Rep:Mod:yi111c

Cyclopentadiene dimer

Cyclopentadiene dimerises to afford two isomers; exo- and endo-dimer as shown in Isomer 1 and Isomer 2 respectively below.

Isomers of dicyclopentadiene

| Optimised Energies | Isomer 1 (exo) | Isomer 2 (endo) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Total bond stretching energy /kcalmol-1 | 3.54301 | 3.46743 | ||||||

| Total angle bending energy /kcalmol-1 | 30.77268 | 33.19131 | ||||||

| Total torsional energy /kcalmol-1 | -2.73103 | -2.94945 | ||||||

| Total van der Waals energy /kcalmol-1 | 12.80164 | 12.35726 | ||||||

| Total electrostatic energy /kcalmol-1 | 13.01367 | 14.18431 | ||||||

| Total Energy /kcalmol-1 | 55.37344 | 58.19070 |

As discovered by _____ [Ref], and as Table 1 shows, the lower energy exo-diastreomer is the more thermodynamically stable product however the kinetic endo-diastereomer is formed. This is due to kinetic control of the reaction where the endo form has a lower transition state according to Hammonds Postulate, otherwise the more thermodynamically favourable exo conformer would be seen. One can explain this phenomenon by considering frontier orbital theory. The HOMO of the cyclopentadiene acting as a the diene (Ψ2) is electron rich and the LUMO of the other acting as the dienophile (π* of one C=C double bond) is electron deficient, which leads to a smaller difference in energy and better overlap. As the two molecules approach each other, one can see that the "spare" double bond dienophile has the correct symmetry of the p-orbitals to align and interact with the empty p-orbitals at the "back" of the dieneophile. This through-space interaction stabilises the transition state of the endo form. This could also explain the lower bnd energy of the endo product being the greatest contributor to its lower total energy.

Hydrogenation of dicyclopentadiene

Mono-hydrogenation of the endo dimer (Isomer 2) gives Isomer 3 and Isomer 4 as shown below.

| Optimised Energies | Isomer 3 | Isomer 4 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Total bond stretching energy /kcalmol-1 | 3.31190 | 2.82311 | ||||||

| Total angle bending energy /kcalmol-1 | 31.93610 | 24.68539 | ||||||

| Total torsional energy /kcalmol-1 | -1.46985 | -0.37833 | ||||||

| Total van der Waals energy /kcalmol-1 | 13.63724 | 10.63721 | ||||||

| Total electrostatic energy /kcalmol-1 | 5.11949 | 5.14702 | ||||||

| Total Energy /kcalmol-1 | 50.44573 = 211.206 kJ/mol | 41.25749 = 172.737 kJ/mol |

All the relative contributions to the total energy are lower in Isomer 4 which is ~9kcalmol-1 lower in energy than Isomer 3. The str energy is lower due to the lower ring strain on the 6-membered ring which does not possess a double bond in addition to a methyl bridge. The difference in bond angles at the unhydrogenated C=C double bond (Isomer 3) and the hydrogenated C-C bond (Isomer 4) can be seen here where it is 103 °as opposed to 107 °in the less strained conformer. The major contribution maybe the torsional energy difference where the -CH2 hydrogens on the cyclopentane ring in Isomer 4 are gauche but are eclipsed in Isomer 3 which contributes again to the lowering of the total energy. It is also interesting to see that the ring junction C-C bond (joining the 6- and 5- membered rings) is 1.563 Â in Isomer 3 and 1.549 Â in Isomer 4, highlighting the relaxation of ring strain upon hydrogenation of the cyclopentene ring. Whilst the electrostatic energies are similar as the composition of both molecules are the same, the aforementioned differences allow Isomer 4 to be lower in energy, therefore the thermodynamic product.

As for the kinetic product, one must examine more transition states of this reaction and to determine which conformer proceeds via the lower.

Atropisomerism

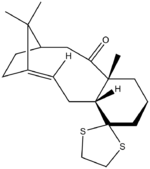

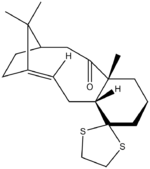

Isomer 10 is lower in energy by ~10 kcalmol-1 than Isomer 9. Initial examination of the structure may lead to attributing that to the decrease in transannular strain by orientation of the C=O carbonyl pointing down on the opposite face of the methyl bridge. However investigation into "hyperstable" alkenes[1] by Maier has revealed such olefins containing less strain compared to their parent hydrocarbon are slow to react due to the twisted cage-like structure. From a molecular orbital point of view, this reduces the π overlap i.e. the HOMO-LUMO.

Spectroscopic Simulation using Quantum Mechanics

1H and 13C NMR of one of the two isomers of an intermediate related to the synthesis of taxol; Isomer 17 and Isomer 18 were calculated. The energies were calculated first and the more stable form used to obtain spectroscopic values as the lower is more stable and observable to give experimental values in literature for comparison.

Isomer 18 is the thermodynamic product of the two conformers, being lower in energy by 4.3 kcalmol-1 than Isomer 17 which is consistent with reports in literature[2]. Paquette has noted that the methyl substituent α to the C=O carbonly group is brought closer to the bridgehead methyl groups in this conformation which opposes what is expected in terms of a steric argument. The vdW energy is lower still due to the overiding factor of the C=O being tucked under the main ring.

1H NMR calculation of Isomer 18

| Hydrogen number | Chemical shift /ppm | Splitting | Proton count | Spectrum (Click to enlarge) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular model | Literature[2] | Literature | Literature | ||

| 20 | 5.99 | 5.21 | m | 1 |

|

| 35, 32 | 3.13 | 3.00-2.00 | m | 6 | |

| 34 | 3.00 | 2.70-2.35 | m | 4 | |

| 33, 37 | 2.93 | 2.20-1.70 | m | 6 | |

| 43 | 2.81 | 1.58 | t, J = 5.4 Hz | 1 | |

| 23 | 2.55 | 1.50-2.00 | m | 3 | |

| 41 | 2.47 | 1.10 | s | 3 | |

| 28, 46 | 2.34 | 1.07 | s | 3 | |

| 26 | 2.28 | 1.03 | s | 3 | |

| 44, 40 | 2.00 | ||||

| 27, 42 | 1.85 | ||||

| 51 | 1.65 | ||||

| 38 | 1.58 | ||||

| 48, 30 | 1.51 | ||||

| 29 | 1.36 | ||||

| 47 | 1.30 | ||||

| 31, 52 | 1.22 | ||||

| 53, 50, 49 | 0.95 | ||||

| 45 | 0.62 | ||||

(Please note that the literature values do not correspond to the hydrogen number.) The 1H NMR data shows that the assignments by Paquette are consistent at higher chemical shifts in terms upon inspection of the range covered and the number of atoms they have been assigned to. At the lower end, greater deviations are seen perhaps to the dimethyl protons on the methyl bridge. More information of splitting and spin-spin coupling constants is required to conclude whether the literature has correctly assigned the peaks.

13C NMR calculation of Isomer 18

The technique for comparing the calculated 13C chemical shifts to those in the literature was taken from Braddock and Rzepa's[4] investigation.

| Carbon number | δ /ppm | Δδ /ppm | Spectrum

(Model values - Lit. values) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular model | Literature[2] | |||

| 25 | 22.59 | 19.83 | -2.76 |

|

| 5 | 24.17 | 21.39 | -2.78 | |

| 15 | 24.57 | 22.21 | -2.36 | |

| 24 | 26.51 | 25.35 | -1.16 | |

| 16 | 28.42 | 25.56 | -2.85 | |

| 11 | 32.58 | 30.00 | -2.58 | |

| 22 | 33.72 | 35.47 | 1.75 | |

| 13 | 38.73 | 36.78 | -1.95 | |

| 6 | 41.35 | 38.73 | -2.62 | Deviation of literature values from those calculated |

| 8 | 44.16 | 40.82 | -3.34 |

|

| 9 | 45.80 | 43.28 | -2.52 | |

| 4 | 48.11 | 45.53 | -2.58 | |

| 19 | 49.67 | 50.94 | 1.27 | |

| 14,1 | 55.03 | 51.30 | -3.73 | |

| 2 | 65.94 | 60.53 | -5.41 | |

| 3 | 93.27 | 74.61 | -18.66 | |

| 18 | 120.22 | 120.90 | 0.68 | |

| 17 | 148.01 | 148.72 | 0.71 | |

| 12 | 213.05 | 211.49 | -1.56 | |

The deviation plot of the 13C NMR data shows that the chemical shifts have been assigned relatively closely to those calculated with a mean deviation of around -3 ppm. The experimental value of δ = 74.61 ppm at Carbon-3 is much lower than predicted, caused by the spin-orbit coupling of sulfur to which it is adjacent. No correction value is available at present however considering that for C-Cl it is -3 ppm and -12 ppm for C-Br a value theoretically between the two will not make up for the -18.66 ppm discrepancy.

Analysis of the Properties of Synthesised Alkene Epoxides

Crystal structures of the Shi and Jacobsen catalysts

The Shi catalyst has three anomeric centres. The C-O bond lengths come in pairs of one short, one longer as shown in Table 6. Taking C(10) as an example, C(10)-O(5) bond is shorter than the C(10)-O(4) as the O(5) acts as the electron donating group by lone pair donation into the empty σ* orbital of C(10)-O(4), increasing the bond length. it is most interesting to see O(2) acting as both the electron donating and accepting counterparts of two anomeric centres without much differentiation particularly to C(9). C-O bond lengths at C(2) anomeric centre are much shorter due to the favoured anti-periplanar arrangement of the lone pair and σ* creating a stronger interacting and shorter bond.

| Anomeric centre | Bond length A | Bond length B |

|---|---|---|

| C(9) | 1.423 | 1.454 |

| C(2) | 1.415 | 1.423 |

| C(10) | 1.428 | 1.456 |

The adjacent t-butyl group on the Jacobsen catalyst are arranged in a staggered manner to minimise steric repulsion as they are so close. Its crystal structure suggests a through space separation of 2.421 Â at the shortest contact and 2.975 Â for the longest. The steric bulk not only helps to stabilise the catalyst but increases the enantioselectivity of epoxidation as discovered by Palucki et al[6]

NMR properties of two synthesised epoxides

You can compute the expected 13C and 1H spectra (chemical shifts and coupling constants) of your epoxides to check the integrity of what you have made. The technique for doing this was illustrated for taxol above. This on its own however will not identify the absolute configuration of your product.

(R)-Styrene epoxide

NMR chemical shifts DOI:10042/26679 Spin-spin coupling DOI:10042/26680 gNMR http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=-pn8K53IUqgC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q=gnmr&f=false

| Hydrogen number | δ /ppm | Δδ /ppm | Splitting | Proton count | Spectrum (Click to enlarge) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calculated | Literature[7] | Literature | Calculated | Literature | |||

| 13 | 7.51 | 7.35 | -0.16 | m | 4 | 5 |

|

| 10 | 7.51 | ||||||

| 12 | 7.48 | -0.13 | |||||

| 11 | 7.45 | -0.10 | Deviation of literature values from those calculated | ||||

| 14 | 7.30 | 7.35 | -0.05 | NA | 1 |

| |

| 15 | 3.66 | 3.87 | -0.21 | 1 | |||

| 17 | 2.54 | 3.16 | 0.04 | ||||

| 16 | 2.34 | 2.81 | 0.27 | ||||

| Carbon number | δ /ppm | Δδ /ppm | Proton count | Spectrum (Click to enlarge) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calculated | Literature[7] | Calculated | |||

| 5 | 135.13 | 137.75 | 2.62 | 1 |

|

| 1 | 124.13 | 128.65 | 4.521 | 1 | |

| 3 | 123.41 | 5.24 | 1 | ||

| 4 | 122.96 | 128.33 | 5.37 | 2 | Deviation of literature values from those calculated |

| 2 | 122.95 | 125.65 | 2.70 | 2 |

|

| 6 | 118.27 | 128.33 | 10.06 | 1 | |

| 7 | 54.06 | 52.51 | -1.55 | 1 | |

| 8 | 53.47 | 51.33 | -2.14 | 1 | |

https://www.thieme-connect.de/ejournals/html/10.1055/s-2007-965877 [7] ( R )-Styrene Oxide [( R )-7]

Colorless liquid; yield: 44 mg (37%); 87% ee [chiral GC analysis, chiral capillary column β-Hydrodex PM, 100 °C, isothermal, t R = 14.45 min (major), 15.13 min (minor)].

[α]D 20 +20.3 (c 0.3, CH2Cl2) {Lit. [8b] [α]D 23 +28.6 (neat)}. Schaus SE. Brandes BD. Larrow JF. Tokunada M. Hansen KB. Gould AE. Furrow ME. Jacobsen EN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124: 1307

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 2.81 (dd, J = 5.4, 2.5 Hz, 1 H, PhCHCHH), 3.16 (dd, J = 5.4, 4.0 Hz, 1 H, PhCHCHH), 3.87 (dd, J = 4.0, 2.5 Hz, 1 H, PhCHCH2), 7.30-7.40 (m, 5 H, Ph).

13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 51.33, 52.51, 125.65, 128.33, 128.65, 137.75.

(1S,2R)-1,2-dihydronapthalene oxide

DOI:10042/26641 TMS B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) Chloroform

| Hydrogen number | δ /ppm | Δδ /ppm | Splitting | Proton count | Spectrum (Click to enlarge) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calculated | Literature[8] | Literature | Calculated | Literature | |||

| 15 | 7.62 | 7.44 | -0.18 | d, J = 7 Hz | 1 | 1 |

|

| 12,13 | 7.39 | 7.33-7.21 | -0.12 | m | 2 | 2 | |

| 14 | 7.25 | 7.13 | -0.12 | d, J = 7 Hz | 1 | 1 | |

| 21 | 3.56 | 3.89 | 0.33 | d, J = 4 Hz | 1 | 1 | Deviation of literature values from those calculated |

| 20 | 3.48 | 3.77 | 0.29 | t, J = 4 Hz | 1 | 1 |

|

| 16 | 2.95 | 2.83-2.79 | -0.18 | m | 1 | 1 | |

| 17 | 2.27 | 2.59-2.55 | 0.30 | m | 1 | 1 | |

| 18 | 2.21 | 2.49-2.41 | 0.24 | m | 1 | 1 | |

| 19 | 1.87 | 1.18-1.76 | -0.09 | m | 1 | 1 | |

| Carbon number | δ /ppm | Δδ /ppm | Proton count | Spectrum (Click to enlarge) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calculated | Literature[8] | Calculated | |||

| 4 | 135.39 | 137.1 | 1.71 | 1 |

|

| 5 | 130.37 | 132.9 | 2.53 | 1 | |

| 6 | 126.67 | 129.9 | 3.23 | 1 | |

| 2 | 123.79 | 128.8 | 5.01 | 1 | |

| 3 | 123.53 | 128.8 | 5.27 | 1 | Deviation of literature values from those calculated |

| 1 | 121.74 | 126.5 | 4.76 | 1 |

|

| 9 | 52.82 | 55.5 | 2.68 | 1 | |

| 10 | 52.19 | 53.2 | 1.01 | 1 | |

| 7 | 30.18 | 24.8 | -5.38 | 1 | |

| 8 | 29.06 | 22.2 | -6.86 | 1 | |

Assigning the absolute configuration of two epoxides

Assignment of the absolute configuration of the styrene epoxide and 1,2-dihydronapthalene oxide can be achieved in three different ways:

- investigation of literature

- calculation of chiroptical properties including

- a) Optical Rotatory Dispersion, ORD

- b) Electronic Circular Dichroism, ERD

- c) Vibrational Circular Dichroism, VCD

- calculation of properties of the transition state for the reaction

Chiroptical properties of the product epoxides

a) Optical Rotatory Dispersion, ORD

| Method | [a]25D /° | Wave length /nm | Solvent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanistic Model | -30.40 | 589 | chloroform |

| Experimental[9] | -33.3 | 589 | neat |

The calculated ORD of this enantiomer is very close to that of the literature where 5 have been reported but give different values. Other solvents were used which will affect the rotatory power as the light can be diffracted differently depending on the solvent.

| Method | (1S,2R) | (1R,2S) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [a]25D /° | Wave length /nm | Solvent | [a]25D /° | Wave length /nm | Solvent | |

| Mechanistic Model | 35.86[10] | 589 | chloroform | 155.82[11] | 589 | chloroform |

| Experimental[12] | -38.8 | 589 | chloroform | 152.5 | 589 | chloroform |

The S,R ORD of was calculated to give the opposite rotation of the same magnitude however upon calculation of the R,S, a positive rotation matched that in literature.

c) Vibrational Circular Dichroism, VCD

styrene epoxide DOI:10042/26685 :

1,2-dihydronapthalene oxide DOI:10042/26672 :

Transition state properties of epoxidation

Styrene epoxide

| Energy | Diastereoisomer | |

|---|---|---|

| R | S | |

| G /Hartree/particle | -3343.962162 | -3343.969197 |

| G /kJmol-1 | -8779572.656 | -8779591.127 |

| ΔG /kJmol-1 R-S | 18.471 | |

| K | 1728.973 | |

| ee /% | 99.94 | Lit. 99[13] |

cis-β-methyl styrene epoxide

| Energy | Diastereoisomer | |

|---|---|---|

| R,S | S,R | |

| G /Hartree/particle | -3383.251060 | -3383.259559 |

| G /kJmol-1 | -8882725.658 | -8882747.972 |

| ΔG /kJmol-1 R-S | 22.314 | |

| K | 8155.095287 | |

| ee /% | 99.98 | Lit. 82[13] |

Non-covalent interactions (NCI) in the active-site of the reaction transition state

Transition state in R,R Jacobsen epoxidation of styrene |

Electronic topology (QTAIM) in the active-site of the reaction transition state

Conclusion

It was found that many programs can be used to predict properties of compounds using computer modelling to further understand reactions that we may not have otherwise been able to using other methods. Some still have drawbacks such as the QTAIM analysis only providing quantitative visual analysis however it will be exciting to see future developments leading it to perhaps widespread use.

References

- ↑ W. F. Maier, P. von Rague Schleyer, "Evaluation and Prediction of the Stability of Bridgehead Olefins", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981 103 1891.DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 L. Paquette, N. A. Pegg, D. Toops, G. D. Maynard, R. D. Rogers, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1990, 112, 277-283. DOI:10.1021/ja00157a043

- ↑ Y.Ichinose|DOI:10042/26671

- ↑ C. Braddock and H. S. Rzepa, J. Nat. Prod., 2008, 71, 728-730.DOI:10.1021/np0705918

- ↑ Y.Ichinose|DOI:10042/26671

- ↑ Palucki, M.; Finney, N.S.; Pospisil, P.J.; Güler, M.L.; Ishida, T.; Jacobsen, E.N. "The Mechanistic Basis for Electronic Effects on Enantioselectivity in the (salen)Mn-Catalyzed Epoxidation Reaction," J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 948–954.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Schaus SE. Brandes BD. Larrow JF. Tokunada M. Hansen KB. Gould AE. Furrow ME. Jacobsen EN., J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2002, 124, 1307.DOI:10.1055/s-2007-965877

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 M. W. C. Robinson, A. M. Davies, R. Buckle, I. Mabbett, S. H. Taylor and A. E. Graham*, "Epoxide ring-opening and Meinwald rearrangement reactions of epoxides catalyzed by mesoporous aluminosilicates", Org. Biomol. Chem., 2009, 7, 2559-2564. {{DOI|10.1039/B900719A}

- ↑ F. R. Jensen , R. C. Kiskis, "Stereochemistry and Mechanism of the Photochemical and Thermal Insertion of Oxygen into the Carbon-Cobalt Bond of Alkyl(pyridine)cobaloximesl", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1975, 97 (20), 5825-5831.DOI:10.1021/ja00853a029

- ↑ Y. Ichinose DOI:10042/26689

- ↑ Y. Ichinose DOI:10042/26760

- ↑ L. Hui, L. Yan, Q. Jing, W. Zhong-Liu, L. Hui, Q. Jing, "Styrene monooxygenase from Pseudomonas sp. LQ26 catalyzes the asymmetric epoxidation of both conjugated and unconjugated alkenes", J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzym.,2010, 67 (3-4), 236-241. DOI:10.1016/j.molcatb.2010.08.012

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 S. E. Schaus , B.t D. Brandes , J. F. Larrow, M. Tokunaga , K. B. Hansen , A. E. Gould , M. E. Furrow , and E. N. Jacobsen *, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2002, 124(7), 1307-1315.DOI:10.1021/ja016737l Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "ee styepox" defined multiple times with different content