Rep:Mod:mod3 jb

Module 3 - Yr 3 Computational Lab: Jessica Bevan

Introduction

The aim of this module is to show how computational chemistry can be used to model transition states which lead to a greater understanding of reaction mechanisms. In order to do this, specific techniques have to be used in order to take account of the breaking and making of bonds.

The Cope Rearrangement Tutorial

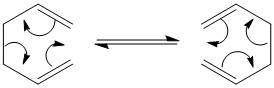

The Cope Rearrangement is a pericyclic reaction of 1,5 diene in which a [3,3] sigmatropic rearrangment occurs as outlined in the below diagram [1]:

The rearrangement can go through one of two transition states; chair or boat.

The exact nature of the transition state changes according to the substituents and can range from resembling two independant allyl radicals and a cyclo hexane 1, 4 di radical. This is illustrated in the below diagram [2]:

In the majority of reactions, the transition state is late and the bonds between C1 and C6 are developed.

Optimising the Reactants and Products

Hexadiene can exhibit two conformers, which each in turn can exhibit isomerisation through rotation of the CHCH2 groups. The dihedral angle between the two CHCH2s for Gauche conformers is 60o, whereas Anti has a dihedral angle of 180o. All analysed possibilities are outlined below. There are a couple of others yet to be analysed.

The following data was obtained by optimising the conformers using HF/3-21G level of theory.

| Gauche 4 | Gauche 2 | Gauche 3 | Gauche 1 | Gauche 5 | |

| File Type | .fch | .fch | .fch | .fch | .fch |

| Calculation Type | FOPT | FOPT | FOPT | FOPT | FOPT |

| Calculation Method | RHF | RHF | RHF | RHF | RHF |

| Basis Set | 3-21G | 3-21G | 3-21G | 3-21G | 3-21G |

| Charge | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Spin | Singlet | Singlet | Singlet | Singlet | Singlet |

| Total Energy (a.u.) | -231.6915304 | -231.6916670 | -231.6926612 | -231.6877159 | -231.6896158 |

| RMS Gradient Norm (a.u.) | 0.00001006 | 0.00000172 | 0.00000848 | 0.00006151 | 0.00000458 |

| Dipole Moment (Debye) | 0.1281 | 0.3806 | 0.3406 | 0.4562 | 0.4438 |

| Point Group | C2 | C2 | C1 | C2 | C1 |

| DOI:10042/to-12224 | DOI:10042/to-12455 | DOI:10042/to-12456 | DOI:10042/to-12457 | DOI:10042/to-12462 |

The table above displays all analysed gauche conformers, whereas the below table shows the anti.

| Anti 3 | Anti 1 | Anti 2 | |

| File Type | .fch | .fch | .fch |

| Calculation Type | FOPT | FOPT | FOPT |

| Calculation Method | RHF | RHF | RHF |

| Basis Set | 3-21G | 3-21G | 3-21G |

| Charge | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Spin | Singlet | Singlet | Singlet |

| Total Energy (a.u.) | -231.6890707 | -231.6926024 | -231.69253528 |

| RMS Gradient Norm (a.u.) | 0.00000819 | 0.00001824 | 0.00001042 |

| Dipole Moment (Debye) | 0.0001 | 0.2021 | 0.0003 |

| Point Group | C2h | C2 | Ci |

| DOI:10042/to-12226 | DOI:10042/to-12228 | DOI:10042/to-12227 |

Order of stability:

Anti 3 < Gauche 1 < Gauche 5 < Gauche 4 < Gauche 2 < Anti 2 < Anti 1 < Gauche 3

In order to understand the reasons behind the differing stabilities one has to consider three general effects[3].

1) Favourable interactions between sigma orbitals and sigma* orbitals.

2) Bond-bond Pauli repulsion

3) H---H interactions

In general, effect 2 disfavours and effect 3 favours gauche. Most of the time, effect 1 becomes the deciding factor in determining stability. The fact that gauche suffers from steric strain would suggest it is less stable than anti, and it surprising that Gauche 3 is the most stable. NBO analysis would shed light on this.

Anti 2 Opt

Anti 2 was optimised using two different methods. Firstly using the HF/3-21G then B3LYP/6-31G*, and the results are displayed in the table below.

All discussed angles and lengths are picture in the jmol provided.

| File Name | anti2_opt | anti2_opt631g |

| File Type | .log | .fch |

| Calculation Type | FOPT | FOPT |

| Calculation Method | RHF | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 3-21G | 6-31G(D) |

| Charge | 0 | 0 |

| Spin | Singlet | Singlet |

| E RHF (a.u.) | -231.69253528 | -234.61171035 |

| RMS Gradient Norm (a.u.) | 0.00001042 | 0.00001327 |

| Imaginary Freq | ||

| Dipole Moment (Debye) | 0.0003 | 0.0000 |

| Point Group | Ci | Ci |

| Dihedral Length (nm) | 0.354 | 0.361 |

| Angle between CH2-CH-CH2 (o) | 124.8 | 125.2 |

| Central Dihedral Angle | 180.00 | -179.99 |

| DOI:10042/to-12227 | DOI:10042/to-12573 | |

Comparing the dihedral lengths on each it can be seen that the method using 6-31G gives a longer molecule. This is because the angle between CH2-CH-CH2 is bigger. The overall change is very small.

Anti 2 Frequency Analysis

| Method | 3-21G | 6-31G | Literature [4] |

| Symmetric C=C Frequency (cm -1) | 1855.58 | 1731.07 | 1643 |

| Symmetric C=C Intensity | 0.0008 | 0.0000 | |

| Asymmetric C=C Frequency (cm -1) | 1858.09 | 1734.31 | - |

| Asymmetric C=C Intensity | 16.8650 | 19.4920 | |

| DOI:10042/to-12562 | DOI:10042/to-12230 |

As you can see, both methods differ from each other and literature for their frequencies. The closest to literature is the 6-31G method.

The following energies will be used to look at activation energy:

Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies = -234.469204

Sum of electronic and thermal Energies = -234.461857

Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies = -234.460913

Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies = -234.500777

Optimising the "Chair" Transition Structures

The Chair transition structure was optimised by first optimising an allyl CH2CHCH2 fragment using HF/3-21G theory then combining two of these fragments together, with the terminal carbons at a distance of 2.2A apart.

It was then minimised by two different methods.

Firstly, using HF/3-21G and optimising to a TS (Berny). The force constant was caluclated once and Opt=NoEigen entered into key words to stop the program crashing if more than one imaginary frequency is found. The results are below:

| File Name | OPT_FREQ |

| File Type | .fch |

| Calculation Type | FREQ |

| Calculation Method | RHF |

| Basis Set | 3-21G |

| Charge | 0 |

| Spin | Singlet |

| Total Energy (a.u.) | -231.61932239 |

| RMS Gradient Norm (a.u.) | 0.00002067 |

| Dipole Moment (Debye) | 0.0003 |

| DOI:10042/to-12236 |

The imaginary peak, shown below, was at -817.95, which indicates the correct minimum was reached.

The chair was then minimised in an alternate way, using the freeze bond method. The co ordinates of the bond breaking/making carbons were frozen, the geometry optimised, then unfrozen, set as derivatives and reoptimised.

| File Name | Bonds - Frozen | Bonds - Derivative |

| File Type | .log | .fch |

| Calculation Type | FOPT | FTS |

| Calculation Method | RHF | RHF |

| Basis Set | 3-21G | 3-21G |

| Charge | 0 | 0 |

| Spin | Singlet | Singlet |

| E(RAM1)(a.u.) | -231.61518422 | -231.61932190 |

| RMS Gradient Norm (a.u.) | 0.00326607 | 0.00005539 |

| Imaginary Freq | ||

| Dipole Moment (debye) | 0.0017 | 0.0000 |

| Point Group | C1 | |

| DOI:10042/to-12611 10042/to-12611 | DOI:10042/to-12618 |

The imaginary frequency is -817.86 and is displayed below:

Both methods produced a nearly identical energy and imaginary frequency.

Optimising Boat Transition Structure

The QST2 method was used to find the boat transition structure. This method interpolates between a specified reactant and product to find the structure between the two.

The conformer of Anti 2 was used and the reactants and products numbered appropriately. If submitted the job fails because the molecules are not close enough to the transition state structure, and QST2 does not consider rotation around the central bonds. To solve this problem, the dihedral angles were altered as outlined below:

The central C-C-C-C dihedral angle to 0o.

The inside C-C-C to 100o.

The QST2 calculation then converged to the boat transition structure and one imaginary frequency of -839.73 was obtained.

| File Name | |

| File Type | .fch |

| Calculation Type | FREQ |

| Calculation Method | RHF |

| Basis Set | |

| Charge | 0 |

| Spin | Singlet |

| Total Energy (a.u.) | -231.60280227 |

| RMS Gradient Norm (a.u.) | 0.00003242 |

| Imaginary Freq | 1 |

| Dipole Moment (Debye) | 0.1583 |

| Point Group | |

| DOI:10042/to-12338 |

Comparison of "Chair" and "Boat"

On comparing chair and boat energies, it can be seen that the chair conformer is stable by approximately 10kcal/mol.

The Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate or IRC method was employed and the graphs are displayed below for comparison:

Boat

This graph contained 24 iterations, and the last point does not seem to be a minimum because the gradient of the graph has not become close to 0.

This graph had 51 iterations, and the gradient converged to 0, meaning a minimum was obtained. Having the force constant calculated at every iteration leads to a greater number of iterations and a lower energy being calculated.

Chair

Again using force constant set to always gives a lower energy. Comparing boat and chair, chair comes out as the most stable conformer in both methods.

The IRC were restarted and a larger number of points specified to obtain a minimum. This method gives more reliable energies but can sometimes lead to the wrong structure being computed if too many points are specified.

Chair - Points = 100

For chair, 100 points gave identical energies to using 50.

Boat- Points = 70

Increasing the points to 70 for boat gives the same energy for force constant once but force constant always gives a structure that seems to have veered off the path.

Comparison of Activation Energies

The chair and boat transition structures were reoptimised using the B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory and frequency calculations carried out. The HF/3-21G optimized structures were used as a starting point. The below table summarises the energies obtained and compares them to the energies of Anti 2 hexadiene. This enables Activation energy to be calculated and compared to experimental results.

| Anti 2 | Chair | Boat | Ea (Chair, kcal/mol) | Ea (Boat, kcal/mol) | Exp Ea Chair | Exp Ea Boat | |

| DOI:10042/to-12469 | DOI:10042/to-12472 | ||||||

| Total Energy | -234.611710 | -234.556983 | -234.543079 | 34.341905 | 43.066790 | ||

| Zero Point Energy | -234.469204 | -234.414929 | -234.402304 | 34.058032 | 41.980352 | 33.5 ± 0.5 | 44.7 ± 2.0 |

| Thermal Energy | -234.461857 | 234.409008 | 234.395970 | 33.163223 | 41.344685 |

The experimental value of Ea for chair is very close to the calculated, considering the error of ± 0.5, leaving a minimum difference of 0.058 kcl/mol. The experimental value for boat is also close, but has a minimum difference of 0.72 kcal/mol.

The Diels Alder Cycloaddition

The Diels Alder Cycloaddition is one of the most widely used techniques, giving stereo specific and regio controlled products is a pericyclic reaction in which a diene and a dienophile combine to give a six membered ring. [5]. In order for the reaction to occur, the reagents need to have orbitals with the same symmetry so that overlap of orbitals can occur. The reaction is also accelerated if the diene is electron donating and the dienophile electron withdrawing [5].

Optimising Diels Alder

The reaction between ethene and butadiene is an excellent example of a Diels Alder, and will be used to illustrate the above points. In order to compute its transition state, one must first optimise ethene and butadiene separately.

Ethene

Ethene was optimised using standard AM1 semi empirical methods: DOI:10042/to-12522

Butadiene

Optimisation

Butadiene was optimised using the AM1 semi-empirical method[6]:

Cis Butadiene has C2V symmetry and its HOMO is asymmetric with respect to its principle plane of symmetry and was chosen over trans because it gives a better orbital overlap.

The below picture shows the plane of symmetry present in the molecular orbitals:

The envelope

The transition state structure resembles an envelope with ethene approaching butadiene from above.

To optimise the structure the freeze bond method was applied. The first structure obatined by freezing the coordinates is here: DOI:10042/to-12420

The final structure of the transition state is here: DOI:10042/to-12421

The HOMO and LUMO of the transition structure are outlined below:

As you can see from the diagram, the HOMO consists of two σ-bonds formed through the overlap of the antisymmetric HOMO orbital of cis-butadiene with the antisymmetric LUMO of ethylene. The LUMO is formed of the symmetric HOMO of ethylene with the symmetric LUMO of cis-butadiene. This confirms the ideas outlined in the introduction and shows that the reaction is allowed because the orbitals have the correct symmetry.

The transition state has one imaginary frequency at -955.90cm -1 which corresponds to the transition state's synchronous formation of the two bonds, unlike the lowest positive frequency which is asynchronous.

The Reaction of Maleic Anhydride and 1, 3 Cyclohexadiene

This reaction will be used to find out which conformer, endo or exo, is the most stable, and the major product in the reaction.

Both Maleic Anhydride [7] and 1, 3 Cyclohexadiene [8] were optimised using HF/3-21G.

Both Maleic Anhydride [7] and 1, 3 Cyclohexadiene [8] were optimised using HF/3-21G.

The TS

In order to find the transition state of the reaction the freeze bond method was applied. First the co ordinates of the carbons where bond breaking and moaking would occur were frozen and the geometry optimised: DOI:10042/to-12461 . Then they were unfrozen and set to derivative, and the TS(Berny) optimisation selected. The following table displays the result:

Endo

| File Name | MA_derivativefrequency |

| File Type | .fch |

| Calculation Type | FREQ |

| Calculation Method | RAM1 |

| Basis Set | ZDO |

| Charge | 0 |

| Spin | Singlet |

| Total Energy (a.u.) | -0.05150479 |

| RMS Gradient Norm (a.u.) | 0.00000664 |

| Imaginary Freq | |

| Dipole Moment (Debye) | 6.1664 |

| Point Group | |

| DOI:10042/to-12458 |

A negative frequency at -806.42 cm -1 was found and the vibration corresponded to that of the transition state. TS imaginary frequency:

The above Jmol displays bond lengths between the C=C, C-C and Maleic Anhydride and 1, 3 Cyclohexadiene. Typical sp2-sp2 carbon double bond lengths are between 1.31 and 1.34A, and single sp3 to sp2 are of the order of 1.49 - 1.52A[9]. The double bond displayed is 1.39A which is more like that found in arenes, possibly alluding to the bond having aromatic character. The single bond is as expected at 1.49A. The distance between molecule 1 and 2 is 2.16A, which suggests it is not bonded yet. The van der waal radius of carbon is poorly defined but is believed to be in the region of 1.7-2.1A. The fitting of graphite suggests it is closest to 1.9A. [10] This suggests the the partly formed σ C-C bonds in the TS are just out of the van der waal radius, and are not quite bonded.

The two pictures below are the HOMO and LUMO of the transition state.

Both molecular orbitals are antisymmetric.

Exo

The other conformer was produced in the same way and the files are referenced [11] [12].

| opt derivative bond | |

| File Name | checkpoint_55865(1) |

| File Type | .fch |

| Calculation Type | FREQ |

| Calculation Method | RAM1 |

| Basis Set | ZDO |

| Charge | 0 |

| Spin | Singlet |

| Total Energy (a.u.) | -0.05041982 |

| RMS Gradient Norm (a.u.) | 0.00001951 |

| Imaginary Freq | 1 |

| Dipole Moment (Debye) | 5.5645 |

| Point Group |

A negative frequency at -812.28cm -1 was found and the vibration corresponded to that of the transition state.

TS imaginary frequency:

The above Jmol displays bond lengths between the C=C, C-C and Maleic Anhydride and 1, 3 Cyclohexadiene. As with the other conformer, the double bond is longer than expected at 1.39A. The single bond is also the same as in the other conformer. The distance between Maleic Anhydride and 1, 3 Cyclohexadiene is a little longer at 2.17A. This suggests the the partly formed σ C-C bonds in the TS are just out of the van der waal radius, and are not quite bonded.

Conclusion

Now that both conformers have been optimised we are able to conclude which is the most stable.

| Exo | Endo | |

| Total Energy (a.u.) | -0.05041982 | -0.05150479 |

As you can see from the table, the endo form is the most stable by 0.001085 Hartrees, which is 0.68 kcal/mol. This is most likely due to the exo structure suffering from steric strain between the carbonyl carbons and the 1, 3, cyclohexadiene ring. In addition, secondary orbital overlap accounts for the stability of the endo form. [13]. This can be observed n their molecular orbitals.

References

- ↑ James Ralph Hanson, Organic synthetic methods, 2002

- ↑ László Kürti, Barbara Czak, Strategic applications of named reactions in organic synthesis: background and Detailed Mechanisms, 2005

- ↑ Henry Rzepa, 2nd Year Course, Conformational Analysis

- ↑ P. Huber-Wälchli, Hs .H. Günthard, Volume 37, Issue 5, Pages 285–304, 1980

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Francesco Fringuelli, Aldo Taticch, The Diels-Alder reaction: selected practical methods, 1988

- ↑ https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:BUTA_FOR_OPT_jb.LOG

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-12422

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-12423

- ↑ Eric V. Anslyn, Dennis A. Doughert, Modern physical organic chemistry, 2006

- ↑ Victor Gold, Advances in physical organic chemistry, Volume 13, 1976

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-12556

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-12557

- ↑ M. Anne Fox, R. Cardona, and N. J. Kiwie, J . Org. Chem. 1987,52, 1469-1474