenate the norbornene double bond.

The data actually indicates that it is an unfavourable process to hydrogenate the cyclopentene C=C bond. This is due to an increase in all energies apart from bending energy, whose stabilisation is not great enough to overcome the other destabilising effects.

From the energies calculated, it can be seen that there is a significant decrease in bending energy (~30kJ/mol) caused by the hydrogenation of the norbornene C=C double bond which is a large enough stabilisation to counteract the increase in torsion energy.

Nucleophilic additions to a Pyridinium ring (NAD+ analogue)

Proline Derivative

In this section the reactions of pryridinium rings are studied, focusing on two examples. The first example looks at the reaction of the opticaly active proline derivative NAD1 with methyl magnesium iodide to stereoselectively form the product NAD2. In the second example, molecule NAD3 is reacted with phenyl amine to solely form the product NAD4.

Due to the bug in ChemBio 3D Ultra 12.0 which cannot deal with N+ when applying the MM2 forcefield, MOPAC was also used to minimise the energy and geometry of the molecules in this section.

The lowest energy structure of NAD1 is shown below in the Jmol file, which shows the carbonyl above the plane of the pryridinium ring. Many different initial conformations were tested, in order to assess whether or not the carbonyl could lie below the plane of the pyridinium ring in a low energy conformation, however the 7-membered ring was very rigid and always snapped back to the same conformation where the carbonyl lay above the plane of the ring.This knowledge can be used to explain why the product NAD2 is formed with high stereoselectivity on the chiral carbon. The proposed reaction mechanism shows the addition of a methyl group to the para position of the pryidinium ring which, due to the coordination of magnesium to the carbonyl oxygen, adds to the top face of the ring. It would be useful to include the MeMgI in the calculations, in order to ascertain whether or not the reaction would proceed as predicted, however when doing so the program returns the error message "WARNING! No atom type was assigned to the selected atom!".

Quinoline Derivative

In the second example, NH2Ph is performing a nucleophilic attack on the para position of the pyridinium ring, resulting in the stereoselective generation of the chiral pruduct NAD4.

Analysis of the reactant NAD3 shows that this time the carbonyl group is below the plane of the ring, regardless of which initial configuration was tried. The lowest energy conformation displays an angle significantly below the plane of the pyridinium ring (negative signs have been used to denote angles below the plane of the ring). The knowledge that the the carbonyl oxygen lies below the plane of the ring gives a decent insight into possible mechanistic explanations for stereospecific addition of NH2Ph. In this example, there is not a magnesium atom in the reagent which can coordinate to the oxygen atom. Instead the amine reacts directly - using its lone pair to attack at the para position of the pyridinium ring. Both the amine and the carbonyl oxygen are electron rich, and thus repel one another, meaning that the nucleophile attacs on the top face of the ring, on the opposite side to the carbonyl. This is again confirmed by the new angle of the carbonyl in NAD4, which has shifted to lie even further below the plane of the ring, confirming the repulsion between the two groups.

Stereochemistry and Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

Intermediates 1 and 2 show the same molecule in two different configurations. In intermediate 1, the carbonyl is referred to as pointing "up", and in intermediate 2, the carbonyl is referred to as pointing "down". This type of isomerism is referred to as atropisomerism and occurs when an energy barrier is encountered in the rotation of a single bond.

Both MM2 and MMFF94 methods were used to minimise the energies of the intermediates, giving vastly differing results, as illustrated in Table 4. Care was taken to ensure that the 6-membered ring was always in a chair conformation before begining the minimisation.

It can be seen in Table 4 that the energy of intermediate 2 is lower, irrespective of which method is used to calculate the energies. Simple visual analysis shows that intermediate 1 has a large amount of steric clash beteen the carbonyl group and the methyl groups on the bridgehead, which would give an indication of why this isomer was higher in energy.

| Intermediate 1 | Intermediate 2 | |

| 3D Image | ||

| Total Energy (MM2) | 201.39kJ/mol | 185.21kJ/mol |

| Total Energy (MMFF94) | 295.09kJ/mol | 253.32kJ/mol |

Hyperstability of Alkenes

The alkene bond in intermediates 1 and 2 is surprisingly unreactive, which seems odd when considering that the bond appers to have no reason to be unreactive. This phenomenon is known as a Hyperstable Alkene and refers to an alkene bond which adds more stability to the molecule than its hydrogenated alkane counterpart. This occurrence, reported by Maier and Schleyer[4], is commonly found in molecules where alkenes are positioned adjacent to a bridgehead. It must however be noted that this is only applicable for bridgehead alkenes where the ring size is large enough to accommodate the strain, thus allowing Bredt's Rule to be obeyed.

Modelling Using Semi-empirical Molecular Orbital Theory

Dichlorocarbene is a highly electrophilic species which readily attacks alkenes to form a 3-membered ring across the double bond, as illustrated in the reaction scheme. In the reaction of dichlorocarbene with Dialkene 1, the chlorocarbene adds regioselectively across the alkene bond which lies syn to the C-Cl bond.

| |

Previously used mechanical methods such as MM2 do not account for secondary orbital interactions, and thus a new method which incorporates semi-empirical molecular orbital theory is used in this section to explain the observed selectivity.

In these experiments, MM2 is firstly used to "clean up" the geometry of the molecule and then the MOPAC/PM6 method is used to further optimise the molecule and to generate approximate molecular orbitals.

When a molecule has a certain symmetry, (Cs in the case of Dialkene 1), its molecular orbitals must also be of the same symmetry. When running the optimisation using the MOPAC/PM6 method, the molecular orbitals produced were not of Cs symmetry, therefore the MOPAC/RM1 method was used instead and this method did make MOs of Cs symmetry.

Molecular orbital control of reactivity

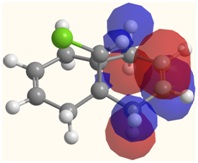

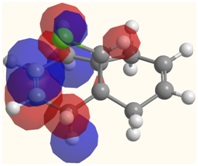

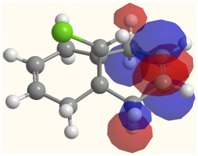

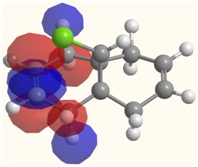

It can be expected that the highly electrophilic dichlorocarbene molecule would attack the Dialkene molecule at the most electron rich alkene bond, which, as shown in the HOMO image, is the C=C bond syn to the C-Cl bond.

The lack of reactivity at the C=C bond anti to the C-Cl bond can also be explained by looking at the LUMO and HOMO-1 molecules.

The HOMO-1 image visualises the molecular orbital which corrsponds to the filled π orbital on the C=C bond which lies anti to the C-Cl bond. Visual comparison of the LUMO and HOMO-1 orbitals reveals an overlap, indicating a favourable interaction between the two. The LUMO corresponds to the σ* antibonding C-Cl orbital, which, through its interaction with the HOMO-1 orbital in turn removes electron density from the anti C=C bond, thus reducing its nucleophilicity and making it less attractive to the electrophilic dichlorocarbene.

| HOMO-1 | HOMO |

|  |

| LUMO | LUMO+1 | LUMO+2 |

|  |  |

Vibrational Analysis

This part of the exercise looks into the effects that the hydrogenation of the anti C=C bond has on the vibrational stretching modes of the molecule Dialkene 1. The hydrogenation product is shown as Alkene 1.

To generate the vibrational modes, the molecules were optimised using the MM2 method before being submitted to the Gaussian Scan Cluster for further optimisation and vibrational analysis.

Table 6 illustrates the key stretching vibrational modes in both the Dialkene and Alkene molecules. The lower energy C=C stretch for the alkene anti to the C-Cl bond compared to the syn C=C bond arises from the fact that the anti C=C π bond donates electron density into the σ* C-Cl antibonding orbital. This in turn decreases the electron distribution within the C=C bond, making the bond weaker and therefore having a vibrational stretch fruequency lower than its syn counterpart.

The presence of donation from the anti alkene π orbital into the σ* C-Cl antibonding orbital is further confirmed when the anti C=C bond is hydrogenated to become an alkene bond. The C-Cl antibonding orbital is no longer accepting electron density, and therefore one would expect the bond strength to increase, which it does, by 9cm-1, a significant amount.

Vibrational analysis of substituted dialkenes

In this part of the experiment, the effects of replacing the substituents on the syn C=C bond were investigated. It was chosen to change the syn rather than anti substituents so that these previously overlooked effects may be studied and reported.

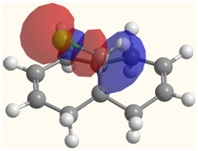

The substituents -BH2, -CN, -OH, -PMe2 and -SiH3 were used to replace one of the hydrogen atoms on the syn C=C bond before being optimised using MM2 and MOPAC/PM6 and vibrations generated by Gaussian. These molecules have been visualised in the images below.

|

|

|

|

|

From Table 7 it can be seen that, as a general rule, electron donating species such as -BH2 and -CN decrease the bond energy of the alkene, whereas electron donating groups like -OH increase the bond energy. The substituents containing larger atoms did not display concurrency with the findings, probably due to poor orbital overlap.

The effects that differing the substituents had on the strength of the C-Cl bond are very interesting. Again, as a general rule the electron withdrawing substituents increase the C-Cl bond energy, whereas the electron donating substituents decrease the C-Cl bond energy. The increase in C-Cl bond strength by the addition of an electron withdrawing substituent could arise from interaction between the π electron cloud of the syn alkene and the σ* C-Cl antibonding orbital which is not evident in the previous MO visualisations. It is possible that the electron withdrawing substituent has, by removing electron density from the π electron cloud, strengthened the C-Cl bond. The opposite effect would thus explain the weakening of the C-Cl bond by electron donating substituents.

|

Structure based Mini project using DFT-based Molecular orbital methods

Introduction to the project

This mini project looks at outcomes of the reaction of 2,4-Dichloroquinoline with a benzyl zinc reagent, focusing on products 1 and 2, which are regioisomers of one-another.

In 1999, Shiota and Yamamori investigated the reaction conditions required in order to selectively synthesise product 1 or 2 using the same starting materials[5].

They discovered that in order to solely synthesise product 2, they must use the (at the time) relatively underused cross-coupling method using Palladium as the catalyst in THF as the solvent. They found that using this method produced product 2 with a yield of 80% and did not produce any product 1 at all.

|

In order to synthesise product 1, they tried the more direct approach of nucleophilic substitution, initially using reagents which had previously been reported[6] to increase the nucleophilicities of organozinc reagents. It was found that these reagents induced little or no success in synthesising either product 1 or 2 and so their attention was turned to LiCl in DCM. This reaction reported a yield of 65% product 1 with no synthesis of product 2.

|

Molecule Characterisation

The aim of this project is to, by computational methods, predict the 1H NMR and IR spectra of products 1 and 2. By doing so the aim is to ascertain whether or not the products have been correctly characterised in the literature[5] and to see if the published spectra contain any abnormalities which may correspond to impurities.

1H NMR Calculations

Given the absence of 13C NMR data in the literature, it was decided to investigate the accuracy of the 1H NMR calculations. This would then provide an insight into whether or not the DTF based Molecular Orbitals methods could be used in the future to predict 1H NMR spectra.

For the 1H NMR calculations, the DFT=MPW1PW91 method was used to optimise the geometry, using a basis set of 6-31G(d,p). This optimised geometry was then used to calculate the 1H NMR chemical shifts using Gauge-Including Atomic Orbital (GIAO) approximations.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

From looking at the NMR data shown in Table 8, both for product 1 and product 2, it can be seen that the NMR predictions are in fairness not too far from the reported values.

It can very easily be seen that a limitation of using DFT based models to predict NMR specta is that it cannot identify multiplicity, which is why quite often 2 calculated values are assigned to one literature shift.

It can be said that, with a maximum deviation from the literature of 0.8ppm, the calculated 1H NMR data is accurate enough to be used as a valid technique for the prediction of such data.

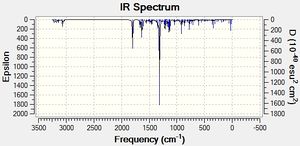

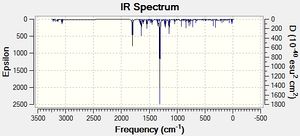

IR Calculations

IR calculations of products 1 and 2 were run using B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) to optimise the geometry of the molecules and to calculate the vibrational modes. The IR calculations were used as a secondary method of characterising products 1 and 2, being less informative in terms of information provided, especially as the literature only reports 3 or 4 of the stretches.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 7 reports the IR values calculated by Gaussian and compares them to those reported in the literature. Immediately it can be seen that the calculated IR vibrational energies overestimate the reported values by ~100cm-1, which is quite a large overestimation. This inaccuracy in the calculated spectra can possibly be attributed to the approximations used in the computational methods, which may not account for solvent effects or suchlike.

An unusual peak is reported for product 2 in the literature at 3438cm-1 which cannot be correlated to any peak in the calculated spectrum, whose highest energy peak is reported at 3229cm-1 for a C-H stretch. Judging from the calculated spectrum and based on the fact that the computational method over-predicts the vibrational energy by about 100cm-1 , it would appear that this stretch in the literature corresponds to some sort of impurity in the sample, possibly water contamination.

Conclusion of the Mini-Project

Judging by the calculated results obtained for the 1H NMR and IR spectra and having compared them to the literature values, it can be concluded that (for this reaction at least) computational methods are ineffective.

The lack of difference in 1H NMR chemical shift between products 1 and 2 caused a problem in that it was difficult to distinguish between the two from the literature values, never-mind the computed values. Were the literature to have contained 13C NMR, it is likely that this would have contained an amount of difference in chemical shift between the two products which would enable the computational method to be used effectively in determining the differences between the products.

In this project, the IR calculations had the potential to be able to distinguish between products 1 and 2, given that the frequencies of the two products reported in the literature were sufficiently dissimilar. It was therefore disappointing to discover that the calculated IR spectra were unable to distinguish between the vibrational modes of the two products. For example, the literature reported stretching frequencies of the C=O stretch varied by 14cm-1, whereas the computational method only reported a difference in energy of 1cm-1.

Maybe were this reaction computed using more advanced methods, it would be possible to easily distinguish between the two regioisomers by 1H NMR or IR spectroscopy but as it stands, it is not feasible to use the methods used in this lab course.

Conclusion

In this module, MM2 and MMFF94 mechanical methods were used to minimise the energy of a molecule by changing the geometry and working to decrease the overall potential energy. These methods have limited uses and were often used later on in more complicated calculations to perform an initial quick 'clean up' of the molecule's geometry.

The semi-empirical molecular orbital theory methods MOPAC/PM6 and MOPAC/RM1 were then used to give a rough approximation of molecular orbitals in order that orbitals could be visualised and interpreted so that the molecule's reactivity could be explained. These methods were always preceded by a molecular mechanics 'clean up' and were flawed in that the user had to keep a close eye on which method was used in order to obey symmetry rules.

The mini-project part of the module used DFT-based Molecular orbital methods to obtain predicted NMR and IR spectra. These methods were always preceded by an MM2 'clean up' and a MOPAC/PM6 geometry optimisation. The limitations of these methods are discussed above in the mini-project conclusion.

References and Citations

- ↑ Paul D. Bartlett, Irving S. Goldstein; J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1947, 69 (10), 2553 DOI:10.1021/ja01202a501

- ↑ Pierluigi Caramella, Paolo Quadrelli and Lucio Toma; J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2002, 124 (7), 1130–1131 DOI:10.1021/ja016622h

- ↑ William L. Jorgensen, Dongchul Lim, James F. Blake; J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1993, 115 (7), 2936–2942DOI:10.1021/ja00060a048

- ↑ Wilhelm F. Maier, Paul Von Rague Schleyer; J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103 (8), 1891–1900 DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Takeshi Shiota and Teruo Yamamori; J. Org. Chem., 1999, 64 (2), 453–457 DOI:10.1021/jo981423a

- ↑ M. W. Rathke, H. Yu; J. Org. Chem., 1972, 37, 1732 DOI:10.1021/jo00976a013

- ↑ Product 1 NMR DOI:10042/to-7389

- ↑ Product 2 NMR DOI:10042/to-7391

- ↑ Product 1 IR DOI:10042/to-7439

- ↑ Product 2 IR DOI:10042/to-7438