Rep:Mod:zyc97mongmong

From: Zhou Yucheng

Exercise 1: The Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

Dimerisation of Cylcopentadiene

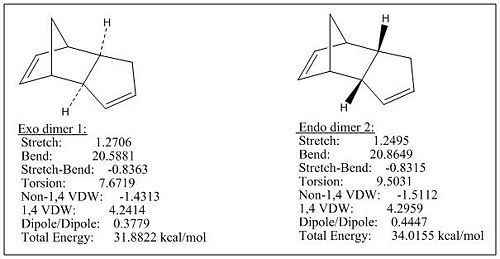

Cyclopentadiene dimerisation could give rise to 2 dimers, one is exo dimer 1 and the other one is endo dimer 2. According to the resulted total energies of the above two dimmers, formation of the exo dimer 1 is thermodynamically more favourable than endo dimer 2 by ca. 2.1 kcal/mol. However, the dimerisation produces specifically the endo dimer 2 rather than the exo dimer 1. This is because the MM2 only gives out the energy of the formed compound without considering the kinetics, while the cyclopentadiene dimerisation is under kinetic control and the endo dimer 2 undergoes lower TS than exo dimer 1 (see Fig 1).

|

|

|

Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene

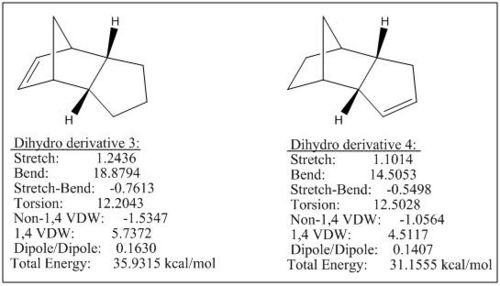

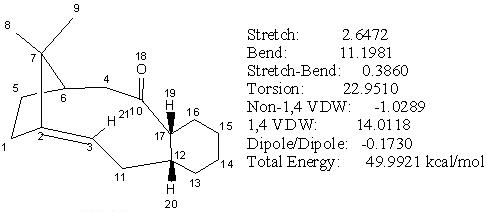

The hydrogenation of the endo dimer 2 gives dihydro derivatives 3 or 4. By comparing the total energies of the formed dihydro derivatives, the species 4 is at the lower energy than species 3 by ca. 5kcal/mol, leading to a more favourable formation of dihydro derivative 4 under thermodynamic control. From the above data, we can see the most significant factor influencing the total energy is the bending term and the rest (apart from the torsion term) all positioned at higher energies for species 3 than species 4. The differences of torsion in species 3 and 4 is less than 0.3 kcal/mol which is a very weak factor and will not alternate the fact that the total energy of the dihydro derivative 4 being lower than dihydro derivative 3 (see Fig 2).

|

|

|

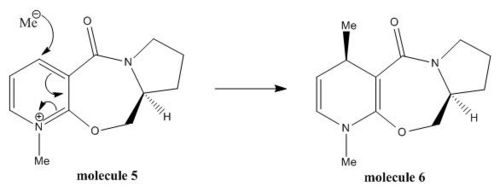

Exercise 2: Stereochemistry of Nucleophilic Addition to a Pyridinium Ring

Reaction Mechanism 1:

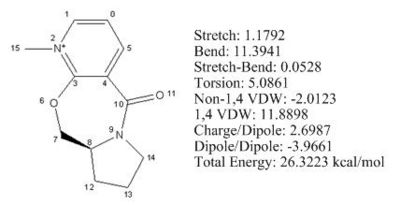

Minimisation of Total Energy for Molecule 5:

The initial total energy of the molecule 5 was 26.3 kcal/mol obtained by applying MM2. The optimisation for the total energy of molecule 5 was done by changing (e.g. stretching) the spatial arrangement of the atoms numbered 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11, as well as atoms 12, 13 and 14. No change in energy was observed when altering the spatial positions of carbon 12, 13 and 14. However, when stretching the C7 and carbonyl group (C10, O11) the total energy reduced to 25.6 kcal/mol after running MM2, which indicated these substituents had a significant influence on the total energy. The reason for not altering the spatial positions of the atoms involved in aromatic ring is because the lowest energy configuration of the aromatic system is fixed to be planar, and so changing the position of aromatic atoms makes no difference to the total energy of the molecule (see Fig 4).

|

The dihedral angel O(11)-C(10),C(4)-C(3): 141.0⁰ (see Fig 5)  |

|

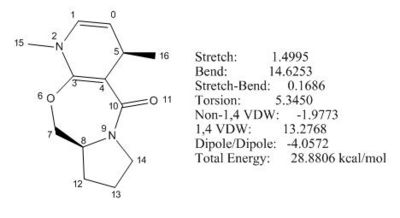

Minimisation of Total Energy for Molecule 6:

The initial total energy of molecule 6 was obtained 28.88 kcal/mol under MM2 . The optimisation for its total energy was performed in a similar way as for molecule 5, so C7 and carbonyl group (C10, O11) were stretched and the energy lowered slightly to 28.42 kcal/mol under MM2. The interesting point here is that the product (molecule 6) is thermodynamically less stable than the starting material (molecule 5) by ca.3 kcal/mol due to the disruption of aromaticity in molecule 5 and increased strain by introducing a methyl group in molecule 6. This implies that the reaction is under kinetic control (see Fig 6).

|

The dihedral angel O(11)-C(10),C(4)-C(3): 147.0⁰ (see Fig 7)  |

|

Conclusion for Reaction 1[1]:

The high region- and stereoselection for addition of Grignard reagents is due to the coordination between the Grignard reagent and the amide oxygen atom (see Fig 13).The chelating of carbonyl oxygen to magnesium of Grignard reagent leads to a stabilised 6 membered TS, which then allows the nucleophilic attack of the methyl anion at carbon 5 from the same face as the carbonyl group and gives a stabilised magnesium enolate. The stabilisation of TS gives the kinetic advantage of the reaction, and hence the reaction is under kinetic control since the product is thermodynamically less stable than the starting material due to the presence of steric strain (electronic repulsion) between the methyl and carbonyl group being at the same plane.

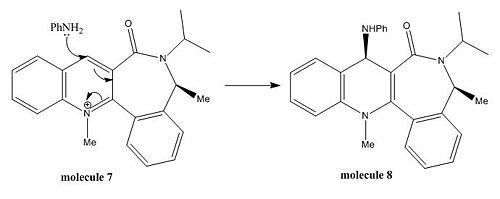

Reaction Mechanism 2:

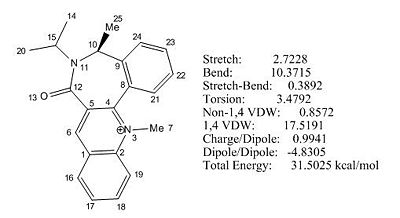

Minimisation of Total Energy for Molecule 7:

The initial total energy of molecule 7 obtained under MM2 was 31.5025 kcal/mol. A more stable configuration with energy 14.93 kcal/mol was achieved under MM2 by first removing all the hydrogens, followed by ring flip and then adding all the hydrogens back. (see Fig 9).

|

The dihedral angel O(13)-C(12),C(5)-C(4): 135.0⁰ (see Fig 10)  |

|

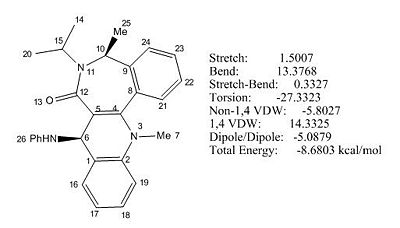

Minimisation of Total Energy for Molecule 8:

The initial total energy obtained under MM2 was -8.68 kcal/mol, and further optimisation of the molecular energy was done in a similar way as for molecule 7 and the optimised energy was -17.86 kcal/mol under MM2. The formation of molecule 8 is thermodynamically favoured since its optimised energy was lower than molecule 7 by ca. 33 kcal/mol and therefore the reaction is under thermodynamic control. (See Fig 11).

|

The dihedral angel O(13)-C(12),C(5)-C(4): 142.0⁰ (see Fig 12)  |

|

Conclusion for Reaction 2[2]:

The jmol of optimised configuration of molecule 7 shows that the carbonyl group is pointing in the opposite direction to which the methyl group (number 25) is oriented. Therefore, unlike the previous reaction, this reaction process cannot obtain a stabilising complexation with the carbonyl oxygen and the bulky nucleophile PhNH2 prefers to attack from the opposite face where the carbonyl group is pointing so as to minimise the steric clash. As a conclusion, the stereoselectivity of this reaction mainly comes from the steric control of the carbonyl lactam which determines the orientation of PhNH2 in product molecule 8.

Exercise 3: Stereochemistry and Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

Minimisation of Total Energy for Isomer 10:

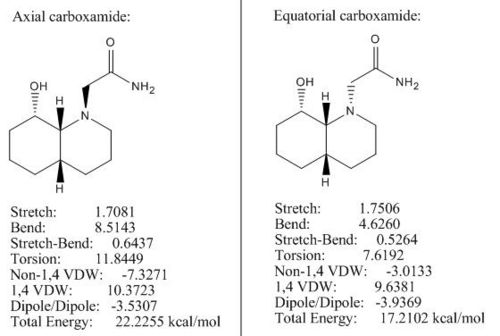

The initial total energy of the intermediate 10 was 49.99 kcal/mol under MM2. However, a slightly lower energy configuration of 42.16 kcal/mol was obtained by stretching the carbonyl group (C(10)=O(18)) away from the ring and moving the carbon atom, C(6), out of the position. The resulting form has carbonyl group pointing in the same direction as the bridging methylene carbon, C(7), and the lowest energy configuration mainly came from lowering the bending energy of the system. The cyclohexane ring in the optimised form of intermediate 10 (shown in jmol below) adopted a twisted boat conformation, which is in agreement with reference[3] (see Fig 14.1).

Minimisation of Total Energy for Isomer 11:

The initial energy of intermediate 11 was 50.03 kcal/mol under MM2. The optimisation was done in a similar manner to intermediate 10 and a slightly lower conformation with energy 49.67 kcal/mol obtained. Further minimisation in energy was achieved by removing all the hydrogens on cyclohexane, and then adjust the cylohexane ring into chair like conformation. The resulting energy without hydrogens was 28.61 kcal/mol and with hydrogens was 43.17 kcal/mol. The optimised isomer 11 has cyclohexane ring in a chair conformation which is in agreement with reference[3] and the carbonyl group pointed in opposite direction to the bridging methylene carbon, C(7) (see Fig 14.2).

Reason for slow reaction of alkene[4]:

In most of the cases, the alkene next to a bridgehead in a cyclo-system is expected to be unstable due to the significant strain. However, according to Bredt’s Rule which states a double bond cannot be placed at the bridgehead of a bridged ring system, unless the rings are large enough. In general, these kind of alkene double bonds are hyperstable. In this exercise, both isomers contains more 8 carbon atoms in the cyclo-systems which implies being part of large membered rings the alkene double bond is relatively stable and so reacts slowly.

Conclusion[3]:

Isomer 10 has cyclohexane ring (c-ring) in twist boat conformation, while the isomer 11 adopts c-ring in chair conformation. The resulted structure of isomer 10 comes from the bridged E-cyclononenone in the central position being sufficiently rigidified to lock the fused c-ring into a thermodynamically unstable twist-boat conformation. In the case of isomer 11 the non-bonded transannular interactions are enhanced within the ring core of isomer structure when the chair like conformation is adopted. Both isomer have very close energies, and based on which it is very difficult to tell which isomer will form. However, isomer 10 is most likely to exist in a relatively large ratio compared to isomer 11 since isomer 10 have energy of 1.01 kcal/mol lower than that of isomer 11 under MM2.

Exercise 4: How one might induce room temperature hydrolysis of a peptide

Reaction Schemes 3 & 4:

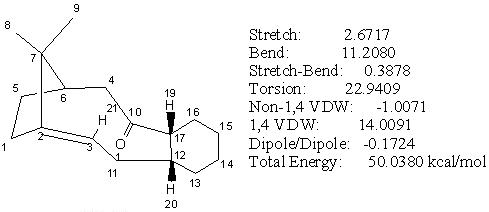

This exercise introduced two reactions (see Fig 15) which only differed in the conformation of starting materials and required kinetic arguments to explain why the half life for hydrolysis of reaction 2 is much faster than for reaction 3.

The geometry of both isomers in above reactions is different in the sense that the reaction 3 has cis-decline while the reaction 4 has trans-decline and both geometrical structures suffered a relative amount of stain. However, the alcohol and the amine groups in both cis and trans structures are not steric compressed, which explains why their half lifetime for hydrolysis are less than 500 years.

Both declines have two diastereoisomers, one has carboxamide in the equatorial position while the other has carboxamide in the axial position. Now we need to analyse which diastereoisomer is more stable for each decline, since the one with higher stability is the major form of the starting material in the reaction.

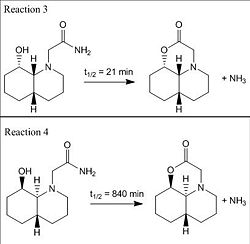

Diastereoisomers of cis-decline:

Both cis-declines (see Fig 16) have OH group in the equatorial position, so by altering the carboxamide group we can make two diastereoisomers and rationalise which one is more stable by applying MM2.

Under MM2 both diastereoisomers adjusted themselves into chair conformation to obtain lowest possible energies. The optimised configuration for axial carboxamide is 22.22 kcal/mol which is 5.01 kcal/mol higher than the optimised energy (17.21 kcal/mol) for equatorial carboxamide. The energy difference is very close to the literature value (5.0 kcal/mol)[5] and it is expected that the energy outcome for axial carboxamide should be higher than for equatorial one due to two reasons:

1) The axial substituents (e.g. axial carboxamide) destabilise the isomer by syn-diaxial interactions.

2) The equatorial carboxamide is stabilised by intra-molecular H-bonding between the oxygen lone pair of the OH group and the hydrogen atom on amine.

Therefore, the major form of cis-decline in the reaction is where carboxamide is in equatorial position.

|

|

|

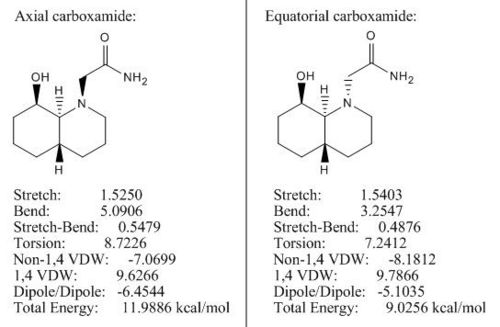

Diastereoisomers of trans-decline:

Both trans-declines (see Fig 17) have OH group in the axial position, so by altering the carboxamide group we can make two diastereoisomers and rationalise which one is more stable by applying MM2.

Under MM2 both trans-declines adopted chair conformation to stabilise the structures. The optimised configuration for axial carboxamide is 11.99 kcal/mol which is 2.97 kcal/mol higher than the optimised energy (9.02 kcal/mol) for equatorial carboxamide. The energy difference is very close to the literature value (3.1 kcal/mol)[5] and the rationalisation for trans-decline is similar to cis-decline:

1) The axial substituents (e.g. axial carboxamide) destabilise the isomer by syn-diaxial interactions.

2) The equatorial carboxamide is stabilised by intra-molecular H-bonding between the oxygen lone pair of the OH group and the hydrogen atom on amine.

Therefore, the major form of trans-decline in the reaction is where carboxamide is in equatorial position.

|

|

|

Summary:

Explanation for why cis-decline reacts faster than the trans-decline5:

The previous analysis found out the major diastereoisomers for both cis and trans declines in the reactions and this part of exercise is going to explain why the cis-decline hydrolyses faster than the trans-decline using the previously found major diastereoisomers.

The diagram (see Fig 19) shows the overall reaction schemes for cis and trans-declines:

Both of the above reactions undergo intra-molecular nucleophilic attack which requires the right orientations of both hydroxyl group and the carboxamide so that the hydroxyl group is close enough to the carboxamide as well as attacking the carbonyl group from the correct trajectory.

In the case of cis-decline, the major isomer which has the equatorial carboxamide group in the right orientation to allow for the intra-molecular nucleophilic attack from hydroxyl group (see the above reaction scheme for cis-decline).

However, in the case of trans-decline, the reaction proceeds via a minor isomer which has the carboxaimde group in the axial position that renders the reaction undergo intra-molecular nucleophilic attack. This is because the minor isomer of the trans-decline brings the hydroxyl group and the carboxamide closer together in the right orientation. And the energy cost for converting the equatorial carboxamide (major isomer) to the axial carboxamide (minor isomer) is 2.97 kcal/mol which results in a higher activation energy for the trans-decline to react. This explains the reason why the hydrolysis of cis-decline is much faster than that of trans-decline.

Exercise 5: Regioselective Addition of Dichlorocarbene

This exercise illustrates the orbital control of reactivity in the reaction of compound 12 with electrophiles which can be modelled once knowing the geometry of compound 12 with the calculated orbital energies and their corresponding graphic display. In this exercise we explored a quantum mechanical treatment of a molecule transited from purely classical mechanical treatment, including the wave description of the electrons.

Minimisation of Total Energy for Molecule 12:

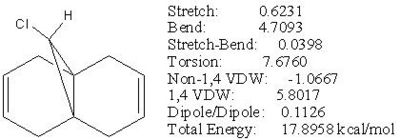

Firstly, the energy of compound 12 was minimised using MM2.

Secondly, an approximate representation of the valence-electron molecular wavefunction was obtained by HF/STO-3G self-consistent –field MO method. The graphic representation of HOMO-1, HOMO, LUMO, LUMO+1 and LUMO+2 were obtained as following (Fig 21 - Fig 25):

-

Fig 21: HOMO-1

-

Fig 22: HOMO

-

Fig 23: LUMO

-

Fig 24: LUMO+1

-

Fig 25: LUMO+2

In both a frontier orbital and an electrostatic sense, the π orbital of endo double bond (HOMO) is more nucleophilic than the π orbital of exo double bond (HOMO-1). This is due to stabilising antiperiplanar interaction between the occupied exo-π orbital (HOMO-1) and the empty C-Cl σ*orbital (LUMO+2), therefore reduces the electron-density in exo double bond compared to endo double bond[6].

This method in comparison with MM2, may give a better geometry with minimised energy, but in this exercise the configuration of molecule 12 turned out very similar from both method.

Thirdly, after optimising its geometry using HF/STO-3G, the file with correct format saved as .gjf form was submitted to the SCAN and IR spectrum and data were resulted.

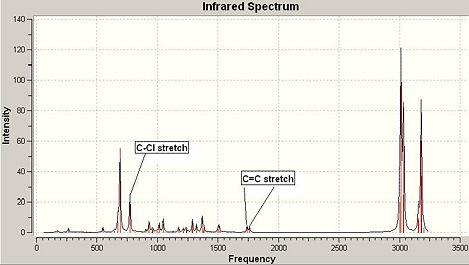

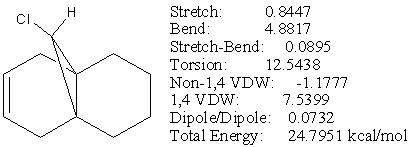

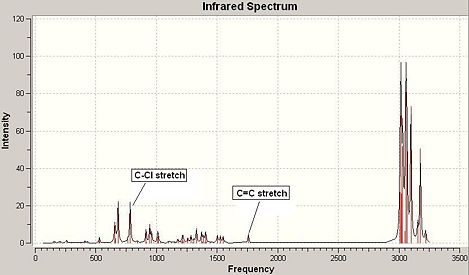

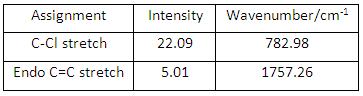

IR Spectrum of Compound 12:

|

|

https://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php/Image:Zyc_IR_molecule_12.out

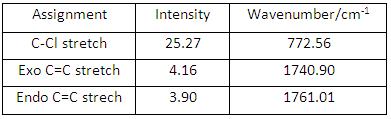

Compound 12 had up to 69 vibrational modes and each can be animated using GaussView, however, only the characteristic ones were noted down here and analysed further (see Fig 26). The table (See Fig 27) shows the C-Cl stretch had a much larger intensity than both C=C stretches, the reason comes from C-Cl stretch can give rise to a larger change in dipole moment compared to C=C stretches.

Minimisation of Energy for Molecule 13:

Compound 13 is the hydrogenated form (the exo double bond is hydrogenated) of compound 12. The process to minimise energy for compound 13 followed the exactly the same steps as compound 12.

Firstly, using MM2 to minimise the energy and the results shown in Fig 28.

The optimised compound 13 is destabilised by about 7 kcal/mol compared to compound 12. This is because compound 13 lost the stabilising antiperiplanar interaction between the occupied exo-π orbital and the empty C-Cl σ*orbital, and resulted an increased syn diaxial interaction from the added hydrogens. The optimised configuration had cyclohexane in boat conformation which comes from the bridgehead being at the ring fusing carbons that lock the boat conformation.

Secondly, the configuration was further optimised using HF/STO-3G self-consistent-field MO method. The resulted geometry was about the same as the one obtained from MM2.

Thirdly, after optimising its geometry using HF/STO-3G, the file with correct format saved as .gjf form was submitted to the SCAN and IR spectrum and data were resulted.

IR Spectrum of Compound 13:

|

|

https://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php/Image:Zyc_IR_molecule13.out

Compound 13 had up to 75 vibrational modes (see Fig 29) and each can be animated using GaussView, however, only the characteristic ones were noted down here and analysed further. The table (see Fig 30) shows the C-Cl stretch and endo C=C stretch.

Conclusion[6]:

In comparison with the compound 12 IR spectrum, compound 13 had C-Cl stretch occurred at a higher wavenumber by about 10cm-1 which implies that compound 13 had stronger C-Cl bond than compound 12. This is because in compound 12 the C-Cl σ* lobe orientated in such a direction that it can overlap with the exo C=C π orbital giving rise to an electron donation from exo double bond into the C-Cl empty σ*orbital resulting a reduced C-Cl bond order. Therefore, the resulted longer, weaker C-Cl bond in compound 12 occurs at a lower wavenumber in IR spectrum. This stabilising app interaction disappeared in compound 13 as it only contains an endo double bond which can not overlap with the C-Cl empty σ*orbital, so the C-Cl bond in compound 13 is stronger and occurs at higher wavenumber in IR spectrum.

Mini Project: Computational Analysis on Modelling A Concise Total Synthesis of Diospongins A and B

Introduction:

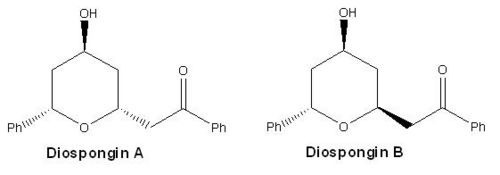

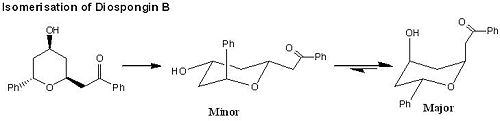

Diospongins A and B are recognised as cyclic 1,7-diarylheptanoids, presenting in a large variety of natural products and have been successfully isolated from the rhizomes of Dioscorea spongiosa in 2004 by a method of bioassay-guided fractionation[7],[8]. Diospongin A consists a 2,6-cis-substituted tetrahydro-2H-pyran ring, and Diospongin B contains a 2,6-trans-substituted tetrahydro-2H-pyran ring, so they are diastereoisomers (see Fig 31). In this mini project, we are going to study a concise total synthesis of (-)-diospongins A and B by the means of computational analysis and compare the experimental data from IR, NMR and optical rotation view with the reference values.

The Reaction Scheme for Diospongins A and B[7]:

The key synthetic steps involve a stereoselective reduction of β-keto ester[9], the Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons[10] and intramolecular oxy-Michael[11] reactions (see Fig 32 ).

Analyse the energies of Diospongins A and B:

Before further optimising the energies of diospongins A and B we need to decide which diastereoisomeric forms of diospongins A and B are more stable relative to the others and then we can use the favoured geometry for later IR, NMR and optical rotation analysis, since the one with higher stability is the major form of the product.

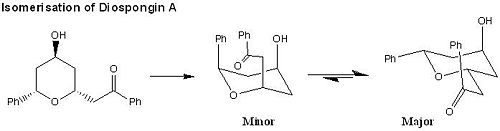

Diospongin A:

|

|

Under MM2, both A(1) and A(2) have tetrahydro-2H-pyran ring in chair conformation and the minimised energy of Optimised A(1) is lower than that of Optimised A(2) by about 113 kcal/mol which is a significantly large difference in energy. The reason why A(2) is so much more unstable than A(1) is because A(2) bears significant 2x 1,3-dixial interaction between OH and Ph & CH2COHPh which is absent in A(1) conformation. Therefore A(1) is a much thermodynamically favoured conformation and exists as the major form of Diospongin A. The later analyses will only use A(1) conformation.

Please see the link below which shows the optimised Diospongin A(1) after DFT:

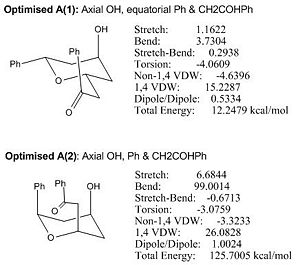

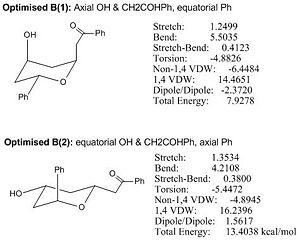

Diospongin B:

|

|

Under MM2, both B(1) and B(2) have tetrahydro-2H-pyran ring in chair conformation and the minimised energy of Optimised B(1) is lower than that of Optimised B(2) by nearly half, which is a relatively big difference in energy. B(1) conformation is stabilised by intramolecular H-bonding between axial OH hydrogen and axial carbonyl oxygen and this H-bonding stabilisation overcomes the destabilising 1,3-dixial interactions present in B(1), and hence gives rise to a more stable conformation B(1) since the B(2) cannot form H-bonding between equatorial OH hydrogen and equatorial carbonyl oxygen. The later analyses will only use B(1) conformation.

Please see the link below which shows the optimised Diospongin B(1) after DFT:

Results and Discussion:

The files of Diospongins A(1) and B(1) with correct format saved as .gjf form was submitted to the SCAN and IR, 13C NMR spectra as well as optical rotations were resulted and compared with the reference data.

NMR:

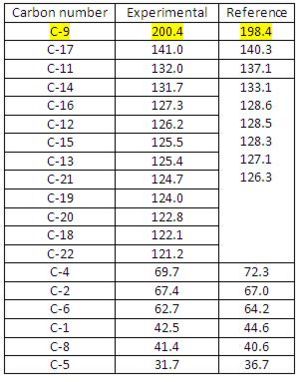

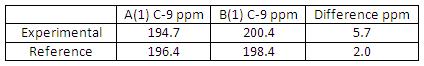

13C NMR Analysis for Diospongin A(1):

The data obtained from GIAO approach is compared with the reference data[7] (see Fig 36). And Fig 35.1 shows the configuration of Diospongin A(1) with all atoms labelled (http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-1683).

|

|

|

The experimental results are in good match with the reference data and the mean difference is within ±2 which is reasonable for 13C NMR spectrum and the minor differences are expected since the experimental data comes from a computational modelling and there is a difference between theoretical and experimental results. The GIAO approach assigned each shift to a corresponding carbon, however, the reference data only gives 8 shifts assigned with the 12 phenyl carbons. This is due to the NMR techniques and equipments that are unable to resolve each single carbon in very similar environments (e.g. phenyl carbons).

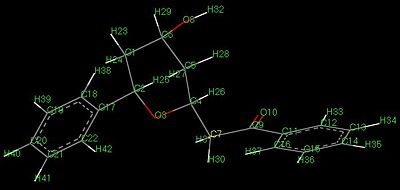

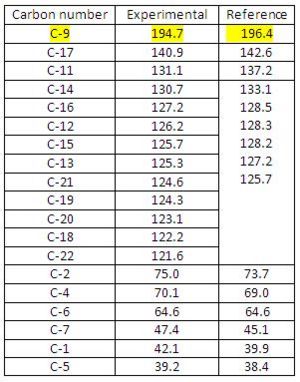

13C NMR Analysis for Diospongin B(1):

The data obtained from GIAO approach is compared with the reference data[7] (see Fig 38) and Fig 37.1 shows the configuration of Diospongin B(1) with all atoms labelled. http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-1682

|

|

|

Diospongin B(1) also obtained a good experimental 13C NMR spectrum with respect to the Reference and the mean difference is also within ±2. The same issue as for the Diospongin A(1) 13C NMR spectrum arises here, the reference data cannot assign each phenyl carbon with a corresponding shift and the reasons are the same as explained in Diospongin A(1) 13C NMR spectrum case.

Now by comparing the Diospongins A(1) and B(1) 13C NMR spectra we can spot out that there is a significant difference in C-9 chemical shift for A(1) and B(1) in both experimental and reference data relative to the other carbon chemical shifts (see Fig 39). Diospongins A(1) and B(1) are diastereoisomers with very similar spatial configuration so their NMR spectra are more or less the same. However, B(1) C-9 chemical shift appeared at a higher ppm than A(1) C-9, this means B(1) C-9 is more deshielded than A(1) C-9. The reason is due to H-bonding formation between C(9)=O(10) oxygen and O(8)-H(32) hydrogen in B(1) and consequently lone pair donation from O(10) to form H-bond increases its electron-withdrawing ability and therefore results a more deshielded C-9. This H-bonding is absent in A(1), therefore A(1) C-9 is less deshielded comparing to B(1) C-9.

IR:

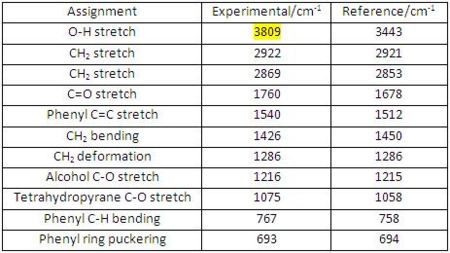

IR Analysis for Diospongin A(1):

The data obtained from computational (experimental) analysis is compared with the reference data[7] (see Fig 41). The experimental values are in good agreement with the reference data.

|

|

(http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-1645)

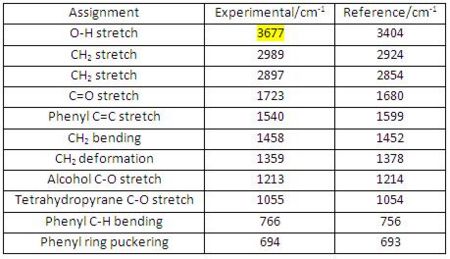

IR Analysis for Diospongin B(1):

The data obtained from computational (experimental) analysis is compared with the reference data[7] (see Fig 43). The experimental values are in good agreement with the reference data.

|

|

In comparison with the IR spectrum of Diospongin A, the OH stretch of Diospongin B occurs at a much lower wavenumber this is because B has intramolecular H-bonding from carbonyl oxygen lone pair to OH hydrogen and so reduces the O-H bond order (i.e. weakens the O-H bond), therefore, the corresponding IR absorption appears at a lower wavenumber (http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-1681).

Optical Rotation:

There are quite big differences between experimental and reference data for both Diospongins A(1) and B(1) optical rotations (see Fig 43). The presence of such big differences between experimental and reference data is due to various reasons, such as unknown concentrations, temperatures and units for both A(1) and B(1) experimental optical rotation measurement by computational analysis and therefore there is not such a reference data can be compared with. However, the signs are all negative and indicating the right enantiomeric configurations of A(1) and B(1) obtained under computational modelling (http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-1680).

Conclusion:

In this min project, the more stable conformation of Diospongins A and B were found out by MM2 and optimised further by HF and then DFT methods. IR, 13C NMR and the optical rotation of the optimised conformations of A(1) and B(2) were computationally analysed and compared with the reference data. IR and 13C NMR data of both diospongins A(1) and B(1) were matched well with the reference values, and as for optical rotation, the signs of values for diospongins A(1) and B(1) were the same as the reference ones which implied right enantiomeric configurations of computationally obtained diospongins A and B. As an overall, this mini project was conducted fairly successful and the computational analysis is a very powerful tool for studying organic synthesis and gave very good and reliable results for this mini project.

Reference

1. Arthur G. Schultz, Lawrence Flood, and James P. Springer. J. Org. Chem., 1986, 51 (6), 838-841

2. S. Leleu et al. / Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 15 (2004) 3919–3928

3. Steven W. Elmorel and Leo A. Paquette,Tetrahedron Letters, Vo1.32, No.3. pp 319.322, 1991

4. Wilhelm F. Maier, and Paul Von Rague Schleyer. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103 (8), 1891-1900

5. Nicolette M. Fernandes, Fabienne Fache, Mari Rosen, Phuong-Lan Nguyen, and David E. Hansen. J.Org. Chem., 2008, 73 (16), 6413-6416.

6. Brian Halton, Roland Boese and Henry S. Rzepa. J. CHEM. SOC. PERKIN TRANS. z 1992

7. Gowravaram Sabitha, Pannala Padmaja, and Jhillu S. Yadav .Helvetica Chimica Acta – Vol. 91 (2008)

8. Cyril Bressy, Florent Allais, Janine Cossy. SYNLETT 2006, No. 20, pp 3455–345618.12.206

9. G. Vidari, S. Ferrino, P. A. Grieco, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 3539.

10. G. Solladie, N. Wilb, C. Bauder, J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 5447.

11. H. Kigoshi, M. Kita, S. Ogawa, M. Itoh, D. Uemura, Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 957.