Rep:Mod:pm3412

Optimising EX3 molecules

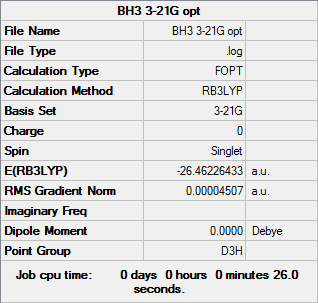

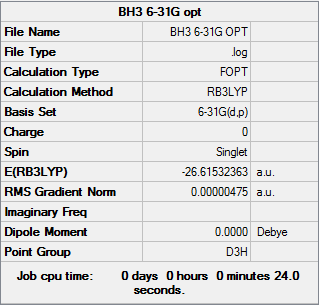

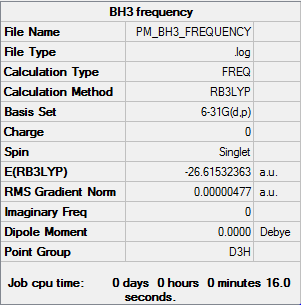

BH3

B3LYP/3-21G

Optimisation log file can be found here

B3LYP/6-31G (d,p)

Optimisation log file can be found here

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000009 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000006 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000038 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000025 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-5.342731D-10

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found. |

|

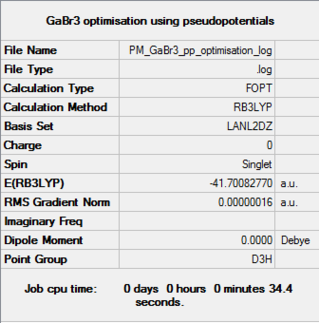

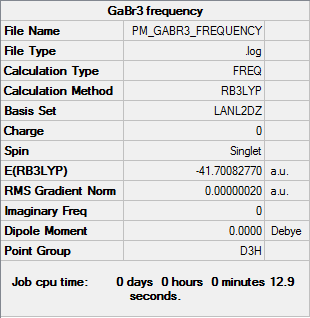

GaBr3

B3LYP/LanL2DZ

Optimisation file DOI:10042/31206

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000000 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000000 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000003 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000002 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.307738D-12

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found. |

|

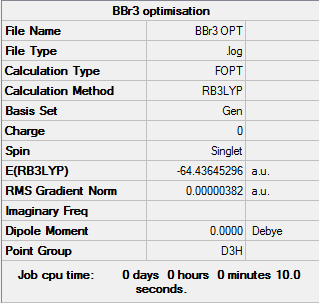

BBr3

B3LYP/GEN

Optimisation file DOI:10042/31244

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000008 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000005 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000036 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000023 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-4.027380D-10

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found. |

|

Geometry Comparison

| BH3 | BBr3 | GaBr3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| r(E-X) | 1.19 Å | 1.93 Å | 2.35 Å |

| θ(X-E-X) | 120 ° | 120 ° | 120 ° |

It is clear from the table provided that each molecule has a varying bond length. This is due to changing two variables, the central atom and the ligand. Two ligands are used in these molecules, Hydrogen and Bromine. Hydrogen is the first element in the periodic table and possesses a compact 1s orbital. Due to the compact nature of Hydrogen it is able to be close to the central atom it is bonded to without causing too much steric interference. Bromine on the otherhand is much larger with diffuse p orbitals, and will be required to be further away from the central atom in order to minimise the energy of the molecule. By comparing BH3 and BBr3 it can be seen that the smaller Hydrogen forms a shorter bond than the larger Bromine as expected from the rationale provided. It can also be seen that varying the central atom causes the length of the bond to increase in a molecule. This is evident from comparing BBr3 and GaBr3. Boron is a 2nd row element, giving the atom a small volume. This small volume allows the ligands to form a bond closer to the central atoms. Gallium is a 4th row element causing the atom to have a very large volume. Due to the large volume, the ligands are unable to get as close to Gallium as they had done in Boron, resulting in a bond that is 0.42 Å larger.

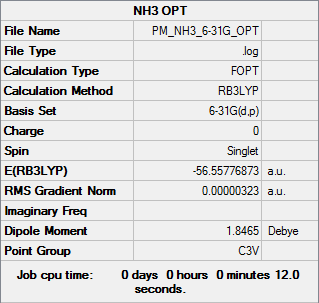

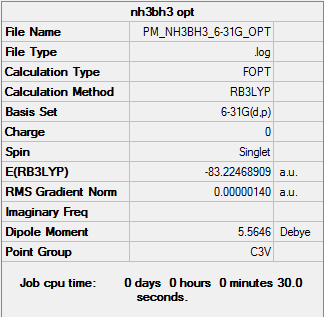

NH3

B3LYP/6-31G(d,p)

Optimisation file DOI:10042/31200

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000006 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000004 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000012 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000008 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-9.844276D-11

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found. |

|

Vibrational Analysis

BH3

B3LYP/6-31G(d,p)

Frequency file DOI:10042/31201

| Summary Data | Low Frequencies |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -3.6016 -1.1356 -0.0055 1.3736 9.7035 9.7697 Low frequencies --- 1162.9825 1213.1733 1213.1760 |

Virbration Spectrum of BH3

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | IR Active | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1163 | 93 | Yes | Bend |

| 1213 | 14 | Yes | Bend |

| 1213 | 14 | Yes | Bend |

| 2583 | 0 | No | Stretch |

| 2716 | 126 | Yes | Stretch |

| 2716 | 126 | Yes | Stretch |

It can be seen from comparing the table and the IR spectrum that not every wavenumber reading is represented as a peak. This can be explained through an understanding of the theory of an IR spectrum.

In order for a vibrational mode in a molecule to be IR active, that is appear as a peak in a spectrum, it must be associated with a change in the dipole moment of the molecule.[1] It can therefore be seen that the vibrations at 1163cm-1, 1213cm-1 and 2716cm-1 induce a dipole change in the BH3 molecule and so record a peak in the provided spectrum.

GaBr3

B3LYP/6-31G(d,p)

Frequency file DOI:10042/31186

| Summary Data | Low Frequencies |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -1.4878 -0.0015 -0.0002 0.0096 0.6540 0.6540 Low frequencies --- 76.3920 76.3924 99.6767 |

Virbration Spectrum of GaBr3

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | IR Active | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 76 | 3 | Weak | Bend |

| 76 | 3 | Weak | Bend |

| 100 | 9 | Weak | Bend |

| 197 | 0 | No | Stretch |

| 316 | 57 | Yes | Stretch |

| 316 | 57 | Yes | Stretch |

By examining the wavenumbers obtained in BH3 and GaBr3 a stark contrast can be seen. This contract can be explained through an understanding of the theory behind IR spectroscopy.

The frequency obtained is defined by a set equation shown below.

This equation has two variables, the force constant and the reduced mass. The force constant examines the strength of the bond; as BH3 has a shorter bond than GaBr3 it is also a stronger bond. Because this bond is stronger the value of the force constant is greater and so contributes to the frequency to be larger. The reduced mass is dependent on the masses of the individual atoms in the molecule. BH3, as a lighter molecule, will have a smaller reduced mass. This smaller value will contribute again to a larger frequency when compared to GaBr3. The combination of these two effects causing the great variation in frequency obtained for the two molecules in question.

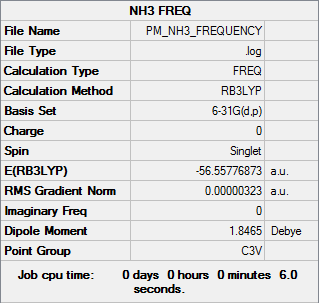

NH3

B3LYP/6-31G(d,p)

Frequency file DOI:10042/31202

| Summary Data | Low Frequencies |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -0.0128 -0.0021 0.0018 7.0724 8.1020 8.1023 Low frequencies --- 1089.3849 1693.9369 1693.9369 |

Virbration Spectrum of NH3

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | IR Active | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1089 | 145 | Yes | Bend |

| 1694 | 14 | Yes | Bend |

| 1694 | 14 | Yes | Bend |

| 3461 | 1 | No | Stretch |

| 3590 | 0 | No | Stretch |

| 3590 | 0 | No | Stretch |

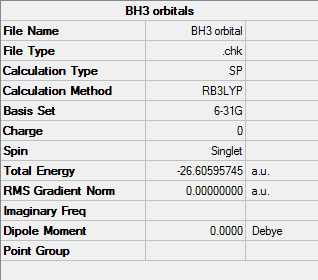

Molecular Orbitals

BH3

B3LYP/6-31G

Orbital file DOI:10042/31187

| Summary Data |

|---|

|

By opening the .chk file produced from the optimisation of BH3, the first 15 molecular orbitals can be calculated, quantified and visualised. However only the first 8 orbitals shall be presented, as the energies of the remaining 7 are too large to be considered viable for the molecule in question.

Molecular Orbital Diagram

Produced above is the MO diagram for BH3 with the predicted molecular orbitals using Linear Combination of Atomic Orbital Theory on the right hand side of the diagram, and the calculated molecular orbitals on the left hand side of the diagram. By comparing theory and experimentation, it can be seen that the molecular orbitals produced are not exactly the same. While they both have obtained the same pattern of orbitals, the extent at which they are spread is difficult to predict from LCAO. As a result of this the possibility of orbitals overlapping, and therefore allowing constructive or destructive interference to take place, is nonexistent causing discrepancies between the two results.

However the LCAO does an incredible job of predicting the general shape of a molecular orbital to a high level of accuracy using only basic principles and assumptions. This makes LCAO a very useful tool to use before running lengthy calculations on larger molecules.

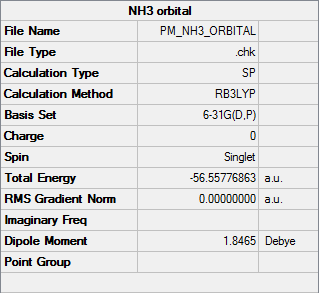

NH3

B3LYP/6-31G(d,p)

Orbital file DOI:10042/31203

| Summary Data |

|---|

|

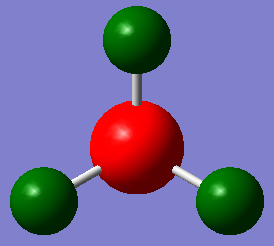

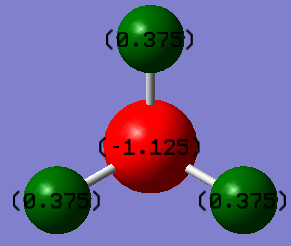

NBO

The following pictures use a charge range of -1 to +1.

| Charge Distribution | NBO charges |

|---|---|

|

|

It can be seen that the NBO charges in an ammonia molecule are +0.375 for Hydrogen and -1.125 for Nitrogen showing the electronegative nature of the Nitrogen atom and overall dipole moment of the molecule.

Association energy of NH3BH3

Optimisation

Optimisation log DOI:10042/31204

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000006 0.000015 YES

RMS Force 0.000002 0.000010 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000036 0.000060 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000016 0.000040 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-2.398179D-10

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found. |

|

Vibrational Analysis

Frequency file DOI:10042/31205

| Summary Data | Low Frequencies |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -5.2939 -2.4930 -2.4798 -0.0008 0.0217 0.1745 Low frequencies --- 263.3094 633.0320 638.4679 |

Virbration Spectrum

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | IR Active | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 263 | 0 | No | Bend |

| 633 | 14 | Yes | Stretch |

| 638 | 4 | Very Weak | Bend |

| 638 | 4 | Very Weak | Bend |

| 1069 | 41 | Yes | Bend |

| 1069 | 41 | Yes | Bend |

| 1196 | 109 | Yes | Bend |

| 1204 | 3 | Very Weak | Bend |

| 1204 | 3 | Very Weak | Bend |

| 1329 | 114 | Yes | Bend |

| 1676 | 28 | Yes | Bend |

| 1676 | 28 | Yes | Bend |

| 2472 | 67 | Yes | Stretch |

| 2532 | 231 | Yes | Stretch |

| 2532 | 231 | Yes | Stretch |

| 3464 | 3 | Very Weak | Stretch |

| 3581 | 28 | Yes | Stretch |

| 3581 | 28 | Yes | Stretch |

Calculating the association energy

The following results are a collection of the B3LYP/6-31G energy of each molecule recorded in au (Hartree)

| Molecule | Energy (au) |

|---|---|

| BH3 | -26.61532363 |

| NH3 | -56.55776873 |

| NH3BH3 | -83.22468909 |

From using these values the energy of association is found to equal 0.05159673 au. Where 1 Hartree = 2625 kJmol-1 the energy of association is therefore 135 kJmol-1 This energy of association is comparable to that of a weak bond.

Questions

What is a bond?

A chemical bond is the attraction of atoms to each other through sharing of electrons. A bond results in a stable molecule only if the total energy of the compound has lower energy than the separated atoms.

How much energy is there in a strong, medium and weak bond? Give examples of each type of bond (strong, medium and weak)

A weak bond is typically around 150 kJmol-1 (I-I), a medium bond around 400 kJmol-1 (C-F), and a strong bond is around 900 kJmol-1 (N-N triple bond)

In some structures gaussview does not draw in the bonds where we expect, why does this NOT mean there is no bond?

Gaussview draws bonds based on a particular predetermined distance. The absence of a drawn bond does not mean that it doesnt exist, it only means that the distance between the atoms has exceeded the predetermined value of a bond programmed into gaussview. Due to the wide variety of molecule in existance it is impossible to produce correct values for a bond to be drawn and so there is likely to be some instances without bonds

Why must you use the same method and basis set for both the optimisation and frequency analysis calculations?

When performing calculations it is vital to use the same method and basis set. The method can be though of as the "LCAO" part of an equation, while the basis set contains all of the functions used. If one combination is used for optimisation and another for frequency then the resulting values will be of no significance.

What is the purpose of carrying out a frequency analysis?

When carrying out a frequency analysis we are finding the derivative of the optimised structure; or the second derivative of the potential energy surface. By performing a second derivative we are able to find out if the stationary points obtained from optimising the structure as a minimum or a maximum. If the frequencies are positive then a minimum has been obtained, if they are negative a maximum has been obtained. If the values are all negative it shows us that our optimisation is not the lowest energy state of the molecule and will have to be redone.

What do the "Low frequencies" represent?

In order to find the number of vibrational modes in a molecule the equation "3N-6" is used where N = Number of atoms. The low frequencies that are presented represent the "-6" part of the equation. These 6 frequencies are the motion of the centre of mass of the molecule and are always much smaller than the first vibration listed.

Project section - Lewis acids and bases

The elements of group 3 can be considered quite unique given the structure that their compounds are able to adopt. Each member possesses only 3 eletrons in its outer most shell, and once bonded to three other atoms, 6. By possessing only 6 electrons the stability associated with forming an octet is not satisfied, resulting in a highly lewis acidic molecule. To overcome this instability, the species can dimerise using bridging halogens, gaining an extra two electrons from a dative bond, forming an octet, and therefore a stable species. This project will investigate the conformers and vibrations of Al2Cl4Br2 and the MO of the lowest energy form with in depth analysis and discussion.

Isomers and Symmetry

Due to the different physical arrangement of the atoms in each isomer, each point group must be found and imposed when performing each calculation. The five possible isomers are shown below.

| Isomer 1 | Isomer 2 | Isomer 3 | Isomer 4 | Isomer 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| D2h | C2v | C2v | C2h | C1 |

Isomer 5 is capable to exist as one of two non-superposable enantiomers. From calculations on gaussview it was clear however that the energies of the two enantiomers are indistinguishable from each other. For convenience only the shown enantiomer of isomer 5 will be used in calculations.

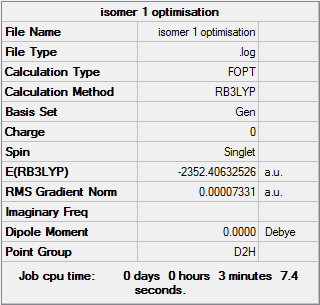

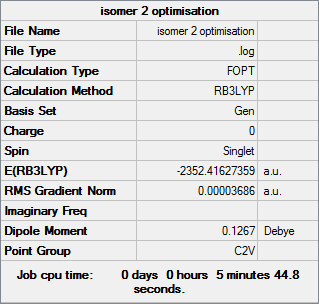

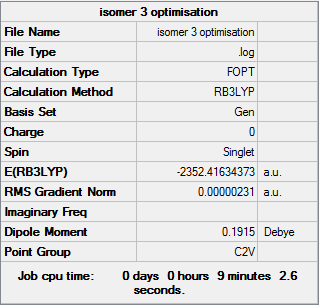

Optimisation

Each isomer of Al2Cl4Br2 was optimised using a 6-31G(d,p) basis set for the Al and Cl atoms, while Br was optimised using a psuedopotential. On top of this each isomer had its molecular symmetry imposed to produce more accurate readings. The results of the optimisations are desplayed below.

Isomer 1

Optimisation file DOI:10042/31282

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000130 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000047 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000333 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000148 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-5.339204D-08

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found. |

|

Isomer 2

Optimisation file DOI:10042/31283

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000073 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000039 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.001704 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000766 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.959833D-07

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found. |

|

Isomer 3

Optimisation file DOI:10042/31284

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000008 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000002 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000039 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000017 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-4.545969D-10

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found. |

|

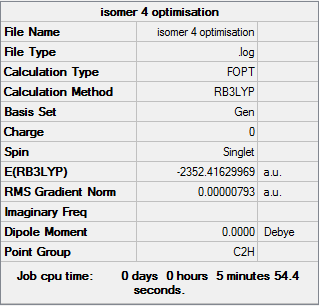

Isomer 4

Optimisation file DOI:10042/31285

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000011 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000005 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000111 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000039 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-2.840505D-09

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found. |

|

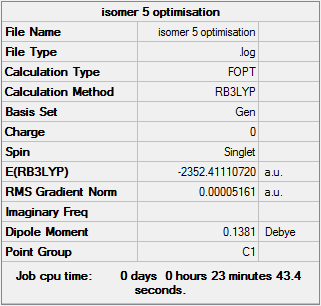

Isomer 5

Optimisation file DOI:10042/31286

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000113 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000030 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000975 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000357 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-6.361190D-08

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found. |

|

It can be seen from the Item tables that maximum and RMS values of Force and Displacement have all converged. As the results are converging gaussview has calculated that the gradient of the potential energy curve of the isomer is equal to zero. It does not however tell us if the result obtained is equal to a maximum or a minimum. This can only be calculated by finding the second derivative of the potential energy curve, corresponding to a frequency analysis.

Frequency Analysis

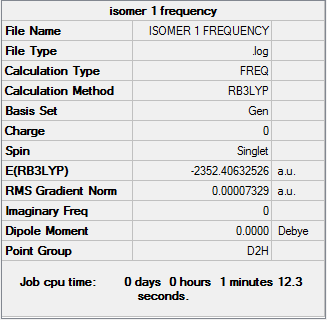

Isomer 1

Frequency file DOI:10042/31288

| Summary Data | Low Frequencies |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -1.1397 0.0028 0.0035 0.0036 3.0016 3.5512 Low frequencies --- 16.4839 63.8293 86.1948 |

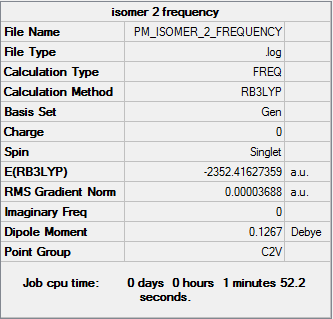

Isomer 2

Frequency file DOI:10042/31321

| Summary Data | Low Frequencies |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -1.5326 -1.3970 -0.0019 -0.0016 0.0028 0.7419 Low frequencies --- 17.4259 51.3210 78.3261 |

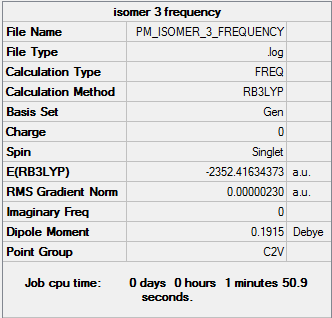

Isomer 3

Frequency file DOI:10042/31290

| Summary Data | Low Frequencies |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -0.7556 -0.7526 -0.0036 -0.0025 -0.0021 2.0815 Low frequencies --- 18.6348 51.2163 72.2020 |

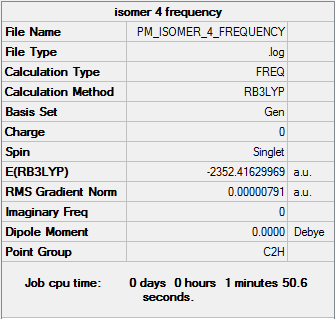

Isomer 4

Frequency file DOI:10042/31291

| Summary Data | Low Frequencies |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -1.8609 -1.5358 -0.9469 -0.0041 -0.0027 -0.0006 Low frequencies --- 18.1962 49.1619 72.8933 |

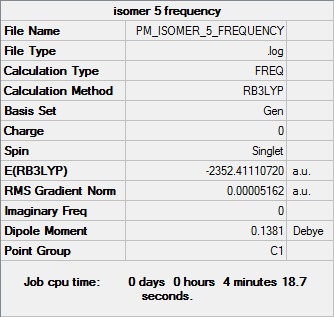

Isomer 5

Frequency file DOI:10042/31292

| Summary Data | Low Frequencies |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -0.3665 0.0016 0.0017 0.0020 1.6694 2.2983 Low frequencies --- 16.9866 55.9273 80.0556 |

By examining the frequencies given we can find out if a minimum energy was obtained in our optimisation. By taking the second derivative was are revealing the nature of the stationary point found. If all the frequencies on the second line are positive, a minimum has been found, while if they are negative a maximum has been found. It can be seen from the frequency section that all the values for each isomer are positive, confirming we have obtained a minimum energy optimisation. By examining the first line of low frequencies the accuracy of our calculations can be found. In general the closer the numbers are to zero, either positive or negative, the greater the accuracy of the calculation performed. As all the values are within ±4cm-1 it can be said that our readings are accurate to a high degree.

Discussion

It can be seen from the IR spectrum that the symmetry of the molecule affects the total number of bands produced. Molecules with a low symmetry tend to have the most amount of peaks, while highly symmetrical molecules tend to have the least amount of peaks. This can be seen by comparing isomer 5 and isomer 1. Isomer 5 has C1 symmetry corresponding to only one symmetry operation: E. This low symmetry is reflected in the IR spectrum produced. Isomer 1 has D2h symmetry and therefore possesses 8 symmetry operations. Due to this symmetrical nature the molecule produces less peaks in its IR spectrum.

The number of vibrational nodes that a molecule can possess is bound by the equation 3N-6 where N = number of atoms. [3] For each of these molecules it would be expected that 18 peaks would be observed in the IR spectra. This is clearly not the case in all the isomers observed. This can be rationalised, an IR peak is only observed if the related vibration results in a change in the dipole moment of the molecule, and hence the total number of peaks is substantially less than calculated.

The position of the Br atoms relative to Al causes variation in the vibrational frequencies observed. The following table compares the bridging area of the dimer.

| Isomer | Vibration Image | Frequency (cm-1) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

341.63 |

| 2 |  |

412.80 |

| 3 |  |

413.02 |

| 4 |  |

412.94 |

| 5 |  |

384.40 |

By producing vibrations that are similar in each molecule a comparison can be made between them about the effects of bridging atoms.

It is shown that when both bridging atoms are Cl the frequency observed is roughly equal to 413cm-1 regardless of the position of the Br atoms. Where one atom is Br the frequency is 384.40cm-1 and where both atoms are Br the frequency is 341.63cm-1. These values can be explained from the equation provided in section 1.6.2.2.

From solely using the equation provided it can be predicted that the molecules with bridging Cl atoms would be the highest in frequence observed. This is due to two reasons, the first being the reduced mass of the bridge. The combination of two Cl atoms produces the lowest possible reduced mass available from the selection of Br and Cl atoms. The second reason is from the force constant of the Al-Cl bond. While the exact value for the force constant is unknown, it is known that the bond enthalpy is proportional to k. As the strength of an Al-Cl bond is equal to 502 kJmol-1 and the strength of an Al-Br bond equaling 429.2 kJmol-1 [4] it can be concluded that Al-Cl will have the largest force constant.

The combination of a low reduced mass and a large force constant would result in all isomers with purely bridging Cl atoms to have the largest observed frequency, which is observed in the computation provided.

Using the same reasoning it can be said that the combination of two bridging Br atoms would result in the smallest observed frequency, while a combination of both atoms results in a frequency set between the two, both of which are found to be true.

Next I compared the effect of terminal atom arrangements.

| Isomer | Vibration Image | Frequency (cm-1) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

616.82 |

| 2 |  |

582.85 |

| 3 |  |

495.37 |

| 4 |  |

579.54 |

| 5 |  |

574.47 |

Again a series of vibrations were analysised that were similar in pattern. This was more difficult than the previous to achieve due to the great variation present in the vibrational modes.

Initial examination shows that the Br atoms have no vibrations associated with these modes in any of the isomers examined. This is likely to result from the much greater mass present in Br than in Al or Cl.

Isomer 1, containing four bridging Cl atoms, produced the largest frequency, as expected due to strength of the Cl bonds and the reduced mass obtained.

Isomers 2 and 4 produce vibrations consisting only of Al and terminal Cl components. Due to the reduced number of components the frequency equation would therefore effectively only use 2 Al atoms and 2 Cl atoms, ignoring the Br presence, resulting in a value similar to isomer 1.

From examination of the displacement arrows it can be seen that in isomers 3 and 5 one of the Al atoms has no vibrational mode present. This occurs on an Al atom if it is connected to both Br atoms.

Stability of isomers

Each of the five isomers vary in their total energy. This is due to the positioning of the Chlorine and Bromine atoms relative to each other. The table below shows the energy and relative energy of each isomer to the lowest energy conformer.

| Isomer | Energy (au) | Relative energy (au) | Relative energy (kJmol-1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | -2352.40632526 | 0.01001847 | 26.29848375 |

| 2 | -2352.41627359 | 0.00007014 | 0.18411750 |

| 3 | -2352.41634373 | 0.00000000 | 0 |

| 4 | -2352.41629969 | 0.00004404 | 0.11560500 |

| 5 | -2352.41110720 | 0.00523653 | 13.74589125 |

From the table produced there is a distinct order of stability for each of the five isomers. This ordering, from most stable to least stable is 3>4>2>5>1. Bridging atoms in general are weaker than their non-bridging counterparts. As they are part of a 3c-2e system the bond order for each interaction will be 0.5 [5]. A decrease in bond order results in elongation and weakening when compared to a usual bond order of 1. This can be seen in the Jmol diagrams provided in section 2.2, where the length increases by roughly 0.02 Å. As mentioned in section 2.3.6 the energy of the Al-Br bond is less than that of Al-Cl. Because of this inherently weak bond any molecules that use Br atoms to bridge will be unstable compared to the lowest energy conformer. This is reflected in the energies of isomer 1 and 5 which are several times higher than the other isomers. Isomer 1, containing two bridging Br atoms, is twice as unstable than isomer 5, which contains one bridging Br atom and one bridging Cl atom.

Isomer 2 and 4 are quite similar in energy as they are cis/trans isomers of each other. Isomer 4 is the lowest energy of the pair due to its trans conformation. By existing in the trans form this isomer has removed the unfavoured steric clashing associated with having two large Br atoms occupying the same area of space in the molecule.

Isomer 3 is the most stable of form of Al2Cl4Br2. While at first this may not seem the case due to two large Br atoms attached to the same Al atom it must be remembered that the centre is sp3 hybridised. This hydridisation places each atom at 109.5 ° away from each other, and when combined with the length of an Al-Br bond, results in a stable isomer.

Dissociation energy

Due to the presence of bridging halogens, the formation of a dimer results in the release of energy. This energy can be calculated by finding the difference between the product and the monomers. Isomer 3 is the lowest energy conformer and is unique. It is the only conformer where the monomers can be two different combinations. One group would consist of AlCl3 and AlClBr2. The other group can form from two AlCl2Br monomers by rearranging during the dissociation process. Both of these groups of monomers shall be probed and the kinetic and thermodynamic effects disscussed.

In order to calculate the energy, each of the monomers must be optimised and a frequency analysis performed.

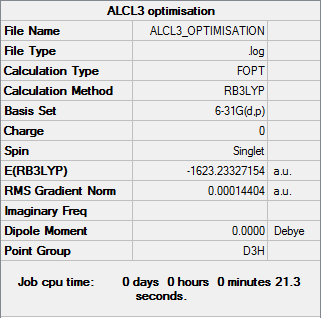

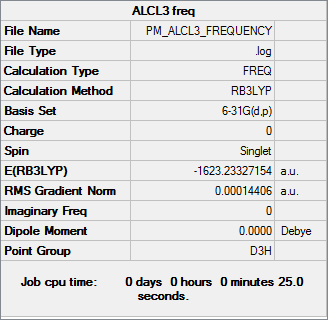

AlCl3

Optimisation

Optimisation file DOI:10042/31310

| Summary Data | Convergence |

|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000288 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000189 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.001528 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.001000 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-7.413653D-07

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

Frequency analysis

Frequency file DOI:10042/31311

| Summary Data | Low Frequencies |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -7.0287 -6.6294 -6.6294 -0.0031 0.0111 0.0550 Low frequencies --- 147.1595 147.1611 197.9846 |

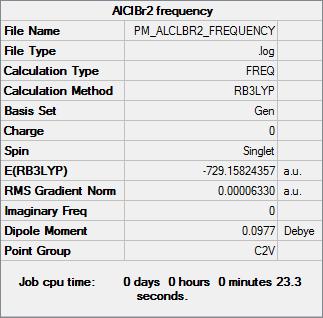

AlClBr2

Optimisation

Optimisation file DOI:10042/31322

| Summary Data | Convergence |

|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000092 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000060 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000553 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000300 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-6.831864D-08

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

Frequency analysis

Frequency file DOI:10042/31323

| Summary Data | Low Frequencies |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -1.9604 -1.3907 -1.1444 -0.0018 0.0015 0.0016 Low frequencies --- 98.2500 118.2767 173.4424 |

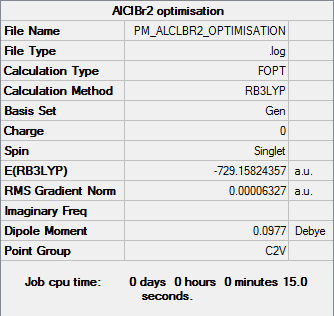

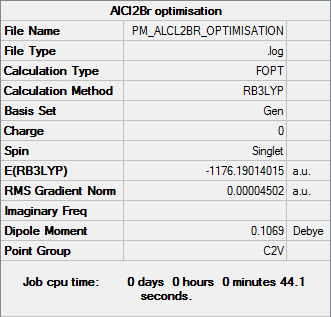

AlCl2Br

Optimisation

Optimisation file DOI:10042/31328

| Summary Data | Convergence |

|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000149 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000078 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000751 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000541 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-9.241448D-08

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

Frequency analysis

Frequency file DOI:10042/31329

| Summary Data | Low Frequencies |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -0.0039 0.0007 0.0011 3.3756 3.6552 4.1209 Low frequencies --- 120.7185 133.9343 185.8750 |

Results

| Monomer | Energy (au) |

|---|---|

| AlCl3 | -1623.23327154 |

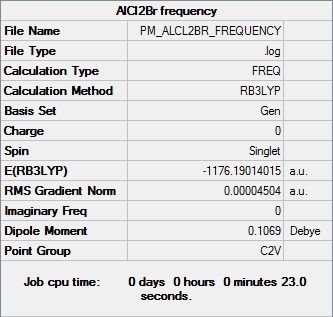

| AlCl2Br | -1176.19014015 |

| AlClBr2 | -729.15824357 |

Using these results and the energy of isomer 3, the dissociation energy relating to the two groups of monomers can be found.

For the first possible group consisting of one monomer of AlCl3 and AlClBr2 the energy is found to be:

(-2352.41634373) - (-1623.23327154 + -729.15824357) = -0.02482862 au = -65.1751275 kJmol-1

For the second possible group consisting of two monomers of AlCl2Br:

(-2352.41634373) - (-1176.19014015 * 2) = -0.03606343 au = -94.66650375 kJmol-1

In both cases it is clear that the product formed is more stable than its constituent monomers. From examining the energies it is also possible to determine which group of monomers will likely be formed from the dissociation of isomer 3. The second group has the most negative energy value and telling us that it is the thermodynamic product. Whether this is the major product however is unclear. To form these monomers the molecule must undertake a rearrangement of atoms which has its own kinetic barrier. Due to this kinetic barrier it is more likely that the monomers of the first group would be formed, however without experimental results this conclusion is hypothetical.

Orbitals

To obtain a better understanding of the nature of the bonds present, a molecular orbital analysis was performed on isomer 3. Initially all orbitals were modelled and viewed, however due to the extremely deep energy of the core orbitals (ranging from -2 to -101 au), their effects shall not be considered for this discussion.

A series of molecular orbitals (MOs) ranging from highly antibonding to highly bonding have been selected to be discussed below.

MO 39

1 and 2. Nodal planes of the bridging and terminal Cl atoms respectively. As there is only one nodal plane present in each of these orbitals it can be concluded that they are p orbitals.

3. Strong through-space antibonding π* orbital formed from the out of phase overlap between the p orbitals of the bridging Cl atoms.

4. Strong through-space bonding interaction between the p orbitals of the bridging Cl atoms and the orthogonal p orbitals of the terminal Cl atoms. This bonding can be seen as "π like" due to the overlap of p orbitals and results in a partial double bond character. However this double bond would not be observed as the "π* orbital" is also filled, negating any characteristics such as reduced bond length.

5. Non contributing Al atoms and terminal Br atoms.

MO 40

1 and 2. Nodal planes of the bridging and terminal atoms of the molecule respectively. As there is only one nodal plane per atom present it can be concluded they are p orbitals.

3. Strong through-space bonding π orbital formed from the in phase overlap of the bridging Cl p orbitals and each of the terminal p orbitals.

4. Weak through-space bonding interaction between a terminal Br p orbital and a terminal Cl p orbital.

5. Medium through-space antibonding interaction between the p orbitals of identical terminal atoms (Br and Br, Cl and Cl).

6. Weak through-space antibonding interaction between the outside lobe of the p orbital of the terminal atoms, and the p orbital of the bridging Cl atoms.

7. Non contributing Al atoms.

MO 51

1 and 2. Nodal planes of the terminal Br atoms and bridging Cl atoms respectively. As there is only one nodal plane per atom mentioned it can be concluded they are p orbitals.

3. Due to the Br-Al-Br angle the p orbitals of the terminal Br atoms are pushed together in such a way that the original through-space bonding interaction of the outside lobe becomes a "π like" orbital. Conversely the inside lobes of the p orbitals are pushed away from each other, causing an originally strong through-space bonding interaction to become a weak interaction.

4. Medium through-space bonding interaction between the bridging Cl p orbitals.

5. Strong through-space antibonding interaction between the p orbital of the bridging Cl atoms and the p orbital of the terminal Br atoms.

6. Medium through-space bonding interaction between the p orbital of the bridging Cl atoms and the p orbital of the terminal Br atoms.

7. Non contributing Al atoms and terminal Cl atoms.

MO 52

1, 2 and 3. Nodal planes of the terminal Br atoms, terminal Cl atoms, and the bridging Cl atoms respectively. As there is only one nodal plane per atom mentioned it can be concluded they are p orbitals.

4. Strong through-space bonding π orbital formed from the in phase overlap of the p orbitals of the terminal Br atoms.

5. Strong through-space antibonding interaction between Br π system and the orthogonal bridging Cl p orbitals.

6. Weak through-space antibonding interaction between the bridging Cl p orbitals and the orthogonal terminal Cl p orbitals.

7. Weak through-space bonding interaction between the terminal Cl p orbitals.

8. Weak through-space antibonding interaction between the bridging Cl p orbitals.

9. Non contributing Al atoms.

MO 53

1 and 2. Nodal planes of the terminal Br atoms and the bridging Cl atoms respectively. As there is only one nodal plane per atom mentioned it can be concluded they are p orbitals.

3. Strong through-space antibonding π* orbital formed from the out of phase overlap between the p orbitals of the terminal Br atoms.

4. Strong through-space antibonding interaction between the terminal Br p orbitals and the orthogonal bridging Cl p orbitals.

5. Medium through-space antibonding interaction between the terminal Br p orbitals and the orthogonal brdiging Cl p orbitals.

6. Non contributing Al atoms.

References

- ↑ Paula, Peter Atkins, Julio de (2009). Elements of physical chemistry (5th ed. ed.). Oxford: Oxford U.P. p. 459.

- ↑ Infrared Spectroscopy: Fundamentals and Applications by Barbara Atuart, John Wiley&Sons, Ltd., 2004.

- ↑ Landau, L. D.; Lifshitz, E. M. (1976). Mechanics (3rd ed.). Pergamon Press

- ↑ Luo, Y. R. Comprehensive Handbook of Chemical Bond Energies, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, 2007

- ↑ F. Albert Cotton, Geoffrey Wilkinson and Paul L. Gaus, Basic Inorganic Chemistry, 2nd ed. (Wiley 1987), p.113