Rep:Mod:xl3209module1

Third Year Computational Project-Xizhou Liu

Module 1.1 Modelling using Molecular Mechanics

The Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

The dimerization of cyclopentadiene has been well established in past years. This Diels-Alder ([4+2] cycloaddition) reaction has been reported to have two different isomers: exo-dicyclopentadiene 1 and endo-dicyclopentadiene 2 (The exo and endo isomers are drawn in ChemBio3D as shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2 respectively). Herndon et al. claimed that the endo-isomer is the major product at room temperature.[1] Baldwin further concluded that although the exo-isomer is thermally more stable than the endo-isomer but the kinetic effect dominates at room temperature.[2]

In order to determining the dominant effect of the thermodynamic effect and the kinetic effect, molecular mechanic MM2 force field calculations are performed. These calculations are performed in minimizing the thermodynamic energies of the two different isomers. (Note: the parameters of energies calculated by MM2 are undefined, thus here we can only compare the energies for two different isomers qualitatively.)

As shown in Table 1, the total energy of endo-isomer is higher than the exo-isomer (Difference in toal energy = 2.12 kcal mol-1). This indicates that the exo-isomer is more thermodynamically favourable than the endo-isomer.In other words, if the reaction establishes in equilibrium, the exo-isomer is formed predominately. It is worth to mention that the main contribution to the energy difference arise from the torsional energy (1.86 kcal mol-1). From the measured torsional angle (dihedral angle) shown in Jmols of compound 1 and 2 (178.6o and -47.9o ), the exo-dicyclopentadiene clearly experiences less torsional strain.

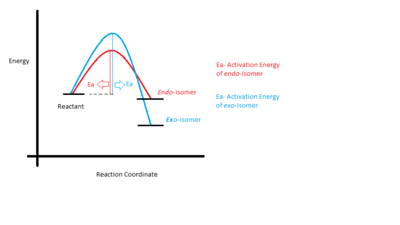

Although the endo-isomer is less thermally stable, it is the major isomer formed. Cycloaddition reactions are normally regarded as reversible reaction, the large gain in stabilization energies in the dimer form leads to essentially irreversible. This indicates that the kinetic effect is the dominant effect: At relatively low temperature and short reaction coordinates, the activation barrier to form endo-dicyclopentadiene is lower than the exo-dicyclopentadiene and therefore the endo-isomer forms faster. The concept is illustrated in Figure 3, as the energy level of the endo-isomer is higher than that of exo-isomer, due to its lower activation energy to surmount the barrier, it is formed faster. Baldwin also indicated that the thermal isomerisation from endo-dicyclopentadiene to exo-dicyclopentadiene takes places at 180-240oC, which supports the discussion of the kinetic control above.[2]

Hydrogenation of endo-dicyclopentadiene

Hydrogenation of of the endo-dicyclopentadiene gives initially one of the dihydro derivatives 3 or 4,(as before, the structures are shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5 accordingly and MM2 calculations are performed. The relative energies of the calculations are shown in Table 2 below.)

According to the calculations, the dihydro derivative 4 is clearly the thermodynamic product. The highest contribution of the difference in relative energies of dihydro derivatives 3 and 4 arises from the bending energy (4.65 kcal mol-1). This may be resulted from the destabilization energy of the hydrogenation of the 5-member ring.

Furthermore, the bending energy can be explained in terms of the bending angles in C-C-C geometry. Generally the angles between the carbons in a butene molecule adopts to sp2 geometry (the C-C-C angle is 120o) as the most stable form and this angle distorts in strained conformations. The angles of dihydro derivatives 3&4 are 107.3o, 107.3o and 113.0o,112.4o accordingly. Therefore the derivative 4 adopts more similar conformations as the sp2 geometry and is the thermodynamically stable product.

The kinetic product cannot be determined unless actual experiments are performed. Although for the endo-isomer 2, the kinetic formation can be explained in terms of frontier orbitals as the LUMOs of the dienophile and the HOMOs of the diene can overlap and resulting in stabilizing the energies. We cannot simply draw any similar conclusions here for the dihydro derivatives as no experimental data such as the transition state energies are available.

Stereochemistry and Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

Atropisomers are stereoisomers where free rotation about a single covalent bond is restricted due to high interconversion barriers (this is often because the steric strain). The different stereoisomers in this case are able to be isolated.[3]

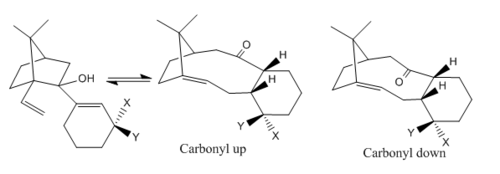

In 1991, Elmore and Paquette proposed a comprehensive report of the first thermally induced Oxy-Cope Rearrangement.[4] The Figure 6 was an example of the reaction schemes which shows the ability of carbinols undergoing atropselective Oxy-Cope Rearrangement, forming two atropisomers or one of them depending on the nature of the substituted groups X and Y.

By inspection of the reaction scheme, the carbinol molecule contains bridgehead cyclic structure, which clearly gives a large steric strain to the whole molecule. The formation of the olefin results in the release of the bi-cyclic strain after removal of the two hydrogen atoms. This renders the forward reaction favourable.

The “olefin strain energy” (OS) is defined as the difference between the strain energy of itself and its parent molecule.[5] This OS energy can thus be used to predict the stability of bridgehead alkenes. Based on the the OS energy, the 'hyperstable' olefin can be defined as the olefin which is more stable and less reactive than its parent molecule.

The unsubstitued atropisomers are the key intermediates in the total synthesis of taxol (drug in treatment of ovarian cancers.) Here, the stereochemistry and relative reactivity of the unsubstitued atropisomers (X=Y=H) with the same structures shown in Figure 6 are studied computationally by two different force-fiels MM2 and MMFF94. The structures of the two different atropisomers, 'carbonyl up' form (intermediate 9) and 'carbonyl down' form (Intermediate 10) are shown in Figure 7 and 8. In fact, these intermediates are not only atropisomers but also hyperstable olefins, which do not undergo hydrogenation under normal conditions.

During the MM2 force field calculations, some ambiguities are encountered. The modified energy of the taxol intermediates somehow have different values. By referring to the second year conformation analysis course, cyclohexane has three conformers, the chair and the two (enantiometric) twist-boats. The chair form is the minimum energy in the energy profile, and the twist boat form is the local energy minimum. Therefore this explains the different energy values encountered before. Only one twist-boat conformer of both intermediates is founded as the other enantiometric twist-boat conformer is the trans-isomer.

| Intermediate 9 Chair | Intermediate 9 Twist boat | Intermediate 10 Chair | Intermediate 10 Twist boat | |

From table 3, the intermediate 10 chair conformer clearly has the lowest energy among the four conformations. It is worth to mention that the torsional energies (ca.20 kcal mol-1) of the taxol intermediates are about doubled comparing to the cyclopentadiene analysed previously (ca.10 kcal mol-1), which indicates the torsional strain are much greater for the taxol intermediates than cyclopentadiene dimers.

Further evidences of the relatives energies between the four conformers are shown in table 4. These energies are calculated from MMFF94 molecular mechanics.MMFF94 methods are generally to be more sophisticated than MM2 methods. MMFF94 methods calculate intermolecular and intramolecular interactions in the electrostatic fashion. While MM2 simply uses Van der Waals equations to interpret the hydrogen bondings.

From both of the calculations by MM2 and MMFF94, similar geometries and trends of the relative energies are obtained. The intermediate 10 chair conformer has the lowest energy among the four conformations and is the thermodynamic product. In other words, the intermediate 9 will undergo isomerisation to give 10 chair conformer under thermodynamic control.

A small discrepancy between the two different molecular mechanics calculations is worth to noted: the energy of intermediate 9 chair conformer is lower than intermediate 10 twist-boat conformer in MM2 calculations, in contradiction to the energies calculated in MMFF94 calculations. Since semi-empirical molecular orbital calculations are made for the later exercises, the MOPAC/PM6 is also performed here. The heat of formation of intermediate 9 chair conformer is calculated to be -51.75 kcal mol-1 and that of intermediate 10 twist-boat conformer is 61.09 kcal mol-1. It seems that MM2 method works better in this case accidentally since a difference less than 5 kcal mol-1 in molecular mechanical calculations are not reliable.

To support the classification of the 'hyperstable olefin' discussed earlier from the literatures, MM2 and MMFF94 calculations are performed for the hydrogenated intermediates 9&10 chair conformers.

As shown in Table 5, the dihydro derivatives of 9&10 calculated energies are both larger than those of the corresponding olefins. This clearly indicates that the presence of the hyperstable olefins. From the definition of olefin strain energy, OS = torsional (olefin) – torsional (hydrogenated) can be calculated. The OS energies in MM2 of intermediate 9&10 are -5.20 and -2.08 kcal mol-1. Note: these values are only for qualitatively analysis only.

Module 1.2 Modelling using Semi-empirical Molecular Orbital Theory

In part 1.1, the weakness of mechanical molecular models are illustrated. In this module, endo-selectivities in Diels-Alder cycloaddition analysed previously are caused by the secondary orbital overlaps. However these orbital overlap are not able to be visualised via the molecular mechanical methods.

In this section, by applying the semi-empirical calculations, such as MOPAC/PM6 or MOPAC/RM1 methods, the effects of the electrons on the molecules, or more precisely the orbital structures are enabled to be visualised. Based on these calculations, spectroscopic properties (i.e. the vibration spectroscopy) can be derived and these properties can be used in analysis of reactivity of many simple molecules.

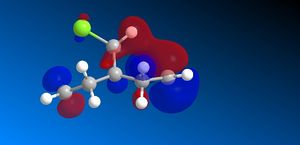

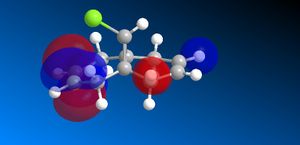

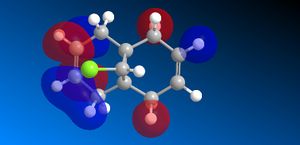

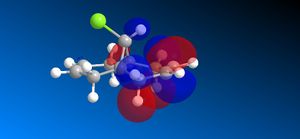

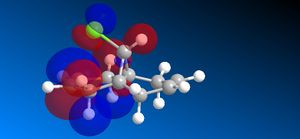

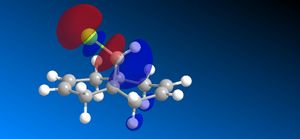

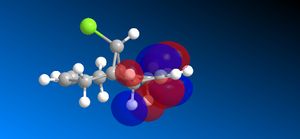

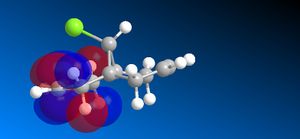

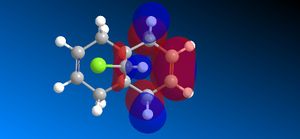

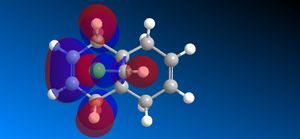

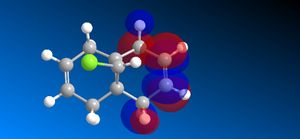

Regioselective Addition of Dichlorocarbene

In 1992, Rzepa et al. reported an extensive study of the structure and regioselectivity of 9-Chloro-1,4,5,8-tetrahydro-4a,8a-methanonaphthalene.[6] It was founded that the naphthalene undergoes regioselective electrophilic addition on the double bond endo/syn to the chlorine substitutent with dichlorocarbene. The environment of the naphthalene is free from steric differentiation, the regioselectivity arises from either orbital or electrostatic control.[7]

Therefore to investigate the regioselectivity of naphthalene further, MM2 was used to pre-optimized the structure of compound 12, followed by performing the MOPAC/PM6 optimization as shown in Table 6.

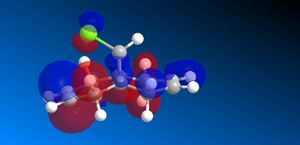

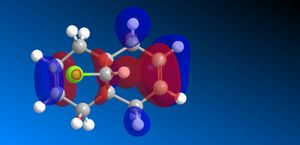

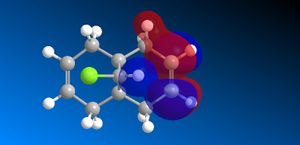

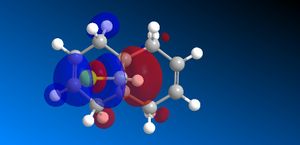

The molecular orbitals (HOMO-1, HOMO, LUMO, LUMO+1, LUMO+2) obtained form PM6 optimization are attached in Table 8. Since the orbitals roughly have a plane of symmetry (the Cl-C-H plane) bisecting the whole molecule. Although orbitals approximately retain the Cs symmetry point group (symmetry point groups: E, σh), the deviations from the Cs symmetry can still be observed from these orbitals generated by PM6 method. Therefore three calculations are done based on PM6, RM1, RM3 to obtain a better approximation of the molecule. In order to decide which calculations are better, the distances between the bridgehead carbon and olefin carbon are measured and compared to literature (from X-ray crystallography).

Although the deviations in symmetry of the PM6 model, it gives the closest optimized structure (in terms of atomic distances) compared to literature among the three models. While RM1 model gives better orbital in visualisation, it is not so good at producing the optimized structure. Finally the PM3 model seems to give quite different values from literature and other two models. Thus, the molecular orbitals of the compound 12 of PM6 and RM1 models are discussed further. (Mopac/RM1 Heat of formation of Compound 12: 22.83 kcal/mol)

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

| ||

Molecular Orbital Analysis:

PM6 model:

- The general trend: across the table, from HOMO-1 orbitals to the LUMO+2 orbitals, more nodal planes appear in the orbitals, less bonding interactions, more anti-bonding interactions.

- In HOMO-1 molecular orbitals, both olefin experience bonding interactions, however electron density locates more around the bonding πC=C orbitals exo to the C-Cl bond.

- In HOMO molecular orbitals, electron density locates more around the bonding πC=C orbitals endo to the C-Cl bond. This is a good indication that the endo olefin is more electron-rich and more nucleophilic compared to that of the exo olefin. This indicates that the endo olefin reacts with electrophile better (i.e. dichlorocarbene). Also πC=C orbitals tend to have larger lobes and more diffused, which reacts with electrophile easier.

- In LUMO molecular orbitals, the exo olefin experiences large anti-bonding π*C=C interactions.

- In LUMO+1 molecular orbitals, the anti-bonding σ*C-Cl orbital appears.

- In LUMO+2 molecular orbitals, the endo olefin experiences large anti-bonding π*C=C interactions.

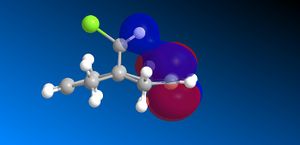

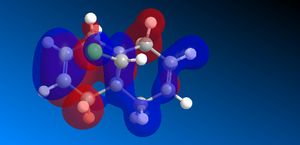

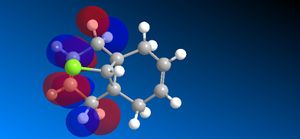

RM1 model (comparing and contrasting):

- In HOMO-1 molecular orbitals, almost only exo olefin experiences bonding interactions, electron density locates around the bonding πC=C orbitals exo to the C-Cl bond.

- In HOMO molecular orbitals, electron density locates mostly around the bonding πC=C orbitals endo to the C-Cl bond. Again, this provides evidence that the endo alkene bonds is more nucleophilic of the two.

- In LUMO molecular orbitals, the significant contrast occurs in the RM1 model compared to the PM6 model,the anti-bonding σ*C-Cl orbitals are observed instead of exo olefin with large anti-bonding π*C=C interactions.

- In LUMO+1 molecular orbitals, the significant contrast appears as the anti-bonding π*C=C interactions are observed instead of the anti-bonding σ*C-Cl orbital appears.

- In LUMO+2 molecular orbitals, the endo olefin experiences mostly anti-bonding π*C=C interactions.

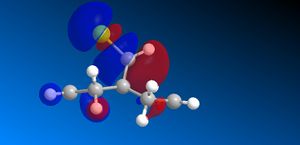

Conclusions:

- HOMO-1, HOMO, LUMO+2 molecular orbitals predicted by the two models agree to each other in large extent. MOs of RM1 model can be treated as an exaggerated form of the PM6 model.

- The anti-bonding σ*C-Cl orbital appears in the LUMO calculated by RM1 method, if this is the case, the antiperiplanar interactions (between the anti-bonding σ*C-Cl orbital in the LUMO and the bonding πC=C exo orbital) can stabilise the HOMO effectively. This will render the endo double bond more nucleophilic in both frontier orbital and electrostatic views.

- The reality might lie in between the two models, if this is the case, the stabilising antiperiplanar interaction becomes weaker and the endo-isomer becomes less selective.

- A last point is of course if time allowed, Gaussian is a much more powerful tool in analysing molecular orbitals compared to Mopac.

Vibrational spectrum prediction:

Monosaccharide Chemistry: Glycosidation

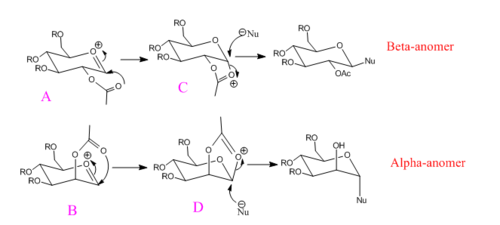

Glycosidation was reported to produce almost 1,2-trans product (also known as the beta-anomer)[9] with both the nucleophile and the OAc group in the equatorial position. The Beta-anomer is mostly the dominant product of the glycosidation due to the neighbouring group effect. The two reaction schemes are shown in Fig 22: the positioning of the OAc groups resulting two different reaction pathways.

To investigate the effect of the positioning of the acyl group around the oxonium ion, MM2 and Mopac/PM6 models are used. The energies of the A, B, C, D are listed in Table 10 including the ring flipped isomers A*, B*, C*, D*.

Methyl group is chosen to used as the R-group in this experiment, as smaller R groups simply takes less time to model while keeping the necessary geometry. Hydrogen is not used as it is not a protecting group (loss of anomeric effect) and the hydrogen bonding interactions. The Mopac/PM6 is a better method than MM2, simply because the MM2 model can only deal with classical cations, while the oxonium here is non-classical cation. Furthermore, MM2 is inadequate to model the interactions between the oxonium oxygen and the lone pairs in the OAc protecting group.

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

From Table 10, it can be seen that A, B, C, D all have smaller energies than their corresponding ring flipped isomers (only considering the Mopa/PM6 model here as it is more accurate). They are more stable than their isomers can be explained as the stabilising interactions between the orbital of the carbonyl oxygen and the oxonium oxygen. The further away the carbonyl oxygen from the six-member ring, the less the stabilising effects.

By comparing the energies, it is not difficult to see that the energies of the A and C, B and D pairs are effectively the same for the Mopac/PM6 model. This suggests that this model is capable of calculating the bonding interactions when the oxygen of the OAc group close to the oxonium carbon. While MM2 is not capable to do that. This supports our discussion at the beginning and indicates that quantum mechanical approach can be used to investigate the bond forming and breaking process.

By looking at the angles of attack, A and B are having similar angles to the famous Burgi-Dunitz angle, where it is the angle that fully defined the geometries when molecules approaching together and collide. In glycosidation, this angle is defined as the angle that the lone pair of electrons of the oxygen (HOMO of nucleophile) of the OAc group attacking the LUMO of the carbonyl of the oxonium group.

Module 1.3 Structure Base Mini Project using DFT-based Molecular Orbital Methods

Selectivity Control in Alkylidene Carbene-Mediated C-H Insertion and Allene Formation

Introduction:

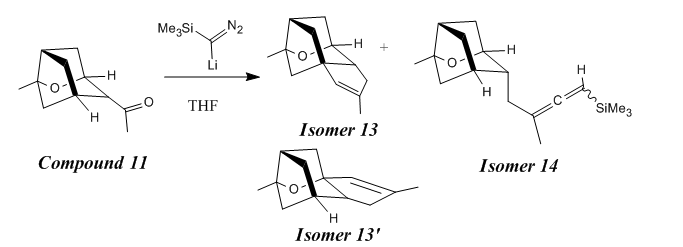

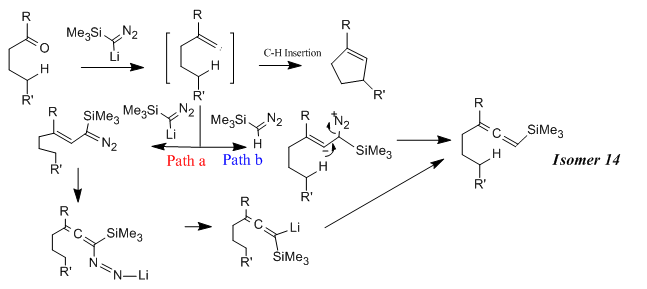

Alkylidene carbenes are widely used as intermediates in many organic synthesis. The strong electrophilic nature of alkylidene carbenes renders their high reactivity. Lee et al. reported that alkylidene intermediates can undergo C-H insertion, [1+2]-cycloaddition and Fritsch-Buttenberg-Wiechell rearrangement. Among many reactions, the C-H insertion reaction gained most attention as its unique feature to generate stereoselective or chemoselective heterocyclic systems. The reaction scheme is shown in Figure 23 and the corresponding mechanism in Figure 24.[8]

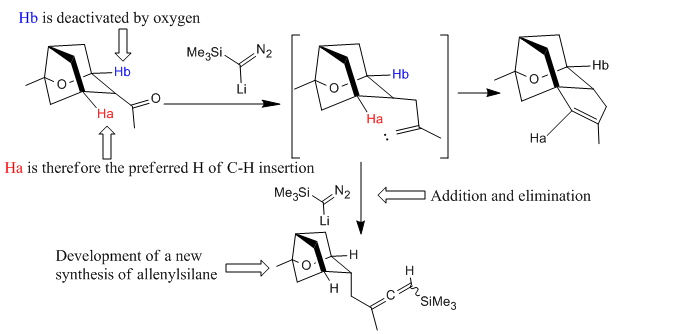

Why is compound 13 the preferred conformation before the allenylsilane formation since the existence of two C-H groups available for the insertion reaction with the carbene?(Figure 25)

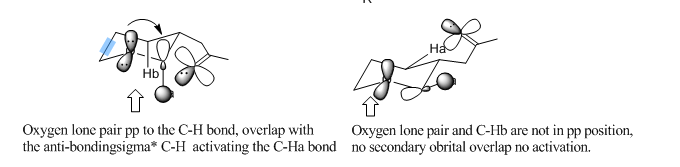

Under the condition of TMSCHN2 (3 equiv), nBuLi (2 equiv), -78oC, the reaction was under thermodynamic control. The main dominant effect here is the steroelectronic effect raised from the hetro-substituted O atom and conformationally constrained system. (illustrated in Figure 26)

This can be further proved by performing the Mopac/PM6 calculations of the compound 13 and compound 13', the relative energies are: -45.57 kcal mol-1, -41.84 kcal mol-1. Therefore the compound 13 has a energy of 3.73 kcal mole-1 less than compound 13'.

Conformational Analysis of isomers 13

and 14.(Note: the Jmol button here displayed the structure optimized by Gaussian DFT, 6-31G(d,p), also the labeled atom numbers also included)

From Table 11, we can see that from both molecular mechanical and semi-empirical calculations, isomer 14 has a much lower relative energy compared to isomer 13 and therefore it is the thermodynamic product. This agrees to the literature, as isomer 14 is by far the major isomer.

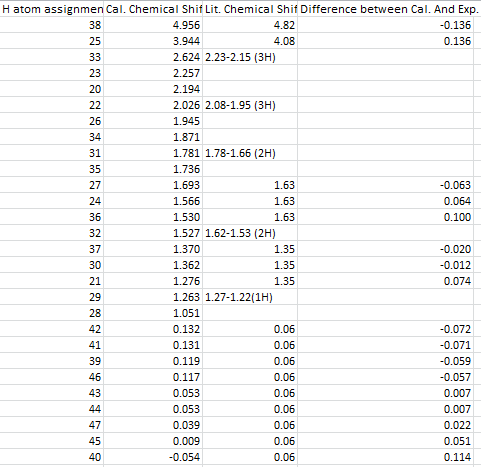

NMR Analysis of Compound 13 and 14 calculated using the GIAO method NMR is by far the most powerful spectroscopically technique to investigate the differentiate between the to chemoselective isomers since the different chemical environment induced by the addition of the silane group. Here 13C and 1H NMR spectra are used, although 17O NMR can be obtained, they are quite rare in literature reports to compare with.

| Table 12. 13C NMR of compound 13 (atom 9 is O) chemical shift in ppmDOI:10042/to-12814 | ||||

| Table 13. 1H NMR of compound 13 chemical shift in ppmDOI:10042/to-12814 | |||||

| 27 | 5.33 | 5.76 | 0.43 | H-C=C | |

| 19 | 4.5 | 4.39 | 4.36 | -0.03 | H-O |

| 29 | 16.5 | 2.30 | 2.46 | 0.16 | H-C-C=C |

| 15 | 6.5 | 2.25 | 2.22 | -0.03 | Bridgehead cyclic system |

| 20 | 1.98-1.90 | 1.88 | N/A | Bridgehead cyclic system | |

| 28 | 1.98-1.90 | 1.87 | N/A | H-C-C=C | |

| 25 | 1.86-1.76 | 1.85 | N/A | Bridgehead cyclic system | |

| 30 | 1.86-1.76 | 1.84 | N/A | Terminal H-C-C=C | |

| 18 | 1.72 | 1.73 | 0.01 | Bridgehead cyclic system | |

| 17 | 1.72 | 1.72 | 0.00 | Bridgehead cyclic system | |

| 32 | 1.72 | 1.67 | -0.05 | Terminal H-C-C=C | |

| 31 | 11.0 | 1.69 | 1.61 | -0.08 | Terminal H-C-C=C |

| 21 | 11.0 | 1.69 | 1.61 | -0.08 | Bridgehead cyclic system |

| 16 | 1.44 | 1.51 | 0.07 | Bridgehead cyclic system | |

| 26 | 1.37 | 1.42 | 0.05 | Bridgehead cyclic system | |

| 24 | 1.34 | 1.33 | -0.01 | Methyl group | |

| 23 | 1.34 | 1.27 | -0.07 | Methyl group | |

| 22 | 1.34 | 1.05 | -0.29 | Methyl group | |

| Table 14. 13C NMR of compound 14 (atom 9 is O, 16 is Si) chemical shift in ppmDOI:10042/to-12816 | ||||

Conclusions:

The distinct difference between the two isomers can be seen from the two 13C NMR chemical shifts easily, Compound 14 has its clear feature of the three MeSci carbons present in the region around zero, also it can be noticed that the quaternary carbon group in compound 14 has its distinct high chemical shift at 205 ppm. Generally the chemical shifts of the allenylsilane are lower than those of isomer 13 due to the presence of the Si group. It is worth to mention that we can also observe the 16Si spectrum of the compound 14 as well.

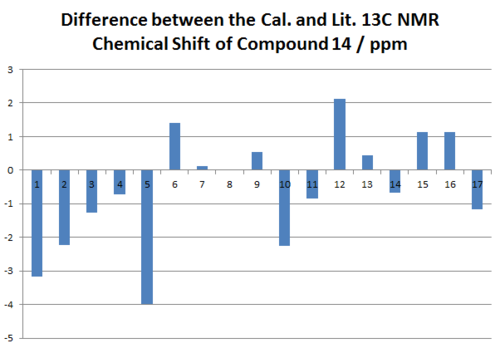

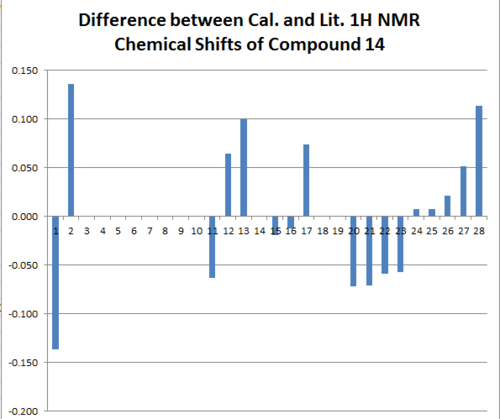

The Chemical shifts of both isomers are compared to literature report, and they agree to the literature to large extent. This might be because of the lack of ionic contributions in both molecules that can distort the NMR prediction largely. As shown in the difference bar charts in Figure 25, 26, 27 and 28 that the difference between the experimental literature and the calculated chemical shifts of 13C NMR spectra are both within the range of 5 ppm. Although the calculated 1H NMR chemical shifts are less in terms of numerical numbers, by taken account of the resolutions of the 13C and 1H NMR spectra, 1H NMR spectra produces less reliable results. Clearly from all of the bar chats, we cannot observe any repeated errors exist in the NMR spectra, which suggests the presence of the systematic error is small. However the discrepancy between the calculated chemical shift and the actual chemical shift seems to be relative large for either very large or very small chemical shifts. In order to minimizing the systematic error, other basis sets can be used if time allowed.

References

1. W. C. Herndon, C. R. Grayson, J. M. Manion, J. Org. Chem., 1967, 32 (3), 526–529 DOI:10.1021/jo01278a003

2. J. E. Baldwin, J. Org. Chem., 1966, 31, 2441

3. P. Lloyd-Williams, E. Giralt, Chem. Soc. Rev., 2001, 30, 145

4. S. W. Elmore and L. Paquette, Tetrahedron Letters, 1991, 319; DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0

5. First paper formally recognizing the new class of "hyperstable" olefins (Wilhelm F. Maier, Paul Von Rague Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103, 1891. DOI: 10.1021/ja00398a003

6. B. Halton, R. Boese and H. S. Rzepa., J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 2, 1992, 447. DOI:10.1039/P29920000447

7. H. R. Rzepa, M. L. Webb, A. M. Z. Slawin and D. J. Williams, J. Chem. Soc, Chem, Commun., 1991, 765.

8. J. C. Zheng, S. Y. Yun., J. Chem. Soc., 20010, 1086

9. D. M. Whitfield, T. Nukada, Carbohydr. Res., 2007, 324, 1291. DOI: 10.1016/j.carres.2007.03.030