Rep:Mod:rs6112complab

Overview

The aims of this computational experiment are to investigate the transition state of two reactions, namely the Cope Rearrangement and the Diels-Alder reaction, and to rationalise the outcomes of the reactions using the calcaulations obtained. A transition state is the molecular geometry that lies at the maximum of the energy profile of the reaction between the reactants and the products (Technically it is a transition state. You can see it as the minimum value the maximum of the potential energy profile between reactants and products can take. João (talk) 12:36, 23 March 2015 (UTC)). The transition state geometries of the reactions are optimised using the Gaussian program, the energy values calculated allow us to draw important conclusions about the outcome of the reaction.

Though this computational experiment, different methods and basis set will be used to investigate the different reactions, and their accuracy will be compared to literature values. A more accurate basis set would contain more functions and increase the tendency to a more complete mathematical set for the calculation. While a more accurate basis set and a higher level of theory would increase the accuracy of the computations, we also need to consider the increased computational cost of running these calculations. It is therefore important to balance between the accuracy of the calculation and the computational cost required, by choosing the appropriate level of theory and basis set to be used.

The Cope Rearrangement Tutorial

Introduction

The Cope Rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene is a [3,3]-sigmatropic reaction as shown in Figure 1. [1]

Much work has been done on analysing the mechanism of this reaction, and in particular, on whether the reaction occurs via a chair or boat transition state. Maluendes and Dupius have found that the chair transition state was preferred due to it being lower in energy, [2] and this is examined computationally in this experiment.

Optimisation of Reactants and Products

HF/3-21G Level

Different conformations of 1,5-hexadiene can be obtained by rotating about the central C-C bonds in the molecule. A conformer with an antiperiplanar (app) linkage was cleaned and optimised using the Hartree-Fock method, using a 3-21G basis set. An error message was initially shown due to a pentavalent carbon in the structure, and once that was rectified, the optimisation calculation was successful. The optimised anti conformer and the summary of the results file are shown in Table 1.

| Summary Data | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

The conformer corresponded to the anti1 conformer in Appendix 1. The symmetrise function was enabled in the point group window and the symmetry of the conformer was noted as C2.

The dihedral angle of the 1,5-hexadiene molecule was changed to obtain a conformer with a gauche linkage. Optimisation was carried out with the same method. The gauche conformer was expected to have a higher energy than the anti conformation, due to the steric clash of the large groups. In the anti conformer, the two large vinyl groups are oriented 180°C from each other, and hence is expected to be lower in energy. Surprisingly, the gauche conformer obtained had a lower energy than the previously optimised anti conformer. The optimised gauche conformer and the summary of the results file are shown in Table 2.

| Summary Data | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

The higher stability of the gauche conformed was proposed by Rocque, Gonzales and Schaeffer to be due to the hydrogen bonding (An hydrogen bond with C? João (talk) 12:36, 23 March 2015 (UTC)) between the vinyl hydrogens and the pi electron clouds of the hydrocarbon chain. [3] However, some contradiction was presented in other sources of literature regarding whether the anti or gauche conformer is more stable. It is difficult to be certain that the gauche conformer is indeed more stable solely based on the computational calculation, particularly since the calculation method involved some degree of approximation. The strength of the C-H and pi bond is not particularly strong, hence it is questionable as to how much stability it can bring to the gauche conformer, and whether it is indeed enough to overcompensate for the less favourable steric interactions faced in the gauche conformer.

Furthermore, as the energies between the conformers are very similar, the Hartree-Fock method may not be sufficient to assess the lowest energy conformer accurately. The use of a more accurate method with a different basis set could be used to obtain more conclusive results about which 1,5-hexadiene conformer is the global minimum.

Summary of Optimised Conformers and Their Relative Energies

The rest of the possible conformers of 1,5-hexadiene were optimised using the HF method and 3-21G basis set. Their corresponding symmetries and energies are tabulated in the Table 3. The lowest energy conformer was identified as gauche3 using this method. However, as mentioned previously, a different conformer might possibly be identified as the lowest energy one if a different method or basis was used. The HF method neglects the effects of electron correlation, and hence might not yield the correct global minimum 1,5-hexadiene conformer.

Conversion factor: 1 Ha = 627.5 kcal/mol

| Conformer | Structure | Point Group | Energy/Hartrees HF/3-21G |

Relative Energy/kcal/mol | |||

| gauche |

|

C2 | -231.687716 | 3.103 | |||

| gauche2 |

|

C2 | -231.691670 | 0.624 | |||

| gauche3 |

|

C1 | -231.692661 | 0.000 | |||

| gauche4 |

|

C2 | -231.691530 | 0.710 | |||

| gauche5 |

|

C1 | -231.689616 | 1.911 | |||

| gauche6 |

|

C1 | -231.689160 | 2.197 | |||

| anti1 |

|

C2 | -231.692602 | 0.037 | |||

| anti2 |

|

Ci | -231.692535 | 0.079 | |||

| anti3 |

|

C2h | -231.689071 | 2.253 | |||

| anti4 |

|

C1 | -231.690971 | 1.060 |

B3LYP/6-31G* Level

The optimisation of the anti2 conformer was repeated with the DFT/B3LYP method and a 6-31G* basis set. The Density Functional Theory (DFT) is a higher level of theory that avoids some of the limitations of the HF method, while subsequently increasing the CPU time required for the calculations. The 6-31G* basis set was used in place of the 3-21G set as it was a better representation of the core orbitals through the use of 6 primitive Gaussian type orbitals (PGTO) instead of 3. (The 6-31G* basis set also has more function, including polarization functions, to describe valence orbitals. João (talk) 12:36, 23 March 2015 (UTC))

A comparsion of the geometry of the anti2 conformers optimised using the two different methods are shown in Table 4.

| Method | Structure | Energy/ Hartrees |

Bond Lengths/ Å | Bond Angles/ ° | |||

| HF/3-21G |

|

-231.692535 | C1=C4: 1.316

C4-C5: 1.509 C5-C7: 1.553 |

C1=C4-C5: 124.80

C4-C5-C7: 111.34 | |||

| B3LYP/6-31G* |

|

-234.611710 | C1=C4: 1.334

C4-C5: 1.504 C5-C7: 1.548 |

C1=C4-C5: 125.30

C4-C5-C7: 112.67 |

The B3LYP method produced a C1=C4-C5 angle that was closer to the expected value of 120° (Why do you expect 120° exactly? Is there any symmetry reason for that? Does ethene have a bond angle of 120°? Would chloro ethene have the same bond angle? João (talk) 12:36, 23 March 2015 (UTC)) and also produced a C1=C4 bond length that is closer to the literature value of 1.33 Å. It can be concluded that the B3LYP method provided a more accurate optimisation of the geometry of the 1,5-hexadiene conformer in this case. (Overall are the 2 structures significantly different? João (talk) 12:36, 23 March 2015 (UTC))

Frequency Analysis of anti2 Structure

A frequency calculation was run on the B3LYP optimised anti2 conformer to confirm that the optimised structure is a local minimum. No imaginary frequencies should be observed if the point being calculated is indeed a local minimum, as imaginary frequencies are only found if the force constant is negative. The list of vibrational frequencies obtained are shown in Figure 2.

No negative frequencies were observed, confirming that the structure was optimised to a minimum rather than a transition state maximum (What do you expect frequencies to be at a maximum of the potential energy surface? Would it be the same as a transition state? João (talk) 12:36, 23 March 2015 (UTC)). The non-zero values in the infrared column indicate that the vibrational stretch involves a change in the dipole moment of the molecule. The infrared spectrum for the anti2 conformer is shown in Figure 3.

The thermochemical parameters of the anti2 conformer were obtained from the frequency calculation. The sum of electronic and thermal energies will be used for the calculation of the activation energy of the Cope Rearrangement later on. The calculation was repeated by changing the temperature to 0.0001 K, and the the thermal contribution was observed to drop to zero. The thermochemical parameters were then equivalent to the sum of electronic and zero-point energies.

The thermochemical energy parameters are defined as below, and the values calculated are shown in Table 5.

(i) Sum of electronic and zero-point energies: Total electronic energy and zero-point vibrational energy

(ii) Sum of electronic and thermal energies: Total electronic energy and contributions from the translational, rotational, and vibrational energy modes

(iii) Sum of electronic and thermal enthalpies: Total electronic energy and correction to enthalpy due to internal energy

(iv) Sum of electronic and thermal free energies: Total electronic energy and Gibbs free energy (with entropic contribution)

| Parameter | Calculated Value (at 298.15 K)/ Hartrees | Calculated Value (at 0.0001 K)/ Hartrees |

| Sum of electronic and zero-point energies | -234.469219 | -234.469219 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal energies | -234.461869 | -234.469219 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal enthalpies | -234.460925 | -234.469219 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal free energies | -234.500809 | -234.469219 |

Optimisation of Chair and Boat Transition States

Chair TS: Berny

An allyl fragment was optimised using HF/3-21G method, and two of the optimised fragments were used to build a guess structure for the chair transition state. The terminal carbons between the two allyl fragments were set to be about 2.2 Å apart. The Hessian matrix was computed at each step in the optimisation process. The chair transition structure was obtained as shown in Table 6. The distance between the terminal carbons of the two allyl chains was observed to decrease to 2.02029 Å.

| Summary Data | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

An imaginary frequency was observed at -818 cm-1, characteristic of the Cope rearrangement. The single imaginary frequency found confirms that the optimised structure is a maximum along the reaction coordinate on the PES. If more than one imaginary frequencies were present, it would have meant that a maximum was found on the PES, but not along the reaction coordinate. The imaginary frequency corresponds to the bond breaking and bond forming vibration which occurs at the transition state. An animation of the vibration is shown in Figure 4.

Chair TS: Frozen Coordinate Method

This method requires two optimisation steps to be carried out. The structure is first optimised while the reaction coordinate is frozen, then the reaction coordinate is unfrozen and the structure is subsequently optimised to a transition state. Only the force constants along the proposed reaction coordinate are required to be calculated, hence it is an attractive method to use for larger molecules, where it may take a long time for the fully optimised Hessian matrix to be calculated.

After the first optimisation step, the distance between the terminal carbons of the two allyl fragments remained at 2.20 Å. However, after the second optimisation step, this distance was observed to decrease to 2.02061 Å, similar to the distance observed in the transition state obtained from the normal Hessian matrix method. An imaginary frequency was also observed at -818 cm-1, confirming that the structure has been optimised to a transition state.

Both the normal Hessian matix and the frozen coordinate methods produce the transition state with the same bond breaking and forming distance, hence it can be concluded that both methods are equally successful in the optimisation of the transition state.

Boat TS: QST2

The boat transition state was optimised using a quadratic synchronous transit (QST) technique. This method attempts to interpolate between the reactant and product molecules to find a maximum point on the PES. It is highly dependent on the difference between the two input structures.

The reactant and product molecules are oriented and numbered as shown in Figure 5. An optimisation using QST2 method was done, but the calculation failed to give the boat transition state as expected. The structure obtained was a chair-like structure instead. This was due to the reactant and product molecules not being structurally similar enough to the boat transition state.

For a successful QST2 calculation to be carried out, the reactants and products need to bear sufficient resemblance to the transition state. The geometries of the reactant and product molecules were hence altered as shown in Figure 6, to better resemble that the boat transition state. The dihedral angle between the central four C atoms was changed to 0°, and the =C-C-C- bond angles were changed to 100°.

The optimisation under the QST2 method was redone after altering the geometries of the reactant and product molecules. The optimisation was successful in obtaining a boat transition state, and the results are shown in Table 7.

| Summary Data | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

An imaginary frequency was observed at -840 cm-1, confirming that a transition state has been found. An animation of the vibration is shown in Figure 7.

Boat TS: QST3

An alternative method, the QST3 method, was also employed to optimise the structure of the boat transition state. The geometry of a guess transition state is used as the input for the QST3 calculation. Surprisingly, the calculation did not fail as it did for the initial calculation using the QST2 method. It successfully produced a boat transition state with similar geometry as the optimised transition state from the QST2 calculation. The presence of an imaginary frequency confirmed that a transition state has been found. The input used for the QST3 calculation is shown in Figure 8.

The total energy of the transition state found via this method is -231.60280208 Ha, while that of the transition state found via the QST2 method is -231.60280200 Ha. The extremely similar values of total energy found indicate that the transition state found is the same for both methods, and this is further confirmed by the similarity in geometry between the two optimised transition states.

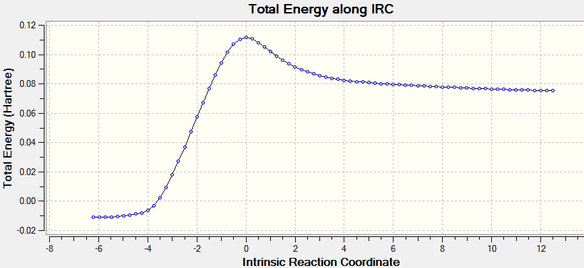

The Intrinsic Coordinate (IRC) Method

The calculations for the optimised transition states do not provide enough information as to which conformer would eventually be formed from each transition state. predict which conformer the reaction paths from the transitions structures will lead to, the minimum energy path from a transition structure down to its local minimum on a potential energy surface is followed using the Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) method. This creates a series of points by making small changes in the geometry in the direction where the gradient or slope of the energy surface is steepest. IRC calculations provide an efficient way to investigate the PES of a system.

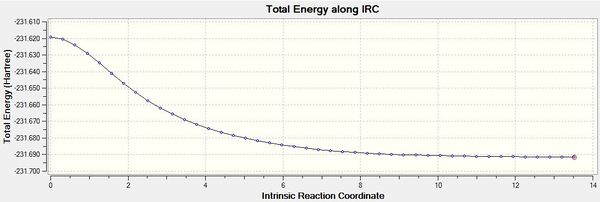

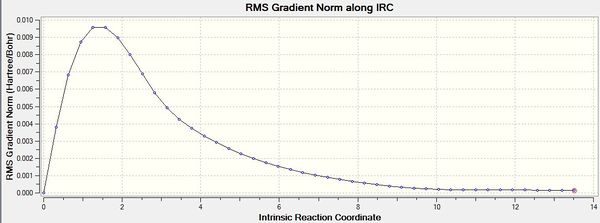

IRC calculations were carried out using the optimised chair transition states. 50 points were specified but the calculation appeared to be have converged after 44 points. The structure obtained after 44 points resembled that of a gauche 2 conformer. The results of the IRC optimisation are shown in Table 7.

| Summary | Total energy along IRC | Gradient Norm along IRC |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

While the total energy of the system has been minimised, the RMS gradient is not yet zero (If the gradient is not zero how can the energy have been minimized? Do you expect the gradient to be exactly zero? You can however adjust how close to zero you want it to be. João (talk) 17:14, 23 March 2015 (UTC)), suggesting that the optimisation is not yet complete. The structure obtained hence is likely to be not representative of the minimum geometry. A HF/3-21G optimisation on the last point of the 50-point IRC was chosen as the method to optimise the final structure. The optimisation using the HF/3-21G method yielded the gauche2 conformer with an energy comparable to that in Appendix 1. The results of the optimisation are summarised in Table 8. The RMS gradient is minimised and very close to zero, showing that the optimisation was successful.

| Summary Data | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

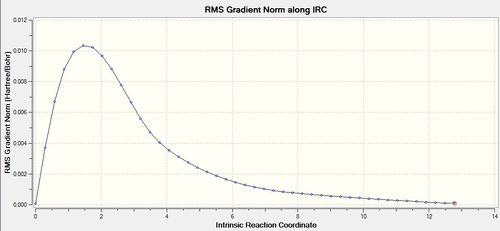

IRC calculations were then carried out on the optimised boat transition state, using the same 50-point method and reoptimisation of the final structure. The optimisation using the HF/3-21G method yielded the gauche3 conformer with an energy comparable to that in Appendix 1. The results are shown in Table 9.

| Summary | Total energy along IRC | Gradient Norm along IRC |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Activation Energies

The chair and boat transition states were reoptimised using the B3LYP/6-31G* method. An imaginary frequency was still present at the higher level of theory, indicating that a transition state was found. (By how much has the geometry changed with respect to the structure optimised at the HF/3-21G level? João (talk) 17:14, 23 March 2015 (UTC))

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic energy/ Hartree | Sum of electronic and zero-point energies/ Hartree | Sum of electronic and thermal energies/ Hartree | Electronic energy/ Hartree | Sum of electronic and zero-point energies/ Hartree | Sum of electronic and thermal energies/ Hartree | |

| at 0 K | at 298.15 K | at 0 K | at 298.15 K | |||

| Chair TS | -231.619323 | -231.466700 | -231.461341 | -234.556931 | -234.414910 | -234.408981 |

| Boat TS | -231.602802 | -231.450925 | -231.445300 | -234.543093 | -234.402340 | -234.396010 |

| Reactant (anti2) | -231.692535 | -231.539539 | -231.532566 | -234.611712 | -234.469219 | -234.461869 |

Activation energies at 298.15 K were calculated by subtracting the sum of the electronic and thermal energies for the anti2 conformer from that of the transition state (either chair or boat). Activation energies at 0 K were calculated by subtracting the sum of the elctronic and zero-point energies for the anti2 conformer from that of the transition state. The conversion factor used was as follows: 1 Hartree = 627.509 kcal/mol. A summary of activation energies calculated are shown in Table 11. The calculated values for the activation energy of the Cope rearrangement were closer to the literature when the energy values calculated from the B3LYP/6-31G* method were used. This is as expected, as the lower level Hartree-Fock method is not accurate enough to predict activation energies when compared to the higher level of theory. The B3LYP method provided us with calculated activation energies that are very close to the literature values, and hence showed that it is a very accurate and viable method for such calculations.

| HF/3-21G | HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | B3LYP/6-31G* | Experimental | |

| at 0 K | at 298.15 K | at 0 K | at 298.15 K | at 0 K | |

| ΔE (Chair)/ kcal/mol | 45.707 | 44.695 | 34.077 | 33.185 | 33.5 (± 0.5) |

| ΔE (Boat)/ kcal/mol | 55.607 | 54.764 | 41.955 | 41.324 | 44.7 (± 2.0) |

The Diels Alder Cycloaddition

Introduction

The transition states for two Diels Alder cycloaddition reactions are examined in this section. The Diels Alder reaction is [4s + 2s] cycloaddition that is predicted to occur in a concerted fashion under thermal conditions, according to the Woodward-Hoffmann rules. [4]

The following two systems are analysed and the transition states are computed to understand the selectivity observed in the Diels-Alder reaction:

1) cis-Butadiene and ethene

2) Maleic anhydride and cyclohexadiene

Reaction between cis-Butadiene and Ethene

The cycloaddition reaction between cis-Butadiene and ethene is shown in Figure 9.

Optimising Reactants: cis-Butadiene and Ethene

The cis-butadiene and ethene reactants were optimised at semi-empirical AM1 level of theory. THe AM1 level was used instead of the higher level B3LYP/6-31G* method, as the latter produced the optimised cis-butadiene as a bent structure, which would make subsequent MO analysis more complicated. As the bent structure is reported in literature to be a more accurate depiction of the molecule, for this experiment, the planar structure generated at the AM1 level will be used instead. The optimisation results are shown in Table 12.

| Reactant | Summary Data | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cis-Butadiene |

|

| |||

| Ethene |

|

|

The HOMO and LUMO of cis-butadiene and ethene are shown in Table 13 below. The HOMO of cis-butadiene is antisymmetric with respect to the plane that cuts through the central C-C bond, while its LUMO is symmetric with respect to the same plane. On the other hand, the HOMO of ethene is symmetric and its LUMO is anti-symmetric. For a successful Diels-Alder reaction to occur, the HOMO of the diene must be able to interact with the LUMO of the dienophile, and this is only possible if the two interacting orbitals are of the same symmetry. The LUMO of ethene and the HOMO of cis-butadiene are both anti-symmetric, hence the reaction is allowed.

| Reactant | HOMO | LUMO |

|---|---|---|

| cis-Butadiene |

|

|

| Ethene |

|

Optimising Transition States: The Prototype Reaction

The prototype cycloaddition transition state was created by orienting the optimised ethene molecule in the plane directly above the optimised cis-butadien molecule. The distance between the terminal carbons of the two fragments were set to 2.2 Å, and the structure was optimised using the frozen coordinate method.

The optimisation was successful in yielding a transition state, with an imaginary frequency observed at -957 cm-1. The distance between the terminal carbons of the two fragments decreased to 2.12 Å. An animation of the imaginary vibrational frequency corresponding to the bond breaking and bond forming process is shown in Table 13. From the animation of the vibration at -957 cm-1, it can be observed that the cycloaddition reaction proceeds with synchronous bond formation. In comparison, the vibration at 147 cm-1 does not show the movement of the carbon atoms which would be involved in the bond formation/bond breaking process.

| Jmol | Vibration at -957 cm-1 | Vibration at 147 cm-1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

The typical sp3C-sp3C bond length is 1.54 Å, while the typical sp2C-sp2C bond length is 1.33 Å. The van der Waals radius of the carbon atom is 1.70 Å. The C-C bond length of the partly formed σ C-C bonds in the optimised transition state is 2.12 Å, less than twice of the van der Waals radius for the carbon atom. This suggests that the carbon atoms within the partly formed σ bonds feel an attraction towards each other, and this favours the bond formation in the cycloaddition reaction. The distance is too large compared to that of a typical sp3C-sp3C bond length, so the bond is not yet fully formed, as would be expected in a transition state. The C=C bond lengths in the cis-butadiene and ethene are 1.38 Å, longer than expected for sp2C-sp2C bonds, suggesting that these bonds only have partial double bond character, and that the double bonds are in the process of being broken in the cycloaddition reaction. The C-C bond length in the cis-butadiene is 1.40 Å, shorter than expected for a sp3C-sp3C bond, suggesting that the bond is beginning to get some partial double bond character.

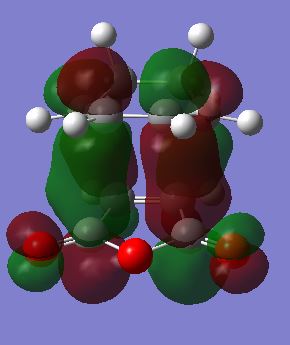

The HOMO and LUMO for the optimised transition state are visualised as shown in Table 14.

| HOMO | LUMO |

|---|---|

|

The Woodward-Hoffmann Rules can be used to predict if a particular pericyclic reaction is allowed, based on considerations of conservation of orbital symmetry between the reactants and products. [4] The reaction studied here is a thermal 4n +2 cycloaddition that proceeds in a suprafacial manner. Forming two new sigma C-C bonds between ethene and cis-butadiene would require the two interacting orbitals to be of the same symmetry and of appropriate phases for interaction.

Comparing the MOs obtained from the transition state to that of the reactants, the HOMO of the transition state is anti-symmetric, bearing some resemblance to the HOMO of cis-butadiene and the LUMO of ethene. This is as expected, as the ethene acts as he dienophile in this reaction, so its LUMO overlaps with the HOMO of the electron rich diene. As the two interacting orbitals have the same antisymmetric symmetry, they can overlap in the allowed reaction to form a transition state with a HOMO that is also antisymmetric. The LUMO of the transition state is formed from the overlap of the HOMO of ethene and LUMO of cis-butadiene, hence it is symmetric. As the interacting orbitals are of same symmetry, as discussed above, the cycloaddition reaction is Woodward-Hoffmann allowed.

IRC Analysis

An IRC calculation was run in both directions. The results of the calculation are shown in Table 15. The animation shows the formation of the expected product, confirming that the optimised transition state is correct. The total energy shows the pathway that the system of reactants takes, through a high energy transition state, to the cycloaddition product.

| Animation | Total Energy Along IRC |

|---|---|

|

Activation Energies

The energy values used for calculating the activation energy of the reaction is tabulated in Table 16.

| Semi-empirical AM1 | B3LYP/6-31G* | |

|---|---|---|

| Sum of electronic and thermal energies at 298.15 K/ Hartree | Sum of electronic and thermal energies at 298.15 K/ Hartree | |

| cis-Butadiene | 0.13857 | -155.90649 |

| Ethene | 0.08025 | -78.53319 |

| Transition State | 0.25945 | -234.41309 |

The activation energy for the reaction was calculated to be 24.07 kcal/ mol and 16.69 kcal/ mol using energy values calculated at the AM1 and B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory respectively (For the DFT value, did you consider the planar of twisted butadiene as the stable reactant? Did you reoptimise the transition state or did you take the AM1 optimised structure? João (talk) 17:14, 23 March 2015 (UTC)). The literature values for this reaction is reported to be 27.5 kcal/ mol. It is surprising that while semi-empirical AM1 is a lower level of theory than B3LYP/6-31G*, the calculated activation energy is closer to the literature value. This could be due to the semi-empirical AM1 being parameterised against experimental data, producing energy calculations that provide a better match with experimental values.

Reaction between Maleic Anhydride and Cyclohexa-1,3-diene

The reaction of maleic anhydride and cyclohexa-1,3-diene is a thermally allowed, suprafacial process according to Woodward-Hoffmann rules. The reaction proceeds as shown in Figure 10 to give two stereochemically distinct adducts, either the exo- or endo- one. The exo- adduct is the thermodynamic product, as it avoids the steric clashes present in the endo- adduct and is energetically more stable. The endo- adduct is the kinetic product and it is reported in literature to be the favoured product (Under which conditions would it be the favoured product? João (talk) 17:14, 23 March 2015 (UTC)) due to stabilisation of the endo- transition state by secondary orbital interactions. [5] According to extended Huckel calculations performed on the transition state geometries by Woodward and Hoffman, the secondary orbital interactions arise from the overlap of orbitals that are not directly involved in bond formation and contribute to lowering the energy of the endo- transition state.

The selectivity of this reaction is examined by studying the transition states that lead to the two respective adducts.

Optimising Reactants: Maleic Anhydride and Cyclohexa-1,3-diene

The reactants were optimised at the semi-empirical AM1 level of theory. The results are shown in Table 17 below.

| Reactant | Summary Data | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclohexa-1,3-diene |

|

| |||

| Maleic Anhydride |

|

|

Optimising Transition States: Endo- and Exo-

The endo- and exo- transition states were generated and optimised using the frozen coordinate method at the semi-empirical AM1 level of theory. The results are shown in Table 18 below. The endo- transition state is lower in energy as compared to the exo- transition state. It is as expected, according to Woodward-Hoffmann, due to the presence of stabilising secondary orbital interactions. As the endo- transition state is lower in energy, the endo- adduct is formed as the kinetic product.

| Transition State | Total Energy/ Hartrees | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endo- | -0.05150437 |

| |||

| Exo- | -0.05041814 |

|

Imaginary frequencies were observed at -807 cm-1 and -811 cm-1 for the endo- and exo- transition states. This confirms that a transition state has been successfully found, instead of a minimum. The vibrations corresponding to the imaginary frequencies are shown in Table 19. The imaginary frequency vibration along the reactive bond forming the transition state shows that the reaction occurs in a concerted synchronous manner.

| Transition State | Imaginary Frequency | Lowest Positive Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Endo- |

|

|

| Exo- |

|

(Although your Exo strcutures above seem to have the expected Cs symmetry, they seem distorted in the frequency animation and the

MO Analysis of Endo- and Exo- Transition States

The molecular orbitals of the optimised endo- and exo- transition states are shown in Table 20.

| Transition State | HOMO | LUMO | LUMO+1 | LUMO+2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endo- |

|

|

|

|

| Exo- |

|

|

|

|

The secondary orbital interaction that stabilises the endo- transition state is predicted to be between the carbonyl groups and the double bond on the cyclohexa-1,3-diene. It is expected to be present in the HOMO of the transition state. However, this was not observed as above in the HOMO of the endo- transition state. There is no in-phase overlap between the orbitals on the carbonyl groups and those on the double bond on cyclohexa-1,3-diene. The search for the secondary orbital interaction was carried out by visualising the molecular orbitals from HOMO-3 to LUMO+3. Out of these, only LUMO+1 and LUMO+2 showed the secondary orbital interactions, and they are also shown in Table 20. The p orbitals of the carbonyl carbon in the maleic anhydride overlap in phase with the p orbitals of the double bond in cyclohexa-1,3-diene. However, the LUMO+1 and LUMO+2 do not contribute to bonding, hence the secondary orbital interactions in these MOs would not contribute to lowering the energy of the transition state as expected. It should also be noted that no secondary orbital interactions are observed in any of the MOs from HOMO-3 to LUMO+3 for the exo- transition state. A possible explanation for the LUMO+1 and LUMO+2 of the endo- transition state showing the secondary orbital interactions instead of the HOMO is that the energy levels of the MOs may be quite close (Is that the case in your calculation? João (talk) 17:14, 23 March 2015 (UTC)), and the order of the MOs may change slightly if mixing of the orbitals occurred upon combining the reactants. The low level of theory used here for the calculations could also be a possible reason for deviation from what is reported in the literature.

IRC Analysis

The results of the IRC calculations from the endo- and exo- transition states are shown in Table 21.

| Transition State | Energy/ Hartrees | RMS Gradient | Total Energy Along IRC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endo- | -0.1599909 | 0.0000258 |

|

| Exo- | -0.16017060 | 0.0000390 |

|

As expected, the exo- adduct is more energetically stable than the endo- adduct by 0.113 kcal/ mol. This is consistent with reported literature that the exo- adduct is the thermodynamic product and the endo- adduct is the kinetic product. The activation energies of the endo- and exo- transition states are calculated to be 28.14 kcal/ mol and 28.90 kcal/mol respectively, using values obtained at the semi-empirical AM1 level of theory. The calculated values differ quite significantly from the experimental value of 11.4 kcal/ mol, and could possibly be attributed to the low level of theory used for the calculations. However, the calculated values do illustrate that the activation energy is higher for the exo- transition state, supporting the analysis that the exo- product is the thermodynamic product.

(Could steric effects play a role in the energetics of the transition state? João (talk) 17:14, 23 March 2015 (UTC))

Limitations of the AM1 Method

The AM1 method used in the calculations above do suffer from some limitations, in terms of factors that it neglects. Its key limitations include What references did you use to make these statements? João (talk) 17:14, 23 March 2015 (UTC)):

- Overestimation of the stability of the alkyl group

- Underestimation of the rotational barriers for bonds with partial double bond character

- Correct prediction of hydrogen bond strengths but often with the wrong geometry

- Poor prediction of van der Waals interactions

It is plausible that the limitations of the AM1 method led to the absence of the expected secondary orbital interactions in the HOMO of the endo- transition state. A higher level of theory and higher basis set could be used in an attempt to improve the results. However, as suggested in literature [6], it could also be possible that secondary orbital interactions are not responsible for the preference of the endo- transition state, and that van der Waals forces instead are responsible for the observed difference in energies.

Conclusion

The transition states of the Cope Rearrangement and the Diels-Alder reaction were characterised using the Gaussian program. Various levels of theory were used, with the higher level B3LYP/6-31G* being generally more accurate than the two levels of theory used. Presence of imaginary frequencies confirmed that transition states were found for the two reactions, and animations of the vibrations were used to illustrate the formation of the transition structures. While the secondary orbital interaction was not found in the endo- transition state for the Diels-Alder reaction, the calculations nevertheless showed that the endo- adduct was the kinetic product of the reaction and had a lower activation barrier. The absence of the secondary orbital interaction was attributed to the low level of theory used.

References

- ↑ A. C. Cope and E. M. Hardy., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1940, 62, 441.

- ↑ S. A. Maluendes and M. Dupuis, J. Chem. Phys. 1990, 93, 8, 5902-5911.

- ↑ B. G. Rocque, J. M. Gonzales and H. F. Schaeffer, Mol. Phys. 100(4), 2002, 441-446.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 R. B. Woodward and R. Hoffmann, Angew. Chem. 1969, 8, 781.

- ↑ J. J. Vollmer and K. L. Servis, J. Chem. Edu. 1970, 47, 7, 491-500.

- ↑ W> C. Herndon and L. H. Hall, Tetrahedron Lett. 1967, 3095.