Rep:Mod:physical module3

Cope Rearrangement

Introduction

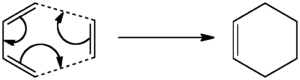

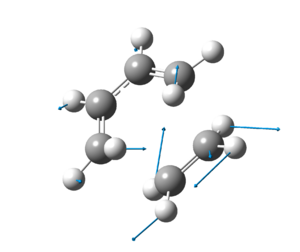

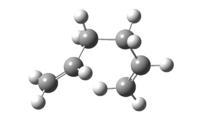

The Cope rearrangement is a [3,3]-sigmatropic shift rearrangement. An example is shown in figure 1 below, illustrating the Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene. It involves the concerted migration of an allyl group from one point of attachment to a conjugated system to another point of attachment, during which one σ bond is broken and another σ bond is made.

Figure 1: Cope Rearrangement - [3,3]-sigmatropic shift rearrangement

It has been generally accepted that the Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene occurs via either a “chair” or “boat” transition state, where the former is energetically more favourable than the latter.

The aim of this exercise is to study the Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene to learn how to investigate a chemical reactivity problem using Gaussian. Several conformers of the reactants would first be optimised to determine the most stable conformer. To determine the preferred reaction mechanism, calculations would be performed to locate the low-energy minima and transition structures on the 1,5-hexadiene potential energy surface. IRC calculations would also be performed to connect the transition state to a particular conformer.

Optimisation of Reactants and Products

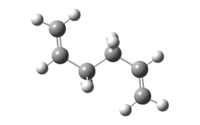

Conformers of 1,5-hexadiene

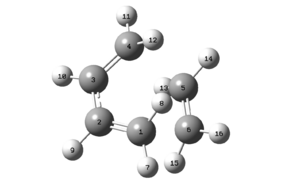

Several conformers of 1,5-hexadiene were drawn in gaussview, where the central 4 carbon atoms have either “anti” or “gauche” linkages. All conformers were then optimized at the HF/3-21G level of theory. The energies and point groups of the optimized structures are shown in table 1 below. The relative energy of the conformers were calculated with respect to the most stable conformer, which in this case is gauche conformer 3.

Table 1: Conformers of 1,5-hexadiene

| Conformer | Structure | Jmol | Point Group | Energy/ Hartrees (HF/3-21G) | Relative Energy/ kcal mol-1 | Log File |

| Anti1 |  |

C2 | -231.69260 | 0.04 | https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/d/d7/Wsc108_anti_1.log | |

| Anti2 |  |

Ci | -231.69254 | 0.08 | https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/c/c1/Wsc108_anti_2.log | |

| Anti3 |  |

C2h | -231.68907 | 2.25 | https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/f/f9/Wsc108_anti_3.log | |

| Anti4 |  |

C1 | -231.69097 | 1.06 | https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/d/d3/Wsc108_anti_4.log | |

| Gauche1 |  |

C2 | -231.68772 | 3.10 | https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/e/eb/Wsc108_gauche_1.log | |

| Gauche2 |  |

C2 | -231.69167 | 0.62 | https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/5/54/Wsc108_gauche_2.log | |

| Gauche3 |  |

C1 | -231.69266 | 0.00 | https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/2/2a/Wsc108_gauche_3.log | |

| Gauche4 |  |

C2 | -231.69153 | 0.71 | https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/b/b7/Wsc108_gauche_4.log | |

| Gauche5 |  |

C1 | -231.68962 | 1.91 | https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/d/d5/Wsc108_gauche_5.log | |

| Gauche6 |  |

C1 | -231.68916 | 2.20 | https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/c/cb/Wsc108_gauche_6.log |

It was expected that conformers with the “gauche” linkage would experience greater steric repulsions, hence conformers with the “anti” linkage were expected to be more stable. However, based on the results shown in table 1 above, the most stable conformer was the gauche conformer 3. This is due to the CH-π interaction present in the gauche conformer, where the stereoelectronic interaction between the C=C π electrons and the adjacent vinyl proton stabilizes the gauche conformer.[1]

Optimisation of Anti2 Conformer of 1,5-Hexadiene

The anti2 conformer was reoptimized at B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory. The results are shown in table 2 below, together with the results obtained at the HF/3-21G level of theory.

Table 2: Comparison of Anti2 Conformer Calculated using Different Methods and Basis Sets

| HF/ 3-21G | DFT/ B3LYP/ 6-31G* | |

| Log File | https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/c/c1/Wsc108_anti_2.log | https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/6/6a/Wsc108_anti_2_dft.log |

| Jmol | ||

| Image |  |

|

| Point Group | Ci | Ci |

| Energy/ Hartrees | -231.69254 | -234.61170 |

| C1=C2 Bond Length/ Å | 1.32 | 1.33 |

| C2-C3 Bond Length/ Å | 1.51 | 1.50 |

| C3-C4 Bond Length/ Å | 1.55 | 1.55 |

| C4-C5 Bond Length/ Å | 1.51 | 1.50 |

| C5=C6 Bond Length/ Å | 1.32 | 1.33 |

| C1-C2-C3-C4 Dihedral Angle/o | 114.6 | 118.5 |

| C2-C3-C4-C5 Dihedral Angle/o | 180.0 | 180.0 |

| C3-C4-C5-C6 Dihedral Angle/o | -114.6 | -118.5 |

The geometry of the anti2 conformer calculated at the 2 different levels of theories were rather similar. The C-C bond lengths differed from each other only by 0.01Å. The dihedral angle between the 4 terminal carbons was 4o larger when the anti2 conformer was optimised using the DFT/B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory.

Thermochemistry of Anti2 Conformer of 1,5-Hexadiene

Frequency calculations can serve several different purposes. Besides identifying the nature of stationary points on the potential energy surface, frequency calculations also allow us to compute zero-point vibration and thermal energy corrections to total energies as well as the enthalpy and entropy of the system. [2]

Frequency calculations were carried out on the optimised anti2 conformer at 0K and 298.15K at both the HF/3-21G and DFT/B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory. No imaginary frequency was observed and the results of the energies are shown in table 3 below.

Table 3: Comparison of Thermochemistry of Anti2 Conformer at Different Temperatures

| HF/ 3-21G | DFT/ B3LYP/ 6-31G* | |||

| 298.15K, 1atm | 0K, 1atm | 298.15K, 1atm | 0K, 1atm | |

| Sum of Electronic and Zero-Point Energies/ Hartrees | -231.53954 | -231.53907 | -234.46921 | -234.46878 |

| Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies/ Hartrees | -231.53257 | -231.53211 | -234.46186 | -234.46143 |

| Sum of Electronic and Thermal Enthalpies/ Hartrees | -231.53162 | -231.53116 | -234.46091 | -234.46049 |

| Sum of Electronic and Thermal Free Energies/ Hartrees | -231.57091 | -231.57043 | -234.50082 | -234.50037 |

| Link to Frequency Calculations | DOI:10042/to-7161 | DOI:10042/to-7159 | DOI:10042/to-7162 | DOI:10042/to-7160 |

It is observed that the anti2 conformer possesses higher energy at 0K than at 298.15K. This is expected as at higher temperature, the molecules would absorb more heat energy, hence the thermal component of the total energy increases.

Optimisation of "Chair" and "Boat" Transition States

Optimisation of "Chair" Transition State

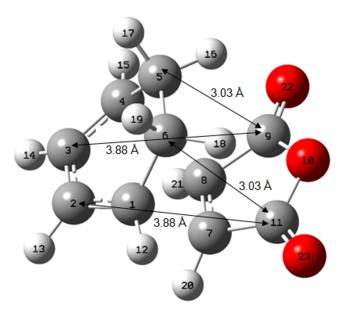

Two different methods were used to optimize the “chair” transition state at the HF/3-21G level of theory. The first method involves using TS(Berny) directly by computing the force constants once at the beginning of the optimization. The second method involves 2 steps that make use of the redundant coordinate editor: the 2 bonds that break or form were first fixed at 2.2 Å and the resultant structure was optimized to a minimum; the bond forming or breaking distances were subsequently optimized in the next step where the condition to fix the bonds was released and the structure was optimized using TS(Berny) without computing the force constants. The results from both methods are shown in table 4 below.

Table 4: Comparison of Optimised "Chair" Transition States Using Different Approaches

| TS (Berny) Method | Frozen Coordinate Method | |

| Jmol | ||

| Image |  |

|

| Point Group | C2h | C2h |

| Energy/ Hartrees | -231.61932 | -231.61932 |

| Bond-Forming Length/ Å | 2.02 | 2.02 |

| Bond-Breaking Length/ Å | 2.02 | 2.02 |

| Imaginary Frequency/ cm-1 | -818 | -818 |

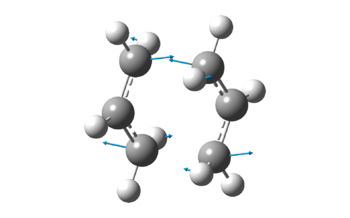

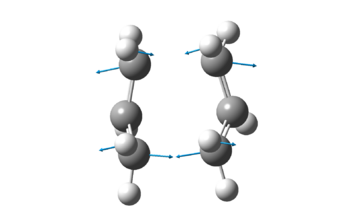

| Vibration at Imaginary Frequency |  |

|

| Log File | https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/2/28/Wsc108_chair_ts_berny.log | https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/c/c2/Wsc108_chair_ts_redundant_coordinate.log |

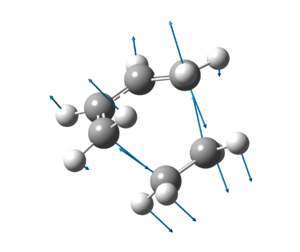

Both methods gave exactly the same results, after factoring in the accuracy of Gaussian calculations. It is important to note that there is an imaginary frequency at -818cm-1, which corresponds to the concerted bond formation and bond breaking reaction involved in the [3,3]-sigmatropic pericyclic Cope rearrangement reaction. The fact that there is an imaginary frequency also confirms the fact that the structures obtained are transition states.

Optimisation of "Boat" Transition State

The “boat” transition state was optimized using the QST2 method at the HF/3-21G level of theory, where both the reactant and product were specified and the calculation interpolates between the two structures to obtain the transition state between them. One of the disadvantages of the QST2 method is that the reactants and products specified need to be very close to the transition structure for the optimization to work. Hence, when the geometry of the reactant and product was not close enough to the “boat” transition state, the calculation failed. The results obtained after modifying the geometry of the reactant and product to resemble the “boat” transition state are shown in table 5 below.

Table 5: Optimised "Boat" Transition State

| QST2 | |

| Jmol | |

| Image |

|

| Point Group | C2v |

| Energy/ Hartrees | -231.60280 |

| Bond-Forming Length/ Å | 2.14 |

| Bond-Breaking Length/ Å | 2.14 |

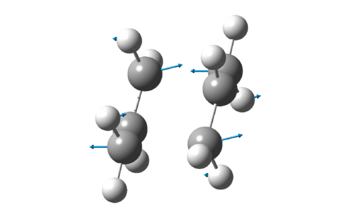

| Imaginary Frequency/ cm-1 | -840 |

| Vibration at Imaginary Frequency |

|

| Log File | https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/4/4d/Wsc108_boat_ts_qst2.log |

As is the case for the "chair" transition state, the imaginary frequency at -840cm-1 corresponds to the concerted bond formation and bond breaking reaction involved in the [3,3]-sigmatropic pericyclic Cope rearrangement reaction. The presence of an imaginary frequency suggests that the structure obtained is indeed a transition state.

It is also observed from both tables 4 and 5 above that the energy of the "boat" transition state is higher than that of the "chair" transition state. This is because the “chair” transition state experiences the least possible steric repulsion with a staggered conformation whereas the “boat” transition state has a eclipsed conformation, hence the great torsional strain between the eclipsed carbons and hydrogens results in a structure with higher energy. This suggests that the Cope rearrangement would involve a lower activation energy if the reaction proceeds via the “chair” transition state. This would be verified in section 1.3.4.

Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) of "Chair" Transition State

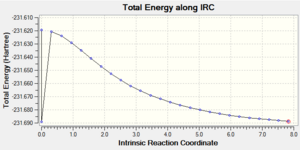

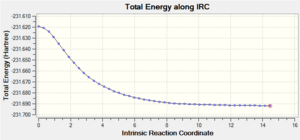

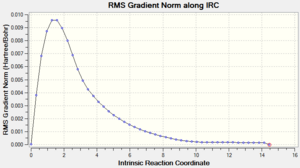

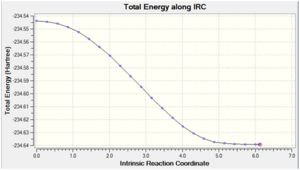

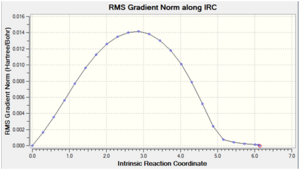

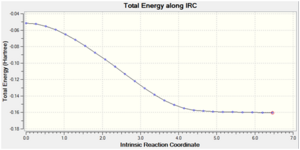

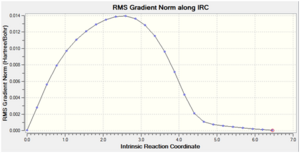

As it was impossible to predict which conformer the reaction path from the transition structure will lead to, the Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) was calculated for the “chair” transition state. 4 different methods were used, where the reaction coordinate was computed only in the forward direction as the reaction coordinate in this case is symmetrical.

Table 6: Obtaining IRC of "Chair" Transition State using Different Methods

| Method | Minimum Geometry Obtained | Energy/ Hartree | Total Energy Along IRC | Gradient Along IRC | Structure | Link to IRC calculations |

| 1: IRC Involving 50 Points, Calculating Force Constant Once | No | -231.68863 |  |

|

|

DOI:10042/to-7163 |

| 2: Normal Minimisation Based On Last Point On IRC | Yes | -231.69167 | - | - |  |

DOI:10042/to-7164 |

| 3: IRC involving 200 Points, Calculating Force Constant Once | No | -231.68863 |  |

|

|

DOI:10042/to-7165 |

| 4: IRC Involving 50 Points, Calculating Force Constant Always | Yes | -231.69166 |  |

|

|

DOI:10042/to-7166 |

Ideally, the energy of the last few points in the IRC paths should form a plateau where the final point corresponds to the minimum structure with a RMS gradient as close to zero as possible. The first method did not result in a structure with a minimum geometry. This can be seen as the decreasing energy has yet to reach a plateau and the RMS gradient is still quite far from zero. When a normal minimization was performed on the last point of the IRC, a structure with a minimum geometry was obtained. The danger of this second method is that if the last point of the IRC does not resemble the local minimum well enough, a wrong minimum structure would be obtained. The third method did not result in a structure with a minimum geometry as well; in fact, both the jobs from the first and third methods stopped after computing 27 points on the IRC. The disadvantage of the third method is that if too many points are needed, a wrong minimum structure might be observed after some time as well. The final method resulted in a minimum structure, which can be seen as the decreasing energy reaches a plateau and the RMS gradient is almost zero. This structure has almost the same energy and geometry as that obtained from the second method. Hence, in this case, the last point of the IRC from the first method resembles the local minimum enough to give the correct minimum structure using the second method. It should also be noted that while the final method seems to be the most reliable, it is the most expensive and might not be feasible for large systems; in this case, the job took 12 minutes 54.0 seconds.

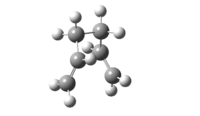

The minimum structure obtained from methods 2 and 4 corresponds to the gauche2 conformer, which has an energy of -231.69167 Hartrees.

Activation Energies for "Chair" and "Boat" Transition States

To calculate the activation energies for the Cope rearrangement via both the “chair” and “boat” transition structures, both the transition structures were reoptimised at DFT/B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory, starting from the optimized structure obtained at the HF/3-21G level. The geometries of the transition states obtained at the two different levels of theory were very similar. Frequency calculations were carried out at 0K and 298.15K. A summary of the results obtained at the two temperatures at the two different levels of theory is shown in table 7 below.

Table 7: Energies of "Chair" and "Boat" Transition States at 0K and 298.15K at HF/3-21G and B3LYP/6-31G* Level of Theories

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | |||||

| Electronic Energy/ Hartress | Sum of Electronic and Zero-Point Energies/ Hartrees | Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies/ Hartrees | Electronic Energy/ Hartress | Sum of Electronic and Zero-Point Energies/ Hartrees | Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies/ Hartrees | |

| at 0K | at 298.15K | at 0K | at 298.15K | |||

| Chair TS | -231.61932 | -231.46622 DOI:10042/to-7170 | -231.46134 | -234.55698 | -234.41449 DOI:10042/to-7168 | -234.40901 |

| Boat TS | -231.60280 | -231.45046 DOI:10042/to-7169 | -231.44530 | -234.54309 | -234.40190 DOI:10042/to-7167 | -234.39601 |

| Reactant (Anti2) | -231.69254 | -231.53907 | -231.53257 | -234.61171 | -234.46878 | -234.46186 |

The activation energies, ΔE, can then be calculated for each reactant pathway via the “chair” or “boat” transition states by taking the difference between the energy of the reactant anti2 and the energy of the respective transition states. It is important to note that the energy of reactant anti2 at 0K is the sum of electronic and zero-point energies whereas at 298.15K, it is the sum of electronic and thermal energies that represent the energy of reactant anti2. A summary of the activation energies for the two transition states at the two temperatures is shown in table 8 below.

Table 8: Activation Energies

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | Experimental Value | |||

| at 0K | at 298.15K | at 0K | at 298.15K | at 0K | |

| ΔE (Chair TS)/ kcal mol-1 | 45.71 | 44.69 | 34.07 | 33.16 | 33.5 ± 0.5 [3] |

| ΔE (Boat TS)/ kcal mol-1 | 55.60 | 54.76 | 41.96 | 41.32 | 44.7 ± 2.0 [3] |

As can be seen from the results, the activation energy for the “chair” transition state is always lower than that for the “boat” transition state. This is consistent with the results presented earlier, where the “boat” transition state has a higher energy than the “chair” transition state due to a greater steric repulsion in the former structure as discussed earlier.

In addition, it is observed that there is a good correlation between the calculations performed at the DFT/B3LYP/6-31G level of theory and experimental results, although the experimental activation energy for the “boat” transition state is slightly higher than that calculated.

Diels Alder Cycloaddition

Introduction

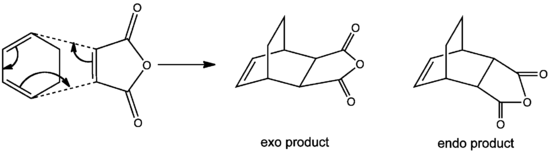

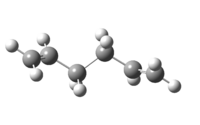

A Diels Alder cycloaddition is a pericyclic reaction involving 2 π systems – a diene contributing 4π electrons and a dienophile contributing other 2π electrons. 2 new σ bonds are formed between the termini of the diene and dienophile in the concerted reaction. Two examples of a Diels Alder cycloaddition would be studied here – the prototypical reaction between cis-butadiene and ethylene as well as the reaction between cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride as shown in Figures 2 and 3 respectively.

Figure 2: Prototypical Reaction between Cis-Butadiene and Ethylene

Figure 3: Reaction between Cyclohexa-1,3-diene and Maleic Anhydride

Reaction Between Cis-Butadiene and Ethylene

Molecular Orbitals of Reactants

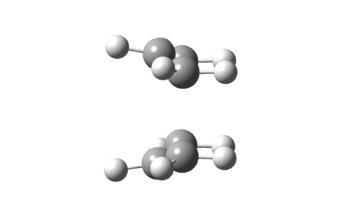

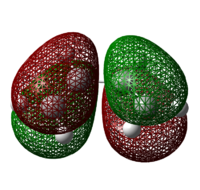

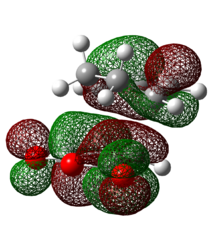

Both the reactants – cis-butadiene and ethylene are optimized at the Semi-Empirical/AM1 level of theory. The HOMOs and LUMOs are shown in table 9 below. The molecular orbital is said to be “symmetric” if there is a plane of symmetry in the centre of the molecule and "anti-symmetric" if the plane of symmetry in the centre of the molecule is absent.

Table 9: Molecular Orbitals of Cis-Butadiene and Ethylene

| Butadiene | Ethylene | |||

| HOMO | LUMO | HOMO | LUMO | |

| Molecular Orbital |  |

|

|

|

| Energy/ Hartrees | -0.34453 | 0.01793 | -0.38775 | 0.05284 |

| Symmetry | Anti-symmetric | Symmetric | Symmetric | Anti-symmetric |

For a reaction to be considered "allowed", the HOMO of one reactant must interact with the LUMO of the other reactant, which can only occur when the orbitals have the same symmetry properties, hence allowing significant overlap density. As the HOMO of ethylene and the LUMO of butadiene are both symmetric while the LUMO of ethylene and the HOMO of butadiene are both anti-symmetric, it can be inferred that it is the HOMO-LUMO pairs of orbital that interact, resulting in an "allowed" Diels Alder cycloaddition, where 2 new σ bonds are formed.

Optimisation of Transition State

The transition state of the Diels Alder cycloaddtion between cis-butadiene and ethylene was optimized using two methods employed in the optimization of the “chair” transition state previously – the direct TS (Berny) method and the frozen coordinate method. An initial guess structure was drawn by inserting the bicyclo[2,2,1]heptane into Guassview, removing the bridged CH2 group and adding in the relevant double bonds. TS (Berny) was employed directly in the first method and force constants was calculated once at the beginning of the optimization. In the second method, the redundant coordinate editor was used to fix the bond breaking or forming bonds to 2.2 Å, optimizing the structure to a minimum, followed by releasing that condition and optimizing it to a transition state using TS (Berny).

Table 10: Optimisation of Transition States

| TS (Berny) Method | Frozen Coordinate Method | |

| Jmol | ||

| Image |  |

|

| Point Group | Cs | Cs |

| Energy/ Hartrees | 0.11165 | 0.11165 |

| Imaginary Frequency/ cm-1 | -956 | -957 |

| Bond-Forming Length/ Å | 2.12 | 2.12 |

| Bond-Breaking Length/ Å | 2.12 | 2.12 |

| Link to Transition State Optimisation | DOI:10042/to-7183 | DOI:10042/to-7184 |

As can be seen from the energy of the molecule and bond-breaking/forming lengths, both methods gave exactly the same results after factoring in the accuracy of Gaussian calculations. The presence of an imaginary frequency confirms that the structure obtained is indeed a transition state.

Geometry of Transition State

The geometry of the transition state obtained from the two methods and some typical values of bond lengths are shown in tables 11 and 12 respectively.

Table 11: Geometry of Transition State from Two Diffferent Methods

Table 12: Literature Values

| Literature Values | |

| Typical sp3 C-C Bond Length/ Å | 1.53 [4] |

| Typical sp2 C-C Bond Length/ Å | 1.48 [4] |

| Van der Waals Radius of Carbon/ Å | 1.70 [5] |

As the C-C bond lengths of C4-C5 and C6-C1 are 2.12 Å, which is longer than a typical sp3 C-C bond but shorter than two Van der Waals radius of carbon, it can be deduced that the C-C bonds are in the process of formation but a complete C-C bond has yet to be formed.

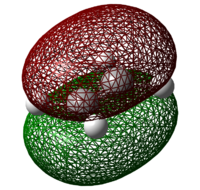

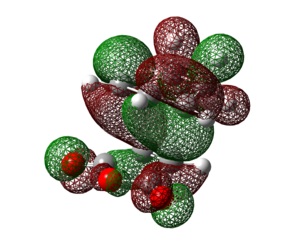

Molecular Orbitals of Transition State

The HOMO and LUMO of the transition state is shown in table 13 below. Again, the molecular orbital is said to be “symmetric” if there is a plane of symmetry in the centre of the molecule and "anti-symmetric" if such a plane of symmetry does not exist.

Table 13: Molecular Orbitals of Transition State

| HOMO | LUMO | |

| Molecular Orbital |  |

|

| Energy/ Hartrees | -0.32395 | 0.02318 |

| Symmetry | Anti-symmetric | Symmetric |

The HOMO of the transition state is anti-symmetric. It is made up of the anti-symmetric HOMO of cis-butadiene and the anti-symmetric LUMO of ethylene, where the HOMO of the diene interacts with the LUMO of the dienophile. Based on the pericyclic reaction selection rules, under thermal conditions, a pericyclic reaction involving 4n+2 electrons would result in a product with suprafacial stereochemistry via a Huckel aromatic transition state. In this case, the Diels Alder reaction involves 6 π electrons and the bond forms over the same face of the butadiene and ethylene, demonstrating suprafacial attack. As this reaction follows the pericyclic reaction selection rules, the reaction is allowed.

Vibrations of Transition State

The vibration with a negative frequency and the lowest positive frequency are shown in table 14 below.

Table 14: Vibrations of Transition State

The vibration with the negative frequency of -957 cm-1 illustrates the synchronous formation of the two σ bonds during the Diels Alder reaction. This differs from the vibration with the lowest positive frequency of 147 cm-1 which mainly involves vibrations of the hydrogen atoms.

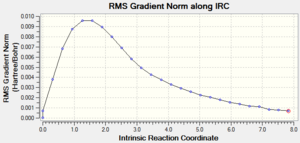

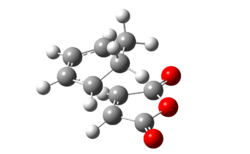

Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) of Transition State

To predict the structure that the reaction path from the transition structure will lead to, the Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) was calculated at the DFT/B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory involving 150 points and calculating force constants always. The results are shown in table 15 below.

Table 15: IRC of Transition State

| Energy/ Hartree | Total Energy Along IRC | Gradient Along IRC | Structure | Link to IRC calculations |

| -234.63915 |  |

|

|

DOI:10042/to-7215 |

As expected, cyclohexene was obtained as the minimum structure at the end of the reaction path, where the energy of the last few points in the IRC path form a plateau and the last point has a RMS gradient very close to zero. This further confirms that the transition state obtained earlier is the correct one for the Diels Alder reaction.

Activation Energies

To calculate the activation energies for the Diels Alder reaction, the transition structure was reoptimised at DFT/B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory, starting from the optimized structure obtained at the semi-empirical/AM1 level. A summary of the results obtained at the two different levels of theory is shown in table 16 below. The link to the transition state optimisations at DFT/B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory can be found here: DOI:10042/to-7185

Table 16: Summary of Energies

| AM1 | B3LYP/6-31G* | |||

| Electronic Energy/ Hartress | Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies/ Hartrees | Electronic Energy/ Hartress | Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies/ Hartrees | |

| at 298.15K | at 298.15K | |||

| TS | 0.11165 | 0.25945 | -234.54390 | -234.39691 |

| Butadiene | 0.04879 | 0.13949 | -155.98648 | -155.89644 |

| Ethylene | 0.02619 | 0.08025 | -78.58746 | -78.53319 |

| Reactants (Butadiene and Ethylene) | 0.07498 | 0.21974 | -234.57394 | -234.42963 |

The activation energies, ΔE, was then calculated by taking the difference between the energy of the reactants and the energy of the transition state. At 298.15K, the energy of the reactants is the sum of electronic and thermal energies. The results are shown in table 17 below.

Table 17: Activation Energies

| AM1 | B3LYP/6-31G* | |

| at 298.15K | ||

| ΔE | 24.92 | 20.53 |

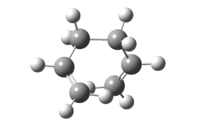

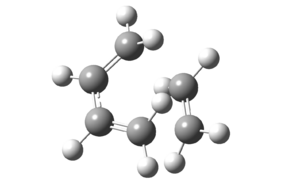

Reaction Between Cyclohexa-1,3-diene and Maleic Anhydride

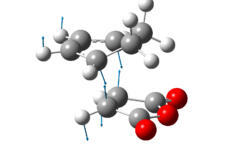

Optimisation of Transition States

Cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride were first optimised at the Semi-Empirical/AM1 level of theory and subsequently at a higher level of theory of DFT/B3LYP/6-31G*. The transition structures for the endo and exo products were optimised using TS(Berny) directly at both levels of theory as well. The results for the optimisation of transition states are shown in table 18 below.

Table 18: Optimisation of Transition States

| AM1 | B3LYP/6-31G* | |||

| Exo TS | Endo TS | Exo TS | Endo TS | |

| Jmol | ||||

| Image |  |

|

|

|

| Point Group | Cs | Cs | Cs | Cs |

| Energy/ Hartrees | -0.05042 | -0.05150 | -612.67931 | -612.68340 |

| Imaginary Frequency/ cm-1 | -813 | -806 | -448 | -447 |

| Image of Vibration at Imaginary Frequency/ cm-1 |  |

|

|

|

| Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies | 0.14488 | 0.14369 | -612.48766 | -612.49179 |

| Link to Transition State Optimisations | DOI:10042/to-7186 | DOI:10042/to-7187 | DOI:10042/to-7188 | DOI:10042/to-7189 |

As can be seen from the table above, the energy of the endo transition state is lower than that of the exo transition state, hence suggesting that the former is the more favourable transition state.

The presence of an imaginary frequency in the structures obtained shows that the structures obtained are transition states. In addition, the vibrations at the imaginary frequency illustrate that the bond formation process of the Diels Alder cycloaddition is synchronous.

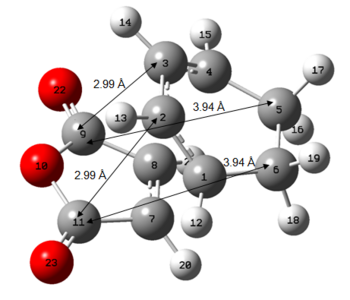

Geometry of Transition States

The key features of the geometry of the endo and exo transition states obtained at the DFT/B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory are shown in table 19 below. As most of the bond lengths are similar in both the exo and endo transition states, only those that are significantly different (i.e. the C-C through space distances between the -(C=O)-O-(C=O)- fragment of the maleic anhydrie and the "opposite" -CH2-CH2- and -CH=CH- fragments) are shown in the sketches below for clearer pictorial representations.

Table 19: Geometry of Exo and Endo Transition States

As can be seen from the results above, all the non-through space distances are very similar, including the bond forming or breaking distances for both the endo and exo transition states. As C5-C9/C6-C11 bond lengths in the exo transition state is 0.04Å longer than the C2-C11/C3-C9 bond lengths in the endo transition state, it seems that the endo transition state may experience a greater steric repulsion. However, the endo transition state has a lower energy than the exo transition state. Hence, the molecular orbitals of the transition states would be studied in an attempt to rationalise the lower energy of the endo transition state observed in table 18 above. In particular, the possibility of forming secondary orbital interactions would be investigated in a later section.

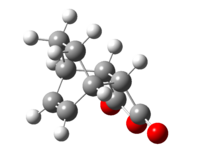

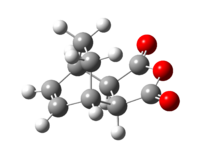

Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) of Transition States

To predict the structure that the reaction path from the endo and exo transition structures will lead to, the Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) was calculated at the Semi-Empirical/AM1 level of theory involving 150 points and calculating force constants always. The results are shown in table 20 below.

Table 20: IRC of Transition States

| Energy/ Hartree | Total Energy Along IRC | Gradient Along IRC | Structure | Link to IRC calculations | |

| Endo TS | -0.15991 |  |

|

|

DOI:10042/to-7216 |

| Exo TS | -0.16017 |  |

|

|

DOI:10042/to-7217 |

Both the endo and exo products were obtained from the endo and exo transition states respectively as minimum structures at the end of the reaction paths, where the energy of the last few points in the IRC path form a plateau and the RMS gradient of the final point was very close to zero. Again, this confirms that the transition states obtained earlier are correct.

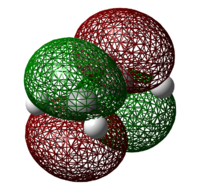

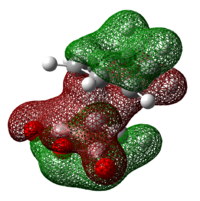

Molecular Orbitals of Transition States

In the Diels Alder cycloaddition reaction between 1,3-hexadiene and maleic anhydride, primary and secondary orbital interactions[6] may be involved as shown in Figure 4 below.

Figure 4: Primary and Secondary Orbital Interactions in Exo and Endo Transition States

As can be seen from Figure 4 above, there is a favourable secondary orbital overlap only in the endo transition state, where there is a good overlap between the anhydride fragment which has orbitals that are in the same phase as the diene orbitals at a distance of 2.99Å. This is not possible in the exo transition state due to spatial constraints where the relavant orbitals are at a distance of 3.88Å.

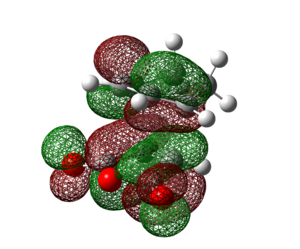

The key molecular orbitals of the exo and endo transition states obtained at the DFT/B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory are shown in tables 21 and 22 below.

Table 21: Molecular Orbitals of Exo Transition State

| HOMO | LUMO | |

| Molecular Orbital |  |

|

| Energy/ Hartrees | -0.24214 | -0.07842 |

Table 22: Molecular Orbitals of Endo Transition State

| HOMO | LUMO | HOMO-10 (Orbital 37) | HOMO-19 (Orbital 28) | |

| Molecular Orbital |  |

|

|

|

| Energy/ Hartrees | -0.24229 | -0.06773 | -0.39956 | -0.49400 |

Examining the HOMO of the exo and endo transition states, it can be seen that there is a clear nodal plane between the -(C=O)-O-(C=O)- fragment and cyclo-1,3-hexadiene in both transition states. A key difference is that in the endo transition state, there is a large π orbital hovering right above the carbonyl carbons of the -(C=O)-O-(C=O)- fragment whereas in the exo transition state, the large π orbital is right above space. This shows that secondary orbital overlap is possible in the endo transition state but not in the exo transition state. The secondary orbital overlap in the endo transition state can be seen in the HOMO-10 orbital (orbital 37) and HOMO-19 orbital (orbital 28) of the endo isomer in table 22 above, where the p orbitals of the carbonyl carbons interact with the p orbitals of the carbons of the "opposite" -CH=CH- fragment. Such an overlap results in the overall stabilisation of the endo isomer.

Activation Energies

To calculate the activation energies for the Diels Alder reaction, a summary of the optimisation results obtained at the two different levels of theory is shown in table 23 below.

Table 23: Summary of Energies

| AM1 | B3LYP/6-31G* | |||

| Electronic Energy/ Hartress | Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies/ Hartrees | Electronic Energy/ Hartress | Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies/ Hartrees | |

| at 298.15K | at 298.15K | |||

| Exo TS | -0.05042 | 0.14488 | -612.67931 | -612.48766 |

| Endo TS | -0.05150 | 0.14369 | -612.68340 | -612.49179 |

| Cyclo-1,3-hexadiene | 0.02771 | 0.15773 | -233.41894 | -233.29093 |

| Maleic Anhydride | -0.12182 | -0.05819 | -379.28954 | -379.22848 |

| Reactants (Cyclo-1,3-hexadiene and Maleic Anhydride) | -0.09411 | 0.09954 | -612.70848 | -612.51941 |

The activation energies, ΔE, was then calculated by taking the difference between the energy of the reactants and the energy of the transition states. At 298.15K, the energy of the reactants is the sum of electronic and thermal energies. The results are shown in table 24 below.

Table 24: Activation Energies

| AM1 | B3LYP/6-31G* | |

| at 298.15K | ||

| ΔE (Exo TS) | 28.45 | 19.92 |

| ΔE (Endo TS) | 27.70 | 17.33 |

As can be seen from table 24 above, the activation energy of the endo transition state is lower than that of the exo transition state. Hence, the endo transition state is the kinetic product of the reaction.

Conclusion

The calculations performed have been successful in predicting the transition states of the Diels Alder cycloaddition reaction. The study of molecular orbitals has also helped to explain the selectivity of the reaction by determining the relevant orbital overlaps; it can also elucidate certain unique stabilisation effects such as the secondary orbital overlap interactions. By investigating the energy of the transition states, the activation energies can be obtained to predict the selectivity of the reaction as well by determining the kinetic product observed. However, such prediction of the selectivity of the reaction was performed based on prior knowledge that the kinetic product predominates.

Due to time constraints, there are certain effects that have been neglected in the calculations. Firstly, the effects of high pressure on Diels-Alder reactions[7] was not investigated. In addition, while the Diels Alder reactions investigated in this exercise are all under thermal conditions, light-induced Diels Alder reactions[8] could be investigated as well.

References

- ↑ B. G. Rocque, J. M. Gonzales, H. F. Schaefer III, Mol. Phys., 2002, 100, 441. DOI:10.1080/00268970110081412

- ↑ J. B. Foresmann, A. Frisch, Exploring Chemistry with Electronic Structure, Gaussian Inc., Pittsburgh, 2nd Ed., 1993, pp. 61.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 M. J. Goldstein, M. S. Benzon, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1972, 94, 7147. DOI:10.1021/ja00775a046

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 F. H. Allen, O. Kennard, D. G. Watson, L. Brammer, A. G. Orpen, R. Taylor, J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2, 1987, S1. DOI:10.1039/P298700000S1

- ↑ A. Bondi, J. Phys. Chem., 1964, 68, 441. DOI:10.1021/j100785a001

- ↑ J. I. Garcia, J. A. Mayoral, L. Salvatella, Acc. Chem. Res., 2000, 33, 658. DOI:10.1021/ar0000152

- ↑ K. Afarinkia, M. J. Bearpark, A. Ndibwami, J. Org. Chem., 2003, 68, 7158. DOI:10.1021/jo0348827

- ↑ B. Heinz, S. Malkmus, S. Laimgruber, S. Dietrich, C. Schulz, K. Rück-Braun, M. Braun, W. Zinth, P. Gilch, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2007, 129, 8577. DOI:10.1021/ja071396i