Rep:Mod:tb407 Inorganic Module 2

Module 2:

The BH3 molecule

Optimisation of BH3

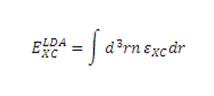

A molecule of BH3 was drawn using GaussView (fig. 1.) The initial drawing of the molecule was set such that the dihedral angles were set to 120o and the boron hydrogen separation was 1.5 Å. This was to assist the subsequent geometry optimisation in finding the lowest energy of the system.

The geometry of the system was optimised using the following parameters.

| Parameter | Method |

|---|---|

| Calculation method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 3-21G |

| Spin | Singlet |

| Energy / Atomic Units | -26.46 (2 dp) |

| RMS Gradient Norm / Atomic Units | 0.00021 |

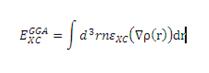

The calculation method RB3LYP determines what approximations are made in the quantum mechanical calculations. The method is a "generalised gradient approximation", which gives a better of molecular exchange-correlation energies and bonds than local spin density models. The exchange-correlation energy is a prediction of the molecular energy, which takes into account the correlation of electrons within a molecule, i.e. how they interact, and the echange interaction, which is an effect by which the wavefunctions of two particels can overlap to give an apparent energy, which can be larger or smaller than that expected. A local density approximation (LDA), uses local electron density at different points in space to try and approximate the exchange-correlation energy (eqn. 1[1].)

Since the electron density in molecules is not constant however, but changes accross the molecule, the LDA is not a good enough approximation for the optimisation of BH3. In this case, this problem is solved by not using regions of localised electron density but by taking the gradient of the electron density (eqn. 2[2].) This gives rise to results, which can be at least as accurate as semi-empirical methods such as the MOPAC package used in Module 1. The energies calculated are reported to be particularyl accurate for small molecules[3], thus making them ideal for calculations involving BH3.

The basis set used was 3-21G. A basis set, is a series of simple functions, which are combined to approximate a more complex function. In the case of calculating molecular orbitals, the basis set can be atomic orbitals. In the case of calculation of frequencies, the basis set may simply be the cartesian axes, x,y and z. The 3 represents the "degree of contration"[4], which is the number of primitive Gaussian functions, which approximate each atomic orbital. Thus 3-21G is a relatively small basis set, compared to the larger 6-31G for example, and really is not accurate enough to model molecules. However, the calculations run very quickly compared to those which use higher level basis sets such as LANL2MB or LANL2DZ and thus it is convenient to use it here.

The gradient reported as 0.00021 suggests that convergence has been reached and thus the molecule has been properly optimised. This is confirmed by the .log file, which gives the following result.

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000413 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000271 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.001610 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.001054 0.001200 YES Predicted change in Energy=-1.071764D-06 Optimization completed. -- Stationary point found.

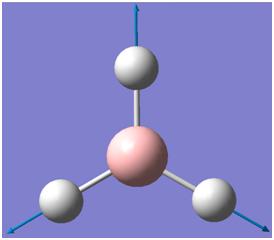

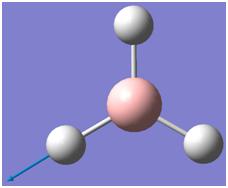

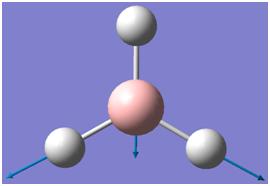

The optimised molecule can be seen below.

The variation of energy and gradient (force) with optimisation time is shown in fig. 2.

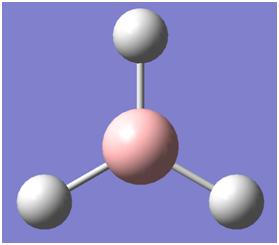

In the optimisation, the energy of the molecule must be minimised, and thus the final product (reached at the final step) has the most negative energy (-26.46 a.u (2dp.) This energy is in quite good agreement with that reported in the literature[5] of -26.38 a.u. As can clearly be seen, convergence is reached in just four steps. This means that at the fourth step, varying the geometry of the compound (bond lengths and angles) no longer has a significant effect on the energy (and thus gradient) of the molecule. This explains why there is much less of a difference between the final two optimisations compared to the first three. Each change in the bond length corresponds to a step towards the equilibrium position of the Lennard-Jones potential from the situation where the atoms repel each other. The reason that the gradient must be as small as possible in te optimised structure is because this is the stationary point of the curve, corresponding to the equilibrium positioning of the atoms. The intermediate geometries, through which the optimisation moved, are shown in figure 3.

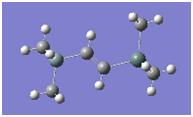

Fig. 3: Intermediates in the optimisation of BH3. Bond lengths are (left to right): 1.5Å, 1.41Å, 1.23Å and 1.19Å

It can be seen that for the first two compounds, there are no bonds drawn on the molecule. This is because, as far as Gaussian is concerned, bonds are simply lines connecting atoms and have a set length. This is obviously not the case in reality, where a bond is simply the sharing of electrons between atoms, which results in them forming a "molecule", since both atoms need the electrons and thus they begin to move around together, giving rise to a new entity.

The optimised bond angle remains 120o and the optimised bond length is found to be 1.19Å (2dp.) This compares well with those values predicted in the literature for this molecule using higher level theoretical studies (self consistent field [SCF] calculation method, double-ζ plus polarisation [DZP] basis set) of 1.19Å (2dp)[6]. This implies that a high level calculation is slightly overkill for BH3, which will be modelled quickly and easily using a basic B3LYP method and 3-21G basis set.

Molecular Orbitals of BH3

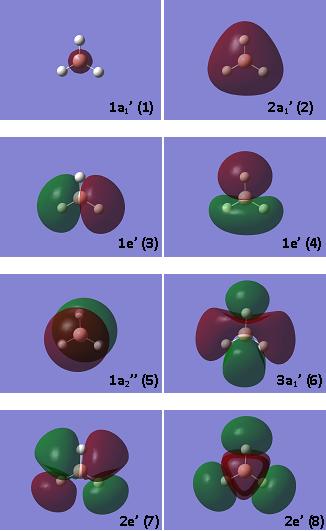

The molecular orbitals of the B3LYP/3-21G optimised BH3 structure were calculated using the same method and basis and the following molecular orbital diagram was generated. The MOs for the first eight energy levels are pictured.

The form and approximate relative energies of the molecular orbitals can be predicted using the linear combination of atomic orbitals (LCAO) method. Using this method, the following molecular orbital diagram is generated[7].

Although not pictured, there is a 1a' orbital, which corresponds to a non-bonding boron 1s orbital, which is too low in energy to interact with any orbitals of the H3 fragment.

It can be seen that, generally, there is good agreement between the actual MOs (calculated) and those predicted by the LCAO method. In fact, the physical shapes of the orbitals match almost perfectly between theoretical and calculated MOs. Furthermore, both diagrams show the non-bonding p-orbital (1a2ll) to be the LUMO. The only difference lies in the relative energies of the orbitals. The LCAO method predicts that the two degenerate 2e' orbitals will be the highest in energy and that, lying just below them in energy, the 3a1' orbital will follow. This is not backed up by the computer calculations, which suggest that the two degenerate 2e' orbitals will be lower in energy. This illustrates one of the shortcomings with the LCAO method, which is very hit-and-miss when it comes to predicting the exact ordering of the energy levels. This is due to the fact that there are no hard and fast rules for how large the splitting between bonding and anti-bonding orbitals is, simply guidelines such as the general rule that the closer the orbitals in energy, the greater the splitting.

However, in spite of the small difference in ordering of the energy levels, there is no denying that LCAO remains a useful, relatively quick, benchtop method for predicting MOs, but should not be relied upon as completely accurate.

NBO analysis of BH3

The natural bond orbital analysis was carried out on the .log file from the molecular orbital calculation job.

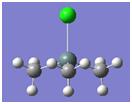

The atoms in the optimised molecule were coloured according to their charge (fig. 3.)

| Atom | Charge |

|---|---|

| B | 0.332 |

| H | -0.111 |

| H | -0.111 |

| H | -0.111 |

The bright green colour of the B atom, demonstrates that it has a much more positive atomic charge cf. the hydrogen atoms (+0.332 vs -0.111.) This reflects the highly Lewis acidic character of the compound and also ties in with the results from the MO calculation, which showed the LUMO to be the empty pz orbital, localised on the boron atom, which is available for donation and thus the region of higest positive charge.

This data is summarised in the fragment of the .log file below.

Summary of Natural Population Analysis:

Natural Population

Natural -----------------------------------------------

Atom No Charge Core Valence Rydberg Total

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

B 1 0.33161 1.99903 2.66935 0.00000 4.66839

H 2 -0.11054 0.00000 1.11021 0.00032 1.11054

H 3 -0.11054 0.00000 1.11021 0.00032 1.11054

H 4 -0.11054 0.00000 1.11021 0.00032 1.11054

=======================================================================

* Total * 0.00000 1.99903 6.00000 0.00097 8.00000

The NBO analysis file can also give important information about the s and p atomic orbital content of the various bonds, allowing the quantum mechanical calculations to be fitted to a more familiar idea of sp3/sp2 bonds. The part of the .log file relating to the four occupied orbitals (three bond orbitals and one core orbital) is given below.

(Occupancy) Bond orbital/ Coefficients/ Hybrids

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1. (1.99853) BD ( 1) B 1 - H 2

( 44.48%) 0.6669* B 1 s( 33.33%)p 2.00( 66.67%)

0.0000 0.5774 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

0.8165 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

( 55.52%) 0.7451* H 2 s(100.00%)

1.0000 0.0000

2. (1.99853) BD ( 1) B 1 - H 3

( 44.48%) 0.6669* B 1 s( 33.33%)p 2.00( 66.67%)

0.0000 0.5774 0.0000 0.7071 0.0000

-0.4082 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

( 55.52%) 0.7451* H 3 s(100.00%)

1.0000 0.0000

3. (1.99853) BD ( 1) B 1 - H 4

( 44.48%) 0.6669* B 1 s( 33.33%)p 2.00( 66.67%)

0.0000 0.5774 0.0000 -0.7071 0.0000

-0.4082 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

( 55.52%) 0.7451* H 4 s(100.00%)

1.0000 0.0000

4. (1.99903) CR ( 1) B 1 s(100.00%)

1.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

The first four listed orbitals are the occupied orbitals (two per orbital.) The fourth listed shows 100% s character localised on the boron atom. This suggests that it is the low lying 1s orbital (missed out in the LCAO picture above), which does not interact at all with the H3 fragment. Orbitals 1,2 and 3 show 33.33% s character and 66.67% p character, which corresponds to the well known hybridisation state, sp2. This is completely in line with what is expected, both from LCAO and from VSEPR theory. Looking further down the .log file, it can be seen that the eighth orbital listed has the lowest energy of all of the unoccupied orbitals.

Natural Bond Orbitals (Summary):

Principal Delocalizations

NBO Occupancy Energy (geminal,vicinal,remote)

====================================================================================

Molecular unit 1 (H3B)

1. BD ( 1) B 1 - H 2 1.99853 -0.43712

2. BD ( 1) B 1 - H 3 1.99853 -0.43712

3. BD ( 1) B 1 - H 4 1.99853 -0.43712

4. CR ( 1) B 1 1.99903 -6.64476 10(v),11(v),12(v)

5. LP*( 1) B 1 0.00000 0.67666

6. RY*( 1) B 1 0.00000 0.37177

7. RY*( 2) B 1 0.00000 0.37177

8. RY*( 3) B 1 0.00000 -0.04532

9. RY*( 4) B 1 0.00000 0.43446

10. RY*( 1) H 2 0.00032 0.90016

11. RY*( 1) H 3 0.00032 0.90016

12. RY*( 1) H 4 0.00032 0.90016

13. BD*( 1) B 1 - H 2 0.00147 0.41201

14. BD*( 1) B 1 - H 3 0.00147 0.41201

15. BD*( 1) B 1 - H 4 0.00147 0.41201

Checking back, it can be seen that this orbital possesses 100% p character.

8. (0.00000) RY*( 3) B 1 s( 0.00%)p 1.00(100.00%)

This verifies once again that the LUMO is in fact the unoccupied, Rydberg orbital, the empty pz orbital. The degree of mixing can be determined from the .log file too. Since there is no significant contribution (i.e. greater than 20 kcal mol-1) in the Second Order Perturbation Theory Analysis section, it can be assumed that there is no significant mixing. This is confirmed by the LCAO predicted molecular orbitals, which don't show any orbitals close enough in energy and of appropriate symmetry to allow mixing.

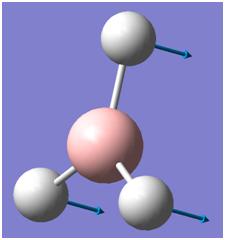

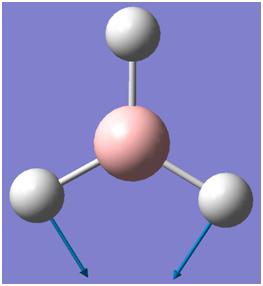

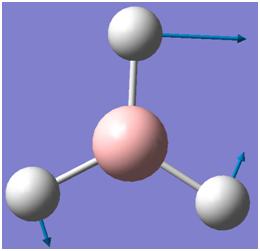

Vibrational Analysis of BH3

The vibrations of the molecule were calculated using the same basis set and method as the other calculations.

The energy of the molecule reported after the calculation was close enough to the original optimised energy, to allow us to make the assumption that the frequency calculation has run properly.

Non linear molecules possess 3N-6 vibrations. The six discounted vibrations are due to centre of mass motions. After the optimisation, these vibrations should be as close to zero as possible. The first vibration has frequency 1144.15 cm-1, the largest discounted vibration is 0.2123 cm-1. The low frequencies get closer to zero as the calculation gets better.

The calculated vibrations of the BH3 molecule are summarised in table 3.

These calculated frequencies are in relatively good agreement with those calculated and reported in the literature[8]: A1' = 2620 cm-1, A2`` = 1270 cm-1, E' = 2810 cm-1, E' = 1300 cm-1. Since all of the frequencies are positive, it can be rationalised that the minimum point has been reached by this optimisation rather than a transition state.

The computed IR spectrum can be seen in figure 3.

Although there are 6 calculated frequencies, only 3 signals are observed in the predicted spectrum. There are several reasons for this. First of all, the A1 vibration is not IR active, since it does not involve a change in the dipole moment of the molecule, and thus does not appear in the spectrum. There are also two sets of doubly degenerate vibrations (2 x E'), which only give rise to one peak per pair. Thus the peaks appearing on the IR spectrum correspond to two E' vibrations and one A2`` vibration.

The BCl3 molecule

Structural Analysis of BCl3

The BCl3 structure was optimised using B3LYP and the LANL2MB basis set.

| Parameter | Method |

|---|---|

| Calculation method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 3-LANL2MB |

| Spin | Singlet |

| Energy / Atomic Units | -69.44 (2 dp) |

| RMS Gradient Norm / Atomic Units | 0.000059 |

The optimised structure was verified by checking the .log file:

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000118 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000077 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000513 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000336 0.001200 YES Predicted change in Energy=-9.162732D-08 Optimization completed. -- Stationary point found.

Analysing the freqencies verifies that the structure found is a minimum, since all frequencies are positive. This is why the frequencies must be analysed, since it verifies that the optimised structure is a minimum energy structure cf. transition state. The same basis set must be used in order to ensure that the molecule is in the same electronic state for all calculations i.e. so that the optimisations are always ground state and not excited state.

The absorption frequencies are similar to those for the BH3 molecule. The symmetry of the vibrations are the same as those for BH3, but the frequencies themselves differ. Generally they can be seen to be lower than those computed for the BH3, this suggests weaker bonding than that present in BH3. This can be rationalised in terms of the overlap between the atomic orbitals. Chlorine is a much larger atom than hydrogen and thus the orbitals are much larger and diffuse. This means that there is less efficient overlap between these orbitals and the more contracted boron orbitals than there is between the boron and the core-like hydrogen atoms, resulting in a weaker bond and thus smaller frequency.

The optimised bond lengths (B-Cl) are reported to be 1.87Å and the optimised bong angles are reported as 120.0o. This is good agreement with the literature values of 1.78Å[9] and 120o.

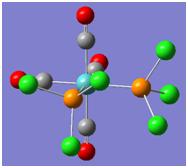

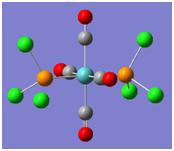

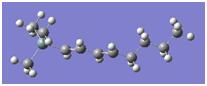

Cis and trans Isomers of Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2

The method used for these calcuilations was once more the B3LYP method. This time two optimisations were run, first using a LANL2MB basis set and then using a LANL2DZ basis set.[10][11][12][13]

In order to gain the correct minimum energy points, the initial optimised LANL2MB structures were modified. The cis isomer was set so that a Cl of one PCl3 group pointed up, parallel with the axial bonds, and the other group has a Cl pointing down. The trans isomer was set so that the two PCl3 groups are eclipsed and parallel with one of the Mo-C bonds.

The calculation can be seen to have converged using the .log file for the optimisation.

Cis Molybdenum Complex

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000100 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000029 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000907 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000344 0.001200 YES Predicted change in Energy=-1.018126D-07 Optimization completed. -- Stationary point found.

Trans Molybdenum Complex

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000062 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000017 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000908 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000233 0.001200 YES Predicted change in Energy=-4.170999D-08 Optimization completed. -- Stationary point found.

All frequencies calculated for both isomers are positive verifying that the optimisations correspond to energy minima in the potential energy curves.

The cis molecule has a Mo-C bond length of 2.06Å and an Mo-P bond length of 2.51Å. The trans molecule has Mo-C = 2.06Å and Mo-P distance of 2.44Å. These bond lengths are in line with literature results. The Mo-P bond length in trans-Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2, is 2.500Å[14] as determined by X-Ray crystallography. The Mo-C bond length is reported as 2.005Å. The computed P-Mo-P angle is 177.4o vs. 180.0o literature. Thus there is good agreement between the computer calculated angles and the experimentally determined angles. The analogous cis compound in the literature has Mo-P bond length 2.576Å. The agreement between literature and computed results is reasonably good but more importantly, the computer has accurately predicted that the bond length in the trans compound is shorter than that in the cis. The lengthening of the bonds in the cis occurs in order to to reduce the unfavourable steric clash between the bulky phosphine groups.

The energy of the two optimised molecules are very similar but slightly different. The difference between the energies of the isomers is found to be 2.73 kJ mol-1, with the cis geometry having the slightly lower energy. This is in contrast to what is expected, since the trans compound should be more stable, since the steric bulk of the phosphine ligands destabilises the cis compound. The energy difference between the two compounds may be increased (and inverted so that the trans product is favoured) by increasing the steric bulk of the phosphine ligand, so that the steric clash inherent in the cis compound is so large that it is too unstable to form. For example, if SiMe3 groups replaced Cl atoms, it is reasonable to assume that the cis compound would be less stable than the trans form.

There are no negative frequencies[15][16] in either the cis or trans vibrations calculated. There are, however, some very low frequency (and thus low energy) vibrations predicted for the trans isomer. At room temperature (T=298 K), kT = 2.476 kJ mol-1. There are 23 vibrations in the trans molecule, which can occur at room temperature i.e. that have energies less than kT, which corresponds to 207.1 cm-1. Similarly, there are 21 in the cis molecule.

The computed IR spectrum of the cis compound is given in figure 4.

The important peaks in this spectrum are the four vibrations at 2023, 1958, 1948 and 1945 cm-1 (lit. approx. 2023, 1927, 1908, 1897 cm-1[17]) corresponding to two A1 vibrations, one B1 and one B2 vibration. This is completely in line with the spectrum reported in the literature.

The computed IR spectrum of the trans compound is given in figure 5.

Here there are only two vibrations of an intensity significant enough to give rise to a peak in the IR spectrum, in this case the peak at 1950 cm-1 (lit. approx. 1900 cm-1[18].) This is in line with the spectrum observed in the literature.

The trans spectrum does not show all of the expected vibrations i.e. it only shows one band (2 vibrations) whereas there should be four 1950, 1951, 1977, 2031 cm-1. The reason for this is due to the fact that the 1977 and 2031 cm-1 vibrations do not involve a change in the overall dipole moment of the molecule and therefore have very low intensity and do not show up in the spectrum.

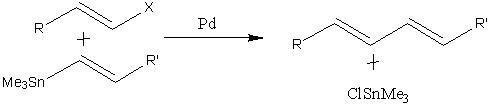

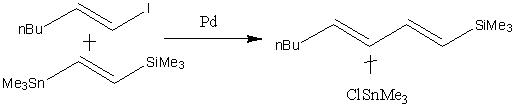

Mini Project: the Stille Reaction

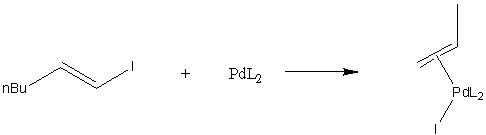

The Stille reaction is a highly specific reaction, which occurs between a vinyl halide and vinyl tin compound in the presence of a palladium catalyst to give a coupled product (fig. 6.)

The purpose of this mini-project is to optimise the reactants and products of the reaction, to determine their relative energies and to examine the nbo's, MOs and frequencies of the compounds and then to examine the effects of varying substituents on the tin compound and vinyl halide on the reactivity/MOs of the compounds.

First of all, the following example, taken from the Journal of the American Chemical Society, was optimised using the B3LYP method and the LANL2MB basis set. It was then optimised once more using a higher level basis set (LANL2DZ.)

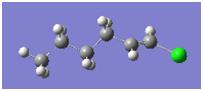

The optimised reactant and product structures are shown below.

The following details are provided in the .log file about each compound

| Compound | Calculation Type | Calculation Method | Basis Set | Energy/Atomic Units | Gradient/Atomic Units | Dipole Moment/Debye |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vinyl Chloride | FOPT | RB3LYP | LANL2DZ | -250.15 | 0.000020 | 2.86 |

| Tin Reagent | FOPT | RB3LYP | LANL2DZ | -324.15 | 0.0000028 | 0.02 |

| Coupled Product | FOPT | RB3LYP | LANL2DZ | -436.26 | 0.0000023 | 0.80 |

| Me3SnCl | FOPT | RB3LYP | LANL2DZ | -138.12 | 0.000021 | 4.33 |

If the energies of the products and the reactants are summed separately, they can be directly compared to establish, which side of the reaction is thermodynamically preferred.

The total energy of all the reactants is found to be -574.3 a.u. and the energy of the products is found to be -574.38 a.u. Let ER be the energy of the reactants and EP be the energy of the products.

The energy difference, ΔE, is defined by ΔE = EP - ER

ΔE = -574.38 - (-574.3)

ΔE = -0.08 a.u

ΔE = -210.04 kJ mol-1

This suggests that the products are more thermodynamically stable i.e. have a lower energy than the reactants. This is as expected, since it is known that this reaction readily goes to completion without heating[19].

A frequency analysis was carried out on each compound using the same method and basis set in order to verify that the minimum point in the energy has been reached. This was confirmed by the positive frequencies calculated.

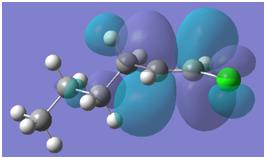

NBO and MO analysis was carried out on the vinyl halide, to try and rationalise the reactivity of the compounds.

Calculation of the HOMO and LUMO specifically can be used to rationalise reactivity and mechanisms.

As can be seen, the LUMO is dominated by the alkene antibonding orbital, and this is likely to be the orbital, which reacts with the palladium catalyst in the first step.

Thus, it is likely that the very first step involves coordination of the alkene bond to the palladium (see below.)

As well as coordinating the alkene, the alkene-halogen bond must be broken. This is easier for compounds in which the orbitals of the halogen and of the carbon do not overlap well. For chlorine, orbital overlap is reasonably good and the bonds are quite strong. Thus the energy of the vinyl halide is lower and it is more stable.

Now, the effect of varying the halogen on the vinyl halide can be investigated. The same optimisations as carried out previously (and frequency, MO and nbo calculations) were run using the same basis set and calculation method as before.

| Compound | Calculation Type | Calculation Method | Basis Set | Energy/Atomic Units | Gradient/Atomic Units | Dipole Moment/Debye |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vinyl Fluoride | FOPT | RB3LYP | LANL2DZ | -335.05 | 0.000018 | 2.72[21] |

| Vinyl Bromide | FOPT | RB3LYP | LANL2DZ | -248.37 | 0.000039 | 2.65[22] |

| Vinyl Iodide | FOPT | RB3LYP | LANL2DZ | -246.59 | 0.000033 | 2.32[23] |

If these energies are substituted for the energy of the vinyl chloride reagent in the first calculation, it can be established whether the halogen has any effect on the thermodynamics of the reaction.

| Vinyl halide | ΔE/a.u. |

|---|---|

| Vinyl Fluoride | -335.05 |

| Vinyl Chloride | -250.15 |

| Vinyl Bromide | -248.37 |

| Vinyl Iodide | -246.59 |

The difference between the vinyl halide, X, and vinyl fluoride, which is the most stable (has the most negative energy) compound can show the relative stabilities of these reactants very easily.

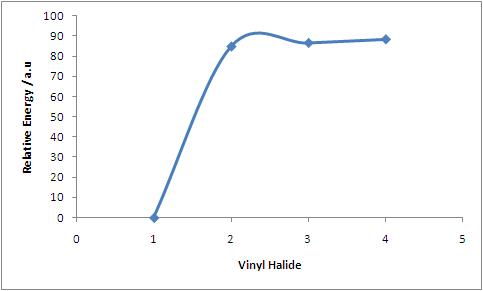

Graph of Relative Energy of vinyl halide (compared to vinyl fluoride) vs. halide

NB. x-axis: 1 = F, 2 = Cl, 3 = Br, 4 = I

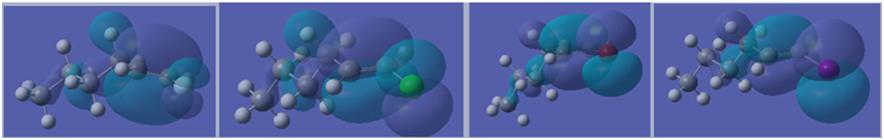

Thus it can clearly be seen that as the halogen group is descended, the relative stability of the vinyl halide drops. This suggests an increase in rectivity and thus it can be expected that iodides and bromides are the reagents of choice in the Stille Reaction. This increase in reactivity as the group is descended can be further observed in the molecular orbitals calculated. As the group is descended, the orbitals get more and more diffuse (see below: left to right - fluoride, chloride, bromide, iodide), thus reducing the bond strength and increasing reactivity. Furthmore, although the LUMO for vinyl fluoride and chloride are alkene pi antibonding based, the LUMO for the bromide and iodide are based on the sigma antibonding orbital of the C-X bond. This means that it is easier to break the C-X bond and enter the catalytic cycle.

The effect of varying the electronic nature of R on the vinyl halide was also investigated. The vinyl iodide was modelled using first an electron withdrawing group (EWG), CO2Me and then an electron donating group (EDG), NH2. The method used was B3LYP and the basis set was LANL2DZ. The frequencies calculated in the frequency analysis were all positive, suggesting that the optimised structure (minimum point) has been reached.

The energy of the n-butyl vinyl iodide was reported as -246.59 a.u. Optimisation on the same structure with a CO2Me group in place of the n-butyl group yielded a product with a much more stable energy (-317.20 a.u.) This suggests that electron withdrawing substituents slow down the rate of reaction of the vinyl halide in the Stille reaction.

If an EDG is placed on the alkene (NH2 here), the energy of the product rises to -144.71 a.u. This would result in an increase in the rate of reaction, since it reduces the stability of the reactant relative to the product. Donation of electron density from the nitrogen into the C-N sigma antibonding orbital weakens the C-N bond and causes electron density from the alkene pi bond to be donated into the C-X sigma antibonding bond. This weakens the C-X bond, which makes it easier for the C-X bond to break so that the oxidative addition to the palladium catalyst can occur.

Molecular Orbital Analysis of vinyl chloride

The IR spectrum of the vinyl chloride reagent was predicted using B3LYP/LANL2DZ.

The two weak peaks at 3256 and 3180 cm-1 correspond to stretches of the alkene CH bonds. The combination of peaks giving rise to the intense peak at about 3024 cm-1, are mainly CH stretching modes, as are the stretches giving rise to the intense peak at about 3032 cm-1. The peak at 1692 cm-1 corresponds to a C=C alkene stretching mode. The peaks at 1532 cm-1 are mainly due to CH bends. The small peak at 1436 cm-1 is due to CH3 bending modes. The small collection of peaks between 1250-1300 are due to CH2 bends.

References

- ↑ J.P. Perdew, K. Burke, M. Ernzehof, Phys. Rev. Lett., 1996, 77, pp. 3865

- ↑ J.P. Perdew, K. Burke, M. Ernzehof, Phys. Rev. Lett., 1996, 77, pp. 3865

- ↑ J.P. Perdew, K. Burke, M. Ernzehof, Phys. Rev. Lett., 1996, 77, pp. 3868

- ↑ V.A. Rassolov, J.A. Pople, M.A. Ratner, T.L. Windus, J. Chem. Phys., 1998, 109, pp. 1223

- ↑ M. Gelus, W. Kutzelnigg, Theoret chim Acta, 1973, 28, pp. 105

- ↑ J.M. Galbraith, G. Vacek, H.F. Schaefer III, J Mol Struct, 1993, 300, pp. 283

- ↑ Reproduced from 2nd Year "Molecular Orbitals in Inorganic Chemistry" lecture course (Imperial College London), P. Hunt, 2008, Lecture 3 Tutorial Problems

- ↑ M. Gelus, W. Kutzelnigg, Theoret chim Acta, 1973, 28, pp. 108

- ↑ D. Goutier, L.A. Burnelle, Chem Phys Lett, 1973, 18, pp. 462

- ↑ Trans Mo complex (LANL2MB) = http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4645

- ↑ Trans Mo complex (LANL2DZ) = http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4646

- ↑ Cis Mo Complex (LANL2MB) = http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4647

- ↑ Cis Mo Complex (LANL2DZ = http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4648

- ↑ G. Hogarth, T. Norman, Inorganica Chimica Acta, 1997, 254, pp. 169

- ↑ Cis vibrations = http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4649

- ↑ trans vibrations = http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4650

- ↑ D.J. Darensbourg, R.L. Kump, Inorg Chem, 1978, 17, pp. 2680

- ↑ D.J. Darensbourg, R.L. Kump, Inorg Chem, 1978, 17, pp. 2681

- ↑ D. Milstein, J.K. Stille, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1978, pp. 3636

- ↑ MOs of vinyl chloride = http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4652

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4653

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4654

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-465

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4656