Rep:Mod:msm2

Part 1 - Introduction

Cyclopentadiene

This part investigates the hydrogenation of the cyclopentadiene dimer. This is done by computing the energy of the possible intermediates of the dimer. The total energy of each structure is then compared with each other.

Cyclodimerisation of the cyclopentadiene

Calculations for this part were carried out using the program Avogadro. The molecules were optimised using the MMFF94s force field and conjugate gradients algorithm.

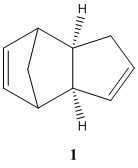

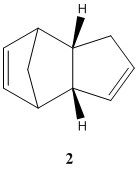

Prior to hydrogenation, the two cyclopentadiene dimerises to form a dimer to give either the exo (molecule 1) or the endo dimer (molecule 2) [1]. Computational shows that the exo product (molecule 1) is the more stable thermodynamic product and this is mostly due to angle bending energy of the endo (molecule 2) being higher. Therefore, the exo product (molecule 1) is the expected product. However, experimentation shows that the endo dimer (molecule 2) is formed rather than the exo dimer (molecule 1). This means that the kinetic product is formed over the thermodynamic product.

The dimerisation of the cyclopentadiene is a π4s + π2s cycloaddition Diels-Alder reaction. It is a concerted reaction which means that it can only form an endo or exo product. In the Diels-Alder reaction, the endo transition state is stabilised by the π-orbitals of the cyclopentadiene rings interacting with each other resulting in the energy of the transition state to be lowered. This interaction is absent in the transition state of the exo configuration and thus the difference in energy of the transition state between the two is great. The lowering of the endo transition state energy reduces the activation energy of the reaction which results in the kinetic product to be the dominant product.

Hydrogenation of cyclopentadiene

Calculations for this part were carried out using the program Avogadro. The molecules were optimised using the MMFF94s force field and conjugate gradients algorithm.

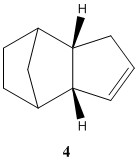

The first hydrogenation across the double bond can be at either end and the two hydrogenated intermediates are analysed to find out which of the two is more likely to occur. Assuming that the end product is the thermodynamic product, molecule 4 is more likely to be produced and will be the dominant product. The total energy difference is huge and the big factor is due to the total angle bending energy between the two structures.

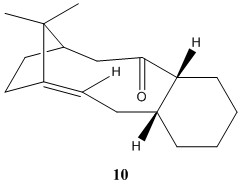

Atropisomerism in an intermediate in the synthesis of taxol - molecule 9 & 10

Atropisomerism occurs when two of the same molecule differs as a result of hindered bond rotation. The hindered bond rotation changes the status of a conformer to a configuration resulting in the isomers to be able to be isolated. This results in the two isomers to have different energy and this effect is investigated with the intermediates in the taxol synthesis.

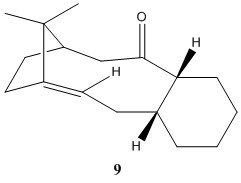

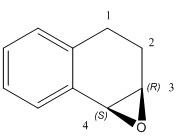

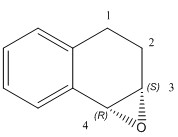

The key intermediate, molecule 9 or 10, in the synthesis of taxol can be synthesised with the oxygen pointing up or down as shown in the picture below. [2] They are not the same structure as there is a large energy barrier for the oxygen to rotate to the other configuration resulting the two molecules to be atropisomers. The table below shows that the structure with the oxygen pointing is lower in energy by about 10 kcal mol-1 and this is largely due to the angle bending energy of the molecule 9 being high.

The increase in energy for molecule 9 could be due to the the fact that the oxygen is pointing up towards all the other groups i.e. the neighboring hydrogen atoms are all pointing up and so is the alkyl group in the side ring. The ring must adopt a certain structure in order to avoid the steric repulsion. By pointing the oxygen down (molecule 10), this releases all the effects experienced by the oxygen as in the previous configuration and therefore molecule being in a lower energy state compared to molecule 9.

By looking at the 3-D structures of both molecule 9 and 10, it can be seen that the 6-membered ring is in the chair position. This is expected as the chair conformation is generally lower in energy compared to the boat/twist-boat conformations.

Subsequent functionalisation of the alkene often results in the reaction rate being unreactive or occur at a much slower rate compared to other alkene. It should firstly be noted that the alkene is located at a bridgehead. According to Bredt's rule, a double bond should not be placed at a bridgehead of a bridged ring system, unless the ring size is large[3]. Since the compound can be isolated, this shows that the ring is large enough to stabilise the strain that would be otherwise felt by the carbon due to the double bond at the bridgehead.

Alkenes with a double bond located a bridgehead is recognised as 'hyperstable olefin'[4]. The term is coined due to this alkene being very unreactive. This is due to the ring having less strain compared to their parent hydrocarbon resulting in the alkene being much more stable than any of its isomers.

Predicting the spectroscopic data using computational chemistry - molecule 17

Optimisation using Avogadro

The molecule was drawn using ChemDraw and then exported to Avogadro to be optimised. The optimisation was done using the MMFF94s force field and conjugate gradients algorithm.

Before the spectroscopic properties can be analysed, the structure was drawn and optimised. The 3-D structure and its energies are tabulated below.

| Molecule 17 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Total energy / kcal mol-1 | 118.10512 | ||||

| Total bond stretching energy / kcal mol-1 | 16.35595 | ||||

| Total angle bending energy / kcal mol-1 | 39.66247 | ||||

| Total torsional energy / kcal mol-1 | 15.74189 | ||||

| Total van der Waals energy / kcal mol-1 | 51.75645 | ||||

| Total electrostatic energy / kcal mol-1 | -7.55957 | ||||

Calculated 1H NMR data

After the optimisation has finished, the structure was subjected to a computational NMR spectroscopy using the following command line:

# B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) Opt SCRF=(CPCM,Solvent=chloroform) Freq NMR EmpiricalDispersion=GD3

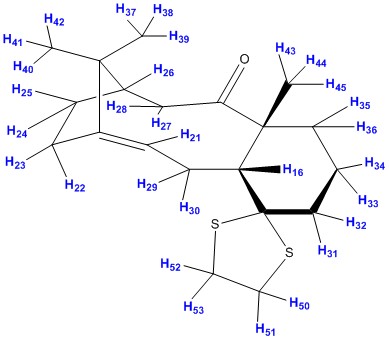

Below is shown the 1H NMR extracted from the output file.

| Molecule 17 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Proton no. | Computed values / ppm DOI:10042/26719 |

Average calculated values / ppm | Literature values / ppm[5] | Degeneracy | Splitting pattern | |

| 21 | 5.88 | 5.88 | 4.84 | 1.00 | dd | |

| 50 | 3.25 | 3.08 - 3.25 | 3.40 - 3.1 | 4.00 | m | |

| 53 | 3.25 | |||||

| 52 | 3.25 | |||||

| 51 | 3.08 | |||||

| 16 | 2.97 | 2.97 | 2.99 | 1.00 | dd | |

| 22 | 3.71 | 1.28 - 3.71 | 1.35 - 2.80 | 14.00 | m | |

| 29 | 3.01 | |||||

| 30 | 2.89 | |||||

| 31 | 2.23 | |||||

| 27 | 2.23 | |||||

| 23 | 2.23 | |||||

| 28 | 2.12 | |||||

| 25 | 1.98 | |||||

| 35 | 1.88 | |||||

| 32 | 1.88 | |||||

| 33 | 1.51 | |||||

| 34 | 1.43 | |||||

| 36 | 1.43 | |||||

| 24 | 1.28 | |||||

| 44 | 2.12 | 1.43 | 1.38 | 3.00 | s | |

| 43 | 1.64 | |||||

| 45 | 0.55 | |||||

| 39 | 1.28 | 0.9 | 1.25 | 3.00 | s | |

| 38 | 0.83 | |||||

| 37 | 0.69 | |||||

| 40 | 1.57 | 1.11 | 1.10 | 3.00 | s | |

| 42 | 1.00 | |||||

| 41 | 0.75 | |||||

| 26 | 2.41 | 2.41 | 1.00 - 0.80 | 3.00 | m | |

First of all, the hydrogen atoms attached to the same carbon are grouped together and the shift values are averaged as this is what actually happens at room temperature; the C-C bond would rotate freely giving the hydrogen atoms the average of all three environments. This would mean that the observed values would be the same as the computed values only if the hydrogens are locked in the same position by lowering the temperature such that the C-C bond rotation is slower than the NMR timescale.

The literature values for the backbone filler hydrogen atoms are grouped together as '14 H' and labelled as 'multiplets'. This is reasonable since all the peaks would coincide at roughly the same shift and the peaks would split multiple times due to neighboring protons. Assigning the peaks would be difficult and would not be beneficial. The range agrees with the computed values.

By looking at the data and comparing them with the literature values, they are actually quite good in terms of ordering and magnitude. Even when they off, it is only up to about 1 ppm. The only one that differs by a large amount is with the hydrogen labelled 26. Computational predicts that this hydrogen is much more deshielded. This is probably due to the hydrogen being close to the oxygen in space. In reality, the hydrogen probably feels lesser of this effect due to hydrogen and oxygen being 2 C-C bonds apart and due to the alkyl group being an electron donating group and therefore shielding the proton more and moves the signal upfield.

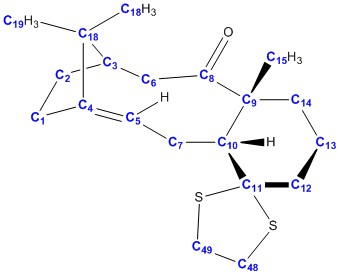

Calculated 13C NMR data

Using the same file as before, the 13C NMR can be invoked. The results are tabulated below and compared with the literature values.

| Molecule 17 | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Carbon no. | Computed values / ppm DOI:10042/26719 |

Literature values / ppm [5] |

| 8 | 219.83 | 218.79 |

| 4 | 149.3 | 144.63 |

| 5 | 117.23 | 125.33 |

| 11 | 93.5 | 72.88 |

| 9 | 62.53 | 56.19 |

| 10 | 58.68 | 52.25 |

| 3 | 55.09 | 48.50 |

| 17 | 53.70 | 46.80 |

| 12 | 50.73 | 45.76 |

| 6 | 49.82 | 39.80 |

| 14 | 46.18 | 38.81 |

| 48, 49 | 43.74 | 35.85 |

| 15 | 36.22 | 32.66 |

| 7 | 31.57 | 28.79 |

| 2 | 30.45 | 26.88 |

| 1 | 26.78 | 25.66 |

| 19 | 26.18 | 23.86 |

| 13 | 25.62 | 20.96 |

| 18 | 22.74 | 18.71 |

In terms of predicting the position of the shifts (ordering of the shifts and the range of where the shift is going to be in), the predicted NMR data was a good match with the literature. There were some errors with the precise numbers of the shifts. This occurs consistently when the carbon is attached/close to an oxygen atom or a heavy element (sulphur).

Part 2 - Analysis of the properties of the synthesised alkene epoxides

The two catalysts - Shi and Jacobsen catalysts

Crystal structure of the Shi pre-catalyst - molecule 21

Molecule 21 is the stable precursor of the active catalyst and therefore can be isolated and stored before use. Crystallography can be used on this structure to determine the crystal structure of this molecule. Using Conquest, the crystal structure of the Shi pre-catalyst can be drawn and then analysed.

|

|

By comparing the O-C-O bond lengths in the Shi pre-catalyst, there are pronounced difference in bond lengths as labelled in the 3-D crystal structure above. One of the C-O bonds is shorter than the other. This is due to the anomeric effect. The antiperiplanar arrangement of the lone pair on the oxygen and the σ* orbital of the C-O triggers this effect for the LPO/σ*C-O conjugation. Since there are 2 oxygen atoms and yet 2 different bond lengths shows that one conjugation is better than the other. This is due to how well the antiperiplanar arrangement is compared to the other. Using the structure above, the lone pair of the oxygen labelled O4 is better in antiperiplanar arrangement with the C-O bond compared to the lone pair of the oxygen O5 with the C-O bond. The lone pair on O4 is better able to donate into the σ* orbital of the C-O bond. Since this is an antibonding orbital, it causes the C-O to lengthen.

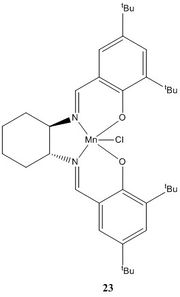

Crystal structure of the Jacobsen pre-catalyst - molecule 23

Molecule 23 is the stable precursor of the active catalyst. It can be isolated and crystallography can be done on this molecule to determine its crystal structure. Using Conquest, the crystal structure of the stable Jacobsen pre-catalyst was drawn and then analysed.

|

|

From the structure above, it is shown that the hydrogen atoms appear close to each other but the distance is more than 2 van der Waals radius of the hydrogen atom. Van der Waals forces of attraction pull these two atoms together.

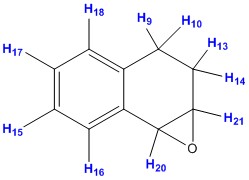

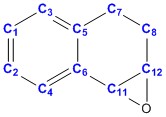

NMR properties of the epoxides - 1,2-dihydronapthalene and trans-β-methyl styrene epoxides

1,2-dihydronapthalene epoxide

Calculated 1H NMR data

| 1,2-dihydronapthalene epoxide 1H NMR | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Proton no. | Computed values DOI:10042/26721 | Average calculated values | Literature values[6] | Degeneracy | Splitting pattern | |

| 16 | 7.61 | 7.25 - 7.61 | 7.09 - 7.41 | 4.00 | m | |

| 17 | 7.39 | |||||

| 15 | 7.39 | |||||

| 18 | 7.25 | |||||

| 20 | 3.56 | 3.56 | 3.85 | 1.00 | m | |

| 21 | 3.48 | 3.48 | 3.73 | 1.00 | m | |

| 9 | 2.95 | 2.95 | 2.76 - 2.82 | 1.00 | m | |

| 10 | 2.27 | 2.27 | 2.53 - 2.57 | 1.00 | m | |

| 14 | 2.21 | 2.21 | 2.40 - 2.43 | 1.00 | m | |

| 13 | 1.87 | 1.87 | 1.74 - 1.80 | 1.00 | m | |

As expected, protons labelled 15, 16, 17 and 18 have shifts in the range 7.2 - 7.6 ppm. This is due to the protons being part of the benzene ring. Proton labelled 20 has shifts at 3.56 ppm and this is due to the proton and the oxygen are attached to the same carbon. Similar observation can be made for proton labelled 21. This results in the protons being more deshielded than the normal alkyl protons, labelled 9, 10, 13 and 14.

Calculated 13C NMR data

| 1,2-dihydronapthalene epoxide 13C NMR | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Carbon no. | Computed values DOI:10042/26721 |

Literature values [7] |

| 5 | 135.39 | 137.1 |

| 6 | 130.37 | 132.9 |

| 4 | 126.67 | 129.9 |

| 1 | 123.79 | 128.83 |

| 3 | 123.53 | 128.80 |

| 2 | 121.74 | 126.5 |

| 12 | 52.82 | 55.5 |

| 11 | 52.19 | 55.2 |

| 7 | 30.18 | 24.8 |

| 8 | 29.06 | 22.2 |

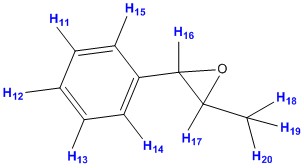

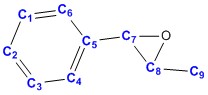

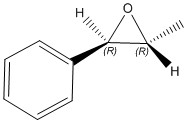

trans-β-methyl styrene epoxide

Calculated 1H NMR data

| β-methyl styrene epoxide 1H NMR | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Proton no. | Computed values DOI:10042/26720 |

Average calculated values | Literature values [7] | Degeneracy | Splitting pattern | |

| 15 | 7.50 | 7.31 - 7.50 | 7.28 - 7.44 | 5.00 | m | |

| 13 | 7.50 | |||||

| 11 | 7.48 | |||||

| 12 | 7.42 | |||||

| 14 | 7.31 | |||||

| 16 | 3.41 | 3.41 | 3.57 | 1.00 | d | |

| 17 | 2.79 | 2.79 | 3.32 - 3.40 | 1.00 | qd | |

| 20 | 1.68 | 1.33 | 1.45 | 3.00 | d | |

| 18 | 1.59 | |||||

| 19 | 0.72 | |||||

| β-methyl styrene epoxide 1H NMR coupling constants | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proton no. | Splitting pattern | Literature coupling constants [7] | Computed coupling constants DOI:10042/26722 | |

| 15 | m | - | - | |

| 13 | ||||

| 11 | ||||

| 12 | ||||

| 14 | ||||

| 16 | d | 4.3 | 1.37 | |

| 17 | qd | - | - | |

| 20 | d | 5.4 | 5.40 | |

| 18 | ||||

| 19 | ||||

The 1H spin coupling constant was also calculated for this structure. The coupling constant was in good match with the literature. For H16, the coupling constant value differs by a value of ~3Hz, this is not too bad considering that the computed coupling constant is accurate for up to 2Hz.

Calculated 13C NMR data

| β-methyl styrene epoxide 13C NMR | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Carbon no. | Computed values DOI:10042/26720 |

Average calculated values | Literature values [7] |

| 5 | 134.98 | 134.98 | 135.84 |

| 3 | 124.07 | 123.7 | 128.3 |

| 1 | 123.33 | ||

| 2 | 122.73 | 122.73 | 127.7 |

| 6 | 122.80 | 120.65 | 125.7 |

| 4 | 118.49 | ||

| 8 | 62.32 | 62.32 | 59.7 |

| 7 | 60.58 | 60.58 | 59.7 |

| 9 | 18.84 | 18.84 | 18.1 |

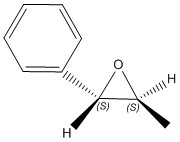

Optical rotation properties of the epoxides

Using the NMR output file for the epoxides, a new input file is created and the following command line was used:

# CAM-B3LYP/6-311++g(2df,p) polar(optrot) scrf(cpcm,solvent=chloroform) CPHF=RdFreq

and the following line was added at the end of each input file:

589nm 365nm

The output log file for the epoxides was then analysed and tabulated below.

| (3R,4S)-1,2-dihydronapthalene epoxide | (R,R)-trans-β-methyl styrene epoxide | |

|---|---|---|

|

| |

| Computed values | [alpha] (5890.0 A) = +35.86 o [alpha] (3650.0 A) = +209.45 o DOI:10042/26669 |

[alpha] (5890.0 A) = +46.77 o [alpha] (3650.0 A) = +137.67 o DOI:10042/26670 |

| Literature values | [alpha] (5890.0 A) = -39 o[6] | [alpha] (5890.0 A) = +47 o[8] |

The structure for the 1,2-dihydronapthalene epoxide was found to be an R,S configuration and therefore, from literature, the optical rotation was expected to be -39 o. This is not the case since the computed optical rotation for 589 nm was found to be +35.86 o. The calculated optical rotation value for the (R,R)-trans-β-methyl styrene was found to be +46.77 o and the value agrees with the literature of +47 o. There are no literature values to compare the optical rotation for the 365 nm.

Optical rotation is a method to find the enantiomer of a chiral compound. Each enantiomer should turn the plane of the polarised light in the opposite direction. Using this theory, the enantiomer of each of the epoxides are subjected to an optical rotation spectroscopy calculation. The results are shown below.

| (3S,4R)-1,2-dihydronapthalene epoxide | (S,S)-trans-β-methyl styrene epoxide | |

|---|---|---|

|

| |

| Computed values | [alpha] (5890.0 A) = -35.86 o [alpha] (3650.0 A) = -209.45 o DOI:10042/26667 |

[alpha] (5890.0 A) = -46.77 o [alpha] (3650.0 A) = -137.68 o DOI:10042/26668 |

| Literature values | [alpha] (5890.0 A) = +129 o[9] | [alpha] (5890.0 A) = -48.5 o[10] |

By changing the configuration to its enantiomer, the sign of the computed optical rotation changes. By comparing the values with the literature values, the computed optical rotation value for the 1,2-dihydronapthalene epoxide once again fails to agree with literature. The computed optical rotation value for the (S,S)-trans-β-methyl styrene epoxide agrees with literature for the 589 nm. There are no literature values found for the 365 nm.

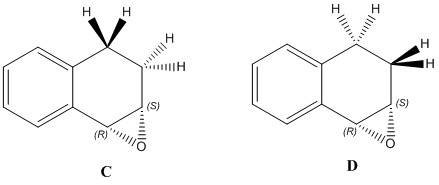

The optical rotation values for the trans methyl styrene were completely off and so, more investigation was carried out. This was done by changing the position of the hydrogen atoms in the cyclohexane ring as shown in the picture below. The new structure is higher in energy, and so is probably not the correct structure in reality. Upon calculation, the optical rotation sign changes and the magnitude differs by a large amount. Although the optical rotation values still do not agree with the literature values, it is closer for the (3S,4R)-1,2-dihydronapthalene epoxide. One thing that should be noted is that even though they are enantiomers, the literature values show that they do not turn the plane polarised light by the same magnitude.

| (3R,4S)-1,2-dihydronapthalene epoxide | (3S,4R)-1,2-dihydronapthalene epoxide | |

|---|---|---|

|

| |

| Computed values | A [alpha] (5890.0 A) = +35.86 deg [alpha] (3650.0 A) = +209.45 deg DOI:10042/26669 B [alpha] (5890.0 A) = -155.82 deg [alpha] (3650.0 A) = -522.15 deg DOI:10042/26729 |

C [alpha] (5890.0 A) = -46.77 deg [alpha] (3650.0 A) = -137.68 deg DOI:10042/26667 D [alpha] (5890.0 A) = +155.81 deg [alpha] (3650.0 A) = +522.13 deg DOI:10042/26728 |

| Literature values | [alpha] (5890.0 A) = -39 o[6] | [alpha] (5890.0 A) = +129 o[9] |

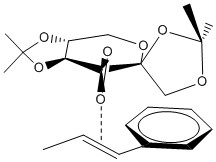

Calculated transition state for the reaction (β-methyl styrene)

Reactions occur when the reactants come together at the correct orientation and with the right energy. In this section, the orientations of the molecules at the transition state is analysed. For the reaction of the Shi catalyst with trans-β-methyl styrene, there are 8 possible ways at which the Shi catalyst and the alkene to approach together. The first factor is whether the catalyst comes from the top face or the bottom face of the alkene; this affects which oxygen of the dioxirane group is reacting with the alkene. The second factor is whether the phenyl group of the alkene is exo or endo with respect to the fructose. The third factor is whether the reacting alkene is R,R or S,S oriented. The third factor is fixed and so there will be 4 possible ways for each enantiomer, and the enantiomeric excess can be calculated from the data.

Reaction of Shi catalyst with trans-β-methyl styrene

| R,R series ΔG / a.u. | S,S Series ΔG / a.u. |

|---|---|

| -1343.022970 | -1343.017942 |

| -1343.019233 | -1343.015603 |

| -1343.029272 | -1343.023766 |

| -1343.032443 | -1343.024742 |

For each enantiomer, there are 4 possible paths the reaction might be occurring. For the enantiomeric excess calculation, the transition state with the lowest energy will be the one used to compare with the other enantiomer. This is because that the transition state with the lowest energy is the most stable state and is the most probable path of the reaction.

The transition state with the lowest energy for the RR series is the fourth possibility with -1343.032443 a.u.. For the SS series it would also be the fourth possibility with energy of -1343.024742. From these values, the enantiomeric excess can be calculated for the Shi catalyst. The calculations below shows that the R,R series is the more favored enantiomer and will be the one reacting more and will be the dominant product.

| Lowest free energy ΔG / a.u. | Difference in free energies, ΔΔG / a.u. | Difference in free energies, ΔΔG / J mol-1 | K, ratio of concentrations, exp-(D/RT) | enantiomeric excess, [(K-1)/(K+1)] * 100% / % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R,R series -1343.032443 |

-0.007701 | -20218.97704 | 3499.409008 | 99.94 |

| S,S series -1343.024742 |

Reaction of Jacobsen catalyst with trans-β-methyl styrene

| S,S series ΔG / a.u. | R,R Series ΔG / a.u. |

|---|---|

| -3383.262481 | -3383.253816 |

| -3383.257847 | -3383.254344 |

| Lowest free energy ΔG / a.u. | Difference in free energies, ΔΔG / a.u. | Difference in free energies, ΔΔG / J mol-1 | K, ratio of concentrations, exp-(D/RT) | enantiomeric excess, [(K-1)/(K+1)] * 100% / % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R,R series -3383.254344 |

-0.008137 | -21363.69513 | 5554.456819 | 99.96 |

| S,S series -3383.262481 |

The same type of calculations were carried out for the Jacobsen catalyst reacting with the alkene and the transition state shows that the S,S alkene is lower in energy compared to the R,R alkene and therefore will be the dominant product. This means that by using a different catalyst, the end product will be different and this information can be used to synthesise the desired product.

Reaction of Jacobsen catalyst with cis-β-methyl styrene

| S,R series ΔG / a.u. | R,S Series ΔG / a.u. |

|---|---|

| -3383.259559 | -3383.251060 |

| -3383.253442 | -3383.250270 |

| Lowest free energy ΔG / a.u. | Difference in free energies, ΔΔG / a.u. | Difference in free energies, ΔΔG / J mol-1 | K, ratio of concentrations, exp-(D/RT) | enantiomeric excess, [(K-1)/(K+1)] * 100% / % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S,R series -3383.259559 |

-0.008499 | -22314.1262 | 8151.428738 | 99.98 |

| R,S series -3383.251060 |

The same procedure is carried out with the Jacobsen catalyst reacting with the cis-β-methyl styrene and the calculation shows that the S,R alkene is the more favored transition state and will react to give the dominant product.

Non-covalent interactions (NCI) in the active-site of the reaction transition state

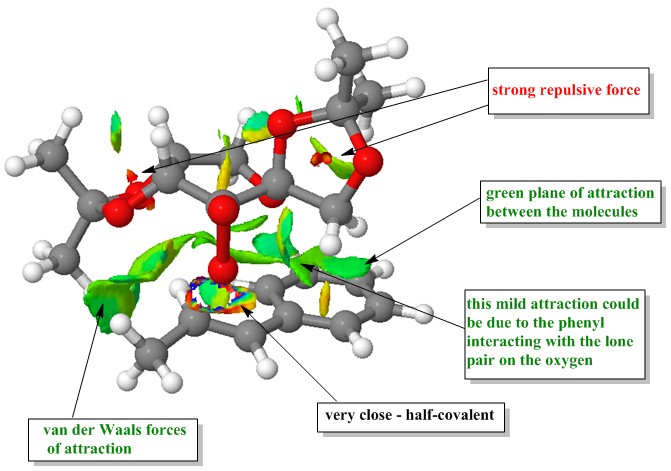

Non-covalent interactions (NCI) are interactions between atoms as a results of electromagnetic interactions. They are not covalent bonds in which electrons are shared between the atoms and so the interactions are slightly weaker than covalent bonds. They can be found to occur between molecules or within the molecule itself. These interactions include hydrogen bonding, short range repulsion, dipolar interactions, electrostatic interactions and van der Waals forces. They are weak individually, but combining all the forces can be significant. One of the transition states of the Shi epoxidation of R,R-trans-β-methylstyrene was computed in 3-D space to investigate the non-covalent interactions in this transition state. This is the first possibility of the R,R transition state where the phenyl group of the alkene is exo relative to the fructose.

| NCI in the transition state of Shi epoxidation of trans-β-methyl styrene | |

|---|---|

Key: red - strongly repulsive, yellow - mildly repulsive, green - mildly attractive, blue - strongly attractive |

|

| The first thing to note in this NIC transition state picture is that the oxygen appears to be very close to the C=C double bond, this is where the new bond is formed and therefore is not counted as a non-covalent bond. The next thing to notice is that there is a green plane between the molecules as the catalyst approaches the alkene showing that there are mild attractive forces between the molecules in this area. This is due to a number of reasons.

Firstly, at the left side of the picture, there is a methyl group from the catalyst lying close next to the methyl tail of the methyl styrene. This results in van der Waals forces to occur between them which make the two methyl groups to attract each other. The second reason is that on the right side of the picture, it can be seen that phenyl group of the alkene having a mild attraction with the catalyst. This could be due to the π-bond of the phenyl ring stacking with the lone pair of the oxygen in the middle ring of fructose resulting in the mild attraction between the two. Overall, these mild attractions pull the catalyst closer to the alkene resulting in easier transfer of the oxygen into the double bond and thus decreasing the energy of the transition state, even though there is a strong repulsive force that can be seen occurring between the oxygen atoms within the fructose rings due to them being too close to each other. | |

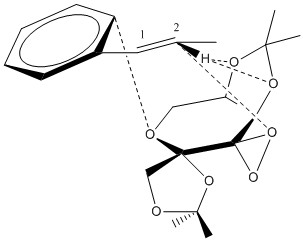

Electronic topology (QTAIM) in the active-site of the reaction transition state

Quantum Theory of Atoms In Molecules (QTAIM) is a method to calculate the position of the electron density in a covalent bond and also the weaker non-covalent interactions. This analytical method goes hand-in-hand with the NCI analysis and therefore the same transition state as used in the NCI study was used for the QTAIM analysis.

| QTAIM of the transition state of Shi epoxidation of trans-β-methyl styrene | |

|---|---|

|

|

| In QTAIM, there are two distinct types of bonds: one is the covalent bond, shown by the solid lines and another is the weaker NCI, shown by the dashed lines. In the covalent bonds, it should be shown that for homonuclear covalent bonds, the BCP (electron density) lies in the middle of the bond while for heteronuclear covalent bonds, the BCP lies closer to one of the nuclei.

The interesting part for the QTAIM analysis in this transition state is on the NCI. From the QTAIM, it can be shown that one of the oxygen atoms from the dioxirane group coordinating with the C2 while the oxygen atoms from the back ring coordinates with the hydrogen atom attached to the C2 which might help with the oxygen transfer across the double bond. This also suggests that if the reaction were to occur using this transition state, the oxygen would selectively attack the C2 first and that the epoxide formation is not a concerted reaction. It also interesting to note that since the other oxygen atom in the dioxirane group is pointing down, it is too far to coordinate with the alkene and therefore not having an NCI with the carbon or the hydrogen. The second thing to note with the NCI is that there is an NCI formed between the oxygen in the fructose ring with the phenyl ring of the alkene. This proves that there are interactions between π-orbitals of the phenyl ring and the lone pair of the oxygen atom as has been suggested in the previous section. | |

References

- ↑ S. J. Cristol, W. K. Seifert, and S. B. Soloway, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1960, 82, 2351–2356.

- ↑ S. Elmore and L. Paquette, Tetrahedron letters, 1991, 6, 319–322.

- ↑ J. Bredt, "Über sterische Hinderung in Brückenringen (Bredtsche Regel) und über die meso-trans-Stellung in kondensierten Ringsystemen des Hexamethylens", Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie, 1924, 437, 1-13

- ↑ W. Maier and P. Schleyer, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 1981, 1891–1900.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 L. Paquette and N. Pegg, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1990.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 H. Lin, J. Qiao, Y. Liu, and Z.-L. Wu, Journal of Molecular Catalysis B: Enzymatic, 2010, 67, 236–241.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 P. C. B. Page, P. Parker, B. R. Buckley, G. a. Rassias, and D. Bethell, Tetrahedron, 2009, 65, 2910–2915.

- ↑ G. Fronza, C. Fuganti, P. Grasselli, and A. Mele, J. Org. Chem., 1991, 56, 6019–6023.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 S. Pedragosa-Moreau, A. Archelas, and R. Furstoss, Tetrahedron, 1996, 52, 4593–4606.

- ↑ P. Besse, M. Renard, and H. Veschambre, Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, 1994, 5, 1249–1268.