Rep:Mod:tb407

Module 1: Molecular Mechanics and Spectroscopy

Modelling using Molecular Mechanics

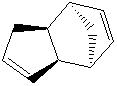

Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

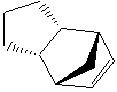

The dimerisation of cyclopentadiene can generate one of two isomers, exo and endo (1 and 2 respectively.) The energies of the two compounds are found to be 31.88 kcal mol-1 and 34.02 kcal mol-1 respectively.

These relative energies show a clear difference in the thermodynamic stability of the two compounds, namely that the exo form is more stable than the endo. It is known from experiment however, that form 2 is favoured over form 1. This suggests that this dimerisation reaction is kinetically controlled rather than thermodynamically. This selectivity is known as the endo rule[1].

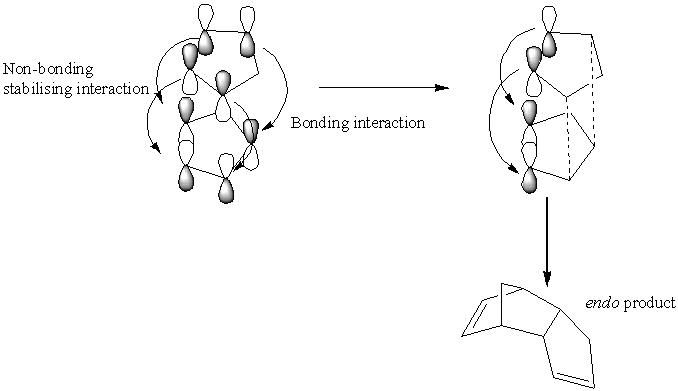

The endo rule can be rationalised in the following way. Drawing the orbitals of the two components as they come together shows the orbitals that form the new σ-bond as well as an additional set of orbitals, which can form a bonding interaction. These do not form an actual bond but stabilise the molecule in a way not present in the exo product[2] even though the exo product is more thermodynamically stable. If the reaction is reversible, the exo product product is formed.

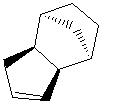

Hydrogenation of the product of dimerisation {2) can give rise to two possible isomeric products, 3 and 4, which result from hydrogenation of the two different double bonds present in the molecule.

The relative energies of 3 and 4 are 34.97 kcal mol-1 and 31.15 kcal mol-1 respectively. This suggests that the hydrogenation product 4 is more thermodynamically favoured.

The reasons for this preference for product 4 are seen when the energetics of the hydrogenation reactions are analysed closely. Table 1 gives a breakdown of the components making up the total energy.

| Component | Molecule 3 / kcal mol -1 | Molecule 4 / kcal mol -1 |

|---|---|---|

| Stretching | 1.28 | 1.10 |

| Bending | 19.09 | 14.51 |

| Torsion | 11.14 | 12.50 |

| 1,4-Van der Waals | 5.79 | 4.51 |

As can be clearly seen, isomer 3 involves much more bending energy to get from molecule 2 to the product. This dominates the other, smaller differences in energy and therefore results in the overall energy of 3 being larger than that of 4. Thus, it may be assumed that the product of hydrogenation of the cyclopentadiene dimer is molecule 4, since there is a smaller barrier to product formation.

Stereochemistry of Nucleophilic Additions to a Pyridinium Ring (NAD+ Analogues)

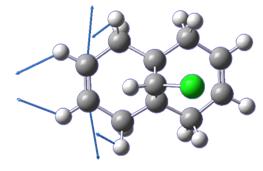

The most energetically favourable structure of the optically active prolinol derivative 5 was found using the MMFF94 force field. The relative energy was found to be 57.50 kcal mol-1. The carbonyl, while maintaining the required angles with the surrounding carbon atoms (≈120o), is not planar with the pyridinium ring as expected, but is deflected above the plane of the ring slightly. Figure 5 demonstrates that the planarity of the ring carbon is reduced (bond angles in some cases quite a way away from the ideal value of 120o), which leads to the displacement of the carbonyl above the ring.

A further conformation isomer exists, where the carbonyl group is completely coplanar with the pyridinium ring (giving rise to essentially the same energy, 57.39 kcal mol-1.) However, if the carbonyl is pushed so that it is below the ring and syn with the chiral hydrogen, energy minimisation using an MMFF94 force field restores the system to one in which the amide carbonyl and pyridinium ring are coplanar. This is line with the findings of Schultz et al[3], who stated that there are two configurations of 5, which minimise the energy (corresponding to the structures described above.)

This explains the diastereoselectivity of the reaction with Grignard reagents, which proceeds to give a molecule in which the chiral hydrogen and carbon nucleophile are anti. Addition of the Grignard yields a six-membered system, in which the Grignard is coordinated to the amide oxygen. This results in a system where the nucleophile is anti, since the carbonyl can only be directed above the molecule or be planar to the pyridinium ring.

The energy of the molecule is -2.66 kcal mol-1.

The compound 7, (fig. 7) can be seen to have an even greater displacement of the carbonyl above the ring than molecule 5.

In this case, the product of reaction with a nucleophile (aniline in this case) has the nucleophile, PhNH, syn with the chiral hydrogen (cf. anti as in the case discussed above.) This arises due to steric control originating once again from the lactam carbonyl. In this case, the carbonyl complexation blocks the top face of the molecule (since the carbonyl is deflected above the plane of the pyridinium ring) and only allows nucleophilic attack from the bottom face, syn with the chiral hydrogen[4].

The treatment of this molecule in this model is entirely based on a molecular mechanics approach, which doesn't take into account any intermolecular interactions that may occur and determine such factors as stereoselectivity. It is possible in this case to rationalise by inspection the outcome of this stereoselective reaction, but the molecular mechanics approach in itself is unable to do this. A better approach is to use semi-empirical approaches such as those applied to the treatment of the regioselective addition of dichlorocarbene.

Stereochemistry and Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

The given intermediate in the synthesis of Taxol, a chemotherapy drug, can exist as many different isomers due to the large conformational flexibility of the large ring alkene and the different forms that the cyclohexane ring can take. It is known that the most stable conformation of a cyclohexane ring is the chair form, and therefore most structures ivestigated had this conformation, although the effect of a different cyclohexane conformation on the overall energy was examined (see table 2.)

The energy of molecule 9 in an isomer with the alkenyl hydrogen trans with the bridgehead was examined using an MM2 forcefield with two different conformations of the cyclohexane ring. In the first, the ring adopted a boat-type structure and in the second, the more familiar chair conformation was adopted. The energies obtained are summarised in table 2.

| Cyclohexane conformation | Energy / kcal mol-1 |

|---|---|

| chair | 59.2664 |

| boat | 55.2337 |

As can be seen from these results, the conformation containing the cyclohexane ring in a chair conformation is more thermodynamically stable. This is exactly as expected base on knowledge of cyclohexane systems and the 1,3-diaxial interaction (ref.)

The cyclodecene ring (with a bridgehead) can take on many different conformations but the alkene can be considered to take on a configuration where the hydrogen atom points in the same direction as the carbonyl, or away from the carbonyl (see figures 8 and 9 for an illustration of this point.)

Comparison between isomers of the double bond in both molecules 9 and 10 demonstrate a preference in both compounds for a state in which the hydrogen points up (i.e. in the same direction as the bridgehead.) A summary of the relative energies of the different double bond geometries calculated using an MM2 forcefield is given in table 3. NB. all entries contain the cyclohexane ring in a chair conformation.

| Geometry of alkene H wrt bridgehead | Energy of Molecule 9 / kcal mol-1 | Energy of Molecule 10 / kcal mol-1 |

|---|---|---|

| cis | 48.3115 | 44.3115 |

| trans | 55.2337 | 49.4370 |

If the MMFF94 forcefield is used in place of the MM2, the results are as follows.

| Geometry of alkene H wrt bridgehead | Energy of Molecule 9 / kcal mol-1 | Energy of Molecule 10 / kcal mol-1 |

|---|---|---|

| cis | 60.5614 | 70.6532 |

| trans | 70.552 | 77.4316 |

Clearly, the magnitude of energy is very different depending on the forcefield used. However, if the difference in energy of the two isomers is calculated for molecule 9 using the MM2 forcefield, it can be seen to be very similar to that yielded by the calculation using the MMFF94 forcefield. On the other hand, the difference in energy of isomers for molecule 10 varies widely with the forcefield used.

| Molecule | Difference in energy of isomer using MM2 forcefield / kcal mol-1 | Difference in energy of isomer using MMFF94 forcefield / kcal mol-1 |

|---|---|---|

| 9 | 6.3428 | 6.8796 |

| 10 | 5.1198 | 10.0918 |

According to the literature[5], when it comes to comparing the conformational energies of two isomeric species such as molecules 9 & 10, the MMFF94 forcefield yields the best results. Thus, it may be reasonable to assume that the MMFF94 gives the more reliable answer in the case where the outputs by the different forcefields differ largely i.e. for molecule 10, the correct energy difference between the isomers may be assumed to be 10.09 kcal mol-1.

It is given that the hydrogenation of the alkene in molecules 9 and 10 is abnormally slow. Bredt's Rule states that double bonds to bridgehead carbons are impossible due to the inherent strain that this would involve[6] since alkene carbons need to be approximately planar (bond angle of 120o) and this is very hard to achieve in bridgehead carbons. Thus theoretically these compounds should not exist at all, or should at least be extremely reactive alkenes. However, in medium-sized cyclic bridgehead alkenes, the strain energies are less than those of the corresponding alkanes[7]. This is a phenomenon known as "hyperstability" and accounts for the fact that molecules 9 and 10 are unreactive at the alkene bond. It only occurs in rings of at least nine carbons[8].

Modelling Using Semi-Emperical Molecular Orbital Theory

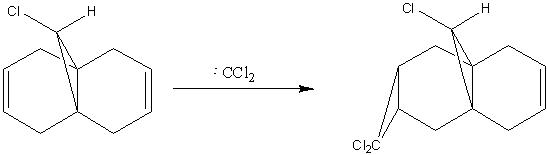

Regioselective Addition of Dichlorocarbene

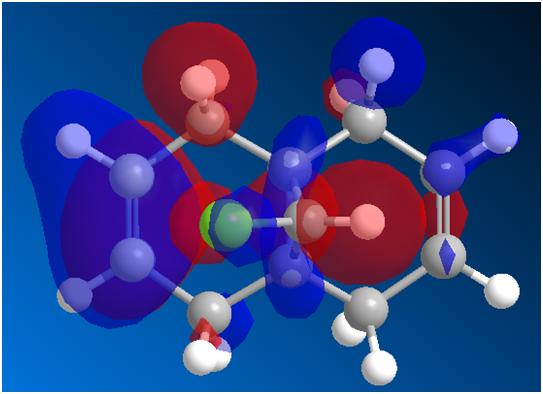

In this example, the MM2 forcefield is used to minimise the energy of the molecule shown in figure 10 and then the semi-empirical method MOPAC/PM6 is used to generate the visualisation of the molecular orbital wavefunctions in order to predict the reactivity of the compound.

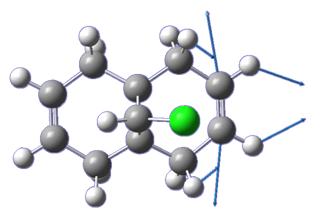

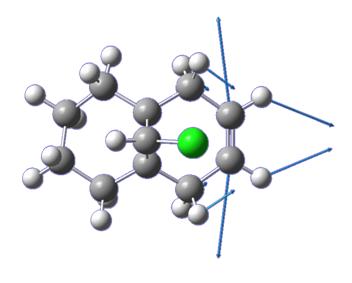

The HOMO was calculated and demonstrated to have the form shown below.

The alkene bond on the side of the molecule with the chlorine atom shows more localised electron density over the two carbon atoms. On the hydrogen side of the molecule, the electron density on the alkene can be seen to be much less. This reduced electron density may then lead us to the conclusion that the alkene bond on the side of the molecule with the chlorine atom is more nucleophilic i.e. more susceptible to electrophilic attack and reaction with dichlorocarbene. This assumption is in line with experimental observations[9].

The reason for the difference in the size of the molecular orbital coefficients on the two alkenes may be due to the distortion observed in the exo ring (on the same size as the hydrogen atom.)[10]

The HOMO-1, LUMO, LUMO+1 & LUMO+2 MO's have also been calculated (fig. 12-15.)

Using the MOPAC/PM6 optimised geometry, the compound was submitted for B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) geometry optimization and frequency calculation. The alkene C=C stretches and C-Cl stretch are listed and illustrated below (left to right: C-Cl stretch [770.84 cm-1], C=C stretch [1736.99 cm-1], C=C stretch [1757.42 cm-1].)

| Bond stretch | Wavenumber / cm-1 |

|---|---|

| C-Cl | 770.84 |

| C=C (1) | 1736.99 |

| C=C (2) | 1757.43 |

The two stretching modes for the C=C bonds are a little higher in wavenumber than expected for alkene double bonds (usually in range 1620-1680 cm-1)[11] but not too much. The wavenumber for the C-Cl stretch is in good agreement with the expected value (600-800 cm-1.)[12]

A similar treatment was given to the product of hydrogenation of molecule 12 on the exo alkene.

| Bond stretch | Wavenumber / cm-1 |

|---|---|

| C-Cl | 774.95 |

| C=C | 1758.05 |

The wavenumbers have not changed significantly with the loss of the exo alkene group. The only difference is that one of the two C=C stretching modes has vanished from the IR spectrum. Thus it can be rationalised that the 1736.99 cm-1 stretch was due to the endo C=C bond. This makes sense if one considers the bond strengths. A lower wavenumber implies a weaker bond and analysis of the MO's has already told us that the endo alkene bond is more reactive and hence more easily broken. This is then refelected in the wavenumbers of the two alkene stretches.

The predicted IR spectra of the two molecules are given in figures 16 and 17.

Structure Based Mini Project using DFT-based Molecular Orbital methods

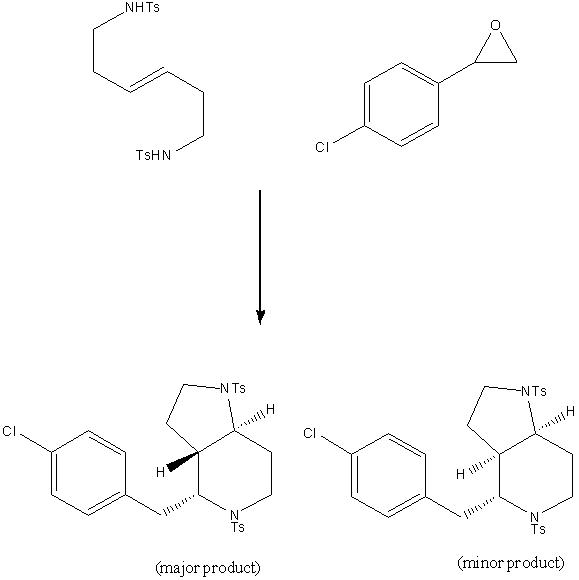

Coupling of Aryl epoxides with (E)-hex-3-ene-1,6-ditosylamide

The reaction of aryl epoxides with (E)-hex-3-ene-1,6-ditosylamide in the presence of p-TSA in dichloroethane can, in principle, give two isomeric products, one in which the two hydrogens on the fused ring aretrans (major product) and another where they are cis (minor product.)[13] These two isomers are easily differentiated by their 1H NMR spectra and coupling constants.

The energies of the two isomers were calculated using the MM2 and MMFF94 forcefields.

| Isomer | Energy using MM2 / kcal mol-1 | Energy using MMFF94 / kcal mol-1 |

|---|---|---|

| trans | 26.4048 | 5.26361 |

| cis | 26.4048 | 1.73082 |

The MMFF94 gives the more accurate energies generally. The outcome of this reaction would seem to be a surprise, since the relative energies imply that the cis geometry is the more thermodynamically favourable.

However, the geometry of the final product can be largely controlled using the starting alkene geometry. If an E alkene is used, the trans product forms more readily, if a Z alkene is used, the cis product forms more readily.[14]. Once formed, it is impossible for the molecule to change conformation to give the opposite form, since this would involve very high energy twisting in the molecule (cf. cis and trans-decalin, which cannot interconvert since the inherent strain in doing so is simply too great.) Thus, when an E alkene is used, the product formed is predominantly trans even though the cis form may be more stable.

trans form: File:Optimised3c molfile tb407.mol

cis form: File:Molecule 3d full Ts tb407.mol

The coupling constant between the hydrogens on the fused rings is reported by Yadav et al to be 12.4 Hz[15] (confirming the trans nature.) Using the optimised geometry of this molecule (using the MPW1PW91 method) in Janocchio (in MDL Molfile form), the coupling constant is reported to be 10.3677 Hz. This is in reasonable good agreement with the experimental data. In contrast with this strong coupling constant, the isomer in which the hydrogens are cis is reported to only have a 3JHH coupling constant of 6.5 Hz[16]. The cis form has not been optimised using the MPW1PW91 method. However, modelling the compound on ChemBio3D and then analysing the coupling constant between the same hydrogens using Janocchio yields a 3JHH coupling constant of 5.0281 Hz, still in relatively good agreement with the literature value of 6.5 Hz.

13C NMR data

The 13C NMR data was calculated by first optimising the geometry of a sketched structure using the MPW1PW91 method and then submitting this optimised geometry for chemical shift calculation using the same method.

This yielded the spectrum shown in figure 18, which compares reasonable well generally with the literature spectrum[17].

The chemical shifts calculated are as follows:

δ / ppm (CDCl3): 144.646 (lit. 143.8[18]), 138.134 (lit. 143.2), 137.351 (lit. 136.9), 136.408 (lit. 135.8), 135.189 (lit. 135.8), 131.395 (lit. 130.1), 129.794 (lit. 129.8), 129.682 (lit. 129.5), 128.974 (lit. 128.5), 127.472 (lit. 127.4), 127.013 (lit. 126.7), 62.0477 (lit. 58.1), 61.6525 (lit. 57.1), 51.3273 (lit. 47.9), 47.7782 (lit. 46.9), 39.0401 (lit. 39.4), 35.6122 (lit. 32.8), 31.0732 (lit. 31.4), 26.1019 (lit. 26.0.)

As can be seen, the predicted and literature 13C NMR spectra are in good agreement with one another most of the time. However, there are two chemical shifts present in the literature that are not present in the calculated spectrum. This may simply be due to not quite correct correlation of the experimental and calculated NMR spectra (at points, there are many peaks crowded together.) Furthermore, the calculated chemical shift can be quite strongly affected by the atom to which the carbon is bound. In the literature there is no assignment for the peaks and therefore it is hard to judge which peaks in the resultant spectrum will be showing this effect and to thus correct for it. Due to the fact that this paper is so recent, there are also no other spectra to cross reference the predicted spectrum with in order to find out the assignments of each shift. It is also important to bear in mind that the NMR chemical shift calculations are highly dependent on the conformation of the structure run. Thus if the actual geometry of the compound differs from that predicted by the program used, which may well be the case, this could explain why the chemical shifts calculated may be different from experimental values.

The graph below demonstrates how the calculated chemical shift varies with experimental shift.

The x-axis is arbitrarily numbered values of (δcalc - δexp) where δcalc is the value for δ calculated and δexp is the experimental value. The average modulus of the difference is found to be 1.74 ppm. This compares very favourably with values found by authors applying the same methods in different calculations (difference = 1.9 ppm[19].) The maximum deviation however was higher than that reported in the same journal, at +5.089 ppm (vs. 3.8ppm.)

13C NMR chemical shift data has been published to the digital repository[20].

IR data

The IR spectrum of the compound was run using a geometry optimised model in the B3LYP method described previously. However, since this calculation runs very slowly for very large molecules. the tosyl groups on the ring nitrogens were replaced with hydrogens for the purposes of the calculation.

The literature gives the principle IR peaks at 661 cm-1, 810 cm-1, 1089 cm-1, 1156 cm-1, 1305 cm-1 and 2925 cm-1[21]. The calculation returned frequencies at 642.453, 811.329, 1090.76, 1149.69, 1302.16 and 2900.51 cm-1. These values are in good agreement with those reported in the literature. Visualisation of these frequencies also allowed for easy identification of the different vibrations. The peaks at 661 and 810 cm-1 corresponded to aromatic ring CH bends and ring puckering. This is in line with what we intuitively know from analysing IR spectra. The peaks at 1089, 1156 and 1305 are harder to analyse, since they inolve much more motion of the molecule as a whole, which is necessary in order to keep the centre of mass in place and stop the molecule translating through space. They do, however, all seem to be a mixture of C-N bends and CH bends. The final vibration at 2925 cm-1 corresponds to a very strong stretch in the C-H bonds at the fused hydrogen rings. Although the calculation reports two separate vibrations, one for the CH syn to the aromatic group and the other for the CH anti, it is unlikely that the IR spectrum reported in the literature can resolve these two close signals and that therefore the observed peak is actually a combination of these stretching modes. It is important to remember that the calculations of stretching frequencies in the molucule was approximated by replacing tosyl groups with hydrogen atoms, for ease of calculation. Although the agreement is still quite good, this does mean that there are some peaks appearing in the predicted spectrum which will not be present in the literature spectrum and vice versa. For example, there are some strong NH stretching frequencies in the predicted spectrum which are not present in the true spectrum, simple because the bonds are not present. Simililarly the bulky tosyl groups may actually interact with the molecule in such a way as to diminish certain other vibrations, which are observed in the predicted spectrum (fig. 19.)

IR data has been published to the digital repository[22]

Circular Dichroism data and Optical Rotation Data

Circular dichroism and optical rotation data were obtained and placed in the digital repository. It has not been analysed here and now, due to the fact that currently no reference data for comparison has been obtained. It has been run and placed in the digital repository for future reference[23][24].

References

- ↑ J. Clayden, N. Greeves, S. Warren, P. Wothers, in Organic Chemistry, Oxford University Press, 6th edn, 2007, pp.912

- ↑ J. Clayden, N. Greeves, S. Warren, P. Wothers, in Organic Chemistry, Oxford University Press, 6th edn, 2007, pp.916

- ↑ A.G. Shultz, L. Flood, J. P Springer, J. Org. Chem., 1986, 51, pp. 839

- ↑ S. Leleu, C. Papamicael, F. Marsais, G. Dupas, V. Levacher, Tetrahedron-Asymmetr, 2004, 15, pp.3922-3923

- ↑ T.A. Halgren, J. Comput. Chem., 1998, 20, pp. 745

- ↑ J. Clayden, N. Greeves, S. Warren, P. Wothers, in Organic Chemistry, Oxford University Press, 6th edn, 2007, pp.484

- ↑ W.F. Maier, P. v Rague Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103, pp. 1891

- ↑ A.B. McEwan, P. v Rague Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1986, 108, pp. 3958

- ↑ B. Halton, S.G.G. Russell, J. Org. Chem., 1991, 56, pp.5553

- ↑ B. Halton, R. Boese, H. Rzepa, J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2, 1992, pp. 447-448

- ↑ P. Atkins, J. de Paula, in Physical Chemistry, Oxford University Press, 8th edn, 2006, pp.1013

- ↑ P. Atkins, J. de Paula, in Physical Chemistry, Oxford University Press, 8th edn, 2006, pp.1013

- ↑ J.S. Yadav, P. Borkar, P. Pawan Chakravarthy, B.V. Subba Reddy, A.V.S. Sarma, S Jeelani Basha, B. Sridhar, R. Gree, J. Org. Chem., 2010, pp. 1

- ↑ J.S. Yadav, P. Borkar, P. Pawan Chakravarthy, B.V. Subba Reddy, A.V.S. Sarma, S Jeelani Basha, B. Sridhar, R. Gree, J. Org. Chem., 2010, pp. 1

- ↑ J.S. Yadav, P. Borkar, P. Pawan Chakravarthy, B.V. Subba Reddy, A.V.S. Sarma, S Jeelani Basha, B. Sridhar, R. Gree, J. Org. Chem., 2010, Supplementary Material, S5

- ↑ J.S. Yadav, P. Borkar, P. Pawan Chakravarthy, B.V. Subba Reddy, A.V.S. Sarma, S Jeelani Basha, B. Sridhar, R. Gree, J. Org. Chem., 2010, Supplementary Material, S7

- ↑ J.S. Yadav, P. Borkar, P. Pawan Chakravarthy, B.V. Subba Reddy, A.V.S. Sarma, S Jeelani Basha, B. Sridhar, R. Gree, J. Org. Chem., 2010, Supplementary Material, pp. 4

- ↑ J.S. Yadav, P. Borkar, P. Pawan Chakravarthy, B.V. Subba Reddy, A.V.S. Sarma, S Jeelani Basha, B. Sridhar, R. Gree, J. Org. Chem., 2010, Supplementary Material, S15

- ↑ S.D. Rychnovsky, Org. Lett., 2006, 8, pp. 2896

- ↑ 13C NMR chemical shift Digital repository address: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4342

- ↑ J.S. Yadav, P. Borkar, P. Pawan Chakravarthy, B.V. Subba Reddy, A.V.S. Sarma, S Jeelani Basha, B. Sridhar, R. Gree, J. Org. Chem., 2010, pp. 4

- ↑ IR spectrum Digital repository address: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4343

- ↑ Optical Rotation Digital Repository Address: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4344

- ↑ Circular Dichroism Digital Repository Address: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4345