Rep:Mod:nightfox

Molecular Mechanics Modelling

Introduction

Molecular mechanics (MM) provides a method to calculate the energy and properties of molecules. It involves optimising the molecular geometry to an energy minimum and finding the final energy in terms of bond length and angle strain, steric effects and van der Waals contributions. The technique avoids calculating the exact energy based on the Schrodinger equation and run in short amount of time. Molecular mechanics models the energy of molecules by calculating five independent terms that describe the individual bond properties. These are;

The sum of all diatomic bond stretches (approximated with the Hookes law potential)

The sum of all triatomic bond angle deformations (calculated using a Hookes law potential)

The sum of all tetra-atomic bond torsions (cosine dependence on dihedral angle)

The sum of all non-bonded Van der Waals attractions and repulsions (approximated using the Lennard-Jones 6-12 potential)

The sum of all electrostatic attractions of individual bond dipoles

The functions are easy to solve using experimentally derived parameters. However, as the constraints are experimentally derived and the equations used are based on simple diatomic. The method is limited to simple molecules and starts to break down when modelling non-classical systems or aromatic systems. In this experiment, both the Allinger[1] MM2 and MMFF94 programs were used.

Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

Dimerisation of Cyclopentadiene

At room temperature, Cyclopentadiene dimerises to produce specifically the endo dimer 2 rather than the exo dimer 1 via Diels Alder mechanism.

The stereospecficity of this reaction can be investigated by comparing the relative energies of dimers 1 and 2, these energies were obtained using geometry optimisation with MM2 force field on ChemBio3D-12.0.

| Energies/ kcal mol-1 | Energies/ kJ mol-1 | |||||||||||

| Stretch | Bend | Torsion | Van der Waals | Dipole-Dipole | Total | Stretch | Bend | Torsion | Van der Waals | Dipole-Dipole | Total | |

| exo dimer 1 | 1.28 | 20.59 | 7.65 | 4.24 | 0.38 | 31.88 | 5.36 | 86.15 | 32.00 | 17.74 | 1.59 | 133.38 |

| endo dimer 2 | 1.26 | 20.85 | 9.51 | 4.30 | 0.45 | 34.00 | 5.27 | 87.24 | 39.79 | 18.00 | 1.88 | 142.26 |

Table 1: Relative Energies of exo dimer 1 and endo dimer 2

The total energy of the two dimers show the exo dimer 1(133.38kJ/mol) is 8.88kJ/mol more stable compared to the endo dimer 2(142.26kJ/mol). This indicates the exo dimer is the thermodynamically favourable product of the dimerization reaction, this is confirmed by literature findings[2]. However the reaction produces specifically the endo dimer, the formation of the less thermodynamically favourable product is due to the reaction being under kinetic control. The kinetic product dominates since the Diels Alder reaction is irreversible and the reaction takes place at low temperatures. The formation of the endo dimer(kinetically favourable product) proceeds via a lower energy transition state as a stabilising “secondary orbital interaction” is possible. This endo-selectivity is confirmed by selection rule derived by Woodward-Hoffman[3], and Alder's endo-rule[4].

Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

Upon partial hydrogenation of the endo dimer 2, two different dihydro derivatives 3 or 4 could be formed depending which on which C=C double bond is hydrogenated. The tetrahydro derivative is only formed after prolonged hydrogenation.

The total energy and the relative contributions from the stretching, bending,torsion, van der Waals and hydrogen bonding energy were found.

| Energies/ kcal mol-1 | Energies/ kJ mol-1 | |||||||||||

| Stretch | Bend | Torsion | Van der Waals | Dipole-Dipole | Total | Stretch | Bend | Torsion | Van der Waals | Dipole-Dipole | Total | |

| dihydro derivatives 3 | 1.27 | 19.80 | 10.87 | 5.64 | 0.16 | 35.70 | 5.31 | 82.84 | 45.48 | 23.60 | 0.67 | 149.37 |

| dihydro derivatives 4 | 1.10 | 14.53 | 12.51 | 4.50 | 0.14 | 31.16 | 4.60 | 60.79 | 52.34 | 18.83 | 0.59 | 130.37 |

Table 2: Relative Energies of dihydro derivatives 3 and 4

The total energy of product 4(130.37kJ/mol)is 19.0kJ/mol lower than product3, therefore product 4 is the thermodynamically favourable product. This indicates the C=C double in the 6-membered ring is more readily hydrogenated compared to that in the 5 membered ring. This is indeed observed in literature, where product 4 is formed from partial hydrogenation of endo-dicylopentadiene before formation of the tetrahydro derivative after prolonged hydrogenation.

The main factor differentiating the energies of the hydrogenated compounds is the bending energy contributions. Bending strain relates specifically to the deviation from ideal bond angle. The bending strain in product 3 is 22.05 kJ/mol larger than product 4. In product 3 the double bond is in the five membered ring, the bicyclic unit is highly strained because the deviation of the C=C bond angle (~108°) from its ideal sp2 bond angle of 120°is large. Whereas in product 4 the double bond is in the six membered ring with bond angle ~113° which is closer to the ideal angle(small bending strain) , moreover the strain in the five membered ring is reduced. Hence product 3 has a higher bending energy and lower stability.

Stereochemistry of Nucleophilic additions to a pyridinium ring

N-Methyl Pyridoxazepinone with Grignard Reagent

The nucleophilic addition of Grinard reagent methyl magnesium iodide to the optically active N-methyl pyridoxazepinone 5 results in alkylation of the pyridine ring in the C4 position, with absolute stereochemistry shown in product 6[5].

The regio-selectivity of the reaction can be understood through the interaction of the O atom of the amide group with the Mg of the Grinard reagent, Shultz et al[6] postulated that the electropositive Mg of the incoming Grinard reagent coordinates to the electronegative carbonyl oxygen. This Mg to O coordination spatially directs the nucleophilic Me group to attack the C4 position on the pyridinium ring, illustrated by the transition state structure. The MeMgI component could not be included in the calculations as Magnesium is not a recognised atom type for MM2.

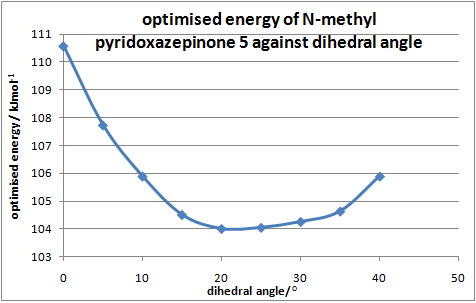

The geometry of the carbonyl group(above or below plane of pyridinium ring) determines whether the nucleophilic Me group attacks the C4(pyridinium ring)from above or below, thus determining the stereo-selectivity of the reaction. The geometrically optimised structure shows the carbonyl is pointing 'up' with respect to the planar pyridinium ring. The geometry of N-methyl pyridoxazepinone 5 was optimised with respect to the dihedral angle between the O atom of the carbonyl group and the C4 position of the pyridinium ring. (calculation performed on ChemBio3D-11.0 due to bug problem with N+ in ChemBio3D-12.0). The optimal angle at which the total energy of 5 is minimal can be found by plotting a graph(Fig.1).

| Dihedral angle/° | Energy/kcalmol-1 | Energy/kJmol-1 |

|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 26.43 | 110.58 |

| 5.0 | 25.75 | 107.74 |

| 10.0 | 25.31 | 105.90 |

| 15.0 | 24.98 | 104.52 |

| 20.0 | 24.86 | 104.01 |

| 25.0 | 24.87 | 104.06 |

| 30.0 | 24.92 | 104.27 |

| 35.0 | 25.01 | 104.64 |

| 40.0 | 25.31 | 105.90 |

Table 3:relative energies and dihedral angles of 5

The minimum energy conformation was found when the dihedral angle is 23.5°, with the carbonyl group pointing above the plane of the ring. Low energy conformation were not found at negative dihedral angles indicating the C=O group does not point below the plane. Therefore the Mg atom of the incoming Grinard reagent coordinates above the plane of ring resulting in nucleophilic addition occurring at the top face of the C4 position in pyridinium. This gives the stereoselectivity observed in product 6.

N-methyl Quinolinium Salt with Aniline

The nucleophilic addition of aniline to N-methyl quinolinium Salt 7 is also regio- and stereo-selecitive.

The PhNH2 nucleophile attacks the C4 position on the pyridinium ring as it is the only position available for addition.

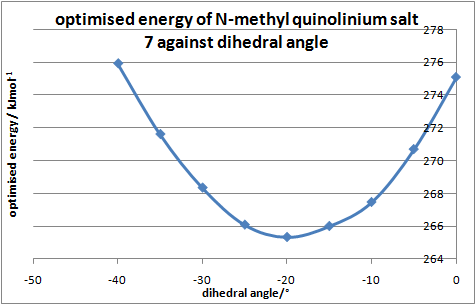

The geometrically optimised structure shows the carbonyl is pointing 'down' with respect to the planar pyridinium ring, the optimal dihedral angle(between the O atom of the carbonyl group and the C4 position of the pyridinium ring) at which the total energy of 7 is minimal was investigated.

| Dihedral angle/° | Energy/kcalmol-1 | Energy/kJmol-1 |

|---|---|---|

| -0.0 | 65.75 | 275.10 |

| -5.0 | 64.70 | 270.70 |

| -10.0 | 63.93 | 267.48 |

| -15.0 | 63.58 | 266.02 |

| -20.0 | 63.42 | 265.35 |

| -25.0 | 63.60 | 266.10 |

| -30.0 | 64.14 | 268.36 |

| -35.0 | 64.92 | 271.63 |

| -40.0 | 65.95 | 275.93 |

Table 4:relative energies and dihedral angles of 7

The stereoselectivity observed is due to the coulombic repulsion between the carbonyl(lone pair on oxygen) and PhNH2(lone pair on nitrogen). The optimal dihedral angle of 20.0° (fig2.) indicates that the C=O bond is pointing below the plane of the ring(Low energy conformation were not found at positive dihedral angles, the C=O group does not point above the plane), hence the nucleophile attacks from above the plane to minimise repulsions resulting in stereochemistry of product 8. This is consistent with findings of Leleu et al[7], which states that the amines react on the opposite face with respect to the C=O bond of the amide group.

Possible Improvements

The problem experienced with Mg atom could be overcome by manually defining the cation parameters and saving it in the MM2 force field. Alternatively, MOPAC(takes into account the molecular orbitals and electronic structure of molecules) or DFT calculations could be used to visualise and predict the energy changes as MeMgI interacts with N-Methy Prodoxazepinone5.

Stereochemistry and Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

The total synthesis of Taxol involves the formation of a key intermediate 9 or 10. Initially both compounds are synthesised with the carbonyl group pointing either up or down, forming altropisomers(stereoisomers in which rotation about singles bonds is hindered by steric strain and prevents interconversion of isomers), the rotation about the single bonds either side of the C=O group is restricted due to the steric strain experienced as C=O rotates. On standing, the atsropisomers were observed to isomerise to a single carbonyl isomer with high alkene stability.

The relative energies of these alropisomers were calculated using the MM2 method to determine the stereochemistry of carbonyl addition(table 5).

| Energies/ kcal mol-1 | Energies/ kJ mol-1 | |||||||||||

| Stretch | Bend | Torsion | Van der Waals | Dipole-Dipole | Total | Stretch | Bend | Torsion | Van der Waals | Dipole-Dipole | Total | |

| intermediate 9 -Chair | 2.67 | 15.82 | 18.21 | 12.64 | 0.15 | 48.89 | 11.27 | 66.19 | 76.19 | 52.88 | 0.64 | 204.56 |

| intermediate 10 -Chair | 2.56 | 10.04 | 19.28 | 12.69 | -0.19 | 43.21 | 10.71 | 42.00 | 80.67 | 53.09 | -0.79 | 180.79 |

Table 5: relative energies of intermediates 9 and 10 (MM2 force-field calculation)

The optimised structures show the most stable conformations were found when both rings in each molecule adopt the chair form(rather than boat). The total energy indicates intermediate 10(180.79 kJ/mol) is more energetically favourable than intermediate 9(204.56 kJ/mol) by 23.77 kJ/mol. The energy contributions indicate atropisomer 10 has significantly lower bending strain than atropisomer 9. Hence, the analysis predicts intermediate 9 will spontaneously isomerise to intermediate 10. Indeed, this was observed by Paquette et al[8].

The energetic stability were analysed using MMFF94(suitable for biological systems). The calculated values were considerably higher(~10kcal/mol) than those found using MM2, but agrees atropisomer10 is more energetically stable than atropisomer9.

| Total Energy of Intermediate | ||||

| MM2/ kcal mol-1 | MM2/ kJ mol-1 | MMFF94/ kcal mol-1 | MMFF94/ kJ mol-1 | |

| Intermediate 9 -Chair | 48.89 | 204.56 | 70.54 | 295.14 |

| Intermediate 10 -Chair | 43.21 | 180.79 | 61.23 | 256.19 |

Table 6: Comparing the total energy calculated using MM2 and MMFF94 force field

Hyperstable Alkenes

The intermediate is an example of a hyperstable alkene due to high stability of the bridgehead alkene. Hyperstable olefins have negative olefin strain energies (OSE) and are less strained than their parent saturated hydrocarbons. OSE is lowered by the increase in number of vicinal and transannular hydrogen van der Waals interactions in the alkene. The hydrogenation of the alkene is disfavoured as the alkane formed would contain very high levels of strain(much higher than the alkene). Moreover, the alkene is sterically hindered to incoming reactants. Therefore, the hyperstable alkene reacts abnormally slowly and is very difficult to hydorgenate.

Modelling Using Semi-empirical Molecular Orbital Theory

In this section, electronic aspects of reactivity such as "secondary orbital" interactions are taken into account to show how the electrons influence bonds and how spectroscopic properties can be derive.

Regioselective Addition of Dichlorocarbene

Orbital Control of Reactivity

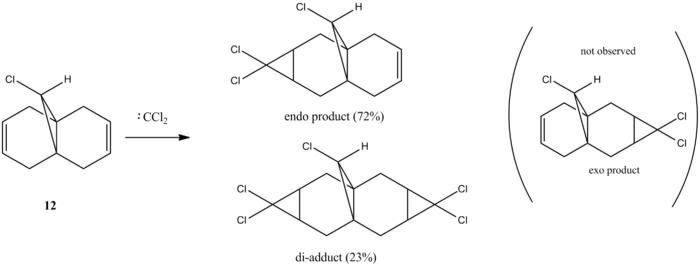

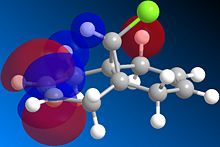

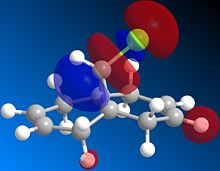

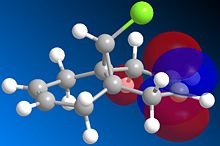

Orbital control of reactivity can be illustrated in the reaction of compound 12 with electrophilic reagents. In the reaction of 9-Chloro-1,4,5,8-tetrahydro-4a,8a-methanoaphthalene 12 with dichlorocarbene, the addition was observed by Halton el al[9] to be highly regioselective. The electrophile adds exclusively across the syn alkene C=C forming the endo product, addition across the anti alkene(forming exo product) was not observed. This control of reactivity can be predicted by computing the energy and shape of the molecular orbitals using MOPAC/PM6(table 7), optimisation with MOPAC/PM6 resulted in a heat of formation of 19.74 kcal/mol.

|

|

|

|

|

Table 7: molecular orbitals and energy levels of compound 12

The HOMO(highest occupied molecular orbital) and LUMO(lowest occupied molecular orbital)controls the reactivity of a compound, therefore they are analysed to predict the regioselectivity of the electrophilic addition.

The HOMO shows there is a much greater degree of electron density at the syn alkene C=C ( C=C bond on the same side as Cl) compared to the anti C=C. Therefore the syn C=C is most nucleohilic due to having the largest proportion of the HOMO located on it and will most readily react with electrophiles resulting in the endo product(72%)[9]. Orbital energies can be found to quantitatively show the difference between the two C=C bonds.

Rzepa et al[10] attributed the lower molecular orbital energy of the anti C=C to the antiperiplanar stabilising interaction between σ*(C-Cl) and π(C=C)orbitals. This is observed in the above figures, the antiperiplanar interaction occurs between the LUMO+1 (σ*(C-Cl)) and the occupied HOMO-1(π(C=C)) resulting in stabilisation of the anti-alkene leading to its lower reactivity (LUMO and LUMO+2 are π* orbitals). In the literature, the PM3 method of MOPAC was used instead of PM6 which may have resulted in the discrepancy in shapes and structure of the molecular orbitals.

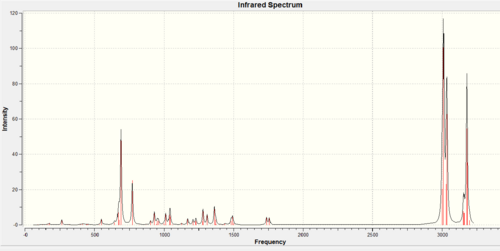

Vibrational Frequencies

The influence of the Cl-C bond on the vibrational frequencies of molecule 12 and its hydrogenated form, the monoalkene 13 can be calculated using B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) Gaussian geometry optimization and frequency calculation.

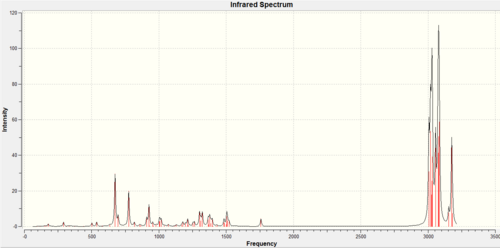

| IR Spectrum |  |

|

| C-Cl/ cm-1 | 770.88 | 774.98 |

| C=C (anti)/ cm-1 | 1737.04 | N.A. |

| C=C (syn)/ cm-1 | 1757.35 | 1758.07 |

Table 8 : Comparison of vibrational frequencies between dialkene 12 and monoalkene13

Data for 12: DOI:/10042/to-6406 Data for 13: DOI:/10042/to-6405

The IR spectra of the two compounds are similar as the same functional groups are present. The main difference is that the dialkene 12

(1737cm-1 (anti) and 1757cm-1 (syn)) have two C=C stretch frequencies whereas only one is observed for the monoalkene 13(1758cm-1 (syn)). The C=C stretching frequencies are higher than typical alkenes (1600-1700cm-1)[11], this is likely due to the electron withdrawing Cl. Moreover, the antiperiplanar stabilisation interaction between σ*(C-Cl) and π(C=C)discussed earlier can lower the energy of the occupied HOMO leading to a more stable and strong bond with higher vibrational frequency. The C-Cl vibrational frequencies (770.88 (dialkene) and 774.98cm (monoalkane)-1) corresponds well with literature value (780cm-1)[11].

For the dialkene 12 compound, the anti C=C (1737cm-1) stretching frequency is lower than the syn C=C(1757cm-1). This can be explained as some of the anti π electrons are withdrawn away from the bond and into the C-Cl region to form the stable chloride anion. The π electron density of the C=C bond decreases as a results and the bond itself becomes more stable and less reactive due to π electrons being less stable than σ. Hence, the anti C=C will stretch more easily(lower stretching frequency) due to having more σ character in the bond.

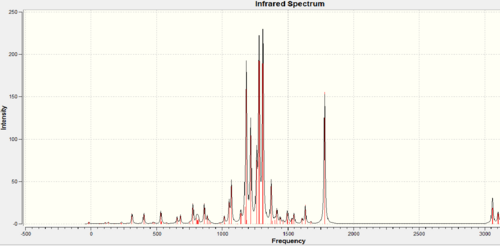

Modifying the substituents

The substituents on the anti/exo alkene are modified from the =C-H group to =C-OH, =C-CN, =C-BH2 and =C-SiH3 groups. The effects of this on the vibrational frequencies of Cl-C and C=C can be analysed (table 9)

| Derivative | C-Cl/ cm-1 | C=C (anti)/ cm-1 | C=C (syn)/ cm-1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| dialkene 12 | 770.88 | 1737.04 | 1757.35 |

| monoalkene 13 | 774.98 | N.A. | 1758.07 |

| =C-OH | 766.82 | 1776.58 | 1756.20 |

| =C-CN | 765.68 | 1706.45 | 1756.56 |

| =C-BH2 | 759.03 | 1657.24 | 1756.54 |

| =C-SiH3 | 763.80 | 1690.34 | 1756.27 |

Table 9 : IR vibrations of various derivatives of molecule 12(cm-1

Data for =C-OH: DOI:/10042/to-6421 Data for =C-CN: DOI:/10042/to-6422 Data for =C-BH2: DOI:/10042/to-6423 Data for C-SiH3: DOI:/10042/to-6453

The results show the C-Cl and syn C=C stretches are not greatly effected by the changes in substituents whereas the anti C=C stretches alter significantly.

The anti alkene is strengthened by the hydroxy group as the O atom donates electron density to the C=C bond via resonance resulting in stabilisation of the bond(higher stretching frequency). In the cyano substituens, the C=C bond is destabilised due to electron density being withdrawn by the electronegative N atom(lower stretching frequency). The largest change in vibrational frequency was observed in the BH2 substituent, BH2 acts as a Lewis acid and accepts electrons from the π C=C bond using its low lying unoccupied p-orbitals, this weakens the alkene bond. This also accounts for the weak bond(lower vibrational frequency) in the silyl substituent, the effect is less significant compared to BH2 as silicon d-orbitals are less good at accepting electron due to having more diffuse orbitals with higher energy.

Structure-Based Mini-Project

Many reactions carried out by synthetic chemists give a mixture of products which are often isomers. The predominant isomer can usually be predicted fairly confidently by understanding the mechanism by which the reaction proceeds. However, it is necessary to conclusively confirm the expected product has been obtained. This is usually carried out through spectroscopic methods( NMR being the most useful) but modern computational chemistry provides an alternative to this and is studied here.

Introduction: Orthogonal Synthesis of Isoindole and Isoquinoline

Isoindoles and their derivatives have high fluorescent and electroluminesent properties, therefore they are good candidates for organic light-emitting devices (OLEDs)[12].

The regioselective reaction reported by Hui et al[13], involves the selective synthesis of Ethyl 3-methyl-2H-isoindole-1-carboxylate 1 and Ethyl isoquinoline-1-carboxylate 2(regioisomers) from a α-azido carbonyl compound possessing 2-alkeneylaryl moiety at the α-position. The regio-selectivity of the reaction is induced by a slight modification of the reaction conditions (shown below).

Mechanistic Analysis

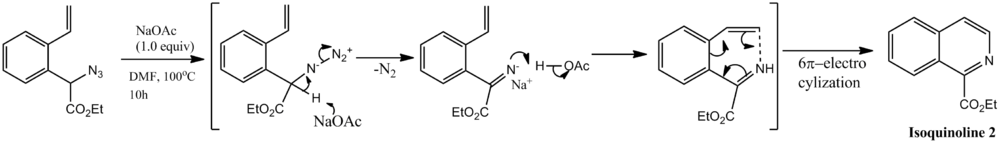

The two products are formed by two different proposed mechanisms. The isoindole is formed via a intramolecular azide-alkene cycloaddition by heating of the azides in the absence of base. The formation of isoquinoline involves a 6 π-electrocyclization in the presence of one equivalent of suitable base[13].

Formation of isoindole - 1,3-dipolar cyloaddition of azide onto alkene followed by elimination of nitrogen:

Formation of isoquinoline - 6π-electrocyclization of N-H imine intermediates( Baldwins rule-allowed, 6-exo-tet ring closure)

Computational analysis

The structures of the two molecules were first optimised using MM2 methond, several conformational possibilities were investigated to find the one with lowest energy. Then the structures were optimised using DFT molecular orbital theory to investigate and predict the 13C NMR, 1H NMR and infrared spectroscopy .

Optimisation with MM2 force field

Both structures are quite rigid leading to small number of possible conformations, this is ideal for energy optimisation. The most stable conformations were found (table 10).

| optimised structure | Total Energy/ kcal mol-1 |

|---|---|

17.9

| |

21.2

|

Table 10: optimisation using MM2 force field

For the Isoindole product, the aromatic rings adopt the planar orientation and the C=O is planar with respect to the ring. This results in stabilisation due to overlap of the π orbitals leading to a conjugating π system. The ester group take up an s-cis conformation, the *σ C=O orbital is antiperiplanar to one of the sp2 oxygen lone pairs resulting in stabilising anomeric interaction. The other oxygen lone pair(in p-orbital) overlaps with the *π C=O orbital.

In the isoquinoline product, the aromatic rings and ester group adopts the planar and s-cis conformation respectively. The major difference to isoindole is that the C=O group is no longer planar with respect to the aromatic rings. This is due to the lone pair on the nitrogen atom in the ring, the low energy structure must minimise the electron repulsions between the lone pair on N and the lone pairs on the two oxygens in the ester group.

The optimised energies indicate the isoindole product is more stable than the isoquinoline product by 3.3kcal/mol. This suggests the thermodynamically favourable product is formed in the absence of base, and the addition of base will induce the kinetic product(isoquinoline) of the reaction. This is consistent with the mechanisms proposed, the formation of isoquinoline avoids the high energy triazoline(highly strained-3 rings)transition state and hence have a lower activation energy.

13C NMR

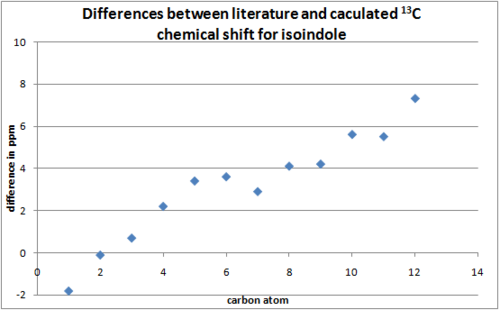

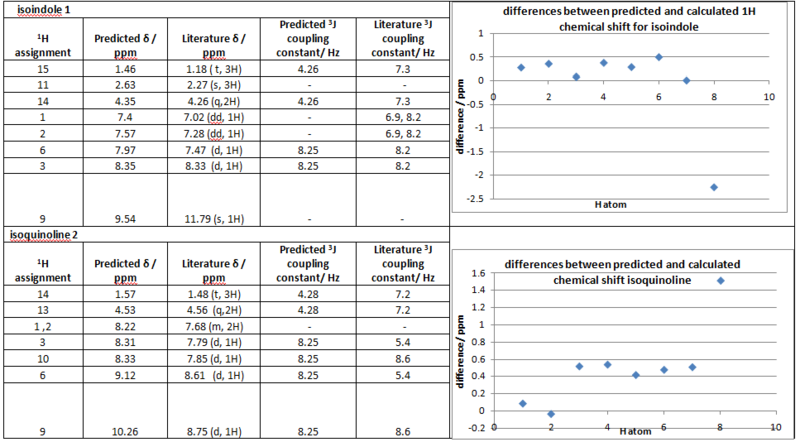

The 13C spectra was predicted using the GIAO method(Gaussian mpw1pw91/6-31(d,p)) for the isomers. The isoindole NMR was predicted in deuterated benzene while the isoquinoline NMR in chloroform to allow comparison with literature[13]. The 13C spectra should be effective in differentiating between the two isomers as spectra produced by the two regioisomers should differ. The difference between predicted and literature[13] shifts were shown in the two graphs, the carbon atoms on the x axis were plotted in order of chemical shifts(lowest to highest).

structures after mpw1pw91/6-31(d,p)optimisation (very similar to that obtained from MM2 optimisation)

Table 11: comparison of 13C NMR between literature and predicted values

NMR data for isoindole: DOI:/10042/to-6454 NMR data for isoquinoline: DOI:/10042/to-6427

The predicted 13C chemical shifts correlate well with that of literature[13]. All the peaks reported in the literature were predicted with reasonable accuracy indicating the structure calculated by the program closely resemble the actual structure synthesised and reported in the literature.

The two isomers can be differentiated by the C-11 peak of the isoindole product. This alky(-CH3) carbon appears at low ppm(15.2ppm) as it is not deshielded by the ring current. Whereas the same carbon atom(labelled as C-9) in the isoquioline is part of the aromatic ring and is highly deshielded(138.7ppm).

From the graphs plotted, it can be observed that the shifts predicted for the isoquinoline product corresponds better with the literature compared to the isoindole product. This maybe due to a limitation in the GaussView software. Although the NMR calculations for the isoindole product was run with deuterated benzene set as the solvent, GuaussianView does not have a deuterated benzene option for viewing the NMR results and the GIAO option was chosen instead.

The discrepancies between the predicted and literature shifts are due to many reasons. One of which is conformational flexibility, the calculated NMR only takes one conformer into account(static molecule) whereas the experimental NMR takes into account all the conformers of the molecule as bonds rotate and atoms exchange with each other. It is interesting to note the discrepancies between the predicted and literature shifts in both prodcuts increase with chemical shift(large discrepancy for more deshieled carbon atoms). This maybe another limitation in the computational approach.

1H NMR

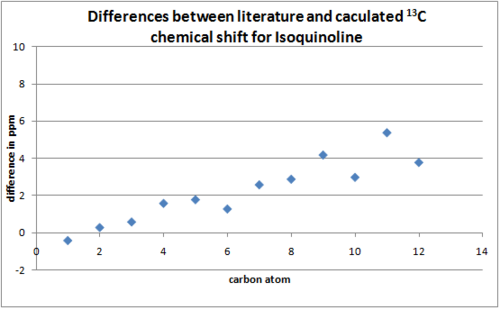

The 1H NMR provides another method to identify and differentiate between the two products. Both predicted chemical shift and coupling constants(calculated using Jannochio) were compared with literature[13]. The two graphs show the difference in chemical shift values, the hydrogen atoms on the x axis were plotted in order of chemical shifts(lowest to highest).

Table 12 : comparison of 1H NMR between literature and predicted values

The predicted 1H chemical shifts corresponds well with literature[13] but is less accurate compared to 13C.

Again the two products can be differentiated by the proton peak assigned to the hydrogens on C-11 of the isoindole product, these protons appear at low chemical shift(2.63ppm). This peak is not seen in the isoquinoline product, as the proton on the same carbon(labelled as C-9) now appear at a much higher chemical shift(9.12ppm) due to deshielding from the aromatic system.

For the isoindole prediction the major discrepancy(2.25ppm) in chemical shift was observed for the H atom on Nitrogen(9), this is due to the proton undertakeing fluxional exchange with the solvent in the experimental NMR resulting in a broad peak. The isoquinoline results follow the trend observed in 13C NMR, the accuracy of the predictions decreases with increase in chemical shift, the H atom on C-9 (carbon adjacent to the N atom) gave the largest error(1.51ppm). The major limitation in 1H NMR is that multiplicity of peaks can not be observed, one peak is predicated for each proton as all the protons are inequivalent in the computational approach.

However 3J coupling constants can be calculated using Jannochio, the calculation is based on the Karplus equation which takes the distance and dihedral angles into account. The results show good accuracy for aromatic protons but poor for the ethyl protons. This can be rationalised by conformational flexibility. In the experimental NMR, the distance and dihedral angles between the aromatic protons are more or less fixed due to the rigid structure of the aromatic rings whereas the rotation of bonds in the ethyl protons lead to variation in distance and dihedral angles.

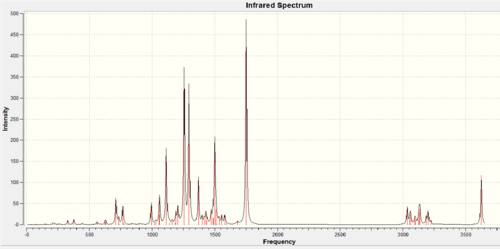

IR spectrum

The predicted IR spectra can further identify and differentiate the two products. The wavenumbers for stretches were corrected by 5% (as errors in the predicated values are systematically too high for stretches)before the vibrations were assigned. The sum of electronic and thermal free energy of molecules were obtained from the output files.

| IR Spectrum |  |

|

| sum of electronic and thermal free energy/Hartrees |

Table 12 : IR spectrum and free energy of the two compounds

Table 13 : assignment of vibrations

IR data for Isoindole: DOI:/10042/to-6455 IR data for isoquinoline: DOI:/10042/to-6456

The two predicted IR spectra are in good agreement with literature [13] which further confirms the proposed structures reported in the literature are correct. The major difference between the two IR spectra is the presence of N-H stretch and N-bend vibrations in the isoindole product. No N-H stretch or bend was observed in the isoquinoline product.

The calculated free energies(sum of electronic and thermal free energy) show the isoindole product is thermodynamically more stable than the isoquinoline product by 1.2Hartrees (753kcal/mol). This is in agreement with the initially calculation using MM2 force field, confirming the thermodynamic product(isoindole) is formed in the absence of base, and kinetic product(isoquinoline) is formed in presence of base.

Conclusion

In the example of regioselectivity investigated in the mini project, the NMR(13C and 1H) and IR predicted using molecular modelling proved effective in the characterisation of the two proposed products reported in the literature and the proposed structures can be confirmed as correct. The thermodynamic product was predicted to be isoindole 1, and the kinetic product is induced by the addition of base which is in agreement with mechanistic analysis. The limitations of the this modern computational method were observed and highlighted.

Prior examples showed molecular mechanics and semi-empirical molecular orbital theory predictions were accurate and useful in predicting the selectivity of reactions. As the use of this technique is at the cutting edge, there are still many other limitations in the approach that are not realised. But with research, the limitations can be minimised(improved knowledge of basis sets, density functionals and geometry optimisation) resulting in a more complete and very power method in predicting reaction outcomes in organic chemistry.

References

- ↑ N.L.J. Allinger, CJ. Am. Chem. Soc., 1977, 99, 8127: DOI:10.1021/ja00467a001

- ↑ W.C. Herndon, C.R. Grayson, J.M. Manion, J. Am. Chem. Soc.., 2002, 124, 1130: DOI:10.1021/jo01278a003

- ↑ R. Hoffman, R. Woodward, J. Chem. Soc., 1965, 87, 4388-4389: DOI:10.1021/ja00947a033

- ↑ K. Alder, G. Stein, Angew. Chem, 1937, 50, 514: DOI:10.1002/ange.19370502804

- ↑ A. G. Schultz and L. Flood, J. Org. Chem., 1986, 51, 838-841. DOI:10.1021/jo00356a016

- ↑ A. G. Shultz, L. Flood and J. P. Springer, J. Org. Chemistry, 1986, 51, 838.DOI:10.1021/jo00356a016

- ↑ Leleu, Stephane; Papamicael, Cyril; Marsais, Francis; Dupas, Georges; Levacher, Vincent. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, 2004, 15, 3919-3928.DOI:10.1016/j.tetasy.2004.11.004

- ↑ S. W. Elmore and L. A. Paquette, Tet. Letters, 32, 3. pp 319-322, 1991, DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-010.1021/ja00274a016 /10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-010.1021/ja00274a016

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 B. Halton, S.G.G. Russell, J. Org. Chem., 1991, 56, 5553: DOI:10.1021/jo00019a015

- ↑ B. Halton, R. Boese and H. S. Rzepa., J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 2, 1992, 447. DOI:10.1039/P29920000447

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 G. Socrates, Infrared and Raman Characteristic Group Frequencies, Third Edition, 2001, Pg. 65

- ↑ Mi, B.-X.; Wang, P.-F.; Liu, M.-W.; Kwong, H.-L.; Wong, N.-B.; Lee, C.-S.; Lee, S.-T. Chem. Mater. 2003, 15, 3148 {DOI| 10.1021/cm030292d}

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 B.W Hui, S. Chiba,Org. Lett. , 2009, 11 (3), 729-732 {DOI: 10.1021/ol802816k}