Rep:Mod:mtr09mod3

3rd Year Computational Chemistry Project - Matthew Reynolds

Module 3 - Characterisation of Cycloadditon Transition States

Cope Rearrangement of 1,5 - Hexadiene

Introduction

So far, Computational Chemistry has clearly been shown to be a useful tool in the determination of the lowest energy conformations and vibrational modes of within small organic molecules Module 1. Its use was further expanded in Module 2, whereby computational methods were used to predict and rationalise the preference of phosphine ligands to be situated trans- to one another is octahedral Molybdenum complexes. Furthermore, the estimation of the relative sizes and shapes of the bonding Molecular Orbitals that make up Al2Br2Cl4 were calculated, which allowed us to make sense of the preference for the two large halogen atoms to be situated cis- to one another. This module aims to demonstrate the use of computational methods in the prediction of transition states in pericyclic reactions.

In the first part of this module, the transition states of the [3,3] sigmatropic [Cope] rearrangement of 1,5- Hexadiene (shown below) will be subjected to computational analysis.

Study of this reaction mechanism by computational methods, such as whether it proceeds via a biradicaloid or an aromatic transition state, is already well documented in the literature[1]. This particular module aims to determine the preference of the reaction to proceed via a chair or a boat conformation through investigation into the lowest energy conformations of the transition state structures. It has been stated by Maluendes et al. (1990) that the chair transition state has been determined lower in energy than the boat transition state. [2]

During this module, structures were drawn, viewed and analysed on the GausssView 5.0 software, whilst calculations for optimisations and frequency analysis were performed on the Gaussian 09 software on the SCAN server. The transition states were modelled on the Gaussview 5.0 software, through the optimisation of the reactants to a transition state. The lowest energy pathway to the transition state was also analysed by performing an Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate optimisation on the structures.

Optimising the Reactants and Products

There are several possible conformations that 1,5 - hexadiene can occur in, due to the free rotation about the C-C single bonds. Each of these will be analysed by performing an Optimisation calculation on them, using the Hartree-Fock method, under a 3-21G basis set. It was expected that the 10 staggered (Antiperiplanar or Gauche/Synclinal) conformations would be of a lower relative energy than the eclipsed (Anticlinal or Synperiplanar) conformations. However, the prediction of the preference between the Anti and Gauche conformers is rather more difficult to make. Factors, such as Van der Waals attractions/ Pauli repulsions and orbital interactions are difficult to quantify without computational means.

The results of the optimisation calculations for each of the 10 conformations of staggered 1,5- Hexadiene, whose structures were cleaned beforehand, are shown in Table 1 below. Please note: clicking on the name of the conformation will provide a 3D Jmol link to the structure, and the LOG files for each of the optimisations can be seen by following the link in the references provided. The point groups were determined by using the 'Symmetrize' option on the Gaussview interface.

Please note: for conversions into kcal mol-1, a conversion factor of 1 Ha = 627.5 kcal mol-1 was used.

| Conformation + 3D Jmol Link | Total Energy/Ha | Point Group | Relative Energy/kcalmol-1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti 1 Conformation [3] | -231.69260 | C2 | 0.04 |

| Anti 2 Conformation [4] | -231.69254 | Ci | 0.08 |

| Anti 3 Conformation [5] | -231.68907 | C2h | 2.25 |

| Anti 4 Conformation [6] | -231.69097 | C1 | 1.06 |

| Gauche 1 Conformation [7] | -231.68772 | C2 | 3.10 |

| Gauche 2 Conformation [8] | -231.69167 | C2 | 0.62 |

| Gauche 3 Conformation [9] | -231.69266 | C1 | 0.00 |

| Gauche 4 Conformation [10] | -231.69153 | C2 | 0.71 |

| Gauche 5 Conformation [11] | -231.68962 | C1 | 1.91 |

| Gauche 6 Conformation [12] | -231.68916 | C1 | 2.20 |

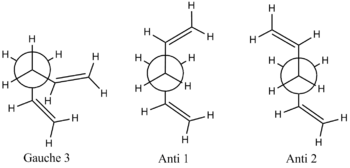

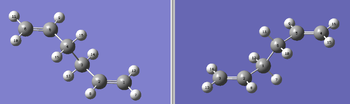

First of all, it is interesting to note that there is no overall trend (a trend would constitute all the anti conformers being more energetically stable than all the gauche conformers or vice versa) in these results. The most stable conformation is the gauche 3 conformer. This in itself is surprising, as the it has been calculated (by H. Rzepa[13], using a 6-311G(d,p) DFT method) that for butane, the antiperiplanar conformation is approximately 2 kcalmol-1 more stable than the gauche conformation. The disparity between the relative conformational stability of these two structures could be due to the amplified nature of the Van der Waals attraction in the more electron-rich hexadiene species, it could also be due to an computational error arising from the fact that a lower level (and therefore less accurate) HF/3-21G method and basis set were used for the hexadiene optimisations. The 3 most energetically stable structures are shown in their Newman projection forms below:

To allow an effective comparison with the results obtained by H. Rzepa, it was decided that the three most stable conformers of 1,5- Hexadiene would be subjected to approximately the same level of computational analysis, by repeating the optimisation calculation, this time using a DFT/B3LYP method, under a 6-31G* basis set. It was expected that the more comprehensive optimisation would produce more accurate results.

The results of this further optimisation, along with the 3D links and LOG files, are shown below:

| Conformation + 3D Jmol Link | Total Energy/Ha | Point Group | Relative Energy/kcalmol-1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti 1 Conformation [14] | -234.61178 | C2 | 0.00 |

| Anti 2 Conformation [15] | -234.61171 | Ci | 0.04 |

| Gauche 3 Conformation [16] | -234.61132 | C1 | 0.29 |

These results clearly show a greater agreement with the expected results. In comparison to the energetic stabilities of the conformations, as determined by the HF method, both the Anti 1 and Anti 2 conformations have been determined to be more energetically stable than the Gauche 3 conformation under DFT analysis. This is due to the optimum orbital overlap between the antiperiplanar allyl groups, which is not seen for the Gauche 3 conformation. Furthermore, in Anti configurations, stearic strain resulting from the Pauli repulsions between the two larger allyl groups is reduced significantly with respect to the Gauche configurations. It should be noted that, even with these interactions taken into account, the geometries of the DFT-optimised conformers were very similar to those optimised by the Hartree-Fock method.

Infrared Analysis of 1,5 Hexadiene Conformations

So as to determine the accuracy of the geometry optimisation calculations, a frequency analysis was performed on the DFT Optimised Anti 1, Anti 2 and Gauche 3 conformations. It is possible to confirm how effectively a species has been optimised by analysing the low/negative frequency modes of vibration.

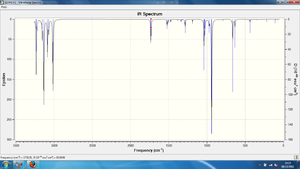

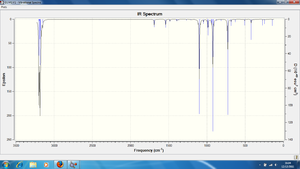

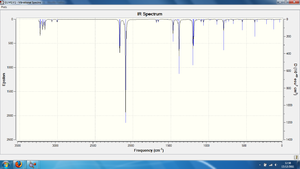

It was observed that no negative vibrational modes were present in the vibrational data for any of the conformations, indicating that all three had been optimised to a minima (as opposed to a transition state maxima, which would produce a negative vibrational frequency, this will be demonstrated further when optimising the chair and boat transition structures of the Cope Rearrangement). The predicted Infrared spectrum for the Anti 1 conformation is shown below in Figure 3 .

Aside from the typical, expected peaks due to C-H and C-C Stretching and Bending modes, a medium intensity peak in the region of ~1700cm-1 can clearly be seen. This is due to the symmetric and asymmetric stretching modes of the C=C bonds. This is surprising, as the literature[17] states that typical C=C stretches occur in the region 1620-1680cm-1. It is highly possible that the presence of two alkene moieties in a single molecule could increase the vibrational frequency of the C=C stretch. A summary of these vibrational modes for each of the three DFT-optimised conformers is shown in the table below:

| Conformation | Symmetrical C=C Stretching Mode/cm-1 [Intensity] | Asymmetrical C=C Stretching Mode/cm-1 [Intensity] |

|---|---|---|

| Anti 1 Conformation [18] | 1732 [4.73] | 1735 [13.57] |

| Anti 2 Conformation [19] | 1731 [0.00] | 1734 [18.13] |

| Gauche 3 Conformation [20] | 1732 [2.24] | 1733 [6.89] |

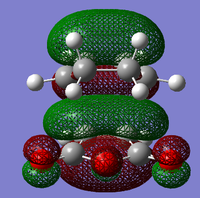

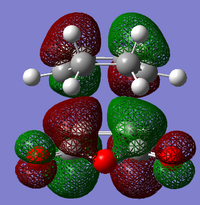

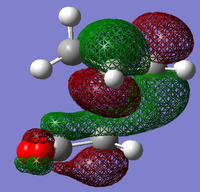

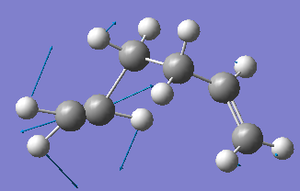

Animations of both the symmetric and asymmetric modes of stretching have been taken for the Anti 1 conformer, which are shown below:

It was interesting to note that, for the C=C vibrational modes of the Gauche 3 conformer, the two C=C stretching characters that make up the symmetric and asymmetric vibrational modes oscillate at the same frequency, however the magnitudes of these vibrations were not the same.

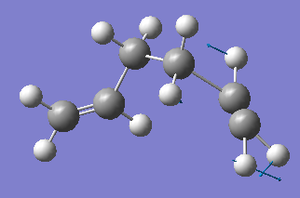

For the asymmetric C=C stretching mode, the C=C bond on the left of the diagram below has a far greater amplitude of oscillation (as shown by the relative sizes of the displacement vector arrows) than the C=C bond on the right of the diagram (yet their frequencies of vibration are equal).

Whereas, for the asymmetric C=C stretching mode, the C=C bond on the right of the diagram below has a far greater amplitude of oscillation (as shown by the relative sizes of the displacement vector arrows) than the C=C bond on the left of the diagram (yet, once again, their frequencies of vibration are equal).

It is possible that the difference in amplitudes between the two constituent C=C stretches that make up the symmetric and asymmetric modes for the Gauche 3 conformer could be due to the low symmetry of the conformation (C1), especially as this phenomenon is not observed for both the higher symmetry Anti 1 and Anti 2 conformations.

Thermochemical Analysis of 1,5 Hexadiene Conformations

The DFT vibrational analysis performed in the previous section also provides us with the thermochemical data for each conformation at a pre-defined temperature in the LOG file. The energy parameters under consideration are as follows:

Sum of electronic and zero point Energies (εo + εZPE): This is the total electronic energy + the zero point vibrational energy.

Sum of electronic and thermal Energies (εo + Etot): This is the total electronic energy + the total internal thermal energy, which consists of vibrational, rotational and translational energy.

Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies (εo + Hcorr): This is the total electronic energy + the correction to the enthalpy due to internal energy.

Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies (εo + Gcorr): This is the total electronic energy + the Gibbs free energy due to internal energy.

Note: 0K was defined as 0.0001K in the Gaussian Input file, otherwise the calculation would automatically fail.

Anti 1 results at 298.15K [at 0K]/Ha Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies= -234.469318 [-234.468881] Sum of electronic and thermal Energies= -234.461979 [-234.468881] Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies= -234.461035 [-234.468881] Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies= -234.500250 [-234.468881]

.

(LOG file for the 0K Optimisation for Anti 1 is shown in the attached reference)[21]

Anti 2 results at 298.15K [at 0K]/Ha Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies= -234.469204 [-234.468766] Sum of electronic and thermal Energies= -234.461857 [-234.468766] Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies= -234.460913 [-234.468766] Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies= -234.500777 [-234.468766]

(LOG file for the 0K Optimisation for Anti 2 is shown in the attached reference)[22]

Gauche 3 results at 298.15K [at 0K]/Ha Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies= -234.468693 [-234.468256] Sum of electronic and thermal Energies= -234.461464 [-234.468256] Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies= -234.460520 [-234.468256] Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies= -234.500105 [-234.468256]

(LOG file for the 0K Optimisation for Gauche 3 is shown in the attached reference)[23]

The most striking trend from these results is that, at 0K, the sums of all the energy and enthalpy parameters are equal, whereas at 298.15K there is a clear difference between four different energies and enthalpies. This is to be expected, as there is no thermal contribution to the energies at 0K, therefore, only the total electronic energy (and zero point energy) is considered for all of the parameters.

It is also noted that as the temperature is increased from 0K to 298.15K, the total energies of the system tend to increase (i.e. becomes more positive), however, the parameter for the free energy correction decreases with increasing temperature. This is to be expected, and can be rationalised by taking consideration of the Gibbs Free Energy equation: G = H - TS. Increasing the simulated temperature would decrease the the total Gibbs Free Energy of the system, as entropic contributions are amplified at greater temperatures.

A potential further experiment could be to determine the exact relationships between each of the energy parameters and temperature or pressure. To do this, one would have to open the Gaussian Input files for the frequency optimisation, and alter the temperature (or pressure) at which the the calculation is run. A range of temperatures (or pressures) could be tested, which could be plotted on a graph against the energetic parameter under consideration (taken from the LOG file), to show the relation between the two parameters. This can be taken one step further, by altering both the temperature and the pressure of the calculation and plotting them as a 3D energy surface. However, this latter experiment would be both time consuming and effectively futile.

Optimisation and Frequency Analysis of the Chair and Boat Transition Structures

This section aims to expand upon the thermochemical analysis of the different conformations of the reactant molecule, 1,5-Hexadiene, and the relevance of this data in predicting the preferred geometry and the relative energetic stability of the transition states in the Cope Rearrangement reaction.

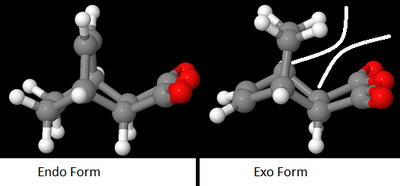

As mentioned in the Introduction, the Cope rearrangement can occur via one of two transition states, the chair and the boat conformers (shown below):

The structures of the transition states were produced from their constituent allyl (CH2CHCH2) fragments. Therefore, prior to any modelling and optimisation of either the chair or boat conformers, the allyl fragment needed to be modelled and optimised.

The allyl fragment was drawn on GaussView 5.0 and optimised using the HF method under a 3-21G basis set. As the allyl fragment is a small, simple molecule, the use of this low level basis set is sufficient for optimisation. The optimised structure of this fragment can be viewed in 3D in the link provided. The LOG file for this optimisation is shown in the reference.[24]

Chair Conformation

The optimised fragment was then doubled up to form a pseudo-chair conformation of transition state, as shown in Figure 8 above. The interatomic distance between two terminal carbon atoms of the allyl fragments that were to undergo bonding was set to 2.2Å.

This transition state was then subjected to two separate paths of optimisation: The first path (a) involves computing the Hessian matrix, which is updated with each optimisation, whilst the second path (b) requires the freezing of the reaction coordinate and the optimisation of the rest of the molecule, followed by the unfreezing of the reaction coordinate, and optimising to a transition state.[25] Method (b) is generally better for larger systems, as the freezing and unfreezing of the reaction coordinate produces a reasonable 'first guess' at the Hessian matrix, and therefore reduces the time taken for the fully optimised Hessian matrix to be computed.

Method a): The pseudo-chair structure was first to be optimised to a transition state by computing the Hessian matrix at each step in the optimisation. This was achieved by selecting Optimise to a TS(Berny), using the HF method under a 3-21G basis set on the Gaussian calculation setup.

The resulting 3D Jmol structure from this optimisation is shown in the link provided.[26] It was noted that the main difference between the geometry of the two pre-optimised allyl fragments in the input file and the transition state produced from the Gaussian calculation was the orientations of the hydrogen atoms. In the pre-optimisation form, the hydrogen atoms were situated in the plane of the allyl fragments, whereas, in the transition state form the hydrogen atoms attached to the terminal carbons of the fragments were bent out of the plane slightly. Furthermore, it was found that the interatomic distance between the two sets of bonding atoms had decreased from 2.20Å to 2.02Å.

A frequency analysis was also performed during the optimisation method, to determine whether the expected negative (imaginary) frequency had been produced. As expected, a vibrational mode at -818cm-1 [Intensity: 5.86] corresponding to the Cope rearrangement was observed. This confirms that the model had been optimised to a transition state, as opposed to an energy minimum. An animation of this negative vibrational mode is shown below:

Method b): The pseudo-chair structure was also to be optimised to a transition state by using the 'redundant co-ordinate method', in which two optimisation steps (the first to freeze the reaction co-ordinate and optimise the rest of the structure, the second to optimise to a transition state, as with Method a)) were required.

This was achieved by selecting Redundant Co-ordinate editor, and freezing the co-ordinates between the two sets of terminal carbon atoms. This system was then optimised to a minimum using the HF method under a 3-21G basis set on the Gaussian calculation setup. The resulting structure [27] from the initial optimisation is shown in the 3D Jmol link provided, with the LOG file shown in the references. The interatomic distance between the two sets of bonding carbon atoms was determined to be 2.20Å, which is unsurprising, as this was the value set by the redundant co-ordinate editor.

This structure was further optimised using a modified normal hessian method, in which the co-ordinates between the terminal carbons are unfrozen, and a force constant derivative is calculated (using HF/3-21G) instead. The resulting transition state [28] is shown in the link provided. Interestingly, the interatomic distance between the two ends of the allyl fragment that were to undergo bonding had decreased to 2.02Å as with the normal Hessian matrix method. The frequency of the imaginary vibration was the same as that for the Hessian matrix method, at -818cm-1, with the intensity of the vibrational mode being given as a slightly higher 5.93. This imaginary frequency confirms that the structure had been optimised to a transition state, as opposed to minimum (which would not have produced negative frequency vibrations). An animation of the negative vibrational mode is shown below:

Boat Conformation

The boat conformation of the transition state was required to be produced in a slightly different method to that of the chair conformation. For this QTS2 method, the reactant and product molecules had to be specified, so that the calculation could estimate the structure of the transition state between them.

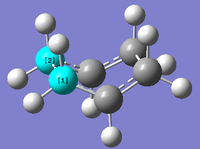

The Anti 2 fragment was determined to be the reactant molecule. The atom labels of the reactant (on the left of the diagram below) and the product (on the right of the diagram below) had to correspond to each other in the manner shown below (Figure 9 ):

An initial QTS2 Gaussian calculation was set up and run on the Gaussian 09 software. It was found that the initial optimisation failed, as the fragments were unable to rotate about the C-C bonds to produce the correct structure. The geometry of the fragments had to be altered to allow the transition state to be constructed. The dihedral angle along the four carbon backbone of both structures was changed to 0o, and the triatomic angle between the three 'inside' carbon atoms (for example, C3, C4 and C5 in the reactant molecule below) was reduced to 100o. Both the reactant and product molecules were aligned in the fashion shown in Figure 10 below:

A second optimisation under the QTS2 method was performed, which yielded the following boat transition state [29]

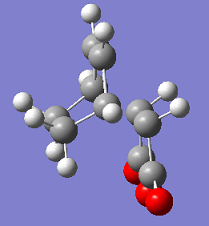

NOTE: For some reason, the Jmol image produces the 'transition state' dashed bond as some form of ladder-style bond. The origin of this error is unknown, therefore, an image of the transition state (after a further DFT B3LYP/6-31G* optimisation, though) is also provided below (the 'dashed bond' is between the two cyan coloured carbon atoms):

The interatomic distance between the two bonding ends of the transition state was determined to be 2.14Å. The frequency of the imaginary vibration was observed at -840cm-1, with the intensity being given as 1.59. This indicates that the structure has been optimised to a transition state, as opposed to a minimum.

An animation of this vibrational mode is shown below, however, to view the animation, you are required to click on the image on this page, then click on the image again in the page you're directed to. This should direct you to an animation of the negative vibrational mode.

Further Optimisation using Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate Methods (under HF/3-21G)

From the HF-optimisations of the transition states performed in the previous section, it is impossible to determine which conformation of 1,5- Hexadiene the transition state will collapse into. However, it is possible to run an Intrinsic Reaction co-ordinate which follows the minimum energy pathway from a transition state down to the minimum energy product on the potential energy surface. Prior to this, an estimate of the conformation of the local energy minima will be made, by direct comparison of the geometries of the HF-optimised transition states with the geometries of the ten HF-optimised conformations of 1,5- Hexadiene.

IRC Analysis for the Chair conformation

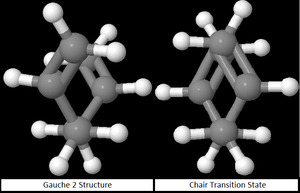

Taking into consideration all the possible conformations of 1,5- Hexadiene, it can be seen (below) that the HF-optimised structure of the chair transition state strongly resembles the HF-optimised Gauche 2 conformer.

Initial 50 Step Optimisation:

The IRC calculation was setup so that it was able to compute 50 points along the pathway relating to the collapse of the chair transition state, in the forward direction only. The resulting structure that was returned from this calculation is shown as a 3D Jmol in the link provided. The LOG file for this calculation is also provided in the references. [30]

A summary of results for the output structure of this calculation is shown in the table below:

| Total Energy/Ha | RMS Gradient | Number of Intermediates |

|---|---|---|

| -231.68514 | 1.33637x10-3 | 21 |

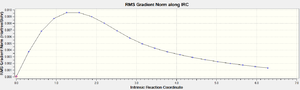

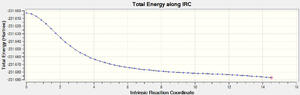

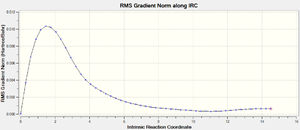

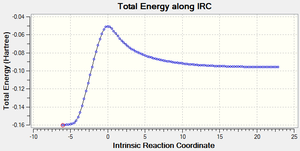

Two graphs produced from the IRC calculation are shown below. Figure 13 depicts the variance of Total Energy versus the Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate.

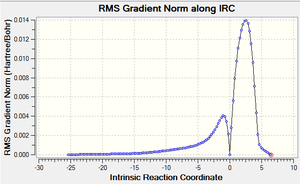

Figure 14 depicts the variance of the RMS Gradient versus the Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate.

There is a large disparity between the values of Total Energy for the resulting IRC structure and the total energy of the HF-optimised Gauche 2 structure. This indicates that the optimisation calculation is not entirely complete. Three separate methods were used to complete this calculation:

i) The optimisation was repeated, but this time producing 100 data points along the reaction pathway, as opposed to 50.

ii) The optimisation was repeated, but this time re-calculating the force constant at every step.

iii) A HF/3-21G optimisation was performed on the structure corresponding to the final data point on the graphs (Structure 21)

i) 100 Step Optimisation:

The IRC calculation was performed again, but this time computing 100 data points instead of 50, but yielded exactly the same results as the 50 step IRC Optimisation:

| Total Energy/Ha | RMS Gradient | Number of Intermediates |

|---|---|---|

| -231.68514 | 1.33637x10-3 | 21 |

This is highly unsurprising, as the position of the initial and, more importantly, the final data points will remain unchanged. The difference between the two methods would be in the general shape of the curve, as having more data points allows a plot of greater accuracy to be produced. The structure produced from this IRC Optimisation is shown in the link provided. [31]

Only the table of results will be shown however, as the Graphs look exactly the same as those for the 50-point structure.

ii) 50 Step Optimisation, calculating Force constants at each step:

The optimsation was repeated again, this time calculating the force constants at every step, which produced the following structure [32]. What was most interesting about these results was that the optimisation went through 47 intermediates, which is over twice as many as that IRC calculations that only calculated the force constants once. The results summary for this IRC calculation is shown below:

| Total Energy/Ha | RMS Gradient | Number of Intermediates |

|---|---|---|

| -231.69166 | 1.143x10-5 | 47 |

Aside from the increased number of intermediates produced, it is also apparent that the value for the RMS Gradient has decreased by approximately two orders of magnitude. This suggests that the geometry has been optimised to a greater extent than it was for the two previous IRC optimisations.

Most importantly, the difference in 'Total Energy' between the HF-optimised Gauche 2 conformer and the structure resulting from this calculation is only 0.00001Ha = 0.006kcal mol-1.

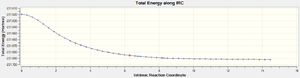

Two graphs produced from the IRC calculation are shown below. Figure 15 depicts the variance of Total Energy versus the Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate.

Figure 16 depicts the variance of the RMS Gradient versus the Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate.

iii) Standard Optimisation from Final Intermediate of 50 IRC method:

The final optimisation required the structure corresponding to the final data point to undergo a normal HF/3-21G energy optimisation. The resulting structure from this method is shown in the following link[33], with the LOG file shown in the references.

The Energetic data retrieved from the Summary file is shown below:

| Total Energy/Ha | RMS Gradient |

|---|---|

| -231.69167 | 5.96x10-6 |

The produced value for the RMS Gradient is the lowest of the three further optimisation methods used in the IRC analysis. This suggests that the geometry has been optimised to an even greater extent than it was for the three previous IRC optimisations. Even more importantly is that the value of Total Energy for the system corresponds exactly (to 5 d.p) to the Total Energy for the Gauche 2 conformer, thereby confirming it as the product of the Cope Rearrangement.

IRC Analysis for the Boat conformation

The same analysis was to be performed for the boat conformation of the transition state. Taking into consideration all the possible conformations of 1,5- Hexadiene, it can be seen (below) that the HF-optimised structure of the boat transition state strongly resembles the HF-optimised Gauche 3 conformer.

From the previous section it was determined that either the direct IRC calculation, in which the force constants were always calculated, or the IRC calculation to 50 points, followed by a subsequent HF/3-21G optimisation were the best methods to obtain an energy close to the expected energy of the product molecule. The 'always calculating force constant method' was chosen for analysis of this transition state.

50 Step (Always calculate Force Constant) Optimisation for Boat:

This IRC optimisation yielded the following structure[34], which, discounting the obscure ladder style bond, strongly resembles the Gauche 3 conformer. Unfortunately, the data for the 'Total Energy' extracted from the summary (shown below) does not agree with the predicted reaction products. This might be due to an error int he optimisation of the boat transition state.

| Total Energy/Ha | RMS Gradient | Number of Intermediates |

|---|---|---|

| -231.68726 | 6.521x10-4 | 51 |

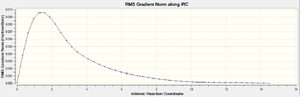

Further evidence of an error within the structure that could have caused the Total Energy to differ from the expected product can be found in the IRC graphs (below). Note the general shape of the RMS graph in the region around IRC = 11. It appears the calculation found a minimum point in this region and then 'bounced' back upwards. This should not have occurred.

Figure 18 depicts the variance of Total Energy versus the Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate.

Figure 19 depicts the variance of the RMS Gradient versus the Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate.

Activation Energy of the Chair and Boat Transition states

Both the Chair[35] and Boat[36] Transition Structures were subjected to optimisation at the DFT level of theory, so as to provide a more accurate geometrical structure and prediction of Total Energy.

The activation energies of both the transition states were calculated at both the DFT B3LYP/6-31G* and HF/3-21G levels. Furthermore, the activation energies of both transition states were calculated at two different temperatures; room temperature (298.15K) and absolute zero (0.00K, although, this had to be simulated as 0.0001K to allow the calculation to run).

Activation energies (at 298.15K) were calculated by subtracting the Sum of the Electronic and Thermal Energies for the product molecule from the Sum of the Electronic and Thermal Energies for the appropriate transition state.

Activation energies (at 0.00K) were calculated by subtracting the Sum of the Electronic and Zero point Energies for the product molecule from the Sum of the Electronic and Zero point Energies for the appropriate transition state.

The 'product molecule' was determined to be the lowest energy conformation of 1,5- Hexadiene at that level of optimisation.

| Transition State | Point Group | Total Energy (HF/3-21G Method)/Ha | Σ(Electronic and Zero Point Energies) at 0.00K (HF/3-21G Method)/Ha | Σ(Electronic and Thermal Energies) at 298.15K (HF/3-21G Method)/Ha | Activation Energya at 298.15K (HF/3-21G Method)/kcal mol-1 | Activation Energya at 0.00K (HF/3-21G Method)/kcal mol-1 | Total Energy (DFT B3LYP/6-31G*)/Ha | Σ(Electronic and Zero Point Energies) at 0.00K (DFT B3LYP/6-31G*)/Ha | Σ(Electronic and Thermal Energies) at 298.15K (DFT B3LYP/6-31G*)/Ha | Activation Energyb at 298.15K (DFT B3LYP/6-31G*)/kcal mol-1 | Activation Energyb at 0.00K (DFT B3LYP/6-31G*)/kcal mol-1 | Literature Activation Energy [0K]/kcal mol-1[37] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chair | C2h | -231.61932 | -231.46622 | -231.46669 | 41.39 | 44.87 | -234.55448 | -234.41119 | -234.40518 | 35.64 | 36.20 | 33.5±0.5 |

| Boat | C2v | -231.60280 | -231.45095 | -231.45093 | 51.28 | 54.16 | -234.54045 | -234.39805 | -234.39257 | 43.55 | 44.44 | 44.7±2.0 |

a Activation Energy relative to the Gauche 3 conformation [Energetically Lowest Conformation under HF/3-21G analysis]

b Activation Energy relative to the Anti 1 conformation [Energetically Lowest Conformation under DFT B3LYP/6-31G* analysis]

It can clearly be seen that the activation energies calculated at the higher level of optimisation (DFT) are closer to the stated literature values. This demonstrates that lower level methods, such as the primitive Hartree-Fock method, are unsuited to determining activation energies accurately.

The activation energies determined at the DFT level of theory can be said to agree with the literature, especially for the boat conformation, which was only 0.26kcalmol-1 off the literature value, well within the stated error limits of ±2.0kcalmol-1.

Cope Rearrangement Conclusion

This section of the Module has introduced a variety of techniques that can be utilised in the construction of transition states for pericyclic reactions. Once constructed, we can probe the structure and relative energies of these transition states, as shown with the Cope Rearrangement of 1,5- Hexadiene.

Out of the three methods used in the construction of the transition states, the Redundant co-ordinate method was found to be the most useful. It appeared that the QTS2 method was unable to correctly optimise the boat transition state, so that effective IRC analysis could be performed (this could explain the origin of the 'bump' in the RMS Gradient vs. IRC graph). Furthermore, this method easily required the most care in setting up. The direct calculation of the Hessian matrix was the simplest to set up, but has a greater margin of error associated with it, particularly for larger molecules (for which the calculation can also be incredibly time consuming to perform, if the reaction co-ordinates are not frozen).

Furthermore, when performing IRC analysis on transition states, re-calculating the force constant at every step (for 50 steps) seemed to produce results which are more concordant with the expected values, when compared to only calculating the force constants once for the same number of steps. It was also seen that performing a standard HF/3-21G optimisation after the initial 50 step optimisation yielded highly accurate values of energy, with respect to the expected products.

Finally, and somewhat predictably, the higher level optimisation method (DFT-B3LYP/6-31G*) produced values of Activation Energy closer to the literature values than the lower level optimisation method (HF/3-21G).

Several of these inferences will be utilised in the following section, such as the decision as to which transition state optimisation method should be used in the optimisation of the Diels-Alder transition state, or which IRC method to use when analysing the collapse of two conformationally different transition states into their respective products.

Diels Alder Cycloaddition Investigation

Introduction

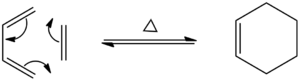

The second part of this module demonstrates the use of computational methods in determining the structures of the transition states of cycloaddition reactions (as opposed to the sigmatropic rearrangement reaction analysed previously), in particular, the classic Diels-Alder reaction. The Diels-Alder reaction is defined as a π4s + π2s cycloaddition reaction, in which the π-orbitals of a (typically electron poor) dienophile species interact with the π-orbitals of a (typically electron rich) conjugated diene. This interaction results in the formation of two new σ bonds between the two species. The reaction is known to occur in a concerted fashion, via a single transition state. An example of a Diels-Alder reaction, the formation of Cyclohexene, is shown below:

During this module, two specific reactions will be subjected to computational analysis:

1) The π4s + π2s cycloaddition reaction between cis- Butadiene and Ethene.

2) the π4s + π2s cycloaddition reaction between Cyclohexadiene and Maleic Anhydide

The first reaction will act as an example in the modelling of transition states in Gaussview 5.0, and will also demonstrate the differences between geometry optimisations and energy minimisations using two different levels of theory, the semi- empirical AM1 method and the more comprehensive DFT B3LYP/6-31G* method.

The second reaction will demonstrate the application of the techniques shown previously in this module on a more complex Diels-Alder reaction. The use of the Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate method will also be shown in the analysis of the exo- and endo- forms of the transition state.

Molecular Orbital and Vibrational analysis will be performed on the transition states of both reactions.

Investigation into the Cycloaddition Reactants: Ethene and cis- Butadiene

Prior to the analysis of the transition state in the cycloaddition reaction between cis- Butadiene and Ethene, an optimisation calculation must be performed on the reactants. Both of the reactants were drawn on the GaussView 5.0 program, and the level of optimisation set was the semi-empirical AM1 method. This method is more accurate than the Hartree-Fock methods used in the previous section, but less accurate than the DFT-B3LYP/6-31G* method, which will be used at a later stage for advanced optimisation calculations. It was deemed unnecessary to use such an advanced (and time consuming) method on what is, primarily, the optimisation of two simple molecules.

The values for Total Energy and RMS Gradient have been extracted from the summaries for each of the optimised reactants. Furthermore, the optimised structures for both reactants can be seen as Jmol images by clicking on the appropriate link in the table below.

| Reactant (Please click for 3D Jmol Image) | Total Energy/Ha | RMS Gradient |

|---|---|---|

| cis- Butadiene [38] | 0.04880 | 1.489x10-5 |

| Ethene [39] | 0.0300 | 0.00 |

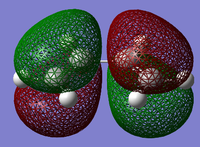

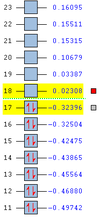

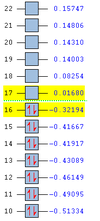

The structure of the Frontier Molecular Orbitals (MO's) that will participate in the Diels-Alder cycloaddition can also be extracted from the results of the AM1 optimisation calculation. Images of the Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital (HOMO) and Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital (LUMO), along with a Figure depicting the relative energies of the MO's for each reactant are shown in the Table below.

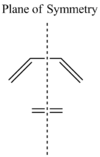

The symmetry of each of the MO's shown in the table, with respect to the plane of symmetry shown below, has also been determined.

For the Diels-Alder rcycloadditon eaction to occur, the HOMO of the diene must be able to interact with the LUMO of the dienophile. It is known that only MO's of the same symmetry can interact with each other. The table above shows that both the HOMO of the diene and the LUMO of the dienophile are both Anti-Symmetric with respect to the plane, thereby allowing an energetically favourable interaction to occur between them.

Investigation into the Cycloaddition of Ethylene and cis- Butadiene Transition State

The cyclic transition state was constructed through the use of the Frozen co-ordinate method, which was explored earlier in the Module. Firstly, the AM1-optimised structures of cis- Butadiene and Ethene were placed together in a Molecule group on GaussView 5.0. The geometry of the Ethene molecule was altered, so that it ended up in an 'envelope-like' form with respect to the cis- Butadiene molecule. The interatomic distance between the terminal carbon atoms of the diene and the carbon atoms of the Ethene was set to 2.2Å. The co-ordinates between these two sets of atoms were then frozen, and standard AM1 optimisation was performed. The co-ordinates of the resulting structure[40] were then unfrozen and set to calculate a derivative, and the molecule was optimised to a transition state using the normal Hessian method.

So as to provide a comparison between optimisation methods, a further, higher level DFT-B3LYP/6-31G* optimisation was performed on the transition state. Please note: Jmol images and the LOG file references for both of the transition state structures are given in the Frequency analysis table, below:

A frequency analysis of the transition state at both levels of optimisation was performed, to determine whethern the structures had actually been optimised to a transition state (thereby producing a negative vibrational mode along the reaction pathway) or whether it had been merely optimised to a minimum (in which no negative vibrational modes would be produced).

The predicted IR spectra from both optimisation methods are shown below:

IR Spectrum of the AM1 optimised structure of the transition state:

IR Spectrum of the DFT-B3LYP/6-31G* optimised structure of the transition state:

There are several differences to note between the two spectra shown above.

- The DFT-optimised transition state appears to have fewer C-H stretching modes (3200-3400cm-1) than the AM1-optimised transition state.

- However, the spectra for the DFT-optimised structure seems to contain a greater number of C-H bending modes(1200cm-1).

- There are two clear peaks in the C=C stretching region for the AM1-optimised structure, whilst there are three clear peaks in the same region for the DFT-optimised structure.

The stretching frequencies for the imaginary modes of vibration, along with their corresponding intensities, are documented in the table (below). The Energy, RMS Gradient and Point Group for each of the transition structures is also shown in the table.

| Transition State | Point Group | Total Energy/Ha | RMS Gradient | Frequency of Imaginary Mode/cm-1 [Intensity] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AM1 Optimised [41] | Cs | 0.11165 | 1.618x10-4 | -951 [5.80] |

| DFT B3LYP/6-31G* Optimised [42] | Cs | -234.54390 | 3.841x10-5 | -524 [5.80] |

An animation of the imaginary vibrational mode for the AM1 optimised structure is shown below:

NOTE: PLEASE CLICK ON THE IMAGE, THEN THE IMAGE IN THE PAGE YOU'RE REDIRECTED TO, TO VIEW THE ANIMATION

An animation of the imaginary vibrational mode for the DFT optimised structure is shown below:

NOTE: PLEASE CLICK ON THE IMAGE, THEN THE IMAGE IN THE PAGE YOU'RE REDIRECTED TO, TO VIEW THE ANIMATION

An animation of the lowest positive vibrational mode (136cm-1, Intensity: 0.72) for the DFT optimised structure is shown below:

NOTE: PLEASE CLICK ON THE IMAGE, THEN THE IMAGE IN THE PAGE YOU'RE REDIRECTED TO, TO VIEW THE ANIMATION

Each of the bond lengths within the transition state have been recorded, and compared to the literature[43] values.

| Transition State | Forming C-C Bond Separation/Å | Diene C=C Bond Length/Å [Lit: 1.33] | Diene C-C Bond Length/Å [Lit: 1.53] | Ethene C=C Bond Length/Å [Lit: 1.33] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AM1 Optimised | 2.12 | 1.38 | 1.40 | 1.38 |

| DFT B3LYP/6-31G* Optimised | 2.27 | 1.38 | 1.41 | 1.39 |

Vibrational Analysis: The presence of an imaginary vibrational mode in both vibrational spectra proves that both structures have been optimised to a transition state, as opposed to a minima. This imaginary vibrational mode shows the constituent molecules that make up the transition state vibrating along the reaction co-ordinate in a synchronous [concerted] manner (this makes sense, as pericyclic reactions do not have a 'beginning' or 'end'), this is in direct agreement with what was stated in the introduction.

The lowest real vibrational mode was the rotation of the diene with respect to the Ethene, with the Ethene itself rotating in the opposite direction [in an asynchronous manner](thereby lengthening one of the implicit C-C 'bonds', and shortening the other at the same time.)

Bond Length Analysis: For both the AM1 and DFT-optimised transition states, it was found that the C-C and C=C bond lengths in the diene were approximately equal (1.38-1.41Å). This may initially seem surprising, as the literature suggests that the C-C bonds should be longer and the C=C bonds should be shorter. The discrepancy between the literature and the experimental results can be explained by invoking the concept of 'conjugation'. The electron density situated in the π-orbtials is not localised to the two terminal C=C bonds (as the skeletal structure would suggest), it is delocalised over the four carbon system. This results in approximately equivalent bond lengths between the carbons.

The major difference between the two structures resides in the non-bonding carbon atoms (that will break/form a bond when the transition state collapses). For non-bonded atoms, one would expect the separation between the two carbon atoms to be double the value of the Van der Waals radii of carbon (2x1.70Å)[44]. the fact that, for both structures, the interatomic distance is far lower than this demonstrates that there is some form of a bonding interaction between the diene and the dienophile. It was also noted that the interatomic distance between the two 'bonding' carbons was greater for the higher level optimisation method, it is possible that the lower level semi-empirical method could not take account of some particular repulsive interaction, which the DFT-method did, thus increasing the distance to lower the energy of the system.

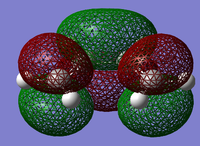

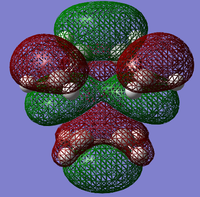

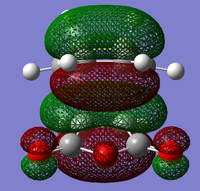

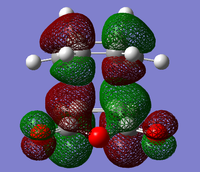

MO Analysis for Transition State

The MO's obtained from the optimisation calculations (using both the AM1 and the DFT-B3YLP/6-31G* Methods) for the transition state are shown in the table below. As with before, the symmetries of the MO's, with respect to the plane of symmetry shown earlier, has been stated in the table.

By directly comparing the MO's of the transition state with those produced for the reactants, it is possible to determine the fragment orbital contribution to each of the Molecular orbitals shown above.

Ψ(AM1-optimised HOMO) = cΨ(cis- Butadiene HOMO) - cΨ(Ethene LUMO)

Ψ(AM1-optimised LUMO) = cΨ(Ethene HOMO) + cΨ(cis- Butadiene LUMO)

Ψ(DFT-optimised HOMO) = cΨ(Ethene HOMO) - cΨ(cis- Butadiene LUMO)

Ψ(DFT-optimised LUMO) = cΨ(Ethene HOMO) + cΨ(cis- Butadiene LUMO)

Where 'c' is a constant that accounts for the relative contribution from each Fragment Orbital (FO) to the MO.

By observing the relative positions of the energy levels for each method of optimisation, it becomes clear as to why there is a difference in structure between the two HOMO's produced by the different methods. For the DFT optimised transition state, the HOMO is the second highest bonding molecular orbital in the system, whereas the HOMO is the highest bonding orbital in the system for the AM1 method. It would, therefore, make sense for the different HOMO's to arise from different combinations of fragment orbitals. Both of the LUMO's show significant mixing between orbitals from the different fragments. This creates a 'shared' region of electron density between the two fragments. The most important molecular orbital arising from these calculations, however, is the AM1-optimised HOMO. This is formed from the overlap of the cis- Butadiene π-orbital with the Ethene π* orbital, which results in the two sigma bonds being formed between the diene and the dieneophile. it is the population of this MO which allows the reaction to occur.

Computational Analysis of the Reactants of the Maleic Anhydride + Cyclohexadiene cycloadditon

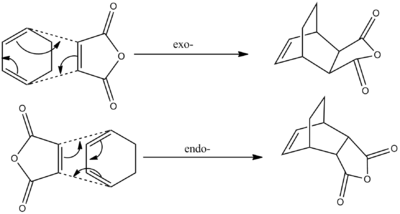

The Diels-Alder reaction between Maleic Anhydride and Cyclohexadiene can result in the formation of one of two products. Performing this reaction under kinetic control (such as low temperatures and short reaction times) would result in the endo- product being formed almost exclusively. However, if you increase the temperature of the reaction vessel, and leave the reaction for a longer period of time, the equilibrium shifts to favour the thermodynamic, exo- product. The endo- product is considered the kinetic product due to the stablising secondary orbital interactions present in the transition state, thereby lowering the energy of the transition state relative that of the exo- approach. However, the exo- product is of a lower total energy than the endo- product, due to the greater degree of stearic strain within the latter.[45]

A reaction scheme is shown in Figure 32 below:

The aim of this third part of the module is to model both the endo- and exo- transition states for the reaction of Maleic Anhydride with Cyclohexadiene, and attempt to rationalise the kinetic preference for the endo- product over the exo- product.

As with the previous cycloaddition reaction, the reactants need to be modelled and optimised before any transition state analysis can be performed. Both reactants were drawn on GaussView 5.0 and were optimised to a minimum using the semi-empirical AM1 method. the following data was obtained from the results summaries:

| Reactant | Point Group | Total Energy/Ha | RMS Gradient |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maleic Anhydride [46] | C2v | -0.12182 | 3.683x10-5 |

| Cyclohexadiene [47] | C2 | 0.02771 | 5.62x10-6 |

As with the previous cycloaddition reaction, the HOMO's and LUMO's of the reactants have been visualised, and their symmetries (with respect to the plane shown previously) have been determined and are shown in the table below.

Computational Analysis of the Transition State of the Maleic Anhydride + Cyclohexadiene cycloaddition

The transition state for Diels-Alder reaction under consideration was constructed through the use of the Frozen co-ordinate method, as with the cycloaddtion reaction for cis- Butadiene and Ethene. The AM1- optimised structures of both of the reactant molecules were arranged in a manner similar to that of the expected product molecule for both the exo- and endo- transition states. The interatomic distance between the two sets of Frozen co-ordinates was set to 2.2Å. A semi-empirical AM1-optimisation was performed on both of the structures. The co-ordinates of the resulting structures[48],[49] were then unfrozen and set to calculate a derivative, the molecule was subsequently optimised to a transition state using the normal Hessian method.

As with the previous Diels-Alder reaction, a comparison between the semi-empirical AM1 optimisation method and the DFT-B3LYP/6-31G* method will be provided. The resulting transition structures were subsequently optimised to the DFT-level.

The results of both levels of optimisation to the transition states are shown in the Table below:

| Transition State (Please click for 3D Jmol Image) | Point Group | Total Energy /Ha | RMS Gradient |

|---|---|---|---|

| endo- (AM1) [50] | Cs | -0.05150 | 2.354x10-5 |

| endo- (DFT) [51] | Cs | -612.75829 | 2.322x10-5 |

| exo- (AM1) [52] | Cs | -0.05042 | 7.03x10-5 |

| exo- (DFT) [53] | Cs | -612.75579 | 2.792x10-5 |

From these results it can be seen that the endo- is the more stable of the two transition states at both levels of optimisation. This is in agreement with the discussion provided in the introduction section. However, this data does not provide any sort of explanation as to why the endo- transition state is the more stable of the two, this will be discussed in the MO section of the exercise.

A frequency analysis will be performed to ensure that both structures produced are actually transition states, as opposed to minima.

The IR spectrum of the AM1- optimised exo- transition state is shown in Figure 37 below.

The data for the imaginary frequencies for both transition states (optimised to AM1 only) is given in the table below. Furthermore, the frequency of the lowest positive vibrational mode after the imaginary frequency is also provided in the table.

| Transition State | Imaginary Vibrational Frequency/cm-1 [Intensity] | Lowest positive Vibrational Frequency/cm-1 [Intensity] |

|---|---|---|

| endo- | -807 [71.43] | 63 [1.54] |

| exo- | -811 [97.16] | 60 [0.56] |

The presence of negative vibrational modes for both transition states confirms that they have both been successfully optimised to transition structures, as opposed to minima or points of inflection.

An animation of the negative vibrational mode for the exo- transition state (when optimised using the AM1 level of theory) has been produced (below:)

NOTE: PLEASE CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO VIEW THE ANIMATION

This mode shows us vibration along the path of the transition state, in a concerted manner.

An animation of the negative vibrational mode for the endo- transition state (when optimised using the AM1 level of theory) has been produced (below:)

As with the exo-, this mode shows us vibration along the path of the transition state, in a concerted manner.

An animation of the first positive vibrational mode for the exo- transition state (when optimised using the AM1 level of theory) has also been produced (below), so as to provide a direct comparison with the equivalent mode in cis- Butadiene Diels-Alder reaction.

This mode shows us the rotation of the Cyclohexadiene group in the opposite direction to the rotation of the Maleic Anhydride ring in an asynchronous manner, as was the case with the lowest positive frequency in the Diels-Alder reaction between cis- Butadiene and Ethene.

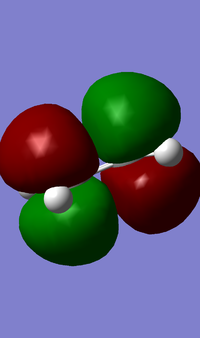

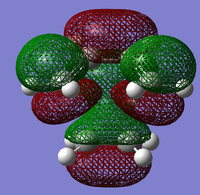

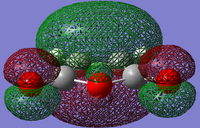

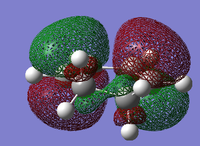

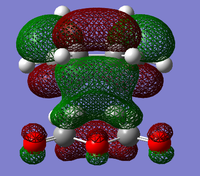

Transition State MO analysis

The structures of several MO's for the exo- and endo- (AM1-optimised) transition states were determined using the GaussView 5.0 program. It was decided that, in addition to the HOMO and the LUMO which were exclusively determined for the previous reaction, the structure of the HOMO-1 and LUMO+1 MO's would also be visualised, so as to gain a greater insight into the nature of the bonding/anti-bonding interactions that contribute to the overall stability of the transition state. In particular, visualising more than two Molecular Orbtials would increase the probability of finding the MO that causes the secondary orbital interaction that is responsible for the lowering of the overall energy of the endo- transition state with respect to the exo-.

The following calculations will show the fragment orbital contributions to the overall molecular orbitals of the transition state. These calculations were able to be estimated as they have to conform to strict rules, in particular, only orbitals of the same symmetry can interact, therefore, it would be impossible to get the LUMO of Maleic Anhydride to interact with the LUMO of Cyclohexadiene, as they are both of different symmetries.

Ψ(endo- HOMO-1) = cΨ(Maleic Anhydride HOMO) + cΨ(Cyclohexadiene LUMO)

Ψ(endo- HOMO) = cΨ(Maleic Anhydride LUMO) - cΨ(Cyclohexadiene HOMO)

Ψ(endo- LUMO) = cΨ(Maleic Anhydride LUMO) + cΨ(Cyclohexadiene HOMO)

Ψ(endo- LUMO+1) = cΨ(Maleic Anhydride HOMO) - cΨ(Cyclohexadiene LUMO) [Mixing Contribution]

Ψ(exo- HOMO-1) = cΨ(Maleic Anhydride HOMO) + cΨ(Cyclohexadiene LUMO)

Ψ(exo- HOMO) = - cΨ(Maleic Anhydride LUMO) - cΨ(Cyclohexadiene HOMO)

Ψ(exo- LUMO) = cΨ(Maleic Anhydride LUMO) - cΨ(Cyclohexadiene HOMO)

Ψ(exo- LUMO+1) = cΨ(Maleic Anhydride HOMO) + cΨ(Cyclohexadiene LUMO) [Mixing Contribution]

Where 'c' is a constant that accounts for the relative contribution from each Fragment Orbital (FO) to the MO.

The orbital(s) involved in mixing cannot be determined by such a simple method, to estimate this, a full MO diagram would have to be produced.

It can be seen (from both the front, and the side view) that the LUMO+1 MO is the origin of this secondary orbital interaction. The LUMO of the Cyclohexadiene interacts with the orbitals of the carbonyl groups on the Anhydride moiety. Comparison of the 'side view' diagrams between the endo- and exo- transition state confirm this. Unlike the exo- transition state, the endo- transition state is of the correct orientation and symmetry to interact with these orbitals.

Bond Length Analysis

The table below contains all the relevant bond lengths and interatomic distances for the two transition states of this reaction, optimised at the two different levels of theory. Note that 'relative orientation' is distance between the carbonyl carbon atoms and:

"the carbon atoms of the “opposite” -CH2-CH2- for the exo and the “opposite” -CH=CH- for the endo"[54] [quoted from the wiki]

| Transition State | Forming C-C Bond Separation/Å | Cyclic Diene C=C Bond Length/Å | Cyclic Diene C-C Bond Length/Å | Maleic Anhydride C=C Bond Length/Å | Maleic Anhydride C=O Bond Length/Å | Relative Orientation/Å |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AM1 Optimised (exo-) | 2.17 | 1.39 | 1.40 | 1.41 | 1.22 | 2.95 |

| DFT B3LYP/6-31G* Optimised (exo-) | 1.56 | 1.51 | 1.34 | 1.54 | 1.20 | 2.98 |

| AM1 Optimised (endo-) | 2.16 | 1.39 | 1.40 | 1.41 | 1.22 | 2.89 |

| DFT B3LYP/6-31G* Optimised (endo-) | 1.56 | 1.51 | 1.34 | 1.54 | 1.20 | 2.99 |

For the DFT-optimised transition states, there does not appear to be much difference at all between the endo- and the exo- product. The same can be said of the two AM1-optimised structures, with the notable exception of the relative orientation, which differs between the endo- and exo- form by 0.06Å.

What is interesting, however, is the differences between the bond lengths from the AM1-optimised structures and the DFT-optimised structures. The DFT calculation seems to have effectively optimised the bond lengths so that they correspond to the literature values [1.33 for C=C, 1.53 for C-C][55]. It is also interesting to note that the DFT calculation effectively treats the reaction as 'complete' even though it's in the transition state. [By treating it as complete, I mean that it approximates the C-C bond in the centre of the diene as if it were C=C bond, and the C=C bonds that made up the diene system as C-C bonds, which equates to the product molecule.] The DFT calculation appears to treat both isomers as if they were products and not transition states.

IRC Analysis of Diels Alder reaction

An intrinsic reaction co-ordinate calculation was run on both the exo- and endo- transition states. The calculation was set up so that 100 data points were plotted in both the forwards and reverse directions, always recalculating the force constant at each step. This will enable us to view the full reaction profile, from reactants to the product molecule. We can also use this as a 'check' of how well our transition state has been optimised.

Table 21 below, contains the data obtained from the IRC calculations, whilst Table 22, below that, contains the data obtained from the AM1 optimisations of the final products. An analysis of both of these sets of data will be presented after the second table.

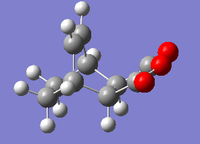

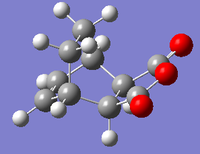

| Property | endo- IRC Transition State [56] | exo- IRC Transition State [57] |

|---|---|---|

| Structure of the final data point |  |

|

| Forwards and Backwards Total Energy vs. IRC plot |  |

|

| Total Energy of Final data point/Ha | -0.16017 | -0.15991 |

| Forwards and Backwards RMS gradient vs. IRC plot |  |

|

| RMS Gradient of Final data point | 1.867x10-5 | 2.368x10-5 |

| C-C bond Forming interatomic distance/Å | 1.54 | 1.54 |

| Total number of intermediates | 124 | 110 |

| Property | endo- final product [58] | exo- final product [59] |

|---|---|---|

| Image |  |

|

| Total Energy/Ha | -0.16017 | -0.15991 |

| RMS Gradient | 1.440x10-5 | 6.516x10-5 |

| 'new' C-C bond length/Å | 1.54 | 1.54 |

There are several inferences to be made from this data. Firstly, the interatomic distance between the non-bonded carbons (in the final points of the IRC graphs) is the same as the bond length for the newly bonded carbons in both optimised products (1.54Å). This strongly indicates that both transition states collapsed into their respective products successfully. Further evidence of this can be seen by comparing the values obtained for total energy for both the structures corresponding final points on the IRC graphs [endo: -0.16017Ha, exo:-0.15991Ha] with the values of total energy determined for the appropriate AM1 optimised products [endo product: -0.16017Ha, exo product:-0.15991Ha]. It was found that both sets of values corresponded to each other exactly (to 5 d.p).

However, there was one major issue resulting from the IRC and product optimisation calculations, specifically, the endo- product is apparently lower in energy than the exo- product. This is goes completely against the expected results, obtained from the literature, which stated that the exo- product is the thermodynamic product, and should therefore be lower in energy than the endo- product. However, this is clearly not the case, most likely due to the stearic repulsions between the bulky acid anhydride group and the bridging -CH2CH2- Hydrogens, as shown in the diagram below. These repulsions ensure that the exo- product is greater in energy than the endo- product.

Therefore, the endo- product is both the most kinetically and thermodynamically favourable product.

It was also noted that, for some reason, the reaction coordinate seems to go backwards for the exo- product.

Conclusion

This section has demonstrated the effectiveness of computational methods in the modelling of transition states for pericyclic reactions. This is possibly the main advantage of using computational methods on the whole. Transition states are known the have incredibly short lifetimes (in the order of femtosconds)[60], therefore making them impossible to view using conventional spectroscopic techniques. Prior to the advent of computational methods, we could only use the best guess 'Hammond Postulate' to estimate the structure of the transition state. Computational methods have also proven useful in predicting the relative stability of the product molecules from the Diels-Alder reaction with Maleic Anhydride. The energetic analysis of the transition states and the products they collapse into has shown that the literature is not always entirely correct. The literature predicted that the exo- product was the most thermodynamically stable product, however, the computational analysis performed suggested the opposite, that the endo- isomer was both the kinetic and the thermodynamic product.

For the reaction of Maleic Anhydride with Cyclohexadiene, the greater kinetic stability of the endo- transition state with respect to the exo- was rationalised by determining the structures of the Molecular Orbitals associated with the transition state. This allowed us to 'view' the secondary orbital effects which were only alluded to in the literature.

Furthermore, it was shown that lower level methods, such as the semi-empirical AM1 method were satisfactory in determining the structure of the transition state, however, a higher level method, such as the DFT-B3YLP/6-31G*, would be required when determining bond lengths and interatomic distances in transition structures accurately. It was also shown that there is a large discrepancy in the values of the imaginary 'reaction pathway' frequency when using frequency analysis with both the AM1 and DFT methods.

References

- ↑ M. Dewar, Chem. Phys. Lett., 1987, 141, pp.521-524

- ↑ Maluendes et al., J. Chem. Phys., 1990, 93, pp. 5902-5911

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11073

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11074

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11075

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11076

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11077

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11078

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11079

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11080

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11081

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11082

- ↑ H. Rzepa, 2nd Year Conformational Analysis Course, 2011, p. 'Alkanes', http://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/local/organic/conf/

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11083

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11084

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11085

- ↑ J. Coates, Encyclopaedia of Analytical Chemistry, R. A. Meyers (Ed.), 2000, pp. 10815-10831

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11086

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11087

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11088

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11318

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11319

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11320

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11152

- ↑ 3rd Year Computational Laboratory wiki, 2011, https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=Mod:phys3

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11153

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11155

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11157

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11174

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11178

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11178

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11180

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11181

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11182

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11176

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11177

- ↑ 3rd Year Computational Laboratory wiki, 2011, https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=Mod:phys3

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11220

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11221

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11444

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11222

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11223

- ↑ Lide, D., Tetrahedron, 1962, 17, pp.125-134

- ↑ Ü. Muller, Inorganic Strucutral Chemistry, Wiley, 1993, p.31

- ↑ R. Woodward, R. Hoffmann, J. Am Chem. Soc., 87, 1965, pp. 4388-4389

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11296

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11295

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11447

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11448

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11298

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11299

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11297

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11300

- ↑ 3rd Year Computational Chemistry wiki, 2011, https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=Mod:phys3

- ↑ Lide, D., Tetrahedron, 1962, 17, pp.125-134

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11414

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11405

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11407

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11406

- ↑ L. Barter, 3rd Year Molecular Reaction Dynamics Lecture Course, Lecture 2, pp. 1-35