Rep:Mod:vrt

Victoria Thompson: Yr 3 Computational Labs Transition States Exercise

Introduction

A potential energy surface (PES) allows for the potential energy of a reaction to be plotted alongside a number of reaction coordinates. For a 1D PES; 1 reaction coordinate is incorporated, for 2D; 2 reaction coordinates are incorporated, etc. For a specific reaction, various maxima and minima energy states that lie on the PES, can be calculated. A minimum corresponds to an arrangement of the atoms involved in the reaction that is of low energy. There can be local and global minima where the global minima is the lowest point on the surface and the local minima is the minimum value within a given area. In both cases the curvature in all directions from these points is up. A maximum corresponds to a high energy state on the reaction pathway. At these points, the curvature points down in all directions.

Another point of interest on a PES is a saddle point. Here, like for maxima and minima, the gradient is equal to 0. On a 2D surface, this point is characterised as the maxima in energy on a reaction pathway between two minima. The curvature is down in the direction of the reaction coordinate but up in all other directions. A saddle point has one imaginery frequency associated with it.[1]

A transition state (TS) is the geometry of the molecule at the saddle point. Molecules must pass through this TS state to form products from the starting reactants. The energy barrier to reach the TS structure is the activation energy (Ea) for the particular reaction.

TS structures on a PES can be found using complex mathematics. A basic understanding of the transition state, for example: which bonds are made/broken and the orientation of the approaching molecules, is needed to obtain the final optimised structure. Throughout the following exercises, gaussview was used to employ various methods to find and optimise the TS structure and its energy. Three methods were presented that could be utilised to tackle the given exercises. Method one involved straight optimisation of a 'guessed' transition structure. Method two built on this by optimising the 'guess' structure by 'freezing' certain co-ordinates involved, then applying method one. In method three, the product was built and optimised, the bonds known to be formed in the reaction were broken and the species separated. This formed a structure resembling the approach orientation to the TS. Method two was then employed to optimise this. While method one and two were faster than method three, this method gave the most accurate TS structure. Working backwards from the product to the starting materials meant the correct orientation of the reacting species was always obtained. This method also does not require the user to have a detailed understanding of the TS chemistry. Upon finding the correct TS, (evidence for a TS can be found from running a frequency calculation where one imaginary vibration will be present, animation of this shows how the molecules move to create the TS) an Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) calculation was used to analyse the reaction pathway from one local minima to another.

Nf710 (talk) 15:23, 30 December 2016 (UTC) Good intro, you should have stated that the curvature is the second derivative of the PES in that dimension.

Diels Alder Background

The following exercises focus on locating and characterising transition states of three Diels-Alder (DA) reactions:

1. Butadiene + Ethylene

2. Cyclohexadiene + 1,3-Dioxole

3. o-Xylylene + SO2 (along with a comparison to a potential chelatropic reaction that can also occur between these two compounds)

The Diels-Alder reactions investigated are [4+2] cycloadditions, they involve the addition of a diene and a dienophile in a concerted manner through a cyclic transition state. In these reactions 2 π bonds are broken at the expense of forming 2 sigma bonds and a π bond, in a new position. The formation of sigma bonds is thermodynamically favourable (overall net energy is released by breaking the pi bonds) and this acts as the driving force for the reaction.

The reaction is described as either normal or inverse electron demand. The difference lies in the relative energies of the HOMO and LUMO of the reactants. For normal electron demand the dienes HOMO interacts with the dienophiles LUMO. Usually to facilitate this, the diene contains an electron donating group (EDG), increasing the energy of its HOMO, whilst the dienophile contains an electron withdrawing group (EWG), lowering the energy of its LUMO. This reduces the difference in energy between the dienes HOMO and dienophiles LUMO, so the relevant orbitals are closer in energy and greater stabilisation is gained from their combination to form molecular orbitals (MOs). In an inverse electron demand reaction, the HOMO of the dienophile and the LUMO of the diene interact. The EDG and EWG are placed on the other reactant with the same end result of reducing the HOMO to LUMO energy gap.

If the HOMO and LUMO have the same orbital symmetries as well as having a non zero overlap integral, the reaction is said to be allowed.[2] Forbidden DA reactions do not fulfill these conditions. The Woodward Hoffman rules can also be used to determine whether the reaction is thermally allowed or forbidden.[3] These rules state that thermal pericylic reactions are allowed if there are an odd number of total (4q+2)s + (4r)a components within the system under analysis. Subscript s and a highlight the suprafacial or antifacial nature of the involved orbitals.

Secondary orbital effects play an important role in these reactions. If the dienophile is subtituted with appropriate groups, extra orbital interactions occur that can stabilise the TS and lead to regiochemistry. A mixture of products, labelled endo and exo, can be formed due to this.

In the third reaction analysed there is possibility of a chelatropic reaction. A chelatropic reaction is a form of cycloaddition where the terminal atoms of a fully conjugated system form two new σ-bonds to a single atom of a monocentric reagent. There is formal loss of one π-bond in the substrate and an increase in coordination number of the relevant atom of the reagent. [4]

Optimisation methods used

Various optimisation methods were introduced in order to complete the following exercises. The principle aim of these methods is to solve the integrals present in the Hamiltonian matrix corresponding to the system in question. The most basic method was the semi-empirical PM6 method, this utilises pre-set values for some of the integrals, shortening the calculation time but compromising the accuracy of the result. The next optimisation method was DFT at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level. The Hamiltonian for this optimisation is a function of charge density, unlike for the PM6 method, all integrals must be evaluated. The exchange correlation term in the DFT calculation is given by the Hartree-Fock method and as a result, this level of optimisation produces results that are closer to experimental values but it more time consuming. The last method introduced was that of pure Hartree-Fock (HF). DFT can be considered a faster hybrid method involving this calculation. In HF, the Hamiltonian matrix is a function of the individual atomic positions comprising the system. As each atom has 3 position vectors, (x,y,z) this calculation can be extremely time expensive. Even though this method would give the best quantitative results. For all exercises the semi-empirical PM6 method was used. For exercise 2, this was combined with DFT at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level to obtain results. The Hartree-Fock method wasn't employed due to its time-consuming nature and the fact that this high level of optimisation was not necessary for the exercises.

It should be noted that due to the varying way in which the method calculations are completed, discrepancies between abstracted thermal data such as the activation and reaction energies is expected. On top of this, results from calculations completed by different methods cannot be compared, only results from calculations done using the same method can lead to meaningful comparisons.

Nf710 (talk) 15:26, 30 December 2016 (UTC) DFT is not a hybrid method. B3LYP is. Very good intro. good understanding of the theory.

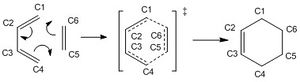

Exercise 1: Reaction of Butadiene with Ethylene

The semi-empirical PM6 method was employed in this exercise. Relevant bonds were frozen to optimise the reactants approach to the TS before calculations were completed.

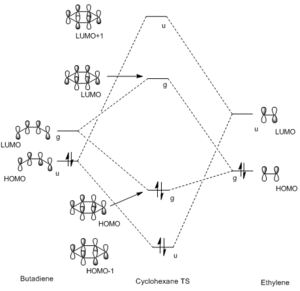

MO analysis

NOTE: g indicates the orbital is of gerade symmetry - so has a centre of inversion. u indicates ungerade symmetry - no centre of inversion

This is an example of a normal electron demand Diels Alder as the HOMO of the diene interacts with the LUMO of the dienophile to give the lowest energy MO. The HOMO and LUMO have the same orbital symmetries, g, meaning the reaction is allowed.[5] This relies on the fact that when an orbital interaction between orbitals of the same symmetry (gerade with gerade/ungerade with ungerade) occurs then the overlap integral is non-zero. When orbitals of different symmetries overlap (gerade with ungerade) the overlap integral is zero and there's no interaction between them and an MO cannot be formed.

Below are the Jmol files for ethylene, butadiene and cyclcohexene. This allows visualisation of the HOMO and LUMOs of the reactants and the MOs formed in the product that relate to those in the above MO diagram.

| Ethylene | Butadiene | Transition state | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Bond length analysis

| Bonded carbon atoms | Bond Length (Å) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reactants | Transition State | Product | Literature Values [6] | |

| C1-C2 | 1.33532 | 1.33747 | 1.50032 | 1.46 |

| C2-C3 | 1.4683 | 1.46983 | 1.33761 | 1.54 |

| C3-C4 | 1.3354 | 1.33384 | 1.50029 | 1.46 |

| C4-C5 | N/A | 2.21083 | 1.54003 | N/A |

| C5-C6 | 1.32741 | 1.32495 | 1.54070 | 1.32 |

| C6-C1 | N/A | 1.59419 | 1.53990 | N/A |

On going from reactants to products the double bonds at C1-C2, C3-C4 and C5-C6 become single bonds. The single bond between C2-C3 becomes a double bond. Thus, carbons at C1, C4, C5 and C6 change hybridisation from sp2 to sp3. This is demonstrated by the gradual lengthening the bonds at C1-C2, C3-C4 and C5-C6 and the decrease in length of the C2-C3 bond. The calculated bond lengths roughly match those of literature for the bonds of butadiene while the ethylene bond is extremely accurate with literature. The partially formed bond lengths between C4-C5 (2.21Å) and C6-C1 (1.60Å) are lower than double the Van der Waals radius of a carbon atom (1.7Å[7]) meaning there is significant interaction between the atoms at the TS.

Transition State Vibration

The animation above shows the imaginary vibration frequency of the TS at i948.98cm-1. It highlights that the terminal carbons of both butadiene and ethylene move towards each in a motion consistent with bond formation. The synchronous motion shows the bonds form at each terminal at the same time, implying a concerted reaction. This is consistent with a Diels Alder system where there are no substituents attached to either the 4π or 2π component. This means there is no favouring interaction for one bond forming first, such as when there is an EDG on the dienophile that can donate into a compatible acceptor orbital on the diene (for example, the π* of a C-EWG on the diene). There is also no unfavourable interactions from steric hindrance which would cause asynchronous overlap. The animation also highlights compression of the C2-C3 bond in butadiene showing its transition from a single to double bond.

Below shows the vibration relating to the lowest positive frequency 145.26cm-1 this shows the molecules vibrating in a different degree of freedom and does not relate to the reaction path.

Nf710 (talk) 15:35, 30 December 2016 (UTC) Excellent first section.

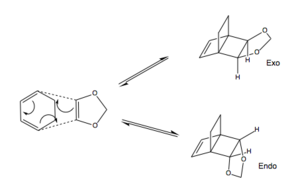

Exercise 2: Reaction of Cyclohexadiene and 1,3-Dioxole

For this exercise the PM6 level of optimisation was first used before reoptimisation with B3LYP method. This reduced the time taken for the B3LYP method to run. Freezing of bond coordinates was once again used to minimise the energy of the reactants approach to the TS. The imaginery frequencies for the endo TS using the PM6 and B3LYP levels was -471.95cm-1 for both. For the exo TS these values were: -471.95cm-1 and -528.82cm-1 respectively.

| Endo TS Jmol- HOMO (MO30) and LUMO (MO31) | Exo TS Jmol - HOMO (MO30) and LUMO (MO31) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(Four MOs are produced for each TS. Inclusion of an MO diagram would make this more clear. Otherwise, nice use of code Tam10 (talk) 16:27, 13 December 2016 (UTC))

In this reaction the dienophile is electron rich due to the presence of the adjacently bound oxygen atoms therefore, the Diels-Alder proceeds under inverse electron demand. The HOMO of the dienophile (1,3-dioxole) interacts with the LUMO of the diene (cyclohexadiene). These AOs are shown below.

| 1,3 - Dioxole - HOMO (MO14) and LUMO (MO15) | Cyclohexadiene - HOMO (MO16) and LUMO (MO17) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

These Jmols highlight that the HOMO of 1,3-dioxole is of the same symmetry as the LUMO of the cyclohexadiene. Therefore, the reaction is 'allowed'.

| Optimisation Method | TS Type | Reactants (KJ/mol) | TS (KJ/mol) | Product (KJ/mol) | |Ea| (KJ/mol) | |ΔGr| (KJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM6 | Endo | 0 | 192.57 | -70.32 | 192.57 | 70.32 |

| Exo | 0 | 195.10 | -70.41 | 195.10 | 70.41 | |

| B3LYP | Endo | 0 | 158.46 | -68.75 | 158.46 | 68.75 |

| Exo | 0 | 166.31 | -65.14 | 166.31 | 65.14 |

NOTE: The reactant energies were obtained from the sum of the individual reactant energies while at infinite separation from one another. This was justified as the reaction is completed in the gas phases where, by the ideal gas law, at infinite separation the molecules have no interaction energy[8] so the most accurate minimum energy for the reactants can be obtaibed. This is in agreeance with the Lennard-Jones potential where at infinite separation two non-bonding molecules have zero potential energy[9]. The values for the reactant energies were set to zero and the TS and product energies measured relative to this.

(Use a scale for the free energy and a reference point (reactants). Not a big deal as the values are shown clearly above Tam10 (talk) 16:27, 13 December 2016 (UTC))

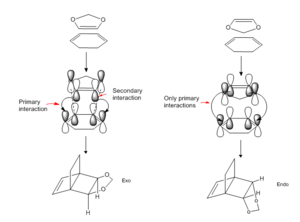

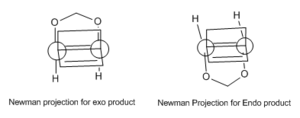

The above energy profile and table of energies allows determination of the kinetic and thermodynamic product. The kinetic product is the product with the lowest energy TS, it is the major conformer formed in an irreversible DA which proceeds under kinetic control. Here, there is only enough energy for the lower Ea barrier to be overcome. For the above reaction this is the TS on the pathway to the endo product. This TS is lower in energy than for the exo product due to a stabilising secondary orbital interaction between the dienophile and the developing π bond at the back of the diene. Specifically, an interaction between the p orbitals on the oxygen atoms and the corresponding p-orbitals on the terminal carbon atoms of the bond that will be the double bond of the product. This type of interaction is not possible in the conformation of the exo TS. The secondary orbital interactions are shown in the underneath, left hand side figure. These interactions can also be seen in the Jmol of the endo TS. Here the HOMO shows that the orbitals on oxygen and those on the carbons where the double bond will be are of the same symmetry and orientation to interact.

Although the endo TS is of lower energy the actual product is of higher energy compared to the exo one. This is due to steric hindrance. In the endo product the double bonded atom bridge eclipses the dioxole ring. In the exo product the single bond atom bridge eclipses the dioxole ring. The double bonded bridge has more electron density so it's repulsion for the dioxole ring is greater than that of the single bond bridge. This causes the endo product to be higher in energy.[10] This can be seen in the underneath, right hand side figure.

The thermodynamic product is the product that is of lowest energy. It's formed as the major conformer in reversible DA reactions where the reaction has enough energy so the higher Ea can be obtained. The reaction is said to proceed under thermodynamic control. For the reaction being analysed the thermodynamic product corresponds to the exo product.

LOG files for reaction energies data (Hartrees)

| Optimisation Method | TS Type | Reactants (Hartrees) | TS (Hartrees) | Product (Hartrees) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM6 | Endo | Dioxole Data file

and Cyclohexadiene Data file

|

Data file | Data file |

| Exo | as for Endo | Data file | Data file | |

| B3LYP | Endo | Dioxole Data file

and Cyclohexadiene Data file

|

Data file | Data file |

| Exo | as for endo | Data file | Data file |

NOTE: the conversion factor used to convert between Hartrees and KJmol-1 was 1 KJmol-1 = 3.8088x10-4 Hartrees

Nf710 (talk) 15:53, 30 December 2016 (UTC) This section was done very well. very clear and consise. well done. good understanding of the significance of the gas phase reaction.

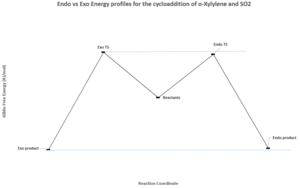

Exercise 3: o-Xylylene-SO2 Cycloaddition: Diels-Alder vs Cheletropic reactions

In this reaction, the optimisation method used was at the PM6 level. The products were formed first and the TS was worked out from this, as described by method 3 in the introduction. The imaginery frequencies were: -486.51cm-1, -334.12cm-1 and -351.23cm-1 respectively for the chelatropic, endo and exo TS.

| Chelatropic | D.A Endo | D.A Exo | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Animated IRC |  |

|

|

| IRC |  |

|

|

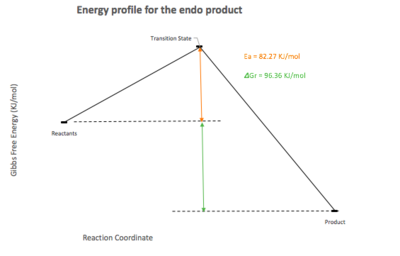

| Energy profile |  |

|

|

From the IRC movies it can be seen that the chelatropic TS proceeds in a symmetric, synchronous way where the bonds to SO2 form at the same time. For the endo TS, the bond to the oxygen of SO2 forms one frame before the bond to sulfur. However, this is only a minor delay so the mechanism is still considered as synchronous and proceeding in a concerted manner. This is the same for the exo TS.

| Ea (KJ/mol) | ΔGr (KJ/mol) | |

|---|---|---|

| Endo | 82.27 | 96.36 |

| Exo | 86.26 | 99.16 |

This data highlights that the endo product is the kinetic one due to the lower activation energy needed for the reaction and the higher product energy. The exo product is the thermodynamic one as the activation energy to reach the TS on this pathway is higher. This can be explained using similar arguments to experiment two. The endo TS is more stable than the exo one as there are secondary orbital interactions between the p orbital on the oxygen of SO2 that does not end up bonded to carbon, and one of the terminal carbons at the position where the double bond will be in the product. The endo product is of higher energy due to steric interactions between the oxygen and the bulk hydrocarbon part of the product. The exo TS has no stabilising secondary orbital interactions and the product is of lower energy due to less steric hindrance.

(Good section. For the endo IRC animation it's a little difficult to see from the angle chosen Tam10 (talk) 16:27, 13 December 2016 (UTC))

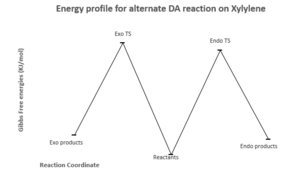

Alternate D.A reaction

A Diels Alder reaction can also occur between SO2 and the diene fragment contained within the ring of o-Xylylene. However, this variation of the reaction is thermodynamically and kinetically less favourable than when D.A proceeds using the exocyclic diene system. This is highlighted by: the higher Ea for this process and the higher energies of both the product molecules to the corresponding reactants. This means the reactants reside at a lower minima in the PES so it's more energetically favourable for the system to be at this position.

Again, the endo product would be the kinetic product and exo product the thermodynamic product due to reasons already outlined in the previous examples.

| Ea (KJ/mol) | |ΔGr| (KJ/mol) | |

|---|---|---|

| Endo | 112.494749 | 16.76906111 |

| Exo | 120.3292375 | 21.21665615 |

Instability of o-Xylylene

The above diagram shows the decomposition pathways available for o-Xylylene. o-Xylylene can be isolated at -78°C. Upon heating this to 0°C, dimerisation to compound 1 occurs. When o-Xylylene is prepared by heating a sulfone in diethylphthalate, dimerisation to compound 2 occurs. Finally, in the vapour phase, o-Xylylene ring closes via an electrocyclic mechanism (shown below) to give compound 3.[11]

Evidence for this electrocyclic reaction is in the IRCs of the previous reaction analysis. Here, the bonding within o-Xylylene become delocalised due to the presence of a conjugated π-system. The ring is seen to go through an aromatic stage which can be isolated by ring closing of the exocyclic double bonds.

| TS Imaginary vibration | TS IRC animation |

|---|---|

|

|

The presence of a TS state is proven by an imaginary frequency at -858.10cm-1. This is shown in the above animation. The animated IRC is also shown.

Regarding the previously mentioned Woodward Hoffman rules; in the above example, the reaction system can be thought of as either an antifacial 8π or 4π system where r = 2 or 1 respectively. Therefore, there are an odd number of total (4q+2)s + (4r)a components and the reaction is thermally allowed. This reaction proceeds in a conrotatory fashion where the orbitals at the end of the conjugated π system rotate in the same direction (this is opposed to a disrotatory fashion where the terminal orbitals rotate in different directions). Evidence for conrotation is shown in the table below. In the HOMO of the TS there is a blue orbital extending from one carbon to the next where the new sigma bond forms across the end of the old π system. This orbital extends from the top of one carbon to the bottom of the adjacent one showing the opposite lobes of the orbitals end up bonded together and for this to happen the orbital both have to rotate in the same direction.

Overall the reaction is thermodynamically favourable as the formation of 3 C-C sigma bonds and one C=C π bond outweighs the energy loss from breaking two C=C π bonds. The energies of these bonds[12] and overall net energy of the reaction are shown below.

C-C bond energy = 346 KJmol-1

C=C bond energy = 615 KJmol-1

Calculation: 2(615)-[3(346)+(615)] = -423 KJmol-1

ΔH is negative so the reaction is exothermic and energy is released. As there is only one reactant and one product molecule, there is no entropy change, therefore, ΔG solely depends on ΔH. As ΔH is negative the is spontaneous.

| o-Xylylene - HOMO (MO20) and LUMO (MO21) | Transition state - HOMO (MO20) and LUMO (MO21) | Benzocyclobutane - HOMO (MO20) and LUMO (MO21) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The above table shows the HOMO and LUMO orbitals of the reactant, TS and product.

(Good analysis. Could be useful to calculate reaction barrier to see if it is a competing pathway Tam10 (talk) 16:27, 13 December 2016 (UTC))

Conclusion

Overall, computational methods have been used to show how the orbitals of molecules interact in example Diels Alder reactions. The HOMOs/LUMOs generated gave an insight into the reactions categorisation as normal or inverse electron demand and whether the reaction proceeded in an synchronous or asynchronous manner.

From knowledge of the Ea and ΔGr the pathways could be determined as being under kinetic or thermodynamic control - where the reaction with a higher Ea and lower product energy showed thermodynamic control and a lower Ea but higher product energy showed kinetic control.

This analysis has enabled collection of data about different TS. This is difficult to collect experimentally as TS structures cannot be isolated due to them corresponding to a maximum on a PES, so the molecule prefers to be in a lower energy arrangement, and having a short lifetime.

References

- ↑ E.G. Lewars, Computational Chemistry, Springer, 2011, pp 17

- ↑ C.H. Longuet-Higgins, E. W. Abrahamson, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1965, 87 (9), pp 2045

- ↑ J. Clayton, N. Greeves, S. Warren, Organic Chemistry, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2001, pp 892

- ↑ PAC, Glossary of terms used in physical organic chemistry (IUPAC Recommendations 1994), 1994, pp 1094

- ↑ C.H. Longuet-Higgins, E. W. Abrahamson,J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1965, 87 (9), pp 2045

- ↑ F. H. Allen, O. Kennard, D. G. Watson, L. Brammer, G. Orpen, R. Taylor, J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2, 1987, S1-S19

- ↑ A. Bondi. J. Phys. Chem., 1964, 68 (3) pp 441–51

- ↑ P. W. Atkins, J. De. Paulo, Atkins' Physical Chemistry, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2014, pp 193

- ↑ P. W. Atkins, J. De. Paulo, Atkins' Physical Chemistry, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2014, pp 677

- ↑ J. Clayton, N. Greeves, S. Warren, Organic Chemistry, Oxford University Press, 2001 pp 884-885

- ↑ E. Murray, Thermal Electrocyclic Reactions, Academic Press, Inc., 1980, pp 147-148

- ↑ R.S. Boikess, Chemical Principles for Organic Chemistry, Rutgers, The State University of New Jerset, 2013, pp 30