Rep:Mod:wyc08

Module 1: The basic techniques of molecular mechanics and semi-empirical molecular orbital methods for structural and spectroscopic evaluations

Objectives

To illustrate some of the diversity of molecular modelling, a selection of modelling experiments are conducted. In this module, we are particularly interested in:

- The prediction of the geometry and regioselectivity of various reactions

- The use of semi-empirical and DFT molecular orbital theory

- The use of institutional digital repository

The last section of this module involves research of reaction with the formation of isomer products. Molecular modelling allows rationalisation of spectroscopic results including 13C NMR, IR and even mass spectrometry.

Modelling using Molecular Mechanics

Molecular Modelling serves as a powerful tool to not only help rationalising outcomes of reactions, but also to predict useful modifications or even new types of reaction. Generally speaking, molecular mechanics is a method of 3D molecular modelling which optimises molecular geometry to an energy minimum, as well as analysing the vibrational and bonding contributions to the total energy. In the following illustrations, Allinger's MM2 force field is employed in ChemBio3D, alongside MMFF94 and Gaussian for the DFT methods. (Choice of program and force field is case dependent.)

The Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

Dimerisation of Cyclopentadiene

At room temperature, cyclopentadiene readily dimerises and in which the endo dimer 2 is produced more specifically relative to the exo dimer 1.

Mechanistically speaking, dimerisation of cyclopentadiene is a concerted [4+2] cycloaddition and is one of the most classical Diels-Alder reactions. Resultant stereoselection in product is predicted by Alder and Stein[1]: Firstly, The stereochemistry of substituents in the starting material is retained. That is, a cis-dienophile reacts in a way that the cis-substituents end up being on the same face of the product while substituents will be on different side if a trans-dienophile is reacted. Secondly, the endo-addition rule, also known as the 'principle of the maximum accumulation of unsaturated centres', is followed. It is important to note that the word endo and exo describe the orientation of substituents in transition states but NOT in the product molecules.

To investigate the stereoselection particularly in the dimerisation of cyclopentadiene, total energy of both exo and endo dimer are calculated, firstly through geometrical optimisation in ChemBio3D, followed by the MM2 force field option. Below table shows the corresponding results:

(For 1 kcalmol-1 = 4.18400 kJmol-1)

| Type of Energy | Exo- Dimer 1 | Endo- Dimer 2 | ||

| Energy/kcalmol-1 | Energy/kJmol-1 | Energy/kcalmol-1 | Energy/kJmol-1 | |

| Stretch | 1.279 | 5.351 | 1.249 | 5.226 |

| Bend | 20.603 | 86.203 | 20.840 | 87.195 |

| Stretch-Bend | -0.837 | -3.502 | -0.833 | -3.485 |

| Torsion | 7.640 | 31.966 | 9.508 | 39.781 |

| Non-1,4-VdW | -1.413 | -5.912 | -1.518 | -6.351 |

| 1,4-VdW | 4.238 | 17.732 | 4.313 | 18.046 |

| Dipole/Dipole | 0.377 | 1.577 | 0.446 | 1.866 |

| Total Energy | 31.886 | 133.411 | 34.005 | 142.277 |

From the resultant calculations, it can be seen that the endo-dimer is of a higher energy than the exo-dimer. Knowing that the endo-dimer is in fact the major product, it can be inferred that the reaction at room temperature is indeed kinetically controlled (and hence irreversible). We would therefore also expect the corresponding transition state of the endo-dimer being at a lower energy than that of the endo-dimer. To explain the difference in energy of the two dimers, we could look into energy contributions from various components. For both dimer, 'Bend' appears to be the major contributor to the total energy of dimers, meaning that there is a considerable deviation from the optimum bond angles of products. Such deviations result from steric interactions experienced by the product molecules, but with the endo-dimer experiencing a greater steric interactions (Difference in 'Bend' energy of endo- and exo-dimer = 0.992kJmol-1). In the respect of stability, the 'torsion' component serves as an excellent indication (Difference in 'Torsion' energy of endo- and exo-dimer = 7.815kJmol-1). This difference in energy is best explained by an unfavourable interaction between the bridged methyl group and the two hydrogens which are on the same face in the endo-product; while such an interaction is not found in the case of exo-dimer.

To complete the picture of this kinetically controlled reaction, the transition state structures of both endo- and exo- dimer have to be considered. Introduced by Woodward and Hoffmann (WH), Secondary Orbital Interactions (SOIs) provides an excellent account for the stabilisation of the endo- transition state (see below figure).

The endo- TS (II) of cyclopentadiene dimerisation clearly benefits from the secondary orbital interactions which is not seen in the case of exo- TS (I). Although there will be steric repulsion between the methylene group and the exo hydrogens, such attractive secondary interactions are significant in an extent to assist the endo- approach, giving the endo-dimer as the major product. Also, the endo-TS is arranged in such a fashion that allows the 'maximum accumulation of unsaturated centres', as depicted by the endo rule.

Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

Now we are in a position to look at the hydrogenation product of the dimer. Hydrogenation proceeds to give initially one of the dihydro derivatives 3 or 4. Only after prolonged hydrogenation results in the tetrahydro derivative. Here, we will focus on the investigation on relative stabilities of 3 and 4. Using the same optimisation technique described above, resultant calculations are tabulated as shown:

| Contributions of Energy | Dihydro derivative 3 | Dihydro derivative 4 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Energy/kcalmol-1 | Energy/kJmol-1 | Energy/kcalmol-1 | Energy/kJmol-1 | ||||||

| Stretching (Str) | 1.254 | 5.247 | 1.099 | 4.598 | |||||

| Bending (Bnd) | 19.762 | 82.684 | 14.548 | 60.869 | |||||

| Stretch-Bend (Str-Bnd) | -0.827 | -3.982 | -0.546 | 2.628 | |||||

| Torsion (Tor) | 10.871 | 45.484 | 12.501 | 52.304 | |||||

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.185 | -5.704 | -1.090 | -5.247 | |||||

| Van der Waals(VdW) | 5.655 | 23.661 | 4.502 | 18.836 | |||||

| Dipole/Dipole | 0.162 | 0.678 | 0.141 | 0.590 | |||||

| Total Energy | 35.691 | 149.331 | 31.156 | 130.357 |

From the calculations obtained, it can be seen that dihydro derivative 4 is of a lower energy compared to that of derivative 3. That is, the dihydro derivative 4 is the thermodynamic product while dihydro derivative 3 is the kinetic product. In terms of energy contributing components, they both gain similar contributions from 'stretch', 'torsion' and 'dipole/dipole' energies while the 'Bending' and 'Van der Waals (VdW)' energies of derivative 4 are considerably lower when compared to that of derivative 3. This could be rationalised by looking at steric interactions in these molecules. The lower stretch and van der Waals energies of 4 indicates a smaller steric interactions in molecule. A lower 'Bending' energy on the other hand, indicates a smaller ring strain in 4. This key difference in ring strain originates from the strength of C=C double bond as well as the deviations of bond angles (from ideal bond angles for a sp2 centres) in the two derivatives. The higher the bending energy, the greater the deviation. In 3, the C=C double bond is in the norbornene unit while that in 4 is in the cyclopentene unit. Double bond in the norbornene unit is slightly longer than that in cyclopentadiene[2]. It is hence weaker and more susceptible to hydrogenation to give 4, at the same time leading to a relief of ring strain. Overall, the dihydro derivative 4 is of lower energy and is thermodynamically more favourable. Preference for the formation of 4 is further supported by the work of D. Skála and J. Hanika [3]. They found that 4 instead of 3 is formed exclusively before prolonged hydrogenation.

It is important to understand that the lowest energy product could be formed under thermodynamically or kinetically controlled reaction. Alkene hydrogenations are usually carried out using a metal catalyst and gaseous hydrogen. Under these conditions, we expect the reaction to be kinetically controlled. Therefore, for the hydrogenation of 2, a thermodynamic product 4 is produced under kinetic control.

Stereochemistry of Nuleophilic Additions to a Pyridinium Ring (NAD+ Analouge)

Alkylation of N-methyl pyridoxazepinone

Optically active derivative of prolinol 5 reacts with methyl magnesium iodide to alkylate the pyridine ring at 4-position. Not only it is regio-selective, but also stereoselective with respect to the addition of methyl group (shown in 6). Using ChemBio3D, a model of the pyridinium reactant is constructed. And through optimisation and MM2 force field calculations, we hope to gain insight in the resultant stereochemistry. However, for 5, the MeMgI component is not included in calculations since the MM2 force field used does not have parameters defined for the Mg atom.

Suggested by Shultz et al [4], addition of Grignard reagents to 5 will result in coordination between the Grignard reagent (effectively the Mg atom) and the amide oxygen, followed by delivery of the methyl ligand to carbon (position-4). To account for the regio- and stereoselectivity, a 'chelation' control is proposed: Coordination between the electropositive Magnesium and the electronegative oxygen (of the amide group) results in the formation of a stable six-membered ring transition state. Methyl group then attacks from the top face of the adjacent carbon, resulting in the observed absolute stereochemistry of reaction. Below figure shows corresponding mechanism of the reaction.

Using the MM2 force field, energies of various conformations of 5 are obtained. In particular, discussion will be focused on the geometry of the carbonyl group and its orientation with respect to the aromatic ring. Quantitatively speaking, we are looking at dihedral angle values between the carbonyl oxygen and the carbon on the adjacent ring (the one which is to be alkylated). Table 3 shows calculations obtained from ChemBio3D.

| Contributions of Energy | Conformer I | Conformer II | Conformer III | |||

| Energy/kcalmol-1 | Energy/kJmol-1 | Energy/kcalmol-1 | Energy/kJmol-1 | Energy/kcalmol-1 | Energy/kJmol-1 | |

| Stretching (Str) | 2.043 | 8.548 | 1.274 | 5.330 | 1.375 | 5.753 |

| Bending (Bnd) | 14.236 | 59.563 | 6.991 | 29.250 | 7.368 | 35.470 |

| Stretch-Bend (Str-Bnd) | 0.132 | 0.552 | 0.114 | 0.477 | 0.115 | 0.481 |

| Torsion (Tor) | 5.087 | 21.284 | 24.522 | 102.600 | 32.965 | 137.926 |

| Non-1,4 VDW (Str) | -0.556 | -2.326 | -2.604 | -10.895 | -2.864 | -13.787 |

| 1,4 Van der Waals(VdW) | 16.545 | 69.224 | 15.324 | 64.116 | 15.224 | 73.288 |

| Charge/Dipole | 9.631 | 40.296 | 10.642 | 51.231 | 10.184 | 49.026 |

| Dipole/Dipole | -3.993 | 16.707 | -3.696 | -17.793 | -3.521 | 16.950 |

| Total Energy | 43.124 | 180.431 | 52.566 | 253.053 | 60.846 | 292.913 |

| dihedral angle | +10.72° | - | +59.95° | - | +79.95° | - |

| Conformer I (Lowest energy conoformer) | Conformer II | Conformer III | |||||||||

|

|

|

It is found that the optimum conformation of 5 is conformer I. It has a total energy of 43.124kcalmol-1, corresponding to a dihedral angle of 10.72o, i.e. C=O double bond lies 10.72o above the ring. 'Bend' and '1,4 Van der Waals' energies contribute mainly to the total energy of this conformer. This indicates quite a large deviations from the ideal bond lengths and intermolecular forces within the molecule. The above table shows conformers with different dihedral angles, together with their energy. In general, the larger the dihedral angle, the higher is the energy of the conformer. Energy also increases when having carbonyl below the plane of the ring. We thus expect conformer I to be the dominating conformer of 5 and hence resulting in the product with stereochemistry exhibited in 6.

Reaction of N-methyl Quinolinium Salt with Aniline

Another similar example to be considered here is shown below. Here, the pyridinium ring of 7 reacts with aniline to form 8 (Mechanism is shown below). Although both reactions are nucleophilic addition, a key difference here is the choice of nucleophile. When PhNH2 attacks 7, the lone pair on nitrogen repels those on the oxygen of the carbonyl group. To minimise such repulsion, the nucleophile attacks opposite face to the carbonyl group. To justify this stereoselection, we again use the MM2 force field to try and find the lowest energy conformer of the reactant 7.

| Contributions of Energy | Conformer IV | Conformer V | Conformer VI | |||

| Energy/kcalmol-1 | Energy/kJmol-1 | Energy/kcalmol-1 | Energy/kJmol-1 | Energy/kcalmol-1 | Energy/kJmol-1 | |

| Stretching (Str) | 3.764 | 16.108 | 3.907 | 18.808 | 3.561 | 17.143 |

| Bending (Bnd) | 11.466 | 54.957 | 12.292 | 59.174 | 10.641 | 51.226 |

| Stretch-Bend (Str-Bnd) | 0.401 | 1.816 | 0.416 | 2.003 | 0.375 | 1.805 |

| Torsion (Tor) | 9.797 | 44.455 | 8.774 | 42.238 | 12.564 | 60.483 |

| Non-1,4 VDW (Str) | 3.435 | 18.857 | 3.810 | 18.341 | 2.697 | 12.983 |

| 1,4 Van der Waals(VdW) | 29.400 | 122.20 | 29.552 | 142.263 | 29.172 | 140.434 |

| Charge/Dipole | 3.308 | 14.682 | 3.332 | 16.040 | 3.266 | 15.723 |

| Dipole/Dipole | -4.889 | -20.389 | -4.897 | -23.574 | -4.883 | -23.507 |

| Total Energy | 56.682 | 252.684 | 57.186 | 275.293 | 57.392 | 276.285 |

| dihedral angle | -19.15° | - | -10.01° | - | -29.98° | - |

From data obtained, conformer IV is found to be the most stable and hence is the equilibrium conformer of 7. Having a total energy of 252.684kJmol-1, it has a dihedral angle of O=C-C-C-H -19.15°; negative sign means that the C=O is on the bottom face of the plane of naphthalene ring. We would thus expect the nucleophile to attack from the opposite face, i.e. top face of the ring. This shows consistency with suggested mechanism. For other conformers having either a larger/smaller dihedral angles (V and VI), they were calculated to be at a higher energy compared to conformer IV. This shows that conformer is the dominating form of 7 with its energy at minimum. Its reaction with PhNH2 to give stereoselective 8 can hence be rationalised by the geometry of attack explained in the mechanism above.

Instead of the MM2 model, MOPAC method can be used in order to improve the reliability and accuracy of results. The MOPAC molecular orbital method introduces molecular orbitals and take into account electronic structure into calculations. This allows better optimisation and gives more accurate energy values.

| Conformer IV (Lowest energy conoformer) | |||

|

Stereochemistry and Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

The synthesis of Taxol serves as an example to explore atropisomerism. Atropisomerism arises when one or more conformer of a molecule cannot be distinguished because of the prevented rotation about single bonds due to steric hindrance. Paquette et al showed that, the key intermediate in the synthesis of Taxol, 9/10, are atropisomers with the carbonyl group pointing either up or down. C=O is restricted to rotation across the ring mainly due to ring size and electrostatic repulsion within this crowded electron density.

Of course we could calculate the energies of the two intermediates through optimisation by MM2 force field. Results show that the twist boat conformation is thermodynamically more stable than the chair conformation. Also, intermediate 10 is thermodynamically more stable than intermediate 9.

| Contributions of Energy | Intermediate 9 in chair conformation | Intermediate 9 in twisted boat conformation | Intermediate 10 in chair conformation (higher energy chair conformation) | Intermediate 10 in twisted boat conformation |

| Energy/kcalmol-1 | Energy/kcalmol-1 | Energy/kcalmol-1 | Energy/kcalmol-1 | |

| Stretching (Str)(from MM2) | 2.668 | 2.825 | 2.559 (3.091) | 2.667 |

| Bending (Bnd)(from MM2) | 15.902 | 16.465 | 10.718 (15.334) | 11.272 |

| Stretch-Bend (Str-Bnd)(from MM2) | 0.396 | 0.460 | 0.328 (0.372) | 0.308 |

| Torsion (Tor)(from MM2) | 18.233 | 21.343 | 19.570 (20.714) | 21.678 |

| Non-1,4 VDW (Str)(from MM2) | -1.151 | -0.971 | -1.227 (0.026) | -1.147 |

| 1,4 Van der Waals(VdW)(from MM2) | 12.689 | 14.091 | 12.541 (13.567) | 13.587 |

| Dipole/Dipole(from MM2) | 0.146 | 0.137 | -0.183(-0.031) | -0.194 |

| Total Energy (from MM2) | 48.883 | 54.350 | 44.306 (53.072) | 48.172 |

| Total Energy (from MMFF94) | 70.541 | 76.301 | 60.591 (74.906) | 66.354 |

Apart from the orientation of carbonyl group in the isomers 9 and 10, it should be noticed that chair or twist boat conformers would arise from each of them, due to the 6-member ring. Taking into account of this, calculations were done through the MM2 force field option and results obtained were tabulated as above. For isomer 9, the chair conformation is of a lower energy and hence more favoured. For isomer 10, there are 2 possible chair conformation. The lower energy chair conformer is of the lowest energy followed by the twist boat conformer, and twist boat conformer is of the highest energy. Overall, energy of isomer 10 is lower than that of 9 and is more thermodynamically favoured. Major contributions of energy are subjected to 'Bending', 'Torsion' and '1,4-van der waals' energies. This could easily be rationalised as for example, a twist boat conformer is formed from a chair conformer in the expense of torsion energy. Also, energy of a conformer again depends on the deviations of bond angles, which is reflected in the 1,4 van der waals energies. In conclusion, we expect a favourable formation of 10 over 9.

To reconfirm that 10 is a more stable isomer, MMFF94 minimisation is employed. As shown in table, 10 is of a lower energy (difference = ~10 kcal/mol). Therefore, from a thermodynamic prospective, on standing, 9 is to atropisomerise to molecule 10. Apart from the concept of atropisomerism, isomers 9 and 10 serves as examples of hyperstable alkene (olefins). Hyperstable alkenes refer to alkenes which are generally constrained in a trans-cycloalkene unit with a least 8 carbon atoms in a bridgehead style. And due to their bridgehead positions, they are comparatively more stable (compared to parent hydrocarbon). Such a property is denoted by a negative olefin strain value. Their extraordinary stability could be explained by having cage structures. This makes them very unreactive and becomes less susceptible to hydrogenation. They are hence more thermodynamically stable and favoured than other possible forms[5].

| 9 chair conformation | 9 twist-boat conformation | 10 lower energy chair conformation | 10 higher energy chair conformation | 10 twist-boat conformation | |||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

Modelling using Semi-empirical Molecular Orbital Theory

The downside of purely mechanical molecular model is that it does not take into account electronic aspects of reactivity, for example, the 'secondary orbital' interactions in Diels Alder cycloadditions described above. To overcome such problem, we introduce modelling using semi-empirical molecular orbital theory.

Regioselective Addition of Dichlorocarbene

Orbital control of reactivity is illustrated below by the molecule 12, 9-chloro-1,4,5,8-tetrahydro-4a,8a-methanonaphthalene. First, we perform optimisation in ChemBio3D by choosing the MM2 force field option as described before. The aim of this is mainly to clean up geometry prior to applying an electronic method (Total energy = 17.897 kcalmol-1 ). Then, MOPAC/RM1 MO method was employed to generate an approximate representation of the valence-electron molecular wavefunction. To understand the reactivity towards electrophile of this molecule, we first look at the HOMO, for which is the most electron rich. The reaction that we are to consider is the reaction of 12 with dichlorocarbene. Reported by Halton et al, there is a high regioselectivity in the addition of dichlorocarbene, giving only the syn-monoadduct. i.e. Addition occurs across the C=C double bond which is on the same side as the C-Cl bond[6].

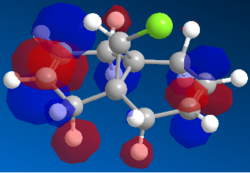

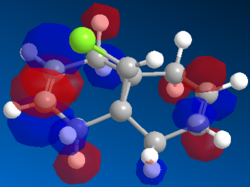

As shown in the above reaction scheme, dichlorocarbene reacts with 12 to give a di-adduct or a mono-adduct in the ratio 23:72[6]. And to investigate the regioselectivity observed, molecular orbitals (MOs) of 12 are computed, representing the electronic structure of the molecule. Below shows simulated MOs including HOMO-1, HOMO, LUMO and LUMO+1.

| HOMO-1 | HOMO | LUMO | LUMO+1 |

The HOMO shows that electron density only appears on syn double bond. This help rationalising the regioselectivity observed: the syn (to C-Cl bond) double bond will be attacked by a electrophile more readily compared to the anti double bond, which shows barely any electron density in the HOMO. The syn double bond is made more nucleophilic as a result of stabilising antiperiplanar interactions between the Cl-C σ* orbital and the occupied exo π orbital. Hence it is more susceptible to electrophilic addition.

In addition to MOPAC/RM1, we attempted to generate representation of the valence-electron molecular wavefunction using MOPAC/PM6 method. However, resultant molecular orbitals do not show the expected symmetry; molecule 12 has a Cs symmetry.

Vibrational Frequencies

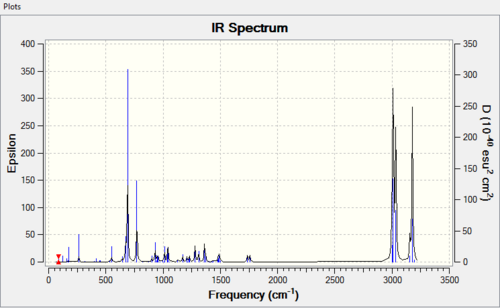

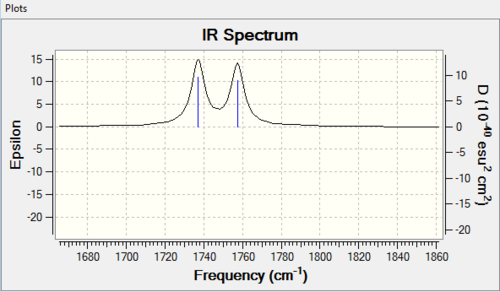

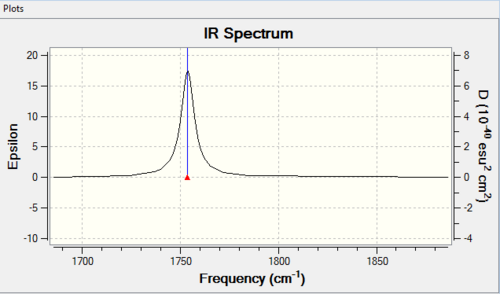

The aim of this section was to calculate and determine the influence of the C-Cl bond on vibrational frequencies of the molecule. Similar to above calculation is the use of MM2 force field option to first clean up geometries of molecules. Following this is a second optimisation using B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) Gaussian method. Here we are to computationally generate IR spectrum of 12 and its mono-hydrogenated derivative 13.

Optimisation by MM2 force field give energy of 17.897kcalmol-1 and 15.137kcalmol-1 respectively. Second optimisation using the Gaussian method and give predicted IR spectra shown below:

| Molecule | C-Cl stretch /cm-1 | syn C=C stretch /cm-1 | anti C=C stretch /cm-1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 770.9 | 1757.4 | 1737.0 |

| 13 | 780.0 | 1753.7 | - |

The data obtained gives both C-Cl stretching frequencies and C=C stretching frequencies consistent to literature values. (Lit[7],[8]: 780 (C-Cl stretch); 1620-1680 (C=C)). Comparing IR of the syn- and anti- C=C double bond IR frequencies in 12, a higher frequency in the syn double bond denotes a higher bond energy and thus a stronger bond. This seems to contradict what have been described so far that the syn- double bond is more reactive. Yet, another point to consider here is that what contributes to a C=C stretching frequency are both the σ and π bond while in electrophilic addition, we speak of only the π bond.

There is only a slight difference between the syn C=C bond in 12 and 13. This indicates that the anti-alkene does not affect the strength of of the syn-alkene in 12. In terms of C-Cl bond, it is found that C-Cl bond is stronger in 13 than 12 with a difference of 10cm-1 in stretching frequency. This is probably due to a loss of orbital interactions upon hydrogenation, i.e. less electron density is donated into the σ* orbital.

|

|

|

|

(A more technical aspect: when carrying out the calculation, the hydrogenated derivative will take longer time due to the asymmetric nature. On the other hand, having a Cs symmetry, the di-alkene 12 will improve the speed of calculation since only half of the molecule needs to be accounted for.)

Structure based Mini project using DFT-based Molecular orbital methods

This mini project involves an own choice of reaction from which two isomers are formed. It is common in organic reactions that a mixture of isomers are formed but the interest in here is to be able to identify one of the isomer from another. The reaction introduced below originates from the synthesis of yingzhaosu C[9]. Yingzhaosu C is an antimalarial peroxide with the structure shown below:

A very short total synthesis of yingzhaosu C was proposed:

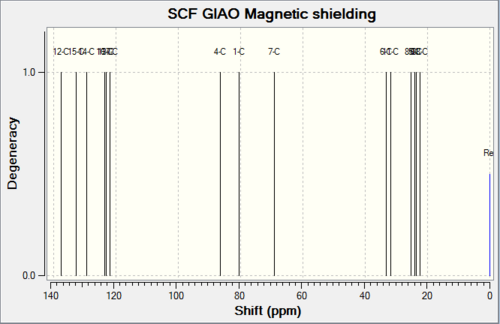

Here, 14 is converted to 15 prior to next step while 16 and 17 are separated by HPLC prior to conversion to 18 and 19 respectively. Stereochemical assignments of 16 and 17 (hence 18 and 19) could be achieved from their respective NMR properties. As assigned by J. Boukouvalas et al, especially revealing was a comparison between the 13C chemical shift of the 1,2-dioxane methyl substituent of 16 and 17(at 23.7 and 30.0 ppm respectively); suggesting that the methyl group was axial in the former but equatorial in the latter, for the six-membered cyclic peroxides are adopting a more stable chair conformation (see Carbon no. 9 in figure below). 13C NMR of product 18 and 19 also give the same observation. Similar results were also obtained by Xing-Xiang Xu and Han-Qing Dong[10]:23.9ppm and 30.1ppm for that methyl carbon in 18 and 19 respectively.

To reconfirm this spectral observation, the two molecules, 18 and 19 were constructed and optimised (by MM2 force field) in ChemBio3D. Then, corresponding 13C NMR spectra are predicted using the GIAO method:

1.Optimisation (minimising energy)

Further optimisation is performed by DFT method; DFT=mpw1pw91 was used together with 6-31G(d,p)as the basis set(See Jmol files below).

| 18 (optimised by DFT=mpw1pw91) | 19 (optimised by DFT=mpw1pw91) | ||||||

|

|

Optimisation with the described method gives an energy of 19.405kcal/mol and 17.845kcal/mol for 18 and 19 respectively. This shows that 19 is slightly more stable in energy than 18. However, the energy different is a bit small so we expect them to be formed to a similar extent. From literature, it is suggested the two products are formed in mixture in a 1.7:1 ratio. This shows consistency with our energy predictions. Although our focus here is to distinguish between the two stereoisomers using carbon 13 NMR, it is important to understand that enantiomers of 18 and 19 could also be formed. It is found in their stable conformers, the C-8 configuration is S for 18 and R for 19.

2. 13C NMR spectra simulation

Below shows spectra obtained as well as predicted chemical shifts, tabulated together with experimental chemical shift values[10].

Table 8. Comparison between the simulated and experimental C13 NMR

|

|

|

Simulated chemical shifts are very close to what have been suggested in literature with only small deviations (taking into account that error from simulation could lead to 2-4ppm difference for some peaks). Similar to what have been observed in literature, the key difference in chemical shifts of the 1,2-dioxane methyl substituent in the two isomers were successfully produced in simulation (ppm for 18 and ppm for 19). Anomalous results arise in chemical shifts of carbon 2,6 and 3,5: literature give single values for each pair of carbon, while simulations give distinct chemical shifts, suggesting absence of symmetry. This is perhaps due to overlap of peaks in literature results. Otherwise, difference between experimental and simulated chemical shifts is less than 5ppm.

Graphical representation of the 13C chemical shifts; Comparison between experimental results and simulated values:

Optical Rotation

As suggested, enantiomers of 18 and 19 would also be formed. Therefore, it is also sensible to investigate relative energies of each enantiomer and to predict corresponding optical rotation. However, it is found extremely difficult to have these structures correctly optimised. And due to time constraints, optical rotation calculation is not carried out.

Detailed enantioselective synthesis of these compounds could be found in literature quoted above.

Infrared Spectrum simulation

Infrared spectroscopy simulation was not considered here for 18 and 19 are stereoisomers.

Overall, the computationally simulated results shows a high consistency with experimental results. Yet, there is a lack of information regarding the mechanism of formation of product. Otherwise, more comments could have been made in the light of how the products are formed.

Refercences and Citations

- ↑ Pierluigi Caramella*, Paolo Quadrelli, and Lucio Toma, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2002, 124, 1130-1131: DOI:10.1021/ja016622h

- ↑ J.J. Zou, X. Zhang, J. Kong, L. Wang, Fuel, 2008, 87, 3655: DOI:10.1016/j.fuel.2008.07.006

- ↑ D. Skála, J. Hanika, Pet. Coal, 2003, 45, 105: PDF

- ↑ A.G. Shultz, L. Flood, J.P. Springer, J. Org. Chem., 1986, 51, 838: DOI:10.1021/jo00356a016

- ↑ W.F. Maier, P.v.R. Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103, 1891: DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 B. Halton, S.G.G. Russell, J. Org. Chem., 1991, 56, 5553: DOI:10.1021/jo00019a015

- ↑ G. Socrates, Infrared and Raman Characteristic Group Frequencies, 3rd Edition, 2001, p. 65.

- ↑ J. Coates, “Interpretation of Infrared Spectra, A Practical Approach", Encyclopedia of Analytical Chemistry, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Chichester, 2000

- ↑ J. Boukouvalas, R. Pouliot and Yvon Fréchette Tet. Lett., 1995, 36 (24), pp 4167-4170: DOI:10.1016/0040-4039(95)00714-N

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Xing-Xiang Xu, Han-Qing Dong, J. Org. Chem., 1995, 60 (10), pp 3039-3044: DOI:10.1021/jo00115a019