Rep:Mod:smb59mod3

Two different types of transition states are studied. Firstly the two possible transition states of the cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene and the various optimised conformers the final molecule can form are analysed and compared to literature values. The second reaction studied is the diels-alder reaction, where the formation of the transition state and the stabilising effect of secondary orbital overlap are shown to result in a reaction based of kinetics.

Cope rearrangement

1,5-hexadiene

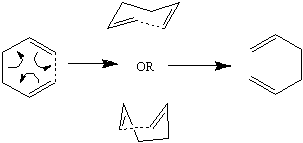

The cope rearrangement as shown involves a [3,3]-sigmatropic shift mechanism as above[1]. To study this, first the various low energy conformers of 1,5-hexadiene were identified, then using the possible transition structures (boat and chair) are analyzed and compared.

After forming a rough outline of the conformers, they were minimised by HF/3-21G first to get a good approximation, then the approximation was refined using the more accurate DFT B3LYP/3-21G, with both undergoing a frequency analysis to ensure the stationary point reached was a minimum.

| Conformer | Symmetry | HF/3-21G

Hartrees |

HF/3-21G

relative kcal/mol |

DFT B3LYP/3-21G

Hartrees |

DFT B3LYP/3-21G

relative kcal/mol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gauche1 | C2 | -231.68772[2] | 3.10 | -233.33245[3] | 2.48 |

| Gauche2 | C2 | -231.69167[4] | 0.62 | -233.33524[5] | 0.73 |

| Gauche3 | C1 | -231.69266[6] | 0.00 | -233.33636[7] | 0.03 |

| Gauche4 | C2 | -231.69153[8] | 0.71 | -233.33540[9] | 0.63 |

| Gauche5 | C1 | -231.68962[10] | 1.91 | -233.33385[11] | 1.61 |

| Gauche6 | C1 | -231.68916[12] | 2.20 | -233.33345[13] | 1.86 |

| Anti1 | C2 | -231.69260[14] | 0.04 | -233.33641[15] | 0.00 |

| Anti2 | Ci | -231.69254[16] | 0.08 | -233.33634[17] | 0.04 |

| Anti3 | C2h | -231.68907[18] | 2.25 | -233.33380[19] | 1.64 |

| Anti4 | C1 | -231.69097[20] | 1.06 | -233.33521[21] | 0.75 |

| Anti5 | C2h | -231.68540[22] | 4.56 | -233.32932[23] | 4.45 |

Using the butane analogy, where antiperiplanar is the lowest energy dihedral angle, Anti4 was formed, but due to the alkene parts of the molecule, a dihedral angle of 120' was preferred when involving them (while maintaining antiperiplanar for the central four carbons), resulting in Anti4 being the highest energy conformer.

This demonstrates that the HF optimization is a very close approximation, as the relative energies and the dihedral bond angles are all very similar to the more accurate DFT optimization, with only minor fraction of an angle changes through the different conformers, maintaining the same symmetry in all cases

As expected, the more accurate DFT B3LYP/3-21G game energies with lower values (~1.5 Hartrees), but the relative energies remained very similar. In all bar gauche2 and gauche3, the second optimisation resulted in reducing the energy difference between the comformers. Additionally, whilst the lowest energy conformer initially was gauche2, after the second optimisation the lowest was anti1, however the energy difference is so small (less than 0.1kcal/mol), that these two and anti2 can be considered essentially equally the lowest energy conformers.

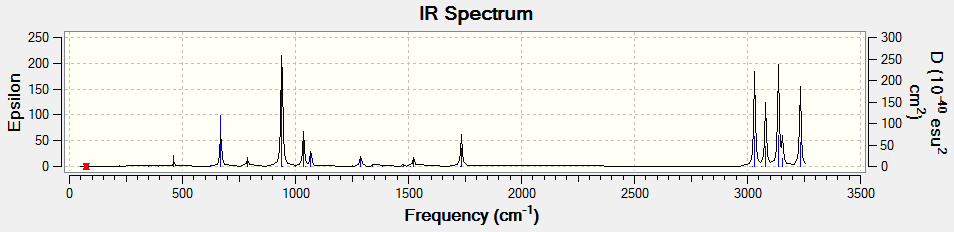

Following this, the anti2 conformer was chosen for additional analysis, undergoing DFT B3LYP/6-31G* optimisation and a frequency analysis at 298.15 and 0.0001 kelvin using Freq=ReadIsotopes.

| Stretch | Frequency | Magnitude |

|---|---|---|

| View | 670 | 20 |

| View | 940 | 61 |

| View | 1035 | 20 |

| View | 1734 | 18 |

| View | 3031 | 54 |

| View | 3080 | 36 |

| View | 3137 | 56 |

| View | 3234 | 45 |

Transition states

Boat structure

Following this, the chair and boat transition states were calculated using different methods. First, to form the chair transition state, two optimised (HF/3-21G) allyl fragments were placed (CH2CHCH2) approximating a hexane chair structure with the carbons with C2h symmetry. This was then optimised to a TS (berny), giving a single vibration at -818cm-1[24]. Afterwards, a second method was used, via freezing the bond length between the reacting carbons to 2.2 angstroms, minimising using HF/3-21G, then minimising to a TS (berny) after setting the frozen bonds to derivative, giving a transitional vibration at -818cm-1[25] again, but with 2.0199 angstroms seperating the reacting carbons (Decreasing from 2.0206).

Chair structure

To form the C2v boat structure, the transition state was found using QST2, first using ther anti2 molecule above and renumbering the atoms to simulate the molecule before and after the transition. However, this failed initially due to the shape of anti2 [26]. This was improved upon by changing the inner dihedral angle to 0 and the inside carbon angles to 100', resulting in molecules similar to just before and after a transition. This resulted in a successful transition state formed, with a transition vibration at -840cm-1[27]. An additional attempt to use the initial Anti2 molecules was successful by using QST3, which involves aiding the calculation by adding an approximated transition state. This lead to a near identical transition state at -840cm-1[28]

To demonstrate what occurs after the transition state, an IRC was performed (100 steps, force constants calculated each time, with final molecule optimised again, all using HF as above), demonstrating that the chair transition state ended forming the guache2[29][30] (view)product above after the transition step, while the boat initially formed gauche2, but subsequently minimised to form gauche3[31][32] (view)

| HF/3-21G | DFT/6-31G* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Electronic energy | Sum of electronic

and zero-point Energies |

Sum of electronic

and thermal Energies 298.15k |

Electronic energy | Sum of electronic

and zero-point Energies |

Sum of electronic

and thermal Energies 298.15k |

Sum of electronic

and thermal Energies 600k | |

| 1,5-Hexadiene | -231.69254[33] | -231.539540[34] | -231.532566[35] | -234.611710[36] | -234.469204[37] | -234.461857[38] | -234.444170[39] | |

| Chair | -231.619322[40] | -231.466696<ref[[>File:Sbmod3CL2B.LOG]]</ref> | -231.461337[41] | -234.556981[42] | -234.414906[43] | -234.408982[44] | -234.392032[45] | |

| Boat | -231.602802[46] | -231.450928[47] | -231.445299 [48] | -234.543093[49] | -234.402339[50] | -234.396005[51] | -234.378575[52] | |

| HF/3-21G | DFT/6-31G* | Expt. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Sum of electronic

and zero-point Energies |

Sum of electronic

and thermal Energies 298.15k |

Sum of electronic

and zero-point Energies |

Sum of electronic

and thermal Energies 298.15k |

Sum of electronic

and thermal Energies 600k |

0k |

| Chair | 45.71 | 44.70 | 34.07 | 33.18 | 32.72 | 33.5 ± 0.5 |

| Boat | 55.60 | 54.76 | 41.96 | 41.32 | 41.16 | 44.7 ± 2.0 |

Both sets of calculations show that the chair transition structure is ~10kcal/mol lower in energy than the boat (as expected if compared to hexane structures) transition, however the second optimisation values are significantly closer to the experimental results. This demonstrates the greater accuracy of the DFT method over the HF optimisation. The DFT versions ~1kcal/mol out compared to the range of the experimental. This shows the calculations were done correctly, and demonstrates the accuracy of the DFT method.

Diels-alder

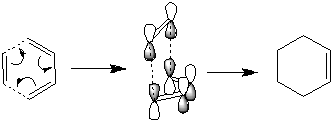

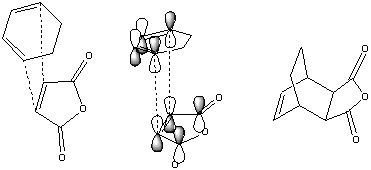

The diels-alder reaction is a cyclic addition of a alkene group to a cis conjugated diene as above. The alkene approaches and the reaction occurs due to strong orbital overlap viewable below.

To analyse this reaction, the transition state had to be predicted. This was done, as described above, by freezing the reacting bond distance at 2.2 angstroms, optimising, then optimising to a transition state with the reacting bonds set to derivative[53]. The resulting transition structure shows a distinct negative synchronous vibration at -957cm-1, confirming its nature as a transition state for the diels alder reaction. The transition state forming C-C bonds are 2.118[54] angstroms long, which collapse to 1.519[55] angstroms after a minimisation. In the \'\'\'transition state\'\'\' the butadiene segment shows bond lengths (0.138-0.140nm) similar to benzene (0.14nm) This is due to the electron donation from the butadiene HOMO into the ethene LUMO, and the ethene HOMO into the butadiene LUMO. This results in a decrease in bond order between the alkene bonds (normally 0.134nm) and an increase in the bond order for the sp2 C-C butadiene bond due to the shape of the LUMO as below.

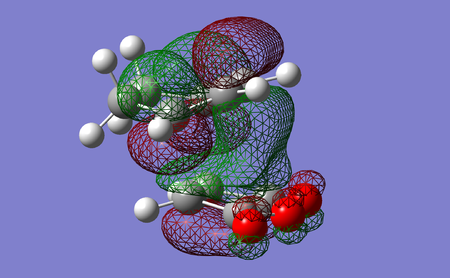

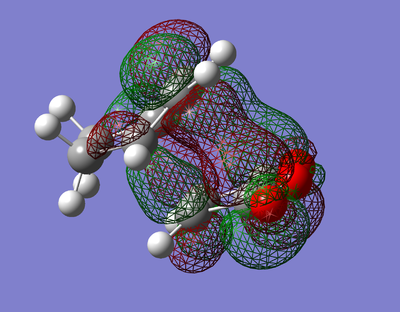

The table below shows the HOMO-LUMO orbitals of the molecules involves. They clearly show the HOMO of the transition state is the result of the ethene LUMO and the butadiene HOMO, which all share a symmetry, whilst the LUMO is formed from the thene HOMO and the butadiene LUMO, which share s symmetry.

| molecule | HOMO

(symmetry) |

LUMO

(symmetry) |

|---|---|---|

| Butadiene[56] |

|

|

| a | s | |

| Ethene[57] |

|

|

| s | a | |

| Cyclohexene TS[58] |

|

|

| a | s |

| Endo | Exo | |

|

| |

| -810cm-1 | -814cm-1 |

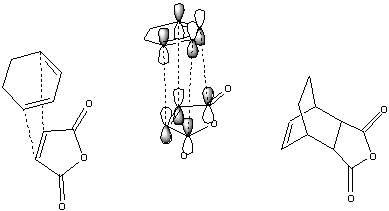

After examining the basic Diels alder reaction, the above more complex version involving stereochemistry was subsequently analysed. In this reaction, the orientation of the attack determines the subsequent transition state and final molecule. This was done in an attempt to determine which product would be the kinetic and thermodynamic product. After starting with AM1 optimised starting reactants, the transition state for each orientation was found as above using the freeze and derivative method. After acquiring the AM1 transition states, they were further refined using the PM6 optimisation method. Using these transition states, an IRC was run to find the energy of the final products.

| AM1 | PM6 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecule | Electronic energy | New C-C length | Through space

C-C length |

Electronic energy | New C-C length | Through space

C-C length |

| Endo TS[59][60] | -0.05121220 | 2.14913 | 2.85929 | -0.06243761 | 2.14913 | 2.85843 |

| Exo TS[61][62] | -0.05027834 | 2.16151 | 2.93695 | -0.05981691 | 2.16377 | 2.93486 |

| Endo[63][64] | -0.16017041 | 1.53587 | 2.98378 | -0.17125794 | 1.55749 | 2.92347 |

| Exo[65][66] | -0.15990940 | 1.53608 | 2.94318 | -0.17163675 | 1.55678 | 2.95734 |

The PM6 shows that the endo product is preferred kinetically due to the lower energy transition state, but the exo product has a lower final product and so is preferred thermodynamically. The noticable narrower endo transition state C C through space indicates secondary orbital overlap[67], viewable in LUMO2 + LUMO3 below, but absent in both the final product and both the exo transition state and final form. This stabilising interaction would explain the lower energy endo transition state and why it would be the preferred product.

| LUMO+1 | LUMO+2 | |

|

|

- ↑ Clayden, J.; Greeves, N.; Warren, S.; Wothers, P.; Organic Chemistry, 2011, Oxford University Press

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12539

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12528

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12540

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12529

- ↑ File:Sbmod3G3.LOG

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12530

- ↑ File:Sbmod3G4.LOG

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12531

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12541

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12532

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12542

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12533

- ↑ File:Sbmod3A1.LOG

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12534

- ↑ File:Sbmod3A2.LOG

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12535

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12543

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12536

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12544

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12537

- ↑ File:Sbmod3A5.LOG

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12545

- ↑ File:Sbmod3CL1.LOG

- ↑ File:Sbmod3CL2B.LOG

- ↑ File:Sbmod3CL1.LOG

- ↑ File:Sbmod3CL2.LOG

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12703

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12717

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12718

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12715

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12716

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12708

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12708

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12708

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12704

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12706

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12704

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12707

- ↑ File:Sbmod3CL2B.LOG

- ↑ File:Sbmod3CL2B.LOG

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12713

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12712

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12713

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12714

- ↑ File:Sbmod3BL2.LOG

- ↑ File:Sbmod3BL2.LOG

- ↑ File:Sbmod3BL2.LOG

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12709

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12710

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12709

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12711

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12719

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12719

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12720

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12721

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12726

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12719

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12727

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12729

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12728

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12730

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12727

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12729

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12728

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12730

- ↑ Marye Anne Fox, Raul Cardona, Nicoline J. Kiwiet J. Org. Chem., 1987, 52 (8), pp 1469–1474 DOI: 10.1021/jo00384a016 Publication Date: April 1987