Rep:Mod:mod2ii108

Module 2: Bonding (Ab initio and density functional molecular orbital)

Irene Iriarte Carretero, October 2010

Introduction

In this section, computational chemistry is used to analyse the structures and bonding of several complexes. The use of computing can provide information about reactivity and about transition states that would be difficult to extract experimentally. Calculations can also provide things such as vibration analysis or NMR spectra. The final part of this section will prove how computing can help solve and understand certain aspects of inorganic chemistry. Gaussian was used to do all the calculations and Gaussview was used to visualise most of the results. However, the output files sometimes had to be directly examined in order to extract the information needed. The methods used determined the approximations made while solving the Schrodinger equation. The basis sets used determine the accuracy of the calculations, which also influences the time a calculation needs to take place.

BH3

Optimisation

The first task of this exercise was to optimise the geometry of a BH3 molecule. This was done using the B3LYP method and with a basis set of 3-21G. This section will also try to explain geometry optimisation in greater detail.

The first step was to draw the molecule and change all the B-H bond lengths to 1.50Å by using Gaussview. This was the starting point for the optimisation of the molecule geometry. The nuclei are assumed to fixed so only the electrons are taken into account (Born-Oppenheimer approximation). When the Schrodinger equation is solved, an energy is found which depends on the positions of the nuclei. However, if the nuclei move, the energy will be different because the interactions will be different. When the structure is optimised, the aim is to find the positions of the nuclei for which the energy is at a minimum. This is done by slightly moving the nuclei away from the starting point until the energy reaches its lowest point. This is the analysis of the Potential Energy Surface, which needs to be minimised.

This minimisation is done by finding the structure at which the first derivative of the Potential Energy Surface is equal to zero. This will occur when a change in position no longer causes a change in energy. If this does happen, the molecule is experiencing forces which means that the nuclei and electrons are not in equibrium. These forces will try to shift the nuclei and electrons into better and more favourable positions until a point is reached when the nuclei and electrons are in equilibrium and forces are no longer present.

This process can be seen through the analysis of different graphs provided by Gaussview. The first one shows the total energy curve, which clearly drops as the optimisation process develops. The second one is a plot of the RMS (Root Mean Square) Gradient, which approaches the desired value of zero as the energy lowers. Both these graphs show that the optimisation of the molecule was successful. However, a further test can be done, which consists in checking the text output file to make sure that all the necessary parameters have converged.

The final optimised molecule can be seen below. The bond lengths are now 1.20Å and the bond angles are 120°.

Frequency Analysis

A frequency analysis can be applied in order to see if the fact that the PES first derivative is zero means that the energy is indeed caused by a minimum and not by a transition state. It will be a minimum if the low frequencies are all positive. If one of the frequencies is negative, the structure is indeed a transition state, and if more than one of the frequencies are negative, the optimisation has not completed or it has not been successful.

This frequency analysis has to be performed using the same optimisation method and basis set because these determine how the molecule will be approached and analysed. If the frequency analysis takes place using a different basis set, different accuracies will be used, which will result in an incorrect result.

| Vibration number | Vibration | Frequency (cm-1) | Intensity | Symmetry |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

1144 | 93 | A' ' |

| 2 |  |

1204 | 12 | E' |

| 3 |  |

1204 | 12 | E' |

| 4 |  |

2598 | 0 | A ' |

| 5 |  |

2737 | 104 | E' |

| 6 |  |

2737 | 104 | E' |

Despite the fact that there are six vibrations, only three peaks can be seen on the IR spectrum. This is caused by two reasons. In the first place, the vibration at 2598cm-1 does not appear because it is not active on the IR as there is no change of dipole during the vibration. The second reason is that there are two sets of degenerate vibrations which share the frequencies.

NBO Analysis

NBO stands for Natural Bond Orbital and the analysis of this gives us information regarding, for example, hybridisation. The analysis separates the electron density of the molecule into atomic like orbitals, that then form two electron two centre bonds. The characteristics of these bonds can provide useful information about the molecule. For example, the information below shows how the molecule is neutral overall, as the negative charges in the hydrogen add up to the same positive charge of the boron.

Summary of Natural Population Analysis:

Natural Population

Natural -----------------------------------------------

Atom No Charge Core Valence Rydberg Total

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

B 1 0.33161 1.99903 2.66935 0.00000 4.66839

H 2 -0.11054 0.00000 1.11021 0.00032 1.11054

H 3 -0.11054 0.00000 1.11021 0.00032 1.11054

H 4 -0.11054 0.00000 1.11021 0.00032 1.11054

=======================================================================

* Total * 0.00000 1.99903 6.00000 0.00097 8.00000

The next set of data describe the hybridisation and different contributions in the bonds. For example, the second bond is between boron and hydrogen number 3. 44.5% of the bond comes from boron orbitals, which are hybridised by 33.3%s and 66.6%p. The rest of the bond comes from the hydrogen orbital, which is 100%s. In general, this means that boron forms three sp2 orbitals. Each of them interacts with an s orbital from each hydrogen.

(Occupancy) Bond orbital/ Coefficients/ Hybrids

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1. (1.99853) BD ( 1) B 1 - H 2

( 44.48%) 0.6669* B 1 s( 33.33%)p 2.00( 66.67%)

0.0000 0.5774 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

0.8165 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

( 55.52%) 0.7451* H 2 s(100.00%)

1.0000 0.0000

2. (1.99853) BD ( 1) B 1 - H 3

( 44.48%) 0.6669* B 1 s( 33.33%)p 2.00( 66.67%)

0.0000 0.5774 0.0000 0.7071 0.0000

-0.4082 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

( 55.52%) 0.7451* H 3 s(100.00%)

1.0000 0.0000

3. (1.99853) BD ( 1) B 1 - H 4

( 44.48%) 0.6669* B 1 s( 33.33%)p 2.00( 66.67%)

0.0000 0.5774 0.0000 -0.7071 0.0000

-0.4082 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

( 55.52%) 0.7451* H 4 s(100.00%)

1.0000 0.0000

4. (1.99903) CR ( 1) B 1 s(100.00%)

1.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

5. (0.00000) LP*( 1) B 1 s(100.00%)

MO Analysis

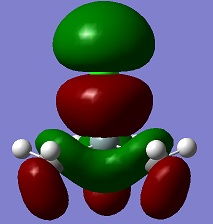

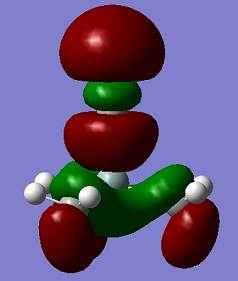

Computing is a useful tool regarding molecular orbitals, as it helps us visualise the distribution of the electron density. This can be observed when analysing the molecular orbitals of BH3. In fact, this can be used to compare to the less accurate analysis done when drawing an MO diagram. This diagram can be seen below and will then be used to compare the accuracy between the two methods. (Link to repository: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-5529)

The table below shows how the computationally calculated molecular orbitals relate to the orbitals drawn in the diagram. The first orbital does not have an equivalent, because the diagram only takes into account the valence electrons and their orbitals. However, the boron 1s orbital lies too low in energy to interact. One can see how the molecular orbital diagram shows the shape of the calculated molecular orbitals in quite an accurate way, and we can therefore confidently use it to obtain an approximate idea of the shape and geometries of the orbitals and rationalise its reactivity.

| MO number | Computational MO | Diagram MO | Symmetry |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

1a'1 | |

| 2 |  |

|

2a'1 |

| 3 |  |

|

1e' |

| 4 |  |

|

1e' |

| 5 |  |

|

1a2 |

| 6 |  |

|

3a'1 |

| 7 |  |

|

2e' |

| 8 |  |

|

2e' |

Analysis of TlBr3

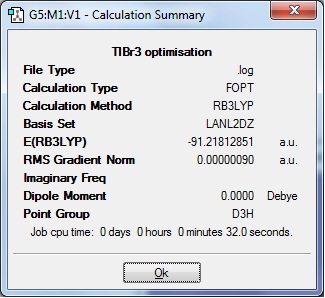

The aim of this section is to optimise the energy of the ground state structure of a TlBr3 molecule in order to later carry out a frequency analysis. The molecule has a D3h symmetry and this was set as a constraint with a very high tolerance. It was then minimised using Gaussian, through B3LYP and a basis-set of LanL2DZ. The summary of this optimisation can be found below.

In order to check that the energy was a minimum and that the optimisation had indeed completed successfully, a frequency analysis had to be performed. This frequency analysis shows the second derivative of the potential energy surface, and therefore tells us whether we are at an energy minimum. This happens when the frequencies are all positive. However, if there is a negative frequency the structure corresponds to the transition state. Finally, if there are more negative frequencies we can conclude that the optimisation has not completed or has not worked. The frequencies below show that all frequencies are close to being positive, and the reason why some are slightly negative is the error produced by using a low level method.

| Low frequencies | -3.4 | -0.0026 | -0.0004 | 0.0015 | 3.9 | 3.9 |

| Normal frequencies | 46 | 46 | 52 | 165 | 211 | 211 |

The Tl-Br bond length in the optimised molecule is 2.65 Å which is in agreement with the literature value of 2.51 Å [1]. The angle between the bromides is of 120°. (Link to the repository: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-5528)

In some structures, Gaussview does not draw bonds in where we expect. However, this does not mean that there isn't a bond. The bonds do not appear because Gaussview uses a cutoff distance; if the distance between the atoms is greater than this, a bond will not be drawn. A bond can be said to exist between two atoms when the forces between them are sufficiently strong to hold the atoms together in a stable unit.

Isomers of Mo(CO)4L2

In this section, the characteristics of the trans and cis isomers of Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2. This study is based on the Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2 molecules, where the phenyl groups had to be changed for chlorides, in order to reduce the computational time needed for the calculations. The main aim of this section is to discover the differences between the trans and the cis isomers, with respect to their vibrations and their thermodynamic properties.

The molecules were optimised using the B3LYP method and a low level basis set (LANL2MB). This was done in order to get a rough idea of the optimised geometry. Loose convergence criteria was also applied so the calculations are allowed to converge by being able to reach the limits needed.

This initial optimisation was then changed to make sure that the minimum found was the correct one. This depends on the torsion angles between the CO group and the Cl. For the cis isomer, the torsion angles were set to be 0 and 180°. For the trans isomer, the most stable structure is one in which the PCl3 groups are eclipsed and one Cl lies parallel to an Mo-C bond. This final structure was optimised once again using a better pseudo-potential (LANL2DZ) now that the geometry was roughly right. A much tighter convergence criteria had to therefore be used.

The final structures can be seen below, along with their optimisation files.

A frequency analysis was then performed on each isomer in order to check whether the structures were indeed optimised and therefore had a minimum energy. As can be seen from the table below, the low frequencies were close enough to zero to assume that the geometries were optimised. The negative values can be explained due to numerical difficulties.

trans isomer low frequencies: -2.2417 -1.7132 0.0004 0.0006 0.0007 1.8193 cis isomer low frequencies: -1.7479 0.0004 0.0007 0.0007 1.0498 1.4896

The table below compares the calculated bond lengths for the trans complex with their literature value. In this case, all the Mo-C bond lengths are almost identical, due to the symmetry of the molecule. A table with the angles is also shown. http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-5328

|

|

The table below does the same as above, but for the cis isomer. In this case, one can see that, for example, Mo-C bonds are not always the same. This is due to the lower symmetry of the molecule with respect to the trans isomer. http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-5337

|

|

Comparing the two sets of data, one can conclude that the cis isomer is further away from the ideal octahedral geometry than the trans isomer, as can be seen from the deviated angles, which are more deviated from ideality in the literature values than in the calculated ones. However, in general, one can see that the computational results agree with the literature values to a reasonable degree. The fact that the literature values are not for the exact molecules also has to be taken into account. For example, the angle between P(2)-Mo-P(3) is larger in literature than in the molecule examined because the phenyl groups present a bigger steric problem than the chlorides, pushing the two phosphorus atoms apart and the two CO groups closer together. This shows how the molecule can be tuned in order to get the reactivity and the structure needed for many processes. Therefore, smaller substituents on the phosphorus atoms will give more stable cis isomers. For example, when the substituents are methyl groups, the cis isomer will isomerise completely to the trans isomer. [4] Looking at the energies, the trans isomer has a slightly lower energy than the cis one because of its less strained angles and interactions between the two PCl3 groups. The trans complex has an energy of -623.576 a.u. (-1637198.91 kJ/mol) and the energy of the cis isomer is -623.577 a.u. (-1637201.54 kJ/mol). This is taking a large number of decimal places into account, as if one uses the accuracy recommended, the energies are the same. Therefore, the cis isomer is 2.63 kJ/mol higher in energy than the trans isomer, which is not very significant.

The IR spectra of the two molecules were examined and the results were rationalised. Less peaks appeared for the trans isomer than for the cis isomer. This is due to the fact that the trans isomer has a higher symmetry than the cis isomer, and therefore a lot of the vibrations do not result in a change of dipole moment, therefore not producing a peak. However, this does not happen in the cis isomer, as most vibrations produce a change in the dipole moment.

The peaks that illustrate this better are the C=O stretches. The cis isomer gives four peaks at frequencies at around 1950 cm-1 while the trans isomer only gives one peak. This can be explained by looking at an example of a vibration in each complex. In this vibration, the CO groups stretch in an asymmetric fashion. In the cis isomer, this results in a change of dipole, but it does not happen in the trans. This also happens in other vibrations.

| Isomer | Vibration | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| trans |  |

1958 |

| C(13)-Mo-C(10) |  |

1977 |

Miniproject: Pseudohalogens

Introduction

Pseudohalogens are certain inorganic compounds such as a cyanide and a thiocyanate, which show similar properties to halogens, such as existing as dimers and forming molecular compounds with non metals and ionic compounds with alkali metals. In this section, four molecules will be studied. These are Me3SiCl, Me3SiBr, Me3SiCN and Me3SCN. A deeper analysis of Me3SiCN will be done.

Optimisation and geometry

The first step of the project was to optimise the energies of the molecules. This was done using B3LYP method with a 6-311g(d,p) basis set. Below is a table showing the values of the bond lengths. In general, they agree with the general typical bond lengths.

| Molecule | Si-C | Si-Cl | Si-Br | C-N | Si-S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 188 | 209 | ||||

| 188 | 228 | ||||

| 188 | 116 | ||||

| 188 | 116 | 170 |

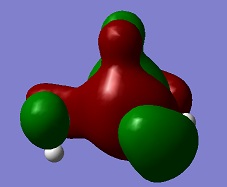

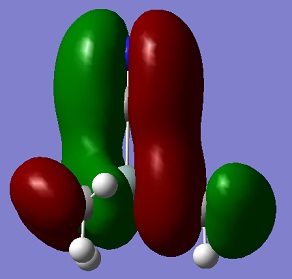

Analysis of Molecular Orbitals

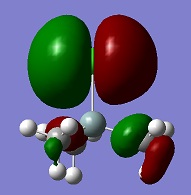

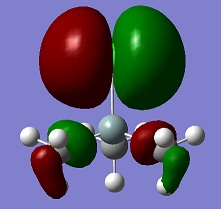

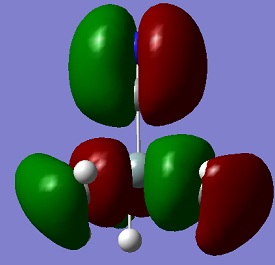

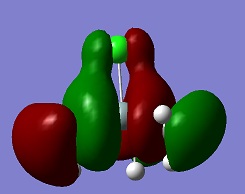

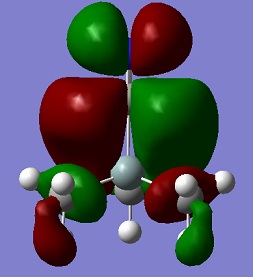

An aim of this project was to compare the Molecular Orbitals of Me3SiCl with the Molecular Orbitals of Me3SiCN in order to analyse if they were similar and to therefore confirm that CN bonds to molecules in a similar manner as Cl. The molecular orbitals chosen were mostly the occupied ones where the orbitals of CN and Cl were heavily involved. This can be seen in the table below. The results show that the molecular orbitals are indeed very similar for the occupied orbitals, but not for the LUMO.

Si-C bonds are very stable due to their low polarity, but Si-X bonds are much more reactive. The molecular orbitals show that CN groups show orbitals of the same bonding and anti-bonding characteristics as a Cl group, which means that CN is correctly called a pseudohalogen as it will show similar reactivity.

| Orbital | Me3SiCl | Me3SiCN |

|---|---|---|

| HOMO |  |

|

| HOMO -1 |  |

|

| HOMO -2 |  |

|

| HOMO -3 |  |

|

| HOMO -4 |  |

|

| LUMO |  |

|

Analysis of IR spectra

The IR spectra of these molecules were also calculated and can be seen below. From these spectra, one can see how Me3SiSCN has the highest number of peaks, and this is because there are extra vibrations coming from the SCN group and because this molecule is less symmetrical than the other three. A peak appears in Me3SiSCN and Me3SiCN due to a stretching of the CN group. This obviously does not appear in the other two molecules. However, the other two molecules show a stronger vibration at approximately 477cm-1, which corresponds to the stretching of the Si-X bond. The largest peak in all the molecules corresponds to the bending of the hydrogen molecules in the methyl groups at 881cm-1. In general, the common vibrations don't show a significant shift for the different molecules.

|

|

|

|

A summary of the most important vibrations can be seen below.

| Vibration | Frequency (cm-1) |

|---|---|

|

477 |

|

884 |

|

2269 |

|

1297 |

Conclusion

In conclusion, one can say that the aim of the project was achieved, as pseudohalogens were successfully compared with actual halogens, by looking at their MOs. The IR spectra were also analysed. In general, computational techniques are a good way of understanding and analysing reactions and molecules. Computing can be used to rationalise structures, even ones which would be very difficult to analyse experimentally. The previous exercises have shown that bond lengths, angles and energies are predicted to a reasonable degree by comparing the values to literature values.

References

- ↑ J. Glaser and G. Johansson, Acta Chemica Scandinava, 1982, 36, 125-135. DOI:10.3891/acta.chem.scand.36a-0125

- ↑ G. Hogarth and T. Norman, Inorganica Chimica Acta,1997, 254(1), 167-171

- ↑ F. Albert Cotton, Donald J. Darensbourg, Simonetta Klein, and Brian W. S. Kolthammer, Inorg. Chem., 21, (1982), p294-299

- ↑ D. J. Darensbourg, Inorg. Chem., 1979, 18, 14-17