Rep:Mod:ss7009module3

SNEHA SHAH: Computational Lab Module 3

This module is based on using computational methods to investigate the transition structures in larger molecules. This module requires deeper computational methods which describe bonds being made and broken, and changes in bonding type/electron distribution [1]. The molecular mechanics/force field methods which have been previously applied for structure determination cannot be used here (in general).

Calculations conducted in this module will be run on GaussView 5.0.9. They are based on using molecular orbital methods, numerically solving the Schrodinger equation and locating the transition structures based on the local shape of a potential energy surface[1]. Alongside the determination of the transition structure, computational chemistry can also provide useful information such as reaction paths and activation barrier heights.

The Cope Rearrangement Tutorial

The Cope Rearrangement Tutorial uses 1, 5 hexadiene as an example of how to study a chemical reactivity problem. The sigmatropic reaction shown in Figure 1, involves the concerted migration of an atom from one point of attachment to a conjugated system to another point of attachment, during which one σ bond is broken and one σ bond is made [2]. The Cope rearrangement follows this concerted route via a transition state. The objective of this tutorial is to rationalize the preferred reaction mechanism by using computational methods to locate the low energy minima and transition structures on the potential energy surface of the diene [1].

The product of the Cope rearrangement can be found in the “chair” and also the “boat” conformation. Computational calculations will be used to show the “chair” and higher energy “boat” transition state.

Reactants and Products Optimization

The “Anti 2” structure of 1-5 hexadiene was originally created on GaussView and then cleaned. The “anti” conformation indicates an anti-periplanar conformation. An optimisation calculation was carried out for C6H10. This involved altering the molecular geometry to an energy minimum. The following criterion was followed for the calculation for the optimised geometry:

- Method: Hatree-Fock (HF)

- Basic Set: 3-21G

- Type of Calculation: OPT (Optimization)

- %mem: 250 MB

The method determines the type of approximations that are made in solving the Schrodinger equation [1]. There are different basis sets which can be used, which correspond to the accuracy of the calculation. 3-21G has a very low accuracy; however, this indicates that the calculations are very quick [1], enabling the optimization to be run on Gaussian. The structure of the “Anti 2” conformation is shown below(Figure 2), highlighting the energy of the molecule and the corresponding point group. Figure 3 [3] illustrates the low energy conformations of butane are the anti-periplanar and gauche form. This butane example also correlates for 1, 5 hexadiene. Therefore, it can be predicted that the anti-periplanar conformation will be the lowest energy conformation. This hypothesis will now be tested. All the low energy anti-periplanar and gauche conformers have been created by altering the dihedral angle of the central four carbon atom. They have been optimized and tabulated using the same method as for the "Anti 2" conformation, shown in Figure 2.

| Conformers of 1,5 -hexadiene | ||||||

| Conformer | Structure | Jmol Preview | Point Group | Energy/Hatrees (HF/3-21G) | Relative Energy/ kcal/mol | |

| Gauche 1 |  |

C2 | -231.68772 | 3.10 | ||

| Gauche 2 |  |

C2 | -231.69167 | 0.62 | ||

| Gauche 3 |  |

C1 | -231.69266 | 0.00 | ||

| Gauche 4 |  |

C2 | -231.69153 | 0.71 | ||

| Gauche 5 |  |

C1 | -231.68962 | 1.91 | ||

| Gauche 6 |  |

C1 | -231.68916 | 2.20 | ||

| Anti 1 [1] |  |

C2 | -231.69260 | 0.04 | ||

| Anti 2 [2] |  |

Ci | -231.69254 | 0.08 | ||

| Anti 3 [3] |  |

C2h | -231.68907 | 2.25 | ||

| Anti 4 [4] |  |

C1 | -231.69097 | 1.06 | ||

Figure 2 shows that the lowest energy conformation of 1, 5 hexadiene was calculated as “Gauche 3”. The energy of this structure has been used as a reference and set to 0.00 kcal/mol. The relative energy in kcal/mol of every other conformation has been calculated with respect to this reference. This calculation does not agree with the prediction stated above. This prediction is based on three effects which contribute to stabilising the energy of the conformer:

Effect 1: Orbital overlap or bond orientation: This effect is associated with an interaction between a pair of electrons in the σ C-H bonding orbital and the vacant σ* anti bonding orbital. The result is stabilization of the filled bonding NBO (by an energy E2) and destabilization (by an energy >E2) of the antibonding NBO. Since the latter has no electrons, the overall effect is of stabilization. The more favourable the orbital alignment, the greater the interaction and in turn, the more stabilized the conformer. Both the gauche and antiperiplaner conformer orbitals can overlap efficiently (rendering the two low energy minima); however the overlap is optimal for the anti-periplanar orientation. Effect one favours the anti-periplanar conformer [3].

Effect 2: Bond-Bond or Pauli Repulsions: The effect is associated with the interaction between two occupied σ bonding orbitals, resulting in overall destabilization. This affect is minimised for the anti-periplaner conformer. As above, effect two favours the anti-periplanar conformer [3].

Effect 3: Van der Waals (dispersion) forces: This interaction is absent for the anti-periplanar conformation. However, the 60° dihedral angle of the gauche conformation results in H…H close contacts leading to a slight increase in stabilisation energy (Figure 4). Effect three favours the gauche conformer [3].

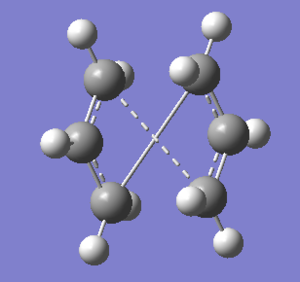

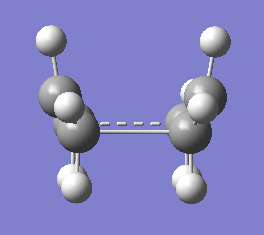

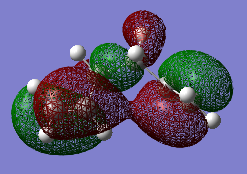

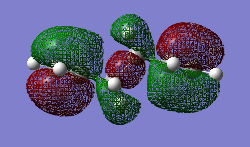

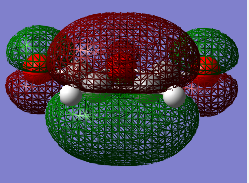

| HOMO : "Gauche 3" | HOMO : "Anti 2" |

|---|---|

|

|

Figure 4 shows the stabilizing π interaction between the terminal C=C bonds in "Gauche 3", which is absent for the anti-periplanar structures. At the HF/3-21G level of theory, this is the determining factor, rendering "Gauche 3" the most stable conformer. However, the initial is based on the fact that: Combining effect one and effect two win out over effect three, indicating that the anti-periplanar conformation is favoured. Therefore, the results produced using the HF/3-21G level of theory were assumed to be not accurate enough, as explained above. The three lowest energy conformers (“Gauche 3”, “Anti 1” and “Anti 2”) were reoptimized using a higher level of theory. The following criterion was followed for the calculation:

- Method: B3LYP

- Basic Set: 6-31G*

- Type of Calculation: OPT (Optimization)

- %mem: 250 MB

The structure of the each conformation is shown below (Figure 5), highlighting the energy of the molecule and the corresponding point group. The corresponding energy calculation formed using HF/3-21G has also been tabulated for comparison purposes.

| Conformers of 1,5 -hexadiene | ||||||

| Conformer | Structure | Jmol Preview | Point Group | Energy/Hatrees (DFT/6-31G*) | Relative Energy/ kcal/mol | Energy/Hatrees (HF/3-21G) - Comparison |

| Gauche 3 [5] |  |

C1 | -234.61133 | 0.29 | -231.69266 | |

| Anti 1 [6] |  |

C2 | -234.61179 | 0.00 | -231.69260 | |

| Anti 2 [7] |  |

Ci | -234.61170 | 0.06 | -231.69254 | |

Figure 5 correctly highlights that the anti-periplanar conformers are higher in energy than the gauche conformer, which is now in agreement with the theory. In particular, the “Anti 1” conformer is more stable than the “Anti 2” conformer by 0.0009 Ha. This indicates that when carrying out calculations on GaussView, the level of theory must be correctly defined to ensure that the results are reliable. This is a balance between the calculation time and the desired accuracy level.

| HOMO : "Gauche 3" | HOMO : "Anti 2" |

|---|---|

|

|

Analysing, the molecular orbitals as shown in Figure 6, indicates that effect 3 is still prominate. However, as predicted effect one and effect two combined must win out over effect three, rendering the anti-periplanar conformer more stable. The optimized geometry of the “Anti 2” conformer was compared between the different levels of theory in order to explain the differences in energies. However, it was found that the point group hadn’t changed, as shown in Figure 7, and there are minimal differences between dihedral angles and bond lengths between the two optimized structures. This indicates the significance of carrying out the calculation at the correct level of theory.

| Geometry Parameters | ||||||

| Conformer | Central (C-C-C-C)Dihedral Angle/° | Central (H-C-C-H)Dihedral Angle/° | End (C-C-C-C)Dihedral Angle/° | Central (C-C)Bond Length/Å | End(C=C)Bond Length/Å | |

| Anti 2 (HF/3-21G) | 180.00 | 180.00 | 114.67 | 1.55 | 1.32 | |

| Anti 2 (DFT/6-31G*) | 180.00 | 180.00 | 118.53 | 1.55 | 1.33 | |

Vibrational Analysis

A frequency calculation was carried out for each of the structures in Figure 5. This involved determining the second derivative of the potential energy surface and the IR and Raman modes to support the structures. The following criterion was followed for the calculation for the vibrational analysis:

- Method: DFT

- Basic Set: 6-31G*

- Type of Calculation: Frequency

- %mem: 250 MB

The calculation can be illustrated graphically, as shown for the “Anti 2” conformer in Figure 8. The frequencies are all real and positive indicating that a minimum has been established, which is what was requested by the program. This shows that the frequency calculation was successful. If one of the frequencies was negative, this would mean a transition state has been established and if more than one negative frequency is seen, this would mean that the calculation was not successful.

The frequency calculation allows thermochemical data to be obtained for each of the lowest energy conformers. The Freq=ReadIsotopes option in GuassView was used, with an input temperature of 0.0001K in order to rerun the calculation at 0K. Figure 9 shows the individual energy contributions computed at 298.15 K and at 0K.

Thermochemical Data

| Thermochemistry of "Anti 1" | ||||||

| Temperature/K | Sum of Electronic and Zero Point Energies/Hatrees | Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies/Hatrees | Sum of Electronic and Thermal Enthalpies/Hatrees | Sum of Electronic and Thermal Free Energies/Hatrees | ||

| 298.15 [8] | -234.469299 | -234.461968 | -234.461024 | -234.500859 | ||

| 0 [9] | -234.469299 | -234.469299 | -234.469299 | -234.469299 | ||

| Thermochemistry of Anti 2 | ||||||

| Temperature/K | Sum of Electronic and Zero Point Energies/Hatrees | Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies/Hatrees | Sum of Electronic and Thermal Enthalpies/Hatrees | Sum of Electronic and Thermal Free Energies/Hatrees | ||

| 298.15 [10] | -234.469212 | -234.461856 | -234.460912 | -234.500821 | ||

| 0 [11] | -234.469212 | -234.469212 | -234.469212 | -234.469212 | ||

| Thermochemistry of "Gauche 3" | ||||||

| Temperature/K | Sum of Electronic and Zero Point Energies/Hatrees | Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies/Hatrees | Sum of Electronic and Thermal Enthalpies/Hatrees | Sum of Electronic and Thermal Free Energies/Hatrees | ||

| 298.15 [12] | -234.468693 | -234.461464 | -234.460520 | -234.500105 | ||

| 0 [13] | -234.468693 | -234.468693 | -234.468693 | -234.468693 | ||

The sum of electronic and zero-point energies is the potential energy at 0 K including the zero-point vibrational energy (E = Eelec + ZPE) [1]. The results show that the zero point energy is not dependant on temperature and therefore, remains unchanged. This corresponds to the fact that at absolute zero, there is thermal contribution. The sum of electronic and thermal energies is the energy at 298.15 K and 1 atm of pressure which includes contributions from the translational, rotational, and vibrational energy modes at this temperature (E = E + Evib + Erot + Etrans) [1]. These contributions will increase with increasing temperature, due to an increase in entropy. The sum of electronic and thermal enthalpies contain an additional correction for RT (H = E + RT) [1]. This equation shows that as the temperature increases, the thermal enthalpy should also increase, which is consistent with the results in Figure 9. The sum of electronic and thermal free energies includes the entropic contribution to the free energy (G = H - TS) [1]. As the temperature is increased, the entropic contribution becomes more prominate indicating a more negative free energy. It is also important to note that the calculation at absolute zero shows that there are no contributions from the thermal, thermal free energies or from the thermal enthalpies. Each of these values are equal to the zero point energy. This corresponds to the fact that at absolute zero, there is no thermal contribution.

Chair and Boat Transition State Optimizations

This section will model the chair and higher energy boat transition state for the Cope Rearrangement. Each transition state consists of two C3H5 allyl fragments. Initially, the allyl fragment was constructed and optimized on GuassView using the HF/3-21G level of theory. The two allyl fragments were then orientated in order to take the form of the chair transition state, known as the “guess” structure. The bond break/forming separation distance between the two fragments was set to 2.2Å. Transition state optimizations are more complex than minimizations because the calculation needs to be able to locate the negative direction of curvature (maximum). The optimisation of the chair transition structure can be computed using two different methods, depending on how well the guess structure corresponds to the actual transition structure. A frequency calculation of the optimised transition will also be analysed in this section, one imaginary frequency would indicate a transition structure.

(1) Force Constant Matrix Method

The Force constant matrix method can be employed when the orientation of the guess transition structure is fairly accurate. This approach calculates the force constants once at the beginning of the calculation. The following criterion was followed for the calculation to optimize the geometry:

- Method: HF

- Basis Set: 3-21G

- Type of Calculation: Opt+Freq (Optimisation to a TS (Berny))

- Additional Keywords: Opt=NoEigen

- Force Constants: Calculate Once

NOTE:The additional keywords stop the calculation crashing if more than one imaginary frequency is detected during the optimization.

(2) Frozen Coordinate Method

If the guess structure is not close to the exact structure, then the curvature of the surface may be significantly different at certain points. In such cases, the Frozen Coordinate Method would be a better approach. This involves initially freezing the reaction coordinate (that is, the bonds forming/breaking); the separation distance was set to 2.2Å. The rest of the molecule was then relaxed by carrying out a minimization. The following criterion was followed for this calculation:

- Method: (Hatree Fock) HF

- Basis Set: 3-21G

- Type of Calculation: Opt (Optimization to a Minimization)

- Force Constants: Calculate Never

The reaction coordinate was then unfrozen on the optimized structure. A transition state optimization was now set up using the following criterion:

- Method: (Hatree Fock) HF

- Basis Set: 3-21G

- Type of Calculation: Opt (Optimization to a TS (Berny))

- Force Constants: Calculate Never

Figure 10 shows that only one imaginary frequency was observed for both methods indicating that a transition structure had been found. The vibration captures the two terminal carbons bending towards each other corresponding to the Cope rearrangement. This shows that the guess transition structure was correctly orientated as it was close to the actual structure. In addition, the reaction coordinate bond separation has been optimized to 2.02 Å for both methods, indicating that both approaches produce consistent results and are therefore reliable.

(3) QST2 Method

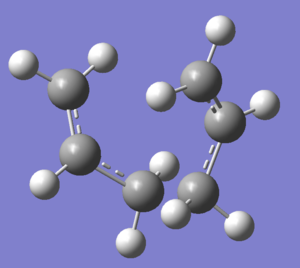

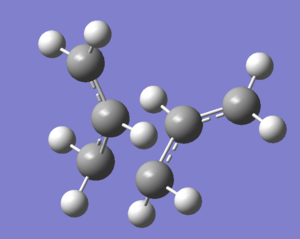

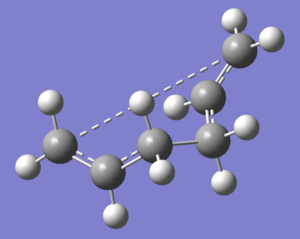

The QST2 method will be used to optimize the boat transition state. This approach allows the reactants and products to be specified for the reaction considered and the calculation set up will interpolate between the two structures to locate the transition state between them [1]. The numbering of the atoms was correlated so that the reactants and products were numbered in the same way, as shown in Figure 11. The optimization was then calculated based on the following criterion:

- Method: (Hatree Fock) HF

- Basis Set: 3-21G

- Type of Calculation: Opt+Freq (TS (QST2))

The calculation was not successful. This method carried out the interpolation linearly between the reactant and product but did not consider the possibility of rotation around the central bonds. Figure 13 shows the unsuccessful calculation, the structure appears like the chair transition structure, supported by the symmetry and geometric parameter, but more dissociated. Therefore, the geometry of the two structures needs to be altered in order for the QST2 approach to translate the allyl fragments as well as consider bond rotation. The central carbon dihedral angle was set to 0° and the inside C-C-C angle set to 100° for both structures. This orientated the reactant and product molecules closer to the boat transition structure as shown in Figure 12.

The optimization calculation was carried out again using the same criterion. This time, the calculation was successful as shown in Figure 13. The image shows a “boat-like” structure. In addition, the frequency analysis resulted in one imaginary frequency; providing further confirmation that an optimization to a transition state had occurred. Similar to the chair transition state, the vibration captures the two terminal carbons bending towards each other corresponding to the Cope rearrangement. This shows that the reactant and product structures were correctly modified, as it was closer to the actual structure.

Comparisons

Each of the three transition state optimization methods provided accurate results. However, care must be taken when using the Force Constant Matrix method or the QST2 Method, as the guess structure must already be close to the transition state. The Frozen Coordinate Method appears to be a longer approach, however, it does not present the guess structure limitation and can also save considerable amount of time when the force constant calculation is expensive.

The C-C bond distances for the reaction coordinate bonds are 2.02 Å and 2.14 Å for the chair and boat transition state respectively. In addition, the energy of the transition state is -231.61932 and -231.60280 Ha for the chair and boat form respectively. The higher (less negative) energy of the boat conformer corresponds to the eclipsed orientation of the carbon atoms on the allyl fragment. This orientation leads to unfavourable interactions and steric clashes, which are not present in the chair conformer. The boat conformer is therefore, less stable and hence higher in energy. The vibrational frequency of the boat transition state is also lower than the chair frequency, reflecting a weaker bond, supporting the statement that the chair conformer is more stable.

Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC)

Visually predicting which conformer follows which reaction path from the transitions structures is very difficult. However, preforming the IRC calculation allows the minimum energy path to be followed from the transition structure down to its local minimum on a potential energy surface, revealing the corresponding conformer [wiki]. The following criterion was followed:

- Method: Hatree Fock (HF)

- Basic Set: 3-21G

- Type of Calculation: IRC

NOTE: The reaction coordinate is symmetrical indicating that it should be computed in the forward direction only. In addition, the calculation was set so that the force constants are calculated once and the number of points along the IRC was changed from the default to 50.

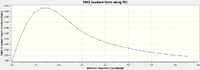

| Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate | ||||||

| Method | Image of Structure | Energy Graph | Minimum Energy / Hatrees | Gradient Graph | Gradient | |

| Chair (50 steps) [14] |  |

|

-231.68862 |  |

0.001 | |

| Chair (100 steps)[15] |  |

|

-231.68862 |  |

0.001 | |

| Chair 100 steps force constants calculated at every step)[16] |  |

|

-231.69167 |  |

0.000 | |

| Boat (100 steps and force constants calculated at every step)[17] |  |

|

-231.69266 |  |

0.000 | |

Analysis of the output file indicated that the calculation set up did not result in a minimum geometry. Figure 14 shows that a gradient of exactly 0.000 was not reached, and the energy value does not correlate to any one of the conformers in Figure 2. The calculation set up was altered so that the number of points along the IRC was increased to 100; this large number of points was assumed to be sufficient to reach a minimum. However, as Figure 14 shows a gradient of 0.000 was still not reached indicating that a minimum was not fully reached. The set up was modified again so that the force constants are computed at every step, this is the most reliable method. Figure 14 shows that the gradient reached 0.000, indicating a minimum. The energy value of this structure correlates exactly with Gauche 2 suggesting that the chair transition state connects to the Gauche 2 conformer.

The same calculation was carried out for the boat transition state, with the number of points along the IRC set to 100 and the force constants computed at every step, as this produced the most reliable results. A minimum was reached and the energy value corresponds to Gauche 3. Therefore, the boat transition state connects to this conformer. The IRC calculation is a very useful calculation implemented on GaussView as t enables the transition states to be connected to the right conformer.

Comparisons

The chair and boat transition states were reoptimized using the B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory and a frequency calculation was computed for each structure. The thermochemistry data has been tabulated at 298K and 0K in Figure 16. Further comparisons can be conducted by determining the activation energy for this rearrangement reaction via the chair transition state and boat transition state as shown in Figure 17. The activation energy has been defined as the difference between the ground state energy of 1,5 hexadiene (reactant molecule) and the transition state energy. The “Anti 2” conformer is used as the reactant molecule.

Geometric Parameters

| Geometry Parameters | ||||||

| Conformer | Chair Transition State (HF/3-21G) | Chair Transition State (B3LYP/6-31G*) | Boat Transition State (HF/3-21G) | Boat Transition State (B3LYP/6-31G*) | ||

| Point group Symmetry | C2h | C2h | C2v | C2v | ||

| C-C Bond forming/breaking Separation Distance/Å | 2.02 | 2.02 | 2.14 | 2.13 | ||

Figure 15 shows that the geometry of the transition structures was similar regardless of the level of theory employed. However, Figure 16 and 17 show that the energies of the structures are significantly different as a result of the different level of theory used.

Thermochemical Data and Activation Energies

| Energy values | |||||||

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic energy / Hatrees | Sum of electronic and zero-point energies/ Hatrees | Sum of electronic and thermal energies/ Hatrees | Electronic energy / Hatrees | Sum of electronic and zero-point energies / Hatrees | Sum of electronic and thermal energies/ Hatrees | ||

| 0 K | 298.15 K | 0 K | 298.15 K | ||||

| Chair Transition State | -231.61932 | -231.46670 | -231.46134 | -234.55698 | -234.41493 | -234.40901 | |

| Boat Transition State | -231.60280 | -231.45093 | -231.44530 | -234.54309 | -234.40234 | -234.39601 | |

| Anti 2 Conformer (Reactant) | -231.69254 | -231.53954 | -231.53257 | -234.61170 | -234.46921 | -234.46186 | |

| Activation energies | |||||||

| Method | HF/3-21G | HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | B3LYP/6-31G* | Literature [4] | ||

| Temperature | 0 K | 298.15 K | 0 K | 298.15 K | 0 K | ||

| Activation Energy (Chair) / kcal/mol | 45.70 | 44.69 | 34.06 | 33.16 | 33.5 ± 0.5 | ||

| Activation Energy (Boat) / kcal/mol | 55.60 | 54.76 | 41.96 | 41.32 | 44.7 ± 2.0 | ||

The literature values for the activation energies have been tabulated in Figure 17. This indicates that the energies computed using the HF/3-21G level of theory do not correlate to the literature values, roughly a 10kcal/mol difference. The B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory correspond well to the literature as they are within the range. This provides supporting evidence that the HF/3-21G method is not accurate enough for this investigation and a higher level of theory is required. As a consequence, it is often more computational efficient to adopt this method, that is to map the potential energy surface using the low level of theory first and then to reoptimize at the higher level. Further analysis will now be conducted with reference to the B3LYP/6-31G* results, the low level of theory will now be disregarded. It has been suggested that the boat transition state is higher than the chair due to orbital interactions between the HOMO and LUMO of the allyl fragments. This is an antibonding interaction, and therefore not favourable, resulting in a destabilizing effect. This interaction is absent in the chair transiton state [5].

The Diels Alder Cycloaddition

The Diels Alder Reaction is a common pericyclic reaction. Two π systems are involved: the diene and dieneophile. The system shown in Figure 18 is classified as a π4s + π2s cycloaddition. Whether or not the reactions occur in a concerted stereospecific fashion (allowed) or not (forbidden) depends on the number of π electrons involved [1].

The second part of this investigation focuses on the regioselectivity of the Diels Alder reaction. If the dieneophile is substituted, with substituents that have π orbitals that can interact with the new double bond that is being formed in the product, then this interaction can stabilise the regiochemistry of the reaction [1]. If both bonds are formed on the bottom face of the diene (π4s) and both bonds forming on the top face of the alkene (π2s), this is known as the exo form. An isomer in which the bonds form to the bottom face of the alkene (π2s) is known as the endo form [2]. Molecular Orbital analysis, in particular the HOMO and LUMO and studying the transition state, will be investigated to rationalize the Diels Alder Reaction.

Reactant Optimization

The cis-butadiene structure and ethylene structures were originally created on GaussView and then cleaned. An optimisation calculation was carried out for each reactant [18] [19]. This involved altering the molecular geometry to an energy minimum. The following criterion was followed for the calculation for the optimised geometry:

- Method: Semi-Empirical Molecular Orbital

- AM1

- Type of Calculation: OPT (Optimization)

Figure 19 shows the HOMO and LUMO of each reactant, indicating its symmetry with respect to the plane. The principal orbital interactions involved in the π4s + π2s cycloaddition are the HOMO/LUMO interactions of ethylene and butadiene [1]. The HOMO of ethylene interacts with the LUMO of butadiene as they are both symmetric. Similarly, the LUMO of ethylene and the HOMO of butadiene interact as they are both antisymetric. Thus it is the HOMO-LUMO pairs of orbital that interact to form the cyclohexene. Analysis of the nodal planes suggests that the matching symmetry will allow significant overlap of electron density and this indicates that the reaction is allowed. The transition state will now be modelled in order to support this prediction [1].

| HOMO Butadiene: Anti-symmetric | LUMO Butadiene: Symmetric | HOMO Ethene: Symmetric | LUMO Ethene: Anti-symmetric |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Transition State Optimization

This section will model the transition state for the Diels Alder reaction presented in Figure 18. The two previously optimized reactants were orientated in order to take the form of the transition state, known as the “guess” structure. The “guess” structure was predicted based on the fact that the transition structure has an envelope type structure, which maximizes the overlap between the ethylene π orbitals and the π system of butadiene and the ethylene approaches the cis-butadiene from above [1]. The bond break/forming separation distance between the two fragments was set to 2.0Å.

The transition state optimization method to be employed was carefully considered. Based on the advantages and disadvantages of each method, the Frozen Coordinate Method appeared to be the most suitable. This is because even though it is a longer approach, it does not present the inaccuracy of the transition structure and can also save considerable amount of time when the force constant calculation is expensive. A frequency calculation of the optimised transition will also be analysed in this section, one imaginary frequency would indicate a transition structure.

This method involves initially freezing the reaction coordinate (that is, the bonds forming/breaking); the separation distance was set to 2.0Å. The rest of the molecule was then relaxed by carrying out a minimization. The following criterion was followed for this calculation:

- Method: Semi-Empirical Molecular Orbital

- AM1

- Type of Calculation: Opt (Optimization to a Minimization)

- Force Constants: Calculate Never

The reaction coordinate was then unfrozen on the optimized structure. A transition state optimization was now set up using the following criterion:

- Method: Semi-Empirical Molecular Orbital

- AM1

- Type of Calculation: Opt (Optimization to a TS (Berny))

- Force Constants: Calculate Never

| Optimized Transition Structure | ||||||

| Jmol Preview | Imaginary Frequency/cm-1 | Image of Imaginary Frequency | Optimized bond forming/bond breaking bond length [Lit.[6]]/Å | |||

| Frozen Cooridante Method |  |

-955.90 |

| |||

Figure 20 shows that only one imaginary frequency was observed indicating that a transition structure had been found. The vibration captures the two terminal carbons bending towards each other in a concerted manner corresponding to the concerted Diels Alder Reaction. This confirms that the calculation was successful and a transition state has been located for the specified reaction.

| First Positive Frequency |

|---|

|

| 147.41 cm-1 |

The geometric parameters have also been tabulated. The bond lengths of the partially formed σ C-C bonds in the transition state are both equal at 2.12Å. This further confirms the concerted nature of the reaction. In addition, the literature Van der Waals radii of 2 carbon atoms is 3.40Å [7]. The fact that the separation between the two carbons is less than the radi indicates the partial formation of the σ C-C bonds.

The sp2 hybridised C=C bond in the transition state is actually longer than the literature value for a normal C=C bond, indicating that this bond is being lengthened in the transition state. This is consistent with the reaction mechanism shown in Figure 18, as the C=C bond rearranges to a single bond. The sp3 hybridised C-C bond in the transition state is actually shorter than the literature value for a normal C-C bond. This is what is expected again, as Figure 18 shows the single bond of the butadiene forming a double bond. The double bond of the ethane is also longer than expected as the bond is rearranging to the longer single bond.

The lowest positive frequency is shown in Figure 21. The vibration captures the two terminal carbons bending towards and away from each other in a non-concerted fashion. Comparing the two vibrations shown indicates a synchronous motion in the transition state and asynchronous motion after. The asynchronous motion cannot correspond to the transition state as the reaction mechanism occurs in a concerted manner.

Molecular Orbital Analysis

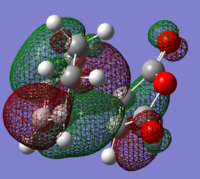

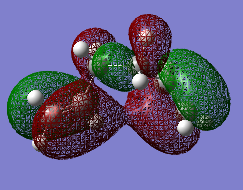

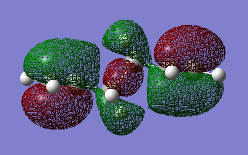

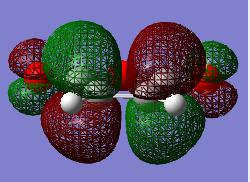

| HOMO (AM1): Anti-symmetric | LUMO (AM1): Symmetric |

|---|---|

|

|

Figure 22 shows the HOMO and LUMO of the transition state, indicating its symmetry with respect to the plane. Analysis of the nodal planes of the molecular orbitals supports the prediction stated above. The HOMO of the transition state is asymmetric with respect to the plane. This shows that the asymmetric HOMO of butadiene and asymmetric LUMO of ethene combine to form the asymmetric HOMO of the transition state. In turn, the symmetric HOMO of ethene and symmetric LUMO of butadiene combine to form the symmetric LUMO of the transition state. This combination preserves the symmetry and therefore the reaction is allowed. The opposite combinations would forbid the reaction because the orbitals have different symmetry properties and hence no overlap density is possible.

Regioselectivity of the Diels Alder Reaction

Cyclohexa-1, 3-diene undergoes a Diels Alder reaction with maleic anhydride as shown in Figure 23. This reaction is different to what has been previously examined as the substituents on the reactants can form a stabilizing interaction which can result in regioselectivity. The endo is the major, kinetic product as it has a lower activation energy than the exo form.

Reactant Optimization

This section will model the transition state for the reaction presented in Figure 23. Cyclohexa-1, 3-diene [20]and maleic anhydride [21]were initially created and optimized on GaussView 5.0.9 using the Semi-empirical AM1 method, as used in the previous section. Figure 24 shows the HOMO and LUMO of each reactant, indicating its symmetry with respect to the plane. The HOMO of maleic anhydride interacts with the LUMO of cyclohexene as they are both symmetric. Similarly, the LUMO of maleic anhydride and the HOMO of cyclohexene interact as they are both antisymetric. Thus it is the HOMO-LUMO pairs of orbital that interact to form the product. Analysis of the nodal planes suggests that the matching symmetry will allow significant overlap of electron density and this indicates that the reaction is allowed.

| HOMO Cyclohexene: Anti-symmetric | LUMO Cyclohexene: Symmetric | HOMO Maleic Anhydride: Symmetric | LUMO Maleic Anhydride: Anti-symmetric |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Transition State Optimization

The reactants were then orientated in order to take the form of the transition state, known as the “guess” structure. The bond break/forming separation distance between the two fragments was set to 2.2Å. The frozen coordinate approach was used to optimize the transition structure using the same method as employed in the previous section. A frequency calculation of the optimised transition will also be analysed in this section, one imaginary frequency would indicate a transition structure.

| Method | Jmol Preview | Energy/ Hatrees (AM1) | Imaginary Frequency/cm-1 | Image of Imaginary Frequency | Optimized bond forming/bond breaking Separation |

| Exo [22] | -0.05042 | -818.01 |  |

2.17Å | |

| Endo [23] | -0.05150 | -806.32 |  |

2.16Å |

Figure 25 shows that only one imaginary frequency was observed indicating that a transition structure had been found. The vibration captures the carbons involved in the new σ bonds bending towards each other in a concerted manner corresponding to the concerted Diels Alder Reaction. This confirms that the calculation was successful and a transition state has been located for the specified reaction.

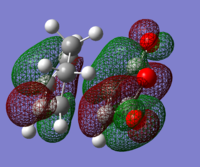

Molecular Orbital Analysis

Figure 25 shows that the endo transition state is lower than the exo form indicating that it has a lower activation barrier and hence the kinetic product. This can be explained by molecular orbital analysis. Figure 26 shows the HOMO, LUMO and LUMO+1 of the transition state, indicating its symmetry with respect to the plane. Just as in the previous section, the symmetry is preserved and therefore, the reaction is allowed. The LUMO+1 orbitals show secondary orbital effects for both forms. However, qualitatively it can be seen that this extra orbital interaction is greater for the endo form and therefore, a better interaction, rendering it the more stable transition state. In turn, the endo form has a better overlap due to the orientation of the maleic anhydride and the double bonds of the diene forming a more favourable alignment.

Intrinsic reaction Coordinate

The IRC calculation allows the minimum energy path to be followed from the transition structure down to its local minimum on a potential energy surface, revealing the corresponding product. The following criterion was followed:

- Method: Semi-Empirical

- AM1

- Type of Calculation: Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate

NOTE: The reaction coordinate is asymmetrical indicating that it should be computed in the forward and backwards direction. In addition, the calculation was set so that the force constants are calculated always and the number of points along the IRC was changed from the default to 100. Figure 27 shows that the gradient reached 0.000 for each form, indicating a minimum.

| IRC | ||||||

| Image of Structure | Energy Graph | Energy/Hatrees | Gradient Graph | Gradient | Optimized bond forming/bond breaking Separation/Å | |

| Exo [24] |  |

|

-0.15991 |  |

0.000 | 1.54 |

| Endo [25] |  |

|

-0.16017 |  |

0.000 | 1.54 |

The endo product and exo product was created and optimized on GuassView using the same level of theory to further confirm that the correct transition state had been located as shown in Figure 28. The exact energy value and bond separation distances were obtained indicating that the results are accurate.

One would assume that the exo product would be lower in energy than the endo product due to less steric strain. However, the opposite is actually observed by 0.00026 Ha. A possible reason for this could be the steric clashes between the C-C bridge and the oxygen.

| Method | Jmol Preview | Energy/ Hatrees (AM1) | Optimized bond forming/bond breaking Separation/Å |

| Exo [26] | -0.15991 | 1.54 | |

| Endo [27] | -0.16017 | 1.54 |

References

<references>

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 Third year Chemistry Computation Lab Module 3:Inorganic

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 http://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/local/organic/pericyclic/

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 http://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/local/organic/conf/

- ↑ M. J. Goldstein, M. S. Benzon, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1972, 94, 7149DOI:10.1021/ja00775a046

- ↑ I Fleming, 'Frontier Orbitals and Organic Chemical Reactions', 1st edition, 1976, pp5-10

- ↑ http://www.science.uwaterloo.ca/~cchieh/cact/c120/bondel.html

- ↑ Bondi, A. (1964). "Van der Waals Volumes and Radii". J. Phys. Chem. 68 (3): 441–51.