Rep:Mod:otr12mgo

MgO- Modelling the thermal expansion of MgO using quasi and molecular dynamic methods

Abstract

In this experiment, MgO was analysed using two methods- Lattice Dynamics and Molecular Dynamics. The dispersion relation, the density of states, the free energies and thermal expansion coefficients were calculated and reported. The coefficients of thermal expansion for lattice dynamics compared better to literature than those calculated for molecular dynamics and this was explained by analysing and comparing the models used by Molecular Dynamics to those used for Lattice Dynamics. It was concluded that lattice dynamics is the more accurate for lower temperatures, taking into consideration quantum effects, however, molecular dynamics was more accurate at higher temperatures.

Introduction

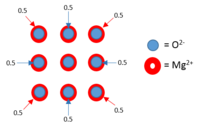

MgO, an ionic lattice consisting of Mg2+ and O2- ions, is a face centered cubic lattice. The cubic form of MgO is known as Periclase, and is present in lower mantle. Calculations on periclase, under conditions imposed in the lower mantle, are difficult to reproduce in laboratory and therefore computation is required. Periclase has been studied vastly throughout literature using the methods used in this experiment.

This experiment made use of two models, lattice dynamics based upon the quasi harmonic approximation and molecular dynamics, allowing for anharmonicity. The quasi harmonic approximation assumes the harmonic approximation for every volume but phonon frequencies become temperature dependent. Molecular dynamics uses Newton's laws of motion to simulate the average parameters of a crystal. Molecular dynamics allows for anharmonicity and thus phonon-phonon interactions which become important at high temperatures. In this experiment both lattice dynamics and molecular dynamics were used to determine the thermal expansion coefficients for MgO and the accuracy of these methods compared. The dispersion relation and density of states for MgO were calculated using lattice dynamics in order to optimise the Monkhorst-Pack grid size.

In this experiment, both the conventional cell and the primitive cell were used to model the MgO lattice. The conventional cell contains 8 atoms and the primitive cell contains 2. The conventional cell used for molecular dynamics was a 2x2x2 supercell consisting of 64 atoms. The primitive cell is based upon a simple rhombodedron and the conventional supercell, a cube.

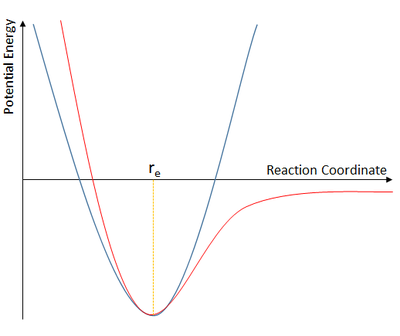

The general utility lattice program or GULP, was originally built to calculate lattice energy using Madelung's constant, but now includes the Buckingham Potential [1], a short-range repulsive interaction between ions. The Buckingham potential incorporates both a Van Der Waals interaction with a r-6 dependence and a Lennard Jones short-range interaction as shown in equation 1 Equation 1: The Buckingham Potential

Where A, and C are adjustable parameters, is the potential and r is the interatomic distance. The Buckingham potential is a simplification of the Lennard-Jones potential. [2]

Both optimisations with respect to Gibbs Free Energies and Helmholtz Free Energies were undertaken in computations and it is important to note the difference. Helmholtz free energy is calculated under constant volume and variable pressure whilst Gibbs Free Energy is calculated under constant pressure and variable volume. When calculating the internal energy of a system at constant temperature and thus constant volume, Helmholtz Free Energy is used. When calculating volumes at different temperatures during thermal expansion, the volume is changing and the pressure is assumed constant and therefore Gibbs Free Energy is used.

Results and Discussion

Calculating the internal energy of an MgO crystal

A calculation was undertaken to determine the binding energy for the MgO lattice. Binding energy is the energy required to separate ions to infinity. The binding energy was calculated to be -41.07531759 eV per primitive unit cell.

Calculating the phonon modes of MgO

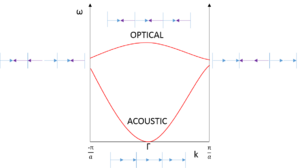

Dispersion relations associate frequency with wave vector, and are graphical representations of all the modes of vibration. Dependent on the character of each vibration, there may be different k values or even different frequencies of the same k value.

Looking at Γ in figure 3, the acoustic and optical branches can be seen as the in-phase and out-of-phase modes of vibration respectively, at the same k value. A band gap arises between these branches and this is dependent on the mass difference between the atoms in the diatomic, for example, no band gap appears for hydrogen. It is also noteworthy that the acoustic branch goes to 0, which corresponds to a pure translation.

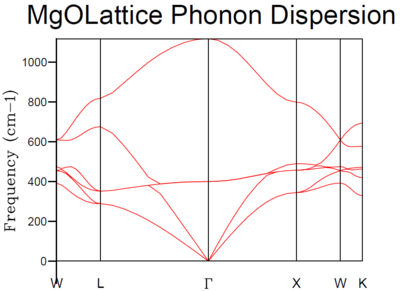

The dispersion relation was computed for 50 points along the k-space coordinate system using GULP.

MgO should exhibit 6 branches with 1 longitudinal and 2 transverse vibrations for both the acoustic and optical branches. This observation is best seen at the W k point, where there are evidently 6 branches. These 6 branches are also depicted in the Density of States. [3] The density of states provides insight into the number of states at each energy level that are available to be occupied by electrons. This was measured whilst varying number of k points used in computation by defining the Monkhorst-Pack grid [4]. The Monkhorst-Pack grid makes use of symmetry within the unit cell to reduce the k points used. A symmetrical k point is repeated within a grid and the unit cells reduced by identifying identical k points and assigning one of these as a k point with twice the contribution. The density of states will be averaged over the grid in reciprocal space. The grid size is defined by a shrinking factor which describes the resolution of the grid.

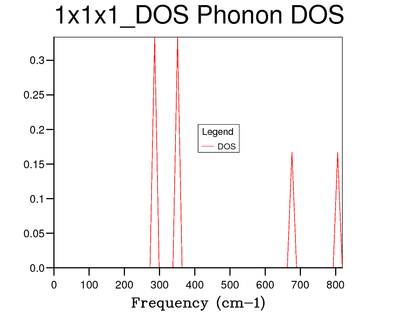

The density of states was calculated initially using a grid of shrinking factor 1 and thus 1x1x1 with 1 k point.

The 4 distinct peaks certainly show no signs of average which is logical taking into regard that the density of states for the 1x1x1 grid was only computed with 1 k point. Comparing the density of states to the dispersion relation, the point on the dispersion relation which corresponds to the point at which the density of states was measured, should exhibit 6 branches, 4 of these will converge on two at frequencies 286 cm-1 and 351 cm-1. This is evident with the 2:2:1:1 intensity ratio between the density of states peaks. The other two branches are accounted for at frequencies 676 cm-1 and 806 cm-1. These attributes are characteristic of the L k point in the dispersion relation and this was confirmed in the calculation output file, with the L k point equal to (0.5, 0.5, 0.5).

The L k point has been chosen by GULP to be the symmetrical point and not Γ, due to an increase in convergence of this point relative to the Γ origin. This has basis in literature [5]

To obtain a better average, the density of states was calculated with shrinking factors of 2, 4, 8 and 16 because doubling the shrinking factor adds successive k points whilst keeping the k points in the original calculation. The density of states for the 16x16x16 grid was shown to be smoother than the 1x1x1 grid and compared well with literature. [6].

The 16x16x16 grid was used for subsequent calculations.

Computing the Free Energy - The quasi harmonic approximation

Lattice dynamics were used to optimise MgO with respect to free energies and differs from the standard harmonic approximation using thermodynamic equilibrium as its reference as opposed to mechanical equilibrium. [7] A calculation was undertaken to determine how the free energy varies with grid size. To further confirm the choice of optimal grid size, the CPU times were also computed.

| Grid Size | Helmholtz Free Energy /eV | CPU time /s |

|---|---|---|

| 1x1x1 | -40.930301 | 0.0038 |

| 2x2x2 | -40.926609 | 0.0052 |

| 4x4x4 | -40.926450 | 0.0170 |

| 8x8x8 | -40.926478 | 0.1284 |

| 16x16x16 | -40.926482 | 1.2617 |

| 32x32x32 | -40.926483 | 23.5560 |

The data reported in table 1 display the convergence of the data on expanding the grid size. It can also be seen that computation time increases dramatically between the shrinking factor of 16 and 32 further confirming the choice of grid size. To explore the accuracy to which each grid size can compute the free energy, the difference between the energy of one grid size and the subsequent grid size was taken.

| ΔF /meV | |

|---|---|

| 1x1x1 | 3.692 |

| 2x2x2 | 0.159 |

| 4x4x4 | 0.028 |

| 8x8x8 | 0.004 |

| 16x16x16 | 0.001 |

For calculations accurate to 0.1 meV and 0.5 meV, it is evident from the |ΔF| values reported in table 2 that the 2x2x2 grid size is appropriate. For accuracy to 0.1 meV per cell the 4x4x4 grid size should be used.

Now the optimal grid size has been found for MgO, the optimal grid sizes for CaO, Li and zeolite will be discussed making comparison to the optimal grid size found for MgO. CaO and MgO share the same face centered cubic structure with the same number of atoms per unit cell. Calcium is a slightly larger atom and so CaO should exhibit a higher inertia and therefore phonons at lower frequency than MgO, confirmed by literature [8]. The density of states in literature shows the optical transverse peak at 10THz or 333.3 cm-1, whereas the equivalent peak in MgO is found at ~12.5THz or 416.7cm-1. It is reasonable to conclude that both these similar face centered cubic structures should share the same grid size.

Lithium is a body centered cubic conductor due to delocalised electrons able to move freely throughout the structure. These delocalised electrons have the effect of dampening vibrations and thus vibrations will be spread out across an energy distribution and a much larger sample of k points is required to analyse an appropriate number of vibrations. Thus, for lithium, a much larger grid size is required to obtain a good approximation of the density of states.

Zeolite is a very large cubic system that is used as a molecular seive. By way of its size, in real space, the unit cell will inevitably be very large. However, the nature of reciprocal space is such that doubling the size of an item in real space, halves its size in reciprocal space and thus zeolite is very small in reciprocal space. Zeolite requires a very small grid size and thus will have a much smaller grid size in reciprocal space than MgO.

The Thermal Expansion of MgO- Lattice Dynamics

| T /K | Free Energy /eV |

|---|---|

| 0 | -40.9019 |

| 100 | -40.9024 |

| 200 | -40.9094 |

| 300 | -40.9281 |

| 400 | -40.9586 |

| 500 | -40.9994 |

| 600 | -41.0493 |

| 700 | -41.1071 |

| 800 | -41.1719 |

| 900 | -41.2430 |

| 1000 | -41.3198 |

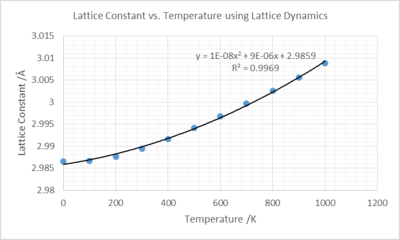

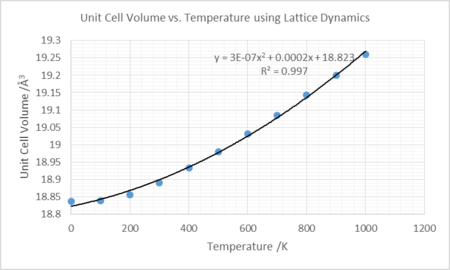

Thermal expansion was investigated by optimising structures on increasing temperature with respect to Gibbs Free Energy, i.e. constant pressure, and the lattice constants and free energies were noted. These were plotted against temperature and reported.

The plot of free energy against temperature shows an increasingly negative free energy for greater temperatures. The plot of free energy with temperature actually provides insight into the entropy of the system using equation 2.

Equation 2: Relationship between Gibbs free energy and temperature

S is the entropy, G is the Gibbs free energy, T is the absolute temperature and P is the pressure. As the gradient becomes more negative with increasing temperature, the entropy increases. This is to be expected as the temperature is increased, vibrations increase in frequency, the structure will inevitably become more disordered and the entropy should increase.

| T /K | Lattice Constant /Å | Unit Cell Volume /Å3 |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2.9866 | 18.8365 |

| 100 | 2.9867 | 18.8383 |

| 200 | 2.9876 | 18.8562 |

| 300 | 2.9894 | 18.8900 |

| 400 | 2.9916 | 18.9325 |

| 500 | 2.9941 | 18.9801 |

| 600 | 2.9968 | 19.0312 |

| 700 | 2.9996 | 19.0851 |

| 800 | 3.0026 | 19.1432 |

| 900 | 3.0056 | 19.1996 |

| 1000 | 3.0088 | 19.2600 |

The plot of lattice constant against temperature displays the tendency of the unit cell to increase on increasing temperature. The physical origin of this thermal expansion lies with the increasing vibrational amplitude leading to a growing interatomic distance and thus an enlarging unit cell. An observed difference between the quasi harmonic and the harmonic potentials is thermal expansion can occur for quasi harmonic because it is unsymmetrical with respect to the average interatomic distance, hence on increasing temperature, this average distance can move. The average distance for a symmetrical potential will remain at the same interatomic distance and thus thermal expansion cannot occur for a system modeled with the harmonic approximation.

One of the key assumptions of the quasi harmonic approximation is there are no phonon-phonon interactions with a weak anharmonic contribution and infinite phonon lifetimes. This is a good assumption at low temperatures. The introduction of anharmonicity also reveals phonon-phonon interactions and the ability of a phonon to decay into another after a finite time. At higher temperatures, where anharmonicity and phonon-phonon interactions become more prevalent, the quasi harmonic approximation becomes less valid and produces spurious results. At the melting point, stated in literature to be 3068K [9], the quasi harmonic approximation is not reliable and thus the phonon modes will not be representative of the motion of the ions.

The thermal coefficient is a measure of the rate of expansion on heating and is defined by equation 2. As a solid is heated, the ions vibrate with greater frequency and the structure begins to fall apart. At high temperatures, small changes in temperature will exhibit larger changes in the structural destruction due to the larger surface area revealed.

Equation 3: The thermal coefficient

For a constant change in temperature and with the initial volume constant, increasing in magnitude reflects the increase in the change in volume with a set temperature increase. An investigation into by how much the volume increases for a constant temperature increase will be undertaken.

The thermal coefficient for MgO was measured in two ways. Firstly, lattice volume was plotted against temperature and a second order polynomial fitted. The fit was differentiated and values for (∂V/∂T) calculated at varying temperatures. This was used to calculate the thermal coefficients.

| T /K | α /K-1 | α Literature /K-1 [10] |

|---|---|---|

| 100 | 1.38030E-5 | - |

| 200 | 1.69883E-5 | - |

| 300 | 2.01736E-5 | 3.12E-5 |

| 400 | 2.33589E-5 | 3.39E-5 |

| 500 | 2.65442E-5 | 3.57E-5 |

| 600 | 2.97295E-5 | 3.72E-5 |

| 700 | 3.29148E-5 | 3.84E-5 |

| 800 | 3.61001E-5 | 3.93E-5 |

| 900 | 3.92854E-5 | 4.02E-5 |

| 1000 | 4.24707E-5 | 4.08E-5 |

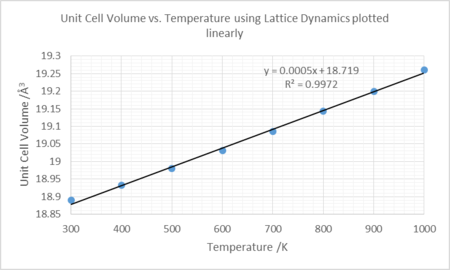

The thermal coefficient for the linear plot was found by disregarding the points up to but not including 300K on the plot of volume against temperature, and finding the line of best fit. The gradient was used to calculate the thermal coefficient. This was found to be 2.65443E-5 K-1 and assumes the thermal expansion coefficient is independent of temperature.

The data compare well with literature at temperatures ~1000K with greater deviations ~300K. The linear plot does not fit as well as the data produced by the second order polynomial, however, is similar in magnitude and thus the approximation, at these temperatures, is not inaccurate.

Interestingly, the literature obtained disagrees with literature found for the thermal expansion coefficient at 273K. This was stated in other literature [11] to be 1.08E-5 K-1 and using the second order polynomial, the thermal expansion coefficient at 273K was calculated to be 1.9312E-5 K-1. The data computed and the literature, in the case of 273K, is a better comparison than the literature reported in table 5.

The graph shown in figure 11, displays a linear dependence of the coefficient of thermal expansion and temperature. This can be evaluated mathematically by equating the linear dependence of , with equation 2, and solving the separable differential equation.

Equation 4: The non-linear dependence of the change in volume with temperature

The second order dependence of the change in volume with temperature displays that the volume will change more as temperature is gradually increased.

The Thermal Expansion of MgO- Molecular Dynamics

Molecular dynamics was now be used to simulate the thermal expansion of MgO and these methods compared. The primitive cell will no longer be used, but a conventional supercell with 64 atoms to sample more phonons.

An NPT ensemble was chosen, with constant number of particles, pressure and temperature, in order for volume to vary. Temperature was initially set to 100K with a timestep 1.0fs, equilibration and production steps set to 500 and sampling and trajectory steps set to 5.

| T /K | Supercell Volume /Å3 | Volume per formula unit /Å3 |

|---|---|---|

| 100 | 599.5524 | 18.7772 |

| 200 | 600.8710 | 18.7772 |

| 300 | 602.9166 | 18.8411 |

| 400 | 604.1889 | 18.8809 |

| 500 | 606.0024 | 18.9376 |

| 600 | 608.3782 | 19.0118 |

| 700 | 610.2642 | 19.0708 |

| 800 | 611.9543 | 19.1236 |

| 900 | 613.7457 | 19.1800 |

| 1000 | 615.6256 | 19.2383 |

| 1100 | 616.2115 | 19.2566 |

| 1200 | 618.1414 | 19.3170 |

| 1300 | 619.5876 | 19.3621 |

| 1400 | 621.3700 | 19.4178 |

| 1500 | 623.2816 | 19.4776 |

| 1600 | 626.1598 | 19.5675 |

| 1700 | 628.0537 | 19.5675 |

| 1800 | 629.7587 | 19.6800 |

| 1900 | 631.2004 | 19.7250 |

| 2000 | 634.8047 | 19.8376 |

| 2100 | 637.4430 | 19.9201 |

| 2200 | 639.1740 | 19.9742 |

| 2300 | 641.2636 | 20.0395 |

| 2400 | 642.7851 | 20.0870 |

| 2500 | 649.8834 | 20.3089 |

| 2600 | 647.6905 | 20.2403 |

| 2700 | 652.2408 | 20.3825 |

| 2800 | 652.6556 | 20.3767 |

| 2900 | 654.5936 | 20.4560 |

| 3000 | 660.4274 | 20.6384 |

The values reported in table 4 were plotted alongside those provided by lattice dynamics and the graphs compared. It can be seen at low temperatures (~100K), the models don't compare. The reason for this lies with the presence of quantum effects at low temperatures that molecular dynamics neglects. The models compare well up to 1100K when they deviate. It is also to be expected that heating the material should render the material easier to heat on subsequent heating and therefore an increasing gradient of volume with temperature should be seen as smaller temperature increases should yield larger volume differences. Molecular dynamics disregards the melting point of the structure whilst lattice dynamics, as was evident in visualisation, displays a vastly deformed structure at the melting point. The thermal expansion coefficients calculated with molecular dynamics were reported and analysed to compare with lattice dynamics.

| T /K | α /K-1 | α Literature /K-1 |

|---|---|---|

| 100 | 2.19897E-05 | - |

| 200 | 2.26302E-05 | - |

| 300 | 2.32707E-05 | 3.12E-5 |

| 400 | 2.39112E-05 | 3.57E-5 |

| 500 | 2.45517E-05 | 3.84E-5 |

| 600 | 2.51921E-05 | 4.02E-5 |

| 700 | 2.58326E-05 | 4.14E-5 |

| 800 | 2.64731E-05 | 4.26E-5 |

| 900 | 2.71136E-05 | 4.38E-5 |

| 1000 | 2.7754E-05 | 4.47E-5 |

| 1100 | 2.83945E-05 | 4.56E-5 |

| 1200 | 2.9035E-05 | 4.65E-5 |

| 1300 | 2.96755E-05 | 4.71E-5 |

| 1400 | 3.0316E-05 | 4.80E-5 |

| 1500 | 3.09564E-05 | 4.89E-5 |

| 1600 | 3.15969E-05 | 4.98E-5 |

| 1700 | 3.22374E-05 | 5.04E-5 |

| 1800 | 3.28779E-05 | 5.13E-5 |

| 1900 | 3.35183E-05 | 5.22E-5 |

| 2000 | 3.41588E-05 | 5.33E-5 |

Comparing the thermal expansion coefficients calculated with molecular dynamics with literature, it can be seen that initially the thermal expansion coefficients are a better comparison to the literature than lattice dynamics. However, there are great differences between the values and growing differences at higher temperatures. Molecular dynamics seems to be underestimating the thermal expansion and this is a known problem in literature. [12]. However, as discussed with lattice dynamics, the disagreement of literature provides an unreliability in comparing data to one literature set. The thermal expansion coefficient calculated at 273K was found to be 2.3100E-5 K-1. Comparing to the literature found at 273K (1.08E-5 K-1), it can be concluded that the thermal expansion coefficient for molecular dynamics is a worse fit than lattice dynamics according to this literature. This is to be expected and so the data tend to agree more with the literature found at 273K.

The graph of unit cell volume vs temperature for molecular dynamics shows evidence that each calculation made is independent of other calculations, due to the random initial velocities, leading to deviations in the trend. Every time a new molecular dynamic calculation is run, new velocities are calculated and thus new positions predicted. However, the velocities used in calculation are random and thus will not produce consistent results. The graph also reveals that at high temperature, the volume of the unit cell rises at a quicker rate than the cell volume at the same temperature range, predicted by molecular dynamics.

As has been discussed previously, lattice dynamics relies on the quasi harmonic approximation, neglecting phonon-phonon interactions and with very little to no anharmonic contributions whilst molecular dynamics takes into consideration these anharmonic effects and thus phonon-phonon interactions. The methods produce different outputs due to their vastly differing assumptions. At low temperatures, lattice dynamics should be used for the most accurate model, however, at higher temperatures, molecular dynamics.

The molecular dynamics performed in this experiment has made use of the conventional supercell consisting of 8 unit cells. The results obtained have been a good approximation and fit well with literature found and expectations. For more reliable results the 4x4x4 supercell could be used, sampling more phonon modes and obtaining better averages. Furthermore, the production/equilibration steps could be set to 5000 to ensure better convergence. These changes would be time costly, but would produce more reliable and accurate results.

Conclusion

Lattice dynamics was used to calculate the internal energy, the dispersion relation and the density of states at varying grid sizes to determine the optimal grid size. It was found that the 16x16x16 grid was the most accurate compromising with CPU time. It was shown using the 1x1x1 grid, that the origin chosen by GULP was not Γ but the L k-point and this was identified to be better for convergence. The density of states and the dispersion relation were compared and a relationship was found between them. The 16x16x16 grid was used on subsequent calculations for the thermal expansion of MgO with both lattice dynamics and molecular dynamics.

Lattice dynamics was used to optimise the structures with respect to the Gibbs Free Energy and volumes plotted with respect to temperature. The thermal expansion coefficients were initially calculated by fitting a second order polynomial and calculating the gradients at different temperatures. Subsequently, the points up to and not including 300K were neglected in order to approximate the data to a linear trend. The gradient was used to calculate a coefficient of thermal expansion independent of temperature. The coefficients of thermal expansion compared well with literature, but it differences in literature were discussed.

Molecular Dynamics were then used to compute the volume as a function of temperature. The coefficients of thermal expansion were calculated using the second order polynomial method and were compared to literature. The coefficients of thermal expansion compared well, in general, to literature, however, underestimated the thermal expansion according to one literature set. However, comparing the coefficients of thermal expansion to literature measured at 273K, the expectation that molecular dynamics should be a worse model at low temperatures agrees with observation. It was concluded that the literature measured at 273K may be more reliable.

Lattice dynamics, using the quasi harmonic approximation, is a better treatment for computations at a lower temperature, taking into regard quantum effects but neglecting the anharmonic approximation, which at these temperatures does not have a significant contribution to the potential. Molecular dynamics, using Newtonian mechanics and random velocities, neglects the quantum effects at low temperatures but assumes anharmonicity and allows accurate calculation at higher temperatures.

References

<references> Template loop detected: Template:Reflist

- ↑ J.D Gale, A.L Rohl, The General Utility Lattice Program (GULP), Molecular Simulation, 29:5, pp291-341

- ↑ R. A. Buckingham, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences 168, 1938, pp. 264-283

- ↑ V.A. Henrich, P.A. Cox, The Surface Science of Metal Oxides, pp 79

- ↑ H.J Monkhorst, J.D. Pack Phys. Rev. B,13, 1976, 5188

- ↑ J. Moreno, J.M. Soler, Phys. Rev. B, 45, 1992, pp. 13891

- ↑ B. D. Bartolo, O, Forte, Frontiers Developments in Optics and Spectroscopy, 7-17

- ↑ R. G. Della Valle, E. Venuti, Phys. Rev. B1, 58 , 1998, pp 206-212

- ↑ H. Bilz, W. Kress, Phonon Dispersion Relations in Insulators, pp 51

- ↑ L.S. Dubovinsky, S.K. Saxena, Phys Chem Minerals , 24, 1997, pp 547 - 550

- ↑ O.L. Anderson, K. Zou, J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data , 19, 1990

- ↑ Crystan, Accessed 17/1/14

- ↑ Y. Mitrokhin, V.P. Belash, N.N. Stepanova, V.Shudegov, Journal of Physics: Conference Series , 98, 2008