Rep:Mod:pv=nrt

Module 1

1. Dimer of Cyclopentadiene and its Hydrogenation

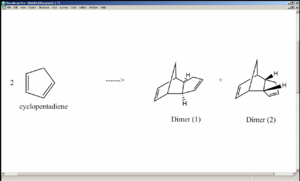

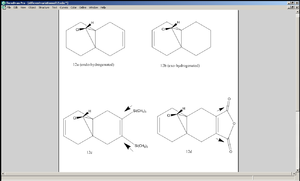

Dimerisation of cyclopentadiene can lead either to the exo-product (structure 1), where the two rings of the reactants are positioned in such a way that intramolecular steric repulsion is minimised, or to the endo-product (structure 2), where the two rings converge. Steric considerations suggest that structure 1 is lower in energy, yet it turns out that dimer 2 forms more readily[1].

In this experiment the energies of the two possible dimer products were calculated using MM2 method, whereby each molecule was forced to adopt a geometry such that the overall energy was minimised. In this calculation method the atoms and bonds were treated in a classical manner[1].

| Dimer 1 | Dimer 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| stretch | 1.2923 | 1.2454 |

| bend | 20.587 | 20.8603 |

| stetch-bend | -0.8413 | -0.832 |

| torsion | 7.6715 | 9.59039 |

| non-1,4 vdW | -1.4358 | -1.5083 |

| 1,4 vdW | 4.232 | 4.3012 |

| dipole/dipole | 0.3778 | 0.4448 |

| ETOT | 31.8834 | 34.0153 |

| All energy values in kcal/mol |

As is shown in the table, MM2 calculation agrees that the exo-dimer 1 is lower in overall energy than the endo-dimer 2 and so 1 is the thermodynamic product. In particular, the energy associated with torsion was higher in 2 than in 1. The fact that 2 is formed more readily, despite being relatively high in energy, indicates that it is the kinetic product, meaning its transition state is lower in energy than that of 1. Investigating the nature of the transition state is beyond the capability of MM2 and electronic considerations must be made.

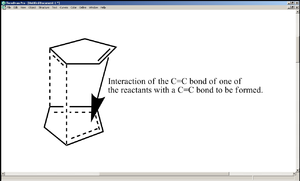

As shown in the diagram on the right, the transition state in the reaction leading to 2 has an interaction between the unreacting C=C bond and a C=C bond about that is about to be formed (in other words, a build up of π electron density)[2]. This lowers the energy of the transition state and hence the activation energy of the reaction, making the rate of formation of 2 far greater than that of 1. The geometry of the transition state explains the fact that 2 was particularly higher in energy than 1 in terms of torsion (tetra-atomic[1]) - for the interaction mentioned above to take place, the unreacting C=C bond would have to be positioned sufficiently close to the C=C bond to be formed, which obliges the two cyclopentadiene rings to align themselves nearly parallel to each other.

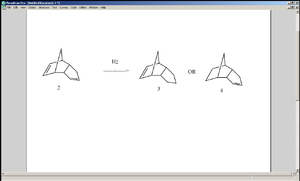

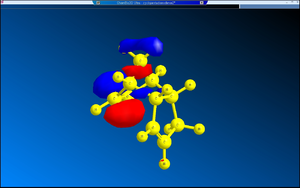

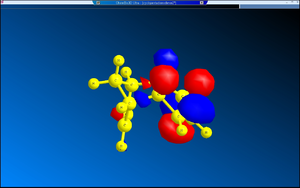

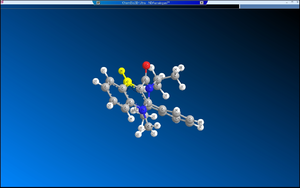

When hydrogenation is carried out on 2, despite the fact that there are two C=C bonds available, only one of the possible mono-alkene product is formed. MM2 calculation shows that 4 is lower in overall energy than 3, but this does not guarantee that it will be formed more readily, since 3 may well be favoured kinetically. In order to deduce the kinetic product, the difference between the two C=C bonds must be examined. MM2 calculations show the C=C bond length to be 1.338Å for the one on the left (cis to the propyl group pointing upwards) and 1.337Å for the other one (not enough difference to suggest a difference in reactivity). However, the difference in their reactivity can be explained by observation of their molecular orbitals.

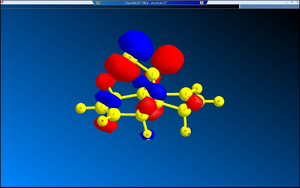

The π orbital cis to the propyl group corresponds to the HOMO of the molecule, whereas that of the orbital trans to the propyl group corresponds to the HOMO-1 orbital. In other words, the π bond trans to the propyl group lies lower in energy than the other C=C bond (this requires quantum mechanical calculations). In hydrogenation of alkenes, π electrons are taken away from the C=C double bond, so if two C=C bonds are present, the one that is higher in energy will be broken and its electrons will be detached more easily. The fact that 4 is also lower in overall energy implies that it is both the kinetic and the thermodynamic product.

| 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|

| stretch | 1.2067 | 1.0963 |

| bend | 18.8637 | 14.5074 |

| stetch-bend | -0.7528 | -0.5493 |

| torsion | 12.2396 | 12.4972 |

| non-1,4 vdW | -1.5532 | -1.0507 |

| 1,4 vdW | 5.7649 | 4.5124 |

| dipole/dipole | 0.1632 | 0.1407 |

| ETOT | 35.9322 | 31.154 |

| All energy values in kcal/mol |

2. Nucleophilic Additions on NAD+ Analogues

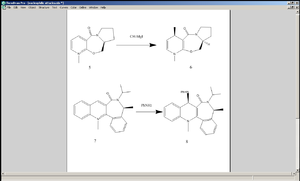

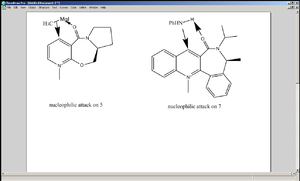

The two NAD+ analogues (both 5 and 7) undergo stereospecific nucleophilic addition reactions. In the case of Grignard reagent attacking 5, the Lewis acidic Mg coordinates to the oxygen of the carbonyl group adjacent to the pyridine ring[3].

| 6 (syn) | 6 (anti) | 8 (syn) | 8 (anti) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETOT (kcal/mol) | 29.3009 | 30.2059 | 17.5513 | 22.5601 |

Again, MM2 method was used to calculate the energy values of each molecule investigated. In both products 6 and 8, the anti isomer (where the nucleophile is pointing away from the plane of the diagram) turns out to be higher in energy than the syn isomer (where the nucleophile is coming out). However, as mentioned above, the two reactions shown here are stereospecific, meaning that mechanistically it is not possible to generate the anti isomers.

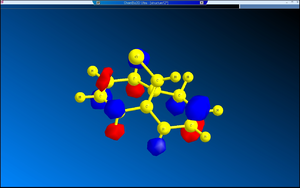

The C=O, as shown on the diagram, is not co-planar with the pyridine ring but is inclined at an angle of 44°, coming out of the plane. The methyl group of the Grignard reagent has no option but to attack the pyridine ring from above, since the methyl group is attached to the Mg (Mg-C bond is polar but is still covalent, not quite ionic). In addition, the C-N bond of the amide is pointing downwards, meaning the intervention of nucleophiles from the bottom phase is prohibited sterically.

Similarly, in the case of PhNH2 attacking 7, the C=O is coming out of the plane, inclined at an angle of 42°. One of the protons attached to the nitrogen coordinates to the oxygen of the carbonyl group by means of hydrogen bonding, and again the nitrogen of the nucleophile attacks the pyridine ring from the top face. Again, the C-N bond of the amide points downwards, obstructing the entrance of nucleophiles from underneath.

A possibly more accurate way to represent 5 and 7 is to draw the C=O bond with a pair of bold wedged lines[4] and the C-N with a hashed wedged line to indicate clarify the fact that they are not co-planar with the pyridine ring.

3. Stereochemistry and Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol.

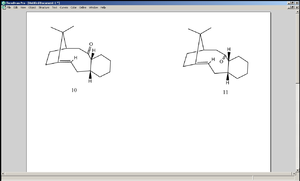

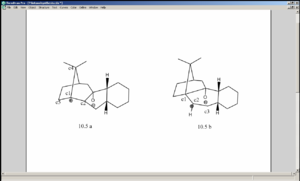

The atropisomers 10 and 11 are intermediates in taxol synthesis. It is assumed that when 10 isomerises into 11 and vice versa[1], the interconversions are carried out by the intramolecular interactions between the alkene and the carbonyl group (which is electrophilic), which temporarily forms turns the carbonyl into an alkoxy group, giving it a chance to flip. MM2 calculation shows the overall energy of 10 to be 54.358kcal/mol, and that of 11 to be 50.589kcal/mol, hence giving favouring the latter in energetic terms.

The interaction between the alkene and the carbonyl[5] results in a temporary positive charge build up on either of the carbon atoms C1 (the one on the cyclopentane ring) or C2 (the one adjacent to C1), forming intermediate 10.5a or 10.5b respectively during the interconversion process (please see the diagram above). According to MM2, the energy of 10.5a is -21.5694kcal/mol and that of 10.5b is -28.8219 kcal/mol, implying the preference of the positive charge build up on C2. (In reality 10.5a and 10.5b may be transition states rather than intermediates[5], since according to Hammond’s postulate the factors stabilising a transitions state would also apply to an intermediate which is similar in structure and vice versa). The unusual stability of the alkene can be explained by examining the geometry adopted by the carbon atom C2 as it accommodates full/partial positive charge. In the structure of 10.5b, after energy minimisation by MM2 the bond angles C1-C2-C3, C1-C2-H and C3-C2-H were shown to be 121.5, 115.9 and 115.0 respectively. In 10.5a, the angles C5-C1-C4, C5-C1-C2 and C2-C1-C4 were 105.9, 117.1 and 119.0. In other words, both in 10.5a and 10.5b the carbon which had to accommodate the full/partial positive charge had a reluctance to adopt a planar geometry (which sp2 carbons do). This alkene was made to be rather rigid by being attached to a cyclopentadiene ring, while being part of another ring. This is thought to be the origin of the difficulty for either the C1 or C2 to adopt a planar geometry, thus making it less susceptible to electrophilic additions than ordinary alkenes.

4. Hydrolysis of Peptides

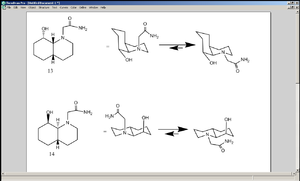

In cyclic compounds, bulky substituents such as CH2CONH2 prefer to be in equatorial positions in order to avoid diaxial compression with the protons that are put in axial positions on the rings[2][6]. In the case of 13, the -OH group that is to hydrolyse the amide is also in the equatorial position, meaning the position of equilibrium favours the two reacting functional groups to be in each other’s proximity. In 14, though, the -OH group is in an axial position and so it is not close enough to hydrolyse the amide unless the amide also takes up an axial position, which is sterically disfavoured. In nature peptides take far longer time to be hydrolysed unless a specific enzyme is used, since one of the substituents attached to the nitrogen of the peptide bond is an amino acid group, which offers far greater steric protection than a proton (in compounds 13 and 14 both of the substituents attached to the nitrogen, other than the carbonyl, were protons.

| compound | N-substituent | ETOT (kcal/mol, calculated by MM2) |

|---|---|---|

| 13 | axial | 19.8052 |

| 13 | equatorial | 21.2340 |

| 14 | axial | 24.4569 |

| 14 | equatorial | 24.0948 |

It is rather mysterious as to why having the N-substituent in the equatorial position leads to higher energy than in the axial position in 13. This may be a result of the limitations (if not inability) of MM2 in taking the effect of the presence of lone electron pairs into account when predicting the all the steric factors within a molecule (both nitrogen and oxygen have lone pairs that can form hydrogen bonds with a proton attached to the ring, or cause intramolecular repulsions with bonding electron pairs elsewhere inside the molecule).

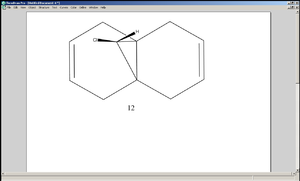

Regioselective Electrophilic Attack on a Cyclic Diene

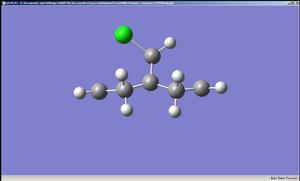

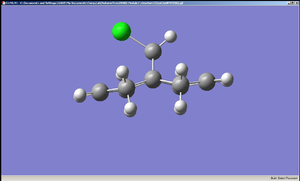

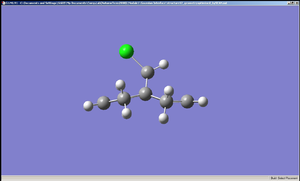

The cyclic diene 12 undergoes electrophilic addition specifically at the C=C bond that is exo (anti) to the Chlorine atom. In this experiment the optimised geometry of 12 was first investigated by using three different calculation methods, namely MM2, HF/STO 3G and B3LYP/6-31G.

The diagrams of the optimised geometry were all taken from the side, along the plane parallel to the C=C bonds (both the C=C bonds are positioned parallel to the plane of the diagram). At first glance there seems to be no difference but a careful observation reveals that in MM2 and HF optimised geometries the two rings look symmetrical with the mirror place cutting through the Cl – C – H angle but in the case of B3LYP optimised geometry the rings are no longer symmetrical – the ring endo (syn) to the chlorine straightens out while the ring exo (anti) to the chlorine remains slightly bent. One possible explanation is that this difference arises from anomeric effect – whereby the π electrons of the C=C anti to the chlorine interacts with the C-Cl σ* orbital[7]. If this were the case, there should be a weakening of the C-Cl σ bond, which would result in increased C-Cl bond length and decreased distance between C’ (the carbon to which the chlorine is attached) the midpoint of the C=C anti to the Cl[7].

| MM2 | HF/STO-3G(d) | B3LYP/6-31(G) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-Cl bond length (Å) | 1.760 | 1.760 | 1.760 |

| (C=C)-C' distance (Å) | 4.662 | 4.668 | 4.668 |

| (N.B. C' is the carbon to which the Cl is bound) |

The table shows that there are no significant differences between the three obtained geometries in C-Cl bond lengths or the distance between C’ and the midpoint of C=C. This, of course, does not verify the theory that the anomeric effect mentioned above actually takes place. Therefore, an alternative method was used to investigate the property of a particular C-Cl bond -to obtain its IR stretching frequency.

The stretching frequencies of C-Cl were investigated in a number of variations of 12, in addition to 12 itself. The variation 12e, with a CN replacing one of the hydrogen atoms located on the C=C anti to C-Cl was also used.

| compound | C-Cl stretch (cm-1) | C=C stretch (cm-1) | C-Cl bond length (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 688, 777 | N/A | 1.760 |

| 12a | 686, 779 | N/A | 1.794 |

| 12b | 676, 777 | 1517, 1761 | 1.798 |

| 12c | 666, 786 | 1336, 1508 | 1.760 |

| 12d | 678, 720 | N/A | 1.794 |

| 12e | 678, 768 | N/A | 1.795 |

It turns out that the C-Cl stretching frequency is not altered so much by the interaction of its anti-bonding orbital with a π electron density, even in the presence of an electron withdrawing/donating group adjacent to the C=C concerned (it was predicted that an electron donating substituent such as Si(CH3)3 would encourage the delocalisation of C=C π electrons and so their anomeric interaction with C-Cl σ*, and the opposite for electron withdrawing groups such as CN and CO). One point to consider is that adding substituents makes the overall molecule heavier, thus decreasing the value of wavenumber (which is inversely proportional to the reduced mass of the system). In the case of 12d, the wavenumber of C-Cl was lower than that of other variations of 12 but most of this decrease may be merely a result of the increased effective mass of the C’ and the Cl. Also the C-Cl bond length does not appear to be affected by the availability of those π electrons for back bonding.

A possible implication of these results is that the preference for 12 to undergo hydrogenation on the C=C bond syn to the Cl is a result in the difference in energies of the two C=C bonds present. Molecular orbital calculation using Huckel method shows that the C=C bond syn to the Cl atom is part of the HOMO-1 orbital of the molecule, whereas the C=C bond anti to the Cl is part of the HOMO-3 orbital. This implies that the π orbital anti to the Cl is more tightly held to by the carbon atoms sandwiching it: in fact it is so tightly held that the anomeric effect between that and C-Cl σ* is insignificant, if it does take place at all.

Mini-Project: Allylic Substitution followed by Coupling

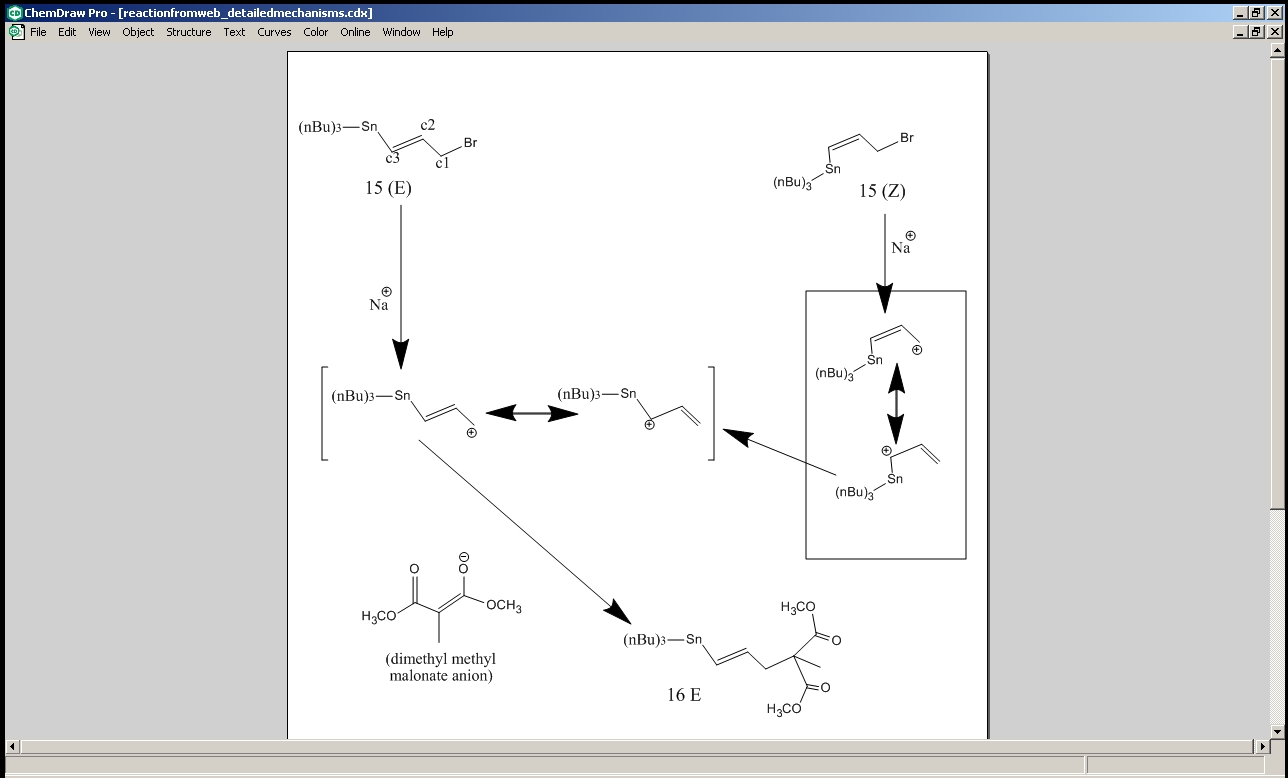

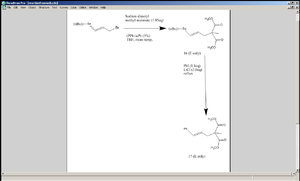

In the following reaction sequences, an allylic bromide 15 underwent a nucleophilic substitution (that displaced the bromide) that was then coupled with a halobenzene to substitute one of the substituents directly attached to the alkene.

The starting material can have E or Z geometry about the C=C bond; either way, compound 16 is meant to be exclusively E[8], which goes on to be converted to 17, which also is expected to show the E-isomer only.

The reason why the E/Z isomerism of 15 should not make a difference is that the nucleohphilic substitution process is carried out via SN1 mechanism. Cleavage of the C-Br bond leaves an allylic carbocation, which is resonance stabilised. When Z loses a bromide, in the latter resonance form of the carbocation generated, the bond between the carbon atoms C2 and C3 is a single bond and so rotation about that bond is allowed. Any stannane substituent that is initially positioned cis to the –CH2Br takes this opportunity to shift to the trans position (by which steric repulsion is reduced). The dimethyl methyl malonate anion attacks the C1 after this rotation of the stannane substituent. The dimethyl methyl malonate anion prefers to carry out the nucleophilic attack via the central C carbon which is relatively soft, rather than via the oxygen, which is harder, because allylic carbocations are soft electrophiles. Also steric repulsion favours the attack on C1 rather than on C3. The E and Z isomers of 17 can be distinguished by means of 1Hnmr spectroscopy. Here the DFT method was used to calculate both the optimal geometry and the nmr data of the two versions of 17. In the E isomer, Ha and Hb are trans to each other (where Ha and Hb are the two hydrogen atoms of the ethene group, with Ha being the one closer to the phenyl group) and so the coupling constant between them should have a value between 14 and 18Hz, whereas in the Z isomer, the same protons are cis to each other and so their coupling constants should be between 10 and 12Hz. Additionally in the E isomer, Hb is closer to the benzene ring than it is in the Z isomer and so it is expected to be more deshielded by the ring current of the benzene, causing it to appear lower down the field on the spectrum.

| Z | E | *literature | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O=**[C]OCH3 (×2) | 169.7, 168.4 | 171.4, 169.1 | 174.0, 173.9 | |

| C3 | 133.3 | 135.7 | 138.2/138.1 | |

| C2 | 132.5 | 126.4 | 135.7/133/9 | |

| Ph | 128.6, 128.1, 127.3, 126.6, 125.8, 125.0 | 132.5, 127.5, 127.2, 127.1, 125.8, 121.0 | 130.3/130.0, 129.8/129.3, 128.4, 127.8, 127.4, 125.7 | |

| R[C]CH3(COCH3)2 | 57.3 | 58.0 | 54.1/52.8 | |

| O[C]H3 (×2) | 53.7, 53.5 | 53.7, 53.4 | 55.9, 55.6 | |

| C1 | 39.1 | 43.2 | 41.0/35.7 | |

| CH3 | 25.6 | 25.5 | 20.4/15.4 |

| Z | E | Z (literature) | E (literature) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ph | 8.09, 8.06, 8.04, 7.93, 7.78 | 8.19, 8.03, 7.97, 7.87, 7.70 | 7.20 (×5) | 7.20 (×5) |

| Ha | 7.27 | 7.08 | 6.39 | 6.51 |

| Hb | 6.09 | 7.13 | 5.50 | 6.05 |

| methoxy H | 4.36, 4.35, 4.34, 4.32, 4.25, 4.25 | 4.45, 4.36, 4.32, 4.28, 4.27, 4.26 | 3.63 (×6) | 3.68 (×6) |

| CH2 | 3.90, 3.49 | 3.69, 2.87 | 2.88 (×2) | 2.72 (×2) |

| methyl H | 2.53, 2.46, 1.77 | 2.19, 1.96, 1.82 | 1.35 (×3) | 1.41 (×3) |

* The literature gave the same set of 13C nmr shift values for the E and Z versions of 17

** The carbon atom(s) whose peaks were tabulated where dispayed in italics enclosed by brackets.

The 3JHH coupling constants between Ha and Hb were measured on Janocchio, and the value in the E isomer was shown to be 8.2191Hz, with an angle of 179.4° between the C3-Ha and C2-Hb bonds. The coupling constant value of the Z isomer turned out to be 8.2191Hz, with an angle of 1° between the C3-Ha and C2-Hb bonds. These values of 3JHH coupling constants are not sufficiently different from one another to distinguish the E isomer from the trans; however their lower magnitudes (compared to those of normal disubstituted alkenes) can be explained by assuming that the Ha, being close to a π electron density (of the phenyl group), was pulled away from the C3 atom. This resulted in the distance between Ha and Hb being significantly larger than in ordinary disubstituted alkenes, thus weakening the coupling between the two.

Looking at the 1H nmr shifts of the phenyl and allylic protons obtained from SCAN and comparing them with those of the literature, it is probable that the calculation method used by SCAN overestimated the effect of the presence of aromaticity within the molecules concerned. It is interesting to note that according to the data obtained from SCAN, Hb is more deshielded than Ha in the E isomer. This is perhaps in agreement with the above theory that the Hb atom is indeed attracted by the phenyl group in the case of the E isomer far more strongly than in the Z version. Although this is contradictory to the literature values of proton chemical shifts, it is sufficiently clear that whether the E isomer or the Z is produced in the synthesis of 17 can be elucidated by the observation of the 1H nmr peak of Hb. This seems problematic due to the existence of the peak of Ha in the vicinity, but if 17 is synthesised with Ha replaced by a deuterium atom in the starting material 15 then the geometry of the final product would be elucidated (as all other protons emerge sufficiently far from Ha and Hb on the 1H nmr spectrum.

References

1. https://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki

2. Organic Chemistry by Clayden, Greeves, Warren and Wothers, Oxford University Press, 2005

3. # A. G. Shultz, L. Flood and J. P. Springer, J. Org. Chemistry, 1986, 51, 838. DOI:10.1021/jo00356a016

4. # Leleu, Stephane; Papamicael, Cyril; Marsais, Francis; Dupas, Georges; Levacher, Vincent. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, 2004, 15, 3919-3928. DOI:10.1016/j.tetasy.2004.11.004 , DOI:10.1016/j.tetasy.2004.11.004

5. # S. W. Elmore and L. Paquette, Tetrahedron Letters, 1991, 319; DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0

6. # M. Fernandes, F. Fache, M. Rosen, P.-L. Nguyen, and D. E. Hansen, 'Rapid Cleavage of Unactivated, Unstrained Amide Bonds at Neutral pH', J. Org. Chem., 2008, 73, 6413–6416 ASAP: DOI:10.1021/jo800706y

7. #B. Halton, R. Boese and H. S. Rzepa., J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 2, 1992, 447. DOI:10.1039/P29920000447

8. # Michael G. Organ,* Jeremy T. Cooper, Lawrence R. Rogers, Fariba Soleymanzadeh, and Timothy Paul, J. Org. Chem., 2000, 65 (23), pp 7959–7970, DOI:10.1021/jo001045l