Rep:Mod:tb12

Introduction

Computational chemistry can be used as a tool to rationalise the outcome of a reaction based on the structure of both the reactants and the products, notably to explain the stereochemical outcome of reactions where more than one product is possible. The use of chemical modelling can then be extended further to predict the outcome of various reactions with high levels of success. This can be useful to the chemist in confirming and explaining the results of real reactions. Modern methods (e.g. molecular mechanics approaches) are particularly useful because the calculations avoid the use of the Schrodinger equation and take very little time.

Modelling Using Molecular Mechanics

The Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene

Cyclopentadiene could dimerise to give either an exo or an endo product. A study of both structures using an MM2 force field reveals the energy of the exo (1) dimer to be slightly lower (31.9 kcal/mol) than the corresponding endo (2) dimer (34.0 kcal/mol). However, it is known that 2 is produced specifically, indicating that the cyclodimerisation reaction is kinetically controlled. If it were thermodynamically controlled, then the more stable product would be formed in preference (the exo dimer, because it is lower in energy).

Controlled hydrogenation of the endo product can give one of two dihydro products: 3 or 4, depending on which of the double bonds is hydrogenated. Further hydrogenation would form the tetrahydro derivative. 4 is lower in energy (31.2 kcal/mol) than 3 (35.9 kcal/mol), therefore it is expected to be the less strained compound and the thermodynamic product.

| Product | Stretching | Bending | Strech-Bend | Torsion | VDW | Dipole-Dipole | Total Energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 1.2 | 19.0 | -0.8 | 12.1 | 4.2 | 0.2 | 35.9 |

| 4 | 1.1 | 14.5 | -0.5 | 12.5 | 3.5 | 0.1 | 31.2 |

Stereochemistry of Nucleophilic Additions to a Pyridinium Ring (NAD+ analogue)

The optically active derivative of prolinol (5) will react with a Grignard reagent to alkylate the pyridine ring at the four position with specific stereochemistry (product 6). The reactant has been modelled in ChemBio3D Ultra and the energy minimised using an MM2 force field. In the optimization process, it is possible to generate a large variety of models, with a huge range in energy, depending on the starting point used. The highest energy molecules (with an energy > 100 kcal/mol) feature the amide oxygen atom pointing back into the seven-membered ring. The lowest energy model found had an energy of 42.8 kcal/mol. In this case, the carbonyl was almost planar to the aromatic ring.

In all of the low energy conformations (with a minimised energy < 45 kcal/mol), the carbonyl is either planar to the pyridine ring, or is positioned above the plane of the ring. The main variation between them involves the arrangement of atoms in the seven-membered ring - especially the relative stereochemistry of the oxygen atom.

The structure of 5 can explain the stereo- and regiochemistry seen in the final product when the mechanism is considered. The mechanism involves the Grignard reagent coordinating to the amide carbonyl as seen below[1]:

Because the amide oxygen is pointing out of the plane of the aromatic ring, the Grignard reagent must attack from above the plane of the ring. This means that the methyl group must add from above as well, creating the stereochemistry displayed in the mechanism. The addition is at the four position (para to the N+) because it is the only atom in the ring close enough in proximity to the Grignard reagent once it has coordinated, without steric hindrance from the seven-membered ring structure.

The program will not run the minimization when the MeMgI molecule is present. The following error message occurs: 'No atom type was assigned to the selected atom', with the magnesium atom highlighted. The program seems unable to deal with metal atoms.

Pyridinium ring 7 can react with aniline to form product 8, where -NHPh has been added at the four position. In order to explain the stereo- and regiochemistry of the reaction, the structure of 7 has been looked at using molecular mechanics in the same manner as reactant 5.

Reactant 7 has the potential to form a wide range of conformers. Several of these conformers are clearly unfeasible because they are very high in energy e.g. conformers with a highly distorted seven-membered ring and a carbonyl group pointing back towards the ring structure. The conformer discovered to have the lowest total energy is featured below, found to have an energy of 63.5 kcal/mol. Several other slight variations of this had a similar total energy, with differences in the angle of the methyl group attached to the seven-membered ring. The energy values of 7 are in general larger than the values seen for 5. This is due to the increased size of the molecule leading to steric clashes (e.g. the i-Pr group), and the proximity of several rings that are conformationally inflexible and increase the strain.

As in the previous example, the stereochemistry of the product is again dependent on the positioning of the carbonyl group [2]. However, in this case the addition occurs on the face opposite to the one that the oxygen atom is pointing in. The reason for this is steric control. Although the amide oxygen is again responsible for directing the addition at the para position, both the nitrogen and oxygen atom have lone pairs and in order to minimise repulsion between them, the -NHPh group will add to the opposite face.

Stereochemistry and Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

Compounds 9 and 10 are isomers of an intermediate in the synthesis of Taxol. The structures differ in the orientation of the carbonyl group (in 9, it points upwards; in 10, it points downwards). Specifically, they are atropisomers, in that there is hindered rotation around a single bond - caused in this case by the conjoining ring systems. This strain barrier is high enough to allow the isomers to be isolated, but when left to stand they will convert to the more stable isomer.

Isomer 9 |

.....,..

Isomer 10 |

Isomer 9.......................................... Isomer 10

Calculated Energy: 46.4 kcal/mol...... Calculated Energy: 44.3 kcal/mol

An MM2 force field has been used to optimise the geometry and calculate the energy of both isomers. The program found the second isomer to be slightly lower in energy and therefore the more stable product. This can be explained by looking at the conjoining cyclohexane ring. In 10, the ring is positioned in the familiar, low energy chair conformation. However, in isomer 9 the ring is forced into the twist-boat conformation, which is known to be of higher energy[3]. Attempts to convert between both cyclohexane conformers proved fruitless; upon energy minimisation both isomers reverted back to the structures seen above.

The intermediate reacts abnormally slowly due to a concept known as hyperstability. An alkene is considered to be hyperstable if it has a negative olefin strain energy[4]. The isomers need to be compared to the hydrogenated versions in order to determine if this is the case. The fully saturated analogues of 9 and 10 will be referred to as 9h and 10h.

| Molecule | Stretching | Bending | Strech-Bend | Torsion | Non 1,4-VDW | 1,4-VDW | Dipole-Dipole | Total Energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 2.5 | 10.8 | 0.3 | 20.9 | -1.8 | 13.5 | 0.1 | 46.4 |

| 10 | 2.5 | 10.7 | 0.3 | 19.8 | -1.4 | 12.6 | -0.2 | 44.3 |

| 9h | 2.7 | 12.5 | 0.6 | 21.4 | -1.5 | 15.0 | 0.0 | 50.7 |

| 10h | 3.1 | 18.0 | 0.7 | 23.3 | 0.8 | 16.7 | 0.0 | 62.7 |

The olefin strain energies are -4.3 kcal/mol for 9, and -18.4 kcal/mol for 10. Both of these values are negative, therefore confirming the intermediate as a hyperstable alkene that will not be hydrogenated, even under drastic catalytic conditions[4].

Using the MMFF94 force field produces much larger values in all cases. Also, the pattern seen here is different than with the MM2 force field - in this model, isomer 9 has a lower energy than 10. However, this field is expected to be less accurate because it is primarily designed for the study of biological molecules such as proteins.

| Product | Total Energy (MMFF94)/ kcal/mol |

|---|---|

| 9 | 65.3 |

| 10 | 66.2 |

| 9h | 71.2 |

| 10h | 88.4 |

Modelling Using Semi-Empirical Molecular Orbital Theory

Compound 12 will react with electrophilic reagents such as dichlorocarbene. Rather than just taking a classical molecular mechanics approach, quantum mechanics will also now be taken into account when considering these reactions.

12 can be seen below, as optimised in an MM2 force field.

Compound 12 |

Total Energy = 17.9 kcal/mol

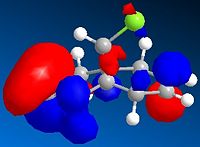

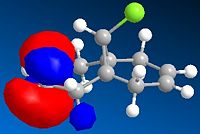

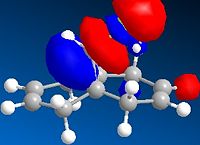

The molecular orbitals have been modelled using a MOPAC/PM6 method, and the HOMO-LUMO region is displayed below. The field gave a heat of formation value of 19.7 kcal/mol- close to the energy found using the MM2 field.

|

|

|

|

|

HOMO-1 |

HOMO |

LUMO |

LUMO+1 |

LUMO+2

|

This graphical depiction shows clearly that the alkenes are not identical. Most of the electron density is situated on the same side of the molecule that the chlorine atom is on. This is therefore the olefin that will undergo electrophilic attack, as it is the most nucleophilic.

Molecule 12h is the hydrogenated analogue of molecule 12, with the double bond anti to the C-Cl bond (the less nucleophilic double bond) having been replaced by a single bond. Initial MM2 molecular mechanics gave 12h as having a total energy of 22.3 kcal/mol. 12 and 12h were both put through a B3LYP/6-31 Gaussian geometry optimisation and frequency calculation.

The dihydro derivative shows a slight shift to higher frequencies than the initial diene. Although the C=C frequencies are of low intensity, they are known to appear in the region below 2000 cm-1 and therefore can be ascribed as below:

| C-Cl /cm-1 | C=C /cm-1 | |

|---|---|---|

| 12 | 771 | 1739, 1757 |

| 12h | 775 | 1758 |

The existence of two C=C stretching frequencies confirms that the double bonds are not equivalent. The peak at 1739 cm-1 can be attributed to the anti double bond because it is no longer present in the spectrum of the alkene. The wavenumber of the C-Cl peak has increased upon hydrogenation, therefore also increasing in energy. This is due to the loss of the double bond, which provides a stabilising influence in the diene. The occupied exo C=C π orbital has an antiperiplanar relationship to the Cl-C σ* orbital, which is known to lower the energy of the bond[5]. This also helps to explain why the endo double bond is more reactive and hence more nucleophilic.

Structure Based Mini-Project using DFT-Based Molecular Orbital Methods

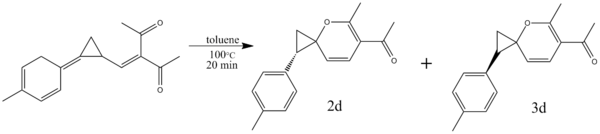

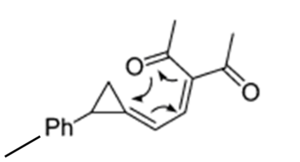

Spiro[2.5]octa-3,5-dienes can be formed from methylenecyclopropane methylene diketone derivatives as seen below[6]:

This thermally induced electrocyclic reaction has the potential to form either a trans (isomer 2d) or a cis (isomer 3d) product. The exact ratio of the products is dependent on the group attached to cyclopropane ring in the product - in this particular example, the group is -p-PhMe, and the ratio is 2.3:1[6].

It is possible to predict the 13C NMR spectrum of both products using the GIAO approach. In preparation for this, the molecules were first geometrically optimised using MM2 mechanics and then through a Gaussian procedure (MPW1PW91). These minimisations yielded total energies of 24.5 kcal/mol (2d) and 24.9 kcal/mol (3d). This would appear to show that 2d is more stable (which fits the experimental results), although the energy difference is not so great to preclude the formation of 3d. The stability can be rationalised by considering the sterics of the isomers. The cis product features the methylphenyl group pointing back towards the molecule - towards the lone pairs on the oxygen and towards the methyl group, resulting in a greater steric clash, particularly because the phenyl group is relatively bulky. The resultant predicted NMR spectra can be seen here.[7][8].

| 2d: Calculated Chemical Shift / ppm | 3d: Calculated Chemical Shift / ppm | 2d: Exp. Chemical Shift / ppm[6] |

|---|---|---|

| 194.8 | 196.0 | 196.1 |

| 168.3 | 170.0 | 166.7 |

| 130.0 | 131.2 | 136.0 |

| 126.8 | 128.0 | 132.8 |

| 124.8 | 126.1 | 129.0 |

| 123.1 | 124.3 | 128.4 |

| 122.5 | 123.7 | 123.2 |

| 119.5 | 120.7 | |

| 118.5 | 119.7 | 116.2 |

| 113.0 | 114.3 | 113.8 |

| 109.7 | 111.0 | |

| 67.9 | 69.2 | 65.1 |

| 35.4 | 36.7 | 31.1 |

| 27.1 | 28.4 | 29.3 |

| 22.3 | 23.5 | 21.0 |

| 20.5 | 21.7 | 20.5 |

| 19.4 | 20.7 | 19.7 |

There is a very good correlation between the values found in literature and the values predicted by the Gaussian procedure, indicating that the method is reasonable to use in this instance. The values do not need to be corrected because there are no heavy atoms present in the molecule. The isomers have very similar spectra. They have all the same peaks, which is to be expected because the structure is almost entirely the same. There are the same number of peaks as there are carbon atoms. The main difference is that the chemical shifts are at slightly higher ppm values for the cis isomer.

Along with NMR spectra, it is possible to calculate predicted IR spectra using Gaussian. The IR spectra look the same, as would be expected. The stereochemistry has no effect on the bond stretching in this case.

To conclude, the close correlation between the predicted NMR spectra and the experimental spectrum suggests that the isomeric products described in the literature were indeed the correct products. This can be accounted for by considering the stability of both isomers, and by taking note of the sterics involved in the pericyclic process of formation.

References and Citations

- ↑ A. G. Shultz, L. Flood and J. P. Springer, J. Org. Chemistry, 1986, 51, 838. DOI:10.1021/jo00356a016

- ↑ S. Leleu, C.; Papamicael, F. Marsais, G. Dupas, V.; Levacher, Vincent. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, 2004, 15, 3919-3928. DOI:10.1016/j.tetasy.2004.11.004

- ↑ S. W. Elmore and L. Paquette, Tetrahedron Letters, 1991, 319; DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 P. Camps, F. Perez, S. Vazquez, Tetrahedron, 1997, 53, p.9727-9734; DOI:10.1016/S0040-4020(97)00595-4

- ↑ B. Halton, R. Boese and H. S. Rzepa., J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 2, 1992, 447. DOI:10.1039/P29920000447

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 X. Tang, Y. Wei, M. Shi; Org. Lett., 2010, 12, p.5120-5123; DOI:10.1021/ol102002f

- ↑ SPECTRa Chemical Depository: Product 2d DOI:10042/to-5675

- ↑ SPECTRa Chemical Depository: Product 3d DOI:10042/to-5683