Rep:Mod:na2615ts exercise

Introduction

Potential Energy Surface (PES)

A potential energy surface is a mathematical function that provides the energy of a molecule as a function of its geometry. Due to the dependence on the geometry the PES, therefore, has the same dimensionality as the degrees of freedom of the molecule, 3N-6, where N is the number of atoms within the molecule. A potential energy surface will have various points which can be described using the first and second derivatives of energy. The first derivative will equate to zero, indicating that the position is a stationary point; this can be related to the force acting on the atoms in the molecule. The second derivative indicates the nature of the stationary point (minimum, saddle point, etc) and is equated to the force constant. The lowest energy point on a PES is the minima, which corresponds to a second derivative which is positive in all directions. A saddle point, that is located between two minima on a PES is called the Transition state, which is defined by a second derivative that is negative in one direction and positive in all other directions.[1]

Along a reaction coordinate the transition state has the highest potential energy, and in order for a reaction to pass from reactants to products, the system needs to possess enough energy to overcome the transition state energy, which is known as the activation barrier. In this lab, locating the minima and transition states of various reactions on a potential energy surface, permitted the visualisation of the reaction coordinate of each reaction by running an IRC calculation on the corresponding transition state.

Nf710 (talk) 11:38, 12 January 2018 (UTC) This is well written. A diagram and equations would have backed up your discussion

Methods of calculation

There are three methods of calculation that can be used to obtain the geometry of the transition state of a molecule in Gaussian. The first method requires knowledge of what the transition state structure may be, as it uses just the optimisation of the guessed transition geometry to produce an optimised transition state. As this method consists of only one step, it leads to a fast calculation, however, it is prone to error as the guessed transition state structure used for the optimisation is likely to be wrong. The second method also requires the knowledge of the transition state structure, however the transition state has a higher probability of being accurate than in the previous method, as the reactant atoms that are involved in bond formation are frozen in space at specific distances and the rest of the geometry is optimised to a minima before the optimisation of the transition state is conducted. The final calculation method is by far the most reliable method, although due to many steps involved it is the slowest method out of the three. Method 3, involves optimising the structure of the of the reactants or products to a minima. From this, the reactants can be optimised individually to a minima. From the individual reactant optimisations, the reactants can be arranged into a transition state structure, in which the bonds are frozen like in method two and optimised to a minima before being optimised to a transition state.

For the majority of the calculations run in this lab, the geometry of the transition state was obtained using method 3, as this lead to the most accurate structure.

Computational Methods

The potential energy surfaces for the three reactions analysed were generated using two different calculation methods on Guassian.

The first method used was PM6, which is a semi-empirical method. This method is based on Hartree-frock, but utilities many more approximations to calculate the Hamiltonian of the Schrodinger equation. The approximations are based on experimental data such as the ionization energies and the dipole moments of the molecules involved. If the environment of the molecules line up with the approximations made, the results produced are of a high accuracy and are calculated at a fast rate, however, if this if is not the case the results will be inaccurate.[2]

The second method used was B3LYP, this is a hybrid method which used density functional theory (DFT) to calculate most parts of the Hamiltonian accept for the exchange integral term, which it uses Hartree-Frock theorem. The calculation uses a 6-31G basis set to represent the electronic wavefunction. B3LYP produces calculations that are of a higher degree of accuracy than PM6 calculations, however, these calculations are more taxing on time.[1]

In this lab, PM6 was used as the main calculation method due to its speed and B3LYP was used to optimise the calculations that were produced using PM6, to gain results that had a greater accuracy.

Nf710 (talk) 11:40, 12 January 2018 (UTC) This is really well understood. You have read beyond the script here. Well done.

Exercise 1: Reaction of Butadiene with Ethylene

(Fv611 (talk) Excellent job throughout the whole exercise. Very well done! Only note is to pay attention to meaning of the significant figures of your bond length measurements....are we really able to measure distances with 10^(-15)m precision?)

Transition State Molecular Orbital Diagram

The molecular orbital diagram shown in figure 2 was constructed using the molecular orbitals of the reactants and the molecular orbitals produced by the transition state geometry. The transition state HOMO and LUMO was formed through the interaction of the ethylene HOMO and the butadiene LUMO. From the molecular orbitals displayed in table 1, a plane of symmetry can be seen in the HOMO of ethylene and the LUMO of butadiene, therefore these two orbitals are symmetric. The HOMO-1 and LUMO+1 orbitals are formed due to an interaction between the LUMO of ethylene and the HOMO of butadiene, the corresponding orbitals in table 1 are shown not to have a vertical plane of symmetry, therefore, the two orbitals are antisymmetric. From the observations made, it is possible to draw up the conclusion that in order for orbitals to overlap and produce molecular orbitals they need to be of the same symmetry. Therefore, it can be said that reactions, in which the orbitals do not have the same symmetry, are forbidden as the orbitals cannot interact to produce molecular orbitals, and reactions, where the orbitals have the same symmetry are allowed, as the atomic orbitals can interact to produce molecular orbitals.

The overlap integral is a quantitative measure of the degree to which two orbitals interact,SAB. When the orbitals are of the same symmetry, which will lead to an interaction, the overlap integral will have a non-zero value. And when the orbitals are of different symmetries, an interaction will not occur and so the overlap integral will be equal to zero. Therefore, interactions between symmetric-symmetric and antisymmetric-antisymmetric orbitals will lead to non-zero overlap integrals, and the interaction between symmetric-antisymmetric orbitals will give an overlap integral of zero.

Generally, when atomic orbitals interact, two molecular orbitals are formed, the bonding orbital formed is more stabilised than the atomic orbitals and the anti-bonding orbital is more destabilised. However, from figure 2, it can be seen that this is not the case for the interaction between the two symmetric atomic orbitals. This is due to the fact that the molecular orbitals shown in figure 2 are of the transition state rather than the products, and as there is an activation barrier, this needs to be overcome in order for the reaction to occur, which is why TS HOMO sits at a higher energy than the ethylene HOMO that contributes to it. The TS HOMO orbital has a greater contribution from the ethylene HOMO than the LUMO of butadiene, which is shown by it being closer in energy to the ethylene HOMO. However, this does not compare to the contribution that the TS LUMO receives from the LUMO of butadiene as the two orbitals are very close in energy to each other only differing by a value of -0.002 Hartree.

Table 1: Molecular orbitals of the HOMO and LUMO of Ethylene, Butadiene and the Transition state

| Ethylene HOMO | Ethylene LUMO | Butadiene HOMO | Butadiene LUMO | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TS HOMO-1 | TS HOMO | TS LUMO | TS LUMO + 1 | ||||||||

C-C bond length analysis

Table 2: The C-C bond lengths for the reactants, transition state and product

| C-C Bond (Å) | Ethylene | Butadiene | Transition State | Cyclohexene |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1-C2 | - | 1.33344 | 1.37978 | 1.50084 |

| C2-C3 | - | 1.47077 | 1.41111 | 1.33696 |

| C3-C4 | - | 1.33344 | 1.37968 | 1.50083 |

| C4-C5 | - | - | 2.11532 | 1.53718 |

| C5-C6 | 1.32744 | - | 1.38171 | 1.53461 |

| C6-C1 | - | - | 2.11415 | 1.53717 |

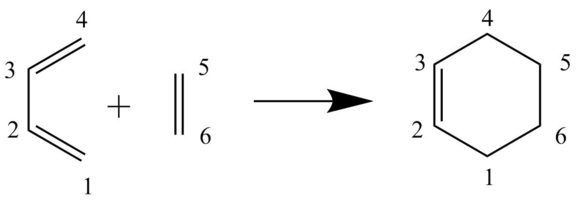

As the reaction proceeds from the reactants to the transition state, a difference in the bond lengths occurs. Table 2, shows that as the reaction moves towards the transition state the C5-C6 bond corresponding to ethylene increases from 1.32744 to 1.3871Å, this is due to the hybridisation of the carbons changing from sp2 hybridisation to sp3 hybridisation. The reduction in the s character results in longer bond lengths. The same is true for C1-C2 & C3-C4 (Figure 1) which corresponds to the sp2-sp2 carbon double bonds in butadiene (Figure 1). The C2-C3 single bond has length of 1.47077Å which is shorter than the length of a normal C-C single bond at 1.54Å [3], the reasoning behind this is that the two carbons that contribute to the single bond are both sp2 hybridised, and so the bond length would be shorter than that associated with normal sp3-sp3 C-C single bonds. As the reaction proceeds, the C2-C3 of butadiene can be seen to decrease in bond length from 1.47077Å to 1.4111Å in the TS and 1.33696Å in the products, this reduction in bond length occurs due to the increased electron density around the C-C as it eventually forms a C=C double bond in the product (cyclohexene).

As the reaction proceeds, the formation of bonds not present in the reactants also form. Table 1, shows an interaction between C4-C5 & C6-C1 (Figure 1) in the transition state, which corresponds to interactions between the carbons of butadiene and ethylene which have respective lengths of 2.11532Å and 2.11415Å. As a normal sp3-sp3 C-C bond has a length of 1.54Å the lengths are too long to correspond to bonds. The interactions are shorter than the van der Waals radii between two carbon atoms of 3.4Å (van der Waal radii of single C = 1.7Å), therefore, the lengths indicate that the carbon atoms of butadiene and ethylene were drawing closer together in the TS as they were beginning to interact. The bond lengths between these atoms shorted to 1.5372 in the product as two new sp3-sp3 C-C bonds were formed. The bond lengths between the carbon atoms in the product (cyclohexene) corresponds two the typical length of a sp2-sp2 carbon double bond (1.33Å)[3] and sp3-sp3 carbon single bond, however there are two single bonds between C1-C2 and C3-C4 which have slightly shorter lengths, which is due to the slight overlap of electron density from the double bond between C2-C3.

Transition State Vibration

The vibration shown in the above jmol, corresponds the transition state geometry and is therefore negative in frequency. The vibration shows the approach the ethylene carbons towards the terminal carbons of butadiene. As the two reactants move towards each other at the same rate, the formation of the two new bonds is synchronous as they are formed in a concerted fashion. The synchronous bond formation can also be seen in the IRC of the reaction, as the animation shows that the two bonds are formed at the same time. File:EXERCISE1 TS ETHYLENE+DIENE IRC.LOG

File:EXERCISE1 PRODUCT CYCLOHEXENE NA2615.LOG

File:EXERCISE1 TS ETHYLENE+BUTADIENE NA2615.LOG

Exercise 2 : Reaction of Cyclohexadiene and 1,3-Dioxole

Diels-Alder Transition State MO

(Fv611 (talk) Again, very good MO diagrams. You could have added a discussion on the differences in relative energies between the endo and exo case.)

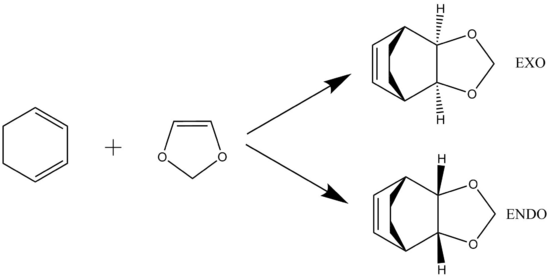

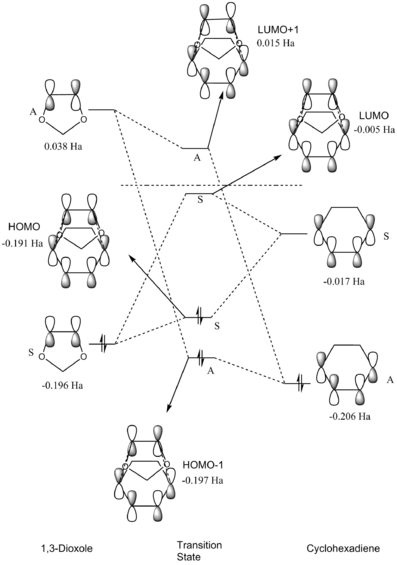

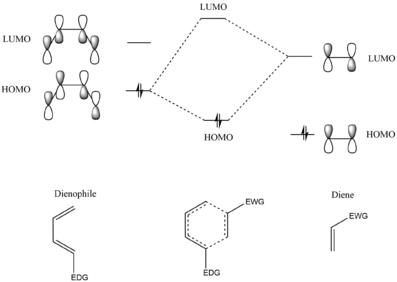

In a normal Diels-Alder reaction, the dienophile is electron deficient and the diene is electron rich. When looking at the orbitals involved in the reaction; the electron deficient dienophile has a low energy LUMO that interacts with the high energy HOMO of the electron-rich diene. As these molecular orbitals have a small energy gap, the overlap between the orbitals is strong. This interaction leads to the formation of the HOMO and LUMO of the product (figure 6). However, this is not the case for the reaction between cyclohexadiene and 1,3-dioxole. In this reaction, the diene (cyclohexadiene) is electron deficient and the dienophile (1,3-dioxole) is electron rich. This has an effect on the energies of the reactant molecular orbitals. From figures 4 & 5, the HOMO of the dienophile interacts with the LUMO of the diene, this interaction occurs as the electron donating nature of the oxygen atoms in 1,3-dioxole increases the electron density around the double bond, therefore, increasing its energy. This interaction leads to the formation of the transition state HOMO and LUMO. As the orbital interactions are opposite to that which occurs in a normal Diels-Alder reaction, the reaction is referred to as an inverse electron demand Diels-Alder reaction.[4] Although the reaction is inverse electron demand, it is still thermally allowed. This is due to the fact that the reaction still obeys the Woodward-Hoffmann rule as the reaction has one (4q+2)s component and no (4r)a components.

From figures 4 & 5 it can be seen, that the HOMO of the dienophile and LUMO of the diene (Table 3) are both symmetrical and result in the formation of symmetrical HOMO and LUMO for the transition state structure. The same goes for the HOMO-1 and LUMO+1 which are formed by the antisymmetric HOMO of the diene and the LUMO of the dienophile. Compaing the two molecular orbital diagrams, it is possible to see that the HOMO of the endo transition state is lower in energy the HOMO of the exo transition state.

Table 3: The molecular orbitals of the EXO and ENDO transition state

| HOMO-1 of ENDO TS | HOMO of ENDO TS | LUMO of ENDO TS | LUMO+1 of ENDO TS | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HOMO-1 of EXO TS | HOMO of EXO TS | LUMO of EXO TS | LUMO+1 of EXO TS | ||||||||

Thermochemistry

From the calculated thermochemistry data (Figure 4), it can be seen that the activation barrier for the endo pathway is less endothermic than that of the exo pathway. The activation barrier is the energy required to get the reaction to the transition state. As less energy is required for the endo pathway to get to the transition state, it is the more kinetically favoured pathway. This can be explained by looking at the HOMO TS orbitals of the endo and exo pathway (Table 5). The endo HOMO shows an interaction between the p orbitals on the two oxygen atoms of the dienophile and the pi orbitals of the conjugated diene, this interaction in addition, to the primary bonding interaction between the pi system of the dienophile and diene, results in the transition state of the endo product being of a lower energy than the exo transition state. Table 5, shows that the p-orbitals on the oxygen of the exo HOMO do not interact with the pi system of the diene, as it does not have the correct geometry to do so.

Table 4, also shows that the reaction energy of the formation of the endo product is more exothermic than that of the exo product. This means that out of the two pathways, the endo product is also the most thermodynamically stable product. This is also a result of the secondary orbital interactions that are also present in the HOMO of the endo product. Another factor for this, could be the result of the dioxole group being in the same plane as the bridgehead in the exo product, as these groups could be involved in some unfavourable interactions, leading to the exo product having a more endothermic reaction energy than the endo product.

Table 4: The thermochemistry data for the formation of the ENDO and EXO products for the reaction between cyclohexadiene and 1,3-dioxole

| Pathway | Activation barrier

(kJ/mol) |

Reaction energy

(kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| Endo | 158.47 | -68.75 |

| Exo | 166.29 | -65.16 |

Table 5: The HOMO of the ENDO and EXO transition state showing secondary orbital interactions

| ENDO HOMO SECONDARY INTERACTIONS | EXO HOMO SECONDARY INTERACTIONS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Corresponding log files

File:EXERCISE2 TS B3LYM EXO na2615.LOG

File:EXERCISE2 TS B3LYP ENDO NA2615.LOG

File:EXERCISE2 TS PM6 EXO IRC NA2615.LOG

File:EXERCISE2 TS PM6 ENDO IRC NA2615.LOG

File:EXERCISE2 EXO PROUDCT B3YLM NA2615.LOG

File:EXERCISE2 PRODUCT B3YLM ENDO NA2615.LOG

File:1 3 DIOXLONE MIN BY3LYP NA2615.LOG

File:EXERCISE2 MIN CYCLOHEXADIENE B3LYP NA2615.LOG

Nf710 (talk) 11:50, 12 January 2018 (UTC) This is very nicely written section again. You could have proved the electron demand qualitatively by doing an energy calculation with both reactants in the same plan. Your energies are correct and therefore have come to the correct conclusion. A diagram would have been nice to complement your discussion on sterics

Exercise 3: Diels-Alder vs Cheletropic

IRC

|

|

|

The below figures show the IRCs of the three different products that form from the reaction of xylyene and SO2. The IRC is the intrinsic reaction coordinate and shows how the reaction proceeds from the reactants to the products. The IRCs shown for the endo and exo products in figures 8 & 9, show that the formation of the new bonds is asynchronous as the bond between the diene and oxygen of the dienophile forms before the bond between the sulfur atom and the diene. The IRC for the cheletropic reaction (figure 10) shows that formation of the new bonds is synchronous as both ends of the diene (xylylene) forms bonds with the sulfur atom at the same time.

Thermochemistry

(You swapped the labels for endo and exo in Fig. 11 Tam10 (talk) 15:46, 9 January 2018 (UTC))

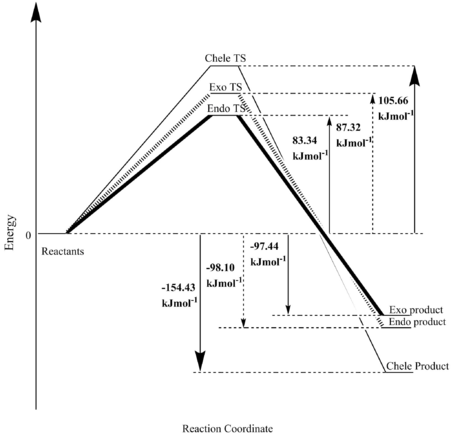

From the calculated energies seen in table 6, the endo transition state has the lowest energy activation barrier, making it the least endothermic out of the three. This low activation barrier is the result of the stabilisation that the endo transition state receives due to the additional interaction between the p orbital of an oxygen atom in SO2 and the pi orbitals in xylylene. The endo product is, therefore, the kinetic product, as its transition state barrier can be passed through quickly as the energy required for it is the lowest.

(Endo- and exothermicity are related to reactants and products, not the TS or barrier. Tam10 (talk) 15:44, 9 January 2018 (UTC))

The cheletropic transition state has the highest activation barrier, this is due to ring strain, as the cheletropic reaction leads to the formation of a five-membered ring which is more strained than the six-membered ring that forms in the diels-alder reaction.

From the reaction energies (table 6), it is clear to see that the cheletropic reaction is by far the most exothermic reaction. This is due to the energies of the bonds formed in the reaction. The product of the cheletropic reaction consists of two S=O double bonds, each contributing 522 kJmol-1 to the reaction energy, whereas the diels-alder product has only one S=O double bond and an S-O single bond which contributes an energy of 265kJmol-1. This leads to the energy of the cheletropic reaction being more exothermic than both the endo and exo products of the diels-alder reaction. Therefore, the cheletropic results in the most thermodynamic product, but as this is not also the kinetic product, this thermodynamic product will form when the reaction that forms the kinetic product is reversible.

(Do you have a reference for these values? I get ~368 kJ/mol for S-O. Taking the difference of bond enthalpies from a table actually agrees very well with the calculations Tam10 (talk) 15:44, 9 January 2018 (UTC))

Xylylene is a very unstable molecule, this is due to its need to form an aromatic ring system in order to stabilise its energy. Looking at the IRC of the three products, the formation of the aromatic ring system occurs in xylylene before it forms new bonds with SO2.

Table 6: The energies of the activation barrier and reaction for the products of the Diels-alder and Cheletropic reactions

| Pathway | Activation barrier

(kJ/mol) |

Reaction energy

(kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| Endo | 83.34 | -97.44 |

| Exo | 87.32 | -98.10 |

| Cheletropic | 105.66 | -154.43 |

Alternative Diels-Alder reaction

|

|

The alternative Diel-Alder reaction occurs between the cis diene in the cyclohexadiene ring of xylylene and SO2. The resulting products each have a bridging S-O bond between the two carbons in the ring of xylylene. By calculating the thermochemistry of the reaction, the endo product was found to be both the thermodynamic and kinetic product out of the two, as it has a lower activation barrier and reaction energy (Table 7). Comparing these results to that of the normal diels-alder reaction (table 6) it can be seen, that the reaction energy of the endo and exo products for the alternative pathway was significantly higher than that of the normal pathway. This is due to the fact that the products of the alternative pathway are less stable due to the absence of the aromatic system which is formed in the normal pathway. The activation energies of alternative pathway transition states are also of a higher energy, therefore the reactions would be slower as more energy is needed to reach the transition state.

Table 7: The energies of the activation barrier and reaction for the products of the alternative Diels-alder reaction

| Pathway | Activation barrier

(kJ/mol) |

Reaction energy

(kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| Endo | 113.56 | 17.83 |

| Exo | 121.40 | 22.28 |

Corresponding log files

File:XYLYLENE MIN PM6 NA2615.LOG

File:CHE MIN PRODUCT PM6 NA2615.LOG

File:EXERCISE3 DA EXO TS PM6 PRODUCT ALTERNATIVE NA2615.LOG

File:EXERCISE3 DA ENDO TS PM6 PRODUCT ALTERNATIVE NA2615.LOG

File:EXERCISE3 DA ENDO PRODUCT NA2615.LOG

File:EXERCISE3 DA EXO PRODUCT NA2615.LOG

Conclusion

In conclusion, PM6 and B3LYP was used successfully to calculate the geometries of the transition states and products of three different reactions. Only exercise 2 utilised B3LYP calculations to find the geometries of the reactants, transition state and product. This is due the fact that the other two exercises used calculation method three (see introduction), this method produced geometries that closely resembled the true structures of the reactants, products and transition states, therefore, PM6 was sufficient enough to give accurate calculations. In exercise 1, PM6 allowed the identification of the bond lengths that corresponded to ethylene, butadiene and cyclohexene, the values obtained from the calculation were found to be in accord with the literature values. Exercise 2, used B3LYP to find the energies of the transition state molecular orbitals and was used to find the activation barrier and reaction energies for the inverse electron demand diels-alder reaction in which the endo product was found to be the thermodynamic and kinetic product. Exercise 3, used PM6 to find the activation barrier and reaction energies for the diels-alder and cheletropic reactions, from the results generated, the endo product was found to be the kinetic product and the cheletropic product was the thermodynamic product.

Bibliography

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 J. J. W. McDouall, Computational Quantum Chemistry, The Royal Society of Chemistry, 2013, 1-62.

- ↑ J. Řezáč, J. Fanfrlík, D.Salahub and P. Hobza, J. Chem. Theory Comput., 2009, 5, 1749–1760

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 A.K.Srivastava, Organic Chemistry Made Simple., 2008, 6

- ↑ D. L. Boger and M. J. Kochanny, J. Org. Chem., 1994, 59, 4950–4955