Rep:Mod:ms7109 module3

Module 3: Modelling Transition states

The Cope Rearrangement

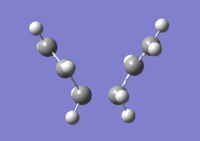

The Cope rearrangement is a type of pericylclic reaction whereby one σ bond is formed and another is broken in a concerted manner. 1,5-hexadiene can undergo this rearrangement proceeding via a "chair" or a "boat" transition state, since the new bond formed lies between positions three it is termed as [3,3] sigmatropic.

The objective of this computational experiment is to calculate and identify the lowest energy reactants, products and the two possible transition states by means of optimising their structures and using the results to determine the preferred reaction mechanism.

Optimizing the reactants and products

1,5-hexadiene has two limiting conformations, antiperiplanar and gauche, each of which have even more possible conformations differing by the orientation of the two double bonds relative to the central carbon atoms. All these structures can be located by drawing them on gaussview and optimizing them at a HF/3-21G level, as a result six of them have been found to have the "gauche" linkage whereas only four have the "anti" linkage.

Experimental data report that alkanes in the anti-periplanar (app) conformation are more stable than in the gauche. Interactions between orbitals anti-periplanar to each other such as σC-H/σ*C-H together with bond-bond Pauli repulsions favour the former whilst a higher number of Van der Waals H..H contacts help to stabilise the latter. Since the central four atoms are sp3 hybridized these effects can be applied to 1,5-hexadiene.

Below are the conformers named as in Appendix 1

| Structure |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Point group | C2 | C2 | C1 | C2 | C1 | C1 |

| Energy (Hartrees) | -231.68772 | -231.69167 | -231.69267 | -231.69153 | -231.68962 | -231.68916 |

| Structure |  |

|

|

|

| Point group | C2 | Ci | C2h | C1 |

| Energy (Hartrees) | -231.69260 | -231.69254 | -231.68907 | -231.69097 |

The lowest energy conformation is gauche3 with an energy of -231.6927 a.u. This disagrees with both the experimental result and the anti-periplanar stabilsing effects discussed above. Nonetheless, 1,5-hexadiene has two double bonds whose orbital interactions must be considered too. A possible overlap of π-orbitals in the gauche form may override the anti-periplanar stabilsing effects by lowering the conformational energy below that of the anti. This π-orbital overlap cannot occur in the anti conformers as the double bonds are positioned too far from each other. However, anti1 and anti2 are only just higher in energy then gauche3 by about 0.04 and 0.08 kcal mol-1 respectively, thus errors in the calculation become significant and deciding which of the three is most stable cannot be done.

The anti2 conformer is reoptimized with B3LYP method and 6-31G(d) basis set, this has much higher accuracy and is expected to give a lower energy minimum. Since two different methods are used for the optimization, the final energies of the structures cannot be compared directly, thus the geometry parameters provide an alternative for determining which method runs the best optimization.DOI:10042/to-11588

| Parameter | HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G(d) | Literature[1] |

| Energy (Hartrees) | -231.6926 | -234.6117 | n/a |

| C3-C4 (Å) | 1.553 | 1.548 | 1.536 |

| C2-C3 (Å) | 1.509 | 1.504 | 1.508 |

| C1=C2 double bond (Å) | 1.316 | 1.334 | 1.341 |

| C-H (Mean)(Å) | 1.078 | 1.092 | 1.108 |

| C2-C3-C4 (°) | 111.3 | 112.7 | 111.0 |

| C1=C2-C3 (°) | 124.8 | 125.3 | 122.5 |

| C2=C1-H (°) | 121.9 | 121.7 | 120.4 |

| C3-C2-H (°) | 115.5 | 115.7 | 118.4 |

| H-C3-H (°) | 107.7 | 106.7 | 107.1 |

The resulting energies are different, but as discussed above they cannot be compared. Bond lengths and angles measured using both methods are very similiar to the reported values, however, DFT calculated lengths and angles resemble them more since the higher accuracy does generate the most stable structure.

In order to compare energies, a B3LYP/6-31G(d) frequency calculation needs to be performed on the anti2 structure to obtain additional information and corrections to the overall energy. In addition, the resulting frequencies can confirm whether or not a minimum was reached during the optimisation.DOI:10042/to-11566

| Energy (hartree) | |

| Sum of electronic and zero point energies (E = Eelec + ZPE) | 234.4692 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal energies (E = E + Evib + Erot + Etrans) | 234.4619 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal enthalpies (H = E + RT) | 234.4609 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal free energies (G = H - TS) | 234.5008 |

These four terms can tell us a lot more about the structure than just the final energy. The first is the potential and zero-point vibrational energy at 0K, the second is the added sum of translational, rotational and vibrational energies at 298.15K and 1atm, the third is the enthalpy calculated from the total energy but taking into account RT and finally the fourth is the free energy considering entropic contributions.

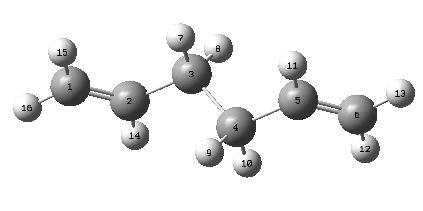

Frequency calculation identifies 42 vibrational modes, all of which are real and positive, thus a minimum is indeed reached. Its spectrum is shown on the left, C-H stretches give rise to four strong peaks between 3000 to 3300 cm-1, the double bonds come up at 1734 cm-1 and numerous peaks from C-H bending are also present at 1036, 940 and 670 cm-1.

Optimizing the "Chair" and "Boat" Transition Structures

During the Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene the product is reached via two possible transitions states. There are numerous ways to minimize energies of transition states, some more reliable and time consuming others the opposite way around, nonetheless they all differ from normal optimizations as a defined reaction coordinate has to be set beforehand.

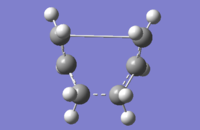

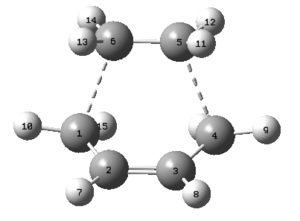

Chair Structure

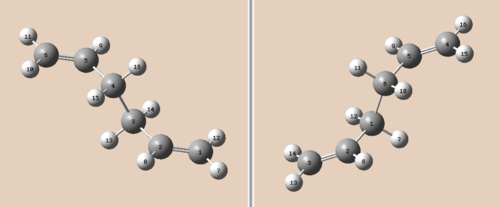

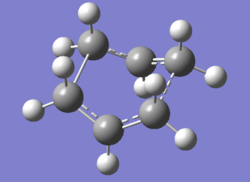

The first method requires computing a force constant at the beginning of the calculation and uses the Gaussian optimization for a transition state: TS(Berny). This only works when the guessed structure of the transition state nearly matches the exact structure. Since the chair geometry is well known, two allyl fragments (CH2CHCH2) were made to resemble it by optimizing and positioning them one over the other so that the distance between two terminal carbons was 2.2Å as shown below. Once this was done, the optimization+frequency was run by calculating the force constant once at the HF/3-21G level with an additional warning to prevent calculations from failing if more than one imaginary frequency appears during the optimization. The optimised structure has an energy of -231.6193 a.u., the distance between carbon atoms on two separate fragments reduces from 2.20 to 2.02Å and an imaginary vibrational mode at -818 cm-1 is identified. This mode corresponds to what happens during the rearrangement process, a σ bond on one side of the molecule breaks whilst a σ bond on the other forms at the same time.DOI:10042/to-11585

The second method involves freezing the reaction coordinate and once the structure is relaxed a similar optimisation to method one can be performed. On gaussview the bond between two pairs of terminal carbons was initially frozen using the redundant coordinate editor and the structure optimised to a minimum. Consequently, these bonds were changed to "derivative" and a transition state optimisation (TSBerny) run without computing any force constants. The imaginary vibrational mode at -818 appears again, it has a final energy of -231.6193 and the distance between the two terminal carbon atoms reduces from 2.20Å after minimisation to 2.02Å after TS(Berny).DOI:10042/to-11576 DOI:10042/to-11581

|

|

|

The two methods give the same final optimized structure with equal bond lengths, energies and frequencies. Therefore both are useful in determining the most stable transition state, however, when force constant calculation is more complicated, differentiating along the reaction coordinate as in method two can be easier as the whole Hessian doesn't have to be computed.

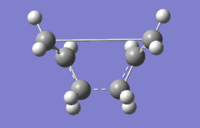

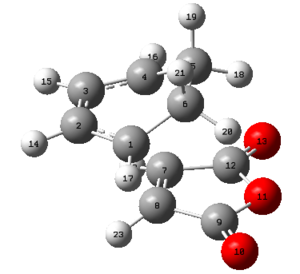

Boat Structure

This optimization is different from that for the chair structure since the transition state is not drawn in manually, instead it is solved computationally from the reactant and product. For the QST2 method to work the atoms in the product have to be numbered according to the reactant's atoms after rearrangement, therefore two anti2 conformers are placed next to each other and altered correspondingly. A TS(QST2)Opt+Freq calculation is then carried out at HF/3-21G.DOI:10042/to-11590

|

|

|

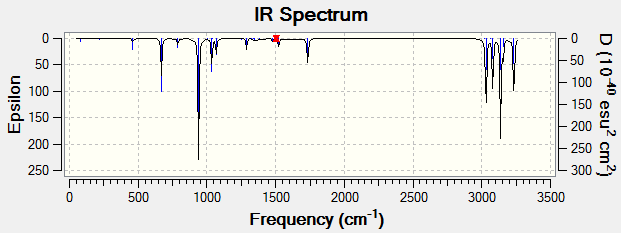

Unexpectedly the optimisation failed, a more chair-like structure was identified as the transition state due to lack of rotation around the central bond. Starting from the most stable reactant and product will not lead to a boat transition state thus it is necessary to modify these structures; the central C2-C3-C4-C5 dihedral angle is set at 0° and the internal C2-C3-C4/ C3-C4-C5 angles are reduced to 100°. An identical optimisation is run on these modified structures.DOI:10042/to-11591

|

|

|

After this modification a successful "boat" transition state structure was obtained. It's frequency calculation also yielded one imaginary vibrational mode at -840 cm-1 thus the calculation converged, this mode arises from the rearrangement reaction as for the "chair". QST2 method is therefore very useful and efficient in identifying the transition structure but it may fail if the starting reactant and product structures are not ideal.

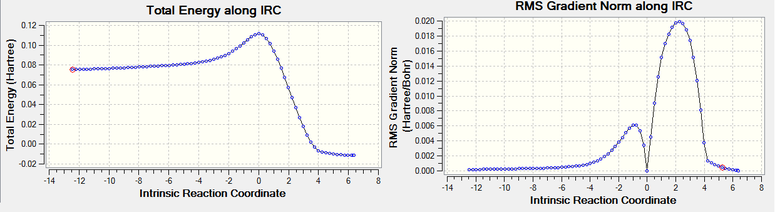

IRC methods

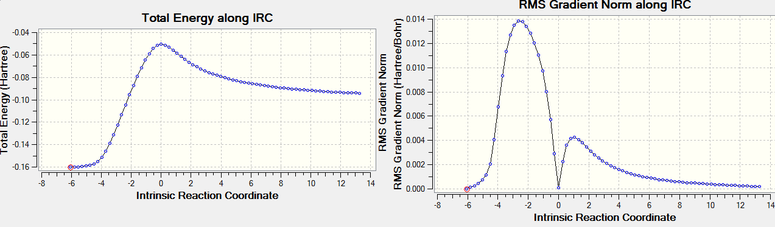

To determine which product conformer of 1,5-hexadiene will form after the transition state one can use an Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate method. It basically tracks the structures between the transition state and the product by descending the potential energy surface curve down to the local minimum and analyzing a number of geometry steps.

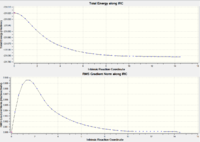

For the Chair structure the first IRC will be run in the forward direction since the reaction coordinate is symmetrical, the force constant will be calculated once and the number of points increased to 50. DOI:10042/to-11585

|

|

The IRC calculation identified 26 intermediate geometries out of the requested 50, their energies and RMS gradients are displayed above together with the animation of how the reaction proceeds. The energy graph shows how the energy decreases to a final structure at -231.6891 a.u. however this is not yet the minimum since the gradient curve does not reach zero. In order to achieve the lowest possible energy geometry three things can be done: i) take the last point from IRC and run a minimization, this is the fastest way but unless this point is very close to the actual minimum it might lead to a less stable structure. ii) redo the IRC specifying a higher number of points, however if too many points are needed the IRC might take another path. Finally iii) to compute the force constants at every step which is the most reliable. Needless to say, method ii) is of no use because asking the calculation to compute more points will still only produce 26. DOI:10042/to-11571 DOI:10042/to-11572

The two improvements i) and iii) successfully obtain more stable structures, both of which are 6.8 kJ mol-1 lower in energy than the initial IRC. Method ii) reaches a gradient closer to zero yet the two final structures are very similar as shown by the formed/broken bond lengths and their corresponding images. Gauche2 is the conformer which connects this chair transition state, this is confirmed by its identical energy to the structures obtained from IRC of -231.6917 a.u..

An equivalent approach can be done on the Boat transition state. Firstly the simple IRC method (calaculating the force constant once)is run, then the minimisation of the last point structure and lastly the IRC with the force constant computed at every step. DOI:10042/to-11570 DOI:10042/to-11569 DOI:10042/to-11568

|

|

The same pattern as the chair transition state occurs, the initial IRC finds 26 intermediates, optimisation of the 26th and second IRC locate a more stable structure (15.2 kJ mol-1 lower) due to convergence at the minimum. This resulting structure has an energy of -231.683 a.u. but it doesn't correspond to any of the conformers.

Activation Energies

To work out the activation energy, the energy of the transition states and reactant has to be known. Therefore an optimization + frequency analysis of both transition states and the anti2 reactant is run at the HF/3-21G and B3LYP/6-31G* levels of theory. Thermodynamic data from the result of the calculations is tabulated below together with the activation energies (Difference in energy between transition state and anti2 reactant) of the "chair" and "boat" at 0K and 298.15K. DOI:10042/to-11562 DOI:10042/to-11564 DOI:10042/to-11566 DOI:10042/to-11589

| Structure | HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G(d) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic energy | Sum of electronic and zero-point energies | Sum of electronic and thermal energies | Electronic energy | Sum of electronic and zero-point energies | Sum of electronic and thermal energies | |

| at 0 K | at 298.15 K | at 0 K | at 298.15 K | |||

| Chair TS | -231.61932 | -231.46670 | -231.46134 | -234.55698 | -234.41492 | -234.40900 |

| Boat TS | -231.60280 | -231.45092 | -231.44529 | -234.54309 | -234.40234 | -234.39601 |

| Reactant (anti2) | -231.69253 | -231.53954 | -231.53257 | -234.61170 | -234.46921 | -234.46196 |

| HF/3-21G | HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G(d) | B3LYP/6-31G(d) | Expt. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| at 0 K | at 298.15 K | at 0 K | at 298.15 K | at 0 K | |

| ΔE (Chair) | 45.68 | 44.68 | 34.07 | 33.20 | 33.5 ± 0.5 |

| ΔE (Boat) | 55.60 | 54.71 | 41.98 | 41.35 | 44.7 ± 2.0 |

In the first table we can see that the DFT values are all lower by about 3 a.u., however the geometries from the two methods are very similar. Activation energies for the chair structure at 0K, 298.15K and in either method are all lower than the boat, this suggests that the Cope rearrangement reaction proceeds via a chair transition state. By comparing the Activation energies at 0K with literature[2] shows that the calculated values match the ones reported, furthermore it demonstrates how the B3LYP/6-31G* method produces more accurate results.

The Diels Alder Cycloaddition

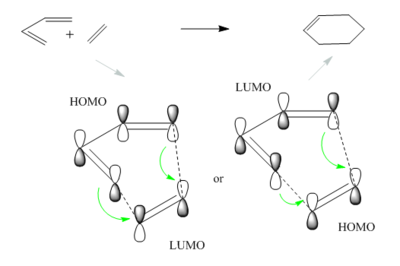

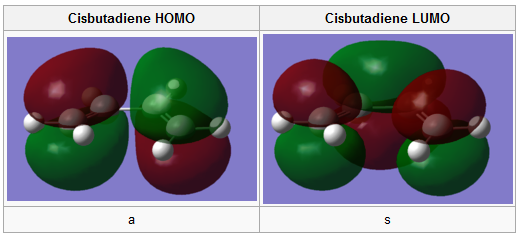

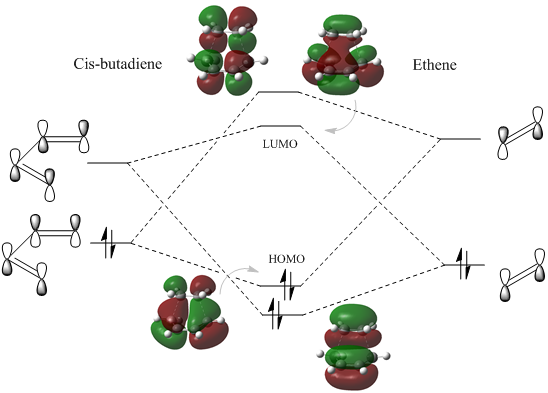

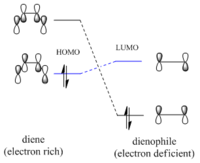

A Diels Alder Cycloaddition is a type of pericyclic reaction where π orbitals of a dieneophile and diene interact to form new σ bonds. This is a concerted process which usually involves the HOMO or LUMO from one fragment overlapping with the LUMO or HOMO of the other fragment correspondingly, leading to a bonding and an antibonding molecular orbital. What determines whether a specific HOMO-LUMO interaction is allowed is their related symmetries, hence the reaction is forbidden when the frontier molecular orbitals (FMO) are asymmetric to one another. Analyzing the transition state and computing its electron density can produce a molecular orbital diagram useful in determining which FMO's are responsible for the cycloaddition. The typical dienophile and diene for Diels Alder are ethylene and cis-butadiene which react to give cyclohexene.

Cis-butadiene belongs to the C2v point group whilst ethylene to D2h. Both have numerous symmetry elements but the particular σv plane which cuts across the ethylene double bond and the butadiene single bond will be used to analyse the orbital symmetries since it is also present in the transition state and the product.

The linear combination of atomic orbitals can be predicted qualitatively; double bonds have a π(bonding) and π*(antibonding) orbital, for ethylene these are the HOMO and LUMO whereas in the case of butadiene the π orbitals of the two alkenes combine to generate the HOMO and LUMO as depicted in figure 4.

Optimizing the reactants

To generate molecular orbitals, an optmisation using the semi empirical AM1 method was run on both cis-butadiene and ethylene. This particular calculation solves the Schrodinger's equation for electron density and allows the MO's to be visualized graphically. In addition they are all assigned a symmetry about the σv plane, s for symmetric and a for antisymmetric. DOI:10042/to-11557 DOI:10042/to-11558

|

|

A comparison between these computed MO's and the LCAO's in Figure 4 show a very decent resemblance, the only correction to the LCAO's π bonding orbitals is the fact that they should be represented as single electron clouds on top and at the bottom of the double bond rather than two equally oriented p orbitals. Nonetheless, the symmetry along the σv plane is determined for each orbital . For the reaction to proceed the HOMO of butadiene should overlap with the LUMO of ethene and the LUMO of butadiene with the HOMO of ethene. To prove this expectation the transition state has be examined.

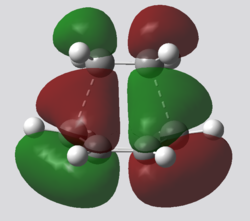

Analysing the transition state

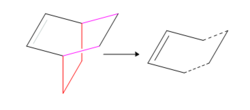

The transition state is known to have an envelope type structure which can be drawn on gaussview starting from a bicyclo system. A -CH2-CH2- fragment is initially removed, then a single C-C bond converted to a double bond and finally the bonds to the remaining -CH2-CH2- fragment turned into dashed lines 2.2Å in length. This is the guessed transition state structure (figure 5) which is optimised by freezing the forming σ bonds, minimising the geometry of the fragments and then running a TS(Berny) Optimization at the AM1 level. DOI:10042/to-11556 DOI:10042/to-11555

To determine whether the transition state is obtained, the energy, geometry and its vibrational modes are studied and tabulated below.

The RMS gradient tends to zero therefore the optimisation has reached a minimum with an energy of 0.112 a.u. As can be seen C-C bond lengths are all short off the ideal carbon-carbon single bond length of 1.54Å and the double bond is longer than the ideal C=C length of 1.34Å. This implies that these particular bonds are changing, possibly from σ to π bonds or vice versa, and therefore the corresponding structure rests between the reactants and the product. Two σ bonds are supposed to form between the two fragments, their length is 2.12Å which compared to a C-C bond (1.54Å) is too high, however it lies within two carbon Van der Waals radii (3.40Å) suggesting that electron density overlap between the terminal carbons is indeed occurring. Finally both H-C-H angles are half way between an sp3 (120°) and sp2 (109°) hybridized carbon confirming again the transition of bonds from σ to π or vice versa.

One imaginary vibration results from the frequency calculation at -956 cm-1 corresponding to the concerted σ bond formation between cisbutadiene and ethene, or in other words the overlap of their frontier molecular orbitals. The lowest vibration at 147 cm-1 is the asynchronous twisting motion of the fragments about the weakest partly formed C-C bond. Molecular orbitals of the transition state can be used to determine all HOMO-LUMO interactions present.

| TS HOMO | TS LUMO |

|---|---|

|

|

| a | b |

The computed MO diagram for the transition state has two particular bonding and antibonding orbitals, these arise from the combination of orbitals with similar symmetry in the two reactants. Therefore the HOMO of cis-butadiene overlaps with the LUMO of ethene since both are antisymmetric along the σv plane, whereas the LUMO of cis-butadiene with the HOMO of ethene as they are symmetric. Both overlaps produce a bonding and antibonding MO which retain their symmetry.

To show the reaction process, an Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate calculation can be run on the transition state asking it to compute the force constant at every step, run it in both directions and to find 50 points. As a result, 78 intermediate geometries were identified, starting from the two independent reactants, passing over the transition state (RMS curve goes to down to zero) and dropping down to the low energy product. DOI:10042/to-11549

|

|

Studying the regioselectivity of the Diels Alder Reaction

Another type of [4πs+2πs] Diels Alder reaction is the cycloaddition of cyclohexa-1,3-diene with maleic anhydride to form a bridged addition of the two. This time the dienophile has an ethanoic anhydride substituent closing the double bond to form a ring whilst the diene is also a cyclic molecule forcing us to consider possible steric implications between the two. One interesting outcome of this reaction is the regioselectivity of the products. It is reported that the Endo product is favoured over the Exo in a kinetically controlled reaction; even though Exo is thermodynamically more stable, a secondary orbital interaction is present in the Endo which stabilises its transition state. Both TS structures will be computed in order to investigate the effects described above.

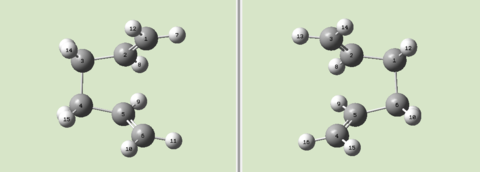

Initially a cyclohex-1,3-ene fragment is drawn on gaussview and put over a maleic anhydride fragment, by rotating the cyclohex-1,3-ene ring either the exo or the endo can be obtained. To optimise these transition structures the freeze coordinate method is once again used by freezing the new σ bonds, minimizing and then optimising to a TS(Berny) at AM1 level. DOI:10042/to-11553 DOI:10042/to-11552

The endo transition state is 2.89 kJ mol-1 lower in energy than the exo confirming that it is in fact the kinetically favoured isomer. This preference is partly due to steric repulsions between the anhydride carbons and the sp3 hybridised carbons in the cyclohexdiene ring for the exo isomer. The Van der Waals radius for C-C is 3.40Å whereas for C-H it is 2.89Å, comparing these with the through space C---C and C---H distances it shows that for the Exo they are both shorter. In the endo, the carbons in the cyclohexdiene are sp2 so the C---H distance is longer resulting in lower steric clash but the C---C are shorter because of electronic effects discussed below.

Since the -(C=O)-O-(C=O)- functional group is electron withdrawing the dienophile will be electron deficient and its orbitals will lie lower in energy than the diene's. Therefore the predominant interaction will be between the LUMO of the diene and the HOMO of the dieneophile because their energy difference is smaller and the bonding molecular orbital will be more stabilised as shown in figure 7[3]. The molecular orbitals of both exo and endo transition states are obtained after running the AM1 optimisation and the significant ones are shown below.

| Molecular orbital | Exo Isomer | Endo Isomer |

| HOMO |  |

|

| HOMO-1 |  |

|

The HOMO for both structures arises from the LUMO-HOMO combination of the reactant's orbitals led by normal electron demand as in figure 7 and will not show any overlap between the newly formed double bond and the anhydride oxygen lone pairs. On the other hand the HOMO-1 is the combination of the diene HOMO and the dienophile LUMO (inverse electron demand) and it shows how the π bonding orbital of the double bond is in phase with all the oxygen lone pairs giving rise to a secondary orbital overlap. However, this is only present in the Endo form and is another factor contributing to the stabilisation of the endo transition state.

A final IRC is calculated for both transition states, again asking to compute the force constant at every step in the backwards and forward direction. 74 intermediates were found for the exo and 76 for the endo, however the endo curve seems to start from the product. If this graph is turned around the two isomers can be compared; both curves behave similarly as expected, only that the exo reaches a higher energy transition state but its product has a lower energy than the endo. This confirms that under kinetic control the endo isomer will prevail but the reverse occurs when the reaction is heated as the exo is the thermodynamic product. DOI:10042/to-11551 DOI:10042/to-11550

| Exo | |

|

|

| Endo | |

|

|

Conclusion

Transition states in many reactions are the key to understanding what occurs in them. For example for the two reactions discussed, the Cope rearrangement and the Diels Alder the corresponding transiton state explains why a certain product is formed over others. However, transition states are hard to isolate experimentally and computational chemistry is a very good alternative. It allows them to be optimised in a number of methods and to compare them with all possible structures. Frequency calculations enable us to obtain electronic information of the molecule such as infrared vibrations or molecular orbitals based on complicated equations. Finally these are then used to substantiate experimental data or to even discover new effects present in the transition state. The Cope rearrangement is found to proceed via a chair transition state rather than a less stable boat structure, Diels Alder between cis-butadiene and ethene is driven by frontier molecular orbital overlap whilst the cycloaddition of maleic anhydride with cyclohex-1,3-diene is regioselectively controlled by secondary orbital interactions and steric clashes between the two rings.

References

- ↑ G. Schultz, I. Hrgittai, J. Mol. Struct., 1995, 346,63-69

- ↑ Wiest, O.; Black, K.A.; Houk, K.N., J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1994, 116, 10336-10337DOI:10.1021/ja00101a078

- ↑ A.C. Spivey, Heteroaromatic Chemistry course, Imeprial College London 2011