Rep:Mod:sp33

Cope Rearrangement

The cope rearrangement was discovered by A. Cope and E. Hardy in 1939[1]The reaction is a [3,3] sigmatropic reaction that has been proven to occur concertedly.[2]

It is generally accepted that the reaction goes via a chair or boat like transition state.

The low-energy minima and transition structures on the C6H10 potential energy surface can be found, in order to determine the preferred reaction mechanism.

optimising the reactant and product

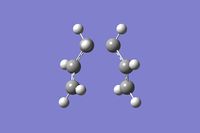

A molecule of 1,5 hexadiene (1) was drawn using gaussian with an anti linkage of the main chain. It was then optimised using the HF/3-21G method and then the energy and symmetry were recorded in the table below. A gauche conformer (2) of the molecule was also optimised and analysed. The gauche conformer was lower in energy . In order to calculate the activation energies and enthalpies the lowest energy conformer is needed. Because the Gauche conformer is lower in energy, it would make sense to try structures with more gauche conformations in them. Several structures were tried to see which was lowest in energy. They were then identified by comparing to the low energy conformers in Appendix 1 .

| conformer | Energy /a.u | Energy /Kcalmol-1 | Point Group | Conformation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

-231.69097 | -145388.28 | C1 | anti 4 |

| 2 |  |

-231.68962 | -145387.43 | C1 | gauche 5 |

| 3 |  |

-231.69260 | -145389.30 | C2 | anti 1 |

| 4 |  |

-231.69266 | -145389.34 | C1 | gauche 3 |

| 5 |  |

-231.69254 | -145389.26 | Ci | anti 2 |

The lowest energy conformation is the gauche 3 conformation followed by the anti 1 conformation. The introduction of the gauche linkage means the molecule is more stable as there are now more favorable van der Waahls interactions. The lowest three conformations were then optimised at the B3LYP/6-31G* level, as this is a more powerful technique and gives more accurate energies.

| conformer | Energy /a.u | Energy /Kcalmol-1 | input structure | output structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gauche 3 | -234.61133 | -147220.83 |  |

|

| Anti 1 | -234.61179 | -147221.12 |  |

|

| Anti 2 | -234.61171 | -147221.07 |  |

|

When calculated at this higher level the energies of the three conformers change and the anti 1 conformer is now the lowest in energy. As can be seen from the images there isn't a large difference between the structures from the two levels of optimisation.

When the reaction occurs it goes from the Ci symmetry conformer. Therefore the geometries from the two calculations can be compared directly.

| method | Bond lengths/Å and Angles /° |

|---|---|

| HF/3-21G |

|

| B3LYP/6-31G* |

|

The bond lengths are very similar but the angles are relatively different. with the B3LYP structure being slightly more linear.

The frequency analysis of this conformer was performed to ensure that a true minima had been found.

As can be seen in the spectra, there are no negative vibrations, so it is confirmed that an actual minima has been found as oppose to a transition atate maxima.

The various energies of the system are also calculated using this method. The sum of the electronic and zero point energies is the potential energy at 0K. The sum of electronic and thermal energies gives the energy at 298.15K and 1 atmosphere. It contains contributions from the translational, rotational and vibrational energies. The third gives the enthalpy and takes into a correction for room temperature as H = E + RT. The fourth is the energy with the entropic contribution to the free energy considered. The final three are calculated at 298.15K and all energies are given in atomic units.

| a.u. | kJmol-1 | |

|---|---|---|

| Sum of electronic and zero point energies | -234.469204 | -615599 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal energies | -234.461857 | -615580 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal enthalpies | -234.460913 | -615577 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal free energies | -234.500777 | -615682 |

Calculation files: https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:Gauche_out.out https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:Anti_out.out https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:Anti_confomer_2nd.out https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:Gauche_3rd_confomer.out https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:Anti_confomer_2_ci.out https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:Anti_3rd.out https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:2nd_gauche_confomer.out https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:Anti_2_freq_out.out https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:Anti2_2nd_opt_out.out https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:Anti_2_freq_out.out

Optimising the Transition States

Chair Transition States

To begin with an allyl fragment was optimised at the HF/3-21G level. Two of these fragments were then combined to give an initial structure for the chair T.S. The two fragments were placed with the ends of the allyl fragments 2.2Å apart and then optimised using in two different ways.

The first method calculates the force constant matriix in order to find the position of the T.S. The structure was optimised and the frequency analysis in one step.

| Calculation Type | FREQ |

| Calculation Method | RHF |

| Basis Set | 3-21G |

| E(RHF)/a.u. | -231.61932246 |

| RMS Gradient Norm /a.u. | 0.00001378 |

| Imaginary Freq | 1 |

There is one imaginary frequency at -818.97 which corresponds to the formation of one bond and breaking of the other.

The second method uses a frozen co-ordinate method. The two allyl fragments were optimised with the two ends frozen at 2.2Å at the HF/3-21G level and then again with then bonds unfrozen.

| Calculation Type | FTS |

| Calculation Method | RHF |

| Basis Set | 3-21G |

| E(RHF)/a.u. | -231.61932189 |

| RMS Gradient Norm /a.u. | 0.00005807 |

The geometries of the two optimised transition states are compared in the table below

| 1st Method | 2nd Method | |

|---|---|---|

| C-C bond formed/broken | 2.02 | 2.02 |

| other C-C bonds | 1.389 | 1.389 |

They both give identical transition state geometries so either can be used depending on how much information about the transition state is known.

Calculation Data:https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:ICR_OF_CHAIR.LOG https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:ICR_CHAIR_2.LOG https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:CHAIT_TS_OTHER_OPT_PART_2.LOG https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:CHAIT_TS_OTHER_OPT.LOG https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:CHAIR_TS_GUESS_1_OPT.LOG https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:CHAIR_ICR.LOG https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:CHAIR_B3OPT.LOG https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:Chair_higher_opt_out.out

Boat Transition State

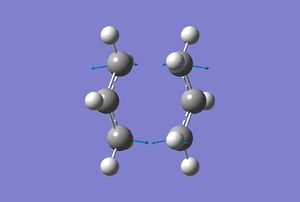

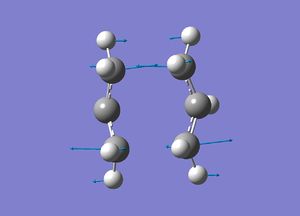

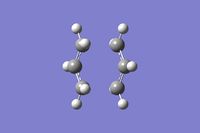

The Boat T.S was optimised using the QST2 method. This takes the reactant structure and product structure and extrapolates between the two, to find the transition state.The two structures were positioned so they are similar to a boat conformation and then optimised.

| Calculation Type | FREQ |

| Calculation Method | RHF |

| Basis Set | 3-21G |

| E(RHF)/a.u. | -231.60279992 |

| RMS Gradient Norm /a.u. | 0.00013432 |

| Imaginary Freq | 1 |

There is one imaginary frequency at -840.35 which corresponds to the formation of one bond and breaking of the other.

The bonds that are being formed are 2.14Å and the other C-C bonds are 1.382Å.

Calculation Data: https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:QST2_OPT.LOG https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:2ND_OPTIMISATION.LOG https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:2ND_OPT.LOG https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:1ST_OPT.LOG https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:Boat_higher_opt_out.out

Intrinsic reaction co-ordinate

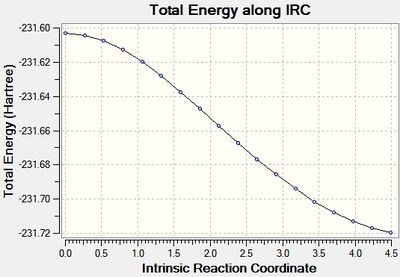

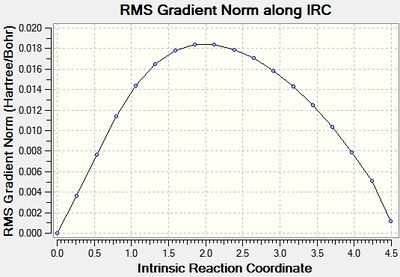

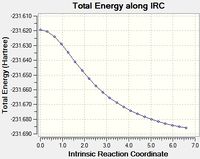

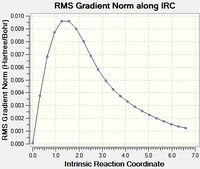

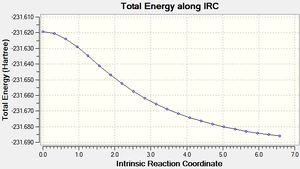

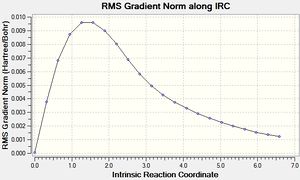

From looking at the transition states, its near on impossible to tell which conformer the reaction path will lead to. However using the IRC method the minimum energy path to the nearest minima can be followed. Because the reaction is symmetric it only needs to be run in the forward reaction.

This was initially done with 50 points along the pathway, however that didn't lead to a minima, so it was run again with 100 points.

| Points along the IRC | Energy Graph | RMS gradient Graph | Inital Structure | Final Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 |  |

|

|

|

| 100 |  |

|

|

|

As can be seen the gradient doesn't reach zero, even for 100 points, and the final structure is almost identical. In order to get further the force constants may need to be calculated at every step instead of just once.

Calculating Activation Energies

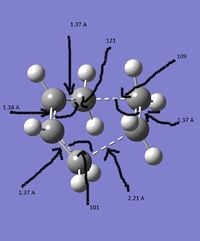

To calculate the activation energies of the reaction via each transition state the transition states need to be optimised at a higher level to give more accurate energies. Therefore both were optimised at the B3LYP/6-31G* level.

| HF/ | B3LYP/6-31G* | |

|---|---|---|

| Structure |  |

|

| Energy | -231.619322 | -234.55698 |

| new c-c bond lengths /Å | 2.02 | 1.97 |

| other bond length /Å | 1.38 | 1.41 |

| Frequency of imaginary vibration | -818.97 | -565.54 |

| HF/ | B3LYP/6-31G* | |

|---|---|---|

| Structure |  |

|

| Energy | -231.602799 | -234.54309 |

| new c-c bond lengths /Å | 2.14 | 2.21 |

| other bond length /Å | 1.38 | 1.39 |

| Frequency of imaginary vibration | -840.35 | -530.36 |

As can be seen, the geometries are relatively similar but the energies are very different. A summary of the energies is given below:

| Electronic energy | Sum of electronic and zero point energies | Sum of electronic and thermal energies | Sum of electronic and thermal enthalpies | Sum of electronic and thermal free energies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reactant | -234.611710 | -234.469204 | -234.461857 | -234.460913 | -234.500777 |

| Chair T.S | -234.556983 | -234.414929 | -234.409008 | -234.408064 | -234.443814 |

| Boat T.S | -234.543093 | -234.402342 | -234.396008 | -234.395063 | -234.431752 |

The Activation Energy of the reaction can be calculated by Eactivation = Etransition state - Ereactants

To calcultate the Activation Energy at rooom temperature 298.15 K then the sum of the electronic and thermal energies should be used. To calculate it at 0K then the sum of electronic and zero point energies should be used.

Chair Transition State @ 298.15 KEactivation = -234.409008- -234.461857 = 0.052849 au = 33.16 kcalmol-1 @ 0 KEactivation = -234.414929- -234.469204 = 0.054275 au = 34.06 kcalmol-1 Boat Transition State @ 298.15 KEactivation = -234.396008- -234.461857 = 0.065849 au = 41.32 kcalmol-1 @ 0 KEactivation = -234.402342- -234.469204 = 0.066862 au = 41.96 kcalmol-1

The reaction that goes via a Chair Transition State has a lower activion energy and is therefore the way the reaction proceeds.

The experimental values for the activation energy via a chair transition state is 33.5 kcalmol-1 and via the boat transition state 44.7 kcalmol-1. The calculated values are in very close agreement with the experimental values.

Diels-Alder Cycloaddition

The Diels Alder reaction is a [4+2] cycloaddition. The reaction was discovered in 1928 by Otto Diels and Kurt Alder.[3] The reaction can be very stereo and regio specific depending on the elctronics and sterics of the reactants used.

Two different reactions will be looked at below: 1) the reaction between Cis butadiene and Ethene. This is the simplest Diels-Alder reaction possible, there are no side groups to influence the reaction sterically or electronicly, so the basics interactions of the reaction can be clearly seen. 2) the reaction between Malic anhydride + 1,3 Cyclohexadiene. This is more complex, as both the steric effect of the briding section and the electronic effect of the functionalised dienophile must be considered.

Cis Butadiene and ethene

Cis butadiene was optimised at the HF/3-21G level.

| Calculation Type | FOPT |

| Calculation Method | RHF |

| Basis Set | 3-21G |

| E(RHF)/a.u. | -154.05394317 |

| RMS Gradient Norm /a.u. | 0.00007352 |

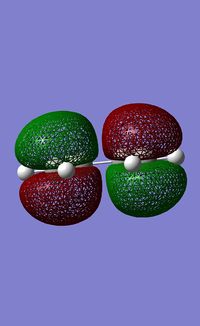

The HOMO and LUMO were then calculated using the AM1 semi-empirical MO method.

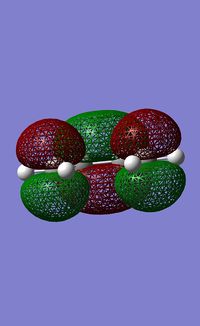

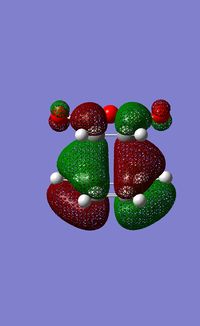

| HOMO | LUMO | |

|---|---|---|

|

| |

| Energy /a.u. | -0.35083 | 0.01977 |

| Symmetry | a | s |

The symmetry of the orbitals are determined with respect to the plane which runs through the center of the middle bond . If the orbital is symmetric with respect to reflection in the plane, then it is labeled s and if not it is labeled a.

The transition state for the reaction has an envelope-like structure. It was drawn in gaussview with the ends of the two fragments positioned 2.2Å apart. The transition structure was optimised using at the HF/3-21G level using the QST2 method.

| Calculation Type | FREQ |

| Calculation Method | RHF |

| Basis Set | 3-21G |

| E(RHF)/a.u. | -231.60320837 |

| RMS Gradient Norm /a.u. | 0.00002624 |

| Imaginary frequencies | 1 |

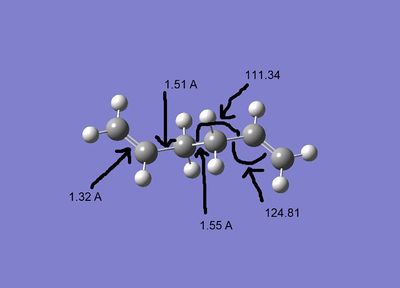

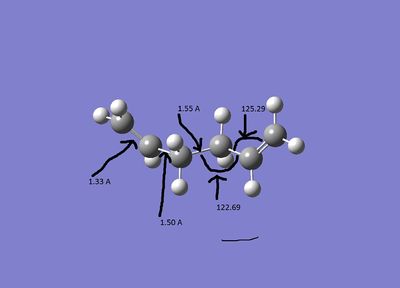

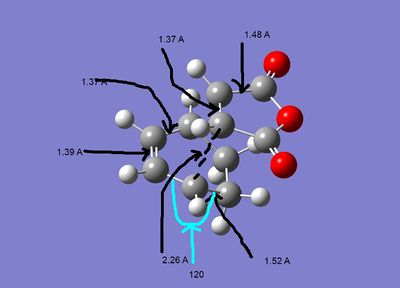

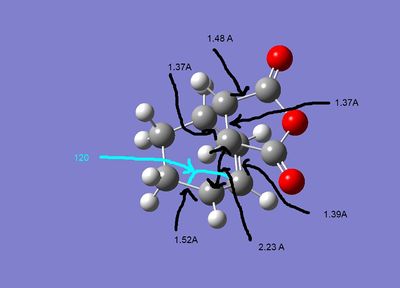

The various bond lengths and angels of the transition state are detailed above. Typical sp3 c-c bonds are ~1.54Å and sp2 c-c bonds are ~1.33Å. The Van der Waahls radius of carbon is 1.70Å[4] The σ bonds that are long compared to a σ bond, but the bonds in the cis butadiene are all approximately equal. This suggests that the starting point of the change in structure is a change in the electronic structure rather than the formation of new bonds.

The imaginary frequency occurs at -818.34 and corresponds to the formation of two new bonds in a synchronous fashion. As the new bonds form, the double bonds lengthen and the single bond in the butadiene contracts, which corresponds to the geometric changes that occur in the reaction. The lowest positive frequency occurs at 116.73 and corresponds to an asychronus movement of the two ethene carons towards the butadiene ends.

In order to ensure that the transition state had been found the IRC method was used to find the minimum energy pathway to the local minima, which should be the product. The initial structure looks like the starting material and then the final structure looks like the transition state.

The Molecular orbitals of the transition state were calculated using the AM1 semi-empirical method. The symmetry was determined with respect to the plane of symmetry detailed above.

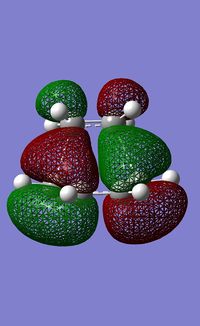

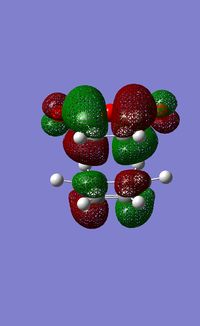

| HOMO | LUMO | |

|---|---|---|

|

| |

| Energy /a.u. | -0.32593 | 0.01842 |

| Symmetry | a | s |

The HOMO of ethene is the пc-c orbital which has s symmetry and the LUMO is the п*c-c orbital, which has a symmetry. The orbitals of ethene and butadiene can only interact if they have the same symmetry label. Therefore it can be seen that the HOMO of the transition state is made of the HOMO of butadiene and the LUMO of ethene and therefore is antisymmetric. And the LUMO of the transition state is made of the LUMO of butadiene and the HOMO of ethene and is symmetric. The reaction is allowed because the HOMO/LUMO pairs interact and are of similar sizes, so there is significant overlap.

Calculation Data: https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:QST2_TS_OPT_BUTADIENE_3.LOG https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:CIS_BUTADIENE_MO_AM1.LOG https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:CIS_BUTADIENE_INITIAL_OPTIMISATION.LOG https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:ICR_3_from_scan.out https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:MOS_OF_TRANSITION_STATE.LOG

Malic anhydride + 1,3 Cyclohexadiene

The reaction between malic anhydride + 1,3 cyclohexadiene forms mainly the endo product, the reaction is presumed to be kinetically controlled. This can be confirmed by comparing the energies of the transition states.

The reaction between malic anhydride + 1,3 cyclohexadiene forms mainly the endo product, the reaction is presumed to be kinetically controlled. This can be confirmed by comparing the energies of the transition states.

In order to find the transition states both reactants were optimised at the HF/3-12G level.

| heading | Maleic Anhydride | 1,3 Cyclohexadiene |

|---|---|---|

|

| |

| Calculation Type | FOPT | FOPT |

| Calculation Method | RHF | RHF |

| Basis Set | 3-21G | 3-21G |

| E(RHF)/a.u. | -375.10351323 | -230.54323110 |

| RMS Gradient Norm /a.u. | 0.00012414 | 0.00004255 |

The Exo and Endo transition states were optimised by calulating the hessian.

| Exo TS | Endo TS | |

|---|---|---|

|

| |

| Calculation Type | FOPT | FOPT |

| Calculation Method | RHF | RHF |

| Basis Set | 3-21G | 3-21G |

| E(RHF)/a.u. | -605.60359122 | -605.61036815 |

| RMS Gradient Norm /a.u. | 0.00001656 | 0.00003160 |

As can be seen the Exo transition state is higher in energy and so as the endo product is the one that is formed then it can be presumed that the reaction is kinetically controlled. Kinetically controlled reactions go via the lowest energy transition state regardless of whether or not it leads to the lowest energy product. It is generally considered that the stability of the endo transition state is due to steric effects destabilising the exo form and secondary orbital overlap stabilising the endo form.

The frequency analysis for both was calculated and the imaginary frequency for the exo t.s. occurs at -647.33 ant for the endo t.s it occurs at -643.57. For both the vibration correspond with the synchronous formation of two bonds between the fragments.

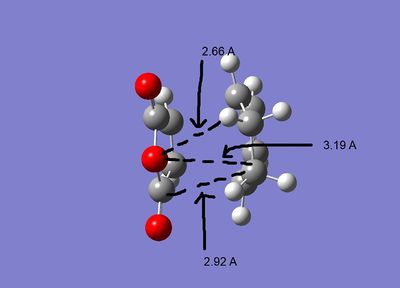

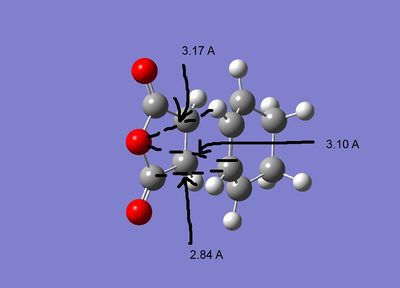

The geometries of the the two structures are given below:

| Exo | Endo |

|

|

|

|

As can be seen both of the geometries are very similar, all the bond lengths ae more or less the same, the only diffenece is the orientation of the two fragments. However in the exo form there may be more steric strain as the hydrogens for the cyclohexadiene are closer to the maleic anhydride. As can be seen in the second pictures the exo form suffers some steric strain as the hydrogens of the CH2-CH2 bringe are close to the malic anhydride. The endo form deosn't sufffer this strain as much as the bridging portion is the double bond CH-CH section, so the hydrogens are further away.

In order to explore the secondary orbtial overlap, the molecular orbitals of the system were calculated using the AM1 semi-empirical method.

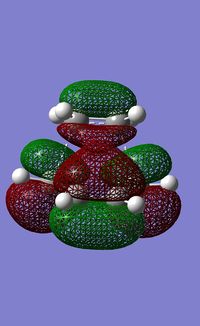

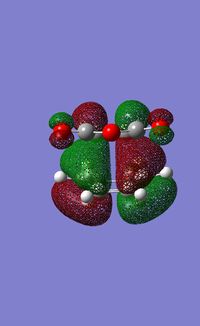

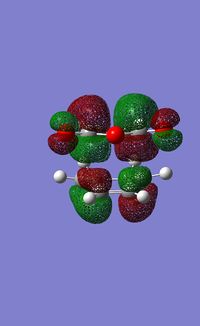

| Exo TS | Endo TS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HOMO | LUMO | HOMO | LUMO | |

|

|

|

| |

| Energy /a.u | -0.34113 | -0.04051 | -0.34321 | -0.03567 |

The HOMO of the endo TS is lower in energy than that of the exo TS. In the endo conformer the p orbitals of the oxygen are in the same region as the π systems. This means that there is an opportunity for mixing, which lowers the energy of the HOMO, stabilising the system. In the exo form the p orbitals of the oxygen are seperated from the π system, so there is no chance of them interacting.

Calculation Data:https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:DIENE_INITIAL_OPT.LOG https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:ANHYDRIDE_INITIAL_OPT.LOG https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:Exo_opt_1_out.out https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:EXO_MOS_1.LOG https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:ENDO_MOS_1.LOG

References

- ↑ A.Cope et al, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1940, 62, 441-444 DOI:10.1021/ja01859a055

- ↑ O. Wiest, A.Kersey, et. al; J. Am. Chem. Soc.; 1994, 116, 10336-10337DOI:10.1021/ja00101a078

- ↑ Diels, O. Alder, K.; Justus Liebig's Annalen der Chemie; 1928; 460; 98–122.DOI:10.1002/jlac.19284600106

- ↑ A. Bondi; J. Phys. Chem., 1964, 68 (3), pp441–451 DOI:10.1021/j100785a001