Rep:Mod:pkm02

Computational Lab: Module 2

Introduction

BH3 analysis

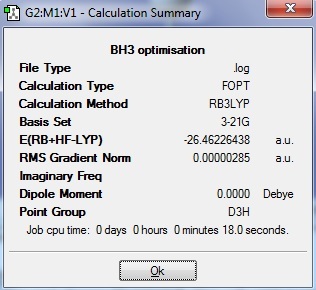

RB3LYP method and 3-21G basis set were used to optimise BH3. During the optimisation calculation, the nuclei were moved and at each position the Schrödinger equation was solved to simulate the electronic density and energy until the lowest energy is found, which is the desired, optimised geometry, i.e. the most stable configuration.

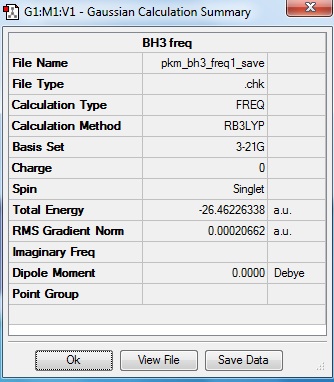

The optimised BH3 result is shown in figure 1 below.

The optimised BH3 has energy of -26.46 a.u., with the B-H bond length of 1.19 Å[1], and H-B-H bond angle as 120o[2]. These results match the literature values. The overall dipole moment of the molecule is 0 debye and the point group of BH3 is D3h.

The graph of total energy vs optimisation step number shows a gradual decrease in energy of the molecule as the calculation proceeded, i.e. the molecule becomes more stable as it is optimised. The other graph of RMS gradient vs optimisation obtained from the optimisation shows that Root Mean Square (RMS) gradient is indeed very close to zero meaning that the minimum stable point was found, i.e. the optimisation was successful. RMS gradient is the derivative of energy with respect to the distance between atoms, and hence a turning point is found if it is zero.

NBO analysis

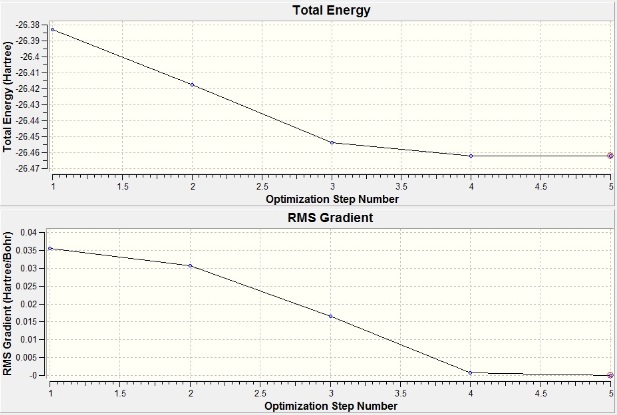

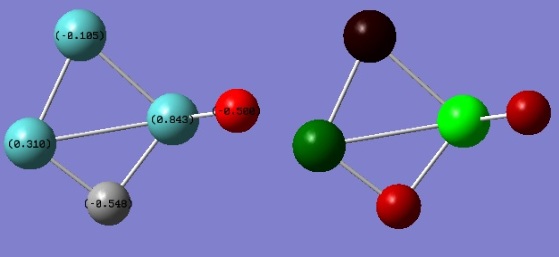

The charge distribution of BH3 was examined.

The colours shown on the above diagram are indication of natural charges. Bright green corresponds to highly positive charge region whereas dark red corresponds to highly negative charge region.

This is in good agreement with prediction since boron atom is Lewis deficient and is therefore highly positive charged.

The numbers on the diagram is another indication of natural charges of regions, where positive number corresponds to positive region and negative numbers correspond to negative region.

The sum of the negative charge values contributed from the hydrogen atoms equals the charge value of the boron atom. This means that this molecule has no overall dipole moment, which is confirmed by the calculation shown in the summary table (Figure 2) that BH3 has an overall dipole moment of 0 debye.

NBO analysis is a useful tool to determine the hybridisation of a molecule. From the "Bond orbital/ Coefficients/ Hybrids" section in the output log file, it shows that B has 33% of s character and 66% of p character, i.e. BH3 is sp2 hybridised, which again matches well with what we expect since BH3 is a planar sp2 molecule.

MO analysis

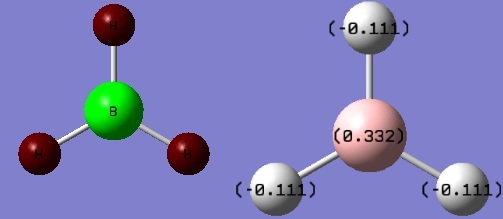

After optimising the geometry of BH3, the checkpoint file was loaded in Gaussview 03 and the calculation setting was adjusted to generate a new input file which was then run over HPC for generating MOs.

MO of BH3: DOI:10042/to-5749

This diagram shows the orbital window after the job was run. Orbitals 1-8 were generated where orbitals 1-4 were filled and 5-8 were empty.

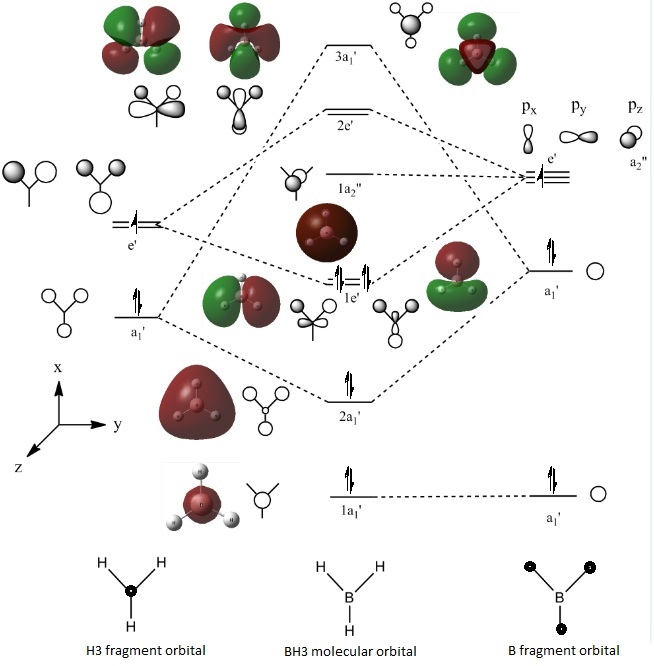

The computed molecular orbitals were compared with those derived from the Linear Combination of Atomic Orbitals approach of BH3.

From figure 4, the shapes of the computed orbitals match very well with those derived. This shows that computational chemistry is a powerful tool for prediction.

Vibrational analysis

Frequency analysis was carried out after optimisation to confirm that the optimisation is indeed successful. A zero gradient only indicates a turning point and that could either be a minimum or a maximum. Therefore in order to prove that it is a minimum point, a second derivative has to be taken, which is the frequency analysis. Only if all the frequencies are positive then we can be sure that we have a minimum.

The summary of vibrational frequency analysis of BH3 is shown below.

The total energy shown above is very similar to that generated from optimisation, i.e. the frequency analysis was carried out on the correct optimised BH3 file.

Animating the vibrations

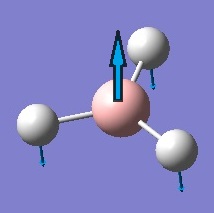

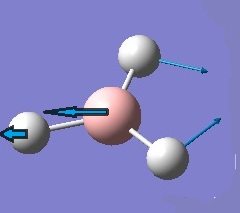

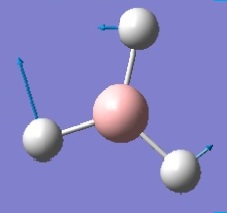

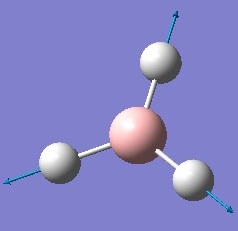

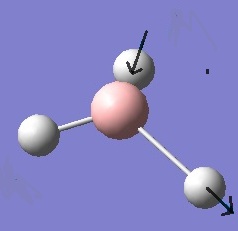

From the frequency analysis, 6 vibration modes were generated. This meets our prediction since BH3 is a non- linear molecule and for a non- linear molecule, the number of vibrational modes can be found using the equation (3N-6) where N is the number of atoms in the molecule. BH3 comprises of 4 atoms and therefore (3 x 4 -6)=6 yielding 6 vibration modes.

| Number | Mode of Vibration | Form of Vibration | Description | Frequency cm-1 | Literature frequency cm-1[3] | Intensity | Symmetry Point Group |

| 1 |  |

Out-of-Plane Wagging | The three hydrogen atoms move with the same amplitude against the more gentle vibration of the boron atom. | 1144 | 1147 | 93 | A2 |

| 2 |  |

In-plane Scissoring | Two hydrogen atoms move towards each other in one direction like a scissors while the other hydrogen and boron atoms move in the opposite direction gently. | 1204 | 1197 | 12 | E' |

| 3 |  |

In-plane Rocking | Movement of the hydrogen atoms in the BH3 plane. | 1204 | 1197 | 12 | E' |

| 4 |  |

Symmetric Stretch | Movement of the hydrogen atoms like a breathing mode in the BH3 plane while the boron atom has its position fixed. | 2598 | 2502 | 0 | A1' |

| 5 |  |

Asymmetric Stretch | The hydrogen atoms move in the same direction while the other hydrogen remains fixed in position and the boron atom vibrates up and down gently. | 2737 | 2602 | 104 | E' |

| 6 |  |

Asymmetric Stretch | The hydrogen atoms move in the plane of BH3 pointing in the same direction. The of them stretch in and out like breathing mode while the other one moves towards and away from the boron atom. | 2737 | 2602 | 194 | E' |

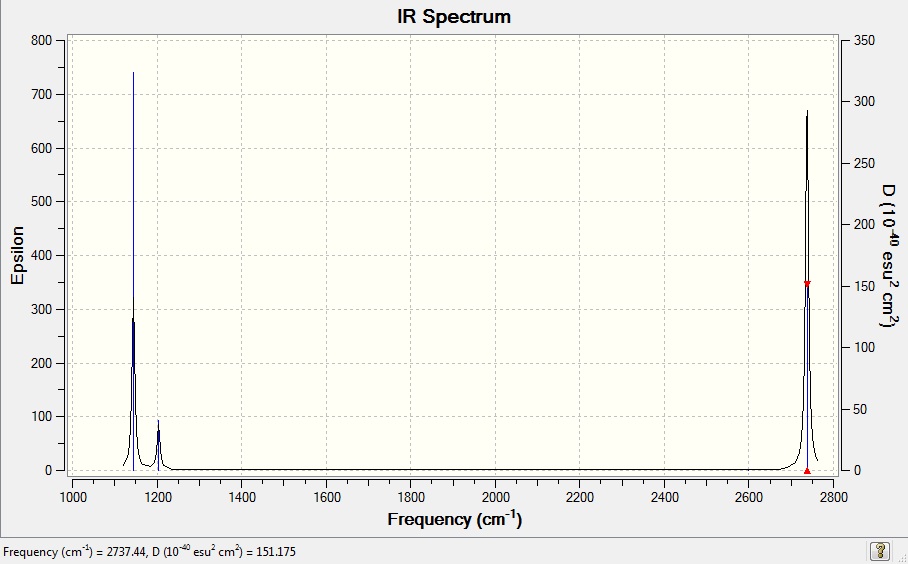

The computed IR is shown below.

The computed IR spectrum indicates clearly that there are only 3 peaks which are observable for BH3, which contradicts with the 6 vibration modes found above. This can be explained by the vibrational movements computed. There are two degenerate sets of vibrations at 1204 and 2737cm-1 .Since they are degenerate, only one of each of the two vibrations will be seen on the spectrum. Besides, no intensity is shown for vibrational mode 4 of BH3, i.e. no infrared is detected for mode 4 and it is infrared inactive. This is because the vibrational movements of H atoms cancel out each other due to symmetry, therefore results in no change in dipole moment. This is confirmed by the result from the summary table in figure 5 that the dipole moment for BH3 is 0 debye.

At higher frequencies, the computed result deviates from literature results by as much as 100cm-1. This shows that computational method is good for computing the number of modes of vibrations,but is less good for reproducing the experimental results quantitatively.

TlBr3 analysis

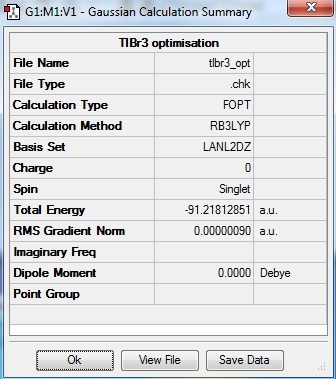

TlBr3 with D3h symmetry was optimised using the calculation type FOPT, calculation method RB3LYP, and a medium level basis set LANL2DZ. This includes a greater number of functions to describe the electronic structure compared to 3-21G basis set used for BH3.

The important information found from the summary table is as follow.

The total energy of the optimised structure is shown to be -91.22 a.u.. The RMS gradient is very close to zero indicating successful optimisation. The dipole moment is 0 debye.

The optimised Tl-Br bond is 2.65Å and the optimised Br-Tl-Br bond angle is 120o. These results show good correlation with the literature values: 2.55Å for Tl-Br bond and 120o Br-Tl-Br bond angle[4].

Optimised TlBr3: DOI:10042/to-5730

The frequency analysis was carried out afterwards and the positive frequencies indicate that the minimum had been found.

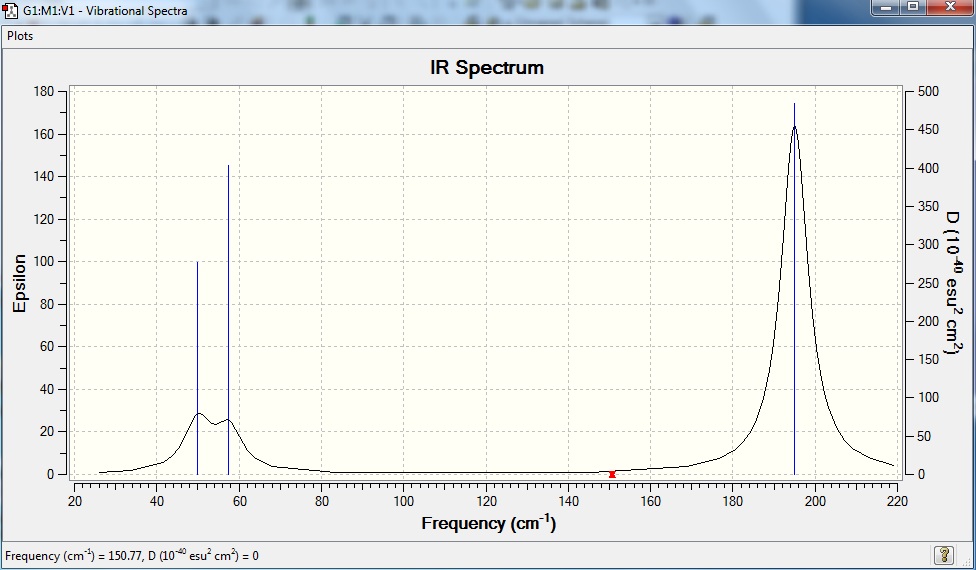

Computed IR of TlBr3 is shown below.

Thallium is a high electron count of 81. To save time in running the computational analysis, it is assumed that the core electrons in an atom do not contribute much to the bonding interactions, and they are modelled by pseudo-potential (PP).

The same method and basis set were used for both calculations so that the results can be compared on the same scale. For comparison to be made, the conditions cannot be different since different methods and levels of basis set will lead to different energies.

As before, frequency analysis has to be carried out after each optimisation in order to confirm that the global minimum point is found. A zero gradient only indicates a turning point and that could either be a minimum (ground state) or a maximum (transition state). Therefore in order to prove that it is a minimum point, a second derivative has to be taken, i.e. the frequency analysis. Only if all the frequencies are positive then we can be convinced that we have a minimum. Frequency analysis can also be used to generate computed infrared frequencies which can then be compared with experimental data.

| Low Frequency /cm-1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 20 | 20 |

| Real Normal Mode Frequency cm-1 | 50 | 50 | 57 | 151 | 195 | 195 |

The lowest real normal mode has a frequency of 50cm-1.

In gaussview, a bond is only drawn when the distance between two atoms are within the set range in the program. If the distance between the atoms is outside this range, the program would not define it as a bond. This does not mean that the bond is not in existence.

A bond is the ionic, dipole, covalent or van der Waals interactions between two atoms which, when comes into contact, bond together and stabilise the overall energy, i.e. with a lower energy than the sum of two individual atoms’ energy. The electron density can either be shared between the two atoms, or when the electron density sits on one atom due to higher electronegativity and the other atom bound to it by electrostatic interaction. For van der Waals, the constant movement of electron cloud would result in temporary change in electron density on either side so the two atoms would bound together through weak electrostatic interaction.

Comparing the results from BH3 and TlBr3, BH3 shows higher vibrational frequency because it has a lower molecular weight than TlBr3 and therefore can be excited to vibrate to a greater extent when given the same amount of energy. The direct proportionality of E=h x f (where E is the energy, h is the Planck constant, and f is the frequency) indicates that more vibrational energy will result in higher vibrational frequency.

Analysis of Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 isomers

The aim of this part is to determine whether the cis or trans isomer is the more stable conformer. Their infrared vibrations were also investigated.

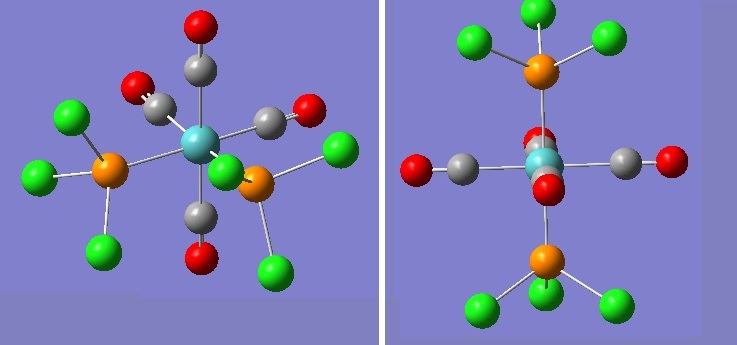

First, the ground state structures of cis- and trans- Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 were optimised using Gaussview05 with the method B3LYP and the basis set LANL2MB. This is a low level basis set which allows us to find the rough geometry very quickly with good enough bond lengths and angles.

This optimised structure was then edited using Gaussview05 where the torsion angles of the PCl3 groups were altered. For the cis isomer, one Cl atom was set to point upwards parallel to the axial bond, whereas one Cl atom on the other group was set to point downwards. For the trans isomer, both PCl3 groups were set to be eclipsed, i.e. one overlap with the other, and also one Cl atom of each PCl3 group was set to be parallel to a Mo-C bond. By changing the orientations, the right minima which have the lowest energy were reached in a short period of time.

These new geometries were than optimised again using the method B3LYP and the basis set LANL2DZ, which is a higher level basis set than LANL2MB leading to higher accuracy.

Frequency analysis was then carried out to confirm that we have found the global minima from the second optimisation. All frequencies for both cis and trans isomers were positive indicating successful optimisation and the minima were found.

Cis isomer after loose optimisation: DOI:10042/to-5731

Trans isomer after loose optimisation: DOI:10042/to-5744

Cis fully optimised frequency analysis: DOI:10042/to-5832

Trans fully optimised frequency analysis: DOI:10042/to-5837

First optimisation of Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 isomers

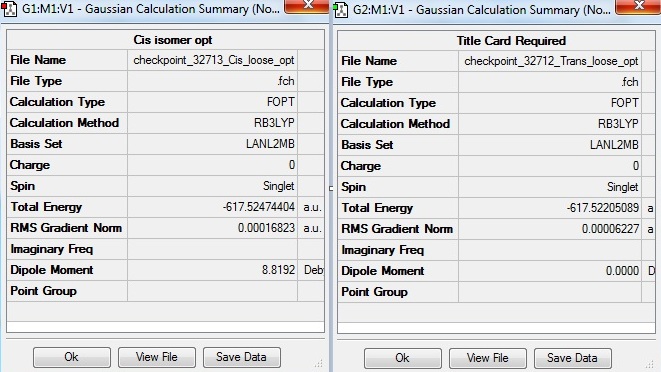

The summary tables shown below were obtained after the first loose optimisation.

The geometric parameters are compared as follow.

The literature values used were for Cr(CO)4(PPh3)2 since no experimental values could be found for Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2. However, it is acceptable to use literature values for Cr(CO)4(PPh3)2 to compare with our results since PPh3 ligand and Cl- ligand both have similar contributions to sterics and electronics of the molecule. Also, Cr is in the same group as Mo, therefore the general trend of reactivity and properties in the group would be similar. Nonetheless PCl3 ligands were used instead of PPh3 in the first place to reduce the computational time. Not all the parameters can be found from literature.

Analysis

The RMS gradient for both cis and trans isomers are close to zero, showing successful optimisation.

The trans isomer has no dipole moment due to symmetrical geometry and all the dipole moments cancel out, whereas the cis isomer has a dipole moment of 8.8 debye.

The cis isomer has slightly lower energy of 8.7kJmol-1 compared to the trans isomer indicating greater stabilility for cis.

Both sterics and electronics contribute to the stability of the isomers. The bulky PCl3 ligands are closer to each other in the cis isomer compared to the trans one where they are further apart from each other. More steric strain is present in the cis isomer and so the energy of the molecule would be raised. However, the trans-effect of CO plays a bigger role in this case. CO is a strong π-acceptor and is high up in the trans effect series. The greater the trans-effect exhibits in the molecule the higher the energy will be. For the cis isomer, there is only one pair of CO being trans to one another and therefore the trans effect is smaller for cis compared to trans, which has two pairs of trans CO. Electronic effect wins out in this case and therefore the more sterically hindered cis isomer is slightly more stable.

Second optimisation of Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 isomers

Even though the computed values from first optimisation are in good match with literature values already, the torsion angles in both structures were altered and then optimised again to ensure the minima are found. An even higher level basis set LANL2DZ was used this time to ensure better description of the electronic structures.

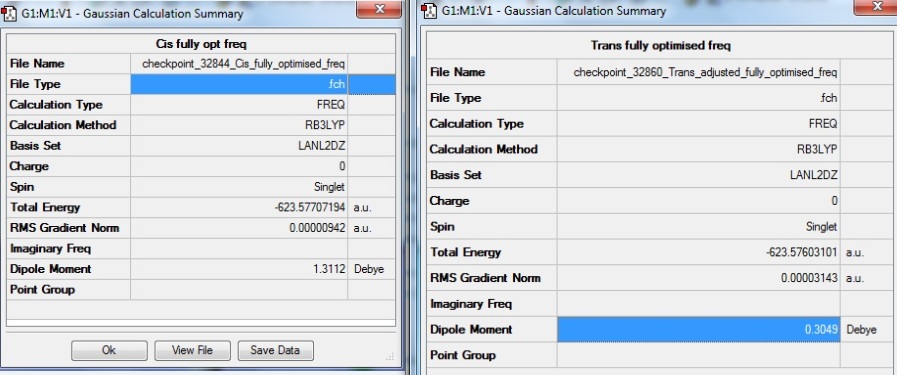

The geometries were edited as described above. The summary tables for the second optimised structures are shown below.

The optimised structures are shown below.

The energies for both isomers were lowered further by 6 hartree a.u. after the second optimisation. The RMS gradient values were even closer to zero indicating that the minima were reached. The cis isomer is now 4.3 kJmol-1 lower in energy than the trans one, compared to the difference of 8.7kJmol-1 after the first optimisation.

The dipole moment for trans isomer increased from 0 to 0.3 debye after the optimisation. This means that the alteration reduced the symmetry of trans isomer slightly and therefore the dipole movements do not cancel out each other fully. Whereas for cis isomer, the alteration raised the symmetry of the geometry and led to a significant decrease in dipole moment down from 8.8 to 1.3debye.

The comparisons are tabulated below.

Bond lengths and angles comparison of trans-isomer to literature value

| Trans Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 | Literature value [5] Trans Cr(CO)4(PPh3)2 | |

| Average Mo-P bond length / Å | 2.44 | 2.36 |

| Average Mo-C bond length / Å | 2.06 | 1.87 |

| P-Mo-P bond angle/ ° | 177.4 | 176.7 |

| P-Mo-C bond angle / ° | 88.7 | 89.5 |

Bond lengths and angles comparison of cis-isomer to literature value

| Cis Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 | Literature value [6] Cis Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2 | |

| Average P-Mo bond length / Å | 2.51 | 2.58 |

| Average Mo-C bond length / Å | 2.01 | 2.04 |

| P-Mo-P bond angle / ° | 94.2 | 104.6 |

| P-Mo-C (trans to P) bond angle / ° | 176.1 | 163.7 |

| P-Mo-C (cis to P) bond angle/ ° | 89.2 | 80.6 |

The computed values from second optimisation are in an even closer match with the literature values than the ones from first optimisation. This shows that the slight alteration to the structures led to more stable better optimised structures.

The computed bond lengths and angles match well with the literature values. However, deviations are inevitable and quantitative comparison cannot be made since the literature values used was not for the exact molecules which were computed. They were only used to check if the computed results were within a reasonable range.

By changing the PCl3 ligands on the isomers, the stability of the isomers can be reversed. For example, if the trans- effect present in the trans isomer is lowered, then the steric effect would become the primary factor for destabilising the molecule and raising the energy of cis isomer since steric strain would be higher in cis form.

CN- ligands can be introduced to replace Cl- ligands since CN- exhibits greater trans-effect compared to CO ligands. This could have an effect of reversing the stability of the isomers.

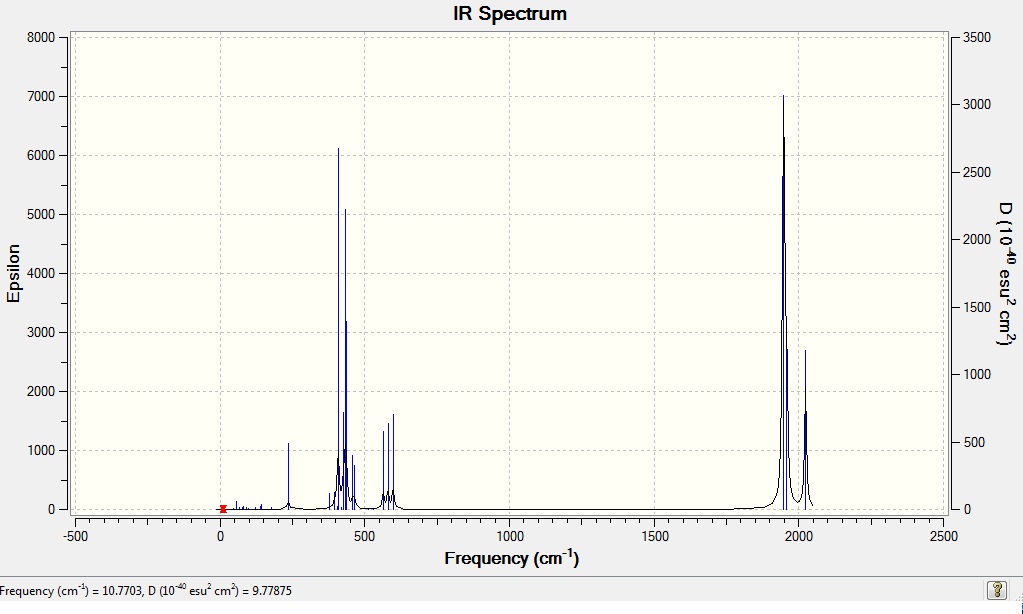

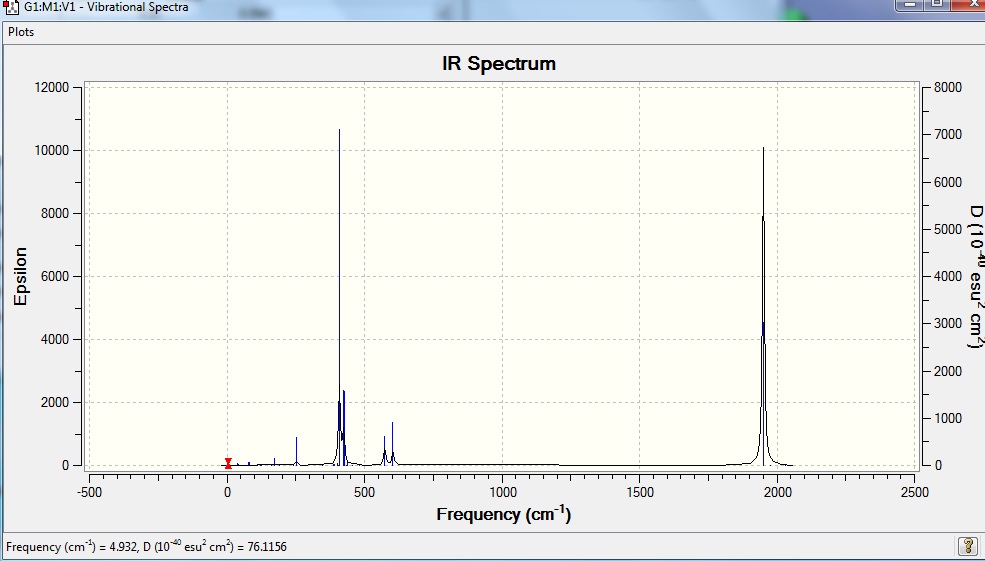

Vibrational analysis of Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 isomers

To prove that the minima had indeed been found, frequency analysis was carried out on the isomers.

45 modes of vibrations were found for both isomers. Since the frequencies were all positive, we can confirm that the minima were reached.

Vibrations with very low frequencies are shown in the table below.

The low frequency vibrations are associated with low intensities. From the equation E=h x f, where E is the energy, h is the Planck constant, and f is the frequency, it can be deduced that the lower the vibrational frequency the lower the energy is associated and therefore at room temperature, the molecule would already possess enough energy to overcome the low frequency modes and vibrate.

The carbonyl stretching frequencies computed for cis and trans isomers are shown in the table below:

| Isomer | Computed Frequency from vibrational modes cm-1 | Computed Intensity | Literature frequency[7] cm-1 | Symmetry (Point Group C2v Symmetry)[7] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cis | 1945 | 763 | 1986 | B2 |

| 1949 | 1498 | 1994 | B1 | |

| 1958 | 632 | 2004 | A1 | |

| 2023 | 598 | 2072 | A1 | |

| trans | 1950 | 1475 | 1896 | Eu |

| 1951 | 1467 | 1896 | Eu | |

| 1977 | 1 | - | B1g | |

| 2031 | 4 | - | A1g |

The computed data resemble the trend as literature values. However, the carbonyl stretch frequencies computed for cis isomer are in general less than the literature values; whereas the computed values for trans isomer are greater than the literature values.

Only one vibrational frequency was found for trans isomer from literature. In the literature it is suggested that a metal carbonyl complex has a cis geometry if four peaks are found in the CO stretch region of IR; whereas if one peak is found in that region it has a trans geometry.[8]

To determine how many vibrational modes arise from the isomer, group theory can be applied.

For cis isomer, Гirreducible = 2A1 + B1 + B1

For trans isomer, Гirreducible = A1g + B1g + Eu

All the four modes are infrared active for cis, whereas only the Eu mode is active for trans. Therefore four bands are expected for the cis isomer whereas one active band is expected for the trans isomer. There is a general rule for infrared activity: the more symmetric the molecule, the fewer infrared active bands are to be expected.[9]

From the computed IR spectra, it can be seen that only one peak is shown in the CO stretching region for the trans isomer even though four modes of vibrations were found. This is due to the low intensities of the vibrational modes 44 and 45, 1 and 4 respectively, which are too low to be observed. The remaining two modes 42 and 43 are degenerate set of vibration, with vibrational frequency of 1950 and 1951cm-1 respectively, and therefore they appear to be one high intensity peak in the IR spectrum. This also explains why only one vibrational frequency was found for trans isomer from the literature, instead of the four found from computed vibrational modes.

Mini project

Binding of CO and CN- to 4d transition metal trimers

For the mini project, Gaussview05 was used and the computation method B3LYP and basis set GEN were mainly used to determine the energies and minima of Nb3CO and Mo3CO. Nb3CN- was also computed since CN- is isoelectronic with CO. The effect of changing substituent bound to the transition metal trimer was investigated.

Originally I was going to investigate the associative versus dissociative binding of CO to 4d transition metal trimers by examining the stabilities of the associative and dissociative structures. Nb3 and Ru3 trimers systems were decided to be examined since CO binds onto Nb3 trimer dissociatively, whereas it binds onto Ru3 trimer associatively[10]. However, due to the computational problems encountered with Ru3CO, which could not be resolved in the limited period of time, Molybdenum, which is also a 4d transition metal, was decided to be investigated instead.

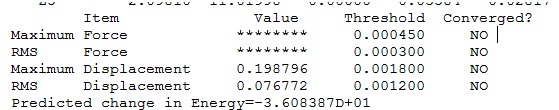

For Ru3CO, error messages were encountered in the output log file after the optimisation job was run by HPC system. The log file was opened in wordpad and from the “Item” section, it was shown that the optimisation did not converge. Therefore, "int=ultrafine scf=conver=9" was added in the additional key words part in order to increase the electronic convergence. The job came back with the error message in the output file again. To try solve this problem, the Ru-Ru bonds in the Ru3CO molecule were fixed manually to the suggested literature value of 2.755 Angstroms, in the hope that the molecule would be optimised. However, that did not work either.

A lot of time was spent on understanding what went wrong in the input and output files and due to the time constraint, I decided to investigate the Mo3CO molecule instead which is similar to Ru3CO, but CO binds onto the Mo3 trimer dissociatively like Nb3 trimer instead of associatively like Ru3.

For the optimised Nb3CO, the frequency analysis job was run but it turned out that there was error associated with the file. The output log file was checked and from the “Item” section it can be seen that there were no convergences.

The non-optimised file was probably opened instead of the optimised one when the calculation settings were input for the frequency analysis. As a result, the log file from the optimised structure was downloaded from the HPC server instead of the checkpoint file and it was renamed and re-saved to ensure the optimised structure is used for the frequency analysis. This solved the problem and led to all positive vibrational frequencies indicating the global minimum point was found.

Optimisaton of Nb3CO

Nb3CO trimer was optimised using the method B3LYP and basis set GEN in Gaussview05. Additional keywords "pseudo=cards gfinput" were added and the input 'gjf' file was editted with the addition of pseudo potential before submitted onto HPC. Since the trimer contains a heavy atom Nb with a high electron count, it has to be modelled by pseudo potential which assumes that the core electrons in the atom does not contribute much to the bonding interactions.

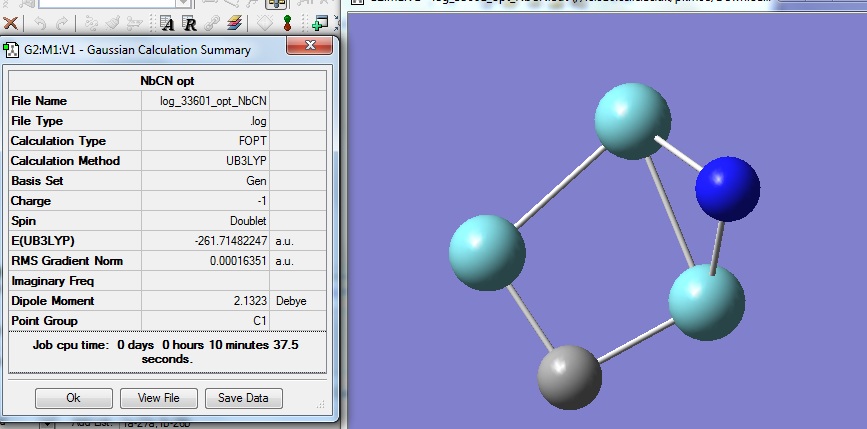

The summary table and structure of the optimised Nb3CO is shown below.

The energy for this optimised structure is -282.18a.u., which is consistent with literature value of -285.13a.u..

The optimised bond lengths for Nb-Nb are 2.44, 2.49 and 2.80A, which correspond well with the literature values obtained which are 2.29, 2.39 and 2.46A[11]

The structure has a dipole moment of 3.14 debye and its point group is C1. The RMS gradient is very close to zero indicating successful optimisation.

Optimisation for Nb3CO: DOI:10042/to-5996

Frequency analysis of Nb3CO

To confirm that the minimum point had been found, a frequency analysis was carried out on the optimised structure. The input ‘gjf’ file was edited in a similar way as above, but the ‘opt’ function was replaced with ‘freq’.

The positive frequencies obtained from the results prove that the global minimum point had indeed been found.

Frequency analysis for Nb3CO: DOI:10042/to-5993

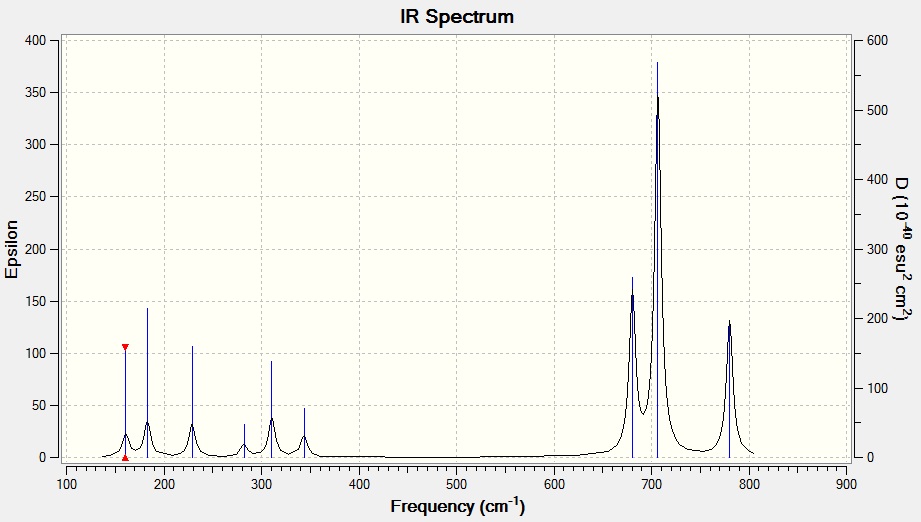

(3N-6) rule for non- linear molecule predicts the number of vibration modes to be (3x5-6) which is 9 modes. The computed real vibrational modes confirm this and are shown in the table below.

| No. | Mode of vibration | Frequency cm-1 | Intensity |

| 1 |  |

161 | 6 |

| 2 |  |

183 | 10 |

| 3 |  |

229 | 9 |

| 4 |  |

282 | 4 |

| 5 |  |

311 | 11 |

| 6 |  |

344 | 6 |

| 7 |  |

681 | 44 |

| 8 |  |

707 | 101 |

| 9 |  |

780 | 38 |

The computed IR spectrum matches well with the prediction from (3N-6) modes of vibrations rule and 9 peaks were observed. The intensities of the peaks relate to the heights of the peaks. Since the intensities of all the 9 modes are greater than zero, all the modes are infrared active.

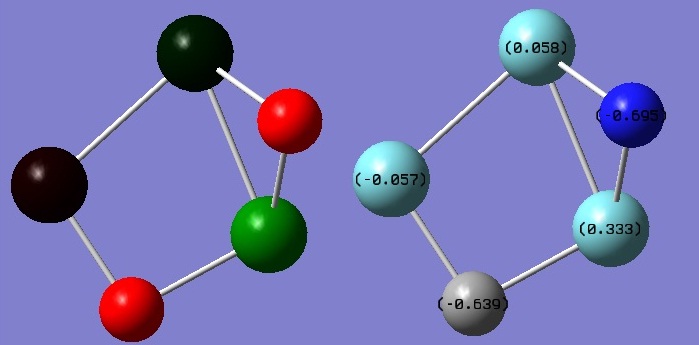

NBO analysis of Nb3CO

The summary table above shows that the structure has a dipole moment of 3.14 debye. This is confirmed by the numerical values shown above from the NBO analysis. Positive values and bright green regions correspond to positive area whereas negative values and dark red regions represent negative regions.

Molecular Orbitals for HOMO and LUMO

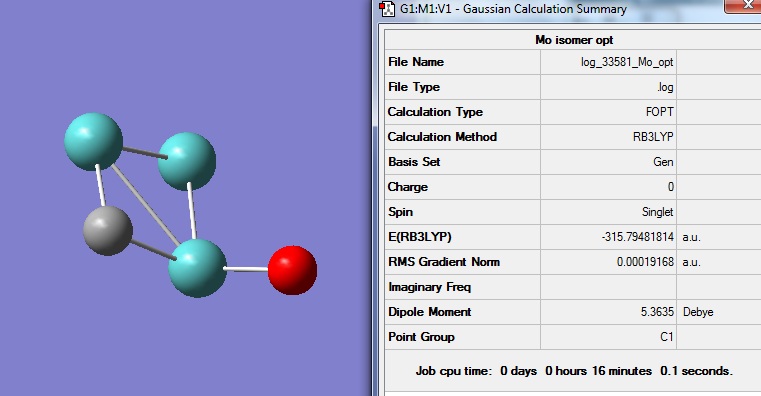

Optimisation of Mo3CO

The same method and basis set for the analysis carried out for Nb3CO above were used to analyse Mo3CO in order to allow comparison to be made later.

The structure and summary table from the optimisation are shown below.

The energy for this optimised structure is -315.79a.u., which is consistent with literature value of -318.89a.u..

The optimised bond lengths for Mo-Mo are 2.21, 2.33 and 2.71A. No literature values were recorded.

The structure has a dipole moment of 5.36 debye and its point group is C1. The molecule is not highly symmetric and therefore the dipole moments cannot be cancelled out leading to considerable dipole moment. The RMS gradient is very close to zero indicating another successful optimisation.

Optimisation for Mo3CO: DOI:10042/to-5997

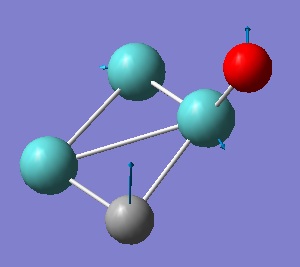

Vibration analysis of Mo3CO

Again, as above, frequency analysis was carried out on the optimised structure to prove that the global minimum point had been found. The positive frequencies obtained means successful optimisation.

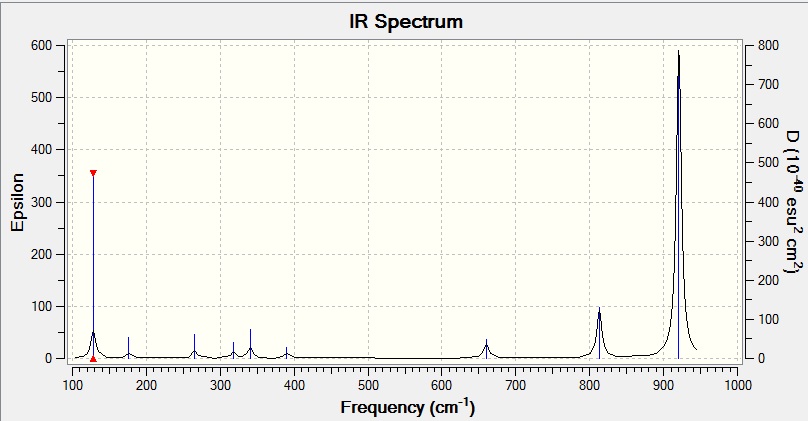

Again, 9 modes of vibrations are predicted from (3N-6) rule for non- linear molecule, i.e.(3x5-6). The computed real vibrational modes confirm this and are shown in the table below.

Frequency analysis for Mo3CO: DOI:10042/to-5994

| No. | Mode of vibration | Frequency cm-1 | Intensity |

| 1 |  |

128 | 15 |

| 2 |  |

176 | 2 |

| 3 |  |

265 | 4 |

| 4 |  |

318 | 3 |

| 5 |  |

340 | 6 |

| 6 |  |

390 | 3 |

| 7 |  |

660 | 8 |

| 8 |  |

813 | 26 |

| 9 |  |

921 | 173 |

The computed IR spectrum matches well with the prediction from (3N-6) modes of vibrations rule and 9 peaks were observed. The intensities of the peaks relate to the heights of the peaks. Since the intensities of all the 9 modes are greater than zero, all the modes are infrared active.

NBO analysis of Mo3CO

The summary table above shows that the structure has a dipole moment of 5.36 debye. This is again confirmed by the numerical values shown above from the NBO analysis.

Optimisation of Nb3CN-

The CO substituent attached to Nb3 trimer was replaced by isoelectronic CN-.

The optimised structure has an energy of -261.71a.u., which is the highest amongst the three molecules which are compared in this project. The optimised bond lengths for Nb-Nb are 2.47 and 2.48A. The dipole moment of the structure is 2.13 debye. No literature values were recorded for comparison. The RMS gradient is again very close to zero meaning successful optimisation.

Optimisation for Nb3CN-: DOI:10042/to-5998

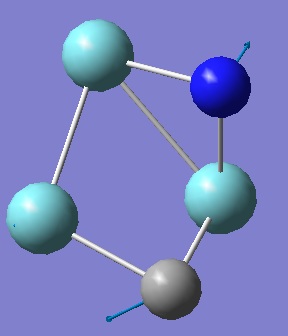

Vibrational analysis of Nb3CN-

Frequency analysis was carried out on the optimised structure. The input ‘gjf’ file was edited in a similar way as above with the inclusion of pseudo potential.

The positive frequencies obtained from the results confirm that the global minimum point had been found.

Frequency analysis for Nb3CN-: DOI:10042/to-5995

Similarly, the(3N-6) rule for non- linear molecule predicts the number of vibration modes to be 9. The computed real vibrational modes confirm this and are shown in the table below.

| No. | Mode of vibration | Frequency cm-1 | Intensity |

| 1 |  |

152 | 17 |

| 2 |  |

180 | 16 |

| 3 |  |

258 | 7 |

| 4 |  |

284 | 9 |

| 5 |  |

299 | 2 |

| 6 |  |

414 | 12 |

| 7 |  |

630 | 22 |

| 8 |  |

751 | 89 |

| 9 |  |

777 | 62 |

The computed IR spectrum matches well with the prediction from (3N-6) modes of vibrations rule and 9 peaks were observed. The intensities of all the 9 modes are greater than zero, all the modes are infrared active. No degenerate sets of vibrations were found.

NBO analysis of Nb3CN-

The NBO analysis shows a match with debye results shown in the summary table. The structure is again not highly symmetric and therefore dipole moment is observed.

Comparison between Nb3CO, Mo3CO and Nb3CN-

The molecular weight of the molecules are very similar since they are in the same period. The longer the bond length, the higher the vibrational frequency, and the more energy is associated with the vibration.

Both molecules have dipole moments due to asymmetries in structures where the charges cannot be cancelled out. Mo3CO is less symmetric than Nb3CO and therefore results in slightly higher dipole moment of about 2 debye. The NBO analysis shows how the charges are spread across the molecules numerically and graphically.

The negative charge present in the Nb3CN- molecule could have destabilised the structure compared to its analogue Nb3CO where CO is iosoelectronic as CN-. Nb3CN- is about 20a.u. less stable compared to Nb3CO. The relative energies can be compared since the calculations were carried out using the same method and basis set.

All the geometries for the three molecules generated are slightly different, even though they are similar in electron count and they are all 4d transition metal trimers. All the frequency analysis carried out showed that these structures are indeed at their global minimum points and therefore are stable. The missing diagonal C-Nb bond in Nb3CN- could be caused by the limited bond distance range set in Gaussview which when the two atoms are outside the set range the bond would not be shown.

For Mo3CO, the molecule is more stable when the ring is opened with the Mo-O bond broken. The molecule experiences less strain and is therefore is a stable configuration with the overall energy about 30a.u. lower than Nb3CO. However, this does not apply to Nb3CO where the ring-opened form appears from literature to be less stable than the structure shown in this investigation[12].

Conclusion

This lab illustrated how powerful computational chemistry is in visualising the molecules and predicting the relative stabilities and their IR spectra. Computed data like bond lengths and angles match well with literature values and therefore they are reliable to be used.

Reference

- ↑ F. Allen, I. Bruno, Acta Crystallographica Section B, 2010, 66(3), 380–386 DOI:10.1107/S0108768110012048

- ↑ William H. Brown, Christopher S. Foote, “Organic Chemistry”, 1995, 2nd Edition, pg 227

- ↑ Schuurman, M. S., Allen, W. D. and Schaefer, H. F., Journal of Computational Chemistry, 2005, 26, 1106–1112, DOI:10.1002/jcc.20238/

- ↑ M. Atanasov and D. Reinen, J. Phys. Chem. A, 2001, 105 (22), pp 5450–5467 DOI:10.1021/jp004511j

- ↑ D. W. Bennett, T. A. Siddiquee, D. T. Haworth, S. E. Kabir, F. K. Camellia, J. Chem. Crys., 2004, 34, 353-359.DOI:10.1023/B:JOCC.0000028667.12964.28

- ↑ D. J. Darensbourg, R. L. Kump, Inorg. Chem., 1978, 17, 2680-2682. DOI:10.1021/ic50187a062

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 F.A. Cotton, Inorg. Chem., 1964, 3, 702: DOI:10.1021/ic50015a024

- ↑ D. J. Darensbourg, R. L. Kump, Inorg. Chem., 1978, 17, 2680-2682 DOI:10.1021/ic50187a062

- ↑ D. J. Darensbourg, R. L. Kump, Inorg. Chem., 1978, 17, 2680-2682 DOI:10.1021/ic50187a062

- ↑ M. A. ADDICOAT, M. A. BUNTINE, B. YATES, G. F. METHA, Journal of Computational Chemistry, 2008, 29, 1497–1506, DOI:10.1002/jcc.20912 10.1002/jcc.20912

- ↑ M. A. ADDICOAT, M. A. BUNTINE, B. YATES, G. F. METHA, Journal of Computational Chemistry, 2008, 29, 1497–1506, DOI:10.1002/jcc.20912 10.1002/jcc.20912

- ↑ M. A. ADDICOAT, M. A. BUNTINE, B. YATES, G. F. METHA, Journal of Computational Chemistry, 2008, 29, 1497–1506, DOI:10.1002/jcc.20912 10.1002/jcc.20912