Rep:Mod:qhyd1234

Module One: Organic

The Hydrogenation of the cyclopentadiene dimer

The exo- cyclopentadiene dimer (product 1) was modelled first using ChemBio 3D. Its geometry was optimized using the MM2 optimization, and the resultant molecule is shown below. The energy of the molecule was calculated to be 133.432 kJ/mol.

Product 1 |

The endo- dimer was then modelled in the same way(product 2). This molecule had an energy of 142.3088 kJ/mol.

Product 2 |

The calculated energy of the exo- dimer is lower than that of the endo- dimer. This, however, does not reflect the preferrec product of cyclopentane dimerisation as the major product is the endo- isomer. This suggests that the reaction is kinetically rather than thermodynamic controlled.

The exo-dimer can then undergo hydrogenation at either double bond to give product 3 or product 4. Product 3 (shown below) was optimized and the resultant molecule had an energy of 150.3767 kJ/mol.

Product 3 |

Product 4 is shown below. This was optimized so that it had an energy of 130.3795 kJ/mol.

Product 4 |

The energies of the products are summarized in the table below.

| Energy of product 1 (kJ/mol) | Energy of product 2 (kJ/mol) | Energy of product 3 (kJ/mol) | Energy of product 4 (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 133.432 | 142.3088 | 150.3767 | 130.3795 |

The relative energy of products 3 and 4 can be directly compared in order to suggest the thermodynamic product of the reaction. This can be done more thoroughly by considering the individual types of strain that have been added to give the overall energy of each molecule.

| Type of strain energy | Product 3 | Product 4 |

|---|---|---|

| Stretching (kJ/mol) | 5.243 | 4.588 |

| Bending (kJ/mol) | 78.894 | 60.713 |

| Torsion (kJ/mol) | 51.231 | 52.301 |

| Van der Waals’ (kJ/mol) | 17.613 | 14.487 |

| Hydrogen Bonding (kJ/mol) | 0.682 | 0.5888 |

Thermodynamics suggests that product 4 should be formed, as it is lower in energy. All individual strain in the molecules (such as stretching, bending etc) with the exception of torsion is lower in product 4. Thus, the double bond in the five-membered ring is easier to hydrogenate.

The Stereochemistry of Nucleophilic Additions to a Pyridinium Ring (NAD+ analogue)

Two reactions involving addition to a pyridinium ring were investigated. These were the addition of a methyl group (using MeMgBr) to an optically active derivative of prolinol (structure 5) and the second involves the reaction of a substituted pyridine ring with aniline.

The reaction of the prolinol derivative with MeMgBr

- The prolinol derivative shown below was modelled and its energy minimized. Once this had been done it was possible to see that the amide oxygen is pointing up relative to the plane of the pyridinium ring (the dihedral angle between six-membered ring and C=O is 25.1°).

Prolinol Derivative |

- This means that if the Grignard reagent approaches from the top face it can coordinate to the amide oxygen. Thus, when the methyl group attacks, it will attack from the top face. This explains the stereochemistry of the product (in which the methyl group is pointing up).

The reaction of a substituted pyridine ring with aniline

- This second example can be thought of in the same way as the first example, by considering the stereochemistry of the amide oxygen. As can be seen from the model below, this is again pointing up relative to the pyridinium ring (the dihedral angle between six-membered ring and C=O bond is 37.7°). Coordination of the incoming nucleophile to the amide oxygen can then take place, and the new group will add to the top face of the ring.

Structure 7 |

It is a little silly to model this interaction using MM2, as it is really an orbital interaction and Molecular Mechanics only considers the problem classically (using Hooke's law type models for bonding), electrostatic repulsions/attractions and Van der Waals' steric interactions. It would be much better to use a quantum mechanics model (such as the semi-empirical Molecular Orbital theory employed later) to visualise the overlap of the orbials involved.

The Stereochemistry and Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

Molecule 10 (shown below) is an intermediate in the synthesis of taxol. Its structure was minimized (with a resultant energy of 158.35 kJ/mol.)

Intermediate 10 from the synthesis of taxol |

Molecule 11 is another conformation of the same intermediate. This was also modelled (the lowest energy achieved was 185.34 kJ/mol).

Intermediate 11 from the synthesis of taxol |

From these calculations, it is possible to suggest that thermodynamic intermediate is molecule 10.

The double bond undergoes functionalisation very slowly. This could be because of two reasons:

- The molecule is sterically hindered; access to the double bond by electrophilic species will be very difficult.

- There could also be coordination of the incoming electrophile to the carbonyl oxygen. This would slow down the rate of reaction.

Inducing Room Temperature Hydrolysis of a Peptide

This section is considering the hydrolysis of an N-(2-hydroxyethyl)glycine amide at room temperature. Since this is achieved by carefully controlling the stereochemistry two structurally different molecules will be investigated. These are named peptide 13 and 14. Both of these peptides can exist in two forms, with the amide group axial or equatorial to the ring. Both of these structures must be investigated in order to rationalise the different rates of hydrolysis shown by each peptide. The equatorial form of peptide 13 is shown below (optimized energy is 72.113 kJ/mol)

Peptide 13 |

This is directly compared to the axial form of peptide 13 (optimized energy of 82.105 kJ/mol)

Axial peptide 13 |

These calculations suggest that the lower energy conformer has the amide group in the equatorial position. This is because there is much less steric hinderance between the amide (ethyl amido) group and the ring in this position. This is important to the reactivity of the peptide, as hydrolysis can only occur when the amide is in the equatorial position. Since this is the most stable conformation there will be a greater proportion of this conformer in solution and the reaction will therefore be faster. It can also be seen from the models that the axial conformer is perfectly set up to undergo intramolecular attack (alcohol oxygen lone pair on the carbonyl carbon) as these are already lined up in a chair-like six membered ring. There is also the possibility of hydrogen bonding between the axial hydrogens of the nearest cyclohexane ring and the alcohol oxygen. This would stabilise the conformation, meaning that it will be lower in energy.

Peptide 14 can now be considered (in both forms). Its equatorial conformer is shown below (optimized energy of 57.328 kJ/mol)

Equatorial peptide 14 |

The axial conformer was then optimized to give an energy of 75.771 kJ/mol. The equatorial conformer is, again, the lower conformer, as this conformer avoids steric clash between the ethyl amido group and the hydroxyl group. This provides an explanation for the much slower rate of hydrolysis; the only reactive conformation of peptide 14 is the axial conformation. Since this is less thermodynamically favoured the equatorial conformation (which is formed first) has to be converted to the axial form before it can undergo hydrolysis. Thus the rate of reaction is much slower.

Axial peptide 14 |

It is also possible that the fact that the amide and alcohol groups in peptide 14 are not as well aligned for the alcohol oxygen to attack (i.e. the six membered ring that is formed is not quite chair-like in either the axial or the equatorial conformer.) Also, there is only one potential hydrogen bond available.

Modelling Using Semi-emprical Molecular Orbital Theory

Semi-empirical molecular orbital theory will now be used in order to consider aspects of reactivity that can be attributed to the interactions of orbitals known as secondary orbial interactions. This would not be possible using the MM2 method that has hitherto been employed. The reaction chosen to examine the strengths and weaknesses of this approach is the regioselective addition of dichlorocarbene.

- The regioselective addition of dichlorocarbene

- In this reaction diene 1 (shown below) reacts with dichlorocarbene (or another electrophilic reagent) to give a monosubstituted product. The reaction can occur at either the syn- or the anti- double bond. The relative favourabilities of these two reactions will be predicted using the semi-empirical molecular orbital theory. The molecular orbitals will also be calculated and displayed.

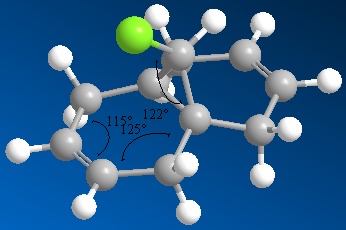

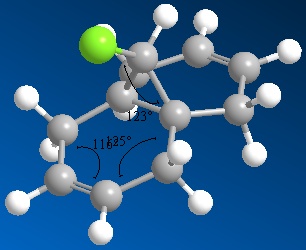

- Diene 1 was first modelled and its energy minimized using MM2 to give a rough initial energy. The initial model (MM2 minimized) is shown below.

Initial MM2 minimized model of diene 1 |

Note that the values of the angles in the ring have been placed badly by ChemBio3D. 116° corresponds to the angle shown in the bottom of the ring (as shown in the picture) and 124° corresponds to the other ring angle.

|

|

|---|

The geometry of this initial model was then minimized in Chem3D using the HF/STO-3G method. This method was used in order to calculate the molecular surfaces, especially the HOMO orbital (as this is the orbital that is most reactive to nucleophiles). The model produceed by this calculation is shown below. The jmol file has not been inserted as it is not vastly different from the MM2 optimized version above and since angles cannot be displayed using jmol it is more useful to display the picture (the angles in the ring are also labelled the wrong way round).

Finally, the structure was minimized and the vibrations calculated using the B3LYP/6-31G(d) method. There were problems with this initially, as the calculation was not run with enough iterations. This was overcome by re-scanning the ouput log file. This enabled the calculation to continue from where it had stopped. The molecule below is the result.

The structures produced are slightly different due to the different approaches used to minimize them. These differences are illustrated most easily by comparing the angles in the ring and the angle between the chlorine atom and the ring. These angles (shown in the pictures above) are summarised in the table below.

|

Angle a | Angle b | Angle c |

|---|---|---|---|

| MM2 minimized | 118 | 124 | 116 |

| STO-3G minimized | 122 | 125 | 115 |

| B3LYP/6-31G(d) | 123 | 125 | 116 |

The structures are different because the methods used to model them are different. The MM2 method is a purely classical method, whereas semi-empirical molecular orbital theory uses quantum mechanics. The semi-empirical theory should produce a better model of the molecule, as it considers the effect of the electrons and orbitals on the final geometry.

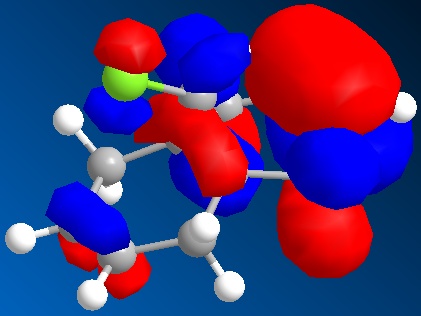

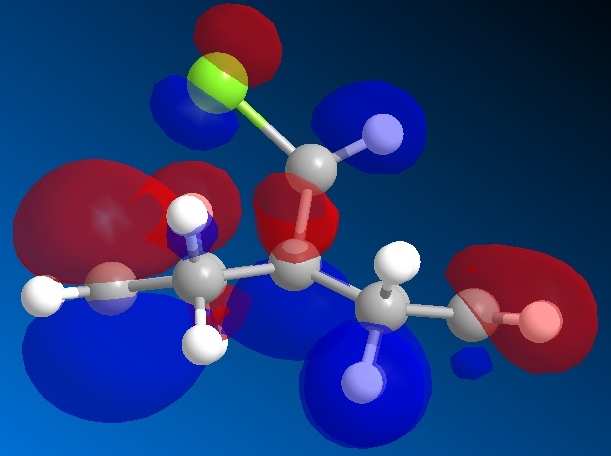

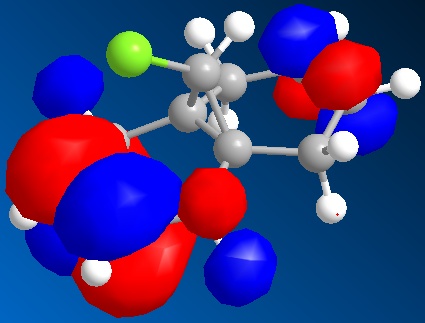

The molecular orbitals generated by the STO-3G method are shown below. The orbitals displayed are the HOMO-1, the HOMO, the LUMO, the LUMO+1 and the LUMO+2.

| The HOMO-1 |

|

|---|---|

| The HOMO |

|

| The LUMO |

|

| The LUMO+1 |

|

| The LUMO+2 |

|

The reaction itself (rather than the methods used to model it) was tested by investigating how easy it is to hydrogenate the syn double bond. This was done by replacing the said double bond with a single bond. This energy of the mono-alkene was also minimized by MM2, STO-3G and B3LYP/6-31G(d) methods. The resultant model is shown below.

Hydrogenated diene product |

The stretching frequencies of both molecules were also calculated by the B3LYP/6-31G(d) method, and these were displayed in GaussView. The main ones being investigated were the C-Cl stretches and the C=C stretches (one C=C stretch for the mono-alkene and two for the di-alkene). The frequencies of these stretches are displayed in the table below.

| Molecule | C-Cl stretching frequency cm-1 | C=C stretching frequency cm-1 |

|---|---|---|

| Di-alkene 1 | 264.294 very slight,

644.294 (IR 1.1393), 672.871 (IR 7.3982), 903.597 (IR 2.2224), 1322.48 (IR 5.2841) |

1740.76 (anti double bond)

1760.91 (syn double bond) |

| Mono-alkene | 290.67 (IR 2.5526)

Very slight 313.801 (IR 0.0702), 502.17 (IR 2.0729), 910.92 (IR 5.0361), 930.261 (IR 10.838), 1387.46 (IR 5.5582) |

1761.72 |

The C=C stretches reported are the ones with very strong displacement vectors. There were other vobrations involving the stretching of the C=C bond, but these were not pure stretches and so have not been included.

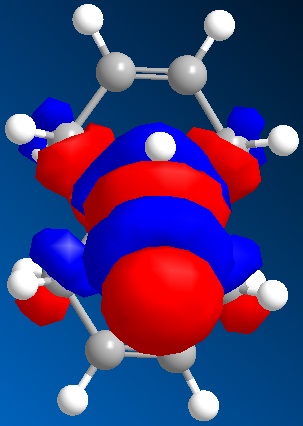

Structure Based Mini-project Using DFT Based Molecular Orbital Methods

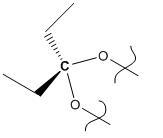

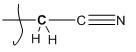

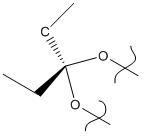

The reaction that was chosen to be studied is the β-Selective C-Allylation of a Ribofuranoside. The stereoselectivity of the reaction is found to be highly influenced by the transition state. From this point in the reaction there are two possible ways for the nucleophile to attack, outside attack or inside attack. Outside attack gives rise to the β-isomer and inside attack gives rise to the α-isomer. The reaction of a similar riboside (such as the allylation of 2,3,5-tri-O-benzyl-D-ribofuranosyl donors) have been shown to be selective towards the α-isomer whereas the reaction shown below gives the β-isomer as the major product. This is thought to be because of the increased steric bulk caused by the cyclic ketal protecting group on the di-hydroxyl functionality. This causes a steric clash when the nucleophile attacks the inside of the ring and favours outside attack. The particular reaction chosen for study here is with TMSCN (i.e. Nu = CN-)

The two diastereomeric products have been modelled using Chem3D and their NMR spectra predicted using the mpw1pw91 method (a DFT based method).

|

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The α-riboside | The β-riboside |

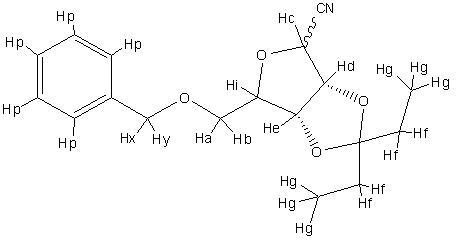

1H and 13C NMR spectra were taken for the product mixture. The ratio of products formed was determined by NOE spectroscopy. NMR data was reported[2] (J coupling values and chemical shifts). But these were not reported for the alpha isomer. Therefore, instead of comparing results, we will instead predict the 13C and 1H spectra of the alpha isomer.

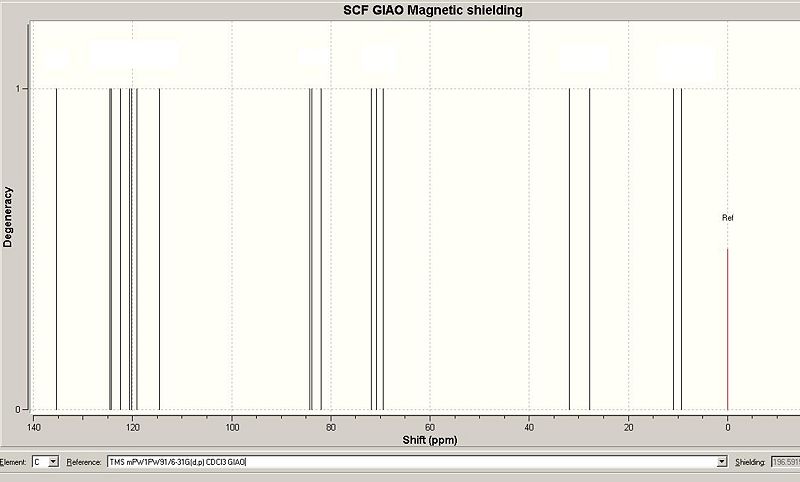

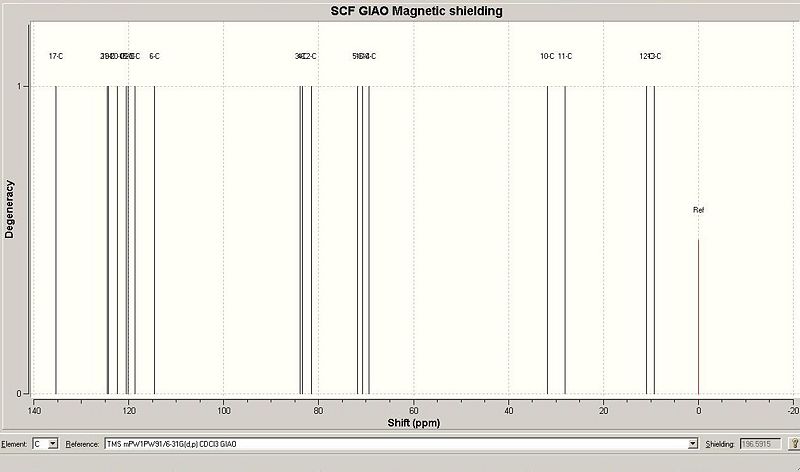

13C NMR Spectra

This was calculated using the DFT approach (chemical shifts for carbon were corrected accordingly). The predicted chemical shifts for the alpha isomer are shown below.

| The alpha anomer |  [3] [3]

|

|---|---|

| The beta anomer |  [4] [4]

|

The predicted chemical shifts of beta isomer were then compared with the measured ones (for numbered carbons see the image on the right).

| Predicted Chemical Shift (ppm) | Corresponding Carbon | Measured Chemical Shift |

|---|---|---|

| 137.895 | Carbon 17 | 137.4 |

| 127.075 | Carbon 21 | 128.5 |

| 126.767 | Carbon 19 | 128.2 |

| 124.972 | Carbon 20 | 128.0 |

| 123.023 | Carbon 18 | - |

| 122.716 | Carbon 22 | - |

| 121.177 | Carbon 9 | 118.2 |

| 117.075 | Carbon 6 | 118.1 |

| 86.4618 | Carbon 3 | 86.5 |

| 85.8417 | Carbon 4 | 85.6 |

| 84.1055 | Carbon 2 | 83.3 |

| 74.256 | Carbon 5 | 74.7 |

| 73.1919 | Carbon 16 | 73.6 |

| 71.8897 | Carbon 14 | 70.5 |

| 34.3418 | Carbon 10 | 29.4 |

| 30.5746 | Carbon 11 | 29.0 |

| 13.4653 | Carbon 12 | 8.5 |

| 11.791 | Carbon 13 | 7.5 |

The product was probably analysed in a mixture due to problems separating the two diastereoisomers. The normal methods of separation for enantiomers (chromatography and recrystalisation) would probably not be very effective in separating the alpha and beta anomers. There is a slight difference in dipole between the conformers (the beta anomer has a slightly stronger dipole) and so there may be a very slight difference in solubility in polar solvents, but this difference is unlikely to be very large (there are no formal charges and there is very little ionic character in either molecule).

The predicted chemical shifts are reasonably close to the measured chemical shifts, although it becomes less good at lower ppm. This is interesting, as the lower peaks have chemical shifts similar to protons and prediction of proton NMR is known to be less reliable. It can also be seen that there is not a great deal of difference between the two anomers and it would be challenging to attempt to differentiate between the two using 13C NMR.

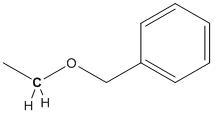

1H NMR Spectra

The proton spectra cannot be predicted using the method above, as it is not accurate enough to be useful. The coupling constants can be predicted using a different program (Janoccio). These are predicted using the Karplus equation.

| Computer assignment | Journal assignment | Chemical shift (ppm) | Multiplicity | Predicted coupling (α- anomer) (Hz) | Predicted coupling (β-anomer) (Hz) | Measured coupling (β-anomer) (Hz) |

| Hp | Phenyl | 7.36 | m | 8.22 | 8.22 | - |

| He | 1H, H-2 | 5.08 | dd | 6.6977, 5.9749 | 6.8642, 5.9749 | 1.7, 5.7 |

| Hd | 1H, H-3 | 4.83 | d | 6.977, 5.9749 | 5.9749 | 5.7 |

| Hc | 1H, H-1 | 4.76 | d | 5.6713 | 6.8642 | 1.7 |

| Hx | benzyl | 4.67 | d | - | - | |

| Hy | Benzyl | 4.47 | d | - | - | |

| Hi | 1H, H-4 | 4.44 | m | 5.4882, 4.6634, 10.6779 | 3.1829, 10.6618, 4.4119 | - |

| Ha | 1H, H-5a | 3.61 | dd | 10.6779 | 4.4119, 10.6618 | 3.4, 10.3 |

| Hb | 1H, H-5a | 3.58 | dd | 10.6779 | 4.4119, 10.6618 | 4.0, 10.3 |

| Hf | CH2-CH3 | 1.69 | dd | 3.0465, 3.0881, 13.934 | 4.567, 1.8389, 13.1578 | 7.4, 14.8 |

| Hf | CH2-CH3 | 1.59 | dd | 4.3173, 4.4819, 13.7833 | 2.6411, 3.5349, 13.9206 | 7.4, 14.8 |

| Hg | CH2-CH3 | 0.96 | t | 3.0465, 3.0881, 13.934 | 4.567, 1.8389, 13.1578 | 7.4 |

| Hg | CH2-CH3 | 0.87 | t | 4.3173, 4.4819, 13.7833 | 2.6411, 3.5349, 13.9206 | 7.4 |

The protons are numbered in the picture on the right. The journal referenced did not label the hydorgens, so despite assigning the peaks it is not really possible to compare assignments The only assignments were given to the shift at 7ppm (assigned to the phenyl protons), the ones at 1.6 and 1.5 (assigned to methylene protons) and 0.96 and 0.87 (assigned to the methyl protons). This agrees with the assignment given by the calculation.

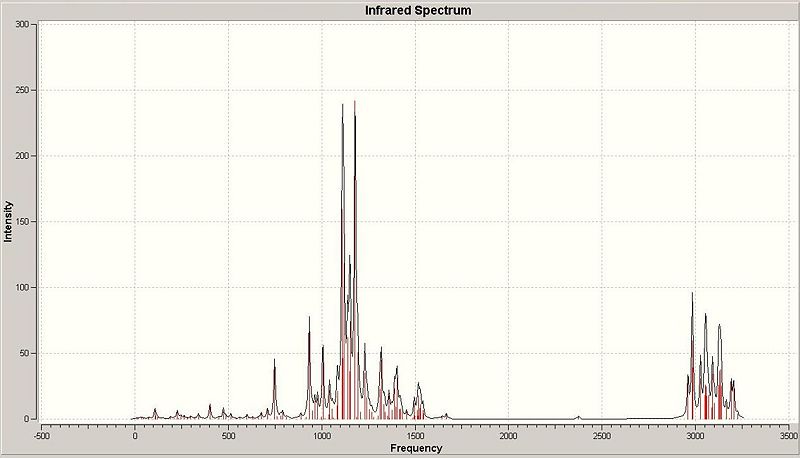

IR Spectra

The IR spectrum predicted by the calculation is shown below. The spectrum below is of the beta anomer; both spectra are not shown as they are very similar. This is not suprising, as it is not generally possible to distinguish between diastereoisomers using infra-red spectroscopy.

The predicted frequencies of the vibrations are compared to standard frequencies in the table below (only vibrations that are observable in the spectrum have been included). Note that the CN stretch is not observable in the IR spectrum. This stretch has been predicted by the calculation (at 2375.03 cm-1) but as it has an IR intensity of 2.2973 it is not suprising that is cannot be seen on the spectrum.

| Predicted frequency of absorption (cm-1) | Corresponding vibration | Expected frequency (cm-1) |

|---|---|---|

| 749.33 | Phenyl proton stretch | 690 - 900 |

| 933.741 | vibration #48 (a "methyl wiggle") | - |

| 1006.43 | vibration #55 (furan C-O stretch) | 1000 - 2000 |

| 1112.78 | vibration #66 (Generic wiggle) | - |

| 1178.64 | vibration #71 (OBn group C-O stretch) | 1000 - 2000 |

| 1232.11 | vibration #76 (Generic wiggle) | - |

| 1318.99 | vibration #83 (Generic wiggle) | - |

| 2984.56 | vibration #112 (CH stretch) | around 3000 |

| 3054.28 | vibration #117 (Another CH stretch) | around 3000 |

| 3133.24 | Vibration #126 (Another CH stretch) | 3000 |

The sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies= -1055.063509

Optical Rotation

Optical rotation was not predicted for either of the porducts; as they are not enantiomers this particular piece of information is not very useful.

References

- ↑ Journal reference DOI:10.1021/ol8018743

- ↑ Supporting information such as NMR data can be found on the Organic Letters website DOI:10.1021/ol8018743

- ↑ Published NMR spectrum: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-1183

- ↑ Published NMR spectrum: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-1175