Rep:Mod:osef-module2

BH3

BH3 - Structure Optimisation

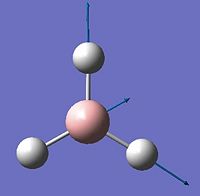

A .com file containing a BH3 molecule was made in Gaussview. The bond lengths were set to be 1.5 Å, and the structure of the BH3 molecule was then optimised in Gaussian using a b3lyp/3-21g basis set. The calculation successfully converged, giving the structure as trigonal planar, with H-B-H angles of 120.0 degrees and B-H bond lengths of 1.19 Å. The dipole moment is calculated to be 0. This is expected, because from the symmetry of the molecule, we expect the polarity of the bonds to cancel out.

The Total Energy graph, as its name suggests, illustrates the the energy of the molecule as the optimisation proceeds. The operation stops when the gradient of the Energy vs. bond length curve reaches zero. The energy vs bond length curve is also known as a potential energy surface or PES for short. This surface shows how the potential energy of the molecule varies with bond lengths. Most molecules have more than one bond, so their PES must be shown in several dimensions. Clearly when more than two bonds are present, one needs to invoke a grouping of the bond lengths as a "reaction coordinate". It is this reaction coordinate that is varied in the case of the optimisation of the BH3 structure. At each step, gaussian modifies the reaction coordinate and 'sees' how the energy varies. When the energy varies very little with a small change in reaction coordinate (RMS Gradient), the iterations are stopped, and the energy of the molecule is stopped. In this case, the energy of BH3 is calculated as -26.46 Hartrees or -69.47 kJ/mol.[1]

BH3 - Molecular Orbitals and NBO

The molecular orbitals (MOs) and the natural bond (NBO) order calculations were performed on the optimised structure of BH3 using a DFT/B3LYP method.[2] The resulting molecular orbitals and their LCAO analogues are shown below.

MOs vs. LCAO

| MO number (symmetry) | Energy |

Calculated MO | LCAO MO |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (1a1') | -6.730 |  |

|

| 2 (2a1') | -0.517 |  |

|

| 3 (1e', HOMO) | -0.356 |  |

|

| 4 (1e', HOMO) | -0.356 |  |

|

| 5 (1a2, LUMO) | -0.074 |  |

|

| 6 (2e') | 0.188 |  |

|

| 7 (2e') | 0.188 |  |

|

| 8 (3a1') | 0.191 |  |

|

As a general comment, the LCAO based MOs are relatively close to the calculated MOs. The latter seem to be smoother, and overlap between same-phase densities is seemless. Similarly, opposite-phase interactions are more pronounced, and distort the orbitals a little more, making it slightly more difficult to match these with their LCAO counterparts. Nevertheless, in the case of BH3, the LCAO provides a very good indication as to the shape of the orbitals. It also provides some valuable information on the reactivity of the molecule in question. In this case, It provides us with the fact that an empty p-orbital is the LUMO, making nucleophilic attack onto such a low lying empty orbital quite facile. Indeed, the difficulty of isolating BH3 free of coordinating solvents or free of dimerisation clearly vouches for this statement.REFERENCE This is also confirmed by the MO calculations, in which the LUMO has a negative energy.

NBO analysis

Opening of the .log file in Gaussview allows us to rapidly assess the NBO charge on the atoms in the molecule either as colours (green is positively charged, and red is negatively charged), or as text, as shown below. The negative charge on the hydrogens clearly illustrate the hydridic nature of these atoms in BH3.

| Colours | Text/Numbers |

|---|---|

|

|

Closer inspection of the .log file allows us to discover the hybridisation of the atoms involved in bonding, the particular distribution of electrons (core, valence etc.), as well as how they are distributed among the orbitals. In the case of BH3, the NBO summary tells us that the first 4 orbitals are doubly occupied, and have a negative energy. The next orbital with the lowest energy is the LUMO and in this case is molecular unit 8, with a negative energy. A look at the NBO analysis tells us that molecular unit 8 is unhybridised, and exists solely as a p-orbital. The deepest lying occupied orbital is purely localised on the boron, and has 100% s-character. This is therefore the core 1s orbital from the boron atom. The remaining three occupied orbitals are all involved in B-H bonding, and are composed of 44.48% of an sp3 hybridized orbital (from the boron atom) and 55.52% of an unhybridised s-orbital (from the hydrogen atoms). This leads to the conclusion that the molecule is entirely symmetrical, and that all the B-H bonds are equivalent.

BH3 - Vibrations

Using a RB3LYP model, the frequencies of the optimised BH3 molecule were computed, and are shown in the table below.[3] The spectrum of BH3 shows only 3 peaks, as opposed to the 6 vibrations that were computed and predicted from the 3N-6 rule. This is due to the fact that vibration 4 is totally symmetric and incurs no change in dipole moment, hence is not observed in IR spectroscopy, as shown by the computed intensity of 0. Vibrations 2 and 3 are degenerate, so will overlap on the spectrum, leading to a single peak of double the predicted intensity (12). This is indeed observed. Similarly, vibrations 5 and 6 are degenerate, and manifest themselves as a single peak of double the predicted intensity.

BCl3

BCl3 - Optimisation

A molecule of BCl3 was drawn in Gaussian and restricted to a D3h symmetry. The structure was then optimised using a B3LYP/LANL2MB basis set from a DFT method.[4] This particular medium level basis set is used because it uses pseudo potentials for atoms beyond the first row (Cl in this case). The resulting structure exhibits a trigonal planar boron center, with a B-Cl bond length of 1.87 Å and a bond angle of 120 degrees, compared to the literature value of 1.74 Å and 120 degrees.[5] The energy of the optimised structure is -69.44 hartrees, or -182.31 kJ/mol.

BCl3 - Frequency Analysis

In order to verify if the energy and hence the structure optimised is a maxima or a minima (since optimisation only provides a point of gradient 0 on a PES), we must perform a frequency analysis. At a minimum on a PES, all vibrational frequencies must be positive (i.e. d2y/dx2 = +ve). A vibrational analysis was therefore performed on the optimised structure, with the same basis set as before.

[6] It is necessary to use the same basis set as that of the structure optimisation, so as to compute the vibrations of the ground state, rather than an excited state.[7] The calculation took 12 seconds to complete, and the computed frequencies are shown in the table below. The trigonal planar nature of the molecule leads to the conclusion that the point group of the ground state structure is D3h, which is indeed observed in the .log file of the vibrational analysis. The IR spectrum of BCl3 shows only 3 peaks, as for BH3. The reasons for this are the same: vibration 4 has a center of inversion, so is IR inactive, and vibrations 1 and 2 are degenerate so appear as a single peak with double the expected intensity. This is also true for vibrations 5 and 6.

Chemical bonds can be described as a link between atoms. The underlying rationale behind this simplistic description is that for two atoms to stay together, there must be a favourable interaction between them. Predictions are that two neutral atoms will repel each other due to the electrostatic repulsion of their electronic clouds. However, bonds form when favourable interactions (ones which will compensate for the repulsion) between the atoms are possible. Hence 'sharing' of electrons leads to bonds. This is seen in the BH3 NBO analysis, where 2 electrons are shared nearly equally between a hydrogen and a boron atom. This is a 2 center - 2 electron bond, but other types of bonds are possible. I therefore would define a bond as a sharing of electrons between 2 or more atoms. Gaussview, however, defines bonds according to the distance between the two atoms, which in some cases where 'bonded' atoms are further away than the bond length suggested by Gaussview, leads to the bonds not being draw in.

Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 - cis and trans Isomerism

Optimisation of the Structures

Primary optimisation of the structures was performed using the DFT/B3LYP method and a LanL2MB basis set, with an additional comment being opt=loose, thus enabling loose convergence criteria. This first optimisation converged for both the cis[8] and trans[9] isomers. This particular optimisation with a loose convergence criteria allows us to ensure that the optimised structure reaches a minimum on the PES. However, it does not ensure that the minimum obtained is the one with the lowest energy. In order to reach this lowest minimum, it is imperative to find the appropriate starting point, so as to not 'fall' into the wrong minimum, or potential well. To further refine the optimised structure, the PCl3 groups were orientated in the following way: For the cis isomer, one PCl3 group was orientated such that one Cl points up, and the other PCl3 group was orientated such that one Cl points down. In the trans isomer, the PCl3 groups were eclipsed, with one P-Cl bond being aligned with a Mo-C bond. For clarity, refer to the Jmol files in the table below. After these modifications, the structure was optimised using a DFT/B3LYP method with a more accurate, LanL2DZ basis set, with an increased convergence using the additional comment: int=ultrafine scf=conver=9. The results for the cis[10] and trans[11] isomers are shown in the table below.

Metal-ligand interactions are not always purely σ-type interaction, and depend vastly on the electronics of the ligand. Metal complexes containing CO are generally quite stable, due to the high stability of M-CO bonds. This is especially true for metals in low oxidation states, which can donate electron density into the π*C=O. This backbonding provides additional stabilisation to the M-C bond, in addition to the classical σ-type interaction. IR studies enable chemists to probe the M-C bond and assess the bonding mode (M-CΞO vs. M=C=O). This will be addressed computationally in a later study. Phosphenes also exhibit this type of backbonding. The major difference with the CO ligand is that the lone pair on the phosphorus atom quite basic and is readily involved in σ bonding. Phosphenes also accept electron density, but into empty orbitals located on the P atom, rather than into a π* orbital. PF3 phosphenes have the same π* accepting properties as CO, and since π* accepting capability is inversely proportional to the basicity of the phosphene, we can conclude that PCl3 will be slightly less of a π* acceptor ligand, due to the reduced basicity compared to PF3.[12] The methods of optimisation used previously did not take into account this π* accepting nature of phosphenes, so in order to remedy this, a modification of the calculation was performed. The d-orbitals on the phosphenes (acceptor orbitals) were included in the LanL2DZ basis set by adding an "extrabasis" including the d-orbitals at the bottom of the input file. This was performed for both the cis[13] and trans[14] isomers.

| Cis (LanL2MB) | Cis (LanL2DZ) | Cis (LanL2DZ + extrabasis) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

| |

| Energy (Hartrees) | -617.525 | -623.577 | -623.693 |

| Energy (106 kJ/mol) | -1.621310 | -1.637200 | -1.637510 |

| Trans (LanL2MB) | Trans (LanL2DZ) | Trans (LanL2DZ + extrabasis) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

| |

| Energy (Hartrees) | -617.522 | -623.576 | -623.694 |

| Energy (106 kJ/mol) | -1.621300 | -1.637200 | -1.637510 |

Note: The energies are computed to the nearest 0.004 Hartree (10 kJ/mol)

Now we have computed the respective energies of the isomers with different basis sets, we need to check if these energies are in fact minima or maxima, for reasons previously explained. We therefore calculate the vibrations of each optimised structure (LanL2DZ and LanL2DZ + extrabasis) with the LanL2DZ basis set and the same keywords: int=ultrafine scf=conver=9. The results for the cis[15][16] and trans[17][18] isomers can be found in the references below. We will only analyse a set number of vibrations which can be of interest and are particularly present in the spectrum. The first conclusion that we can draw from the vibrational analysis is that the structure optimised using the extrabasis function did not converge on frequency analysis (force or displacement). This is even further apparent in the vibrations derived from this structure, where some vibrations appear to have negative frequencies (-50). For the purely LanL2DZ-optimised structure, the frequency analysis converged, and it is this structure that we will use to analyse the vibrations. Knowing this allows us to discard the structure optimised using the extrabasis frequency. Consequently we can compare the energies of the cis and trans structures obtained from the LanL2DZ basis set. It is apparent that there is a small difference in energy between the two structures (0.001 Hartrees). This is equivalent to an energy difference of 2.6 kJ/mol, roughly the same as the thermal energy available at room temperature (RT = 2.5 kJ/mol). From this it can be deduced that the two structures could interconvert quite readily at room temperature, provided that the activation barrier for this isomerisation is not too high. This interconversion is in fact confirmed by the literature. [19]. Due to the fact that the difference between the two structrures of interest (2.6 kJ/mol) is less than the error incurred by the calculations used (10 kJ/mol), deciding to the relative stability of the isomers purely on the computational output is not acceptable. Suffice to say that the two structures are very close in energy. Nevertheless, the trans structure may be predicted to be lower in energy for steric reasons and this is in fact confirmed by the literature.[19] To prefer one particular isomer, tweaking the nature of the phosphine can be very helpful. Large, bulky substituents on the phosphorus atoms are more likely to favour the trans geometry for steric reasons. A P(tBu)3 type phosphine would most definately favour the trans isomer, since its Tolman cone angle is increased from 125º in PCl3 to 182º, and considering that the PCl3 ligand has its cis and trans isomers at more or less the same energy, it is not unreasonable to assume that P(tBu)3 ligands would favour the trans isomer.

The trans isomer appears to be highly symmetrical, as predicted from its D4h point group (assuming the phosphine rotates freely about the Mo-P bond). Bond lengths of the Mo-P bonds are very similar, as are the Mo-C bonds, and the bond angles around the metal center do not seem to be distorted (90º for P-M-C angle). The cis isomer does exhibit some distortion in the bond angles around the metal (89º and 91º for P-M-C angles), and this is even clearly apparent from simply looking at the jmol structure. Even the M-C-O angle is distorted from the expected 180º to 177.9º Furthermore, there is a clear difference between M-C bond lengths of equatorial COs and axial ones (2.01 vs 2.06 Å). This may be due to the fact that equatorial COs are trans to π* accepting phosphines, resulting in competition for backdonation. Consequently, there is less backdonation into the CO π*, meaning that the bond is closer to a triple bond, and is thus shorter.

| Mo-C (Å) | Mo-P (Å) | |

|---|---|---|

| LanL2DZ (average) | 2.035 | 2.512 |

| Literature[20] | 2.004 | 2.544 |

| Mo-C (Å) | Mo-P (Å) | |

|---|---|---|

| LanL2DZ (average) | 2.060 | 2.444 |

| Literature[19] | 2.016 | 2.500 |

Compared to the literature, the cis structure is consistently within 0.03 Å, whereas the trans is always within 0.1 Å. The accuracy of the two is not that great, but the literature values are those of triphenyl phosphine ligands rather than trichlorophosphine, so the results are acceptable. Comparing the Ir analysis with the experimental data will confirm (or not) the power of computational methods in predicting the structure.

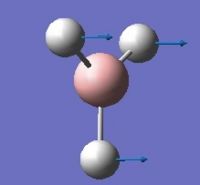

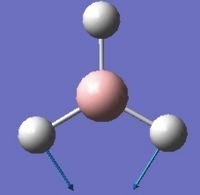

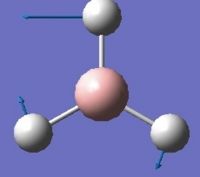

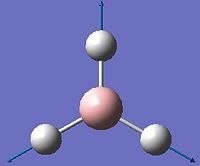

IR Analysis

From the vibrations of the cis and trans isomers, it can be seen that there are a large number of low frequency vibrations which include bending, twisting, rocking. An example of the vibrations found below 40 cm-1 are shown on the models of the isomers. The very low frequencies of these vibrations indicate that at room temperature, the complex is effectively a time-averaged structure resulting from these vibrations. These vibrations only incur a very small change in dipole moment (small enough to make them negligible on IR spectra), mainly due to the fact that they do not involve large changes in bond lengths compared to stretching frequencies. The stretching (and more severe bending) frequencies are generally located at higher wavenumbers, and hence higher energies. For example, the CO stretching frequencies are the highest in energy, due to their higher bond strength and polarity. Therefore, a small asymmetric change in the bond length will result in a relatively large change in dipole moment compared to a slight twisting of the trichlorophosphine groups.

| Cis Spectrum | Trans Spectrum |

|---|---|

|

|

There are four major CO stretches in both the cis and trans isomers. In the cis isomer, all four are active and observed at ca. 1950-2050 cm-1. Conversely, the spectrum of the trans isomer only shows a single peak at 1950 cm-1, resulting from the two degenerate Eu asymmetric stretches. The remaining two stretches are not observed since they are symmetrical, and therefore provide no change in dipole moment. Consequently, these vibrations are IR inactive.

| Stretching Mode | Symmetry | Calculated Frequency (cm-1) | Literature Frequency (cm-1)[21] | Calculated Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

eu | 1950 | 1905 | 1475 |

|

eu | 1951 | 1905 | 1467 |

|

b1g | 1977 | - | 1 |

|

a1g | 2031 | - | 4 |

The CO vibrations that appear first on the spectrum of the trans complex are the degenerate eu pair. These involve the asymmetric stretch of a pair of carbonyl groups which are trans-related. In the calculation, these are not perfectly degenerate because the trichlorophosphine groups are fixed about the P-Mo bond, thus rendering the pair of stretches non-degenerate. However, we can immagine, for reasons previously evoked, that the trichlorophosphine groups rotate quite freely about the P-Mo bond, thus making the pair of CO vibrations identical. This is what is observed experimentally, whereby the two stretching frequencies of the vibrations of interst are joined at 1905 cm-1. However, there is a clear discrepancy between the observed and calculated frequency. The possible reasons for this are mostly summarised by the relative inaccuracy of the computational method used. This method assumes harmonic type oscillations, whereas atoms are known to vibrate in an anharmonic fashion. This drastic simplification leads to a 10% error on the calculated frequencies (ca. 200 cm-1 error in the case of the eu frequencies). This, in addition to the fact that d-orbital contribution of the phosphine groups are not taken into account, leads to the conclusion that the calculation exceeds the expected accuracy. The other two vibrations have an associated center of inversion, and therefore do not lead to a change in dipole, and hence have an extremely low predicted intensity. Experimentally, these stretches are lost to the noise, given the large intensity of the eu peaks.

| Stretching Mode | Symmetry | Calculated Frequency (cm-1) | Literature Frequency (cm-1) [21] | Calculated Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

b2 | 1945 | 1897 | 763 |

|

b1 | 1949 | 1908 | 1498 |

|

a1 | 1958 | 1927 | 632 |

|

a1 | 2023 | 2023 | 598 |

The vibrations of the carbonyls in the cis complex are similar to the ones in the trans isomer, in that two stretching modes mainly involve the only two carbonyls (and a slight stretching of the other two), and the other two modes involve all four carbonyls. In the trans isomer, the vibrations involving all four carbonyls are not observed due to symmetry considerations, namely the center of symmetry. However, in the cis complex, there is no such center of inversion, and consequently all modes are IR active. Predictably, the most intense stretching mode is the b1 stretch, in which we observe an asymmetric stretch of the axial pair of carbonyls. The change in dipole is greatest in this particular vibration because the dipole change of each specific carbonyl is additive. Similarly, the pair of COs stretching in the equatorial positions (b2) also lead to a large change in dipole moment. However, this change is reduced by the fact that the individual change in dipole moments are orthogonal to each other, and cancel out slightly. In the two a1 stretching modes, the overal change in dipole moment is also less than the b1 mode, for similar reasons as the b2 stretch. As in the trans complex, the accuracy of the calculated frequencies is not exceptional, but acceptable, considering the errors/assumptions involved in the calculation.

Mini Project - Investigating the influence of halides on the stability of Grignard reagents and their dimers

Introduction

Numerous studies have been made on the structure of Grignard reagents in the solution phase. These RMgX type molecules tend to aggregate to form dimers, with structures similar to diboranes and trialkylaluminium compounds, containing groups bridging between two magnesium centers in a 3-center-2-electron fashion. The formation of these dimers is best described by the Schlenk equilibrium shown below.[22] The number of different magnesium-based species is further increased if the Grignard is in an etheral solution. Indeed, magnesium has a strong affinity for the lone pairs on the ether oxygen, and will coordinate to them. However, these species can readily transform to either the RMgX or R2Mg and MgX2 species, which in turn are in equilibrium with other aggregates. For this project, we will investigate the effect of the halide on the stability of the dimer, and attempt to shed some light on the bonding, paying particular attention to the bridging groups.

Structure optimisation

An initial structure optimisation using the DFT/B3LYP method and a LanL2MB basis set (opt=loose) was made for the MeMgBr dimers in which the methyl groups are in the terminal positions. There are several possible options, one where the methyl groups are on the same Mg atom, and the other Mg atom coordinates to two ether molecules, another where the the methyl groups are on opposite Mg atoms. The latter structure can exist as cis and trans, but due to time constraints we will only focus on the trans isomer. These two basis structures were used to build the other models, and a more accurate LanL2DZ basis set (int=ultrafine scf=conver=9) was used to further refine them. The table below shows the structures, energies (LanL2DZ), jmol structures, and the link to the digital object identifier for the calculation.

| Anion | Bromide | Iodide | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure |

| |||||||

| Energy (Hartrees) | -575.344[23] | -575.318[24] | -575.348[25] | -575.323[26] | -571.760[27] | -571.741[28] | -571.772[29] | -571.749[30] |

| Energy (106 kJ/mol) | -1.510570 | -1.51050 | -1.510580 | -1.510510 | -1.501160 | -1.501110 | -1.501190 | -1.501130 |

| Jmol | ||||||||

Note: the naming of the compounds is attributed as follows: 1: MeMgBr, 2: MeMgI, t: terminal me, b: bridging, o: terminal groups on opposite Mg centers, s: terminal groups on the same Mg center.

The first observation that can be made from the above data is that the bromide-based Grignard reagent appears to be slightly more stable than its iodide analogue, and this regardless of the isomer. The difference between them is always close to 1000 kJ/mol. The increased stability of the bromine based dimers can probably be attributed to the better orbital overlap with the Mg atoms, compared to the large, diffuse nature of the iodine orbitals.

The structures above were submitted to the SCAN for frequency analysis in order to determine whether they were in fact structures corresponding to the minima of their respective PES curves. The same method and basis set (DFT/B3LYP and LanL2DZ) were used. The output file (.log) indicated that the force items converged, but not the displacement items. A possible reason for this would be due to the large number of low frequency vibrations associated with these structures (over a dozen vibrations with frequencies below 100 cm-1), indicating low force constants of the PES curves (ca. 0.02). As a result, the PES curve is quite wide, and a small change in energy leads to large change in displacement (compared to a corresponding PES with large force constant).

Structure Comparaison

| Mg-X | Mg-X (lit)[31] | Mg-Me | Mg-Me (lit)[31] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1to | 2.713 | 2.656 | 2.098 | 1.990 |

| 1ts | 2.889 | - | 2.115 | - |

| 1bo | 2.510 | 2.464 | 2.246 | 2.194 |

| 1bs | 2.518 | - | 2.361 | - |

| 2to | 2.948 | - | 2.094 | - |

| 2ts | 3.775 | - | 2.113 | - |

| 2bo | 2.720 | - | 2.247 | - |

| 2bs | 2.757 | - | 2.272 | - |

The bond lengths of 1to and 1bo match the literature values to one decimal place, indicating that the structures computed are correct. Since the remainder of the structures were computed from the 1to dimer, it is not unreasonable to assume that the other structures are correct as well. However, the Mg-X bond length of 2ts is much larger than 2to, and if we have a look at the structure, we see that the Me2Mg group lies much closer to one iodine atom than the other (3.172 vs. 6.458 Å), thus strongly affecting the average bondlength. A different starting structure was defined and minimised, only to give the same structure again.[32] This leads to the conclusion that either the computational method used is not appropriate for this structure, or simply that this structure is highly distorted. Unfortunately not literature corresponding to this compound could be found. The Br-Mg-Br bond angle of 1to (89.4º) strongly correlates with the literature value of 89.3º, again suggesting that the structure is correct.[31]

IR/Vibration analysis

| 1to[33] | 1ts[34] | 1bo[35] | 1bs[36] |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| 2to[37] | 2ts[38] | 2bo[39] | 2bs[40] |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

It is immediately apparent that changing the halide affects the shape of the spectrum very little, and hence affects the vibrations very slightly. It only affects the relative intensities, and even this effect is minimal. We can therefore simplify our discussion by considering only the Br based Grignard, and assume the I analogue behaves similarly, unless stated otherwise. Changing the relative arrangements of the atoms does change the shape slightly, and often results in the appearance/disappearance of peaks. For example, going from 1to to 1ts (bringing the terminal methyls onto the same Mg center), we observe the disappearance of a major stretching frequency at 557 cm-1 shown below.

1to 557 cm-1

This vibration shows a concerted motion of both Mg centers in a single vibration (Mg-C stretch). After closer inspection of the vibrations of 1ts, it appears that the Me2Mg and Mg(OEt2)2 groups vibrate independently, and the two Mg atoms never move together in the same major stretching vibration. This may be related to the bent structure of the 1ts isomer, because the 1bs isomer (which contains a planar bridge), in which the methyl groups are in the bridging positions and the Bromides are on the same Mg atom exhibits a large bridge distortion at 297 cm-1 which shows the two Mg atoms clearly involved in stretches.

1bs 297 cm-1

Since we wish to study the major species present in the Schlenk equilibrium, we will focus on the structures containing halide bridges (1to and 1ts). Their major vibrations are shown below.

The first thing to note is that the position of the methyl group does not influence the frequency of the C-H related vibrations very much. The largest difference (40 cm-1) is for the C-H wag, which considering that the error on the frequency is as high as 10%, is not that bad. It is difficult to compare Mg based vibrations between the two structures because there are very little that match. The strong distortion of the bridge in 1to at 557 cm-1 is similar to the distortion at 360 cm-1 in 1ts. These two have a very large difference in frequency, even larger than the 10% error on the calculation. However, this difference can also be attributed to the fact that the vibrations are quite different, even though they both involve a distortion of the halide bridge. Such a vibration is also apparent in the 1bo isomer, where the double bridge is formed by the two methyl groups. The vibration below is quite similar to the two evoked above. However, even though the methyl groups are in the bridge, they move a lot more than the case in which the Br are the bridging atoms. The conclusion is that the Br atoms move very little in vibrations, and this is seen across the whole spectrum (apart from the very low frequencies, below 100 cm-1), and as predicted before, can even be extented to the Iodine analogues.

1bo 297 cm-1

NBO analysis

Charge

The NBO analysis was performed on all of the molecules of interest, with the LanL2DZ basis set, and the pop=(full,nbo) keywords. This allows us to see the charge on the atoms in the dimer, a useful feature if we want to guess how nucleophilic the methyl groups are in each dimer. The nucleophilicity will also depend on how deep the charge lies, or in other words how accessible it is. Molecular orbitals provide a good picture of this, and they are what we will use to analyse how easy it is for the methyl groups to attack electrophiles. However, we first show the charge on the carbon in the methyl group, according the its position.

| Anion | Bromide | Iodide | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure |

| |||||||

| Charge on Me | -1.388[41] | -1.366[42] | -1.435[43] | -1.448[44] | -1.395[45] | -1.358[46] | -1.443[47] | -1.450[48] |

The general trend observed is that the magnitude of the charge increases as the methyl groups move into a bridging position. This may be due to the increased Mg-C bond length from going from the terminal to the bridging position (see analysis below). This increase in bond length may mean that any charge on the carbon is more localised on the carbon than on the Mg.

Bridge

Bridges in electron deficient systems can lead to bonding modes in which 3 centers share 2 electrons.[49] This is most common in group 3-based alkyl compounds, where trialkyl compounds dimerise, forming a double bridge, similar to the compounds being investigated. The NBO analysis of the terminal methyl dimers suggest that each Mg-Br-Mg unit contains 4 electrons, leading to the conclusion that the 3c-2e theory does not apply for the case where the halides are bridging. This can be rationalised by the fact that the halides have near-filled valence orbitals, and can easily form a single bond with one Mg center, and a dative bond with another Mg. Close inspection of the NBO of the 1to compound shows that this is indeed the case, with each Br atom forming two bonds with two different Mg atoms, and in both bonds, the Br atom contributes to more than 93% of the bond.

(Occupancy) Bond orbital/ Coefficients/ Hybrids

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1. (1.97043) BD ( 1)Mg 1 -Br 2

( 6.69%) 0.2587*Mg 1 s( 24.38%)p 3.10( 75.62%)

-0.4915 -0.0476 -0.3481 -0.0236 0.7763

0.0735 -0.1613 -0.0212

( 93.31%) 0.9660*Br 2 s( 28.38%)p 2.52( 71.62%)

-0.5327 -0.0008 0.5772 0.0002 -0.5589

-0.0006 0.2659 0.0015

2. (1.97007) BD ( 1)Mg 1 -Br 3

( 6.48%) 0.2546*Mg 1 s( 23.20%)p 3.31( 76.80%)

-0.4793 -0.0480 -0.4065 -0.0235 -0.5902

-0.0447 -0.4995 -0.0483

( 93.52%) 0.9671*Br 3 s( 28.43%)p 2.52( 71.57%)

-0.5332 -0.0012 0.6138 0.0011 0.3276

-0.0003 0.4813 0.0020

3. (1.96344) BD ( 1)Mg 1 - C 13

( 10.90%) 0.3302*Mg 1 s( 49.58%)p 1.02( 50.42%)

0.7010 -0.0662 -0.3062 -0.0230 0.1710

0.0181 -0.6148 -0.0496

( 89.10%) 0.9439* C 13 s( 27.72%)p 2.61( 72.28%)

0.0001 0.5253 -0.0348 0.2343 0.0103

-0.2245 -0.0156 0.7835 0.0584

4. (1.97061) BD ( 1)Br 2 -Mg 6

( 93.46%) 0.9667*Br 2 s( 30.87%)p 2.24( 69.13%)

0.5556 0.0007 0.6091 0.0001 0.3211

-0.0001 0.4661 0.0002

( 6.54%) 0.2558*Mg 6 s( 23.55%)p 3.25( 76.45%)

0.4826 0.0503 -0.4155 -0.0357 -0.5823

-0.0538 -0.4949 -0.0608

5. (1.97088) BD ( 1)Br 3 -Mg 6

( 93.34%) 0.9661*Br 3 s( 31.29%)p 2.20( 68.71%)

0.5593 0.0009 0.5843 0.0002 -0.5368

-0.0007 0.2399 0.0031

( 6.66%) 0.2581*Mg 6 s( 22.59%)p 3.43( 77.41%)

0.4730 0.0468 -0.3548 -0.0244 0.7852

0.0641 -0.1619 -0.0268

We can also see from this that the Mg atoms are sp3 hybridized, and the Br atoms are hybridized between sp2 and sp3 at approximately sp2.4. This shows that the dimers with bridging halides do not form 3c-2e bonds. The dimers with bridging methyl groups are less clear-cut. They show two regular 2c-2e bonding between one Mg and one C atom. The remaining interactions that the Mg atoms are involved in are with the adjacent Br atoms. Confirming or not the existence of a 2c-3e bond is therefore difficult.

(Occupancy) Bond orbital/ Coefficients/ Hybrids

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1. (1.85639) BD ( 1)Mg 1 - C 2

( 6.97%) 0.2640*Mg 1 s( 41.54%)p 1.41( 58.46%)

-0.6445 -0.0054 -0.6327 -0.0428 -0.1740

-0.0316 -0.3869 -0.0386

( 93.03%) 0.9645* C 2 s( 37.31%)p 1.68( 62.69%)

-0.0001 -0.6100 0.0311 0.0393 -0.0012

-0.0117 0.0026 0.7882 0.0635

2. (1.99094) BD ( 1)Mg 1 -Br 13

( 11.37%) 0.3372*Mg 1 s( 40.97%)p 1.44( 59.03%)

0.6401 -0.0004 -0.4637 -0.0136 -0.6107

-0.0340 -0.0285 -0.0058

( 88.63%) 0.9414*Br 13 s( 40.49%)p 1.47( 59.51%)

0.6363 0.0008 0.4367 0.0052 0.6358

0.0086 -0.0054 -0.0001

3. (1.98841) BD ( 1) C 2 - H 40

( 61.90%) 0.7868* C 2 s( 21.41%)p 3.67( 78.59%)

-0.0001 0.4623 0.0194 0.2206 -0.0040

-0.7896 0.0304 0.3355 -0.0150

( 38.10%) 0.6172* H 40 s(100.00%)

1.0000 -0.0007

4. (1.98353) BD ( 1) C 2 - H 41

( 61.84%) 0.7864* C 2 s( 19.79%)p 4.05( 80.21%)

0.0000 -0.4443 -0.0229 0.7806 -0.0130

-0.2067 0.0123 -0.3865 0.0196

( 38.16%) 0.6178* H 41 s(100.00%)

-1.0000 -0.0003

5. (1.98432) BD ( 1) C 2 - H 42

( 62.09%) 0.7880* C 2 s( 21.31%)p 3.69( 78.69%)

-0.0001 0.4612 0.0205 0.5834 -0.0043

0.5762 -0.0241 0.3371 -0.0186

( 37.91%) 0.6157* H 42 s(100.00%)

1.0000 0.0004

6. (1.85510) BD ( 1) C 3 -Mg 6

( 93.02%) 0.9645* C 3 s( 37.27%)p 1.68( 62.73%)

0.0001 0.6097 -0.0305 0.0314 0.0003

0.0634 -0.0022 0.7863 0.0637

( 6.98%) 0.2642*Mg 6 s( 41.65%)p 1.40( 58.35%)

0.6454 -0.0017 -0.6303 -0.0468 -0.1707

-0.0245 -0.3912 -0.0350

Molecular orbitals

As with the vibrations, the focus of the MO study is mainly on the species in which the halides are bridging. Predictably, the HOMO and HOMO-1 of the 1to compound show the majority of the electron density on the methyl groups and along their C-Mg bonds. In both cases, there is a lobe on the methyl group pointing outwards, and since these are relatively high-lying occupied orbitals, it is not unreasonable to state that these orbitals are responsible for reacting with electrophiles.

| 1to HOMO | 1to HOMO-1 |

|---|---|

|

|

| 1to HOMO-10 | 1to HOMO-11 | 1to HOMO-12 |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

As we make our way towards deeper seated orbitals, we encounter bonding and antibonding interactions between the bromides. In the pictures below, orbitals involving the Mg atoms in the bridge are also clearly apparent suggesting some degree of bonding. We also observe that there are more bonding than antibonding orbitals. Considering the fact that the NBO tells us that the Mg-Br-Mg-Br moiety contains 8 electrons, these orbitals do not provide the whole picture of the bonding within the bridges. The additional bonding orbitals are most likely found in obitals lower in energy. However, due to time constraints/lack of computational power, I was not able to compute all the orbitals of the molecule.

| 1to HOMO-3 | 1to HOMO-4 | 1to HOMO-5 | 1to HOMO-6 | 1to HOMO-9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| Antibonding | Bonding | Antibonding | Bonding | Bonding |

When the methyl groups are on the same Mg atom, the structure distorts slightly, but the major orbitals of interest are still present. For example, the HOMO is still situated on the methyl groups, and the HOMOs a little further down still involve bromide lone pairs.

| 1ts HOMO | 1ts HOMO-4 | 1ts HOMO-5 |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

When the methyl groups are in the bridging positions their charge may be enhanced, but it appears from the HOMO and HOMO-4 that the charge may be deeper-lying than in the cases where they occupy the terminal positions. This suggests that they may be less reactive towards electrophiles, since their charge is more shielded by other occupied orbitals.

| 1bo HOMO | 1to HOMO-4 |

|---|---|

|

|

When the methyl groups are bridging and the bromides are on the same Mg atom, this effect is even more pronounced, and HOMO does not involve the methyl groups any more. In fact, the HOMO and HOMO-1 orbitals are localised on the bromides, and the methyl groups start to show electron density on them on the HOMO-2 and HOMO-3. In the HOMO-4, there is more electron density on the methyl groups than on bromides. However, the fact that the HOMO-4 is lower in energy than the HOMO, it can be deduced that nucleophilic attacks will be preferentially performed by the bromides. This, combined with the fact that the bridging methyls share their lone pairs in the bridges, which contain only 2 electrons each, makes it difficult for the methyl groups to act as the nucleophiles.

| Dimer Type | 1to | 1ts | 1bo | 1bs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy of HOMO (Hartrees) | -0.206 | -0.175 | -0.245 | -0.217 |

| Localized on Me? | Yes, even HOMO-1 | Yes | Yes, but also on the Br | No |

Conclusions

In terms of the structures, we can be confident that we have found the most likely structures that the dimers would adopt (except the 2ts), given the fact that the vibrational analysis are satisfactory, and that our the basis structure is in good agreement with the literature. From the molecular orbitals and NBO analysis we have managed to identify the bonding mode of bridging halides as a regular 2c-2e type bonding, whereas the methyl bridges are a little less obvious. In theory, there are in fact 2 electrons for 3 centers, but the NBO analysis does not show clear Mg-C-Mg bonds, so confirming this type of bonding would be somewhat erroneous. NBO analysis has also allowed us to identify the charge on the methyl groups, and make predictions as to their nucleophilicity.

References

- ↑ https://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/b/b7/PIERRE_BH3_OPT.LOG

- ↑ https://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/b/b8/PIERRE_BH3_MO.LOG

- ↑ https://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/d/d6/PIERRE_BH3_FREQ.LOG

- ↑ https://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/5/53/PIERRE_BCL3_OPT.LOG

- ↑ A.C. Testa, Spectrochimica Acta Part A, 1999, 55, 299–309

- ↑ https://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/b/bf/PIERRE_BCL3_FREQ.LOG

- ↑ P. Hunt, Molecular Orbitals of BH3, http://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/hunt/teaching/teaching_comp_lab_year3/5a_molecular_orbitals.html, accessed: 09/03/10

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4419

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4420

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4422

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4421

- ↑ Atkins, Overton, Rourke, Weller, Armstrong, Inorganic Chemistry, ed. OUP, 2006, 551

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4423

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4424

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4429

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4430

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4428

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4431

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 F. A. Cotton, D. J. Darensbourg, S. Klein and B. W. S. Kolthammer, Inorg. Chem., 1982, 21, 294

- ↑ F.A. Cotton, D.J. Darensbourg, S. Klein and B.W.S. Kolthammer. Inorg. Chem. 1982, 21, 2661

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 D.J. Darensbourg, R.L. Kump, Inorg. Chem. 1978, 17, 2680-2682

- ↑ P. Lickiss, 2nd Year Main Group Chemistry, 2009

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4497 (LanL2MB) http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4502 (LanL2DZ)

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4501 (LanL2MB) http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4503 (LanL2DZ)

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4499

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4500

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4504

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4631

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4529

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4506

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 L.M. Pratt, I.M. Khan, Journal of Molecular Structure (Theochem), 1995, 333, 147-152

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4529

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4587

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4582

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4585

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4584

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4586

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4581

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4529

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4583

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4559

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4560

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4557

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4558

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4553

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4554

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4555

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4556

- ↑ IUPAC Gold Book