Rep:Mod:xyzzy

Introductory Exercises

All diagrams in this section taken from this module's wiki page.

Molecular Mechanics

Hydrogenation of cyclopentadiene dimer

Models of the two molecules 1 and 2 were created, and the MM2 mode of calculation used to minimise their energies. It was found that the exo dimer, structure 1, had an energy of approximately 32 kcalmol-1 while the endo dimer, 35 kcalmol-1. Given that the observed product of dimerisation is the higher-energy endo form, it seems reasonable to suggest that this reaction is kinetically controlled, as thermodynamic control would favour the formation of the less energetic state.

A similar treatment of the products of hydrogenation, 3 and 4, gives their energies to be 36 kcalmol-1 and 31 kcalmol-1, respectively. Given that the creation of 3 would involve and increase in energy, the favoured product is probably 4 – from the model it is clear that the planar nature of the double bond ‘flattens’ the curved dimer, moving the carbons at the end further away from each other, and decreasing their interactions. This is reflected in a lower van der Waals energy, calculated by the minimisation program; the ‘bending’ term is also significantly higher in the structure of 3 than in 4, indicating that the molecule’s flexing causes more interactions in this more closed structure.

Stereochemistry of additions to a pyridinium ring

It is found that in structure 5, the carbonyl O is inclined 24° with respect to aromatic ring; sticking up as drawn. Coordination between the carbonyl O and the Grignard Mg atom causes the nucleophile to attack from the top face of the ring; according to Schultz, Flood & Springer[1], the lack of flexibility in the seven-membered ring leads to a situation in which the carbonyl bond cannot be angled below the plane of the aromatic ring – therefore the methyl group cannot be delivered with the opposite stereochemistry. It is indeed not possible to construct a model with a minimum energy corresponding to a carbonyl angled below the ring.

Struc. 7: carbonyl bent to the opposite face of the seven-membered ring than the methyl group – as drawn, below. Angle -21°. Modelling of the product shows a fairly high dipole-dipole interaction, which is consistent with the explanation of Leleu et al[2] that the methyl group interacts with the hydrogen atom on the incoming amine, causing attack on the same face of the ring. Steric control by the carbonyl oxygen is also cited as a reason for this selectivity. These effects can be assumed to be fairly strong ones, as one would expect that some measure of hydrogen bonding between the oxygen and the amine would favour the addition of the amine to the ‘underside’ of the ring. However, this is not what is observed.

Taxol synthesis intermediate

Structure 11, with the oxygen pointing down, was found to be the more stable isomer. When the oxygen is aligned upwards, the molecule deforms in order to reduce the interaction between it and the methyl groups on the bridging carbon, making the whole structure curve to a much greater degree. This increases interactions on the concave face or underside; although there is an energy minimum corresponding to this conformation, it is higher (60 as opposed to 44 kcalmol-1) than the ‘flatter’ conformation in which the oxygen points downwards.

The unreactive nature of the alkene is due to it being a hyperstable alkene. These were first described by Maier and Schleyer[3] in 1981 in terms of ‘olefin strain’, or OS, which they defined as being the extra strain imposed upon a bicyclic system when a bridgehead alkene was introduced – that is, the total bridgehead olefin strain less the strain inherent in the carbon framework. They used this as a measure of alkene stability and found that in certain systems it was possible for OS to be negative; in these cases, the parent saturated compound was more strained than the alkene. This can be attributed to the preference of the carbon atoms involved to be sp2 hybridised. In this structure, use of modelling confirms that hydrogenation of the double bond increases the energy of the system, from 44 to 74 kcalmol-1. This, then, is why this alkene is found to react abnormally slowly.

Room-temperature hydrolysis of a peptide

Structure 13:

- equatorial isomer: 13 kcalmol-1. Given conformation H-bonding is likely between the alcohol and the carbonyl.

- axial isomer: 20 kcalmol-1, less H-bonding.

Neither of these have the NH2 close enough to the OH for any meaningful interactions, tempting though it might be to suppose that this happens.

Structure 14:

- equatorial isomer: 9.6 kcalmol-1. Bicyclic system is less strained, also high possibility of hydrogen bonds between OH and carbonyl O.

- axial isomer: 14 kcalmol-1. Hydrogen bonds still in place.

Axial configuration is, in both cases, less stable probably due to the increase in 1,3-diaxial interactions between H and CH2. However, structure 14 is overall the more favourable of the two, largely due to the greater strain imposed on the more curved bicyclic structure in 13.

It is mentioned by Fernandes et al[4] that ‘In general, intramolecular systems that react with exceptionally fast rates involve relief of steric strain’. When the products of hydrolysis of structure 13 are modelled, a significant decrease in the ‘torsion’ term of the minimization is found, the difference being much greater for the equatorial isomer as the axial forms. This effect is much less striking when the equivalent models are constructed for structure 14 – another reason perhaps for the slower rate of hydrolysis.

Semi-empirical MO Theory

Addition of dichlorocarbene

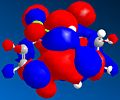

MM2 minimisation of the diene structure gives 17.9 kcalmol-1. Images were generated of the HOMO, LUMO, HOMO-1, LUMO+1, and LUMO+2 orbitals (below) and the required stretching vibrations found:

- Cl-C: 549

- C=C: 1741 anti to Cl; 1761 syn.

-

HOMO

-

HOMO-1

-

LUMO

-

LUMO+1

-

LUMO+2

Minimisation of the monohydrogenated product gives 22.3 kcalmol-1. Images of the same orbitals saved, and the same vibrations found:

- Cl-C: 537

- C=C: 1762 (syn to Cl)

-

HOMO

-

HOMO-1

-

LUMO

-

LUMO+1

-

LUMO+2

Mini-project: Assigning Regioisomers in 'Click Chemistry'

Optimised geometry of the 1,4-isomer |

Optimised geometry of the 1,5-isomer |

Spectroscopic differences: In both 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy, looking at the structure one would expect there to be very few peaks with a clear multiplicity; the molecule is largely constructed of aromatic rings, which give rise to very characteristically ‘messy’ and broad peaks. However, the protons on the CH2 and the one on the triazole ring are not part of systems with such a wealth of couplings, and so they can be expected to give rise to clearly distinguishable peaks. The multiplicity and coupling constants of these peaks could be used to distinguish between the isomers, with the 1,4-isomer displaying a much greater coupling constant between the CH2 proton and the triazole ring hydrogen (while normally it is assumed that coupling over more than three bonds is so weak as to be negligable, when the system involved is as electron-rich as an aromatic triazole ring it seems reasonable to assume that the 5JHHar constant will be noticeable).

Similarly, in 13C NMR, the coupling between the CH2 and the carbon in the 5-positioned phenyl substituent in the 1,5-isomer would likely be much stronger – again, due to physical proximity. There will also be differences in the peaks shown by the two carbons in the triazole ring; unlike those in the benzene rings, these are less likely to give rise to a confusing aromatic peak as the majority of the 5-membered ring is made up of nitrogen (there will probably be satellite peaks but these are unlikely to severely compromise clarity). Therefore, the difference in these peaks (coupling at least, chemical shift is likely to be less affected) between the two isomers should allow them to be distinguished.

There will probably also be noticeable differences in the IR spectra of each isomer; for example, the bending vibrations of the phenyl-triazole bonds may well be of a higher energy in the 1,5-isomer, due to the fact that the substituents are much closer together in this structure and will therefore interact more. However, these differences are almost certain to be more subtle and less useful than the differences between the NMR spectra of the isomers.

The IR spectra were calculated, along with the NMR (the NMR data for the 1,4-isomer can be found at DOI:10042/to-1229 and that for the 1,5 at DOI:10042/to-1230 ), however, though these spectra do display differences, they are not obviously rationalised by reference to the structures. The NMR spectra, however - for both isomers - are very similar to those reported in the supporting information for the original paper by Sharpless et al[5]. In general, both isomers' spectra show a single peak at around 52-54 ppm - probably the CH2 - as well as a much more complex peak, with higher multiplicity and intensity, between 120-130 ppm (which can be assigned to the phenyl rings). The final peaks of any consequence are a series of three between 130-140 ppm in the spectrum of the 1,5-isomer, which is missing from both the calculated and experimental spectra of the 1,4. It could well be that these originate from the carbon atoms in the triazole ring, and in the 1,4-isomer these are sufficiently shifted by interactions with the phenyl substituent to add to the broad region of complex peaks, thus making them difficult to distinguish.

This close agreement between experiment and calculation suggests that both the copper- and ruthenium-catalysed reactions are indeed as regiospecific as assumed, as the experimentally derived spectra do not differ sufficiently from the calculated ones for there to be any non-negligable amount of the alternate regioisomer in the samples. It also provides evidence for the suitability of this method of calculation for this type of fairly simple molecule, lacking any heavy atoms.

The copper-catalysed regioselective reaction to give the 1,4-isomer (structure 16 above) is understood to involve the acidification of a terminal alkyne with the Cu catalyst, which is then easily deprotonated. The catalyst is then attacked by the azide and the product is formed as a result of intramolecular cyclization. This pathway is illustrated to the left (diagram taken from a review of click chemistry by María Victoria Gil, María José Arévalo and Óscar López[6]).

In contrast, the regioselective click reaction that results in the 1,5-isomer (structure 15) is not yet fully understood. In the original paper[5], it was proposed the mechanism illustrated on the right, which proceeds via a six-membered ring of which the ruthenium catalyst is a part, as opposed to a substituent (diagram from the referenced paper).

References:

- ↑ DOI:10.1021/jo00356a016, A. G. Shultz, L. Flood and J. P. Springer, J. Org. Chemistry, 1986, 51, 838.

- ↑ DOI:10.1016/j.tetasy.2004.11.004, Leleu, Stephane; Papamicael, Cyril; Marsais, Francis; Dupas, Georges; Levacher, Vincent. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, 2004, 15, 3919-3928.

- ↑ DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003, Wilhelm F. Maier, Paul Von Rague Schleyer. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103 (8), pp 1891–1900.

- ↑ DOI:10.1021/jo800706y, M. Fernandes, F. Fache, M. Rosen, P.-L. Nguyen, and D. E. Hansen, 'Rapid Cleavage of Unactivated, Unstrained Amide Bonds at Neutral pH', J. Org. Chem., 2008, 73, 6413–6416 ASAP.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 DOI:10.1021/ja054114s, Li Zhang, Xinguo Chen, Peng Xue, Herman H. Y. Sun, Ian D. Williams, K. Barry Sharpless, Valery V. Fokin, and Guochen Jia. 'Ruthenium-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Alkynes and Organic Azides'. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2005, 127 (46), pp 15998–15999

. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "rucat" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ DOI:10.1055/s-2007-966071, Gil, M. V.; Arevalo, M. J.; Lopez, O. 'Click Chemistry - What's in a Name? Triazole Synthesis and Beyond'. Synthesis, 2007, 1589-1620.