Rep:Mod:shyer

Y3C - Year Three Computational Lab

Week 1

In this experiment, the program GaussView was used to run an optimisation calculation. This uses the Schrödinger equation to calculate the energy of the molecule in question for fixed positions of the nuclei - the SCF calculation. It then varies these positions and recalculates the energy of the system to create a potential energy surface. By several recalculations, the minimum of the potential energy surface can be found - the OPT calculation. This represents the stable configuration of the molecule. At this point, the gradient of the potential energy surface is 0.

GaussView calculates bond lengths to an accuracy of 0.01 Å, bond angles to an accuracy of 0.1°, and energies to an accuracy of 10 kj/mol. There is 10% systematic error on calculated wavenumbers, which are given to the nearest integer.

Day 1

BH3:B3LYP/3-21G

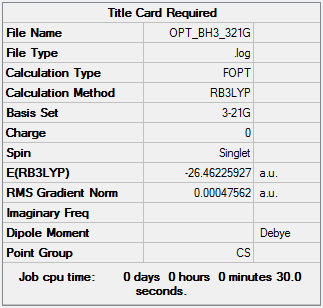

First, a BH3 molecule was optimised. The symmetry of the molecule was distorted, then an OPT calculation was run using a BL3YP method and a 3-21G basis set. The information for the optimised molecule is shown below, and the optimisation file can be accessed here. As seen from the convergence data, the optimisation has been successful. Additionally, it can be determined using GaussView that all three of the stable bond lengths are 1.19 Å, and all the bond angles are 120.0° - the symmetry of the molecule has been repaired.

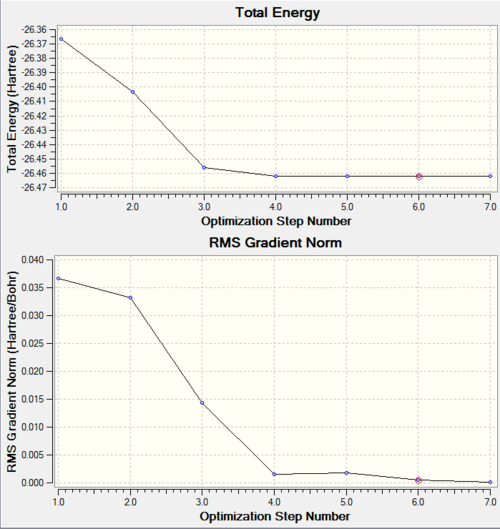

The graphs showing the energy and gradient optimisation are below. As shown, the energy has reached a minimum (-26.46225927 au) and the root mean squared value of the gradient at this point is below 0.001 (0.00047562 au), so is very close to 0.

Day2

Basis sets

In the calculation performed yesterday, a 3-21G basis set was used to perform a basic optimisation. This was a very fast calculation. However, the accuracy was not very high, as seen by the fact that the point group of the optimised molecule was CS, instead of the expected D3h. By using higher basis sets (with more functions involved), the accuracy can be improved.

BH3:B3LYP/6-31G(d,p)

Using the initial optimised molecule as a starting point, another optimisation was carried out on BH3, using a 6-31G(d,p) basis set to give a higher accuracy. The optimisation file can be accessed here. Again, all three optimised bond lengths can be determined to be 1.19 Å, and all angles to be 120.0°. This agrees with the known values.[1]

| Summary | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000444 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000180 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.001100 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000569 0.001200 YES |

|

Pseudo-potentials

BH3 does not have many electrons to consider, so the Schrödinger equation can take into account every electron. However, for larger atoms, the calculation can take a very long time. To reduce the time taken for the calculation, a pseudo-potential can be used to represent all non-valence electrons.

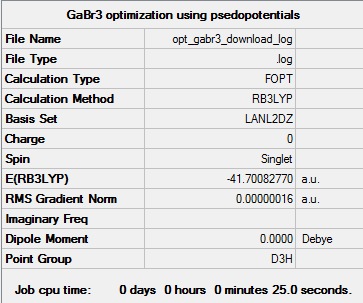

GaBr3:B3LYP/LanL2DZ

A moleucle of GaBr3 was optimised using a LanL2DZ basis set - this uses a pseudo-potential for heavier atoms. The results are shown below, and the optimisation file can be found here: DOI:10042/87707 . The Ga-Br bond distances in the optimised molecule were 2.35 Å and the Br-Ga-Br bond angles were 120°.

| Summary | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000000 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000000 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000003 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000002 0.001200 YES |

|

BBr3:GEN

Next, a moleucle of BBr3 was optimised, using a GEN basis set. This basis set allows different basis sets to be chosen for the different atoms involved, in order to balance a high accuracy with a short calculation. LanL2DZ was used for the heavy Br and 6-31G(d,p) for the lighter B. The results are shown below, and the optimisation file can be found here: DOI:10042/87841 . The B-Br bond distances in the optimised molecule were 1.93 Å and the Br-B-Br bond angles were 120°.

| Summary | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000023 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000013 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000129 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000084 0.001200 YES |

|

Structure comparison

The structures of the three optimised molecules are summarised here:

| BH3 | BBr3 | GaBr3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond distance (Å) | 1.19 | 1.93 | 2.35 |

| Bond angle (°) | 120.0 | 120.0 | 120.0 |

As shown in the table above, changing the ligand or the central element has no effect on the bond angles. This is because all three molecules are trigonal planar, and so all have bond angles of 120.0°. The main difference in structure between the molecules is in the bond distances observed.

While GaussView calculates bond distances by finding the lowest energy structure, and measuring the bond distance from this, the bond distance can also be determined by the Van der Waals radiuses of both atoms involved in the bond - the distance is the sum of the two. So, as the ligand is changed from H in BH3 to Br in BBR3, an increase in bond distance equal to the difference in Van der Waal radiuses of H and Br should be seen. The VdW radius of H is 1.10 Å, while for Br it is 1.87 Å.[2] This is a difference of 0.77 Å, very similar to the observed difference of 0.74 Å. From the longer bond in B-Br, it can be determined that this is the weaker bond. This is due to the size differences of H and Br. H is a small atom, like B. The B-H bond is formed by overlap of the H 1s orbital and the B 2p orbital. These are similar in energy and are also small (therefore have a high electron density). So, the orbitals have a good overlap, and a strong bond is formed. Br, however, is a much larger atom, and the B-Br bond is formed by overlap of the B 2p orbital and Br 4p orbital. As these are very different in energy, and the Br orbital is very large (so has a low electron density), there is less overlap between them and a weaker bond is formed.

While H and Br are different in their size and the strength of the bonds they form to B, they are both monatomic, X-type ligands.

As the central atom is changed from B to Ga, the bond distance is again increased, as Ga is a larger atom with a 4p valence orbital. Again, the increase in atom size leads to an increase in orbital size, a decrease in electron density and therefore a weaker bond.

Both B and Ga have three valence electrons, and therefore form three bonds. In the compounds studied, both B and Ga are in a +3 oxidation state, bonded to three other atoms. In other molecules, Ga can form one bond and exist in the +1 oxidation state, due to the inert pair effect.

Bonds

There are two classes of bonds - intermolecular and intramolecular. Intramolecular bonds can be ionic, covalent or metallic, and are generally much stronger than intermolecular bonds, such as Van der Waals forces and hydrogen bonds. In all cases, the bond consists of a favourable interaction between two atoms. In most cases, this interaction is due to the electrostatic attraction between the nuclei and the electrons. However, in some cases, the interaction is between two dipoles. Bond strength depends on several factors: the extent of orbital overlap (better when the orbitals are similar in size and energy), the electron density of the orbitals involved (higher for smaller orbitals), and the bond order (triple > double > single). Bond strength can also be affected by the electronegativity of the substituents on the atoms involved in the bond (more electronegative substituents draw away electron density and weaken the bond). In the table below, some bonds of different strengths are summarised:[3][4]

| bond strength | bond enthalpy (kJ/mol) | |

|---|---|---|

| N≡N | strong | 946 |

| C-C | medium | 607 |

| Ba-H | weak | 176 |

| hydrogen bond (in bulk water) | very weak | 7.9 |

Once it optimises the positions of the atoms within a molecule, GaussView determines where bonds are drawn based on the distances between atoms in the calculated structure. It compares these calculated distances to predefined data. If these distances fall within a certain range, a bond is drawn. However, bond distances between the same two elements are not always the same between different molecules, as the substituents on the atoms involved can affect the bond strength and therefore length. For example, the C-O bond in (CH3)2O is 141.6 pm, while in CH3OH, the length is increased to 142.8 pm.[5] Due to variations such as this, sometimes a bond will be changed enough in length that it no longer meets the GaussView criteria, and no bond will be drawn, though there may be one.

Day 3

In the previous examples, GaussView has optimised the structure of the molecule by converging to a stationary point on the potential energy surface. However, this stationary point could be a maximum (representing a transition state) rather than a minimum (representing the most stable structure). In order to check that a minimum has been found, vibrational analysis can be carried out.

Frequency and Vibrational Analysis

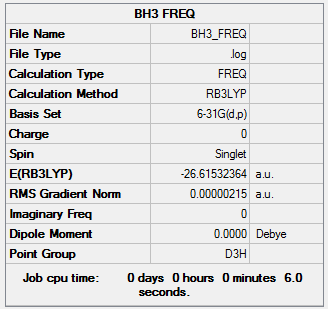

BH3:B3LYP/6-31G(d,p)

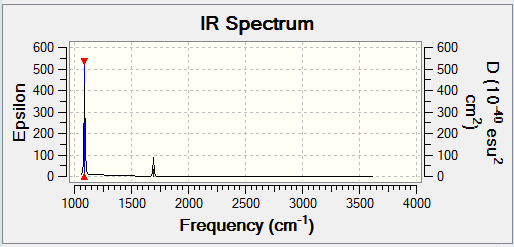

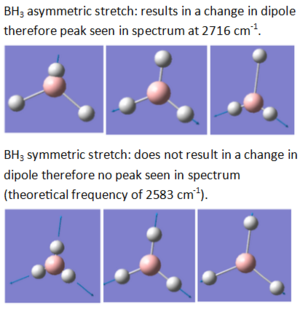

A frequency analysis was carried out on our optimised BH3 molecule. The frequency file can be accessed here.

| Summary Data | Low Modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -11.7227 -11.7148 -6.6070 -0.0010 0.0278 0.4278 Low frequencies --- 1162.9743 1213.1388 1213.1390 |

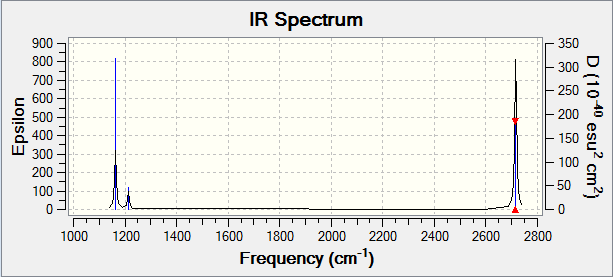

The vibrational modes of the molecule were analysed:

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | IR active? | Type of Vibration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1163 | 93 | YES | bend (umbrella) |

| 1213 | 14 | slightly | bend (rocking) |

| 1213 | 14 | slightly | bend (scissoring) |

| 2583 | 0 | NO | stretch (symmetric) |

| 2716 | 126 | YES | stretch (asymmetric) |

| 2716 | 126 | YES | stretch (asymmetric) |

There are six vibrations, however only three peaks are seen in the IR spectrum. This is due to the fact that one of the vibrations results in no change in dipole, so is not IR active and is not seen. Additionally, of the remaining five vibrations there are two pairs of degenerate vibrations, which show up as two single peaks.

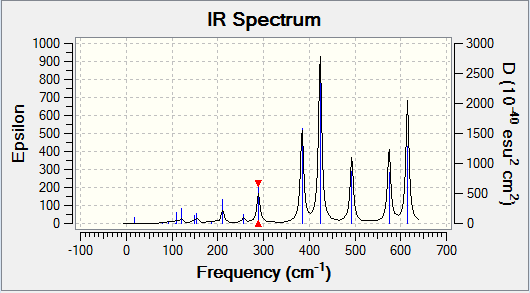

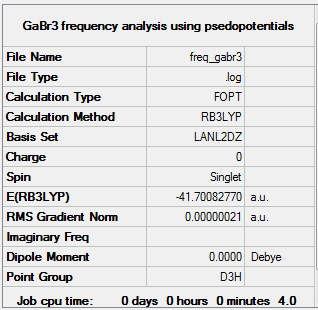

GaBr3:B3LYP/LanL2DZ

A frequency analysis was also carried out on our optimised GaBr3 molecule. The frequency file can be accessed here.

| Summary Data | Low Modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -1.4877 -0.0015 -0.0002 0.0096 0.6540 0.6540 Low frequencies --- 76.3920 76.3924 99.6767 |

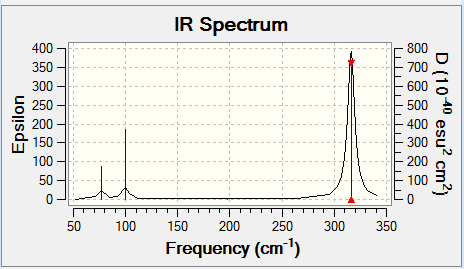

The vibrational modes of the molecule were analysed:

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | IR active? | Type of Vibration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 76 | 3 | slightly | bend (rocking) |

| 76 | 3 | slightly | bend (scissoring) |

| 100 | 9 | slightly | bend (umbrella) |

| 197 | 0 | NO | stretch (symmetric) |

| 316 | 57 | YES | stretch (asymmetric) |

| 316 | 57 | YES | stretch (asymmetric) |

Again, due to degeneracy and IR activity, only three peaks are seen despite the six vibrations.

Comparison: GaBr3 and BH3

Both GaBr3 and BH3 are trigonal planar molecules, so both have 6 vibrational modes, according to the 3n-6 rule. These comprise of a symmetric stretch, two asymmetric stretches, a rocking mode, a scissoring mode, and an umbrella motion. However, while the number and types of vibrations are the same for both molecules, and both IR spectra show three peaks, the wavenumbers corresponding to each stretch are different.

All of the wavenumbers are much higher for BH3 than GaBr3; this demonstrates the fact that the B-H bonds are stronger than the Ga-Br bonds, and so take more energy to vibrate. This, as discussed before, is due to the higher electron density for the smaller atoms.

For both molecules, the stretches are at higher wavenumbers than the bends, and the degenerate asymmetric stretches are the highest energy vibrations. For the bends, there are more differences between the molecules. In BH3, the vibrations increase in energy from the umbrella mode to the degenerate rocking and scissoring modes. In GaBr3, the vibrations increase in energy from scissoring and rocking to the umbrella mode.

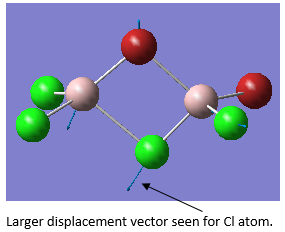

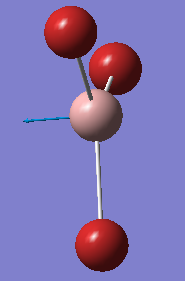

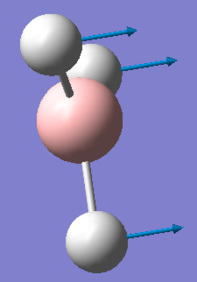

This is due to the fact that the GaBr3 umbrella vibration requires more energy than the BH3 umbrella vibration, in comparison to the other vibrations for each molecule. As seen in the animation by GaussView, for BH3 the main displacement is by the H atoms. As these are very light, this takes little energy. In GaBr3, however, the displacement is by the Ga atom. As this is so much heavier, it takes a lot more energy. The displacements are shown below.

| GaBr3 | BH3 |

|---|---|

|

|

As well as the difference in energy, the umbrella mode is much more intense for the BH3 molecule than the GaBr3 molecule, due to the larger change in dipole in the BH3 vibration. While the difference in electronegativity between Ga and Br is greater than the difference between B and H,[6] the displacement in the BH3 vibration is much larger, so there is a larger change in dipole for this molecule.

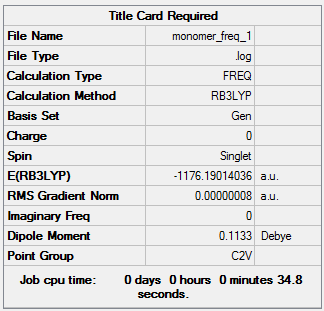

Frequency Analysis Methods

The same basis set and method must be used for both the optimisation and frequency analysis calculation in order to ensure that the same structure is being analysed. This can be further verified by checking the energies of the structures - the energy of the optimised structure and the structure used for frequency analysis should be the same. This can be seen in the calculations performed - there is no difference in energy for the two GaBr3 structures and the difference in energy of the two BH3 molecules is 0.00000049 au - within the range of error of the program.

A frequency analysis allows the slope of the potential energy surface to be determined, to check that a minimum has been found, and therefore the structure of the molecule has been optimised. This is a necessary check, as there are stationary points on the potential energy surface which do not correspond to the lowest energy configuration of the molecule.

The "Low frequencies" given in the table are the movements of the centre of mass of the molecule. They provide information about the accuracy of the frequency calculation - the closer to 0 they are, the more accurate the calculation. If none of the low frequencies are above 15 cm-1, there is an acceptable level of accuracy.

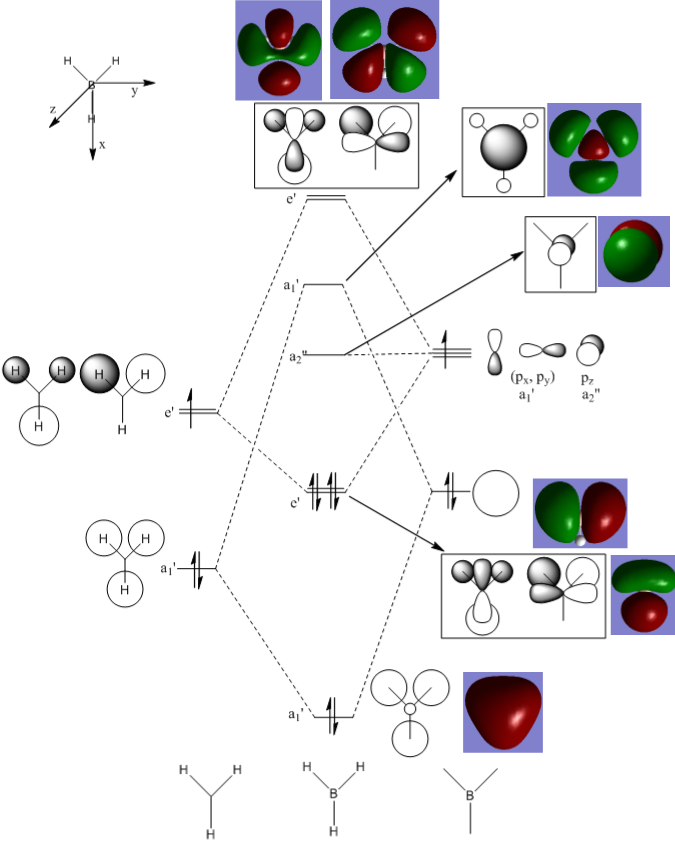

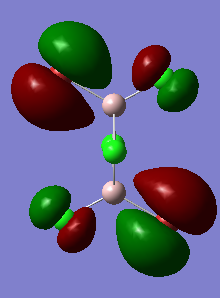

Molecular Orbitals

GaussView allows the molecular orbitals of a molecule to be calculated - this calculation was carried out for the optimised BH3 molecule. The log file can be accessed here: DOI:10042/92900 . These calculated orbitals can be compared to the orbitals predicted using the LCAO approximation.

In comparing the expected and calculated MOs, some similarities and some differences can be seen. While the LCAO theory provides a good basis for the calculated MOs, the calculated MOs combine all the orbitals. This can result in a quite different shape to that expected, for example in the highest energy orbitals shown. Additionally, the contribution of the different orbitals to the MOs is somewhat different between the expected and calculated orbitals. For example, the a1' antibonding orbital shown has a large contribution from all orbitals involved, where only a small contribution from the H orbitals was expected.

So, while qualitative MO theory is a very useful tool, allowing the relative energies and rough shapes of the MOs to be predicted, it is not very accurate, especially for more complex orbitals.

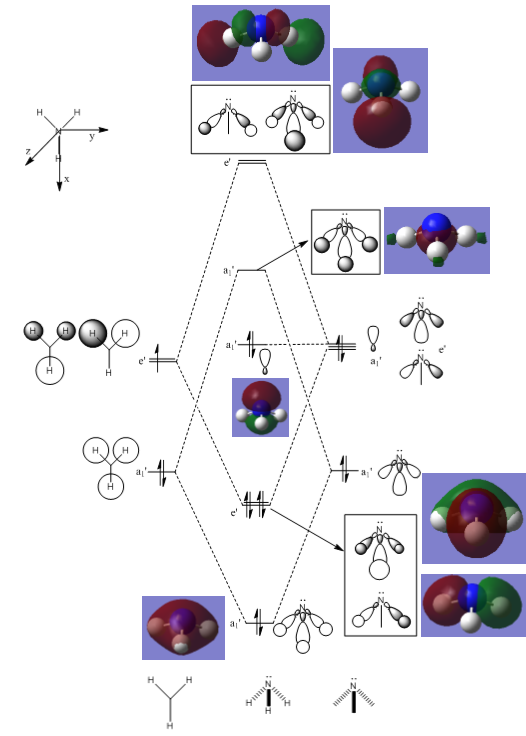

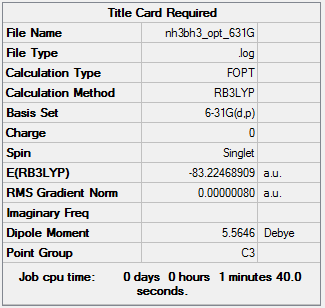

NH3:B3LYP/6-31G(d,p)

Optimisation

A molecule of NH3 was optimised using a 6-31G basis set, optimisation file here.

| Summary | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000006 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000004 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000012 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000008 0.001200 YES |

|

Frequency Analysis

A frequency test was carried out on the optimised molecule. This showed that an accurate minimum had been reached, as all the first line low frequencies are close to zero, and all the second line low frequencies are positive. The frequency file can be accessed here.

| Summary Data | Low Modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -0.0137 -0.0025 -0.0010 7.0781 8.0927 8.0932 Low frequencies --- 1089.3840 1693.9368 1693.9368 |

The vibrational modes of the molecule were analysed:

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | IR active? | Type of Vibration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1089 | 145 | YES | bend (umbrella) |

| 1694 | 14 | slightly | bend (rocking) |

| 1694 | 14 | slightly | bend (scissoring) |

| 3461 | 1 | NO | stretch (symmetric) |

| 3590 | 0 | NO | stretch (asymmetric) |

| 3590 | 0 | NO | stretch (asymmetric) |

Molecular Orbitals

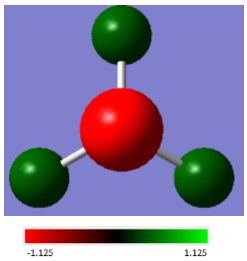

A population analysis was carried out to determine the MOs of the NH3 molecule. The log file can be accessed here: DOI:10042/93163 .

Natural Bond Orbital Analysis (NBO)

As shown below, GaussView can be used to determine the charges of the different atoms in our molecule. The scale used is from -1.125 to 1.125 au - the electronegative N atom has a charge of -1.12514, while the H atoms each have a charge of 0.37505.

Day 4

NH3BH3

Optimisation of NH3BH3:B3LYP/6-31G(d,p)

A molecule of NH3BH3 was optimised. So that it can be compared with the NH3 and BH3 molecules already analysed, the same method and basis set was used. The optimisation file can be accessed here.

| Summary | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000003 0.000015 YES RMS Force 0.000001 0.000010 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000018 0.000060 YES RMS Displacement 0.000010 0.000040 YES |

|

The optimisation was checked by carrying out a frequency test on the optimised molecule. The frequency file can be accessed here.

| Summary Data | Low Modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -0.0759 -0.0292 -0.0144 3.7967 3.9207 7.7606 Low frequencies --- 263.6126 632.9815 638.6073 |

Calculation of Bond Energies

| Molecule | Energy (au) |

|---|---|

| BH3 | -26.61532315 |

| NH3 | -56.55776873 |

| NH3BH3 | -83.22468909 |

Using the energies of the different molecules, the dissociation energy of NH3BH3 can be calculated.

ΔE = E(NH3BH3)-[E(NH3)+E(BH3)]

ΔE = (-83.22468909)-[(-56.55776873)+(-26.61532315)]

ΔE = -0.05159721 au

This converts to an N-H bond energy of 135.47 kJ/mol. From the bond strengths quoted earlier, it can be seen that this is clearly a intramolecular bond. However, it is a very weak intramolecular bond.

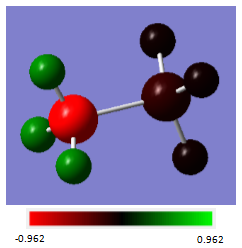

NBO analysis of NH3BH3

A population analysis was run on the optimised NH3BH3 molecule, and from this the charge distribution was determined:

| Atom | Charge(au) |

|---|---|

| N | -0.962 |

| H (bonded to N) | 0.436 |

| B | -0.171 |

| H (bonded to B) | -0.059 |

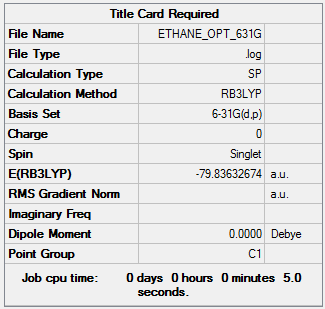

Ethane

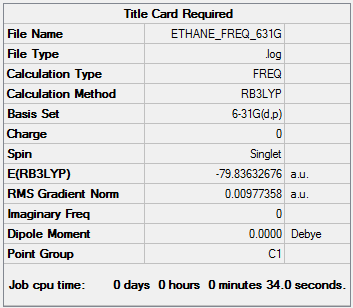

Optimisation of ethane:B3LYP/6-31G(d,p)

A molecule of ethane was optimised. The optimisation file can be accessed here.

| Summary | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000198 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000038 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000390 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000117 0.001200 YES |

|

The optimisation was checked by carrying out a frequency test on the optimised molecule. The frequency file can be accessed here.

| Summary Data | Low Modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -0.0005 -0.0005 0.0001 89.6275 89.9392 422.8671 Low frequencies --- 542.0011 925.9096 926.0301 |

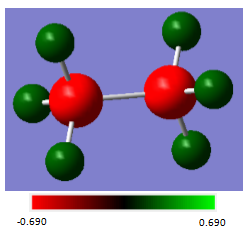

NBO analysis of ethane

A population analysis was run on the optimised ethane molecule, and from this the charge distribution was determined:

| Atom | Charge(au) |

|---|---|

| C | -0.690 |

| H | 0.230 |

Comparison: aminoborane and ethane

Though aminoborane and ethane are isoelectronic, there are major differences in the charge distribution across each molecule. These can be explained by looking at the electronegativities of the atoms involved in each molecule (summarised below).[6]

| Atom | Electronegativity |

|---|---|

| C | 2.55 |

| H | 2.10 |

| N | 3.04 |

| B | 2.04 |

In ethane, the charge distribution is symmetrical. The C atoms both have the same negative charge, and all six of the H atoms have the same positive charge. The H atoms have one third the charge that the C atoms have, as the overall molecule is neutral. This corresponds to the difference in electronegativity of C and H - as C is more electronegative, it attracts the electrons slightly towards it.

In aminoborane, the charge distribution is highly asymmetrical. As the most electronegative atom, the N has a large negative charge. Due to the large difference in electronegativity between the H and N atoms, the H atoms bonded to the N have a positive charge. While N is more electronegative than B, and therefore attracts electron density away from B, it is also donating electron density through the dative bond. Therefore the BH3 group is close to neutral. B and H are very similar in electronegativity, so there is very little difference in charge between B and the H atoms bonded to it.

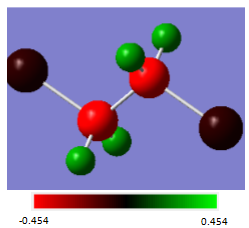

Effects of substituents

Ethane

To alter the charges on the atoms, their substituents can be changed. In the example below, one of the H atoms on each C atom in the ethane molecule has been replaced with Cl. As Cl is more electronegative than H, this change has increased the charge on C from -0.690 to -0.454.

| Atom | Charge(au) |

|---|---|

| C | -0.454 |

| H | 0.264 |

| Cl | -0.075 |

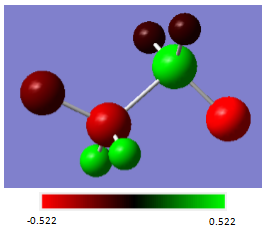

Aminoborane

The same effect can be seen in aminoborane. As N is more electronegative than C, and as electronegative as Cl, a more electronegative atom must be used as a subtituent. By replacing two H atoms, one on B and one on N, with F, similar changes in charge are seen as for the substituted ethane - both the N and the B atoms increase in charge (-0.962 to -0.364 and -0.171 to 0.456 respectively) as electron density is drawn away from them. This also has the effect of drawing electron density away from the B-N bond, weakening it. This can be seen in the increase in B-N bond length from 1.67 Å in aminoborane to 1.69 Å in 1,2-difluoroaminoborane.

| Atom | Charge(au) |

|---|---|

| B | 0.456 |

| H (on B) | -0.107 |

| F (on B) | -0.522 |

| N | -0.364 |

| H (on N) | 0.429 |

| F (on N) | -0.214 |

Week 2: Lewis Acids and Bases

Background

Group 13 elements only have 3 unpaired electrons, so can only form three covalent bonds. However, this leaves them with only six electrons in their valence orbital; they form electron deficient compounds. Due to this, many compounds formed by group 13 elements are Lewis acids, and are very good electron acceptors.

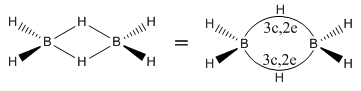

One example of this is BH3. This is so electron deficient that it forms dimers with bridging H atoms, with 3c,2e bonds.

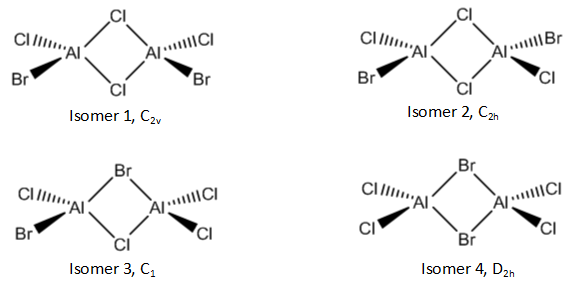

Al, as a group 13 element, forms similarly electron deficient compounds. In this experiment, the dimers formed by the AlCl2Br monomer will be investigated.

Al2Cl4Br2 dimer

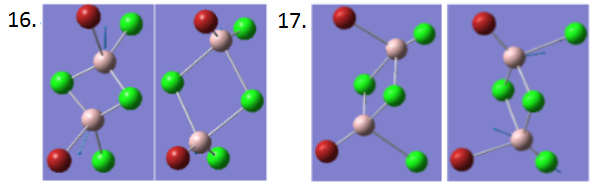

The AlCl2Br molecule has four different isomers for its dimer:

Each of these isomers was optimised, and a frequency analysis and vibrational analysis were carried out. A B3LYP/GEN method was used, with a 6-31G(d,p) basis set for Al and Cl, and a LANL2DZ basis set for Br.

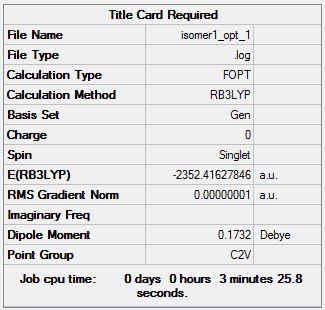

Isomer 1:B3LYP/GEN

The optimisation file can be accessed here: DOI:10042/98452 .

| Summary | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000000 0.000015 YES RMS Force 0.000000 0.000010 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000002 0.000060 YES RMS Displacement 0.000001 0.000040 YES |

|

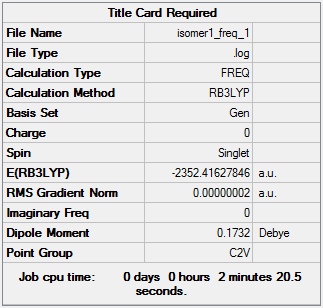

The frequency file can be accessed here: DOI:10042/98467 .

| Summary Data | Low Modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -1.3334 -0.7714 -0.0017 -0.0017 -0.0014 2.2147 Low frequencies --- 17.4968 51.1457 78.5265 |

Finally, a vibrational analysis was carried out.

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | IR active? | Type of Vibration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | 0 | NO | bend |

| 51 | 0 | NO | bend |

| 79 | 0 | NO | bend |

| 99 | 0 | NO | bend |

| 103 | 3 | NO | bend |

| 121 | 13 | very slightly | bend |

| 123 | 6 | very slightly | bend |

| 157 | 0 | NO | bend |

| 158 | 5 | very slightly | bend |

| 194 | 2 | NO | bend |

| 263 | 0 | NO | stretch |

| 279 | 26 | slightly | stretch |

| 308 | 2 | NO | stretch |

| 413 | 149 | YES | stretch |

| 420 | 410 | YES | stretch |

| 461 | 35 | slightly | stretch |

| 571 | 33 | slightly | stretch |

| 583 | 277 | YES | stretch |

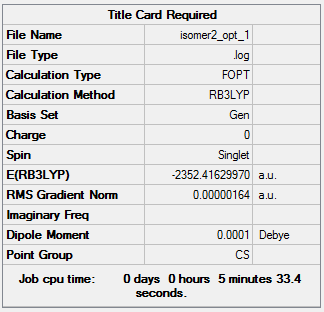

Isomer 2:B3LYP/GEN

The optimisation file can be accessed here: DOI:10042/98525 .

| Summary | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000002 0.000015 YES RMS Force 0.000001 0.000010 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000059 0.000060 YES RMS Displacement 0.000017 0.000040 YES |

|

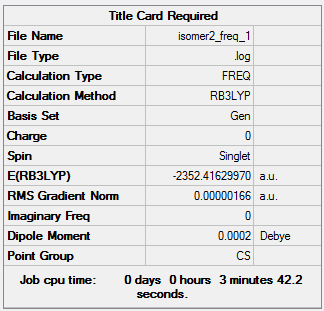

The frequency file can be accessed here: DOI:10042/98538 .

| Summary Data | Low Modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -1.8585 -1.5522 -1.1951 -0.0015 0.0010 0.0028 Low frequencies --- 18.1836 49.1549 72.8916 |

Finally, a vibrational analysis was carried out.

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | IR active? | Type of Vibration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | 0 | NO | bend |

| 49 | 0 | NO | bend |

| 73 | 0 | NO | bend |

| 105 | 0 | NO | bend |

| 109 | 0 | NO | bend |

| 117 | 7 | very slightly | bend |

| 120 | 13 | very slightly | bend |

| 157 | 0 | NO | bend |

| 159 | 6 | very slightly | bend |

| 192 | 0 | NO | bend |

| 263 | 0 | NO | stretch |

| 280 | 29 | very slightly | stretch |

| 308 | 0 | NO | stretch |

| 413 | 149 | YES | stretch |

| 421 | 438 | YES | stretch |

| 459 | 0 | NO | stretch |

| 575 | 0 | NO | stretch |

| 580 | 316 | YES | stretch |

Isomer 3:B3LYP/GEN

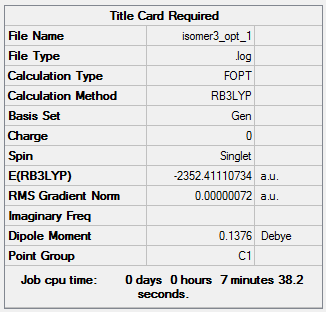

The optimisation file can be accessed here: DOI:10042/98577 .

| Summary | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000001 0.000015 YES RMS Force 0.000000 0.000010 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000021 0.000060 YES RMS Displacement 0.000007 0.000040 YES |

|

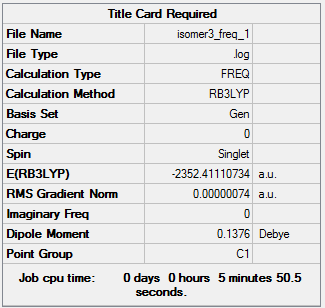

The frequency file can be accessed here: DOI:10042/98588 .

| Summary Data | Low Modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -0.0002 0.0019 0.0024 0.1693 1.1161 1.8031 Low frequencies --- 16.9434 55.9193 80.0644 |

Finally, a vibrational analysis was carried out.

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | IR active? | Type of Vibration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 17 | 0 | NO | bend |

| 56 | 0 | NO | bend |

| 80 | 0 | NO | bend |

| 92 | 1 | NO | bend |

| 107 | 0 | NO | bend |

| 110 | 5 | very slightly | bend |

| 121 | 8 | very slightly | bend |

| 149 | 5 | very slightly | bend |

| 154 | 6 | very slightly | bend |

| 186 | 1 | NO | bend |

| 211 | 21 | slightly | stretch |

| 257 | 10 | very slightly | stretch |

| 289 | 48 | slightly | stretch |

| 384 | 153 | YES | stretch |

| 424 | 274 | YES | stretch |

| 493 | 107 | YES | stretch |

| 575 | 122 | YES | stretch |

| 615 | 197 | YES | stretch |

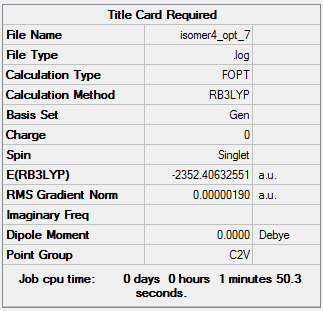

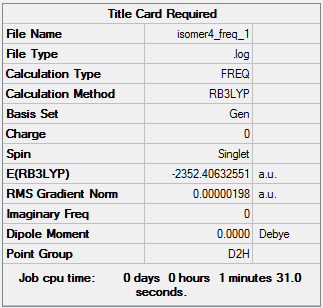

Isomer 4:B3LYP/GEN

The optimisation file can be accessed here: DOI:10042/98400 .

| Summary | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000004 0.000015 YES RMS Force 0.000002 0.000010 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000058 0.000060 YES RMS Displacement 0.000025 0.000040 YES |

|

The frequency file can be accessed here: DOI:10042/98416 .

| Summary Data | Low Modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -0.7169 0.0019 0.0029 0.0039 1.4582 1.5115 Low frequencies --- 16.0921 63.6277 86.1112 |

Finally, a vibrational analysis was carried out.

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | IR active? | Type of Vibration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | 0 | NO | bend |

| 64 | 0 | NO | bend |

| 86 | 0 | NO | bend |

| 87 | 0 | NO | bend |

| 108 | 5 | very slightly | bend |

| 111 | 0 | NO | bend |

| 126 | 8 | very slightly | bend |

| 135 | 0 | NO | bend |

| 138 | 7 | very slightly | bend |

| 163 | 0 | NO | bend |

| 197 | 0 | NO | stretch |

| 241 | 100 | YES | stretch |

| 247 | 0 | NO | stretch |

| 341 | 160 | YES | stretch |

| 468 | 346 | YES | stretch |

| 494 | 0 | NO | stretch |

| 609 | 0 | NO | stretch |

| 617 | 332 | YES | stretch |

Discussion - Relative Energies

| Isomer | Energy (au) | Energy (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | -2352.41627846 | -6176269.41 |

| 2 | -2352.41629970 | -6176269.47 |

| 3 | -2352.41110734 | -6176255.83 |

| 4 | -2352.40632551 | -6176243.28 |

By comparison of the energies of the different isomers, it can be seen that isomer 2 has the lowest energy, and so is the most stable. In the table below, the difference in energy of each isomer from isomer 2 is listed.

| Isomer | Difference in Energy from Isomer 2 (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 0.06 |

| 2 | 0.00 (most stable isomer) |

| 3 | 13.64 |

| 4 | 26.19 |

Isomer 1 and 2 are very similar in their energies, while isomer 3 and 4 are higher in their energies. From this it can be determined that the main difference in energy is determined by which ligands are bridging, and which are terminal. If the stability was determined by the symmetry of the molecule, isomer 1 and 2 would be more different in energy. Additionally, it can be calculated that the energy difference for isomer 4 is roughly twice that for isomer 3. From this, it can be concluded that a Br dative bond is roughly 13 kJ/mol weaker than a Cl dative bond.

In order to understand why this is, the two bonds formed must be examined. In the AlCl2Br monomer, Al is sp2 hybridised, with bond angles of 120°. The Cl-Al or Br-Al dative bonds are formed by the donation of the Cl lone pair (from the 2p orbital) or the Br lone pair (from the 3p orbital) to the electron deficient Al. This can be confirmed by the bond angles. In isomer 1, for example, the Al-Cl-Al bond angle is 89.8°, indicating the angle between two p-orbitals. The bond angles around the Al vary somewhat. Due to the Al-Cl-Al bond angles, the Cl-Al-Cl bond angles are also forced to roughly 90° (90.2° exactly). The two terminal ligands roughly maintain their 120° bond angle, though it is slightly increased to 121.5°. The angle between the terminal and bridging ligands is therefore roughly 110°, in order to keep separation between the bonds at a maximum. Similar bond angles are seen in all the ligands.

The different bond strength are due to the size and energy difference of Br and Cl. As both Al and Cl are in the third row of the periodic table, they are similar in size. This means that their orbitals have a good overlap, and a strong bond can be formed. Br is in the fourth row of the periodic table. Due to this, it has larger orbitals. These have a lower electron density, and also have a worse overlap with the Al orbitals, leading to a weaker bond. Additionally, the Br lone pair is in a higher energy orbital than the Cl lone pair. This means that there is a larger difference in energy between the Al and Br orbitals compared to the energy difference between the Al and Cl orbitals. This larger energy gap leads to less stabilisation when the bond is formed, and therefore a weaker bond.

This trend might not be expected. As Br is less electronegative than Cl, it might be expected to form more stable bridging ligands. However, the difference in electronegativity is so slight that this is not a major effect.[6]

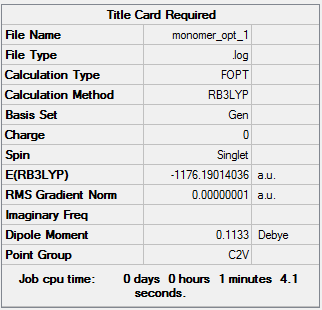

Dissociation Energy

Using the same basis set (B3LYP/GEN), the AlCl2Br monomer was optimised. The optimisation file can be accessed here: DOI:10042/107328 .

| Summary | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000000 0.000015 YES RMS Force 0.000000 0.000010 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000000 0.000060 YES RMS Displacement 0.000000 0.000040 YES |

|

The frequency file can be accessed here: DOI:10042/107335 .

| Summary Data | Low Modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -0.0036 0.0007 0.0036 1.8664 1.8732 3.5921 Low frequencies --- 120.7378 133.8464 185.7655 |

From these results, it can be determined that two monomers are 0.03601898 au (94.57 kJ/mol) higher in energy than isomer 2 (calculation shown below). This shows that the dimer is more stable than the monomers, and explains why it is spontaneously formed.

Calculation:

ΔE = E(dimer)-2*E(monomer)

ΔE = (-2352.41629970)-[2*(-1176.19014036)]

ΔE = -0.03601898 au

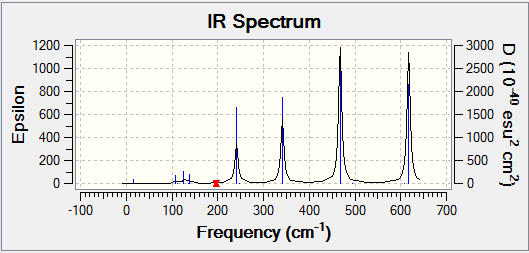

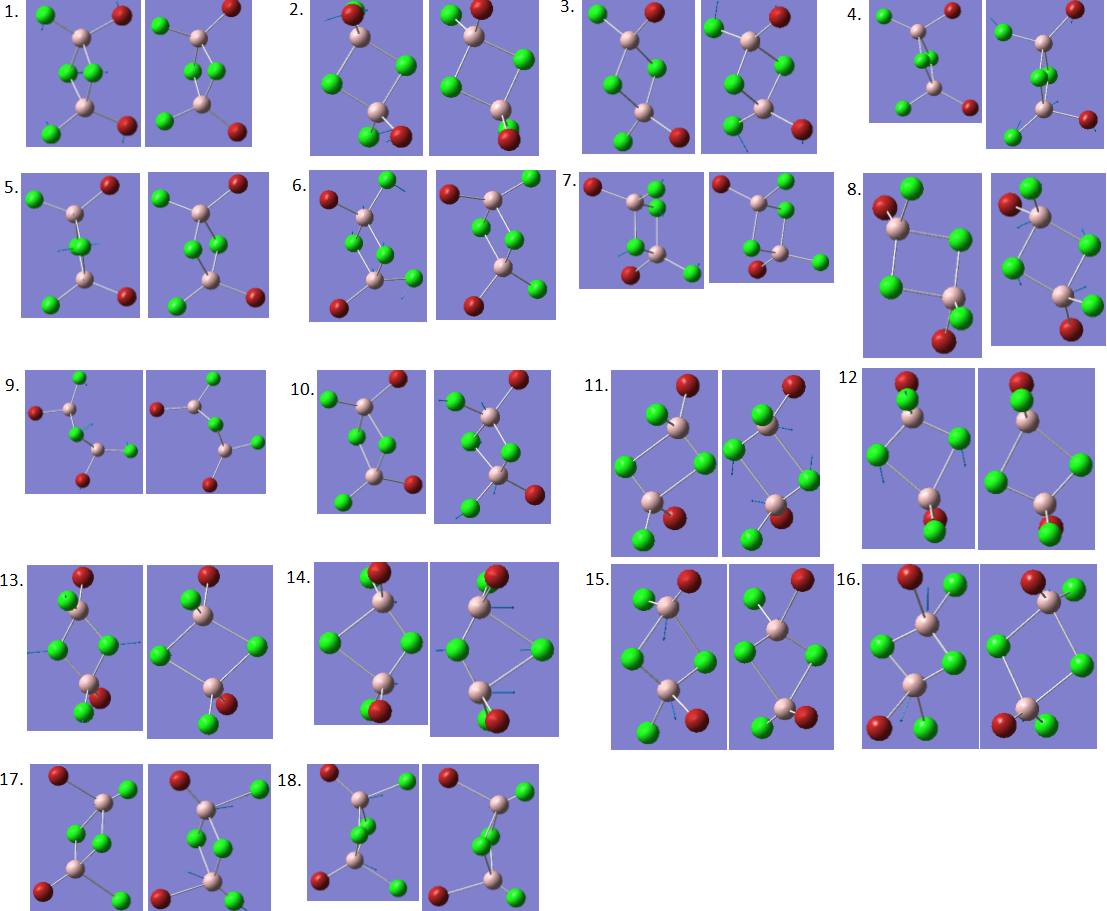

Discussion - IR spectra of Dimers

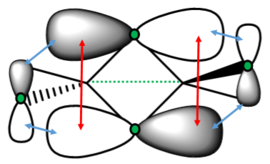

There are two main differences in the IR spectra calculated for the four isomers – the different numbers of peaks visible and the different energies of the vibrational modes. Both of these differences will be discussed. Below are shown the 18 vibrational modes for Isomer 1. Similar modes were seen for all isomers. The modes have been numbered 1-18 below, and in further discussion, these numbers will be used to describe each mode. This picture is included in order to give an idea of the movement involved in each vibration. Remember that while the modes are the same between each isomer, there are differences in the exact movements of atoms.

IR activity

In order to be IR active, a vibrational mode must result in a change in dipole. This was seen earlier, in the IR spectrum of BH3. Two examples of BH3 vibrational modes are shown below - one results in a change in dipole (the asymmetric stretch), while the other does not (the symmetric stretch). This can be confirmed by the IR spectrum of BH3 (shown below), in which a peak is seen for the asymmetric stretch, but not for the symmetric one.

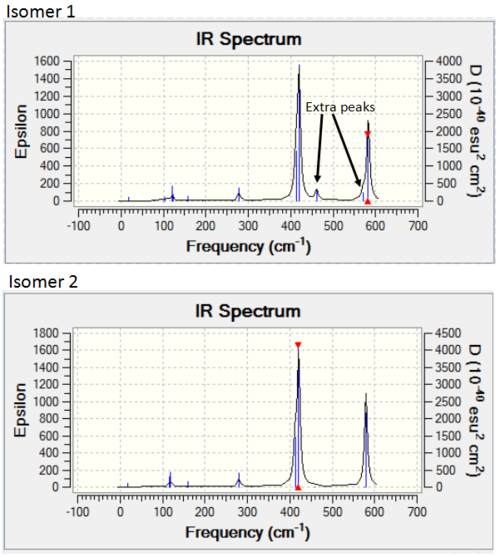

Numbers of peaks

As described, in order to be seen on a spectra, a vibration must result in a change in dipole. The different isomers, though they have the same vibrational modes, have their atoms in different positions, so have different dipoles. Due to this, different numbers of peaks are seen in the IR spectra for each isomer. While all the isomers have 18 vibrational modes (10 bends and 8 stretches), between 7 and 12 peaks are seen in the spectra, with varying intensity. Below is a summary of the modes seen for all of the isomers, with a description of the IR activity of each mode for each isomer.

| Mode | Isomer 1 | Isomer 2 | Isomer 3 | Isomer 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| 2 | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| 3 | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| 4 | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| 5 | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| 6 | very slightly | very slightly | very slightly | very slightly |

| 7 | very slightly | very slightly | very slightly | very slightly |

| 8 | NO | NO | very slightly | NO |

| 9 | very slightly | very slightly | very slightly | very slightly |

| 10 | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| 11 | NO | NO | slightly | NO |

| 12 | slightly | very slightly | slightly | YES |

| 13 | NO | NO | very slightly | NO |

| 14 | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| 15 | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| 16 | slightly | NO | YES | NO |

| 17 | slightly | NO | YES | NO |

| 18 | YES | YES | YES | YES |

While the vibrational modes all cause some change in dipole across parts of the molecule, if the symmetry of the molecule is the same as the symmetry of the vibration, the dipoles in the different parts of the molecule will cancel to produce no net change in dipole. Therefore, the most symmetrical isomers (2 and 4) are expected to have the fewest visible peaks, while the more asymmetrical isomers (1 and 3) are expected to have more visible peaks, due to the higher chance of a vibration resulting in a change in dipole. As isomer 3 is the most asymmetrical, it is expected to have the most peaks. This is the case:

| Isomer | Number of Visible Peaks |

|---|---|

| 1 | 9 |

| 2 | 7 |

| 3 | 12 |

| 4 | 7 |

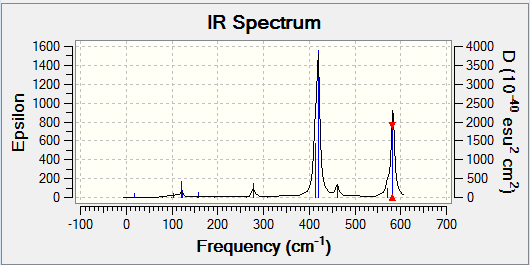

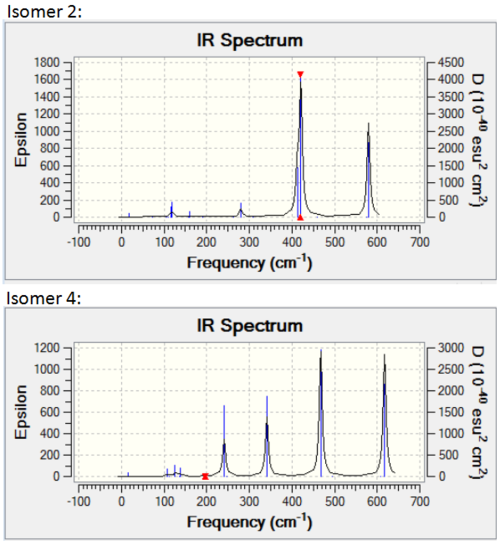

Isomer 2 and isomer 4 are have the point groups C2h and D2h respectively – they have a high symmetry. This means that even if a vibration causes a change in dipole across part of the molecule, the change will be mirrored across the molecule, and as a result there will be no overall change in dipole. Due to this, many of the vibrational modes for these isomers are not IR active. From the table above, it can be seen that the same modes are active and inactive for both these isomers. However, while their spectra are similar in the number of peaks seen, the peaks have a varying intensity. Both spectra can be seen below.

Isomer 1 is also quite symmetrical. In general, it has the same active and inactive modes as isomers 2 and 4. However, mode 16 and 17 are active for isomer 1, while they are inactive for isomers 2 and 4. These modes are shown again below.

It can be seen that both of these modes have a C2 symmetry (down the centre of the molecule) in their vibration. As both isomer 2 and 4 have a C2 axis down the centre, the change in dipole caused by the vibration is equal across both sides of the molecule and therefore there is no net change. For isomer 1, which does not have this axis of symmetry, there is a net change in dipole, so peaks are seen. These peaks do not have a high intensity, as the change in dipole is slight.

Apart from these extra peaks, the spectrum for isomer 1 is very similar to that for isomer 2. Both spectra are shown below.

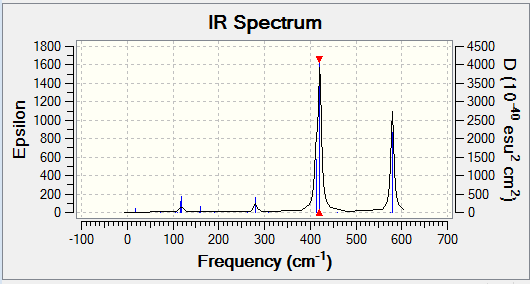

Isomer 3 has a C1 point group, so is highly asymmetrical. This means that the majority of the vibrations cause a change in dipole - 12 out of the 18. However, many of these changes in dipole are small, and so many of the peaks have a low intensity. The IR spectrum for isomer 3 is shown below.

Relative energies of peaks

All four isomers have a similar range in frequency of vibrations, as all contain the same bonds of the same strength. However, there are some differences in the energies of certain vibrations. Below is a table listing the modes, and the frequency seen for each isomer for these modes. Additionally, the range (difference in wavenumber for the highest and lowest absorption) has been calculated.

| Mode | Isomer 1 | Isomer 2 | Isomer 3 | Isomer 4 | Range (cm-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18 | 18 | 15 | 16 | 3 |

| 2 | 51 | 49 | 56 | 64 | 15 |

| 3 | 79 | 73 | 80 | 87 | 15 |

| 4 | 99 | 105 | 107 | 111 | 12 |

| 5 | 103 | 109 | 92 | 86 | 15 |

| 6 | 121 | 120 | 121 | 126 | 6 |

| 7 | 123 | 117 | 110 | 108 | 15 |

| 8 | 157 | 157 | 149 | 135 | 22 |

| 9 | 158 | 159 | 154 | 138 | 20 |

| 10 | 194 | 192 | 186 | 163 | 31 |

| 11 | 263 | 263 | 211 | 197 | 66 |

| 12 | 279 | 280 | 289 | 241 | 57 |

| 13 | 308 | 308 | 257 | 247 | 61 |

| 14 | 413 | 413 | 384 | 341 | 72 |

| 15 | 420 | 421 | 424 | 468 | 48 |

| 16 | 461 | 459 | 493 | 494 | 35 |

| 17 | 571 | 575 | 575 | 609 | 38 |

| 18 | 583 | 580 | 615 | 617 | 37 |

From the table above, it can be calculated that the average range of the vibrational modes is 28.2 cm-1. However, the average difference between isomer 1 and 2 is only 2.3 cm-1. From this it can be concluded that the main effect on the frequency of vibrations is due to which ligands are bridging and terminal, as both isomer 1 and 2 have the same bridging and terminal ligands.

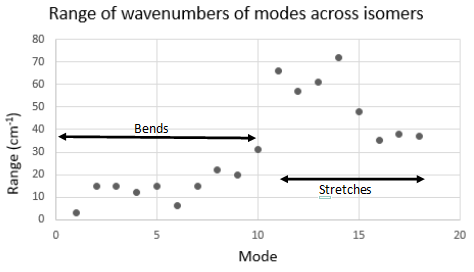

From the graph above, it can be seen that there is not much difference between the wavenumber values for the bending modes, and there is a much larger difference between the wavenumber values for the stretching modes. Due to this, only the stretching modes will be analysed. Additionally, it can be seen that there is a higher difference in wavenumber values for the first 4 stretching modes, and a smaller difference in wavenumber values for the last 4 stretching vibrations.

By observing the vibrations (pictured earlier), the difference between modes 11-14 and modes 15-18 can be seen. In modes 11-14, the bond lengths to the terminal ligands are roughly unchanged by the vibration, while the bridging bonds are stretched and compressed. In modes 15-18, the bond lengths to the terminal ligands are stretched and compressed, and the bridging bond lengths are roughly unchanged.

Modes 11-14: As discussed earlier, the bond strength of the dative Al-Cl and Al-Br bonds are different. Due to this, it requires different amounts of energy to stretch and compress these bridging bonds, leading to the change in the frequency of the vibration calculated. As the Al-Cl bond is stronger, it would be expected that isomers containing more Cl bridging ligands would have higher wavenumbers than isomers with bridging Br atoms. So, the expected trend is equal, high wavenumbers for isomers 1 and 2 (with 2 bridging Cl), a lower wavenumber for isomer 3 (with one bridging Cl and one bridging Br) and the lowest wavenumber for isomer 4 (with 2 bridging Br). This trend is observed for modes 11, 13 and 14. Mode 12 has a similar trend, though isomer 3 has roughly the same energy vibration as isomer 1 and 2. By examining the mode, it can be seen that this is due to the different size of the Br and Cl atoms; the Br atom is heavier, so is displaced less, increasing the displacement of the Cl bridging atom and increasing the energy of the vibration.

Modes 15-18: In modes 15 to 18, an opposite trend would be expected. Isomer 1 and 2, with their bridging Cl, have more terminal Br, so weaker terminal bonds which are more easily stretched and compressed, leading to a lower wavenumber vibration. So, the expected trend for these modes is a high energy vibration for isomer 4 (with the most terminal Cl), a lower energy vibration for isomer 3, and equal, lowest energy vibrations for isomers 1 and 2. As seen in the table, this trend is observed.

Finally, it can be seen that the effect of the different bridging ligands is stronger than the effect of the different terminal ligands, as modes 11-14 vary more in energy than modes 15-18 (see graph above).

Molecular Orbitals - Isomer 2

A population analysis was carried out on isomer 2 (basis set:B3LYP/GEN, log file here: DOI:10042/112235 ), producing 54 occupied molecular orbitals. 30 of these were core orbitals, consisting of unmixed atomic orbitals. Out of the 24 remaining occupied, non-core molecular orbitals, 5 have been analysed below, ranging from strongly bonding to strongly antibonding.

Annotated diagrams are shown for each molecular orbital, showing both the molecular orbital determined by the Gaussian calculation, and also the atomic orbitals most likely to be contributing to it. In some examples the Gaussian calculated MO is shown from several angles for clarity.

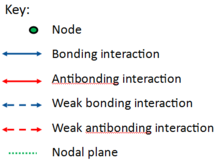

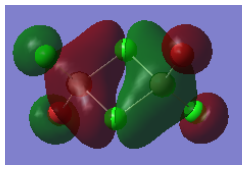

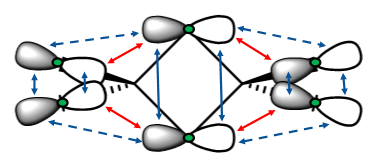

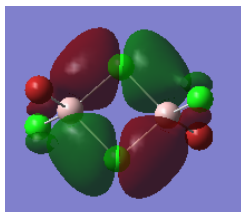

Molecular Orbital 37 - strongly bonding

This molecular orbital is comprised of the p-orbitals on the Cl (3p) and Br (4p) atoms, and the 3s orbitals on the Al. The atomic orbitals contribute roughly equally to the molecular orbital. There are very strong bonding interactions between all the orbitals on either side, forming two large sections of overlap, encompassing 5 atoms each - this MO is highly delocalised. This could be due to the electron deficient Al attracting electron density towards it. These large sections of overlap can be clearly seen in the Gaussian calculated MO above. There are a few antibonding interactions seen - a strong interaction between the two large delocalised sections just described, and a weak through space interaction between the bridging and terminal ligands. As these are much weaker than the bonding interaction, overall this is a strongly bonding MO. The only nodes seen in this MO are the six lesser nodes on the halogen atom centres.

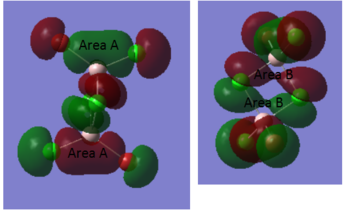

Molecular Orbital 43 - bonding

This molecular orbital is comprised of the p-orbitals on the Cl (3p) and Br (4p), with no contribution from the Al atoms. The atomic orbitals contribute roughly equally to the molecular orbital. There are several bonding interactions seen, the strongest of which is between the terminal ligand molecular orbitals. As seen on the Gaussian calculated molecular orbital, these orbitals overlap to form large sections of the same phase (area A). Additionally, strong bonding interactions are seen between the orbitals of the bridging ligands (area B), which also overlap. The MO is not as delocalised as MO 37, but still exhibits some delocalisation. Finally, there are very weak bonding interactions through space between the terminal and bridging ligand orbitals. In addition to the bonding interactions, there are some antibonding interactions between the terminal and bridging ligands. However, these are through space, so are not as strong as the bonding interactions. Overall, this molecular orbital is a bonding orbital. As before, the only nodes seen in this MO are the six lesser nodes on the atom centres.

Molecular Orbital 39 - neither bonding nor antibonding

This molecular orbital is comprised of the p-orbitals of the Cl atoms. There is a stronger contribution from the bridging Cl than the terminal Cl atoms. In this MO, there are strong bonding and antibonding interactions. There are the 4 lesser nodes expected on the Cl atom centres, and there is also a nodal plane down the centre of the molecule. Around this are strong antibonding interactions. However, there are also strong bonding interactions between the terminal and bridging ligand AOs. This can be seen by the overlap on the Gaussian calculated MO. This overlap shows a very small amount of MO delocalisation, less than in both the previous examples. Taking all of the interactions into consideration, it can be determined that this MO is neither bonding nor antibonding.

Molecular Orbital 44 - anti-bonding

This molecular orbital is comprised of the 3p orbitals on the four Cl atoms. As before, the bridging Cl orbitals contribute more than the terminal Cl orbitals. As in the previous case, there are four lesser nodes on each atomic centre (only two of these can be seen on the diagram), and a nodal plane across the centre of the molecule, as shown on the Gaussian calculated MO. Around this nodal plane there are strong antibonding interactions. Apart from these interactions, the only other interactions in this MO are the weak through space bonding interaction between the bridging and terminal ligands. Due to this, this is an overall antibonding orbital. The MO is not delocalised.

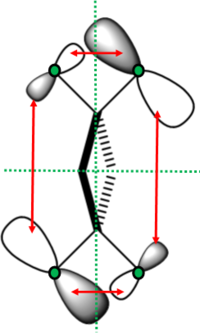

Molecular Orbital 53 - strongly antibonding

This molecular orbital is comprised of the p-orbitals on the terminal Cl (3p) and Br (4p) ligands. There is a larger contribution from the Br atomic orbitals, as this MO is closer in energy to Br than Cl. As in all the molecular orbitals examined, there are lesser nodes on the Cl and Br atomic centres. In this molecular orbital there are also two nodal planes, as shown on the diagram. The more nodes there are, the less stable the molecular orbital, and the more antibonding character it has. This can be seen in the strong antibonding interactions across the nodal planes. Additionally, in this MO there are only antibonding interactions. Due to these factors, this MO is strongly antibonding. The MO is not delocalised.

Conclusion

Over the past two weeks, the program GaussView and its potential applications have been explored. It has been used to optimise structures, predict IR, calculate molecular orbitals and charge distribution, and determine bond energies. There are many other applications of the program which have not been fully explored. As proven, computational chemistry is a very powerful tool. Through computational chemistry, it is possible to explore the properties of a compound without synthesising it, which is time-consuming and expensive. Theoretical compounds, for which there is no known synthesis, can also be explored. Additionally, extra information about molecules can be determined, which cannot be found by conventional techniques. For example, through GaussView it is possible to predict the frequency of IR peaks which cannot be seen on the spectra. However, computational chemistry has its flaws. It is only accurate to a certain degree - for example GaussView is able to determine energies only to an accuracy of 10 kJ/mol.

References

- ↑ G. Glocker, Trans. Faraday Soc., 1963, 59, 1080-1085. DOI:10.1039/TF9635901080

- ↑ S. S. Batsanov, Inorg. Mater., 2001, 37, 871-885. DOI:10.1023/A:1011625728803

- ↑ B. deB. Darwent, National Standard Reference Data Series, no. 31, National Bureau of Standards, Washington, 1970.

- ↑ O. Markovith, N. Agmon, J Phys Chem A. 2007, 111, 2253-6. DOI:10.1021/jp068960g

- ↑ L. E. Sutton (Ed.), Tables of Interatomic Distances and Configuration in Molecules & Ions, no.18, The Chemical Society, London, 1965.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 A. L. Allred, J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem., 1961, 17, 215–221. DOI:10.1016/0022-1902(61)80142-5