Rep:Mod:phys3ec1412

Abstract

The present computational study involves the analysis of the Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene, and the Diels-Alder cycloaddition reaction between ethylene and cis-butadiene using the GaussView software (It is actually the Gaussian software that is doing the computation in the background, Gaussview builds the input and reads the output of Gaussian. João (talk) 20:44, 20 April 2015 (BST)). In the study of the Cope rearrangement process, computations done using the Hatree Fock method (HF/3-21G level of theory) showed that 1,5-hexadiene has a total of 10 energetically distinct conformations, with the most stable conformer being the gauche-3 conformer. Reoptimisation of the anti-2 conformer using the DFT method, which involves a higher B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory gave a lower and more accurate energy value (Why is lower energy more accurate? João (talk) 20:44, 20 April 2015 (BST)) relative to the Hatree Fock method. Subsequently, optimisation of both the chair and boat transition states was done, and the chair transition state was shown to be relatively lower in energy. Hence, it was concluded that the Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene goes through a more favorable chair transition state.

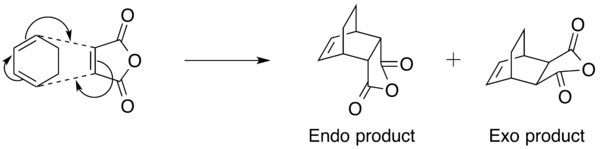

In the study of the Diels-Alder cycloaddition reaction, the transition state of the reaction between cis-butadiene and ethylene was first optimised using the AM1 semi-empirical molecular orbital method. It was shown from the vibrations that the Diels-Alder reaction indeed follows a concerted mechanism, and the success of the reaction is solely dependent on the extent of the molecular orbital overlap between the diene and dienophile. Subsequently, the effect of substituents on the regioselectivity of the Diels-Alder reaction was explored using cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride. It was shown that the endo transition state of the reaction is energetically more stable than the exo transition state, and this is largely attributed to the more pronounced secondary orbital stabilising interactions between the two reactants exhibited in the endo transition state.

Introduction

Computational chemistry is an important branch of chemistry, and it is perhaps one of the most powerful tools that chemists have in their arsenal to understanding the chemical properties of compounds, as well as the mechanisms and reaction rates of chemical reactions.[1] This not only allows experimental chemists to better appreciate the experimental data obtained from their experiments, but also enables theoretical chemists to model unknown chemical reactions that may not be readily performed experimentally. Evidently, computational chemistry provides many key advantages to the traditional way of running experiments, and is being increasingly valued in both the chemical manufacturing industry and the pharmaceutical industry.[2,3]

A large range of computational chemistry methods today makes use of first principles from quantum chemistry, and these methods are more aptly known as "Ab initio" (latin for "from the beginning").[4] Two excellent examples of these "Ab initio" methods include the Hatree-Fock (HF) method, and the Density functional theory (DFT) method. These methods will be used in this computational study via the Gaussview software to analyse two different pericyclic reactions, namely the Cope rearrangement reaction and the Diels-Alder cycloaddition reaction. The study of the Cope rearrangement was done using 1,5-hexadiene, and it involves the optimisation of the transition structures of the rearrangement process to determine the more favoured reaction mechanism. The Diels-Alder cycloadditon reaction on the other hand was studied using cis-butadiene and ethylene, and it involves analysing the symmetry of the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of the transition state, to determine the effect of symmetry on the success of the pericyclic reaction. In addition, the regioselectivity of the Diels-Alder reaction was also studied with the use of cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride. The discussion of the two different pericyclic reactions will be presented in the same order as described.

The Cope Rearrangement

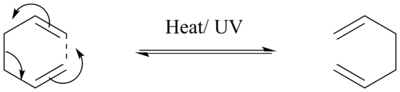

The Cope rearrangement, named after its inventor Arthur C. Cope (Can chemical reactions be "invented", or they occur because they are thermodynamically allowed? João (talk) 20:44, 20 April 2015 (BST)), is characterised by a [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement of 1,5-dienes.[5] As with any other pericyclic reaction, it follows a concerted mechanism (Figure 1) and this means that bonds are being broken and made in a single step that involves no reaction intermediates.

It is widely accepted today that the Cope rearrangement proceeds via either a "Chair" or a "Boat" transition state, with the "Chair" transition state being favoured as it is relatively more stable in energy. In this part of the experiment, we will be attempting to ascertain this by performing Gaussian calculations of the different structures involved in the rearrangement process of 1,5-hexadiene using the Gaussview software(version 5.0). The discussion will be presented in the following order- optimisation of the reactants and products of the rearrangement reaction, and optimisation of the "Chair" and "Boat" transition states.

Optimisation of the reactants and products

The first part of the experiment involves the structural optimisation of 1,5-hexadiene. The stereochemistry of 1,5-hexadiene can be categorised into two major types of conformations, namely the anti and gauche conformers. The anti conformers have a dihedral angle between ±90° and 180°, while the gauche conformers have a dihedral angle of ±60°. We started the experiment off by drawing 1,5-hexadiene in an approximate anti conformation, and the structure was subsequently cleaned and optimised using the HF/3-21G level of theory. The results of the Gaussian calculations for this conformer are shown below.

Energy= -231.69253528 hartree

Dipole moment= 0.0000 D

Point group= Ci

This anti conformer was then identified to correspond to the anti-2 conformer (Table 1). The next step of the experiment was to draw an approximate gauche conformation of 1,5-hexadiene, and optimising it using the same HF/3-21G level of theory. The purpose of this was to compare the energy values of the gauche conformation with the anti conformation. It was expected for the gauche conformation to have a higher energy than the anti conformation due to the relatively bulkier vinyl-containing R groups being closer to each other, and we would therefore expect greater steric repulsions that destabilse the gauche conformation. The results of the Gaussian calculations for this conformer are shown below.

Energy= -231.69266121 hartree

Dipole moment= 0.3407 D

Point group= C1

This gauche conformer was later identified to be the gauche-3 conformer (Table 1). Interestingly, the energy obtained for the gauche conformer shows a relatively lower value than that obtained for the anti conformer. This was unexpected, and it can be attributed to the stabilising stereoelectronic interactions between the π-molecular orbital of one vinyl group with the C-H orbital of the opposite vinyl group, present only in the gauche-3 conformation. This stabilising stereoelectronic interaction overcompensates the destablising steric interactions between the pair of vinyl groups, thus resulting in a lower energy relative to the anti conformation. In fact, the gauche-3 conformer was subsequently found to be the lowest energy conformer of 1,5-hexadiene. A total of ten different conformers with varying distinct energies and symmetry groups was obtained in this computational study (Table 1), and this is in good agreement with that reported by Gunget al.[6] While it is statistically possible for 1,5-hexadiene to adopt twenty-seven different conformations due to it having three freely rotating C-C bonds with three rotational minima, some of these conformations are similar in energy or symmetry and are hence not illustrated in the discussion. (Even if these other conformations were merely to have a similar energy or be of the same point group energy as the conformations that you register, would there be any reason why you should not compute their geometry? More importantly, are these other conformations distinguishable from the structures you report? João (talk) 20:44, 20 April 2015 (BST))

| Conformer | 3D-Structure | Point group | Dipole moment/D | Energy/Hartrees HF/3-21G | Relative Energy/ kcalmol-1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-1 | C2 | 0.2021 | -231.69260235 | 0.04 | |||

| Anti-2 | Ci | 0.0000 | -231.69253528 | 0.08 | |||

| Anti-3 | C2h | 0.0002 | -231.68907066 | 2.25 | |||

| Anti-4 | C1 | 0.2948 | -231.69097051 | 1.06 | |||

| Gauche-1 | C2 | 0.4554 | -231.68771616 | 3.10 | |||

| Gauche-2 | C2 | 0.3805 | -231.69166702 | 0.62 | |||

| Gauche-3 | C1 | 0.3407 | -231.69266121 | 0.00 | |||

| Gauche-4 | C2 | 0.1281 | -231.69153032 | 0.71 | |||

| Gauche-5 | C1 | 0.4439 | -231.68961574 | 1.91 | |||

| Gauche-6 | C1 | 0.5361 | -231.68916020 | 2.20 |

It can be observed that the ten different conformers of 1,5-hexadiene are energetically distinct, with subtle differences in their energies. The energy difference between the different conformers is subtle because it only involves a rotation of the flexible sp3 hybridised C-C bonds. To better appreciate and explain how these differences in energy come about, we need to consider the stereoelectronic interactions present in the different conformers. and this is best achieved by looking at the Newman projections of the different conformers (Figure 2).

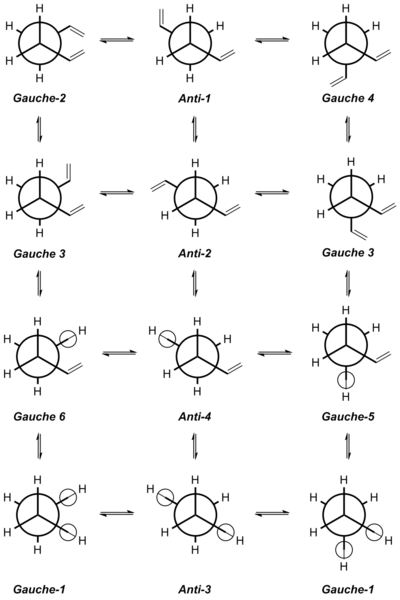

The Newman projections are drawn in reference to the study done by Rocque et al.,[7] and they are assigned accordingly to the conformers shown previously (Table 1) based on comparison of the dihedral angles. A total of twelve different Newman projections are shown, with the Gauche-3 and Gauche-1 conformers possessing a pair of energetically similar enantionmers each. The three conformers in the first row- gauche-2, anti-1 and anti-4, were obtained by rotation about the central sp3 C-C bond of 1,5-hexadiene with the pair of vinyl groups antiparallel to each other. The three conformers in the second row- Gauche-3a, anti-2, and Gauche-3b, were also obtained by rotation about the central sp3 C-C bond of 1,5-hexadiene, but with the pair of vinyl groups now parallel to each other. The three conformers in the third row- Gauche-6, Anti-4, and Gauche-5 were obtained by rotation about the central sp3 C-C bond, while keeping one of the Csp3-Csp2 bonds in an s-cis orientation. Lastly, the conformers Gauche-1a, Anti-3, and Gauche-1b were obtained by having both of the Csp3-Csp2 bonds fixed in an s-cis orientation when rotating about the central sp3 C-C bond.

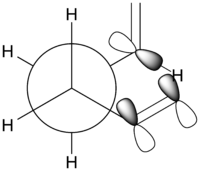

As mentioned earlier, the Gauche-3 conformer is the most energetically-stable conformer of 1,5-hexadiene due to the stabilising stereoelectronic interactions between the C-H orbital of one vinyl group, with the π-molecular orbital of the opposite vinyl group. This is better illustrated with an enlarged Newman projection showing the relevant stabilising molecular orbital interactions (Figure 3) (Do you see evidence for this effect in the molecular orbitals you calculate? João (talk) 20:44, 20 April 2015 (BST)). Even though the destabilising steric repulsions between the vinyl groups are larger in the Gauche-3 conformer relative to the Anti conformers, the stabilising effect is more pronounced and therefore overcompensates the destabilising repulsions to make it the most energetically-stable conformer of 1,5-hexadiene.

The Anti-1 and Anti-2 conformers are the second most energetically-stable conformers of 1,5-hexadiene, and this can be attributed to the ease of the destabilising steric repulsions between the relatively bulky vinyl groups by having the vinyl groups adopting an anti-periplanar conformation. However, these conformers are still relatively higher in energy and less stable than the Gauche-3 conformer due to the absence of the stabilising interactions mentioned earlier. The next two conformers in line (in terms of stability) are the Gauche-2 and Gauche-4 conformers, which are higher in energy due to the pair of vinyl groups being brought closer to each other. As a result, a significant amount of steric repulsions is now present between the vinyl protons of carbon 2 and carbon 5, as evident from the reduced H-H distance of 2.7Å and 3.4Å in the Gauche-2 and Gauche-4 conformers respectively. This is in contrast to the Anti conformers, which showed a H-H distance of more than 4.0Å between the vinyl protons of carbon 2 and carbon 5. Hence, this explains why the Gauche-2 and Gauche-4 conformers are relatively higher in energy.

Following these five conformers are the conformers with either one or both of the Csp3-Csp2 bonds arranged in an s-cis orientation. These conformers are significantly higher in energy due primarily to the increased steric hindrance between the vinyl protons, which are brought even closer to each other as a result of the s-cis orientation. Within this group of energetically less stable conformers, the anti-4 conformer is the most stable due to it having only one s-cis oriented Csp3-Csp2 bond with the opposite vinyl group being in an anti-periplanar conformation. This is followed by the two gauche conformers- Gauche-6 and Gauche-5 having one s-cis oriented Csp3-Csp2 bond. These Gauche conformers have a relatively higher energy than the anti-4 conformer due to the greater steric repulsions between the vinyl groups, which are brought closer to each other due to the gauche conformation. This is evident from the reduced distance of 2.9Å and 2.6Å between the vinyl groups of Gauche-6 and Gauche-5 respectively, as compared to that of the Anti-4 conformer, which has a greater distance of >4.0Å between the vinyl groups. The conformers of 1,5-hexadiene with the highest energy are those with both of the Csp3-Csp2 bonds arranged in an s-cis orientation, and the reason for this has been previously discussed. Similarly, the Gauche-1 conformers are energetically less stable than the Anti-3 conformers due to the greater steric repulsions between the vinyl groups. Evidently, the extent of the steric repulsions between the vinyl groups plays an important factor in determining the relative energies of the conformers.

Reoptimisation of Anti-2 conformer using DFT method

Following the successful analysis of the different conformers of 1,5-hexadiene using the Hatree-Fock method, we proceeded to use the DFT method to reoptimise the calculations for the Anti-2 conformer. The Anti-2 conformer was chosen to be reoptimised because it will be used for subsequent optimisation calculations of the "Boat" transition state. Using the HF/3-21G-optimised structure of the Anti-2 conformer, optimisation using the B3LYP/6-31G* level was done and the results of the Gaussian calculations are shown below.

Energy= -234.61171063 hartree

Dipole moment= 0.0000

Point group= Ci

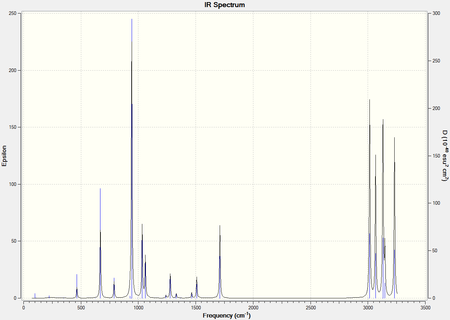

It was observed that optimisation calculations of the Anti-2 conformer using the DFT method gave a significantly lower energy value than the Hatree-Fock method, and this shows that the DFT method is a more accurate method for optimising the structure of the conformer (Why is the lower energy result more accurate? You are comparing different methods, how do you know that DFT does not systematically give you an underestimate of the energy value? The absolute value of the energy is not accessible to experiments, so one cannot meaningfully compare absolute values of the energy. João (talk) 20:44, 20 April 2015 (BST)). It was also observed that both the DFT and the Hatree-Fock methods registered the same symmetry point group of Ci for the Anti-2 conformer of 1,5-hexadiene. However, this may not necessarily imply that the geometries of the two optimised structures are the same, as the geometries are also dependent on other factors such as the bond lengths of the molecule (That is correct. So, in the end how do the geometries compare to each other? João (talk) 20:44, 20 April 2015 (BST)). Frequency calculations of the Anti-2 conformer were also done using the DFT method, which predicts the different vibrations present in the conformer and then produces an IR spectrum of it (Figure 4). This will then allow us to draw comparisons between the computational results and the experimental values to determine the accuracy of the computational study.

From the IR spectrum, it can be observed that all the frequencies present in the optimised Anti-2 conformer structure are of real and positive values. The absence of negative frequency values prove that the optimised structure obtained is indeed at mimimum energy rather than being at a transition state. In addition, all of the expected vibrational peaks of 1,5-hexadiene are shown in the IR spectrum- C-H bond stretches appear around the 3000-3250cm-1 region, and C=C bond stretches are shown at 1700cm-1. Evidently, the DFT method is accurate in optimising the structure of the Anti-2 conformer of 1,5-hexadiene, as well as predicting the frequencies present in the molecule.

In addition to providing information about the frequencies of the molecule, the Gaussian calculations using the DFT method also provided useful information (It is not the DFT calculation per se that gives you this information, but rather the fact that you did a frequency calculation. Had you done a frequency calculation with the Hardtree-Fock method you would obtain the same information - different values though. João (talk) 20:44, 20 April 2015 (BST)) about the thermodynamic properties of the molecule. Some of these values calculated include the following:

i) Sum of electronic and zero-point energy (E = Eelec + ZPE)

ii) Sum of electronic and thermal energy (E = Eelec + Etrans + Evib + Erot)

iii) Sum of electronic and thermal enthalpies (H = Helec + Htrans + Hvib + Hrot)

iv) Sum of electronic and thermal free energies (G = Gelec + Gtrans + Gvib + Grot).

Calculations of these values were done for the Anti-2 conformer at both 0K and 298.15K, to investigate the effect of temperature on the energy mimima of the conformer. The results are as shown below (Table 2).

| Thermodynamic property | Value at 0K/ hatrees | Value at 298.15K/ hatrees |

|---|---|---|

| E = Eelec + ZPE | -234.469216 | -234.469216 |

| E = Eelec + Etrans + Evib + Erot | -234.469216 | -234.461864 |

| H = Helec + Htrans + Hvib + Hrot | -234.469216 | -234.460920 |

| G = Gelec + Gtrans + Gvib + Grot | -234.469216 | -234.500812 |

The first observation that could be made from the calculation results is that the sum of electronic and zero-point energies ( E = Eelec + ZPE) are equivalent at both 0K and 298.15K, and this is expected because this value is indicative of the minimum energy that the conformer has on the bare potential energy surface, which is independent of temperature. Secondly, it was observed that the sum of electronic and thermal energy (E = Eelec + Etrans + Evib + Erot) is more positive at 298.15K than at 0K. This is in good agreement with theory as there is less heat energy at 0K relative to 298.15K, and we would therefore expect the conformer to possess more energy (less stable) at 298.15K. In fact, the amount of thermal energy (Etrans + Evib + Erot) that the conformer possesses at 0K is effectively 0J, as we know from theory that all molecular motions come to a stop at absolute zero temperature. This is evident by how the calculated value of (E = Eelec + Etrans + Evib + Erot) is the same as (E = Eelec + ZPE) at 0K. Similarly, it was observed that the sum of electronic and thermal enthalpies of the conformer at 298.15K has a more positive value than at 0K. This can be attributed to the fact that the heat capacity of the conformer is effectively 0 at 0K, due to trapping of the ground state in the energy well due to negligible heat energy for promotion to a higher energy state. As enthalpy has a direct relationship with the heat capacity of the molecule, the enthalpy energies of the conformer at 0K is hence of a less positive value than that at 298.15K. Lastly, it was observed that the Gibbs free energy of the conformer (G = Gelec + Gtrans + Gvib + Grot) has a more positive value at 0K than at 298.15K. The Gibbs free energy is essentially a measure of the amount of work that the system can achieve, and is given by the equation: G= H-TS. Hence, the results obtained here appear to be in good agreement with the equation as while the 'TS' term in the equation is effectively 0 at 0K (resulting in the enthalpy and Gibbs free energy of the conformer to be similar at 0K), it is of a positive value at 298.15K, and this results in the overall Gibbs free energy to take up a less positive value (lower energy) at 298.15K than at 0K.

Optimisation of the Chair transition state

In the next part of this computational experiment, we will be attempting to optimise the Chair transition state structure of the Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene. This can be done via two different methods; the first method is known as the Hessian method and it involves computing the force constant matrix using a relatively well-guessed structure of the Chair transition state. The second method is known as the frozen coordinates method and as its name implies, involves freezing the atoms or bond lengths of the Chair transition state at specific coordinates. The discussion of the results of these two methods will be further discussed in the following paragraphs.

Using the Hessian method, two optimised allyl (CH2=CH=CH2) fragments were drawn to produce a guess structure for the Chair transition state, which gave an interatomic distance of approximately 2.20Å between the terminal carbons of the allyl fragments (2.29Å and 2.20Å). Subsequently, the guess structure was optimised to a transition state (Berny) using the HF/3-21G level of theory, and the results of the Gaussian calculations are shown below.

Energy= -231.61932246 hartree

Dipole moment= 0.0004 D

Point group= C2h

Terminal carbon-carbon distances: 2.02Å, 2.02Å

An interesting observation was made when looking at the vibrational frequencies data of the optimised Chair transition state- a negative vibrational frequency at -817.93 cm-1 was present. The negative frequency value is an indication that the optimised structure lies at the maximum of the bare potential energy surface along a specific axis, and this hence proves that a transition state has been reached. These vibrations of the optimised Chair transition state are as shown below (Figure 5).

Following the use of the Hessian method, we proceeded on to optimise the guess structure of the Chair transition state using the frozen coordinates method. As mentioned earlier, this method involves freezing the coordinates of the terminal carbons of the allyl fragment pair as these carbons are involved in the formation or breaking of bonds during the Cope rearrangment. Subsequently, the structure was optimised using the HF/3-21G level of theory, and the results of the Gaussian calculations are shown below. (It is not clear what you did: you froze the terminal bond length and then optimized the structure. Are the final bond distances the same as you had in the beginning? Are they optimized? João (talk) 20:44, 20 April 2015 (BST))

Energy= -231.61932247 hartree

Dipole moment= 0.0001 D

Point group= C2h

Terminal carbon-carbon distances: 2.02Å, 2.02Å

Evidently, the frozen coordinate method produced largely the same results as that of the Hessian method. The negative vibrational frequency at -817.93 cm-1 was also registered using the frozen coordinate method. Hence, it can be concluded that both methods were successful in giving us the optimised structure of the Chair transition state, as the results obtained were reproducible in either method.

Optimisation of the Boat transition state

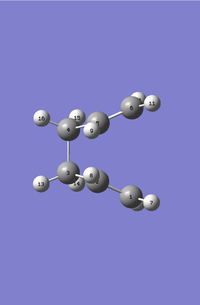

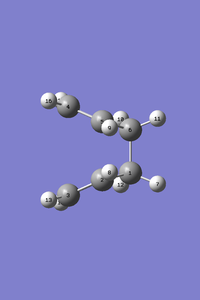

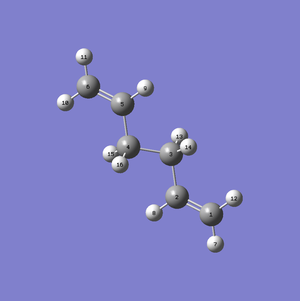

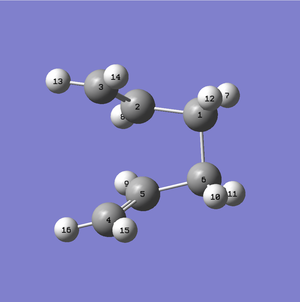

The next part of this computational experiment was to optimise the Boat transition state of the Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene using the QST2 method. This method is in contrast to the two methods used previously for the optimisation of the Chair transition state, as it involves having the reactant and product of the Cope rearrangement as inputs for the optimisation calculations rather than using a guess structure. As mentioned earlier, the Anti-2 conformer was chosen as the reactant input for the Boat transition state optimisation calculations. The product input also adopts the Anti-2 conformation, but the difference between the product and reactant is that the atoms have now changed positions as shown below (Figure 6).

b)

b)

Optimisation of the Boat transition was done using these input structures at the HF/3-21G level of theory, and the result of the Gaussian calculations is shown (Figure 7). It can be observed that the structure of the transition state obtained does not correspond to the Boat transition state, but rather a more dissociated form of the Chair transition state. The reason for this failure is that the program was not able to acknowledge the possibility of the central bond rotating, and what it did was to only translate the allyl fragments. It was hence self-evident that the Boat transition state structure was not achievable with the use of these input reactant and product structures.

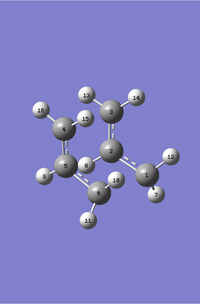

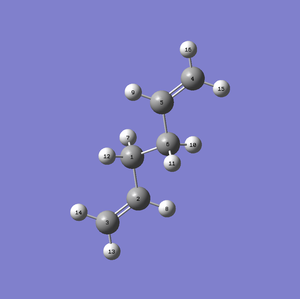

Consequently, the reactant and product input structures were corrected by changing the dihedral angle of the central four carbon atoms (C2-C3-C4-C5 of the reactant and C2-C1-C6-C5 of the product) to 0o instead of the initial 180o, and then reducing the angle between the inside carbons (reactant: C2-C3-C4, C3-C4-C5; product: C2-C1-C6, C1-C6-C5) to 100o (Figure 8). The reason for doing so is that it helps to generate structures that resemble the Boat transition state more closely, and hence aids the program in generating the correct transition state.

b)

b)

As expected, the corrected input structures of the reactant and product were successful in generating the Boat transition state of the Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene (Figure 9). The energy of the transition state was determined to be -231.60280249 hatrees, with a point group of C2v and a interatomic distance of 2.14Å between the carbon atoms. In addition, the transition structure obtained also gave a imaginary vibrational frequency of -839.96cm-1, and this ascertains that a transition state has indeed been achieved.

Evidently, the use of the QST2 method has its limitations as there is a high possibility of it failing to give the correct transition state structure if the input structures of the reactant and product are not similar enough. A more effective method will be the QST3 method, which allows the input of the geometry of a guess transition state structure. The input structures for the QST3 method are shown below (Figure 10). (By running the QST3 method in this way with the modified "reactants" and "products", do you have any advantage over the QST2? João (talk) 20:44, 20 April 2015 (BST))

The Boat transition state structure was successfully obtained using the QST3 method (Figure 11), and the energy of the transition state was determined to have a value of -231.60280247 hatrees, with a point group of C2v and a interatomic distance of 2.14Å between the carbon atoms. Furthermore, a similar imaginary frequency of -839.92cm-1 was also observed from the structure obtained, and this implies that a transition state has indeed been achieved. These results are in near perfect agreement with that obtained from the QST2 method, with only a very minute difference in the energy of the transition state at the 8th decimal place. Hence, this shows that the results are reproducible using either method, and the Boat transition state structure has been generated successfully.

Linking conformers to the transition state structures

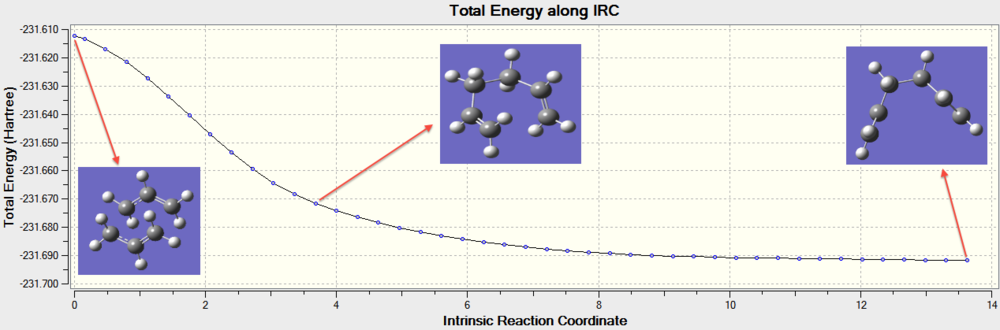

Even though we have successfully optimised both the Chair and Boat transition state structures of 1,5-hexadiene undergoing the Cope rearrangement, we have yet to determine which of the ten energetically distinct conformers of 1,5-hexadiene these transition states will lead to. In order for us to do this, the Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) method was used. The IRC method essentially enables us to track the trajectory of the transition state as it moves along a minimum energy path to the local minimum on the potential energy surface. The IRC calculations were done on the Chair transition state at the HF/3-21G level of theory, and the results are shown below (Figure 12).

The energy of the conformer given at the end of the IRC calculations was shown to have a value of -231.69160312 hartrees, with a symmetry point group of C2. This corresponds to the Gauche-2 conformer as shown previously (Table 1). The result obtained is different from expected, as we know from previous calculations that the lowest energy conformer of 1,5-hexadiene is actually the Gauche-3 conformer. Hence, we would then expect the IRC calculations to yield the Gauche-3 conformer as the local minimum on the potential energy surface (Why did you expect to obtain gauche-3? Isn't gauche-2 a valid local minimum? What is an IRC, or how is it computed? João (talk) 20:44, 20 April 2015 (BST)). In recognition of this anomaly, we attempted to improve the IRC calculations by using the three different methods as highlighted below:

(Why would any of these methods give you a different final conformation from the one you obtained? João (talk) 20:44, 20 April 2015 (BST))

i) Optimisation to a minimum of the final structure obtained from the previous IRC calculations

ii) Running a new IRC calculation with a larger number of points

iii) Running a new IRC calculation while specifying for it to compute the force constants at every step

Method (i) was tested out, but it unfortunately yielded the same Gauche-2 conformer structure at the end of the calculations. Method (ii) was done by increasing the number of points from 50 in the previous calculations to 200. However, this too gave the same Gauche-2 conformer structure. Method (iii) was not implemented as it was already specified during the previous calculations for the force constants to be computed at every step. Evidently, the IRC calculations have failed to generate the Gauche-3 conformer structure as the local minimum on the potential energy surface. The reason for this might be because the IRC calculations are convergent, or that the energy difference between the Gauche-2 and Gauche-3 conformers are too small to be resolved successfully by the IRC method.

Calculation of activation energies

The last part of this discussion on the Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene is the calculation of the activation energy required for the pericyclic reaction to go through. This is achieved by calculating the sum of the electronic and thermal energies of both the Chair and Boat transition states, and then calculating the difference between these values to that of the starting Anti-2 conformer (Table 2). The calculations were done using the higher B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory (Did you reoptimise the transition state geometry or just calculated the energy on the previously optimised geometry using a different level of theory? How do you know that you still have a transition state at a different level of theory? João (talk) 20:44, 20 April 2015 (BST)) to ensure a fair comparison with the energy values of the Anti-2 conformer, which was obtained using the same method. In addition, the calculations were done at both 0K and 298.15K to investigate the effect of temperature on the activation energies. The results of the Gaussian calculations are shown below (Table 3).

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic energy | Sum of electronic and zero-point energies | Sum of electronic and thermal energies | Electronic energy | Sum of electronic and zero-point energies | Sum of electronic and thermal energies | |

| at 0 K | at 298.15 K | at 0 K | at 298.15 K | |||

| Chair TS | -231.61932247 | -231.466700 | -231.461340 | -234.55698325 | -234.414921 | -234.408996 |

| Boat TS | -231.60280249 | -231.450928 | -231.445299 | -234.54308982 | -234.402338 | -234.396002 |

| Anti-2 reactant | -231.69253528 | -231.539539 | -231.532565 | -234.61171063 | -234.469216 | -234.461864 |

Using the values obtained, the activation energies that the Anti-2 reactant requires at 0K/298.15K to reach the Chair and Boat transition state were calculated by taking the difference between their sums of electronic and zero-point energies (for 0K calculations), or the difference between their sums of electronic and thermal energies (for 298.15K calculations). The results are shown below (Table 4), with the energies being converted from "hartree" to "kcal/mol" for easier reference (1 hartee= 627.509kcal/mol).

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | Expt. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| at 0 K | at 298.15 K | at 0 K | at 298.15 K | at 0 K | |

| ΔE (Chair) | 45.71 | 44.69 | 34.07 | 33.18 | 33.5 ± 0.5 |

| ΔE (Boat) | 55.60 | 54.76 | 41.97 | 41.33 | 44.7 ± 2.0 |

From the values of the activation energies obtained, it can be observed that less energy is required for the starting Anti-2 reactant to reach the Chair transition state relative to the Boat transition state, and this proves that the transition state is indeed more stable in the Chair conformation than the Boat conformation. Furthermore, the activation energies obtained from the computations are in good agreement with the experimental values, and this demonstrates that computational methods are indeed a valuable and reliable way of understanding chemical reactions, in this case the Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene.

The Diels-Alder reaction

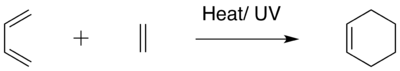

In the next part of this computational experiment, we will be looking at the Diels-Alder cycloaddition reaction- a highly useful synthetic method for making substituted cyclohexene compounds. Similar to the Cope rearrangement as previously discussed, the Diels-Alder is a pericyclic type reaction, and it involves the concerted [4+2] cycloaddition reaction between an electron-rich conjugated diene and a substituted alkene acting as the dienophile.[8] In the following sections, we will first be looking at the Diels-alder reaction between ethylene and butadiene. Subsequently, we will be investigating the regioselectivity of the Diels-Alder reaction by using a substituted diene and dienophile, namely cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride.

Diels-Alder reaction between ethylene and cis-butadiene

As mentioned, the Diels-Alder cycloaddition reaction between ethylene and cis-butadiene follows a concerted mechanism (Figure 13). The key factor that determines the success of the reaction is the extent of overlap between the molecular orbitals of the two reactants. Essentially, the HOMO of one reactant must be able to overlap favorably with the LUMO of the other reactant and vice-versa, for the reaction to occur. This extent of overlap is in turn determined by the symmetry of these molecular orbitals, where a favorable overlap is driven by the respective HOMO/LUMO pairs having similar symmetries. Hence, we will be focusing our study of this reaction by finding and comparing the symmetries of these HOMO/LUMO pairs.

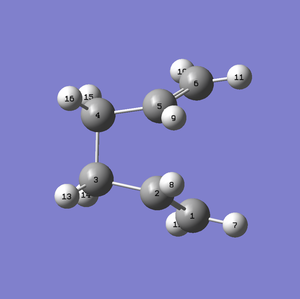

We started off the study by optimising the geometry and structure of cis-butadiene using the AM1 semi-empirical molecular orbital method. The energy of the optimised cis-butadiene structure was found to have a value of 0.04879730 a.u., while the symmetry point group of the structure is C2v. The optimised structure of cis-butadiene is as shown below (Figure 14).

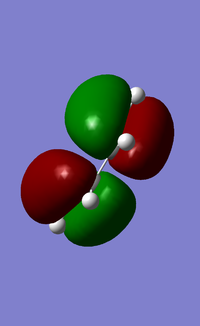

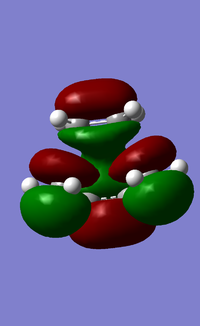

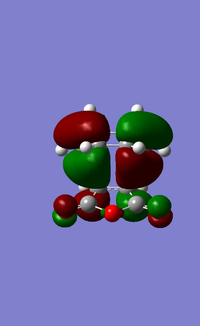

In addition, the HOMO and LUMOs of the optimised cis-butadiene structure were also visualised as shown below (Figure 15). Evidently from the diagram, the HOMO and LUMOs of cis-butadiene are quite simple and relatively easy to understand. The HOMO of cis-butadiene is anti-symmetrical to the plane of symmetry perpendicular to the molecule, while the LUMO is symmetrical to the same plane of symmetry.

b)

b)

Following the optimisation of cis-butadiene, we proceeded on to optimise the geometry of the transition state involved in the Diels-Alder reaction between ethylene and cis-butadiene. A guess structure of the transition state was first drawn, and the distance between the terminal carbons between ethylene and cis-butadiene was set to 2.20Å using the frozen coordinates method. As previously described in the previous section on the Cope rearrangement, the frozen coordinate method involves freezing the coordinates of the carbon atoms that are involved in the formation of the new bonds between ethylene and cis-butadiene. Optimisation the a transition state (Berny) was subsequently run using the AM1 semi-empirical method, and the results are shown below.

Energy= 0.11165473 a.u.

Dipole moment= 0.5608

Point group= Cs

Terminal C-C distances= 2.12A, 2.12A

The results obtained are in good agreement with what we would expect of the transition state. The interatomic distance between the terminal C-C bonds between ethylene and cis-butadiene have decreased from 2.20Å to 2.12Å (How does this distance compare with twice the van der Waals radius for carbon? Why might that be significant? João (talk) 11:39, 21 April 2015 (BST)), and this implies that the ethylene and cis-butadiene molecules have moved closer to each other for the reaction to occur. In addition, the pair of C=C bonds in butadiene have shown a visible increase in length (1.34Å to 1.38Å), signifying a weakening of the double bonds as the reaction proceeds. This was also reflected in the ethylene molecule, where its C=C bond length increases from 1.35Å to 1.38Å at the transition state. On the other hand, it can be observed that the middle C-C single bond of butadiene has a decreased bond length from 1.45Å to 1.40Å and this implies a strengthening of the bond at the transition state. This is as expected because the Diels-Alder reaction is forming a new C=C bond from this C-C bond of the cis-butadiene molecule. Apart from the bond lengths, the dihedral angles of the two reactants were also shown to have changed significantly- the H-C-C-H dihedral angle of ethylene has decreased from 180o to 154.5o and this is as expected because the the hydrogens are bending away from the plane of the molecule due to steric repulsions from the incoming cis-butadiene reactant. Similarly, the H-C=C-H dihedral angle of the two vinyl groups on cis-butadiene has also decreased from 180o to 155.6o to accommodate the incoming ethylene group.

The successful optimisation of the transition state is also evident from its imaginary vibrational frequency of -956cm-1, which is shown below (Figure 16a). It can be seen from the vibrations that the terminal carbons of ethylene and cis-butadiene reactant are bending towards one another in a concerted fashion during the bond-forming process. On the other hand, when we look at the first positive vibration of 147cm-1 exhibited by the transition state (Figure 16b), it was observed that the bond-forming process takes on a very different mechanism, with one C-C bond being formed first before the next C-C bond was formed in a step-like twisting manner. As the Diels-Alder is a pericyclic reaction, it is evident that the first positive vibration is not a good representation of the transition state (Given no prior knowledge (prejudice?), there is no overwhelming reason for this to be evident. You actually produced some good evidence that the mechanism is synchronous. João (talk) 11:39, 21 April 2015 (BST)). Rather, the vibration with the imaginary vibrational frequency is a better representation (Within the approximations of your calculation, it IS the reaction coordinate at the transition state. João (talk) 11:39, 21 April 2015 (BST)) of the transition state as it shows that the bond forming process follows a concerted type of mechanism.

b)

b)

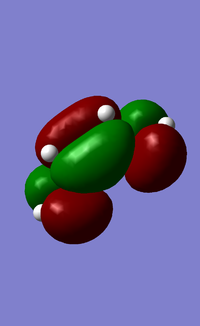

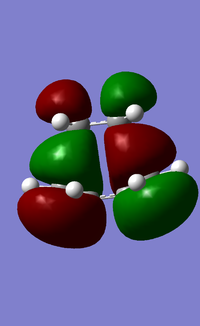

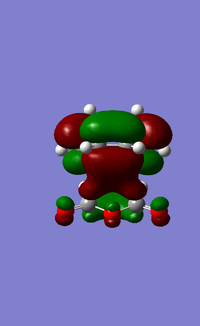

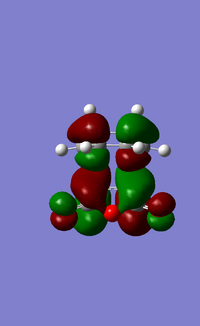

In addition to studying the bond lengths, bond angles and the vibrational frequencies of the transition state, the symmetry of the HOMO and LUMO of the transition state was also obtained and analysed (Figure 17). It was observed that the HOMO of the transition state is anti-symmetrical about the symmetry plane and it consists of the HOMO of cis-butadiene and LUMO of ethylene, both of which are anti-symmetrical about the symmetry plane. The LUMO of the transition state on the other hand, is symmetrical about the symmetry plane and consists of the symmetrical LUMO of cis-butadiene and HOMO of ethylene. Evidently, a favorable overlap was achieved as the respective symmetries of the HOMO/LUMO pairs are matching, and this indicates that the reaction is favorable to proceed. The Diels-Alder reaction discussed here has a "normal electron demand" as the cis-butadiene is electron-rich, and donates its electrons to the LUMO of the electron-poor ethylene dienophile. This is evident from how the HOMO of the transition state is composed of the HOMO of cis-butadiene and LUMO of ethylene. Conversely, an "inverse electron demand" is also possible and it occurs when there are electron-withdrawing groups present on the diene (making the diene electron-poor), and electron-donating groups on the dienophile (making the dienophile electron-rich).

b)

b)

Effect of substituents on the regioselectivity of Diels-Alder reaction

In this last section of the computational experiment, we are looking to study the effect of substituents on the regioselectivity of the Diels-Alder reaction. For this purpose, cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride were chosen to be the diene and dienophile respectively. It is well known that the Diels-Alder reaction between cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride produces two isomeric products, namely the exo and the endo products (Figure 18).

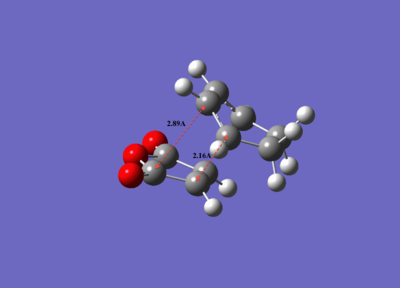

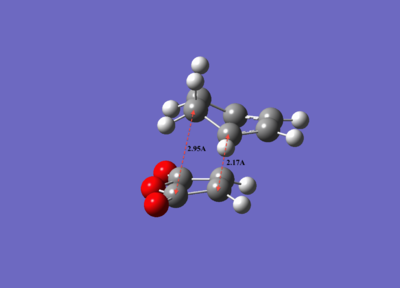

It is a relatively well-established theory that the endo product is the kinetic product of the above Diels-Alder reaction, and is formed more quickly relative to the exo product because of its lower stability (What do you mean by lower stability in this case? João (talk) 11:39, 21 April 2015 (BST)).[9] In this exercise, we will be attempting to prove this by analysing the transition states of the reaction using computational methods. Similar to the previous example where we look at the Diels-Alder reaction between cis-butadiene and ethylene, the geometries and structures of cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride were first optimised using the semi-empirical AM1 method. Subsequently, a guess structure was drawn using the optimised structures and the frozen coordinates method was used as before- freezing the coordinates of the carbon atoms that are involved in the formation of the new bonds in the Diels-Alder reaction to 2.20Å. The results of the optimisation are shown below (Table 5).

| Electronic energy/ a.u. | Dipole moment/D | Symmetry Point group | C-C distance of new bonds formed/Å | Through-space distance of non-reacting carbons/Å | Imaginary vibrational frequency/cm-1 | |

| Endo transition state | -0.05150475 | 6.1670 | Cs | 2.16251 | 2.89209 | -806.39 |

| Exo transition state | -0.05041981 | 5.5641 | Cs | 2.17041 | 2.94527 | -812.21 |

From the results, it was observed that the endo transition state is of a relatively lower (less positive) energy than the exo transition state. This is in good agreement with theory as being the kinetic product of the Diels-Alder reaction, we would expect the Endo product to have a transition state that is lower in energy, as this implies that a lower activation energy is needed for the reactants to reach this transition state and the endo product is thus formed more quickly. The presence of imaginary vibrational frequencies of -806.30cm-1 and -812.21cm-1 for the endo and exo optimised structures respectively, prove that a transition state structure has indeed been achieved. These vibrations are illustrated below (Figure 19).

b)

b)

It was also observed that the C-C bond distances between the two reactants are shorter in the endo transition state than the exo transition state, and this is better illustrated below (Figure 20). While the shorter C-C bond distances between the two reactants of the 'endo' transition state provide a good indication that there is less repulsive (more favourable) interactions between the two reactants, it does not explain why the endo transition is more stable than the exo transition state. A better approach to understanding why this is the case will be to look at the molecular orbitals of the endo and exo transition states.

b)

b)

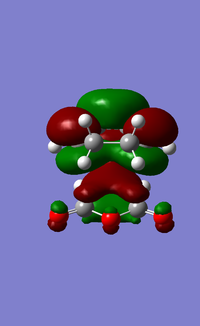

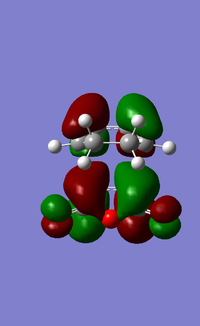

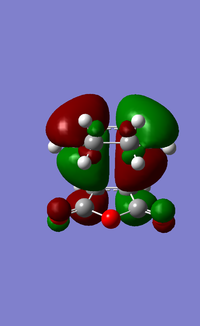

The LUMO+1, LUMO and HOMO orbitals of the endo and exo transition states are shown below (Table 6). A quick comparison between the LUMO+1 orbitals of the two transition states show the presence of a large orbital overlap (middle red orbital) between the cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride reactants in the 'endo' transition state, but not in the exo transition state. This orbital overlap is often termed as a secondary orbital effect, and it corresponds to the stabilising orbital interaction between the π and π* orbitals of the diene and dienophile (Given that you observe this effect in the LUMO+1, would this contribute to the electronic energy of the transition state? João (talk) 11:39, 21 April 2015 (BST)). This stabilising secondary orbital effect is the main contributing factor to the increased stability exhibited by the endo transition state relative to the exo transition state. Interestingly, this secondary orbital effect is however not observed for either the LUMO and HOMO orbitals of the two transition states, as evident from the absence of orbital overlap as shown (Table 6). It is however likely that orbitals below the HOMO in energy level would exhibit this stabilising orbital effect, and would be more pronounced in the endo transition state than the exo transition state. This was however not explored in this study due to time constraints.

| LUMO+1 | LUMO | HOMO | |

| Endo transition state |

|

|

|

| Exo transition state |

|

|

|

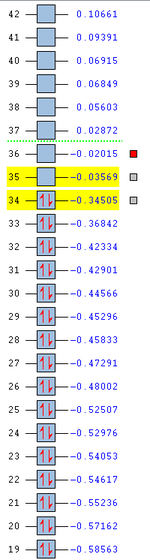

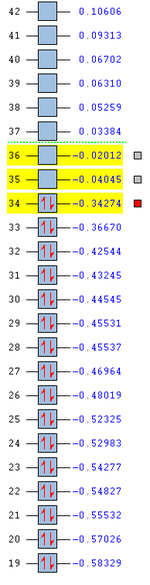

In addition to looking at the extent of the secondary orbital overlap between the two transition states, it can also be observed that the orbital energies of the endo transition state is generally of a lower energy than that of the exo transition state as shown below (Figure 21). Hence, this provides further indication that the endo transition state is more stable than the exo transition state. Evidently, the secondary orbital overlap effect is more pronounced in the endo transition state than the exo transition state (as shown from their LUMO+1 orbitals), and this is key to explaining the relative energies of the two transition states. Consequently, this also provides an explanation to why the endo product is the kinetic product of the Diels-Alder reaction.

b)

b)

Conclusion

Two pericyclic reactions, namely the Cope rearrangement and the Diels-Alder cycloaddition reaction, have been successfully studied using Gaussview in this computational experiment. The study of these reactions was done mainly via analysis of the transition states involved. In the study of the Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene, a total of ten energetically distinct conformer was obtained and the most stable conformer was determined to be the gauche-3 conformer. This was attributed to the stabilising stereoelectronic interactions between the π-molecular orbital of one vinyl group with the C-H orbital of the opposite vinyl group, found only in the gauche-3 conformer. The Chair and Boat transition states of the Cope rearrangement were also studied, and it was found that the activation energy required to reach the Chair transition state was significantly lower by approximately 7-8kcalmol-1 than the Boat transition state, and it was thus concluded that the Chair transition state was more favorable. In the study of the Diels-Alder cycloaddition reaction between cis-butadiene and ethylene, it was shown that the pericyclic reaction does indeed follow a concerted mechanism. In addition, it was observed that the successful overlap of molecular orbitals between the two reactants is key for the success of the reaction. Lastly, the regioselectively of the Diels-Alder reaction was studied using cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride. It was shown that secondary orbital effects play an important role in determining the product of the reaction. A more pronounced stabilising orbital interactions between the reactants of the endo transition state relative to the exo transition state was observed, and this explains why the endo product is the kinetic product of the Diels-Alder reaction.

Future Work

Due to time constraints, it was not possible to look at the other molecular orbitals below HOMO of the endo and exo transition states of the Diels-Alder reaction between cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride. Hence, it might be of value to compare the extent of orbital overlap exhibited by these molecular orbitals of the two transition states, to determine if the secondary orbital stabilising interactions are indeed more pronounced in the 'endo' transition state as shown previously in the LUMO+1 orbitals. Efforts to improve the accuracy of the results could also be done by doing the calculations for the Diels-Alder reaction using the higher B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory (DFT method) rather than the semi-empirical AM1 method. While attempts were made to run the calculations using the DFT method in this study, it was found that each calculation took approximately an hour and was the study was thus not completed due to time constraints.

References

1. H. Mustroph, S. Ernst, B. Senns and A. D. Towns, Color. Technol., 2015, 131, 9–26.

2. R. C. Alkire, T. H. Dunning JR and P. S. Anderson, Natl. Acad. Sci., 1999, 236.

3. K. B. Lipkowitz, T. R. Cundari and D. B. Boyd, Rev. Comput. Chem., 2007, 23.

4. Levine, Ira N., Quantum Chemistry, 1991, pp. 455–544.

5. A. C. Cope and E. M. Hardy, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1940, 62, 441.

6. B. W. Gung, Z. Zhu and R. A. Fouch, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1995, 117, 1783–1788.

7. B. G. Rocque, J. M. Gonzales and H. F. Schaefer, Mol. Phys., 2002, 100, 441–446.

8. Y.-L. Liu and T.-W. Chuo, Polym. Chem., 2013, 4, 2194.

9. Soumendranath, B., Organic Chemistry: An Indian Journal, 2011, 7, 17-20