Rep:Mod:slockett

Protocol followed given here

In this experiment, the regioselectivity and geometry of the hydrogenation of a cyclopentadiene dimer and the conformation of an intermediate in the synthesis of the drug Taxol (referred to as 9 and 10 in this discussion, equivalent to intermedaites 5 and 6 (X & Y = H) in Elmore and Paquette's paper [1]) are predicted using molecular mechanics in the program Avogadro. The 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra are then calculated for intermediates further along the total synthesis of Taxol (referred to in this discussion and in the literature[2] as 17 and 18) to compare with the literature's experimental values. Interesting structural features of precursors for the asymmetric epoxidation Jacobsen and Shi catalysts are investigated using the program Mercury and discussed. The NMR spectra and optical rotation of the epoxides formed by one of these asymmetric catalysts are then also calculated and compared with the literature - from alkenes β-methylstyrene [3][4] and 1,2-dihydronaphthalene[5][6]. From these calculations, with reference to the literature, the absolute conformation of these epoxides is determined.

Computation Laboratories, Organic Computational (1C)

Conformational analysis using molecular mechanics

The hydrogenation of the favoured cyclopentadiene dimer

As described in the protocol, the endo dimer is favoured over the exo dimer when cyclopentadiene dimerises (figure 1). However, when the geometries of the exo and endo products (figure 2) were optimised using molecular mechanics, using the MM1 forcefield MMFF94s and a conjugate gradient algorithm, the exo product was found to be lower in energy than the endo product (table 1). This would therefore suggest that the reaction is under kinetic instead of thermodynamic control as the higher energy conformer is formed in preference to the lower energy one.

When the endo dimer is hydrogenated, there are two possible double bonds where the reaction can take place. The relative stabilities of the two possible hydrogenated dimers (figure 3) were investigated; the hydrogenated dimer 2 (dimer 2) was found to be lower in energy overall than hydrogenated dimer 1 (dimer 1) (table 1). The stretching, bending, torsional and Van der Waals energies of dimer 2 were all found to be lower than those of dimer 1; however dimer 1's electrostatic energy was found to be slightly lower than that of dimer 2. We can say overall that thermodynamically, the double bond left alone in dimer 1 would seem to be the easier double bond to hydrogenate.

Table 1. Energies of the exo and endo dimers and the two hydrogenated endo dimers

| Exo Dimer | Endo Dimer | Hydrogenated Dimer 1 | Hydrogenated Dimer 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Structure |

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||

| Total Energy | kJ/mol | 231.838 | 243.633 | 212.366 | 172.737 | ||||||||||||

| kcal/mol | 55.37344 | 58.19067 | 50.72285 | 41.25749 | |||||||||||||

| Bond stretching energy | kcal/mol | 3.54289 | 3.46798 | 3.30967 | 2.82307 | ||||||||||||

| Angle bending energy | kcal/mol | 30.77265 | 33.1886 | 30.86799 | 24.68541 | ||||||||||||

| Stretch bending energy | kcal/mol | -2.04137 | -2.08222 | -1.92696 | -1.65717 | ||||||||||||

| Torsional energy | kcal/mol | -2.73017 | -2.94984 | 0.04849 | -0.37829 | ||||||||||||

| Out-of-plane bending energy | kcal/mol | 0.01486 | 0.02184 | 0.0152 | 0.00028 | ||||||||||||

| Van der Waals energy | kcal/mol | 12.80092 | 12.35924 | 13.28738 | 10.63717 | ||||||||||||

| Electrostatic energy | kcal/mol | 13.01366 | 14.18506 | 5.12098 | 5.14702 | ||||||||||||

Intermediate 9 or 10 (figure 4) is an intermediate compound in the total synthesis of the anti-cancer drug Taxol, as first synthesised by Paquette[2]. We use molecular mechanics here to determine which of these structures is the most stable, as before using the MMFF94s force field and conjugate gradient algorithm. As there is a hexane ring present in the structure, there are 4 possible conformers of both of these intermediates, which are shown below in tables 2 and 3 for intermediates 9 and 10 respectively. These both show two structures which have a "boat" hexane ring and two with a "chair" hexane ring.

The lowest energy conformer of intermediate 9 is chair 1 as shown below, a molecule of energy 295.389 kJ/mol. The lowest energy isomer of intermediate 10 however is even lower than this; chair 1 has an energy of 253.557 kJ/mol. The chair 1 conformer of intermediate 10 is therefore the most stable isomer.

Table 2. The energies of the possible conformers of intermediate 9

| Boat | Twist Boat | Chair 1 | Chair 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Structure |

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||

| Total energy | kJ/mol | 375.965 | 319.396 | 295.389 | 358.172 | ||||||||||||

| kcal/mol | 89.79765 | 76.28634 | 70.55244 | 34.38261 | |||||||||||||

| Bond stretching energy | kcal/mol | 8.88651 | 7.9413 | 7.71872 | 7.94585 | ||||||||||||

| Angle bending energy | kcal/mol | 34.67959 | 29.50317 | 28.31913 | 37.52753 | ||||||||||||

| Stretch bending energy | kcal/mol | 0.17852 | 0.07969 | -0.05154 | 0.12799 | ||||||||||||

| Torsional energy | kcal/mol | 5.81378 | -0.37829 | 0.0814 | 3.9458 | ||||||||||||

| Out-of-plane bending energy | kcal/mol | 1.87177 | 0.95266 | 0.97655 | 1.45543 | ||||||||||||

| Van der Waals energy | kcal/mol | 38.20312 | 34.71224 | 33.21088 | 34.38261 | ||||||||||||

| Electrostatic energy | kcal/mol | 0.16435 | 0.31766 | 0.2973 | 0.1628 | ||||||||||||

Table 3. The energies of the possible conformers of intermediate 10

| Boat | Twist Boat | Chair 1 | Chair 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Structure |

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||

| Total energy | kJ/mol | 277.682 | 342.519 | 253.557 | 315.096 | ||||||||||||

| kcal/mol | 66.32316 | 81.80931 | 60.56109 | 75.25949 | |||||||||||||

| Bond stretching energy | kcal/mol | 7.73618 | 8.99275 | 7.60364 | 8.27223 | ||||||||||||

| Angle bending energy | kcal/mol | 19.57685 | 23.69749 | 18.83788 | 21.08502 | ||||||||||||

| Stretch bending energy | kcal/mol | -0.05755 | -0.10479 | -0.13897 | -0.22445 | ||||||||||||

| Torsional energy | kcal/mol | 3.17772 | 9.47371 | 0.1606 | 8.75392 | ||||||||||||

| Out-of-plane bending energy | kcal/mol | 0.84867 | 1.68344 | 0.85386 | 1.56244 | ||||||||||||

| Van der Waals energy | kcal/mol | 35.08658 | 37.5723 | 33.30396 | 35.35747 | ||||||||||||

| Electrostatic energy | kcal/mol | -0.0453 | 0.49441 | -0.05988 | 0.45287 | ||||||||||||

Spectroscopic simulation using quantum mechanics

Intermediates 17 and 18 (figure 5) are intermediates further along the total synthesis of Taxol[2] from intermediates 7 and 8 detailed above. Based on the calculations above showing chair 1 of intermediate 10 to be the lowest energy isomer, we assume that a structure built on this framework for intermediate 18 will be the lowest energy isomer from all of the intermediate 17 and 18 conformers. The structure for intermediate 18 was altered from intermediate 10 and optimised in Avogadro, again using the MMFF94s force field and conjugate gradient algorithm, energies for which can be found in table 4.

To confirm our assertion that intermediate 18 would be lower in energy than intermediate 17 based on previous calculations, the same procedure was followed for intermediate 17, using the chair 1 (lowest energy) conformer of intermediate 9 as the skeleton. Intermediate 17 was found to indeed be higher in energy and its details can be found alongside those of intermediate 18 in table 4 below.

Table 4. 3D optimised structure of intermediates 17 and 18 and calculated energies

| Intermediate 18 | Intermediate 17 | |||||||

| Structure |

|

| ||||||

| Total energy (kJ/mol) | 420.543 | 436.871 | ||||||

| Total energy (kcal/mol) | 100.44492 | 104.34479 | ||||||

| Total bond stretching energy (kcal/mol) | 15.05368 | 15.63139 | ||||||

| Total angle bending energy (kcal/mol) | 30.89916 | 32.26978 | ||||||

| Total stretch bending energy (kcal/mol) | 0.60979 | 0.01258 | ||||||

| Total torsional energy (kcal/mol) | 9.72008 | 11.49513 | ||||||

| Total out-of-plane bending energy (kcal/mol) | 0.91682 | 1.26057 | ||||||

| Total Van der Waals energy (kcal/mol) | 49.32789 | 51.32910 | ||||||

| Total electrostatic energy (kcal/mol) | -6.08251 | -7.65376 |

A gaussian input file was then created for the HPC to calculate the NMR spectra of intermediate 18 to compare to the literature.

The 1H and 13C NMR spectra generated in this calculation are shown below in figures 6 and 7. These spectra were calculated for our compound in deuterated benzene and are referenced relative to TMS.

Table 5 below shows the values from figures 6 and 7 above against the experimental values given by Paquette et al[2]. The 13C NMR values are easily compared to the literature values as all of the carbons are in different environments (hence no integrals shown in the second part of the table); the differences in shift value are also quite small, showing how the theory correlates well with experiment. The 1H NMR shifts are more difficult to compare as the degeneracy and grouping in the literature does not correlate well with our calculations. The figures have been arranged in the table to ease comparison, but they are not a perfect match.

Table 5. Literature 1H NMR and 13C NMR values compared to calculated NMR values for intermediate 18

| 1H NMR | 13C NMR | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literature | Calculated | Differences | Literature | Calculated | Shift differences/ppm | |||

| Shift/ppm | Integral | Shift/ppm | Integral | Shift differences/ppm | Integral differences | Shift/ppm | Shift/ppm | |

| 5.21 | 1 | 5.955059219 | 1 | 0.745059 | 0 | 211.49 | 218.259919 | 6.77 |

| 3.00-2.70 | 6 | 3.1139847 | 2 | 0.1139847 | +2 | 148.72 | 148.2557636 | 0.46 |

| 2.972106896 | 1 | within range | 120.9 | 120.387525 | 0.51 | |||

| 2.861090758 | 4 | within range | 74.61 | 84.20736419 | 9.60 | |||

| 2.751951225 | 1 | within range | 60.53 | 62.79151069 | 2.26 | |||

| 2.70-2.35 | 4 | 2.545696022 | 1 | within range | 0 | 51.3 | 54.82637605 | 3.53 |

| 2.480872634 | 1 | within range | 50.94 | 53.82818315 | 2.89 | |||

| 2.351107258 | 2 | within range | 45.53 | 49.4049835 | 3.87 | |||

| 2.20-1.70 | 6 | 2.029390863 | 3 | within range | +1 | 43.28 | 47.98113034 | 4.70 |

| 1.87185479 | 1 | within range | 40.82 | 42.61475496 | 1.79 | |||

| 1.820755057 | 1 | within range | 38.73 | 42.29678615 | 3.57 | |||

| 1.706875599 | 2 | within range | 36.78 | 41.83321839 | 5.05 | |||

| 1.58 | 1 | no match | 35.47 | 39.35044181 | 3.88 | |||

| 1.50-1.20 | 3 | 1.486925372 | 2 | within range | -1 | 30.84 | 34.81514683 | 3.98 |

| 1.1 | 3 | 1.342237281 | 2 | 0.242237281 | -1 | 30 | 31.25308974 | 1.25 |

| 1.07 | 3 | 1.233011059 | 2 | 0.163011059 | -1 | 25.56 | 26.86545792 | 1.31 |

| 1.03 | 3 | 1.018811899 | 2 | within range | 0 | 25.35 | 26.32721098 | 0.98 |

| 0.90741824 | 1 | 22.21 | 25.17237531 | 2.96 | ||||

| 0.711328454 | 1 | 21.39 | 23 | 1.68 | ||||

| 19.83 | 22.89378644 | 3.06 | ||||||

The log file output from the HPC gave us the following energies for intermediate 18

- Zero-point-energy correction = 0.466062 a.u.

- Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies (free energy) = -1651.372069 a.u.

These energies were also calculated for intermediate 17, and are shown to be very similar to those of intermediate 18.

- Zero-point-energy correction= 0.466012 a.u.

- Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies (free energy) = -1651.367311 a.u.

For reference, the NMR spectra for intermediate 17 were also generated for the compound in benzene, again referenced to TMS:

Analysis of the properties of the synthesised alkene epoxides

The two epoxidations that will be studied will be those of beta-methylstyrene and 1,2-dihydronaphthalene, both shown in figure 10. The two asymmetric catalysts chosen for these epoxidations are the Shi and Jacobsen catalysts. The synthesis of the Shi catalyst is shown in figure 11, the synthesis of the Jacobsen catalyst in figure 12. We will primarily look at the stable precursors as they have been studied extensively. The active catalysts are unstable and are therefore significantly harder to analyse in practice.

Crystal structure of the Shi and Jacobsen catalysts

Shi catalyst precursor - C-O bond lengths at anomeric centres

The structure of the Shi catalyst precursor was found in the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) to be structure of serial number NELQEA. This structure was analysed in the program Mercury to find the C-O bond lengths on anomeric centres; these bond lengths are shown in figure 12. The bond lengths are not the same on each of the structures shown in the database. This is no doubt due to differences in crystal packing forces in different parts of the crystal structure, and is important to note therefore that the molecules in the bulk crystal are not all completely identical. The first terms (in green) in figure 12 are from one of the structures, the second (in pink) are from the other.

Jacobsen catalyst precursor - tBu approach distances

The structure of the Jacobsen catalyst precursor was found in the CCDC to be the structure of serial number TOVNIB. This structure was analysed in the program Mercury to find the approach distances of the tBu distances around the structure. Both the intermolecular and intramolecular distances are shown in figure 13, right. Again the intramolecular distances are different on the two molecules shown, most likely due to differences in crystal packing forces.

Predicting NMR of epoxides

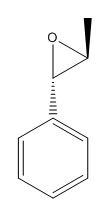

Epoxidation of β-methylstyrene

The epoxidated β-methylstyrene, β-methylstyrene oxide (figure 14), was analysed according to the same protocol at intermediates 17 and 18. Its structure was first draw out and optimised in Avogadro using the MMFF94s force field and conjugate gradient algorithm before creating a Gaussian file to run on the HPC to predict the 1H and 13C NMR spectra (figures 15 and 16 respectively). These values are then compared to those in the paper by Vyas et al[3] in table 6.

Pentahelicene |

Figure 14. 3D structure of β-methylstyrene oxide

Table 6. Calculated and literature[3] 1H and 13C NMR data

| 1H NMR | 13C NMR | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literature | Calculated | Shift differences/ppm | Literature | Calculated | Shift differences/ppm | ||

| Shift/ppm | Integral | Shift/ppm | Integral | Shift/ppm | Shift (ppm) | ||

| 7.15-7.34 | 5 | 7.506899366 | 3 | 0.166899 | 137.9 | 135.8989718 | 2.001028216 |

| 7.399807488 | 2 | 0.059807 | 128.5 | 123.9321749 | 4.567825104 | ||

| 3.52 | 1 | 3.54938925 | 1 | 0.02938925 | 128.1 | 123.2129232 | 4.887076826 |

| 2.98 | 1 | 2.72078549 | 1 | 0.25921451 | 125.7 | 122.8612505 | 2.838749477 |

| 1.4 | 3 | 1.631956342 | 2 | 0.231956342 | 122.3673573 | 3.332642713 | |

| 0.701598981 | 1 | 0.698401019 | 121.9445469 | 3.755453103 | |||

| 59.6 | 58.18131201 | 1.418687995 | |||||

| 59.1 | 55.28408884 | 3.815911158 | |||||

| 18 | 18.61664888 | 0.616648882 | |||||

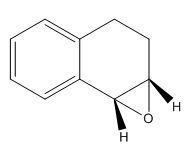

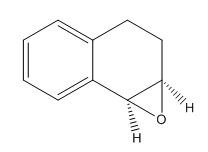

Epoxidation of 1,2-dihydronaphthalene

The epoxidated 1,2-dihydronaphthalene (figure 17), was analysed according to the same protocol at intermediates 17 and 18. Its structure was first draw out and optimised in Avogadro using the MMFF94s force field and conjugate gradient algorithm before creating a Gaussian file to run on the HPC to predict the 1H and 13C NMR spectra (figures 18 and 19 respectively). These values are then compared to those in the paper by Dai et al[5] in table 7.

Pentahelicene |

Figure 17: 3D structure of epoxidated 1,2-dihydronaphthalene

Table 7. Literature[5] and calculated 1H and 13C NMR values for epoxidated 1,2-dihydronaphthalene

| H NMR | C NMR | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literature | Calculated | Shift difference/ppm | Literature | Calculated | Shift difference/ppm | ||

| Shift | Intergral | Shift/ppm | Integral | Shift | Shift/ppm | ||

| 7.39 | 1 | 7.492071325 | 1 | 0.102071325 | 137.26 | 134.452517 | 2.807483032 |

| 7.28-7.18 | 2 | 7.363497679 | 2 | 0.083497679 | 130.11 | 131.918175 | 1.808175035 |

| 7.08 | 1 | 7.289148112 | 1 | 0.209148112 | 128.99 | 126.2982328 | 2.691767191 |

| 3.84 | 1 | 3.450699101 | 1 | 0.389300899 | 126.69 | 123.6140667 | 3.075933285 |

| 3.73 | 1 | 3.232344214 | 1 | 0.497655786 | 123.4138918 | 3.27610816 | |

| 2.89-2.71 | 1 | 2.816372931 | 1 | within range | 120.7569045 | 5.933095462 | |

| 2.54 | 1 | 2.347636141 | 1 | 0.192363859 | 55.68 | 53.77089091 | 1.909109089 |

| 2.41 | 1 | 2.228022346 | 1 | 0.181977654 | 53.34 | 51.74800972 | 1.591990284 |

| 1.76 | 1 | 1.60757252 | 1 | 0.15242748 | 24.96 | 28.58458754 | 3.62458754 |

| 22.39 | 24.54054215 | 2.150542151 | |||||

Optical rotation of epoxides

The optical rotations for the epoxides of alkenes β-methylstyrene and 1,2-dihydronaphthalene were calculated using a Guassian input file in the HPC (from structures optimised in the sections above, figures 14 and 17). The calculated values along with literature values[4][6] are shown in table 8 below. The reliability of these values as a means of making any definite statements is dubious, due to the vast ranges in value across the literature. For example, the given value in table 8 is 125 degrees for β-methylstyrene oxide from Rosenberger et al[4], however Wang et al[7] give a value of 40.8 degrees; no negligible difference of ~80 degrees.

Table 8. Optical rotation values for both epoxides, literature and calculated with structures

| β-methylstyrene epoxide | 1,2-dihydronaphthalene | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literature[4] | Calculated | Literature[6] | Calculated | |

| Optical rotation/degrees | 125 | -102.27 | 133 | -183.02 |

| Structure |  |

|

|

|

References

- ↑ S. W. Elmore and L. A. Paquette,Tetrahedron Letters, 1991, 32(3), 319-322; DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 L. A. Paquette, N. A. Pegg, D. Toops, G. D. Maynard and R. D. Rogers,J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1990, 112, 277-283; DOI:10.1021/ja00157a043

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 D. J. Vyas, E. Larionov, C. Besnard, L. Guénée and C. Mazet, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2013, 135(16), 6177-6183; DOI:10.1021/ja400325w

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 M. Rosenberger, W. Jackson and G. Saucy,Helvetica Chimica Acta, 1980, 63(6), 1665-1674; DOI:10.1002/hlca.19800630636

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 W. Dai, J. Li, G. Li, H. Yang, L. Wang and S. Gao,Org. Lett., 2013, 15(16), 4138-4141; DOI:10.1021/ol401812h

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 D. R. Boyd, N. D. Sharma, R. Agarwal, N. A. Kerley, R. A. S. McMordie, A. Smith, H. Dalton, A. J. Blacker and G. N. Sheldrake,J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun., 1994, 14, 1693-1694; DOI:10.1039/C39940001693

- ↑ B. Wang, X-Y Wu, O. A. Wong, B. Nettles, M-X Zhao, D. Chen and Y. Shi, Helvetica Chimica Acta, 2009, 74(10), 3986-3989; DOI:10.1021/jo900330n