Rep:Mod:opus1011

Module 2: BONDING ANALYSES USING AB INITIO AND DENSITY FUNCTIONAL TECHNIQUES

Adeleke Adekunle Francis

00516555

1. Abstract

This work was undertaken in order to communicate the VERACITY! and limitations of computational analysis.

2. Introduction

In its simplest form, ĤΨ = EΨ, the Schrödinger equation is an elementary formula of quantum mechanics. It is a fundamental postulate or an axiom, thus it cannot be derived, but its veracity is well established. H is a linear, hermitian operator that acts on a function to produce that function multiplied by a constant. Ψ is used to represent this function, called an eigenfunction and the constant produced is the eigenvalue. Ψ is a wavefunction since it describes the properties of an electron-wave.[1]

In its more rigorous form, , Schrödinger equation is a differential equation for the wavefunction. The wavefunction of a particle is defined as the amplitude of the matter wave. The square of the wavefunction (or the wavefunction multiplied by its complex conjugate, Ψ×Ψ*) has probabilistic interpretations, Ψ(x)×Ψ(x)*dx is the probability of finding a particle located between x and x+dx.[1]

The Schrödinger equation is usually expressed as an eigenvalue problem i.e. the problem is to find the wavefunction and eigenvalue that fits a particular operator. Thus the Schrödinger equation imposes restrictions on the form of the wavefunction. A wavefunction must be continuous (so it is possible to take a second derivative), single-valued and finite.[2] The purpose of finding the wavefunction of a particle or a system is that once it is known, any physical observable can be derived. The solutions to Schrödinger equation are wavefunctions. An exact solution to the Schrödinger equation has been formulated for the hydrogen atom, the wavefunctions obtained are called orbitals. As described by Grant et al, "wavefunctions are not supernatural functions...[those] obtained for the hydrogen atom are atomic orbitals which are merely three-dimensional functions".[3]. Thus from the wavefunction or atomic orbital of the hydrogen atom, physical observables like energy can be calculated for systems with one electron, hydrogenic systems.

2.1. Molecular orbitals

The molecular orbital or wavefunction of a molecule with n atoms can be defined as the product of n atomic orbitals. This is known as the orbital approximation, Ψ = Φ1Φ2...Φn. In this case atomic orbitals are defined as a function for one electron in the molecule, which can be approximated as the hydrogenic atomic orbital, therefore Φ1Φ2...Φn is the linear combination of atomic orbitals (LCAO).

3. How are molecular orbitals obtained?

The following derivations were adapted from ref. 3 and they present the system of thinking involved in obtaining molecular orbitals.

The Hartree-Fock method is a well defined method for MO calculations. If the Schrödinger equation for the hydrogen atom is simplified i.e. if written in Planck's unit, unit of length is Bohr radius and electronic charge, e, and electronic mass, me, are taken as unity, then it becomes . The kinteic energy term in this equation is and the potential energy (electron-nucleus attraction) is . The molecular wavefunction of H2 is slightly more complex, it takes the form . The energy produced is the electronic energy, the energy for nuclear-nuclear repulsion, , where R is interatomic distance. This equation (in this form) is however not useful (for the purposes of subsequent calculations) because it specifies the summation of two H+ wavefunctions plus an electron replusion term, , therefore it is the total hamiltonian of the whole H2 system.[3]

However in a similar fashion, the hamiltonian can be written as a one-electron equation (i.e. looking from the perspective of one electron and indicating all its interactions rather than looking at the system as a whole) with kinetic energy, electron-electron repulsion, electron-nuclear attraction. The kinetic energy term is , the electron(i)-nuclear(v) attraction term is . The kinetic term and the electron-nuclear attraction term can be combined and denoted as HN if no other electrons were present, this would be sufficient to specify the hamiltonian of the system.[3]

For two-electron system, with , , separated by r12, their repulsion is given as , where is the charge distribution of electron (1) if is real or if is complex. Also, is the charge distribution of electron (2). Therefore the one-electron (not be mistaken for that of a single-electron system but as described above) is given as . This mathematical formulation is correct except for the fact that orbital wavefunctions are not simple products but determinants. In order to introduce the determinantal form of the wavefunction, the so-called Hartree-Fock equations (full self-consistent field equations) are defined as HSCFi = ii where HSCF is given as HSCF = ( ); where and . Kj are exchange terms due to Pauli exclusion principle, therefore the wavefunctions are determinantal. Therefore coloumbic interelectron interactions are specified.

The mathematics is exciting and the very important thing to note is that the Hamiltonian now contains ; the value to be determined! Since , therefore Cik must be known (origin of the self-consistency. The procedure is therefore to guess a value for Cik. The determinantal equation det|HSCF - εSik | must be zero, therefore a solution is obtained for ε, this is substituted into the secular equations to produce better values of Cik. This process is repeated until Cik from two consecutive cycles are same i.e when the results are self-consistent. The best value of Cik is then used to obtain the self-consistent molecular orbitals. Ab initio methods utilise full Hartree-Fock self-consistent field operators. More accurate semi-empirical methods can also be used.

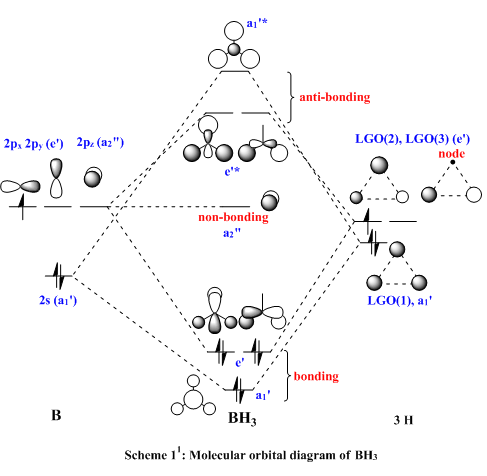

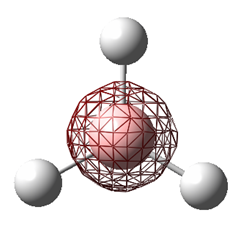

4. Structure and Bonding of BH3

BH3 is a borane or boron hydride i.e. a compound of boron and hydrogen. The boron atom has six electrons. BH3 is susceptible to nucleophilic attack, it forms adducts with Lewis acids (species with lone pair of electrons). Figure 1 illustrates the fact that the low energy LUMO is non-bonding orbital, therefore a nucleophilic attack which supplies two electrons readily binds to BH3 so that the boron forms an octet.[4]

Although BH3 can be observed in the gas phase, it readily dimerises to diborane, B2H6, in the absence of a Lewis acid. Boron has only three outer electrons so it can only form 3 bonds, then it has 6 electrons. The VSEPR model fails to explain the bonding situation in diborane. In B2H6, a 3c-2e bonding was proposed (by H.C. Longuet-Higgins) to exist across a bent B-(μ-H)-B bond. Molecular orbital theory supports this bonding scheme.

The quantum mechanical calculations are carried out as follows;

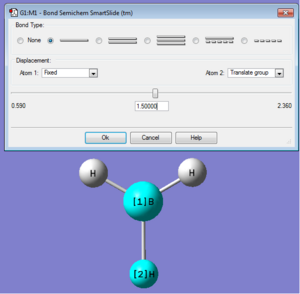

4.1. Creating a molecule of BH3

A molecule of BH3 was created on GuassView 5.0 from the trigonal planar BY3 (BH3 is default) template. All three equivalent B-H bond lengths were changed from the default 1.18Å to 1.50Å. The result of this process is shown below;

Activity: Right-click on image→Measurements→Click on Distance (or angle) Measurements→Double-click on image to start all measurements→Choose two atoms to obtain interatomic distance or three atoms to obtain bond angle. Result is a bond length of 1.50Å and a bond angle of 120o. With this method, the bond length are displayed with higher significant numbers (not higher accuracy! as accuracy is to 2 sig. fig., this is only useful for qualitative comparison). Displayed measurement can be deleted for ease of visualisation: Right-click on image→Measurements→Delete all measurements.

4.2. Optimising a molecule of BH3

An optimisation of the created BH3 molecule was performed. A quantum mechanical method was used for the optimisation process. The calculation was done at the B3LYP/6-31G level (6 means that there are 6 primitive Gaussian functions comprising each core atomic orbital basis function i.e. the orbitals are Slater-type orbitals which are obtained by fitting exponential function to atomic wavefunctions but integrals were calculated by fitting 6 Gaussian functions to the exponential functions. 31 means that the valence orbitals contain two basis functions each and the 3 denotes the linear combination of 3 primitive Gaussian functions, and the other basis set has 1 Gaussian function).[3] The keyword that prompts this calculation is # opt b3lyp/6-31g geom=connectivity.

The result DOI:10042/to-7534 is displayed below;

OptBH3 |

Activity: Information about the bond lengths and bond angles was obtained as described above. The Result of the optimisation step is a bond length of 1.19Å and a bond angle of 120o.

Note: The optimisation process has reduced the bond length by 0.31Å to 1.19Å similar to the starting bond length, therefore the reason for increasing the bond length in the first step is to show the power of the optimisation process. Optimising a structure to obtain a bond length of 1.19Å from 1.18Å is unimpressive and undiscernable.

4.3. Analysing the optimised BH3 molecule

As an alternative to the process described in the 'activity' section, geometric information can was obtained from the GuassView interface by viewing the data from the optimisation process or by using the 'inquire' button. From invoking the 'inquire' button and clicking on two atoms, a bond length of 1.19Å was obtained for the optimised geometry. In this manner, a value of 1.18Å was obtained for the bond length of a 'fresh' BH3 molecule and after it was changed to 1.50Å. This fact is mentioned in order to emphasize the accuracy to which the bond lengths are measured. A bond angle of 120o was obtained for the optimised structure.

The data from the optimisation step is presented below;

| File Name | BH3(631G)OPT |

| File Type | .log |

| Calculation Type | FOPT |

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 6-31G |

| Charge | 0 |

| Spin | Singlet |

| E(RB+HF-LYP) | -26.60595934 a.u. |

| RMS Gradient Norm | 0.00000298 a.u. |

| Dipole Moment | 0.0000 Debye |

| Point Group | D3h |

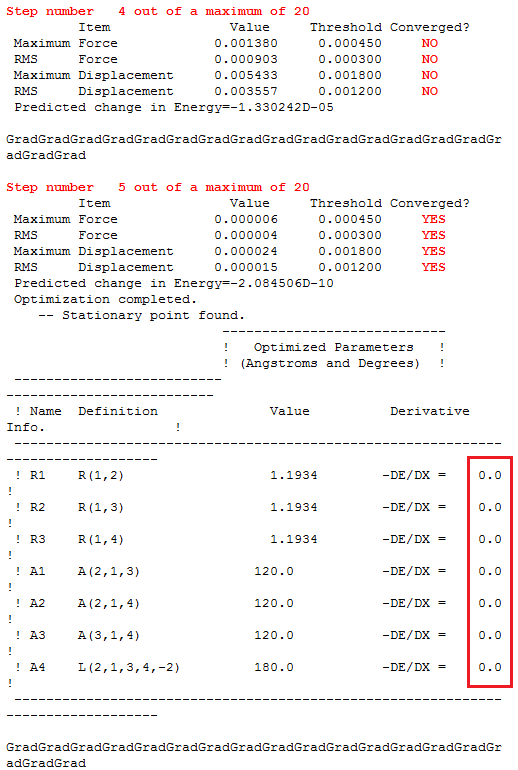

The 'real' output below shows that the structure was optimised i.e. the energy was minimised.

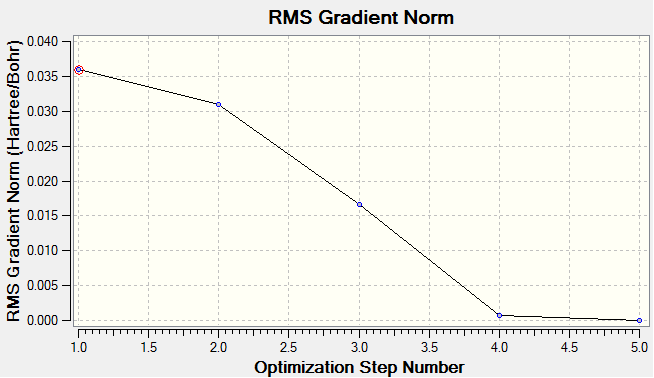

It will be illustrated later that optimisation is complete after five steps, but if this fact is accepted then the output data makes sense. The forces or energy gradient in step 4 are still above 0.001, an indication that the optimisation is not complete. This assertion is supported by the 'NO' in the converged section. This means that the energy gradient is not at the lowest possible value. At step five, all the forces are well below 0.001 by three order of magnitude, this fact and the resounding 'YES' confirm the convergence. The energy gradient is almost zero, so further change in structure can lead to a lower energy.

4.4. Understanding optimisation part a

The optimisation plot shows how the structure was optimised and also the energy of the structures at each optimisation step. Also information about the energy gradient at each step is presented, a gradient close to zero means that the structure is at a minimum.

|

|

| STRUCTURE AT STEP 1 | STRUCTURE AT STEP 2 | STRUCTURE AT STEP 3 | STRUCTURE AT STEP 4 | STRUCTURE AT STEP 5 | |||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

The optimisation plots shows that the total energy of the system decreases per step (becomes more negative), also the energy gradient decreases per step. The decrease in bond lengths show that change in nuclei positions affects the energy of the system. The gradient going from 1 to 2 (here bond length changes by 0.09Å) is lower than 2 to 3 (here bond length changes by 0.13Å). The bond lengths illustrated on the diagram do not report with enough accuracy to distinguish between the two structure. The 'inquiry' returns the bond length of structure 4 as 1.19048Å and that of structure 5 as 1.19336Å. An increase in bond length! But total energy (Hartree) remains practically unchanged (-26.6059 (for 4) to -26.606 (for 5)), and energy gradient (Hartree/Bohr) decreases (from 6.90×10-4 (for 4) to 2.98×10-6 (for 5)). Note: Bond lengths and energy have been quoted to unreasonable accuracy (accuracy is as stated above, to 2 sig. fig.). This is done for qualitative reasons, i.e. to show the optimisation step 5 is not redundant.

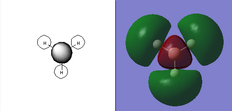

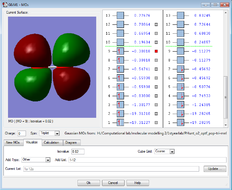

4.5. Molecular orbitals of BH3

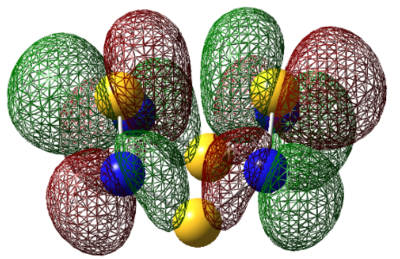

In figure 1, the qualitative MO of BH3 was presented. In this section the computed or quantitative MO will be generated. The result DOI:10042/to-7582 of the computational analysis, at B3LYP/6-31G level, is displayed below. The keyword that prompt this is # b3lyp/6-31g pop=(nbo,full) geom=connectivity.

| HOMO-2 | HOMO-1 | HOMO | HOMO |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| LUMO | LUMO+1 | LUMO+2 | LUMO+2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note: The MO scheme presented in figure 1 arranges the MO in such a way that the 3a1'* antibonding MO is the highest in energy and the 2e'* relatively lower the energy. The reasoning for this ordering was that a

-

antibonding interaction was more destabilising than a

-

antibonding interaction. However if the '.log file' ('.chk file' is for viewing the MO's but the '.log file provides useful info.) from the MO calculations are opened and an attempt is made to view the MO, no orbitals are displayed but the ordering presented here (thumb picture) is seen. In the ordering displayed here, the 3a1'* antibonding MO is slightly lower in energy than the 2e'* antibonding MO. The reason for this is explained below.

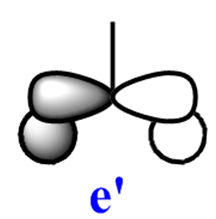

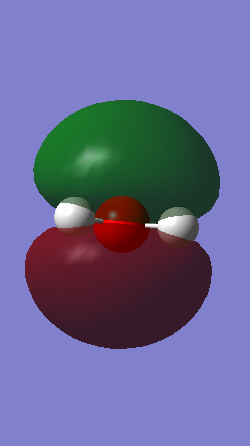

The qualitative (q-MO henceforth) MO's bear remarkable resemblance to the computed MO (c-MO henceforth). The 1a1' MO is the lowest in energy, it is due to the 1s Boron atomic orbital, the q-MO is correct and presents a clear representation of the c-MO. The next MO is the 2a1'. The q-MO shows that boron contributes more to the bonding MO since it is more electronegative than hydrogen. The c-MO is totally symmetric, it extends over the whole molecule. The doubly degenerate, highest occupied 1e' q-MO is representative of the real picture (Why? see 'deductions'). The next MO is the non-bonding 1a2". The q- and c-MO's are practically equal. It is the lowest unoccupied MO. The energy of this MO is still relatively low. This is the reason for it's susceptibility to attack by nucleophilse or lewis bases to form adducts. The next MO (following the computed ordering) is the 3a1'* antibonding MO. The q-MO reveals the fact ('fact' being the c-MO) that boron makes a lesser contribution to the antibonding MO. However q-MO does not reveal the fact (revealed by c-MO but not on this 2D image) that the orbital on boron more diffuse in the C3-axis than expected. The first of the doubly degenerate 2e'* antibonding MO is remarkable. The p-orbital on boron is not planar as suggested by the q-MO but it bends away from orbitals with opposite parity (there is no electron density between them). The doubly degenerate 2e'* antibonding MO is even more remarkable. The qualitative MO is good (p-lobe slight grazes an orbital of opposite parity, this is a drawing mistake, there is no electron density between them!) but fall short of a full description. In the computed MO, orbitals of like parity (green) interact and are thus more diffuse.

As to the observed change in ordering, the reason for this might be that there are three unfavourable interactions in 3a1'* but four in 2e'*. This explanation is only suitable for the first 2e'* MO. The c-MO of 2e'* suggests some slightly bonding interaction which prompts the question of why it is higher in energy than 3a1'* or degenerate to the first 2e'* MO! The relative energies of these MO's suggest they are very close in energy. The quantum mechanical technique and basis set used (B3LYP/6-31G) are accurate and BH3 is a small molecule, but one can conceive that a more accurate method of solving the wavefunction might yield a different ordering i.e. one displayed in fig. 1. For this reason, the observed change in ordering is interesting but not alarming.

Deductions: In this case the qualitative MO's were accurate, but more information can be gained from a qualitative MO if it is interpreted in light of a computed MO i.e. if orbitals of like-parity are next to one another, they are diffuse and they interact. Orbitals of opposite parity bend away from one another. For example (an organic example!, it is common to represent the orbitals on C and O of a carbonyl compound as being localised on these atoms, but it is a bonding MO and hence it is diffuse between the atoms. Also the MO are not just straight orbitals (with opposite parity) but they bend away from each other (hence the 107o Bürgi-Dunitz angle of attack). Orbitals are not just balls and lobes, they interact, think chemically!

4.6. NBO analysis of BH3

Information about analysing data from NBO calculations were retreived from ref. 5.

From section 4.5, it was observed that molecular orbitals (total) extend all the BH3 molecule. This is useful in describing stability and how molecules interact. However the useful (but unrealistic) detail of two-centre two electron bonding is lost. Natural bond orbitals analysis seeks to regain this formalism from the MO, thus Natural bond orbitals are bond localised molecular orbitals (linear combination of atomic orbitals). The keyword from the previous MO calculation includes a 'full NBO' analysis.[5]

One information that can be retrieved from NBO analysis are the NBO atomic charges (natural atomic charges), these are "nuclear charge minus summed natural populations of NAO's (natural atomic orbitals) on the atom".[5] Therefore from this description, a highly positive NBO charge number means that the nuclear charge is greater than the summed natural populations of NAO's on the atom, so the atom is highly positive and/or even electron deficient (at least compared to the other atoms). A highly negative NBO charge number means that the nuclear charge is lesser than the summed natural populations of NAO's on the atom, so the atom is highly negative i.e. there is electron density on this atom.

The boron atom has a green colour indicating a highly positive charge, so as expected boron is highly positively charged, electron deficient and lewis acidic. The hydrogen atoms are dark red indicating a highly negative charge.

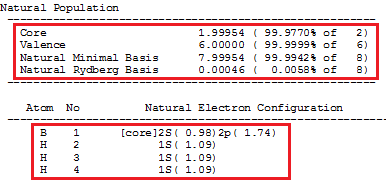

There are other informations that can be retrieved from the NBO analysis. The first is the natural population analysis (NPA). This section of the data is divided into two parts. The first contains values for the occupancy of the natural atomic orbitals.

1 heralds the start of the NBO analysis data. 2 shows that the data displayed are NAO occupancies. 3 is explained as follows; NAO stands for natural atomic orbitals. Atom: The type of atoms are displayed, B and H. No: Atom numbering. lang: Types of angular momenta (s, px, py, pz). Type(AO): Label for the hydrogen-like atomic orbitals, Cor are the inner, core orbitals, Val are the outer valence orbitals and Ryd are the Rydberg orbitals, these are very diffuse orbitals with higher principal quantum numbers, n, than the atoms' valence orbitals. The occupancy shows the population of electrons residing on the orbital.

The next part of the NBO data is a summary of the first. It displays the total core, valence, and Rydberg occupancy/population on each atom.

The result of this is consistent with the fact that boron has 5 electrons and three hydrogen atoms have three, so the total number of electrons equal 8.

The next part of the NBO data is the summary of the natural minimal basis and natural Rydberg basis populations. The natural minimal basis includes the core and valence NAO's, therefore this data shows that the core and valence orbitals account for >99% of the molecular charge distribution, there is negligible contribution from the Rydberg NAO's.

The second part of this section shows the effective valence electron configuration. This shows that the valence configuration of boron is (2s)0.98(2p)1.74. This is an approximation of the sp2 hybridized configuration of the boron.

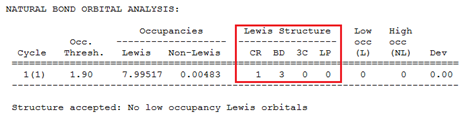

The next section provides the NBO natural Lewis structure. It shows that there are no three centre bonds (3C), no lone pairs (LP) and that monoborane has 3 two two-centre bonds (BD).

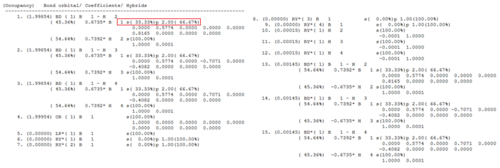

Information about hybridisation can also be obtained (analysis already provided in instruction manual)

This confirms sp2 B-H hybridisation, and the p-empty orbitals.

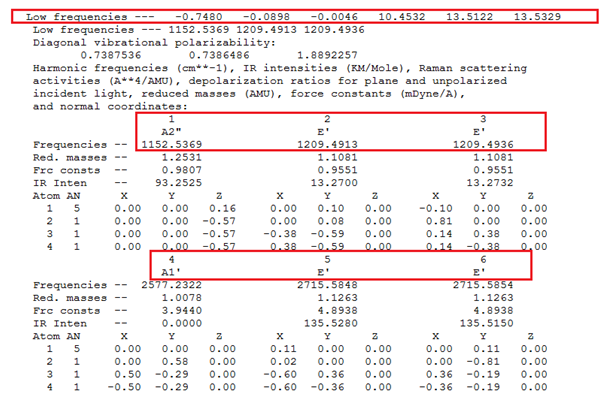

4.5. Vibrational Analysis of BH3

The vibrational spectrum of BH3 with D3h symmetry was calculated. The second derivative a graph of potential energy against internuclear separation provides this information. The IR and Raman modes can also be deduced from this calculation. The keyword for this calculation is # freq b3lyp/6-31g geom=connectivity pop=(full,nbo). The result

https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/9/91/FRANCIS_BH3_FREQ%28TRIAL_3%29.LOG is displayed below, but before analysing this, a preliminary calculation of the molecular vibrations will be made. In the preliminary calculations, the reducible representation of the vibrational modes will be produced (number of atoms unmoved by each symmetry class), then the contribution to the trace of each class is considered, after this the reduction of the reducible representation follows. Finally the irreducible representations due to vibrations and rotations are removed.[6]

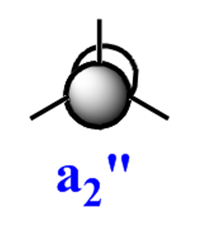

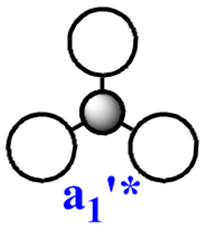

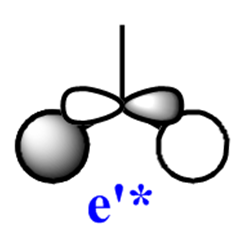

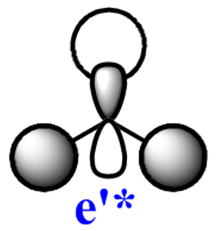

This result of the frequency analysis are as follows;

| No. | Form of vibration | Frequency/ cm-1 | Intensity | Symmetry (D3h Point group) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

1153 | 93 | A2" (Totally asymmetric bend) | |||

| 2 |

|

1210 | 13 | E' (Degenerate symmetric bend) | |||

| 3 |

|

1210 | 13 | E' (Degenerate asymmetric bend) | |||

| 4 |

|

2577 | 0 | A1' (Totally symmetric stretch) | |||

| 5 |

|

2715 | 136 | E' (Degenerate asymmetric stretch) | |||

| 6 |

|

2715 | 136 | E' (Degenerate symmetric stretch) |

As expected, vibration no. 4 is not IR active because there is no change in the dipole moment. Therefore the full description of the vibrational modes of BH3 is: vib(BH3) = A2" (IR, pol) + 2E' (IR, depol) The data from the ".log file" (see below) agrees with this.

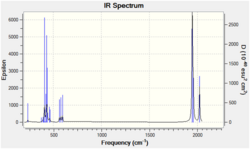

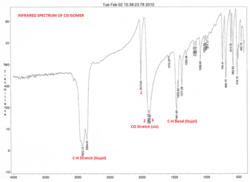

The IR spectrum is presented below;

As expected, the spectrum shows three peaks. The peaks due to degenerate asym. and sym. bends overlap, the same is true for the stretches. As previously discussed, monoborane is electron deficient and in the absence of a lewis base or nucleophile, it dimerises but it is observable in the gas phase.[4] Kawaguchi et al[7] reported the gas-phase infrared spectrum of BH3. The monoborane was obtained by photolysis of B2H6 by ArF laser. There is much difficulty in obtaining a pure infrared spectrum of monoborane due to BH and BH2 contamination. The reported bands are as follows (range; ref. 7(expt); ref. 7(HF/6-31G*) / cm-1; Vib no. 1 (590-1560; 1125; 1225), Vib no. 2,3 (1134-1764; 1604; 1305), Vib no. 5,6 (2470-2976; 2808; 2813). The experimental range is very wide, also the accuracy of the frequency in this computed spectrum and one in ref. 7 are about 300cm-1. Therefore the data have medium accuracy and but low precision.

Other Information: In eh calculation scheme presented above, the irreducible representation due to rotation and translation were removed. Therefore if the computation performed is correct, the ".log file" should show that the frequencies due rotation and translation is small (~10cm-1).

The highest frequency due to rotation and translation is ~13, which is ~100× smaller than the lowest vibrational frequency. The vibrational point groups are annotated correctly.

5. Using Pseudo-potentials and Larger basis set

Thallium bromide is the object of this study. The large number of electron of bromine (35) and thallium (81) means there are large amount of orbitals to compute i.e. large amount of integral equations to solve. In addition to the large computational time this takes, much detail is lost due to relativistic effects. Modelling the core electrons with pseudo-potentials alleviates some of these problems. Also a larger basis set is used.

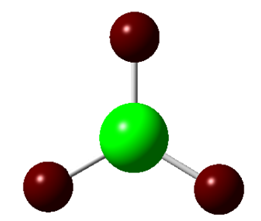

A molecule of TlBr3 was created as described for the BH3 case. The result is shown below;

| Fresh structure | Optimised structure (DOI:10042/to-7713 ) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

The symmetry of TlBr3 was restricted to D3h with 'very tight' tolerance. Geometry optimisation was performed with the following keyword, # opt b3lyp/lanl2dz geom=connectivity, to obtain the structure displayed above. This summary of this calculation is displayed below;

The molecule has retained its symmetry! The bond lengths changed from 0.269nm (preliminary structure) to 0.265nm (optimised structure). Literature (J. Glaser, G. Johansson, Acta. Chem. Scand. A, 1982, 36, 125.) bond length was 0.2512nm (o.05% discrepancy!), there is good agreement. A bond angle of 120o was retained in the optimised structure. The summary file shows that the calculation method was RB3LYP and the LANL2DZ basis set was used. Different basis set use different approximations, therefore using two different basis set in two consecutive step (Or for two calculations) results in an error on the data obtained. For example the ordering of the energies of the molecular orbitals are wrong (this was observed for BH3). Frequency analysis was performed in order to confirm that the structure was optimised to the minima.

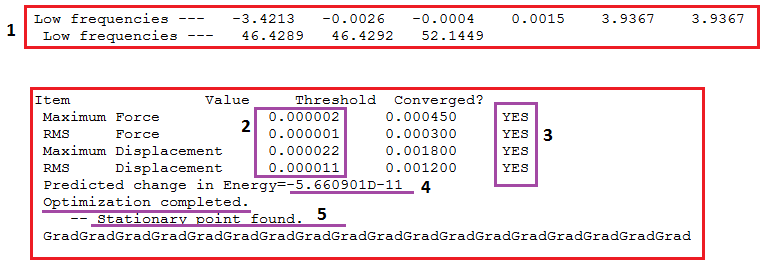

The data DOI:10042/to-7811 from infrared analysis is presented below;

The frequencies are expected for D3h symmetry. The sections of the '.log file' are displayed below;

1 shows that the low frequencies are at least an order of magnitude smaller than the lowest real mode (46cm-1). 2 shows the energy gradients are all smaller than 0.001, a good indication of optimisation. 3 shows that the forces have converged. In 4, the predicted change in energy is negligible. Finally, 5 heralds the stationary point of the energy (or structure) minima. Therefore the structure is a minima.

Gaussview sometimes omit bond if the bond lengths are longer from a defined limit, however chemical intuition shows that there is a bond (and the fact that it has just been drawn!). This module proves that no simplistic definition can be given for the existence of bond as one must include in the definition the various kinds of bonding interactions. One can suggest the following; that a chemical bond is such that there exists an attractive interaction between two atoms, molecules (or chemical species) which results in a lowering of the energies of the resultant species, and these species are usually stable enough to isolate. This attractive interaction is an inverse function of the distance (to different orders) between the two chemical entities and this distance is lower than the sum of their van der Waals radii.

6. Infrared identification of geometric isomers of [Mo(CO)4(L)2]

Ligand disubstituted molybdenum complexes, [Mo(CO)4(L)2], show geometrical (cis/trans) isomerism. These isomers easily be distinguished by infrared spectroscopy. The carbonyl stretching frequencies (2100-1750cm-1) are usually free from interference from absorptions due to other groups. Group theory predicts that the cis-isomer (C2v point group) of a generic complex [Mo(CO)4(L)2] has four carbonyl absorption bands and the trans-isomer (D4h) has only one. In order to save computational time, L = PCl3.

6.1. Structure Optimisation

| Optimisation 1 | Optimisation 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Trans-isomer | DOI:10042/to-7636 | DOI:10042/to-7637 |

| Cis-isomer | DOI:10042/to-7638 | DOI:10042/to-7639 |

6.1.1 Trans-Isomer

First the trans-isomer of [Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2] was created on GaussView. Procedure is as for previous sections. A preliminary optimisation was invoked with the # opt=loose b3lyp/lanl2mb geom=connectivity keyword. Modification of the structure was performed (as per instruction) and a second optimisation was performed with the keyword # opt b3lyp/lanl2dz geom=connectivity int=ultrafine scf=conver=9. The results are displayed below;

| Freshly drawn structure | Structure after Optimisation 1 | Structure after Optimisation 2 |

|---|---|---|

The observed changes are as follows;

| Trans_fresh | Trans_1stOpt | Trans_2ndOpt | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mo-P bond length/ nm | 0.234 | 0.248 | 0.244 |

| P-Cl bond length/ nm | 0.204 | 0.240 | 0.224 |

| Mo-C bond length/ nm | 0.206 | 0.211 | 0.206 |

| C-O bond length/ nm | 0.132 | 0.119 | 0.117 |

| Cl-P-Cl bond angle | 109.5 | 98(approx.) | 99 |

The two Mo-P bond lengths are equal. All the P-Cl bond lengths are equivalent. The P-C bond lengths are equal, as are the CO bond lengths. All Cl-P-Cl bond angles are approximately equal. The ".log file" showed that all the forces converged, this means that the optimisation worked. This is also evident in the changes listed above. The value of the energy gradient were well below 0.001 (orders of magnitude lower).

6.1.2 Cis-Isomer

After creating cis-[Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2]. The first optimisation was invoked with the # opt=loose b3lyp/lanl2mb geom=connectivity keyword. After the resulting structure was modified, a second optimisation was performed with the keyword # opt b3lyp/lanl2dz geom=connectivity int=ultrafine scf=conver=9. The results are displayed below;

| Freshly drawn structure | Structure after Optimisation 1 | Structure after Optimisation 2 |

|---|---|---|

The observed changes are as follows;

| Cis_fresh | Cis_1stOpt | Cis_2ndOpt | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mo-P bond length/ nm | 0.234 | 0.253 | 0.251 |

| P-Cl bond length/ nm | 0.204 | 0.241 | 0.224 |

| Mo-C bond length/ nm | 0.206 | 0.211 | 0.206 |

| C-O bond length/ nm | 0.132 | 0.119 | 0.117 |

| Cl-P-Cl bond angle | 109.5 | 97(approx.) | 99 |

Similar bond lengths and bond angles are equivalent as described above.

6.2. Infrared spectra of the isomers

| IR trans-isomer | IR cis-isomer |

|---|---|

| DOI:10042/to-7649 | DOI:10042/to-7650 |

The infrared spectrum of the isomers are displayed below, these values are compared to experimental data (Year 2 lab report) of the IR spectrum of Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2.

| Trans-isomer (D4h point group) |

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Frequency/ cm-1 | 1950 | 1951 | 1977 | 2031 | ||||||||||||

| Intensity | 1475 | 1466 | 1 | 4 | ||||||||||||

| Symmetry | A | A | A | A | ||||||||||||

| Cis-isomer C1 (C2v) point group) |

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Frequency/ cm-1 | 1945 | 1949 | 1958 | 2023 | ||||||||||||

| Intensity | 763 | 1498 | 632 | 598 | ||||||||||||

| Symmetry | A | A | A | A |

The expected point group of the isomers are indicated above. The Trans-isomer has D4h point group, therefore the symmetry of the IR active mode is Eu. From the summary files, C1 was obtained. However the IR spectrum(/cm-1) shows a double degenerate CO stretch at 1950, the other CO stretches have very low intensity. Experimental result(yr 2 lab report) shows CO stretch at 1889. For the cis-isomer with C2v point group, four CO stretches are expected and indeed four were obtained from the computational analysis. Again a C1 point group was obtained, so all the vibrational mode were A, but they coincide with the expected A1, A1, B1, B2 vibrational modes.

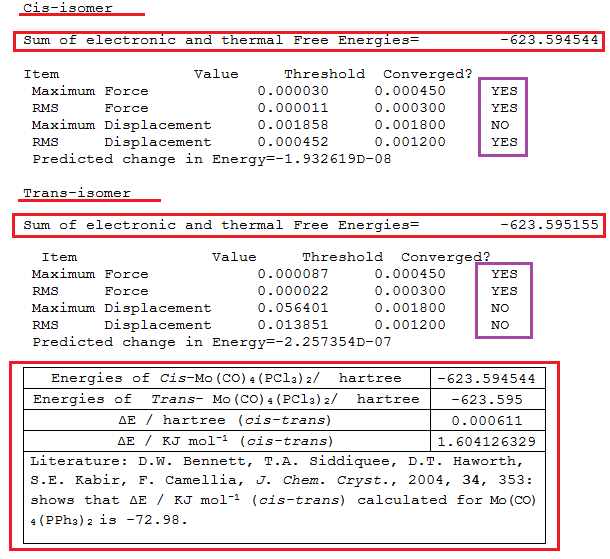

The relative stability of the isomers was rationalised from their energies as displayed below;

First the structures are not minima, as some of the forces did not converge, hence the discrepancy in the point group. The energy difference shows that the trans-isomer is more stable than the cis-isomer by 1.6 kJmol-1 In the yr 2 experiment, thermal isomerisation of the cis-isomer to the trans-isomer was performed and the conclusion was that the thermal isomerisation resulted in the formation of the more stable thermodynamic trans-product, the cis-isomer was a kinetic product of the reaction leading to the formation of the Mo-complex. Enhanced steric interaction was responsible for the cis-isomer being less stable. The isomerisation was deduced to proceed via the lowest energy, non-bond-breaking (Mo-P) process (despite the large cone angles) via a trigonal prismatic intermediate in the Bailar twist or via the C2v intermediate in the Ray-Dutt twist. Thereofore experimental result favour the trans-isomer as the more stable product. However the reference in the table above reports that the cis-isomer is more stable than the trans-isomer by -72.98 kJmol-1!

The literature reported the formation of the trans-isomer in their reaction, but also a cis-isomer had been reported in another reaction. The trans-isomer had C1 symmetry (as observed in this report). Formally, it was suggested that there is a "relatively soft potential surface [between the isomer]" and the fact that a reaction affords a particular isomer depended on external factors rather than molecular parameters" i.e. not due to steric effects as suggested above. Computational analysis by this author provided the conclusion that electronic effect are more influential than the steric effects, and that these electronic effects are responsible for the stability of the cis-isomer. Further suggestions were made that the experimental formation of the trans-isomers were due to "external factors". The rigorous optimisation technique described in this literature afforded a better structure to work with.

7. Mini-project: A study of Sulfur-Nitrogen compounds and analogues (chalcogen-nitrogen compounds)

Health Warning: The following analyses are presented in a logical sequence, so what was asserted in an earlier discourse might be refuted when experimental/computational evidence are discussed.

Aim: This study will investigate the stability of S-N compounds. It will determine the bond lengths and bond angles and the structure of these compounds. The molecular orbitals will be computed and bonding schemes will be explored, particularly the so-called transannular interactions. The study starts with tetrasulfur tetranitride, S4N4, then all the sulfur atoms are substituted for selenium to form tetraselenium tetranitride, Se4N4. A di-substituted analogue, 1,5-Se2S2N4 is also considered. Finally 1,5-O2S2N4 will be studied. Thus by exchanging the other chalcogens for sulfur, the effect of larger or smaller atom (larger, more diffuse orbitals or small) on structure, bonding and stability will be examined.

7.1. Introduction

Tetrasulfur tetranitride, S4N4 was discovered in 1835 (10 years after benzene!) by W. Gregory.[8] Since its discovery it has been subjected to scrupulous analyses (notably by Becke-Goehring and co-workers in the 1950's), both experimentally and via computation. In all these it has shown its worthiness as one of the many gems of inorganic chemistry.

There is considerable amount of interest in S4N4 compounds. It is a useful starting material for several cyclic S-N compounds, these compounds include planar aromatic species. For example S2N2 has 6 electrons. Electron book-keeping is as follows; S has six valence electrons and N has five valence electrons in a planar ring system. If each atom contributes a single electron to the bonds and two electrons are lone pairs then two electron on sulphur and one electron on nitrogen are the ring electrons, therefore in S2N2 there are 6 electrons. It's quite interesting to note that the extra lone pairs mean that the anti-bonding * levels are occupied. The relative stability observed is therefore due to high electronegativity of nitrogen, this lowers the energy of the anti-bonding * orbitals (Klopman-Salem equation, lower nitrogen AO, smaller splitting energy), also long S-N bond lengths reduce electron repulsion.

[9] These S2N2 species polymerise into golden/bronze anisotropic semiconductor with superconducting abilities below 0.33K.[10]

7.2. Structure of Chalcogen-Nitrogen compounds

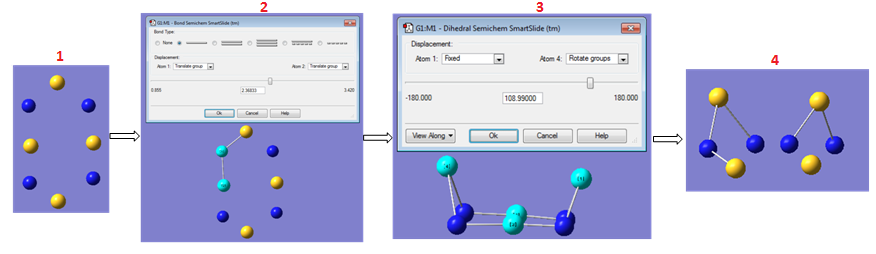

The basic structure of S4N4 is a highly symmetric cage structure with D2d symmetry.[11] Structural study started with the construction of S4N4. The detail of the construction is shown below;

First a framework was constructed as shown in 1, then the bonds were joined, 2. The next step was to distort the planarity of the ring by adjusting the S-S-S-S dihedral angles, 3. Then the middle sulfur atoms were removed and re-introduced at an angle below the N-N-N-N plane, 4. Much instruction was received from ref. 11 regarding the structure of this compound and was the guiding light in the construction of this preliminary structure.

At this point an attempt was made to restrict the geometry of the structure, but the highest symmetry available was C2v, for this reason, a clean-up of the structure was performed.

The next step was to clean up the preliminary structure, again ref. 11 proved useful as it supplied the necessary bond lengths and bond angles. It is important to note that if the information had been unavailable, then an experimentally determined structure would have been sought as a guide, and in the absence of any structural information, a preliminary structural optimisation would have been performed then a clean-up, followed by a second optimisation. The bond lengths of the rough structure were changed from 269pm to 163pm (equal bond lengths), the N-S-N bond angle from 124o to 104.5o and the S-N-S bond angles from 126o to 113o.

The next step was to restrict the point group of the preliminary structure to D2d symmetry (set constraint to awfully loose→choose D2d→symmetrize→choose D2d from point group→set constraint to very tight→OK). After this an optimisation was performed with the keyword, # opt rb3lyp/6-311g(d) geom=connectivity. r denotes restricted (i.e. paired electrons). (d) invokes the d-type functions. The optimised geometry retained the D2d symmetry!

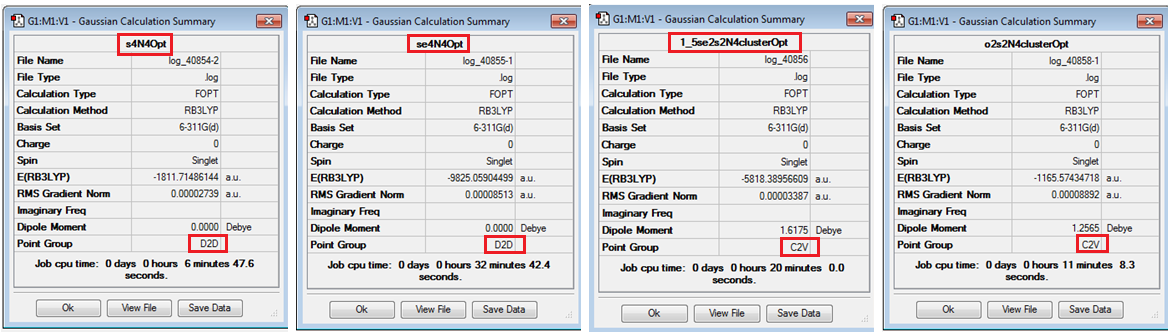

Similar procedure was performed for Se4N4, 1,5-Se2S2N4 and 1,5-O2S2N4. Se4N4 was restricted to D2d point group and the optimised structure retained this symmetry. 1,5-Se2S2N4 was restricted to C2v point group and the optimised structure retained this symmetry, and finally 1,5-O2S2N4 was restricted to C2v point group and the optimised structure retained this symmetry. The results are displayed below;

| S4N4 | Se4N4 | 1,5-Se2S2N4 | 1,5-O2S2N4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOI:10042/to-7679 | DOI:10042/to-7680 | DOI:10042/to-7681 | DOI:10042/to-7682 |

| S4N4 | Se4N4 | 1,5-Se2S2N4 | 1,5-O2S2N4 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

This confirms that correct symmetry was retained after optimisation. In the following analysis literature values refer to ref. 8, 11, values are quoted as (experimental values, ref. 11 (discrepancy); computed values, ref. 8 (discrepancy), see method employed below). For S4N4, the S-N bond lengths/nm agree well with literature values (0.163 (0.6%), 0.163 (0.6%), all S-N bond lengths are all equivalent. The N-S-N bond angles/o agree with literature values (104.5 (3%), 106.6 (0.6%)). The S-N-S bond angles/o agree with literature values (113 (3.5%), 115 (1.7%)). The S-S transannular bond lengths are as follows; (0.260 (10%), 0.275 (4%)), here there is a noticeable deviation from experimetal value. The recorded transannular bond lengths are higher than both literature values. The computed (ref. 8) is also higher than the experimental value. Pritchina et al[8] performed their computational analysis with the B3LYP DFT method using the Dunning's correlation-consistent triple- basis set (cc-pVTZ), a high quality more descriptive method since they can be designed to converge to complete basis set limit. In this study a 6-311g(d)basis set was used, this is a split-valence triple- basis set, a good but relativity less accurate technique, hence the discrepancy in the bond length. Nevertheless obtained value of 0.287nm is still smaller than the sum of the van der Waals radii (0.330nm) and longer than the S-S bond distances of 0.205nm. Therefore there must an attractive interaction between the transannular sulfur atoms.

For Se4N4, the Se-N bond lengths are longer (and they agree with lit. values of 0.180nm), therefore the both N-Se-N and Se-N-Se bond angles are shorter (less electron-electron repulsion). It will be shown later that since selenium has more diffuse orbitals, it follows that the interaction with N(AO) should result in weaker, longer bonds. The Se-Se transannular bond lengths are longer than in S-S, ref. 8 values are 0.276nm (6% discrepancy). It can therefore be suggested that this weaker interaction will result in a less stable compound.

For 1,5-Se2S2N4, the S-N bond length is similar to those in S4N4 (same for the Se-N bond lengths when compared to Se4N4). The N-S-N bond angles are also similar. The Se-N-S bond angles are smaller than the S-N-S angle but larger than the Se-N-Se bond angles, therefore electronic repulsion is strongest in S-N-S interactions, followed by Se-N-S then Se-N-Se i.e. 3(s,p,..)-3(s,p,..) interactions > 3(s,p,..)-4(s,p,..) interactions > 4(s,p,..)-4(s,p,..) interactions. Strangely enough, the Se-Se transannular bond lengths are smaller than in Se4N4 and the S-S transannular bond lengths are longer than any transannular bond length previously discussed. The MO diagram will be scrutinized later for an explanation.

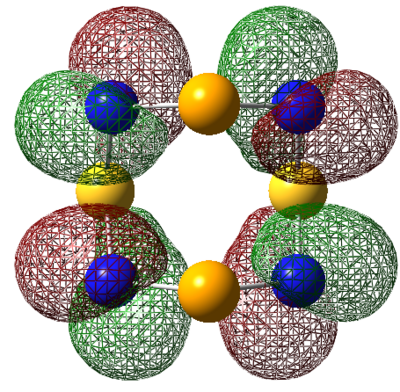

For 1,5-O2S2N4, the S-N bond lengths are shorter compared to the other S-N bond lengths that have been reported. The N-O bond lengths are the shortest of all the bond lengths. The bond angles are at the two extremes of reported values. The S-S transannular bond length is longer than the sum of the van der Waals radii, therefore no transannular interaction exists. The O-O transannular bond length is the shorter of all of such interaction, so this interaction is the strongest. All of the unexplained observations will be rationalised from the molecular orbitals. Note that there is experimental error and also error associated with the computation.

7.3. Molecular orbital and NBO analysis of Chalcogen-Nitrogen compounds

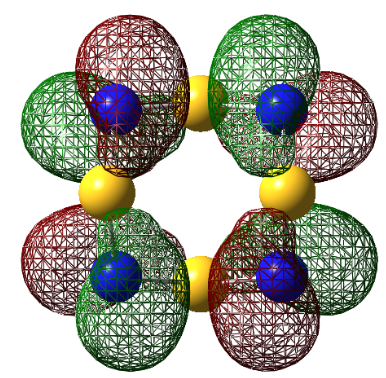

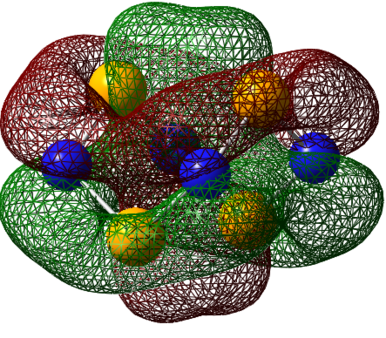

It is interesting to point out the fact that S4N4 can theoretically adopt a number of structures. The first is a planar structure (D4h). The electrons are higher in energy a distortion of this structure lowers the energy of the compound. The transannular interaction of the 3p orbitals is the decisive factor for the preference of the cage-structure over the crown structure. The MO's were computed with # rb3lyp/6-311g(d) pop=(nbo,full) geom=connectivity keyword.

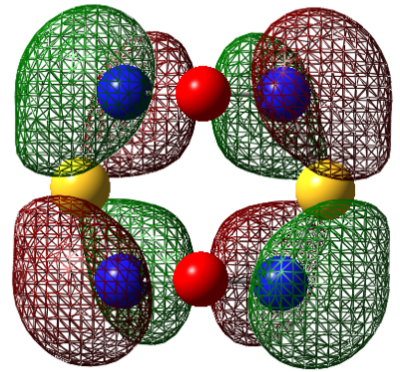

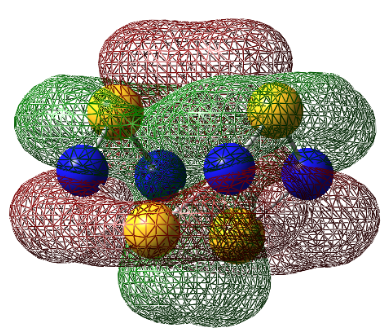

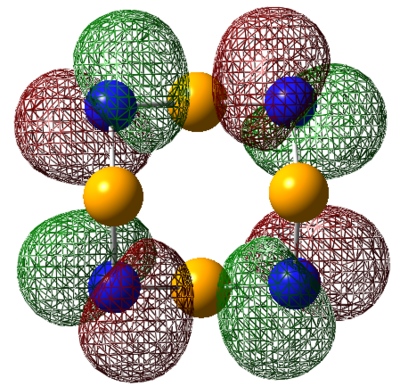

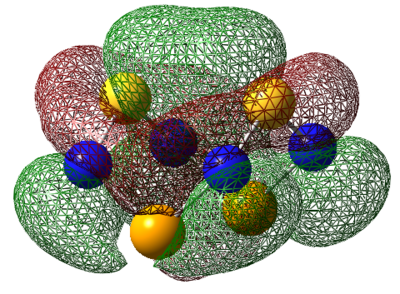

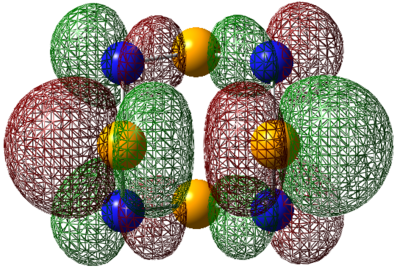

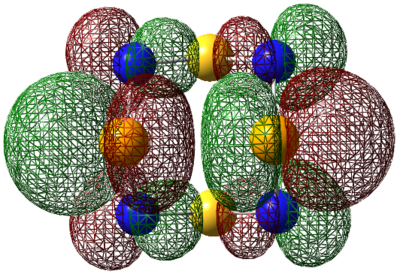

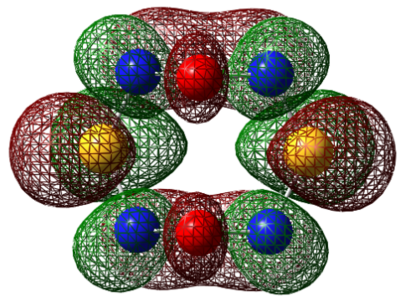

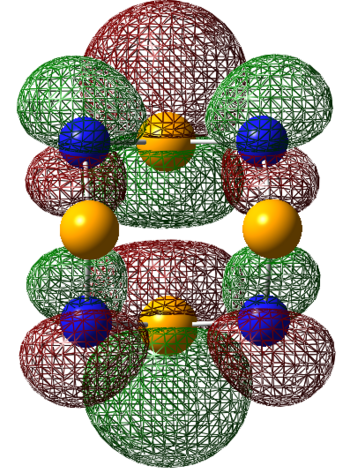

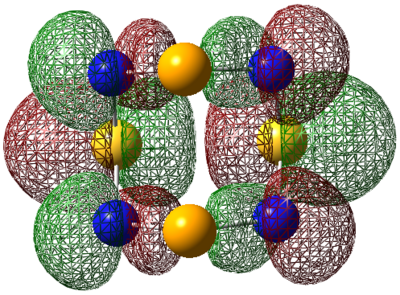

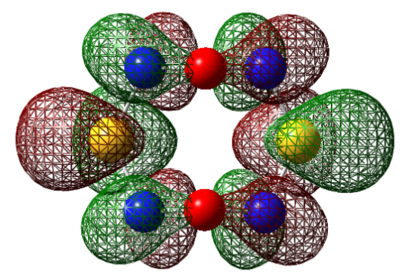

| S4N4 | Se4N4 | 1,5-Se2S2N4 | 1,5-O2S2N4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOI:10042/to-7891 | DOI:10042/to-7892 | DOI:10042/to-7893 | DOI:10042/to-7894 |

| S4N4 | Se4N4 | 1,5-Se2S2N4 | 1,5-O2S2N4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HOMO-1 |

|

|

|

|

| HOMO |  |

|

|

|

| LUMO |  |

|

|

|

| LUMO+1 |  |

|

|

|

| NBO charge |

|

|

|

For S4N4, the MO's appear as expected, there is transannular bonding interaction between the sulfur atom in the HOMO and antibonding interactions in the LUMO. The NBO charge reveals that the nitrogen atoms have high negative charges and and sulphur has high positive charge, the same is observed for the next two compounds. Contrary to the assertion made above, the MO of 1,5-O2S2N4 shows no transannular interaction, there is electron delocalisation over N-O-N, these atoms are electronegative. But any conclusions are made the energies from the frequency calculation will be analysed.

7.4. Infrared spectrum of Chalcogen-Nitrogen compounds

This was computed with the # freq rb3lyp/6-311g(d) geom=connectivity pop=(full,nbo) keyword.

| S4N4 | Se4N4 | 1,5-Se2S2N4 | 1,5-O2S2N4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOI:10042/to-7911 | DOI:10042/to-7912 | DOI:10042/to-7913 | DOI:10042/to-7914 |

| S4N4 | Se4N4 | 1,5-Se2S2N4 | 1,5-O2S2N4 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

A Se-Se bond appears in 1,5-Se2S2N4, this was not drawn in, nor was it present when the vibrations were opened with GaussView. The vibrational modes agree with point group. The '.log file' showed that optimisation was successful, and that stationary points were found and all forces converged. The summary file in the 'optimised structure' gives the total energy of the compounds, these energies are the sum of electronic and thermal free energies. With all these, I make the following conclusions.

7.5. Summary

1. All the compounds show transannular interactions except 1,5-O2S2N4 where electrons are delocalised between N-O-N.

2. The total energy shows that Se4N4 is most stable then 1,5-Se2S2N4 then S4N4 and finally 1,5-O2S2N4.

3. Since the main source of stabilisation is transannular interaction, I can deduce that the Se....Se transannular interaction in stronger than the S....S transannular interaction. For this reason Se4N4 with two Se....Se transannular interaction is most stable followed by 1,5-Se2S2N4 with one Se....Se transannular interaction and S....S transannular interaction then S4N4 with two S....S transannular interaction and finally 1,5-O2S2N4 with no transannular interactions, here the sulfur atoms are too far apart to interact.

4. This conclusion contradicts an earlier statement that Se....Se transannular interactions would be weaker than S....S transannular interactions due to overlap of larger orbitals in selenium i.e. the chemist's reasoning that 2p-2p > 2p-3p > 3p-3p is fulfilled. However ref. 9 reports that for bond lengths between 0.2-0.28nm (within the range and perhaps up to 0.30nm), 3p-3p overlap are greater than 2p-2p overlap. This is reasonable because in the computed MO's, there is no significant 2p-2p overlap between the nitrogen atoms.

5. The observation is exciting indeed! A reversal of well-known interaction strengths!

6. Ref. 10 supports the observation. It provides the stretching force constant (f)/ Nm-1 for transannular bonds which are proportional to 'bond' strength. In Se4N4, f(Se....Se) is 76; In S4N4, f(S....S) is 21; In 1,5-Se2S2N4, f(Se....Se) is 78 and f(S....S) are 36. These data explain the observed trend. One curious observation is that f(S....S) is higher in 1,5-Se2S2N4 than in S4N4. The reason for this might be the NBO charges on the sulfur atoms.

7. Finally, despite longer transannular bond lengths, this interaction is stronger in Se...Se than in S....S.

8. Second order perturbation energy/ (kcal/mol) between the filled orbitals on N due to lone pair and the transannular M...M orbital (M= S, Se) were as high as 31 for S4N4 and 18 for Se4N4. This interaction energy was 33 for Se...Se orbital in 1,5-Se2S2N4 and 16 for the S...S orbitals. For 1,5-Osub>2S2N4, the perturbation energy due to N lone pair-S-N orbital interaction. There are pertubations due to transannular interactions as expected. All these observations are seen qualitatively from the MO diagrams.

9. Also there is antibonding transannular interaction in the HOMO of 1,5-Osub>2S2N4.

Note:Sadly, time constraints did not allow for a more rigorous analysis of this rich data, particularly the NBO data. Further analysis was performed for 1,3-Se2S2N4 to examine Se-S transannular interactions, but I ran out if time and could not analyse this data. The links are as follows (opt; MO/NBO; freq): (DOI:10042/to-7922 ; DOI:10042/to-7923 ; DOI:10042/to-7919 ).

8. Conclusion

Computational analysis is indispensable in the age of precise thinking and experimentation.

9. References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 D.A. McQuarrie, Quantum Mechanics, Oxford University Press, 1983.

- ↑ P. Atkins, J. de Paula, Atkins' Physical Chemistry, 8th Ed., Oxford University Press, 2006.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 G.H. Grant, W.G. Richards, Computational Chemistry, Oxford University Press, 1995.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 C.E. Housecroft, Boranes and Metalloboranes: structure, bonding and reactivity, Ellis Horwood, Chichester, 1990.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 URL; NBO analysis: http://www.chem.wisc.edu/~nbo5/tutorial.html.

- ↑ P. Hunt, Inorganic Symmetry and Spectroscopy, 2011. http://www.huntresearchgroup.org.uk/teaching/year3_symmetry.html

- ↑ K. Kawagichi, J.E. Butler, C. Yamada, S.H. Bauer, T. Minowa, H. Kanamori, E. Hirota, J. Chem. Phys., 1987, 87, 2438.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 E.A. Pritchina, N.P. Gritsan, A.V. Zibarev, T. Bally, Inorg. Chem., 2009, 48, 4075.

- ↑ R. Gleiter, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl., 1981, 20, 444

- ↑ A. Maaninen, R.S. Laitinen, T. Chivers, T.A. Pakkanen, Inorg. Chem., 1999, 38, 3450.

- ↑ C.E. Housecroft, A.G. Sharpe, Inorganic Chemistry, 3rd Ed., Prentice Hall, 2008, pp. 526-528.