Rep:Mod:quintinlo00690346

Experiment 1C: Advanced Molecular Modelling and assigning the absolute configuration of an epoxide

Introduction

Computational techniques such as molecular modelling are often used to analyse various properties of organic compounds and reactions. Properties such as regioselectivity, geometry and NMR data of several organic compounds such as taxol, cyclopentadiene dimers and epoxides were investigated using such techniques in this experiment, which would be useful when the actual synthetic experiment is carried out in the laboratory.

The Hydrogenation of a Cyclopentadiene Dimer

Exo Dimer 1 and Endo Dimer 2 were defined and optimised in ChemBio3D Ultra 13.0 using the MMFF94 force-field option, these force-field calculations reflect the thermodynamic stability of both dimers. The following energies for the exo and endo dimers were obtained:

- Exo Dimer 1: 55.3785 kcal mol-1

- Endo Dimer 2: 58.1926 kcal mol -1

The dimerisation of cyclopentadiene is endo selective even though calculations have shown that the endo dimer is higher in energy than the exo dimer. This shows that the exo dimer is the thermodynamic product while the endo dimer is the kinetic product which is due to the fact that the exo dimer is more strained as compared to the endo dimer. The endo transition state is preferred due to favourable secondary orbital overlap[1] which is not present in the exo transition state. The dimerisation is not reversible because a reversible reaction will lead to the formation of the more thermodynamically stable exo product.

The hydrogenation of the endo dimer was then analysed using ChemBio3D Ultra 13.0 using the MM2 option. Hydrogenation leads to the formation of compounds 3 and 4 and the results obtained are illustrated in table 1 below.

| Properties | Compound 3 (kcal mol-1) | Compound 4 (kcal mol-1) |

|---|---|---|

| Stretching | 1.2777 | 1.0965 |

| Bending | 19.8585 | 14.5243 |

| Stretch-Bend | -0.8345 | -0.5494 |

| Torsion | 10.8110 | 12.4974 |

| Non-1,4 van der Waals | -1.226 | -1.0700 |

| 1,4 van der Waals | 5.6328 | 4.5126 |

| Dipole/Dipole | 0.1621 | 0.1406 |

| Total Energy | 35.6850 | 31.1520 |

The observed reactivity of the cyclopentadiene dimer towards hydrogenation is due to thermodynamic effects, as shown from the data above, where hydrogenation of the dimer leads to formation of the lower energy and more thermodynamically stable compound 4 before forming the tetrahydro derivative which was observed in literature[2],[3]. The rate of hydrogenation of the double bond in the norbornene ring occurs at least 5 times faster[2] as compared to the other double bond in the cyclopentene ring. It was reported that the heat of hydrogenation[4] of the double bond in the norbornene ring was 32.2 kcal mol-1, while the heat of hydrogenation of the double bond in the cyclopentene ring was 26.2 kcal mol-1, which supports the conclusion made above.

The relative contributions of stretching, stretch-bend, torsion, van der Waals and dipole/dipole to the total energy are similar for both compounds 3 and 4, where the major contributions to the total energy for both compounds are bending and torsion. The difference in the total energy or the difference in the thermodynamic stability of compounds 3 and 4 is due to the difference in bending contribution to the total energy between both compounds. The bending contribution is greater in compound 3 as compared to 4 and this could be attributed to the presence of a double bond in the norbornene ring in compound 3. Bending of compound 3 will lead to steric repulsion[5] between the pi-orbitals of the double bond and the occupied orbitals of the methylene bridge whereas compound 4 does not have this problem as the double bond is located in the cyclopentene ring and is further away from the methylene bridge.

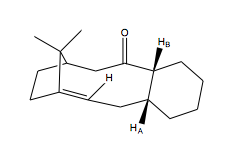

The most stable isomer of Taxol 9 as shown above was determined using the MMFF94 force-field option. 4 different conformations of 9 were generated as shown in the table below. They are conformations 9-1, 9-2, 9-3 and 9-4.

| Conformation | Energy (kcal mol-1) | Additional Comments |

|---|---|---|

| 9-1 | 70.5635 | Cyclohexane ring is in a chair conformation where HA and HB are pointing upwards. |

| 9-2 | 77.9116 | Cyclohexane ring is in a boat conformation where HA and HB are pointing upwards. |

| 9-3 | 63.2701 | Cyclohexane ring is in a chair conformation where HA and HB are pointing downwards. |

| 9-4 | 67.8014 | Cyclohexane ring is not in a twist-boat conformation where HA and HB are pointing downwards. |

Taxol 10, shown in diagram 3, is more thermodynamically unstable relative to Taxol 9. The energies of different conformations of taxol 10 (10-1, 10-2, 10-3, 10-4) were obtained through MMFF94 force-field calculations, where the conformation of the cyclohexane ring and the configuration of the bridgehead olefin were kept constant.

| Conformation | Energy (kcal mol-1) | Additional Comments |

|---|---|---|

| 10-1 | 60.5744 | Cyclohexane ring is in a chair conformation where HA and HB are pointing upwards. |

| 10-2 | 66.2997 | Cyclohexane ring is in a boat conformation where HA and HB are pointing upwards. |

| 10-3 | - | Cyclohexane ring is in a chair conformation where HA and HB are pointing downwards could not be obtained in the Chembio3D Ultra 13.0 program. |

| 10-4 | 74.3915 | Cyclohexane ring is not in a twist-boat conformation where HA and HB are pointing downwards. |

The most stable conformation of Taxol is Taxol 10-1, which has the lowest energy as shown in the table above. The cyclohexane ring in Taxol is locked and is not able to undergo ring-flipping as it is bonded to another ring structure, when the cyclohexane ring is in a chair conformation, the C-H bonds in the ring are perfectly staggered, thus eliminating torsional strain. The twist boat and boat conformations of the cyclohexane ring are unstable relative to the chair conformation due to the presence of eclipsed C-H bonds in the ring where this eclipsed interaction[6],[7] is slightly relieved in the twist-boat conformation[7], which results in the stabilisation of the twist-boat conformation over the boat conformation.

The difference in energies between the conformations of taxol shown in tables 2 and 3 above are due to several factors. The difference in energy between the conformations of Taxol 9 and 10 are similar due to the difference in energies between the chair, twist-boat and boat conformations of cyclohexane reported in literature[6],[7], deviation from literature values could be due to steric clashes between the carbonyl oxygen and HB when both atoms are pointing upwards in Taxol 9-2. However the opposite is true in Taxol 10, where steric clashes between the carbonyl oxygen and HB occur when both atoms are pointing downwards leading to an increase in energy as shown in conformation 10-4. These steric clashes were avoided when HB was pointing in the opposite direction relative to the carbonyl oxygen.

In both Taxol 9, it was found through further minimisations using the MMFF94 force-field that when the HA and HB are trans relative to each other with the cyclohexane ring is in a chair conformation where HB points downwards and HA points upwards, an energy of 60.6326 kcal mol-1 was obtained, which was significantly lower than the energies obtained in table 2 above. For Taxol 10, where HA and HB are trans relative to each other with the cyclohexane ring is in a chair conformation where HB points upwards and HA points downwards, giving an energy of 61.2132 kcal mol-1, which is similar to the energy of conformation 10-1.

Taxol 9 and 10 violates Brendt's rule, double bonds to bridgehead carbons are favoured in this case due to the presence of a large 9-membered ring. It was reported in literature[8] that bridgehead olefins are strained, which is quantified by the term olefinic strain (OS), and it follows different conformational rules as compared to other ring systems. The bridgehead olefin in Taxol adopts a trans configuration because the larger 9-membered ring structure adapts its geometry to give a more stable 5-membered ring[8], which in this case has an envelope conformation. Taxol 9 and 10 contains a 'hyperstable' olefin, which has a negative value of OS and is more stable than the parent hydrocarbon, hence the rate of functionalisation of the alkene is very slow. This enhanced stability of the olefin in Taxol 9 and 10 are due to two reasons, one being the extra stability afforded to the alkene by the cage structure and the other being the inherent instability of the parent hydrocarbon[8] caused by the presence of torsional strain.

Correlation between the reactivity of the bridgehead olefin in Taxol 9 and 10 and the olefinic strain (OS) could be explained using the frontier molecular orbital theory. OS reflects the twisting strain of the C=C double bond and a large value of OS indicates a highly twisted alkene which results in reduced overlap of pi-orbitals, leading to an increase in energy of the HOMO and a decrease in energy of the LUMO, giving a smaller HOMO-LUMO gap. A negative value of OS in Taxol 9 and 10 indicates a strong overlap of pi-orbitals in the C=C double bond which leads to a large HOMO-LUMO gap and a slow rate of functionalisation.

Intermediate 18 was optimised using the MMFF94 force-field option in ChemBio3D Ultra 13.0 and Avogadro, where the NMR spectra of the intermediate was generated using a high performance computer (HPC). Results were published on D Space[9]. Deuterated benzene was used as the solvent for both 13C NMR and 1H spectra and it was compared with the values reported in literature[10] in tables 4 and 5 respectively below. The 1H NMR spectrum reported in literature[10] was found to be partially assigned when compared to the simulated spectrum in diagram 6 below, hence only the chemical shifts of key protons in intermediate 8 were compared with the chemical shifts reported in literature[10].

The energy obtained for intermediate 18 after minimisation was 100.442 kcal mol-1.

| Chemical shift reported in literature8 (ppm) | Chemical shift simulated using HPC (ppm) |

|---|---|

| 211.49 | 211.93 |

| 148.72 | 147.87 |

| 120.90 | 120.13 |

| 74.61 | 92.84 |

| 60.53 | 65.94 |

| 51.30 | 54.93 |

| 50.94 | 54.76 |

| 45.53 | 49.53 |

| 43.28 | 48.04 |

| 40.82 | 45.65 |

| 38.73 | 44.01 |

| 36.78 | 41.47 |

| 35.47 | 38.51 |

| 30.84 | 33.70 |

| 30.00 | 32.47 |

| 25.56 | 28.36 |

| 25.35 | 26.50 |

| 22.21 | 24.45 |

| 21.39 | 24.01 |

| 19.83 | 22.59 |

| Chemical shift reported in literature8 (ppm) | Chemical shift simulated using HPC (ppm) | Additional Comments |

|---|---|---|

| 5.21 (1H) | 5.97 (1H) | This chemical shift corresponds to the proton on bridgehead olefin. |

| 2.70-3.00 (6H) | 2.78 (2H) | The CH2 group adjacent to the carbonyl in intermediate 18 is in two different environments. This proton corresponds to the proton pointing in the opposite direction of the carbonyl group. |

| 1.10 (3H) | 1.58 (3H) | This proton corresponds to the other proton adjacent to the carbonyl, which points away from the ring system. |

In the simulated 13C NMR spectrum, it was observed that the chemical shifts reported in literature[10] were increasingly inaccurate as we move upfield. The chemical shift reported in literature[10] at 74.61 ppm corresponds to the chemical shift at 92.84 ppm in the simulated spectrum, this could be rationalised by the fact that carbon atoms bonded to heavy elements such as sulfur in intermediate 8 requires correction for spin-orbit coupling errors in the simulated spectrum.

The protons chosen for comparison purposes in table 5 are protons that are well defined in terms of their values of chemical shift, protons such as those bonded to a bridgehead olefin and protons that are adjacent to a carbonyl group. In general, the assigned chemical shifts in literature[10] show little correlation with the assigned chemical shifts in the simulated spectrum. The observed difference in chemical shift values between those reported in literature[10] and the ones generated through simulation could be explained by the fact that the literature values[10] were published over 20 years ago, where NMR analysis were not as powerful and reliable as compared to the computer simulations available today. It was noted that the chemical shifts reported in literature[10] does not specify which chemical shift corresponds to which carbon or proton environment, hence comparisons made above are rough approximations.

The free energy ΔG of intermediate 17[11] and 18 were obtained using the HPC via the Gaussian extension in Avogadro. The results are reported below:

- Intermediate 17: -4335904.5800 kJ mol-1

- Intermediate 18: -4335914.1789 kJ mol-1

The difference between the free energies of intermediates 17 and 18 is approximately equal to 10 kJ mol-1, giving an equilibrium constant of 0.01766. Therefore the equilibrium lies towards 18 (shown in diagram 4) which was expected as intermediate 18 is more thermodynamically stable (100.442 kcal mol-1) than intermediate 17 (104.444 kcal mol-1).

Analysis of the properties of the synthesised alkene epoxides

Crystal structure of the Shi asymmetric Fructose catalyst

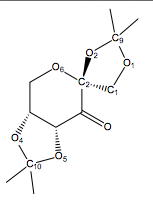

The C-O bond lengths in the Shi Catalyst were analysed using the Mercury program after a thorough search through the Cambridge crystal database (CCDC) via the Conquest program. The results obtained are shown in table 6 below.

| Bond | Bond Length (Angstroms) |

|---|---|

| C2-O2 | 1.423 |

| C2-O6 | 1.415 |

| C9-O1 | 1.423 |

| C9-O2 | 1.454 |

| C1-O1 | 1.429 |

| C10-O4 | 1.456 |

| C10-O5 | 1.428 |

Due to the anomeric effect (illustrated in diagram 9), the length of the C2-O2 bond was expected to be longer than the C1-O1 bond, where the lone pair of oxygen in O6 is antiperiplanar with the C2-O2 σ* anti-bonding orbital which means the lone pair of electrons on O6 will occupy the C2-O2 σ* anti-bonding orbital, lengthening the C2-O2 bond in the process. However this did not occur in the Shi catalyst (diagram 7), where both lone pair of electrons on O6 are not anti-periplanar with the C2-02 σ* anti-bonding orbital, hence we can conclude that no anomeric effect is present.

However, this anomeric effect was observed in the O2-C9-O1 centre, where the lone pair of electrons on O1 is anti-periplanar with the C9-O2 bond, hence the C9-O2 bond length is longer as compared to the other C-O bond lengths in the 5-membered ring structure in the catalyst. This anomeric effect was observed to be present in the O4-C10-O5 centre, where the O4-C10 bond is longer than the O5-C10 bond.

The difference in the C2-O6 and C2-O2 bond lengths is due to the fact that these two bonds are located in a 6-membered ring and a 5-membered ring respectively in the Shi Catalyst.

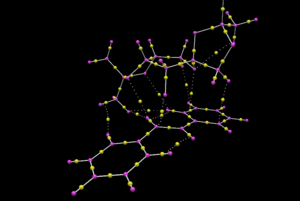

Crystal structure of the Jacobsen asymmetric pre-catalyst

The close approach between the t-butyl groups on the rings of the Jacobsen catalyst were analysed using the Mercury program. It was observed[13] that the presence of t-butyl group on the aromatic rings helped to increase the selectivity of the catalyst, where epoxidation of cis alkenes are favoured. The steric bulk associated with the phenyl rings in the Jacobsen catalyst prevents the alkene from approaching the Manganese centre from either the left or the right side (a and b in diagram 12), while the cyclohexane ring makes approach by the alkene from the syn side unfavourable. The closest distance between the two t-butyl groups was found to be 3.40 angstroms (highlighted by the light blue line between two carbon atoms in diagram 11) which is approximately twice the van der Waals radii for carbon (1.70 Angstroms). Maximum attraction occurs when the distance between the two carbon atoms in the t-butyl groups are twice the van der Waals radii of carbon, which applies in this case for the Jacobsen catalyst, therefore it was concluded that the attractive interactions between these two t-butyl group blocks the alkene from approaching via trajectory c in diagram 12. Thus the alkene approaches from the top face of the catalyst (d in diagram 12), selectively forming a cis epoxide.

Calculated NMR properties of R/S Styrene oxide and Trans/cis beta-methylstrene oxide

The structures of R-Styrene oxide, S-Styrene oxide, Trans beta-methylstyrene oxide and Cis beta-methylstyrene oxide was first optimised using the MMFF94 force-field option in ChemBio3D Ultra 13.0, where the energy of both epoxides are shown below.

- R-Styrene oxide: 21.6622 kcal mol-1

- S-Styrene Oxide: 21.6327 kcal mol-1

- Trans beta-methylstyrene oxide: 23.1307 kcal mol-1

- Cis beta-methylstyrene oxide: 23.9356 kcal mol-1

The 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra for both R/S Styrene oxide and Trans/cis beta-methylstyrene oxide were simulated using the HPC, similar to the method used for intermediate 8 above. The chemical shifts of the simulated spectra were compared to those reported in literature[14],[15],[16],[17]. Full results were published on D Space[18],[19],[20],[21].

| Chemical shift reported in literature[14] (ppm) | Chemical shift simulated using HPC (ppm) |

|---|---|

| 137.63 | 135.14 |

| 128.52 | 124.13 |

| 128.20 | 123.42 |

| 125.53 | 122.95 |

| 52.20 | 54.06 |

| 51.31 | 53.46 |

| Chemical shift reported in literature[14] (ppm) | Chemical shift simulated using HPC (ppm) |

|---|---|

| 137.63 | 135.03 |

| 128.52 | 124.03 |

| 128.20 | 123.31 |

| 125.53 | 122.85 |

| 52.20 | 53.95 |

| 51.31 | 53.36 |

| Chemical shift reported in literature[14] (ppm) | Chemical shift simulated using HPC (ppm) |

|---|---|

| 7.24-7.35 (5H) | 7.30-7.51 (5H) |

| 3.83 (1H) | 3.66 (1H) |

| 3.11 (1H) | 3.11 (1H) |

| 2.76 (1H) | 2.53 (1H) |

| Chemical shift reported in literature[15] (ppm) | Chemical shift simulated using HPC (ppm) |

|---|---|

| 7.26-7.38 (5H) | 7.30-7.52 (5H) |

| 3.85-3.88 (1H) | 3.67 (1H) |

| 3.14-3.16 (1H) | 3.12 (1H) |

| 2.79-2.82 (1H) | 2.54 (1H) |

| Chemical shift reported in literature[16] (ppm) | Chemical shift simulated using HPC (ppm) |

|---|---|

| 137.9 | 134.98 |

| 128.6 | 124.01 |

| 128.2 | 123.30 |

| 125.7 | 122.80 |

| 59.7 | 62.36 |

| 59.2 | 60.58 |

| 18.1 | 18.83 |

| Chemical shift reported in literature[17] (ppm) | Chemical shift simulated using HPC (ppm) |

|---|---|

| 135.5 | 132.71 |

| 127.9 | 123.30 |

| 127.4 | 122.61 |

| 126.5 | 122.34 |

| 57.5 | 58.89 |

| 55.0 | 57.56 |

| 12.5 | 12.97 |

| Chemical shift reported in literature[16] (ppm) | Chemical shift simulated using HPC (ppm) |

|---|---|

| 7.20-7.40 (5H) | 7.30-7.50 (5H) |

| 3.57 (1H) | 3.41 (1H) |

| 3.03 (1H) | 2.78 (1H) |

| 1.45 (3H) | 0.72 (1H), 1.59 (1H), 1.68 (1H) |

| Chemical shift reported in literature[17] (ppm) | Chemical shift simulated using HPC (ppm) |

|---|---|

| 7.29 (5H) | 7.40-7.55 (5H) |

| 4.05 (1H) | 3.99 (1H) |

| 3.33 (1H) | 3.29 (1H) |

| 1.08 (3H) | 0.70 (1H), 0.84 (1H), 1.44 (1H) |

In general, the chemical shifts reported in literature[14],[15] corresponds to the chemical shifts simulated by the HPC for both R/S Styrene oxides and there was very few differences between the 13C and 1H NMR spectra. However, missing peaks were observed in literature[14],[15] for 13C NMR of both R/S Styrene oxides (118.27 and 118.17 ppm respectively) when compared to the simulated13C NMR spectra, which means that the reported chemical shifts in literature[14] might not be accurate.

The chemical shifts reported for trans/cis beta-methylstyrene oxides in literature[16],[17] was observed to correlate well with the simulated chemical shifts. It was observed that the literature[16],[17] contained missing peaks in the 13C NMR spectra of both trans/cis beta-methylstyrene oxides (118.49, 121.26 ppm respectively) when compared to the simulated 13C NMR spectra. It was concluded that the methyl group adjacent to the epoxide is located in different carbon environments in trans and cis beta-methylstyrene oxides, where the chemical shift for this methyl group in13C NMR was reported to be in the region of 18 ppm for trans beta-methylstyrene oxide and in the region of 12 ppm for cis beta-methylstyrene oxide. This is because in cis beta-methylstyrene oxide, the methyl group is closer to the phenyl ring as compared to the methyl group in trans beta-methylstyrene oxide, hence the methyl group in cis beta-methylstyrene oxide is more shielded by the phenyl ring, leading to a lower chemical shift. In 1H NMR of both trans/cis beta-methylstyrene oxides, it was reported in literature[16],[17] that the 3 protons in the methyl group adjacent to the epoxide are in the same proton environment (table 13 and 14), however, this proved to be untrue as the simulated 1H NMR spectra of trans/cis beta-methylstyrene oxides showed that the 3 protons are in 3 different proton environments (table 13 and 14).

It was noted that the literature did not specify which carbon or proton environment corresponds to which chemical shift, thus making comparisons between literature and simulated values difficult.

Calculated chiroptical properties of the product

The optical rotation of R/S styrene oxide and (R, R) Trans/ (R, S) cis beta-methylstyrene oxide were calculated using the HPC and the results obtained are shown below. Results were published on D Space[22],[23],[24],[25],[26],[27],[28],[29].

For R-styrene oxide, the calculated values for optical rotation are -30.49 o at 589 nm and -95.26 o at 365 nm when chloroform was used as the solvent. It was reported in literature[30] that the optical rotation of R-styrene oxide at 589 nm is -24 o in chloroform at 21 oC. No literature value was found for the optical rotation at 365 nm.

The optical rotation for S-styrene oxide was calculated and an optical rotation of 30.27 o at 589 nm and 94.51 o at 365 nm was obtained when chloroform was used as the solvent. This closely matches the values reported in literature[31] where an optical rotation of 32.1 o was obtained at a wavelength of 589 nm at 25oC in the presence of chloroform. No literature value was found for optical rotation at 365 nm.

For (R, R) trans beta-methylstyrene oxide, an optical rotation of 46.83 o at 589 nm and 137.88 o at 365 nm was obtained when chloroform was used as a solvent. This was similar to the value reported in literature[32] where (R,R) trans beta-methylstyrene oxide has an optical rotation of 40.8 o at 589 nm at 25oC in the presence of chloroform. No literature value was found for the optical rotation at 365 nm.

For (R,S) cis beta-methylstyrene oxide, an optical rotation of -37.43 o at 586 nm and -144.67 o at 365nm was obtained when chloroform was used as a solvent. This closely matches the value reported in literature[33] where an optical rotation of -37.8 o was reported for (R,S) cis beta-methylstyrene oxide at 586 nm at 25 oC in the presence of chloroform. Literature value for the optical rotation at 365 nm is unavailable.

It was observed that the value of the optical rotation varies with the solvent, temperature and the concentration of the epoxide. A wide range of values were reported in various journals at different wavelengths and it is widely known that the values of optical rotation varies with different experiments. Hence comparisons made between literature values and calculated values are not ideal.

Using the calculated properties of transition state for the reaction involving beta-methylstyrene

Shi Catalyst

The sum of electronic and thermal free energies of the epoxidation of trans beta-methylstyrene were provided and is shown in table 15 below.

| Transition State | Total Free Energy (Hartree) | Total Free Energy (kJ mol-1) |

|---|---|---|

| R,R 1 | -1343.022970 | -3526107.0763 |

| R,R 2 | -1343.019233 | -3526097.2648 |

| R,R 3 | -1343.029272 | -3526123.6222 |

| R,R 4 | -1343.032443 | -3526131.9477 |

| S,S 1 | -1343.017942 | -3526093.8753 |

| S,S 2 | -1343.015603 | -3526087.7343 |

| S,S 3 | -1343.023766 | -3526109.1662 |

| S,S 4 | -1343.024742 | -3526111.7287 |

The two transition states with the lowest free energy are R,R 2 and S,S 2 as shown in table 15 above. The difference in free energy between these two transition states (ΔG) is 9.5305 kJ mol-1.

The difference in energy was then converted to an equilibrium constant (K) using the equation ΔG=-RTInK. Where K = 0.02135. The enantiomeric excess (ee) was then worked out from the equilibrium constant using the following formula: ee = (1-K)/(1+K) where an enantiomeric excess of 95.8 % was obtained. This value is slightly higher than the one reported in literature[16] (92.0 %), which highlights the selectivity of the epoxidation reaction using the Shi Catalyst.

The R,R 2 transition state shows that epoxidation occurs on the Si,Re face of the alkene, where the carbon atom bonded to the phenyl ring in the alkene is the Si face while the carbon atom bonded to the methyl group is the Re face of the alkene, it also showed that the axial dioxirane oxygen was used for the transfer of oxygen to the alkene and that the phenyl group of the alkene was oriented in such a way that it was exo relative to the fructose in the Shi Catalyst.

The S,S 2 transition state shows that epoxidation occurs on the Re,Si face of the alkene, where the carbon atom bonded to the methyl group is the Si face of the alkene while the carbon atom bonded to the phenyl ring is the Re face of the alkene. The alkene selectively attacks the axial dioxirane oxygen atom where the phenyl ring on trans beta-methylstyrene is exo with respect to the fructose in the Shi catalyst.

Jacobsen Catalyst

The sum of electronic and thermal free energies of the transition states for the epoxidation of cis/trans beta-methyl styrene were provided and are shown in table 16 and 17 below:

| Transition State | Total Free Energy (Hartree) | Total Free Energy (kJ mol-1) |

|---|---|---|

| S,R 1 | -3383.25956 | -8882748.649 |

| S,R 2 | -3383.25344 | -8882732.589 |

| R,S 1 | -3383.25106 | -8882726.335 |

| R,S 2 | -3383.25027 | -8882724.261 |

The transition states with the lowest free energy are S,R 2 and R,S 2 as shown in table 16. Where the difference in free energy between these two states (ΔG) is 8.328 kJ mol-1. Hence the equilibrium constant (K) is 0.03469, giving an enantiomeric excess (ee) of 93.4 %, which is similar to the value reported in literature[13](92.0 %), which highlights the selectivity of the epoxidation reaction using the Jacobsen catalyst.

| Transition State | Total Free Energy (Hartree) | Total Free Energy (kJ mol-1) |

|---|---|---|

| S,S 1 | -3383.262481 | -8882756.320 |

| S,S 2 | -3383.257847 | -8882744.154 |

| R,R 1 | -3383.253816 | -8882733.571 |

| R,R 2 | -3383.254344 | -8882734.957 |

The transition states with the lowest free energy are S,S 2 and R,R 1 as shown in table 17 above. The difference in free energy between these two states (ΔG) was determined to be 10.583 kJ mol-1 where the equilibrium constant (K) is 0.01396, giving an enantiomeric excess (ee) of 97.2 %. No comparisons were made with this value of ee as there were no literature available for this epoxidation reaction.

Non-covalent interactions (NCI) in the active site of the reaction transition state between R,R-stilbene and the Shi Catalyst

Non-covalent interactions (NCI) refers to hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions and dispersion interactions between close approaches of pairs of atoms. The NCI interactions were computed using Gaussview and the result obtained is shown on diagram 23 on the left. This will allow us to rationalise the stereoselectivity of the epoxidation of R,R-stilbene using the Shi Catalyst.

As shown in diagram 23 on the right, R,R-stilbene interacts with the Shi Catalyst in a spiro transition state, where many attractive interactions are present (green interaction in diagram 23) between the electronegative anomeric oxygen in the catalyst and the electron rich phenyl and attractive interactions are also between the oxygen atoms in the 5-membered ring in the catalyst and the olefin in R,R-stilbene. No attractive interactions were present on the adjacent phenyl ring in R,R-stilbene, hence it explains why using a Shi Catalyst preferentially forms a trans alkene.

Attractive interactions was observed between the oxygen atoms of the 5-membered ring of catalyst and a hydrogen atom on the olefin in R,R-stilbene, which might indicate a presence of hydrogen bonding.

R,R-stilbene interacts with the Shi Catalyst in a spiro transition state due to the favourable overlap between the C=C antibonding pi* orbital and the lone pair of electron on the dioxirane oxygen, which in turn leads to a stabilising interaction. This is not present when the transition state is planar[34] where planar transition states are favourable for trisubstituted olefins.

Electronic topology (QTAIM) in the active-site of the reaction transition state

The transition state between R,R-stilbene and the Shi Catalyst was subjected to QTAIM analysis using Avogadro 2. The molecular graph generated is shown in diagram 24.

A bond critical point (BCP) is the point between two atoms in a bond where the electron density reaches a minimum. A BCP was observed to be present between one of the oxygen atoms on the Shi catalyst and the olefin carbon atom as shown in diagram 24, this indicates that the addition of the oxygen atom across the olefinic bond on R,R-stilbene is not concerted. The position of the BCP is in the middle between the oxygen and the carbon atoms, which indicates that a covalent bond is formed between the carbon and oxygen atom.

The BCP for the C-C bonds in the phenyl rings in R,R-stilbene is in the middle between the two carbon atoms, indicating a the presence of a C-C covalent bond. In the Shi catalyst, it was observed that the position of the BCP tends to be further away from the oxygen and closer to the carbon atom in a C-O bond. This is due to the fact that the oxygen atom is electronegative, pulling more election density towards it in the C-O bond, thus pushing the location of BCP towards the carbon atom.

The presence of BCPs between the oxygen atoms of the 5-memmbered ring of the Shi Catalyst and the hydrogen atom on the olefin of R,R-stilbene confirms the presence of hydrogen bonds, which was previously observed during NCI analysis.

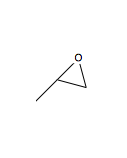

Suggested epoxide for further study

A search was done using Reaxys for small epoxides which has an optical rotation between -300 o and 300 o with a molecular weight of less than 200. Methyloxirane (shown in diagram 25) was chosen as the epoxide for further analysis. Methyloxiranes are used in clothing[35] and food packaging[35].

The corresponding alkene for Methyloxirane is propylene, which is readily available from Sigma-Aldrich. The optical rotatory power of methyloxirane in the absence of solvent[36](neat) is 13.2 o at 26 oC and at a wavelength of 589 nm. However, the optical rotatory power of methyloxirane in the presence of chloroform as a solvent[37] is -8.3 o at a wavelength of 589 nm at 25oC. This shows that the solvent used to measure the optical rotatory power of methyloxirane has an effect on the value of the obtained. However, temperature did not seem to have an effect on the optical rotatory power as a value of -8.26 o was obtained in the presence of chloroform at wavelength of 589nm at a temperature of 18oC[37].

References

- ↑ R. Hoffmann and R. B. Woodward , Acc. Chem. Res, 1968, 1, 17-22.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 D. Skala and J. Hanika, Petroleum and Coal, 2003, 45, 105-108.

- ↑ W. G. Etzkorn, S. E. Pedersen and T. E. Snead, Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology 2nd Edition, John Wiley and Sons, 1985, 6, 688.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Polymer Science and Technology, John Wiley and Sons, 5, 760-774.

- ↑ L. I. Kasyan,Russian Chemical Reviews, 1998, 67, 263-278.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 F. A. Anet and M. Squillacote, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1975, 97, 3244-3246.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 W. S. Johnson, V. J. Bauer, J. L. Margrave, M. A. Frisch, L. H. Dreger and W. N. Hubbard, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1961, 83, 606-614..

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 W. F. Maier and P. Von Rague Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103, 1891.

- ↑ Q. Lo, Gaussian Job Archive C20H30O1S2, 2014 ; DOI:10042/27344

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 10.8 L. Paquette, N. A. Pegg, D. Toops, G. D. Maynard and R. D. Rogers, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1990, 112, 277-283; DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0

- ↑ Q. Lo, Gaussian Job Archive C20H30O1S2, 2014 ;DOI:10042/27350

- ↑ E. Cuevas and G. Juaristi, The anomeric effect, CRC Press, Boca Raton,1995.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 E. N. Jacobsen, W. Zhang, A. R. Muci, J. R. Ecker and L. Deng, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1991, 113, 7063-7064; DOI:10.1021/ja00018a068

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 R. W. Murray and K. Iyanar, J. Org. Chem., 1998, 63(5), 1730-1731; DOI:10.1021/jo9719160

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 S. Wu, A. Li, Y. S. Chin and Z. Li, ACS Catal., 2013, 3, 752-759; DOI:10.1021/cs300804v

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 Z. X. Wang, L. Shu, M. Frohn, Y. Tu and Y. Shi, Org. Syn., 2003, 80, 9-17.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 H. Hachiya, Y. Kon, K. Takumi, N. Sasagawa, Y. Ezaki and K. Sato, Synthesis, 2012, 44, 1672-1678; DOI:10.1055/s-0031-1290948

- ↑ Q. Lo, Gaussian Job Archive C8H8O1, 2014 ; DOI:10042/27346

- ↑ Q. Lo, Gaussian Job Archive C9H10O1, 2014 ; DOI:10042/27347

- ↑ Q. Lo, Gaussian Job Archive C8H8O1, 2014 ;DOI:10042/27348

- ↑ Q. Lo, Gaussian Job Archive C9H10O1, 2014 ; DOI:10042/27349

- ↑ Q. Lo, Gaussian Job Archive C8H8O1, 2014 ; DOI:10042/27351

- ↑ Q. Lo, Gaussian Job Archive C8H8O1, 2014 ; DOI:10042/27352

- ↑ Q. Lo, Gaussian Job Archive C8H8O1, 2014 ; DOI:10042/27353

- ↑ Q. Lo, Gaussian Job Archive C8H8O1, 2014 ; DOI:10042/27354

- ↑ Q. Lo, Gaussian Job Archive C9H10O1,2014 ; DOI:10042/27355

- ↑ Q. Lo, Gaussian Job Archive C9H10O1, 2014 ; DOI:10042/27356

- ↑ Q. Lo, Gaussian Job Archive C9H10O1, 2014 ; DOI:10042/27357

- ↑ Q. Lo, Gaussian Job Archive C9H10O1, 2014 ;DOI:10042/27358

- ↑ V. S. Bettigeri, C. D. Forbes, A. S. Patrawala, C. S. Pischek and M C. Standen, Tetrahedron, 2009, 65, 70-76;DOI:10.1016/j.tet.2008.10.019

- ↑ H. Lin, Y. Liu, J. Qiao, Z. L. Wu and H. Lin, Tetrahedron Asymmetry,2011, 22, 134-137.; DOI:10.1016/j.tetasy.2010.12.022

- ↑ D. Chen, B. Nettles, Y. Shi, B. Wang, A. O. Wong, Y. X. Wu and M. X. Zhao, J. Org. Chem.,2009, 74, 3986-3989.; DOI:10.1021/jo900330n

- ↑ Y. Shi., B. Wang, A. O. Wong, M. X. Zhao, J. Org. Chem., 2009, 16, 6335-6338.;DOI:10.1021/jo900739q

- ↑ Z. X. Wang, L. Shu, M. Frohn, J. R. Zhang and Y. Shi, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1997, 119, 11224-11235.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 G. A. Skarja and M. H. May, US Pat., US2007/104678 A1, 2007

- ↑ M. Inoue, K. Chano, O. Itoh, S. Osamu, T. Sugita and K. Ichikawa, Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan, 1980, 53(2), 458-463.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 B. Franzus and J. H. Surridge, J. Org. Chem., 1966, 31, 4286-4288. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Franzus" defined multiple times with different content