Rep:Mod:noyjitat

Computational inorganic chemistry

BCl3

A molecule of BCl3 was optimised using the B3LYP/3-21G method with the following results:

| Bond distance - 1.87 A |

| Bond angle - 120.0 |

| File type - .log |

| Calculation type - FOPT |

| Calculation method - RB3LYP |

| Basis set - LANL2MB |

| Final energy - -69.439 a.u. |

| Dipole moment - 0.00 Deby |

| Point group - D3H |

| Calculation time - 11.0 seconds |

BF3

This was repeated for BF3 with the following results:

Atomic positions (Angstroms)

| Centre Number | Atomic Type | X Coordinate | Y Coordinate | Z Coordinate |

| 1 | C | "0.000" | "0.000" | "0.000" |

| 2 | F | "0.000" | "1.334" | "0.000" |

| 3 | F | "1.155" | "-0.667" | "0.000" |

| 4 | F | "-1.155" | "-0.667" | "0.000" |

| Bond distance - 1.33 A |

| Bond angle - 120.0 |

| File type - .log |

| Calculation type - FOPT |

| Calculation method - RB3LYP |

| Basis set - LANL2MB |

| Final energy - -319.872 a.u. |

| Dipole moment - 0.00 Deby |

| Point group - D3H |

| Calculation time - 18.0 seconds |

Upload log file

BH3 vibrational analysis

BH3 was optimised in the same manner as above and the vibrations were then calculated:

Giving the followng IR spectrum

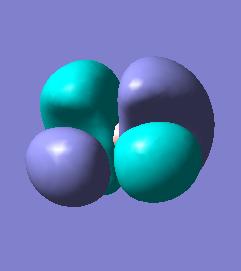

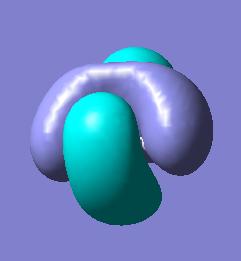

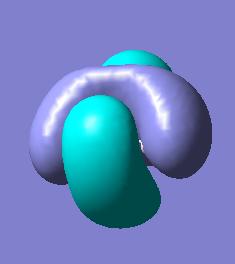

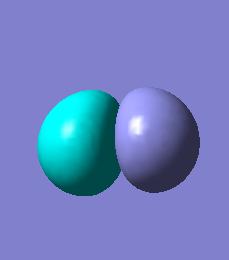

BH3 molecular orbitals

The molecular orbitals for BH3 can now be calculated by the same method as above and compared to the qualitative MO diagram.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

There is good agreement between the occupied qualitative MOs and the occupied quantatative calculated MOs. The shapes are reasonable when compared to the linear combination of orbitals and the predicted degeneracies hold. The unoccupied orbitals however, show little agreement. The predicted LUMO for BH3 is a simple Pz orbital on the boron whereas the calculated LUMO is far more complex and presents a different symmetry making the predicted LUMO a very bad model. The quantative LUMO+1 and LUMO+2 levels are also given as degenerate, differing again from prediction.

NH3

Three versions of the NH3 molecule restrained to different symmetries were optimised using a 6-31G basis set and the B3LYP method. Summeries of these optisations are given below

By changing the symmetry we change the structure of the optimised molecule in terms of both bond lengths and angles.

Time needed to optimise the geometry increaced with increacing degree of symmetry. This is due to the fact that the molecule cannot break symmetry at any stage of the optimization and so each step must be calculated to conform to the correct symmetry. This takes more time for a higher symmetry since it contains more symmetry elements which must be calculated. This indicates that calculations on molecules with very high symmetry (for example Oh) would be very time consuming indeed.

The lowest energy geometry was the C1 geometry, with the energy differences between the diffrent geometries given above. These differences represent the energy barrier to movement between differering geometries. This barrier is clearly small.

The C3V and D3H calculations were then repeated from scratch using the higher level MP2/6-311+G(d,p) method and basis set. These calculations took 33.0 sec and 1 min 35.0 sec respectively, an increace of around 20% on the calulation time for the B3LYP/6-31G calculation. The energy has also been reduced in the order of 0.1 a.u. giving an energy difference between D3H and C3V symmetries of 20.5 kJ/mol. Since the D3H symmetry represents the trasition state for inversion of ammonia this figure represents the barrier height to inversion and is in reasonable agreement with the experimental value of 24.3 kJ/mol.

NH3 vibrational analysis

The vibrations for NH3 were then calculated from the B3LYP/6-31G optimised structures of C3v and D3h symmetry. The IR spectra are seen here.

| Calculated frequency (D3h)/cm-1 | Calculated frequency (C3v)/cm-1 | Experimental frequency/cm-1 [1] |

| 452 | "-318" | 950 |

| 1680 | 1641 | 1627 |

| 1680 | 1641 | 1627 |

| 3575 | 3636 | 3336 |

| 3776 | 3854 | 3414 |

| 3776 | 3854 | 3414 |

These results show the C3v structure to be the ground state since it has all positive frequencies. The D3h structure has a sigle negative frequency at -318 which shows it to be a transition state. The vibration at this frequency is the a'2 "umberella" like stretch and this is the vibration which follows the inversion reaction path.

Cis-Trans isomerism of [Mo(CO)4(pip)2]

Models of both the cis and trans forms of [Mo(CO)4(pip)2] (pip = NC5H10) were optimised initially to a loose convergence using the B3LYP/LANL2MB method and basis set and then to a increased convergence using the more accurate B3LYP/LANL2DZ method and basis set.

Cis-[Mo(CO)4(pip)2] DOI:10042/to-1972

Cis complex |

Trans-[Mo(CO)4(pip)2] DOI:10042/to-1974

Trans complex |

The first obvious difference in the geometry of the two complexes is that the Trans complex is very close to perfect octohedral geometry at the Mo centre with a varience from the expected bond angles of 90 degrees of only 4 degrees in C-Mo-C and less than 1 degree in C-Mo-N. The trans complex also has equal Mo-L bond lengths of 2.06 angstroms for all ligands, both CO and pip. In the Cis complex however the steric bulk of the ligands has forced a large distortion in the expected octohedral geometry with an N-Mo-N bond angle of 110 degrees. Bond lengths are also no longer equal with the majority of the bonds shortened to ~2.05 angstroms and the Mo-C bonds Trans to the piperidine ligands lengthened to 2.08 and 2.09 angstroms. Mo-N bond lengths typically range between 2.45 and 2.06 angstroms [2] placing both complexs at the extreme lower end of the range and suggesting double bond character. The Trans complex is the more thermodynamically favoured due to the strain described with an energy difference between conformations of 0.00194 a.u. (5.11 kJ/mol). This could be altered by substituting less bulky ligands or by linking the piperidine ligands to create a single bidentate ligand.

Vibrational analysis of [Mo(CO)4(pip)2]

Vibrations of [Mo(CO)4(pip)2] were then calculated from the previous models for both Cis DOI:10042/to-1976 and Trans DOI:10042/to-1977 forms of the complex producing the predicted spectra shown here.

Mini Project

Dimerisation of the ruthenocenium ion

J.C. Swarts et. al. [1] observed that upon electrochemical oxidation of ruthenocene, [RuCp2], to Ruthenocenium, [RuCp2]+, the resultant complex tended to dimerize to a Ru-Ru linked dication 2 which converted reversibly with loss of dihydrogen to a Ru-Cp linked dication 3 upon heating.

In this mini project this thermal equilibrium will be investigated. Firstly to see if dication 3 is intrinsically thermodynamically favoured when the effects of solvent and coordinating anion are removed and secondly to see what effect changing the sustituents on the Cp rings has upon the position of the equilibrium.

All calculations use the B3LYP/LANL2MB method and basis set as the LANL2MB basis set, although more accurate, was thought too computationally demanding for a molecule of this size.

The unsubstituted dimers were calculated first with the following results:

| 2 | 3 | ||||

| DOI:10042/to-1996 | DOI:10042/to-1999 |

The energy difference between the two complexes is 2034 kJ/mol. Although it is to be expected that the figure in solution would be altered this demonstrates that dication 3 is intrinsically much more stable than cation 2 which is supported experimentally by the rapid conversion of 2 to 3 once heated above the temperature of 243K at which it is synthesised.

This energy difference can be either increaced or reversed, so that the Ru-Ru linked dimer is thermodynamically prefered, by tuning the ring substituents. When analogus structures where the hydrogens of the Cp rings are replaced by highly electron withdrawing fluorines were calculated the results were as follows:

| [Ru2(η5C5F5)4]2+ (analogous to 2) | [Ru2(η5C5F5)2(σ:η5C5F4)2]2+ (analogous to 3) | ||||

| DOI:10042/to-1998 | DOI:10042/to-1994 |

These complexes proved so high in energy compared to the initial complexes (the energy difference between the H-substituted and F-substituted Ru-Ru complexes is 5.67*107 kJ/mol) that it is highly unlikely they could be synthesised in reality. However they demonstrate the theoretical influence of electron withdrawing substituents which is indicative of the influence that fewer or less electron withdrawing substituents would have. As for the origional complex the Ru-Ru linked dimer is thermodynamically more stable with the energy difference between conformations being huge at 516000 kJ/mol. Electron withdrawing substituents on the rings will therefore tend to push the equilibrium further towards the Ru-Cp linked dimers.

When analogus structures where one hydrogen of the Cp rings is replaced by a bulky isopropyl group were calculated the results were as follows:

| [Ru2(η5C5H4iPr)4]2+ (analogous to 2) | [Ru2(η5C5H4iPr)2(σ:η5C5H3iPr)2]2+ (analogous to 3) | ||||

| DOI:10042/to-1997 | DOI:10042/to-1995 |

These complexes proved much more stable than the F-substitued complexes, although still significantly less so than the origional complexes with an energy difference of 1.22*107 and may still be too unstable to synthesise in reality. In this case the preference is reversed with the Ru-Ru linked dimer becoming more stable with an energy differency between conformations of 4122 kJ/mol.

It has been demonstrated therefore that this equilibrium may be tuned towards a Ru-Ru or Ru-Cp linked dimer by adustment of the ring substituents with electronegative substituents being required to push the equilibrium towards Ru-Ru linking and bulky substituents being required to push the equilibrium towards Ru-Cp linking.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 <a href=http://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/ic802105b>J.C. Swarts et. al., Inorg. Chem., Article ASAP, DOI: 10.1021/ic802105b, Publication Date (Web): January 26, 2009</a>