Rep:Mod:smb59mod1

Samuel Bevan, CID 00600352, Year 3 computational labs - module one.

Introduction

Computational methods are a useful tool for predicting and analysing a variety of chemical systems. However, the computational requirements increase at a rapid rate for solving the wave equation as molecules get larger, assumptions are made to make the calculations quicker and more managable. While these reduce the calculations neccessary, they are not always true and so bring the chemical model away from the "true" value. Despite this, the increase in computing power available for the same price has allowed a variety of methods to become increasingly useful in modern chemistry.

Molecular mechanics

The molecular mechanics approach is based on the assumption that the total energy of a system can be found by looking at 5 distinct additive systems.

- sum of all diatomic bond lengths potential, the bond stretch given by Hooke's law

- sum of all bond angles, also from Hooke's law

- sum of all bond torsion, given by the dihedral bond angle

- van der vaal interactions, given by the Lennard-Jones potential

- sum of all electrostativ interactions from bond dipoles, from coulomb's law

This assumption works largely for simple organic molecules with relatively few substituents to get an approximate structure, but takes significantly less time to achieve than other, semi empirical methods. These values are based on the available force fields that allow these values to be calculated.

Cyclopentadiene dimer hydrogenation

Cyclopentadiene is a widely used organic molecule, largely as a precurser to the cyclopentadienyl ligand 'Cp', which has useful properties used in the catalyst industry. While it can be stored for several days at -20'C, at higher temperatures (but below 150'C)* it dimerises via a Diels-Alder reaction to dicyclopenadiene. Diels-Alder reactions generally follow the endo rule, and it can be seen experimentally that the dimer is predominantly of the endo form, thus the following molecular mechanic approach determines if this is due to thermodynamic or steric effects.

As can be seen from the table below, the endo form has a higher energy (~2.1kcal/mol). As it is the dominant product, this suggests the following reaction pathways:

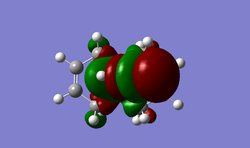

A closer look of the data shows that most of the contribution to the energy difference comes from the torsion energy contribution (1.9kcal/mol). This increase in torsion can be attributed to the close proximity of the double bonds (~3.1Å) compared to the exo form (~4.2Å) causing strain due to their repulsion. The transition states increased stability is likely due to the interaction between the 4π LUMO and the 2π HOMO as below

Now that the Diels-Alder products have been compared, the two products formed when the discussed endo molecule is hydrogenated are discussed. Analysing the endo product 2's double bond angles, it can be seen that the bond hydrogenated in 3 has an angle of ~113' (compared to optimal of 122) while the bond hydrogenated in 4 has an angle of ~108', which would be expected to have the most bend strain. As the optimal dihedral angle of carbon single bonds is ~109', the reduction to molecule 4 would be expected to relieve more strain and be thermodynamically favoured.

The table below reveals the expected result, that the product 4 has a significantly lower energy (~7.6 kcal/mol), from which the main contribution is the difference in bond strain (5.8kcal/mol). This suggests that, unless the hydrogenation results in favouring a kinetic product, product four is the more favoured for a single alkene group hydrogenation on molecule 2.

| Diels alder product | Hydrogenation product | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecule number | 1 (exo) | 2 (endo) | 3 | 4 |

| Stretch | 1.2847 | 1.2510 | 1.2383 | 1.1307 |

| Bend | 20.5796 | 20.8497 | 18.7825 | 13.0165 |

| Stretch-bend | -0.8378 | -0.8358 | -0.7517 | -0.5651 |

| Torsion | 7.6568 | 9.5107 | 12.7137 | 12.4126 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.14184 | -1.5445 | -1.3346 | -1.3272 |

| 1,4 VDW | 4.2340 | 4.3188 | 6.0490 | 4.4389 |

| Dipole/dipole | 0.3775 | 0.4476 | 0.1632 | 0.1410 |

| Total | 31.8765 | 33.9975 | 36.8603 | 29.2475 |

conformation/atropisomerism of a large ring ketone

In the production of taxol (involved in anti-cancer treatments), an atropisomer is produced. an atropisomer is a molecule which contains single bonds that, due to torsional strain (ie caused by bulky bonded groups), are generally prevented from rotation. This can result in multiple stable structures which are isolatable from each other, but may interconvert at higher temperatures.

As can be seen from the following tables, there are a number of possible forms this intermediate can take. However, just looking at the two most stable isomers, both with the chair conformer, it is clear than molecule 10 is of lower energy (~5.1kcal/mol). Most of this increased stability comes from angle strain (~5.2kcal/mol), but it also has increased torsional strain (~1.4 kcal/mol). The main source of angle strain in isomer 9 would be caused by the repulsion between the oxygen and the adjacent bridgehead and its methyl group, which is significantly further away in isomer 10. To confirm the measurement, an additional force field (MMFF94) was used, resulting in a 9 chair energy of 70.5426kcal/mol and 10 chair energy of 60.5632, confirming that isomer 10 is the more stable.

| Molecule number | 9 chair | 9 twist | 10 chair | 10 twist a | 10 twist b | 10 twist c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 2.7850 | 2.8797 | 2.6201 | 2.7104 | 2.8327 | 2.7071 |

| Bend | 16.5397 | 17.2783 | 11.3334 | 11.7413 | 12.9748 | 11.8299 |

| Stretch-bend | 0.4343 | 0.4729 | 0.3429 | 0.3236 | 0.3898 | 0.3920 |

| Torsion | 18.2439 | 20.6100 | 19.6800 | 21.8664 | 22.9884 | 22.8842 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.5429 | -0.8896 | -2.1637 | -2.0959 | -1.7609 | -1.9953 |

| 1,4 VDW | 13.1074 | 14.3682 | 12.8724 | 13.9193 | 14.1205 | 14.3370 |

| Dipole/dipole | -1.7245 | -1.7092 | -2.0022 | -2.0315 | -2.0321 | -1.9970 |

| Total | 47.8397 | 53.0103 | 42.6829 | 46.4335 | 49.5132 | 48.1579 |

As can be seen, their is considerable bond strain in the hydrogenated form of 10 hydrogenated as the bond angle is 119.3' (optimal ~109') in comparison to C=C 10 which has a bond angle of 123.1 (optimal 122). This contribution (known as olefin strain) [1] [2] result in the alkene group being considerably mor resistant to hydrogenation, explaining the slow rate of reaction.

semi empirical and DFT molecular theory

While these methods tend to get approximations closer to "true" values, they also require considerably more processing to do so, hence why many of them were done on an available SCAN system.

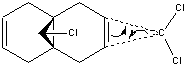

regioselectivity of electrophilic carbenylation of a chloro substituted bicyclic diene

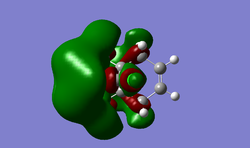

SOPAC orbitals were calculated, however they were very unsymmetrical and so only the refined guassian orbitals have been included. As can be seen from the table below, most of the electron density in the HOMO orbital is centered around the alkene group endo to the chlorine. This indicates that it would be the most nucleophilic alkene. If the molecule is compared to a similar molecule with hydrogen replacing the chlorine, the dihedral angle for the alkene groups is 18.8', however for molecule 12 the two angles are 19.7' and -1.4'. This shows the chlorines effect on the sys alkene, as it is twisting the molecule to push the close by electron dense group away. This repulsion results in pushing it away from the bridgehead (and slightly squashing the two carbons together) causing it to be higher in energy that the exo alkene, making it more nucleophilic to attack. Another observation from the moleculer structure (most evident in the LUMO + 2) is the empty C-Cl antibonding orbital that is pointing directly at the exo alkene. This very close, empty, relatively low energy (due to chlorines electronegativity) orbitals proximity could reduce the electron density of the exo alkene, making it less nucleophillic. Together this suggests the endo alkene is much more likely to be a target for electrophilic attack

| Molecule Orbital | HOMO -1 | HOMO | LUMO | LUMO +1 | LUMO +2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gauss |

|

|

|

|

|

| Molecule Orbital | HOMO -1 | HOMO | LUMO | LUMO +1 | LUMO +2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gauss |

|

|

|

|

|

The table below shows the stretching frequencies. There is a clear increase in the energy of the C-Cl stretch due to the absence of the alkene group previously donating to its antibonding orbital, resulting in a higher bond order and thus strength. The main difference for the alkene stretches is within the dialkene (with the monoalkene having a very similar stretch energy to its dialkene counterpart), with the endo alkene having a higher energy stretch. As mentioned above, the donation into the C-Cl antibonding orbital would reduce the bond order of both the C-Cl and the C=C bond involved.

| Molecule | C-Cl | C=C | C=C |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12 |

772.622cm-1 |

1760.95cm-1 |

1740.72cm-1 |

| Hydrated 12 |

782.24cm-1 |

1757.32cm-1 |

NA |

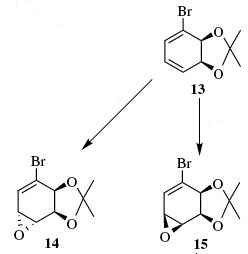

neighbouring group participation

In this section, the position of a neighbouring C=O bond effects on the nucleophilic attack on a pyranose rings and the resulting stereochemistry is predicted using both MM2 and MOPAC methods. As a general rule, bulkier groups tend to be favoured in axial positions in pyranose rings due to the decreased steric effects, however, the anomeric effect causes heteroatom substituents bonded to the oxygens adjacent carbon to favour the axial positions, thought to be caused by donationfrom the ring oxygens lone pair and the empty C-O antibonding orbital. To investigate whether this stereochemistry is held with the neighbouring group participation, Two isomers were studied, A and B , with the predicted intermediate structures analysed as well.

The final structure after nucleophilic attack would most effected if the neighbouring group sterically hinders attack from below the ring, resulting in attack from above becoming much more likely, and thus the dominant product formed. This would occur for intermediates The MOPAC results gave the expected results, showing that

| Molecule | A | A\' | B | B\' | C | C\' | D | D\' |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 2.2487 | 2.1860 | 2.3393 | 2.5857 | 1.9448 | 2.5857 | 1.9446 | 2.5862 |

| Bend | 13.3083 | 13.4509 | 13.1572 | 16.7420 | 13.5647 | 19.6847 | 13.6059 | 16.7418 |

| Stretch-bend | 1.0368 | 1.0141 | 0.9779 | 0.7247 | 0.7556 | 0.7024 | 0.7060 | 0.7247 |

| Torsion | 0.3860 | 1.4640 | -0.2146 | 6.9864 | 8.6190 | 5.2876 | 6.8320 | 6.9864 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.2822 | -1.5911 | -1.5616 | -2.6598 | -3.5116 | -3.3347 | -3.6631 | -2.6598 |

| 1,4 VDW | 17.4000 | 17.8319 | 18.2740 | 19.3638 | 18.0269 | 18.4563 | 18.1286 | 19.3634 |

| Charge/Dipole | -7.2621 | -3.9127 | -11.1467 | -1.9885 | -0.3779 | 3.0644 | 1.7082 | -1.9884 |

| Dipole/dipole | 6.4368 | 5.2840 | 5.4413 | -0.8813 | 1.3718 | 0.1202 | -0.4708 | -0.8814 |

| Total | 32.2724 | 35.7271 | 27.2668 | 40.8730 | 37.6496 | 46.5667 | 38.7913 | 40.8730 |

| PM6 | -84.50687 | -69.17556 | -88.51889 | -76.46981 | -89.82077 | -66.63917 | -84.07828 | -66.72516 |

As can be seen from the data above, molecule A adopts a conformer that increases the rate of the beta product forming, while molecule B does the reverse. The stabilisation is substantial, as 1kcal/mol is 4.184kcal/mol, would make the neighbouring group participation effect quite substantial

mini project

In many reactions, it is necessary to identify the formed product to ensure the reaction proceeded as expected. In this section a molecules predicted spectral data is compared to the recorded data show how it is possible to show that a stereospecific reaction occured. During a recent paper [5] demonstrating the formation of enantiopure α-substituted cyclohexanones, one of the intermediates determining the final stereochemistry can be identified by its spectral data, particularly its optical rotation. The IR and C13 data was unavailable for both compounds, so it is not possible to compare the data. The table below shows a comparison of the predicted and recorded H NMR for the two possible isomers produced.:

| Molecule | isomer 1 | isomer 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| spectra | predicted[6] | actual[7] | predicted[8] | actual[9] |

| 3H | 1,4 | 1.4 | 1.46 | 1.44 |

| 3H | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.48 | 1.47 |

| 1H | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.35 | 3.34 |

| 1H | 3.7 | 3.6 | 3.60 | 3.60 |

| 1H | 4.9 | 4.5 | 4.36 | 4.42 |

| 1H | 4.9 | 4.7 | 4.97 | 4.89 |

| 1H | 6.7 | 6.7 | 6.67 | 6.49 |

As you can see, the values for the hydrogen shifts are too similar to accurately identify the formed product. the optical rotation however gives significantly better differences:

| Molecule | isomer 1 | isomer 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| predicted[10] | actual[11] | predicted[12] | actual[13] | |

| [α] | -114.6' | -67.4' | 125.6' | 55.0' |

This shows a very clear method of identifying the two isomers. The substantial difference in values could be caused by a variety of effects. The different solvents used (methanol and chloroform)only contributed a difference of ~1'[14]. The magnitude of both products acquired data being less than predicted could be due to the combination of impurity (either of the other isomer, reactant or other) and the non-perfect nature of the gaussian calculation. However, the significant difference between the two products makes this a particularly good test for identifying between the products.

- ↑ Alan B. McEwen, Paul v. R. Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1986, 108 (14), pp 3951–3960 DOI:10.1021/ja00274a016

- ↑ Philip M. Warner, Chem. Rev., 1989, 89 (5), pp 1067–1093, DOI: 10.1021/cr00095a007

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11883

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11882

- ↑ Germán Fonseca, Gustavo A. Seoane,"Chemoenzymatic synthesis of enantiopure α-substituted cyclohexanones from aromatic compounds", Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, Volume 16, Issue 7, 4 April 2005, Pages 1393–1402

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11880

- ↑ Nguyen, Ba V.; York, Chentao; Hudlicky, Tomas, Tetrahedron, 1997 , vol. 53, # 28 p. 8807 - 8814

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11881

- ↑ PROGEN INDUSTRIES LIMITED; THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY, Patent: WO2006/135973 A1, 2006 ;

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11878

- ↑ Nguyen, Ba V.; York, Chentao; Hudlicky, Tomas, Tetrahedron, 1997 , vol. 53, # 28 p. 8807 - 8814

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11877

- ↑ Hudlicky, Tomas; Rulin, Fan; Tsunoda, Toshiya; Luna, Hector; Andersen, Catherine; Price, John D., Israel Journal of Chemistry, 1991 , vol. 31, # 3 p. 229 - 238

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11879