Rep:Mod:mod1 aal109

Module 1: Structure and Spectroscopy

The molecular structure and reactivity of chemical compounds can be investigated using a myriad of computational methods. Quantum chemical methods begins by solving, to various degrees of sophistication, the Schrodinger's equation for the chemical species. The molecular mechanics method, on the other hand, avoids numerical solution of the Schrodinger's equation by treating chemical bonds as springs and thus applying Newtonian mechanics to describe chemical systems.

Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

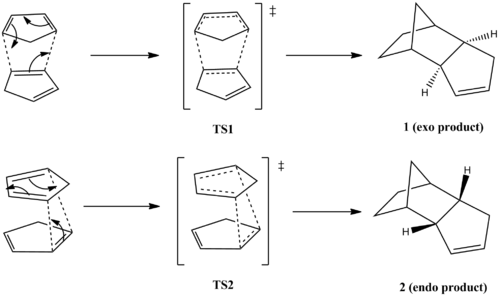

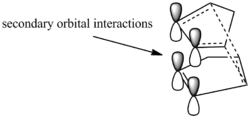

Cyclopentadiene readily dimerises at room temperature via [4+2] Diels-Alder cycloaddition. The reaction can proceed to form the diastereomeric exo product (1) or the endo product (2). Experimentally, the endo product is formed in favour of the exo product. Historically, Alder [1] proposed that endo addition was the consequence of a plane-to-plane orientation of diene and dienophile, using the term "maximum accumulation of double bonds" to describe endo selectivity. Using Frontier Orbital Theory, Woodward and Hoffman [2] rationalised the endo selectivity due to secondary orbital overlap in TS2 which is absent in TS1.

In order to investigate the relative energy of the products, molecular mechanics method is used with the Allinger MM2 forcefield, which is shown to accurately predict conformations of simple hydrocarbons [3].

exo-Cyclopentadiene dimer endo-Cyclopentadiene dimer

Stretch: 1.2851 1.2515 Bend: 20.5806 20.8486 Stretch-Bend: -0.8380 -0.8358 Torsion: 7.6559 9.5106 Non-1,4 VDW: -1.4177 -1.5434 1,4 VDW: 4.2331 4.3184 Dipole/Dipole: 0.3777 0.4475 Total Energy: 31.8765 kcal/mol 33.9975 kcal/mol

Endo Product |

exo-Cyclopentadiene dimer optimised using MM2

Exo Product |

endo-Cyclopentadiene dimer optimised using MM2

From MM2 calculations, the exo product is thermodynamically more stable than the endo product due to the torsional strain. The MM2 forcefield models torsional strain by three simple cosine function of the dihedral angles. Analyzing the structure of the two isomers reveals the particularly unfavourable dihedral angles between the cyclopentene ring and the bridge in the endo isomer which are alleviated in the exo case.

exo-Cyclopentadiene dimer endo-Cyclopentadiene dimer

C(4)-C(5)-C(6)-C(10) 178.6o 45.8o C(1)-C(2)-C(3)-C(8) 177.3o 51.1o

The hydrogenation of the the endo cyclopentadiene dimer affords either isomer 3 or 4, depending on the position of the C=C bond being hydrogenated.

isomer 3 |

Isomer 3 optimised using MM2

Exo Product |

Isomer 4 optimised using MM2

Comparing the relative energies between the isomers reveals '4 being the more stable isomer.

Isomer 3 Isomer 4

Stretch: 1.2777 1.0972 Bend: 19.8599 14.5234 Stretch-Bend: -0.8343 -0.5495 Torsion: 10.8108 12.4973 Non-1,4 VDW: -1.2236 -1.0698 1,4 VDW: 5.6324 4.5128 Dipole/Dipole: 0.1621 0.1406 Total Energy: 35.6850 kcal/mol 31.1520 kcal/mol

The energies displayed by the MM2 forcefield suggests that the bending energy is the main cause of the energy difference between the two isomers. Comparing the bond angles shows that the bridge C(2)-C(7)-C(5) is the most strained bond angle in both isomers. This rationalised the high bend energy in isomer 3 - the bridge constrains the six membered ring, and therefore it is more favourable to have all sp3 carbon centres, which has lower equilibrium bond angle, in the six membered ring rather than sp2 carbons, which has larger equilibrium bond angle. In fact, table below shows the bond angles C(4)-C(5)-C(7), C(1)-C(2)-C(7), C(5)-C(4)-C(1) and C(2)-C(1)-C(4) in isomer 3 being the most strained angles.

| Atoms | θideal | θopmised | abs(θideal-θoptimised) |

|---|---|---|---|

| H(22)-C(9)-C(8) | 109.41 | 109.6367 | 0.2267 |

| H(22)-C(9)-C(10) | 109.41 | 109.6368 | 0.2268 |

| H(21)-C(9)-C(8) | 109.41 | 112.7539 | 3.3439 |

| H(21)-C(9)-C(10) | 109.41 | 112.7525 | 3.3425 |

| C(8)-C(9)-C(10) | 109.5 | 103.4546 | 6.0454 |

| H(24)-C(10)-H(23) | 109.4 | 107.8198 | 1.5802 |

| H(24)-C(10)-C(6) | 109.41 | 111.341 | 1.931 |

| H(24)-C(10)-C(9) | 109.41 | 109.0414 | 0.3686 |

| H(23)-C(10)-C(6) | 109.41 | 112.5986 | 3.1886 |

| H(23)-C(10)-C(9) | 109.41 | 112.6827 | 3.2727 |

| C(6)-C(10)-C(9) | 109.5 | 103.3286 | 6.1714 |

| H(19)-C(8)-C(9) | 109.41 | 112.6854 | 3.2754 |

| H(19)-C(8)-C(3) | 109.41 | 112.5984 | 3.1884 |

| H(19)-C(8)-H(20) | 109.4 | 107.8199 | 1.5801 |

| C(9)-C(8)-C(3) | 109.5 | 103.3298 | 6.1702 |

| C(9)-C(8)-H(20) | 109.41 | 109.0366 | 0.3734 |

| C(3)-C(8)-H(20) | 109.41 | 111.3419 | 1.9319 |

| H(11)-C(6)-C(10) | 109.39 | 109.5632 | 0.1732 |

| H(11)-C(6)-C(5) | 109.39 | 109.8504 | 0.4604 |

| H(11)-C(6)-C(3) | 109.39 | 109.6047 | 0.2147 |

| C(10)-C(6)-C(5) | 109.51 | 117.8704 | 8.3604 |

| C(10)-C(6)-C(3) | 109.51 | 106.2665 | 3.2435 |

| C(5)-C(6)-C(3) | 109.51 | 103.2501 | 6.2599 |

| H(18)-C(7)-H(17) | 109.4 | 108.7325 | 0.6675 |

| H(18)-C(7)-C(2) | 109.41 | 113.6743 | 4.2643 |

| H(18)-C(7)-C(5) | 109.41 | 113.677 | 4.267 |

| H(17)-C(7)-C(2) | 109.41 | 113.2932 | 3.8832 |

| H(17)-C(7)-C(5) | 109.41 | 113.2913 | 3.8813 |

| C(2)-C(7)-C(5) | 109.5 | 93.6869 | 15.8131 |

| C(6)-C(3)-C(8) | 109.51 | 106.2603 | 3.2497 |

| C(6)-C(3)-H(12) | 109.39 | 109.6031 | 0.2131 |

| C(6)-C(3)-C(2) | 109.51 | 103.2523 | 6.2577 |

| C(8)-C(3)-H(12) | 109.39 | 109.5661 | 0.1761 |

| C(8)-C(3)-C(2) | 109.51 | 117.8726 | 8.3626 |

| H(12)-C(3)-C(2) | 109.39 | 109.8501 | 0.4601 |

| C(6)-C(5)-C(4) | 109.51 | 109.1775 | 0.3325 |

| C(6)-C(5)-H(16) | 109.39 | 116.6919 | 7.3019 |

| C(6)-C(5)-C(7) | 109.51 | 100.0777 | 9.4323 |

| C(4)-C(5)-H(16) | 109.39 | 115.2335 | 5.8435 |

| C(4)-C(5)-C(7) | 109.51 | 97.9309 | 11.5791 |

| H(16)-C(5)-C(7) | 109.39 | 115.2255 | 5.8355 |

| H(14)-C(2)-C(1) | 109.39 | 115.2341 | 5.8441 |

| H(14)-C(2)-C(7) | 109.39 | 115.2224 | 5.8324 |

| H(14)-C(2)-C(3) | 109.39 | 116.6942 | 7.3042 |

| C(1)-C(2)-C(7) | 109.51 | 97.9307 | 11.5793 |

| C(1)-C(2)-C(3) | 109.51 | 109.1744 | 0.3356 |

| C(7)-C(2)-C(3) | 109.51 | 100.0809 | 9.4291 |

| H(15)-C(4)-C(5) | 118.2 | 125.1839 | 6.9839 |

| H(15)-C(4)-C(1) | 120 | 127.024 | 7.024 |

| C(5)-C(4)-C(1) | 122 | 107.7677 | 14.2323 |

| H(13)-C(1)-C(2) | 118.2 | 125.1829 | 6.9829 |

| H(13)-C(1)-C(4) | 120 | 127.0262 | 7.0262 |

| C(2)-C(1)-C(4) | 122 | 107.7664 | 14.2336 |

| Atoms | θideal | θopmised | abs(θideal-θoptimised) |

|---|---|---|---|

| H(26)-C(4)-H(25) | 109.4 | 107.3037 | 2.0963 |

| H(26)-C(4)-C(5) | 109.41 | 109.9046 | 0.4946 |

| H(26)-C(4)-C(1) | 109.41 | 110.4047 | 0.9947 |

| H(25)-C(4)-C(5) | 109.41 | 113.3837 | 3.9737 |

| H(25)-C(4)-C(1) | 109.41 | 112.5545 | 3.1445 |

| C(5)-C(4)-C(1) | 109.5 | 103.2923 | 6.2077 |

| H(18)-C(7)-H(17) | 109.4 | 109.3885 | 0.0115 |

| H(18)-C(7)-C(2) | 109.41 | 113.3877 | 3.9777 |

| H(18)-C(7)-C(5) | 109.41 | 113.7253 | 4.3153 |

| H(17)-C(7)-C(2) | 109.41 | 113.5395 | 4.1295 |

| H(17)-C(7)-C(5) | 109.41 | 113.4899 | 4.0799 |

| C(2)-C(7)-C(5) | 109.5 | 92.5914 | 16.9086 |

| H(15)-C(1)-H(13) | 109.4 | 107.3746 | 2.0254 |

| H(15)-C(1)-C(4) | 109.41 | 113.2092 | 3.7992 |

| H(15)-C(1)-C(2) | 109.41 | 113.1442 | 3.7342 |

| H(13)-C(1)-C(4) | 109.41 | 110.6665 | 1.2565 |

| H(13)-C(1)-C(2) | 109.41 | 109.9602 | 0.5502 |

| C(4)-C(1)-C(2) | 109.5 | 102.4772 | 7.0228 |

| C(4)-C(5)-C(6) | 109.51 | 112.701 | 3.191 |

| C(4)-C(5)-H(16) | 109.39 | 113.2524 | 3.8624 |

| C(4)-C(5)-C(7) | 109.51 | 101.2097 | 8.3003 |

| C(6)-C(5)-H(16) | 109.39 | 112.9001 | 3.5101 |

| C(6)-C(5)-C(7) | 109.51 | 100.8223 | 8.6877 |

| H(16)-C(5)-C(7) | 109.39 | 114.8058 | 5.4158 |

| H(11)-C(6)-C(10) | 109.39 | 109.8646 | 0.4746 |

| H(11)-C(6)-C(5) | 109.39 | 108.4671 | 0.9229 |

| H(11)-C(6)-C(3) | 109.39 | 110.5562 | 1.1662 |

| C(10)-C(6)-C(5) | 109.51 | 117.7854 | 8.2754 |

| C(10)-C(6)-C(3) | 109.51 | 107.9335 | 1.5765 |

| C(5)-C(6)-C(3) | 109.51 | 101.9035 | 7.6065 |

| C(1)-C(2)-H(14) | 109.39 | 113.0761 | 3.6861 |

| C(1)-C(2)-C(7) | 109.51 | 101.1477 | 8.3623 |

| C(1)-C(2)-C(3) | 109.51 | 111.2859 | 1.7759 |

| H(14)-C(2)-C(7) | 109.39 | 115.2932 | 5.9032 |

| H(14)-C(2)-C(3) | 109.39 | 113.287 | 3.897 |

| C(7)-C(2)-C(3) | 109.51 | 101.6253 | 7.8847 |

| C(9)-C(10)-H(24) | 109.41 | 112.5309 | 3.1209 |

| C(9)-C(10)-H(23) | 109.41 | 108.4392 | 0.9708 |

| C(9)-C(10)-C(6) | 109.5 | 102.8864 | 6.6136 |

| H(24)-C(10)-H(23) | 109.4 | 108.5118 | 0.8882 |

| H(24)-C(10)-C(6) | 109.41 | 112.9324 | 3.5224 |

| H(23)-C(10)-C(6) | 109.41 | 111.4184 | 2.0084 |

| C(8)-C(3)-C(6) | 109.51 | 103.1737 | 6.3363 |

| C(8)-C(3)-H(12) | 109.39 | 110.194 | 0.804 |

| C(8)-C(3)-C(2) | 109.51 | 116.3877 | 6.8777 |

| C(6)-C(3)-H(12) | 109.39 | 111.4882 | 2.0982 |

| C(6)-C(3)-C(2) | 109.51 | 103.4393 | 6.0707 |

| H(12)-C(3)-C(2) | 109.39 | 111.6178 | 2.2278 |

| H(20)-C(9)-C(10) | 118.2 | 122.5729 | 4.3729 |

| H(20)-C(9)-C(8) | 120 | 124.3662 | 4.3662 |

| C(10)-C(9)-C(8) | 122 | 113.0437 | 8.9563 |

| H(19)-C(8)-C(9) | 120 | 124.8576 | 4.8576 |

| H(19)-C(8)-C(3) | 118.2 | 122.7122 | 4.5122 |

| C(9)-C(8)-C(3) | 122 | 112.4301 | 9.5699 |

Rationalising the outcome of the reaction in terms of thermodynamic control and kinetic control, the Diels-Alder reaction is kinetically controlled as the thermodynamically most stable product is not formed. Rather, it is the activation barrier, and the energy of the transition state, that determines the selectivity. As the endo transition state benefit from secondary orbital overlap, it is stabilised relative to exo thus the endo isomer is formed in preference to exo.

If the hydrogenation proceeds via thermodynamic control, isomer 4 will be formed in preference of isomer 3 as it has lower energy.

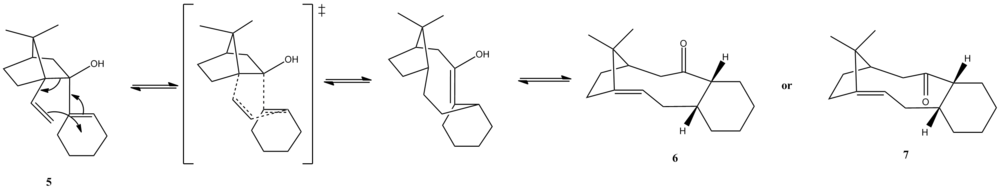

Stereochemistry and Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

Atropisomerism is a type of stereoisomerism that may arise in systems where free rotation about a single covalent bond is impeded sufficiently so as to allow different stereoisomers to be separated. A key intermediate in the synthesis of Taxol [4] purposed by Elmore and Paquette involves atropisomeric carbonyl species 6 and 7 formed by a reversible [3,3] sigmatropic (oxy-cope) rearrangement on the precursor 5. In the case 6 and 7, it is the restricted rotation about C-C single bonds in which the carbonyl group is attached to that hinders the interconversion between the two species. The orientation of the carbonyls has great impact as to the stereochemistry of carbonyl addition.

The the oxy-cope rearragement is reversible, the reaction is thus under thermodynamic control and the relative energy of the products determines the relative abundance of the products. Using the MM2 and MMFF94 forcefield, the geometry of the products were optimised. There are stable conformers with the six-membered ring having chair (6/7) or twist-boat ( 6' / 7' )conformation, with the chair conformers having the lowest energy.

isomer 3 |

Isomer 6 optimised using MM2

Exo Product |

Isomer 6' optimised using MM2

isomer 3 |

Isomer 7 optimised using MM2

Exo Product |

Isomer 7' optimised using MM2

Energies of the atropisomer 6, 6' , 7 and 7' calculated with the MM2 forcefield

Atropisomer 6 Atropisomer 6' Atropisomer 7 Atropisomer 7' Stretch: 2.7848 2.9455 2.6204 2.7036 Bend: 16.5411 17.2176 11.3390 11.8271 Stretch-Bend: 0.4305 0.5017 0.3431 0.3916 Torsion: 18.2516 21.2783 19.6745 22.8850 Non-1,4 VDW: -1.5535 -1.4165 -2.1641 -1.9929 1,4 VDW: 13.1098 14.5082 12.8723 14.3404 Dipole/Dipole: -1.7247 -1.7304 -2.0023 -1.9969 Total Energy: 47.8395 kcal/mol 53.3044 kcal/mol 33.9975 kcal/mol 48.1580 kcal/mol

Unsurprisingly, the twistboat conformers have far higher torsional energy and van der Waal repulsion than the cyclohexane conformer. That is because of fact that the twistboat conformation deviates from the ideal conformation of all C-H staggering with respect to each other (torsional strain) and some "flagpole" interaction (van der Waal repulsion). Comparing the two atropisomers, 7 is more stable than 6, with the bend term driving this difference in energy. Looking at the bond angles, the most strained angle in the molecule C(11)-C(17)-C(14), which is the 3 carbon bridge common to both isomers. However, the angles near the carbonyl group at C(6), C(11)-C(1)-C(6) and C(10)-C(5)-C(6), in 6 deviates significantly from the ideal geometry.

| Atoms | θideal | θoptimised (6) | abs(θideal-θoptimised(6)) | θoptimised (7) | abs(θideal-θoptimised(7)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H(44)-C(19)-H(42) | 109 | 105.4098 | 3.5902 | 106.7242 | 2.2758 |

| H(44)-C(19)-C(17) | 110 | 111.0122 | 1.0122 | 110.8557 | 0.8557 |

| H(43)-C(19)-H(42) | 109 | 106.8011 | 2.1989 | 106.117 | 2.883 |

| H(43)-C(19)-C(17) | 110 | 110.5491 | 0.5491 | 110.5488 | 0.5488 |

| H(42)-C(19)-C(17) | 110 | 114.9696 | 4.9696 | 114.4825 | 4.4825 |

| H(41)-C(18)-H(40) | 109 | 106.6511 | 2.3489 | 106.8102 | 2.1898 |

| H(41)-C(18)-H(39) | 109 | 105.6436 | 3.3564 | 106.4907 | 2.5093 |

| H(41)-C(18)-C(17) | 110 | 114.7988 | 4.7988 | 114.164 | 4.164 |

| H(40)-C(18)-H(39) | 109 | 107.6517 | 1.3483 | 107.2308 | 1.7692 |

| H(40)-C(18)-C(17) | 110 | 111.0568 | 1.0568 | 111.4194 | 1.4194 |

| H(39)-C(18)-C(17) | 110 | 110.6428 | 0.6428 | 110.36 | 0.36 |

| H(36)-C(12)-H(35) | 109.4 | 105.3315 | 4.0685 | 105.4331 | 3.9669 |

| H(36)-C(12)-C(13) | 109.41 | 113.0536 | 3.6436 | 113.5416 | 4.1316 |

| H(36)-C(12)-C(11) | 109.41 | 112.5113 | 3.1013 | 113.1331 | 3.7231 |

| H(35)-C(12)-C(13) | 109.41 | 109.8997 | 0.4897 | 110.6385 | 1.2285 |

| H(35)-C(12)-C(11) | 109.41 | 110.9103 | 1.5003 | 110.3879 | 0.9779 |

| C(13)-C(12)-C(11) | 109.5 | 105.2287 | 4.2713 | 103.8196 | 5.6804 |

| H(34)-C(11)-C(17) | 109.39 | 108.6517 | 0.7383 | 108.9641 | 0.4259 |

| H(34)-C(11)-C(12) | 109.39 | 108.4769 | 0.9131 | 110.7351 | 1.3451 |

| H(34)-C(11)-C(1) | 109.39 | 107.0812 | 2.3088 | 108.0671 | 1.3229 |

| C(17)-C(11)-C(12) | 109.51 | 103.949 | 5.561 | 103.4 | 6.11 |

| C(17)-C(11)-C(1) | 109.51 | 117.5102 | 8.0002 | 115.8812 | 6.3712 |

| C(12)-C(11)-C(1) | 109.51 | 110.8969 | 1.3869 | 109.7346 | 0.2246 |

| H(31)-C(9)-H(30) | 109.4 | 106.8601 | 2.5399 | 106.7353 | 2.6647 |

| H(31)-C(9)-C(10) | 109.41 | 109.7135 | 0.3035 | 109.7721 | 0.3621 |

| H(31)-C(9)-C(8) | 109.41 | 109.5067 | 0.0967 | 109.6941 | 0.2841 |

| H(30)-C(9)-C(10) | 109.41 | 109.9431 | 0.5331 | 110.2294 | 0.8194 |

| H(30)-C(9)-C(8) | 109.41 | 109.8405 | 0.4305 | 109.9163 | 0.5063 |

| C(10)-C(9)-C(8) | 109.5 | 110.8904 | 1.3904 | 110.4229 | 0.9229 |

| H(29)-C(8)-H(28) | 109.4 | 106.5504 | 2.8496 | 107.0457 | 2.3543 |

| H(29)-C(8)-C(9) | 109.41 | 109.6512 | 0.2412 | 109.5554 | 0.1454 |

| H(29)-C(8)-C(7) | 109.41 | 109.719 | 0.309 | 109.5574 | 0.1474 |

| H(28)-C(8)-C(9) | 109.41 | 109.6095 | 0.1995 | 109.9209 | 0.5109 |

| H(28)-C(8)-C(7) | 109.41 | 110.2788 | 0.8688 | 109.9403 | 0.5303 |

| C(9)-C(8)-C(7) | 109.5 | 110.9327 | 1.4327 | 110.7458 | 1.2458 |

| H(22)-C(1)-H(21) | 109.4 | 103.0874 | 6.3126 | 103.5883 | 5.8117 |

| H(22)-C(1)-C(11) | 109.41 | 105.2772 | 4.1328 | 111.2507 | 1.8407 |

| H(22)-C(1)-C(6) | 108.8 | 104.9172 | 3.8828 | 110.0484 | 1.2484 |

| H(21)-C(1)-C(11) | 109.41 | 110.1627 | 0.7527 | 106.7866 | 2.6234 |

| H(21)-C(1)-C(6) | 108.8 | 108.1892 | 0.6108 | 104.9874 | 3.8126 |

| C(11)-C(1)-C(6) | 110 | 123.2158 | 13.2158 | 118.8102 | 8.8102 |

| H(33)-C(10)-H(32) | 109.4 | 107.5321 | 1.8679 | 106.3708 | 3.0292 |

| H(33)-C(10)-C(5) | 109.41 | 110.8112 | 1.4012 | 109.1125 | 0.2975 |

| H(33)-C(10)-C(9) | 109.41 | 108.8812 | 0.5288 | 108.2338 | 1.1762 |

| H(32)-C(10)-C(5) | 109.41 | 110.2613 | 0.8513 | 110.0196 | 0.6096 |

| H(32)-C(10)-C(9) | 109.41 | 107.7952 | 1.6148 | 109.8895 | 0.4795 |

| C(5)-C(10)-C(9) | 109.5 | 111.4288 | 1.9288 | 112.9802 | 3.4802 |

| O(20)-C(6)-C(1) | 122.5 | 118.4582 | 4.0418 | 120.2299 | 2.2701 |

| O(20)-C(6)-C(5) | 122.5 | 115.7227 | 6.7773 | 119.9971 | 2.5029 |

| C(1)-C(6)-C(5) | 116.6 | 125.6134 | 9.0134 | 119.7169 | 3.1169 |

| H(27)-C(7)-H(26) | 109.4 | 106.2979 | 3.1021 | 106.4414 | 2.9586 |

| H(27)-C(7)-C(8) | 109.41 | 109.9789 | 0.5689 | 109.0949 | 0.3151 |

| H(27)-C(7)-C(4) | 109.41 | 110.1897 | 0.7797 | 110.1323 | 0.7223 |

| H(26)-C(7)-C(8) | 109.41 | 108.1904 | 1.2196 | 109.269 | 0.141 |

| H(26)-C(7)-C(4) | 109.41 | 109.0971 | 0.3129 | 109.6308 | 0.2208 |

| C(8)-C(7)-C(4) | 109.5 | 112.8502 | 3.3502 | 112.1068 | 2.6068 |

| H(15)-C(5)-C(10) | 109.39 | 102.5448 | 6.8452 | 105.3454 | 4.0446 |

| H(15)-C(5)-C(4) | 109.39 | 104.681 | 4.709 | 107.3397 | 2.0503 |

| H(15)-C(5)-C(6) | 107.9 | 100.1873 | 7.7127 | 105.1387 | 2.7613 |

| C(10)-C(5)-C(4) | 109.51 | 113.024 | 3.514 | 110.8774 | 1.3674 |

| C(10)-C(5)-C(6) | 109.9 | 118.4479 | 8.5479 | 110.3225 | 0.4225 |

| C(4)-C(5)-C(6) | 109.9 | 115.0004 | 5.1004 | 116.9643 | 7.0643 |

| H(16)-C(4)-C(7) | 109.39 | 106.1747 | 3.2153 | 106.0092 | 3.3808 |

| H(16)-C(4)-C(3) | 109.39 | 105.2725 | 4.1175 | 105.8849 | 3.5051 |

| H(16)-C(4)-C(5) | 109.39 | 107.2835 | 2.1065 | 104.6194 | 4.7706 |

| C(7)-C(4)-C(3) | 109.51 | 111.0095 | 1.4995 | 110.4279 | 0.9179 |

| C(7)-C(4)-C(5) | 109.51 | 110.0741 | 0.5641 | 113.1926 | 3.6826 |

| C(3)-C(4)-C(5) | 109.51 | 116.3548 | 6.8448 | 115.7733 | 6.2633 |

| C(19)-C(17)-C(18) | 109.47 | 105.4049 | 4.0651 | 106.653 | 2.817 |

| C(19)-C(17)-C(11) | 109.47 | 112.6731 | 3.2031 | 113.7728 | 4.3028 |

| C(19)-C(17)-C(14) | 109.47 | 111.7611 | 2.2911 | 110.8882 | 1.4182 |

| C(18)-C(17)-C(11) | 109.47 | 114.8481 | 5.3781 | 112.873 | 3.403 |

| C(18)-C(17)-C(14) | 109.47 | 118.3062 | 8.8362 | 117.3857 | 7.9157 |

| C(11)-C(17)-C(14) | 109.47 | 93.9097 | 15.5603 | 95.2664 | 14.2036 |

| H(38)-C(13)-H(37) | 109.4 | 105.3497 | 4.0503 | 107.1526 | 2.2474 |

| H(38)-C(13)-C(14) | 109.41 | 108.9631 | 0.4469 | 109.0627 | 0.3473 |

| H(38)-C(13)-C(12) | 109.41 | 111.7753 | 2.3653 | 110.9946 | 1.5846 |

| H(37)-C(13)-C(14) | 109.41 | 116.5644 | 7.1544 | 114.962 | 5.552 |

| H(37)-C(13)-C(12) | 109.41 | 113.0048 | 3.5948 | 111.3039 | 1.8939 |

| C(14)-C(13)-C(12) | 109.5 | 101.2996 | 8.2004 | 103.3817 | 6.1183 |

| H(25)-C(3)-H(24) | 109.4 | 105.6002 | 3.7998 | 105.6928 | 3.7072 |

| H(25)-C(3)-C(2) | 109.41 | 108.3639 | 1.0461 | 109.6118 | 0.2018 |

| H(25)-C(3)-C(4) | 109.41 | 110.5209 | 1.1109 | 111.0167 | 1.6067 |

| H(24)-C(3)-C(2) | 109.41 | 112.0441 | 2.6341 | 111.602 | 2.192 |

| H(24)-C(3)-C(4) | 109.41 | 110.4205 | 1.0105 | 110.0368 | 0.6268 |

| C(2)-C(3)-C(4) | 109.5 | 109.8022 | 0.3022 | 108.8687 | 0.6313 |

| C(17)-C(14)-C(2) | 121.4 | 124.1308 | 2.7308 | 123.1395 | 1.7395 |

| C(17)-C(14)-C(13) | 117.2 | 107.5503 | 9.6497 | 108.2472 | 8.9528 |

| C(2)-C(14)-C(13) | 121.4 | 126.6323 | 5.2323 | 127.2626 | 5.8626 |

| H(23)-C(2)-C(14) | 120 | 119.2729 | 0.7271 | 119.5965 | 0.4035 |

| H(23)-C(2)-C(3) | 118.2 | 114.8523 | 3.3477 | 114.4542 | 3.7458 |

| C(14)-C(2)-C(3) | 122 | 124.7025 | 2.7025 | 124.1831 | 2.1831 |

The MMFF94 forcefield produces similar results. With atropisomer 6 having higher energy than atropisomer 7 and the chair conformation of the cyclohexane ring having lower energy than the twist-boat conformation. The equilibrium geometry predicted by the MMFF94 forcefield is similar to that predicted by MM2 forcefield.

Energies of the atropisomer 6 , 6' , 7 and 7' calculated with the MMFF94 forcefield

Atropisomer 6 Atropisomer 6' Atropisomer 7 Atropisomer 7' Total Energy: 70.5390 kcal/mol 76.2773 kcal/mol 60.5469 kcal/mol 66.3102 kcal/mol

The alkene in 6/6' and 7/7' are bridgehead alkenes, a violator of the celebrated "Bredt's Rule". Although bridgehead alkenes are highly strained and rare in small rings, they are permissible if the ring size is large. [5] In the seminal work by Maier and Schleyer, a parameter termed "olefinic strain" (OS) was used to quantify the difference in strain energy between the bridgehead olefin and the parent hydrocarbon using MM1 energies. [6] Rather fortuitously, some hydrocarbons were observed to have negative OS, i.e. it is less strained than the parent saturated hydrocarbon and the literature rationalised it in terms of "special stability afforded by the cage structure of the olefin". However, such conclusion is, to a large extent, unfounded as the MM1 forcefield does not parametrize bridgehead alkenes and hence extending MM2 energies to bridgehead alkenes is a large extrapolation.

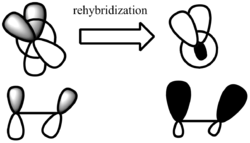

More importantly, the twisting of the π bond meant inferior p orbital overlap and significant weakening of the π bond. However,the loss of π bonding is partially recovered by rehybridization of the π centers, the consequence of which is pyramidalization with increased mixing of the 2s orbitals ([7]).

MM2 cannot take into account of rehybridisation unless a new "atom type" is defined. In fact, more recent study using composite G3/B3LYP method [8] reveals that the OS values in bridgehead alkene are much higher than that calculated previously, and some anti-Bredt species that were predicted to be stable by Maiser and Schleyer are in fact non minima on the potential energy surface. In fact, hyperstablility may be due to an increase in sp3 character which decrease the reactivity of the alkene.

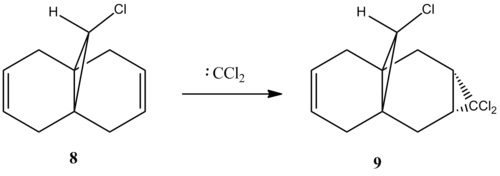

Regioselective Addition of Dichlorocarbene

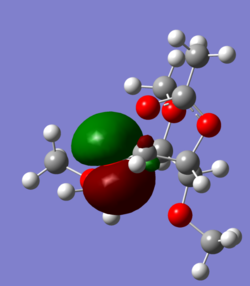

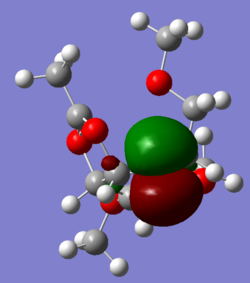

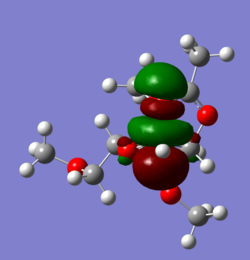

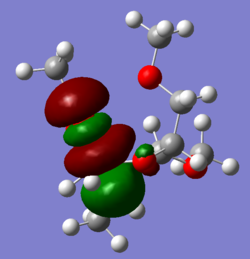

Dichlorocarbene were reported in the literature [9]to add, in a regioselective manner, to compound 8.

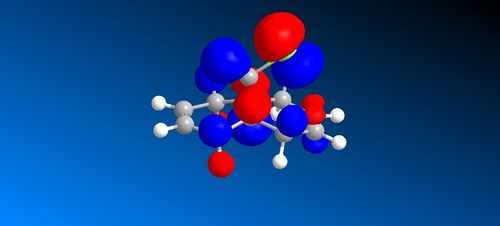

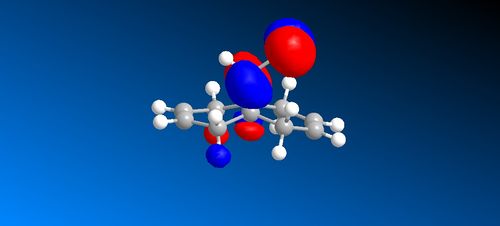

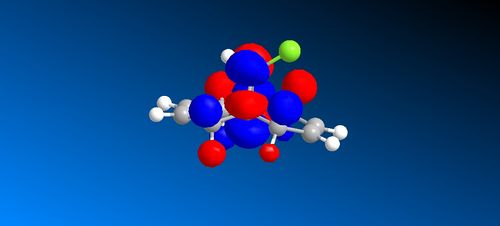

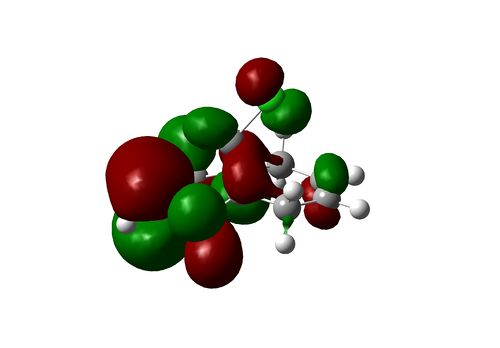

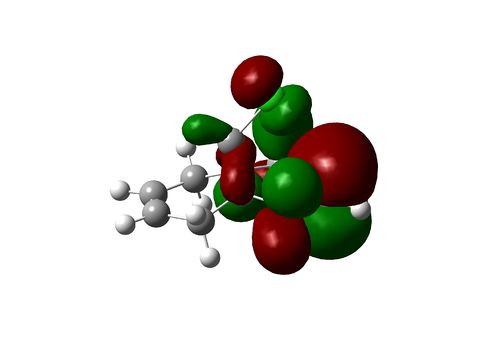

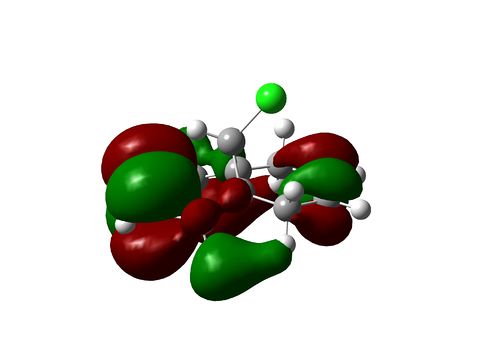

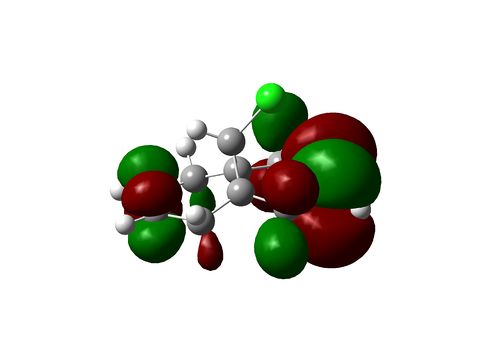

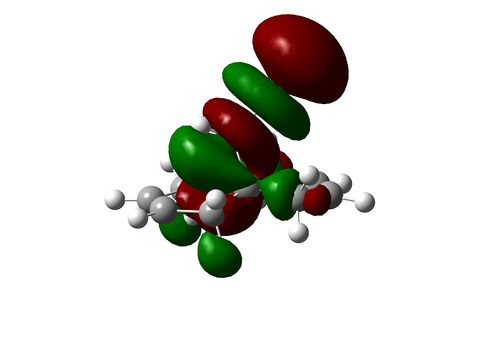

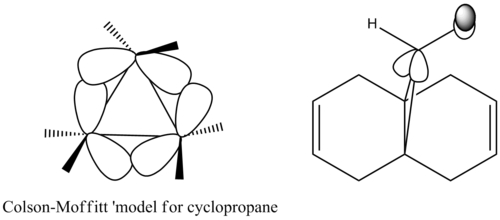

Molecular orbitals generated with semi-empirical method PM6 agreed with experimental observations. The molecular orbitals are symmetric, reflecting the existence of a plane of symmetry in the molecule.The HOMO of the compound is mainly located on the C-Cl bond, with rather curious pi like bonding. This may be rationalised by the Coulson-Moffitt picture of bonding in a highly strained system such as cyclopropane [10]. The ring strain forces the carbon atoms to rehybridise, incorporating more p character in the C-C bond. This enables the C-C bond to overlap effectively with the lone pair on chlorine. The rehybridisation also manifest itself in the short C-H bond 1.088 Å and short C-Cl bond of 1.760 Å as increased p character of the C-C bond are done at the expense of increased s character of the C-H and C-Cl bond on the cyclopropane ring.

Although the HOMO does not provide insight to the regioselectivity, the HOMO-1, which is less than 1eV higher than the HOMO, is located to a large extent on the olefin syn to the chloro substituent, rationalising why the electrophilic carbene react with the syn olefin.

In terms of reactivity with hypothetical nucleophilic reactants (although nucleophilic reaction with electron-rich alkene is rather unlikely), the LUMO of the system, which is very much separated in terms of energy from the HOMO, has a greater contribution from the olefin anti to the chloro substitutent. However, the LUMO+1, which is very close in energy to the LUMO, has greater contribution from the olefin syn to the chloro group and the LUMO+2 is significantly separated from the LUMO+1 in terms of energy to allow meaning influence on reactivity. Therefore, all in all, the system is expected to show poor regioselectivity for nucleophilic reaction.

In order to benchmark the accuracy of the PM6 calculation with a higher level of theory, the molecular orbitals of 8 is calculated using density functional theory, with hybrid functional B3LYP and basis set 6-31G(d,p). The results suggests that the PM6 orbitals were significantly erroneous. Most suprisingly, the HOMO is centred on the endo olefin and the HOMO-1 has contributions from both exo and endo olefin, with larger coefficient on the exo olefin. Visualisation of the HOMO-1 orbital suggests that it is the antiperiplanar overlap between σ*(C-Cl) and π*(C=C) (exo) that stablises the exo alkene and renders it less reactive.

In order to further investigate the effect of the chloro group on the vibrational frequencies of 8, the vibrational spectrum of the molecule is calculated using B3LYP/ 6-31G(d,p). The vibrational spectrum of hydro-8, where the exo alkene is hydrogenated, is also calculated.

| ν/cm-1 | Intensity | |

|---|---|---|

| C-Cl (major) | 770.85 | 25.1360 |

| C-Cl (minor) | 901.49 | 2.1591 |

| C-Cl (minor) | 930.06 | 7.2785 |

| C=C (exo) | 1737.15 | 4.2066 |

| C=C (endo) | 1757.37 | 3.9322 |

| C-H (cyclopropane) | 3197.07 | 2.5771 |

| ν/cm-1 | Intensity | |

|---|---|---|

| C-Cl (major) | 775.06 | 19.9819 |

| C-Cl (minor) | 908.19 | 4.2767 |

| C-Cl (minor) | 925.80 | 11.7891 |

| C-C (exo) | 1070.59 | 1.1757 |

| C=C (endo) | 1758.07 | 4.3405 |

| C-H (cyclopropane) | 3182.59 | 7.4734 |

The results correlates well with the MO analysis. In 8, some electron density from the exo alkene is donated into the σ*(C-Cl), therefore, the bond is weaker than the endo alkene and hence appear at lower frequency. Comparing 8 and hydro-8, the C-Cl bond in hydro-8 is stronger as the filling of the σ*(C-Cl) in '8 weakens the bond. There is no significant change in the C=C (endo) vibrational frequency as bond is largely unaffected by the C=C(exo).

In order to further investigate the effect of exo alkene on C-Cl stretch, a series of dienes will different substituents are modeled using B3LYP/6-31G(d,p).

| ν (C-Cl)/cm-1 | Intensity | C-Cl bond length / Å | |

|---|---|---|---|

| R=H | 770.85 | 25.1360 | 1.7890 |

| R=OMe | 765.14 | 9.3632 | 1.7887 |

| R=F | 766.95 | 7.9153 | 1.7869 |

| R=NO2 | 771.55 | 15.8722 | 1.7842 |

| R=SiH3 | 763.79 | 17.4848 | 1.7876 |

Electron donating substituents such as SiH3 and OMe enhances the electron density on the exo alkene and rises the energy of π(C=C), enabling better energy match with σ*(C-Cl) and thus stronger interaction. Donation into σ*(C-Cl) weakens the bond, thus the bond vibrate at a lower frequency due to lower force constant. Electron withdrawing substituents such as NO2 renders ν (C-Cl) higher than the unsubstituted alkene as the π(C=C) is now lower in energy and cannot overlap effectively with σ*(C-Cl). Interestingly, the fluro substituent, which is strongly electron withdrawing by inductive effect and electron donating by mesomeric effect actually puts ν (C-Cl) lower than the unsubstituted alkene, highlighting the dominance of resonance effect in this system. Curiously, the C-Cl bond length appears to be rather insensitive to change in substituent, which may be an artifact of the level of theory used.

| ν (endo C=C)/cm-1 | Intensity | ν (exo C=C)/cm-1 | Intensity | endo C=C bond length / Å | exo C=C bond length / Å | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R=H | 1757.37 | 3.9322 | 1737.15 | 4.2066 | 1.3318 | 1.3355 |

| R=OMe | 1756.34 | 8.6348 | 1736.55 | 74.7221 | 1.3320 | 1.3415 |

| R=F | 1756.09 | 4.3040 | 1779.50 | 46.0208 | 1.3319 | 1.3295 |

| R=NO2 | 1758.06 | 3.1792 | 1738.89 | 46.0208 | 1.3316 | 1.3358 |

| R=SiH3 | 1756.21 | 5.4926 | 1690.28 | 19.0335 | 1.3321 | 1.3449 |

The exo C=C stretch mirrors the trend observed in C-Cl stretch. Electron donating substituents allows the exo alkene to better overlap with σ*(C-Cl), taking away electron density from the C=C bond thus weakening it. Although electron withdrawing substituents such as NO2 diminishes electron density on the alkene by resonance, in this case it is the lost in π(C=C)->σ*(C-Cl) that dominates and hence NO2 puts ν (exo C=C) slightly higher than the unsubstituted alkene. The fluro substituent is an anomaly in trend and can be rationalised by the the fluro group being a resonance electron donor whilst inductively withdrawing electron density.

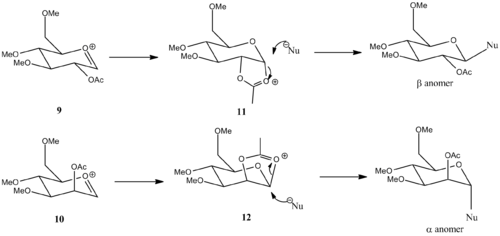

Neighboring Group Participation in Koenigs-Knorr Glycosidation

Glycosidation involves replacing the anomeric group X by reaction with a nucleophile Nu. The pioneering work by Winstein [11] showed that groups near the reaction center can influence the stereochemical outcome of a displacement reaction. In the case of glycosidation, the stereochemical outcome of glycosidation depends on the orientation of the OAc group on the adjacent carbon. That is because of the acetate group trapping the planar oxonium ion intermediate, forming the acetoxonium ion thus directing which face must the nucleophile attack.

In order to investigate the participation of the acetate group, MM2 and PM6 methods were used to obtain the geometry of the oxonium ion 9/10 and the trapped species 11/12. 9 and 9 are conformers with 9' having the acetate group equatorial and 9 has acetate group occupying axial position. Similar relationship for 10 and 10'. Visualisation of the structure reveals that the acetate group cannot reach to interact with the oxinium ion in the equitorial conformers. This is also reflected in the energies - the charge-dipole interaction between the carbonyl dipole and positive charge strongly favours the axial conformer.

| 9 | 9' | 10 | 10' | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 2.6 | 2.362 | 2.5317 | 2.3865 |

| Bend | 12.0757 | 11.4134 | 10.1867 | 11.3019 |

| Stretch-Bend | 0.9959 | 0.9401 | 0.9113 | 0.8462 |

| Torsion | 1.5048 | 0.625 | 1.5527 | 0.9639 |

| Non-1,4 VdW | 1.6731 | -2.2443 | -0.3408 | -1.0219 |

| 1,4 VdW | 18.8436 | 18.0329 | 18.9722 | 18.9312 |

| Charge-Dipole | -31.5347 | -0.2716 | -20.4724 | -14.7659 |

| Dipole-Dipole | 9.0583 | 5.6628 | 4.9308 | 6.4839 |

| Total Energy/kcal mol-1 | 15.2168 | 36.5203 | 18.2723 | 25.1257 |

The same trend in total energy is confirmed by PM6 calculations.

| 9 | 9' | 10 | 10' | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heat of formation/kcal mol-1 | -91.66347 | -77.66580 | -88.73090 | -74.79485 |

However, examining the orientation of the carbonyl group with respect to the oxinium ion reveals that PM6 method sucessfully predicts the Burgi-Dunitz angle for conformer 9 and 10. The angles that MM2 predict are too acute. This is because the Burgi-Dunitz angle is a stereoelectric effect that has origins in effective orbital overlap between π*(C=O+) and lone pair on O. Orbital overlap is not included in classical forcefields thus the MM2 method fails to predict the reactive conformations.

| 9 | 9' | 10 | 10' | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MM2 | 82.9o | 165.9o | 95.1o | 158.2o |

| PM6 | 104.7 | 147.5o | 105.8o | 152.4o |

Endo Product |

PM6 Optimised geometry of 9

Endo Product |

PM6 Optimised geometry of 10

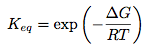

Using the PM6 energies, and the formula

with ΔG being the difference in energy between the 2 conformers, the equilibrium constant Keq,1=[9]/[9']=1.58x1010 and Keq,2=[10]/[10']=1.41x1010. Hence 9/10 will be the dominant species in solution.

The equilibrium structure of bicyclic intermediate 11, 11' , 12 and 12' is also obtained using MM2 and PM6. The primed species have trans ring junction whereas the unprimed species have cis ring junction.

| 11 | 11' | 12 | 12' | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bend | 16.0834 | 17.467 | 20.4667 | 21.093 |

| Stretch-Bend | 0.6975 | 0.7956 | 0.7448 | 0.7925 |

| Torsion | 7.7753 | 8.1656 | 8.6719 | 6.2487 |

| Non-1,4 VdW | -4.0437 | -2.4349 | -2.3049 | -2.9914 |

| 1,4 VdW | 17.6964 | 19.3975 | 17.6245 | 18.7346 |

| Dipole-Dipole | -0.4036 | -1.745 | 0.9993 | -1.0212 |

| Total Energy/ kcal mol-1 | 34.5318 | 44.0259 | 27.6149 | 41.979 |

The PM6 energies mirrors the trend of the MM2 energy, with cis ring junction being more stable than trans ring junction.

| 11 | 11' | 12 | 12'' | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heat of formation/kcal mol-1 | -91.6637 | -66.883 | -90.5127 | -66.2174 |

However, the eqilibrium geometry predicted by PM6 has the six membered ring in almost twist-boat conformation whilst the MM2 predicts a almost chair conformation. This result does not depend on whether the starting geometry is chair-like or twist-boat-like. This is likely due to the anomeric effect which is taken into account by PM6, which offsets the torsional strain in the twist-boat conformation. The chair conformation does not allow good overlap between the oxygen lone pair and σ*(C-O+).

Endo Product |

PM6 Optimised geometry of 11

Endo Product |

PM6 Optimised geometry of 12

| 11 | 11' | 12 | 12' | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MM2 | 107.2o | 122.5o | 119.8o | 124.0o |

| PM6 | 104.8 | 112.0o | 106.2o | 113.5o |

Further geometry optimisation at DFT B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level agrees with angles produces using PM6. Analysis with Natural Bonding Orbital reveals a fully formed C-O bond with particularly strong anomeric n(O)->σ*(C-O+) interaction.

| 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|

| n(O)->σ*(C-O+) stabilisation energy kcal/mol | 35.90 | 43.29 |

Using the PM6 method, the stabilisation energy from 9->11 and 10->12 is 0.23 cal/mol=0.96 J/mol and 1.78 kcal/mol=7.5 kJ/mol respectively. In both cases, there is a thermodynamic driving force for conformer 9/10 to prevail, and a thermodynamic driving force for the "correct" conformer to form cis ring junction intermediate. This explains the diastereoselectvity of the reaction as the cis ring junction forces the incoming nucleophile to approach the opposite side of the ring.

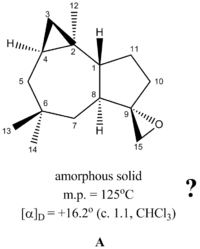

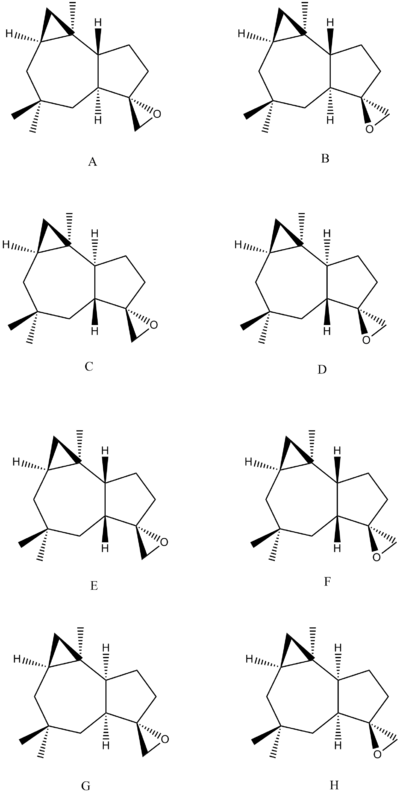

Miniproject: The Mystery of Epoxyafricane

The africanenes is a family of sesquiterpenoids featuring a fused tricyclic system of cycloprpane, cyclopentane and cycloheptane. The africanenes are isolated in various different natural products, including the plant Lippa intergrifolia, [12] which grows in the tropical and subtropical regions of South America, Central America and Africa, and soft corals Sinularia erecta and Sinularia polydactila. [13] In 1999, the Venkateswarlu group reported the isolation of epoxyafricane (A), a oxygenated sesquiterpene, from the soft coral Sinularia dissecta Tixier Durivalt (Alcyoniidae) collected from the Mandapam coast of India. [14]

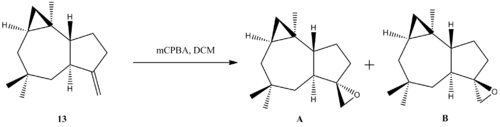

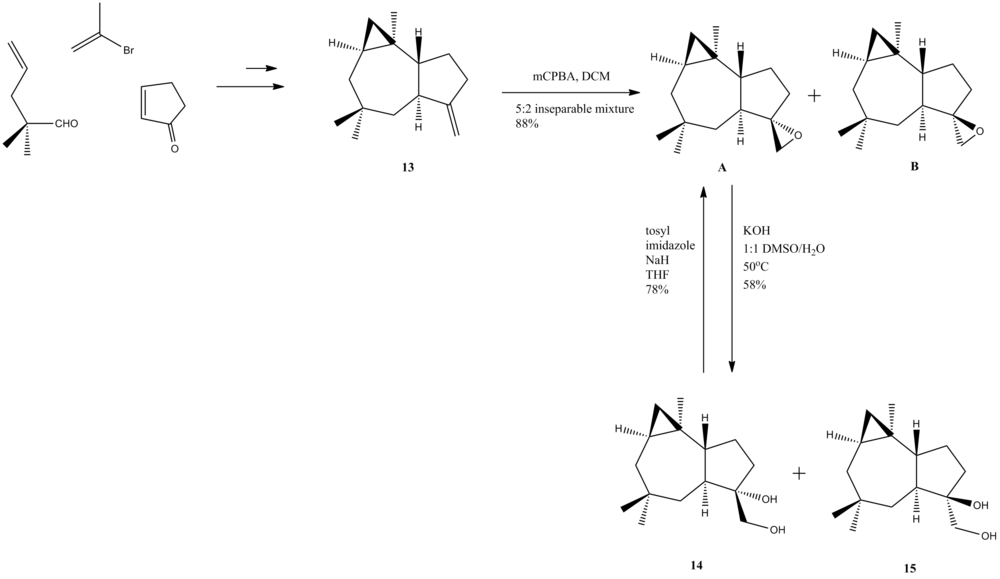

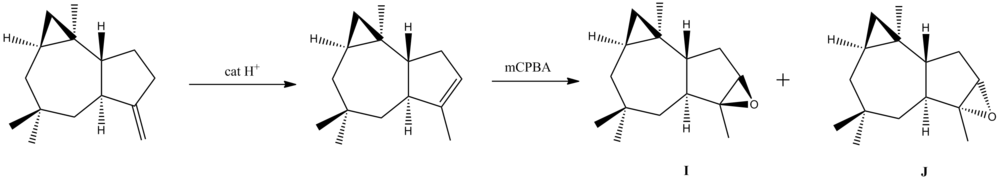

The Venkatesvarlu group assigned the structure of A based on 1H, 13C, COSY and NOESY NMR. The resonances at 3.57 (1H,d, J=13.5 Hz, H-15) and 3.46 (1H,d, J=13.5 Hz, H-15) in 1H NMR, in conjunction with the resonance at 82.9 and 68.9 in 13C NMR with DEPT revealing the former as a tertiary centre and the latter as a secondary centre was used as a basis for assigning the epoxy group (see detail spectral listing below). The Venkatesvarlu group also did synthetic studies to confirm the epoxide structure, and it was reported that epoxidation of the alkene Δ9(15)-Africanene (13) yields an inseparable mixture of A and its C9 epimer as confirmed by NMR.

In 2011, the Nakata group reported a total synthesis of Δ9(15)-Africanene (13), utilising ring closing metathesis as the key synthetic step to build the seven membered ring. [15] Epoxidation of Δ9(15)-Africanene (13) with mCPBA yield a diastereomeric mixture of epoxides, which is separated by further reaction with base, which generates a separable mixture of diols. The diols crystallised and characterised by X-ray crystallography. The epoxide is then reformed by reaction with tosyl imidazole, transforming the primary hydroxyl to a leaving group, followed by sodium hydride as base to deprotonate the tertiary hydroxyl. Interestingly, the NMR of the epoxide, which is a colourless syrup, is not congruent with the NMR data reported by Venkateswarlu group. It seems that under identical reaction condition (epoxidation of Δ9(15)-Africanene with mCPBA), the two groups obtained divergent results! Even more interestingly, both groups did a OsO4 dihydroxylation on 13 to confirm the structure of 13, and the spectral data for the resulting diol obtained from both groups are in agreement with each other.

Endo Product |

Reported crystal structure of 14 by the Nakata group

This miniproject aims to shed some light on the apparent mystery by establishing, using GIAO NMR prediction, whether the Nakata group obtained epoxide A as they claimed, and if so, what is the natural product that the Venkatesvarlu group isolated.

Confirmation of the Structure of Epoxyafricane

In order to confirm the structure of epoxyafricane, GIAO NMR prediction is used to compare the 13C NMR data obtained by the Venkateswarlu group and the Nakata group. Following the celebrated structural reassignment of Obtusallenes [16] and Hexacyclinol [17] via GIAO NMR prediction, density funational theory using mPW1PW91 as exchange correlational functional and 6-31G(d,p) as basis set is used. The literature has reported various different basis set and exchange-correlation functionals for NMR prediction, such as M06/pc-2 used in Vannusal B [18] and mPW1PW91/6-311þG(2d,p) used in structural reassignment of Nobilisitine A [19]. In both examples, DFT GIAO prediction of 13C NMR can be used to distinguish between diastereoisomers, as opposed to constitutional isomers in the case of Hexacylinol and Obtuallenes. Balancing between efficiency and accuracy, the protocol used in the structural reassignment of Obtusallenes is used in this project. Stable conformers are identified using the MM2 forcefield and optimised using PM6. 2 conformations for the seven membered ring (chair-like and boat-like [20] ), and 2 envelop conformations for the five membered ring are explored (in total 4 conformations) are explored. However in the majority of cases not all conformations are stable enough to resist optimisation by PM6. The PM6 optimised structures are then optomised using mPW1PW91/6-31G(d,p) with solvent effect modelled using polarisable continuum model CPCM, followed by GIAO NMR prediction using the same basis set and exchange correlation functional.

Methods to quantify the extent to which the calculated spectra matches the experimental data are still hotly debated in the literature. Common methods range from relatively simple metrics such as maximum deviation, average deviation and linear goodness-of-fit regression coefficient. Recently, the Goodman group has pioneered more sophisticated probabilistic models for comparing predicted and experimental NMR. The CP3 method [21] is optimised to tell, given 2 predicted and 2 measured spectra, which calculated spectrum is most likely to correspond to each experimental spectrum and gives a measure of its confidence in its conclusion. The DP4 method, [22] on the other hand, is optimised to assign the experimental spectra to the most likely candidate structure given the predicted NMR spectra for the candidate structures.

| Nakata Group Data | Venkateswarlu Group Data | |

|---|---|---|

| C9 | 68.5 | 82.9 |

| C1 | 52.4 | 68.9 |

| C15 | 50.3 | 49.8 |

| C7 | 47.5 | 44.4 |

| C5 | 43.1 | 44.4 |

| C8 | 41 | 43.2 |

| C10 | 33.92 | 37.3 |

| C13 | 33.9 | 33.9 |

| C6 | 33.4 | 33.3 |

| C11 | 26 | 29.6 |

| C14 | 23.9 | 24.2 |

| C3 | 23.3 | 23.6 |

| C4 | 21.9 | 21.8 |

| C12 | 20.2 | 19.7 |

| C2 | 19.2 | 19.7 |

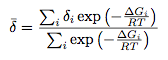

Extensive conformational search revealed 3 stable conformers for A. The energies of the structures, calculated using DFT at the mpw1pw91/6-31g(d,p) level was used to calculate Boltzmann weight for each conformer. The chemical shifts are than Boltzmann averaged to obtain an average chemical shift for A.

where i denotes the different conformers, ΔG is the difference in energy between the conformer i and the lowest energy conformer and δi is the chemical shifts calculated for conformer i.

| A | A' | A'' | Boltzmann-averaged chemical shift | Deviation from Nakata data | Deviation from Venkateswarlu data | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (Hatree) | -661.104 | -661.119 | -661.103 | |||

| Boltzmann weight | 2.74E-07 | 1.00E+00 | 7.75E-08 | |||

| C9 | 64.20 | 67.41 | 67.86 | 67.41 | -1.09 | -15.49 |

| C15 | 51.34 | 48.52 | 47.55 | 48.52 | -1.78 | -1.28 |

| C1 | 47.94 | 53.75 | 48.57 | 53.75 | 1.35 | -15.15 |

| C8 | 42.62 | 43.23 | 46.66 | 43.23 | 2.23 | 0.03 |

| C5 | 37.39 | 42.99 | 38.84 | 42.99 | -0.11 | -1.41 |

| C7 | 35.42 | 48.08 | 43.65 | 48.08 | 0.58 | 3.68 |

| C14 | 33.47 | 24.51 | 37.68 | 24.51 | 0.61 | 0.31 |

| C6 | 32.55 | 34.29 | 32.52 | 34.29 | 0.89 | 0.99 |

| C13 | 30.24 | 34.10 | 32.08 | 34.10 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| C11 | 29.46 | 29.15 | 30.66 | 29.15 | 3.15 | -0.45 |

| C10 | 29.06 | 36.39 | 35.58 | 36.39 | 2.47 | -0.91 |

| C4 | 27.60 | 23.39 | 26.34 | 23.39 | 1.49 | 1.59 |

| C12 | 26.42 | 21.48 | 24.77 | 21.48 | 1.28 | 1.78 |

| C3 | 20.33 | 24.45 | 21.27 | 24.45 | 0.85 | 0.85 |

| C2 | 19.76 | 21.99 | 23.67 | 21.99 | 2.79 | 2.29 |

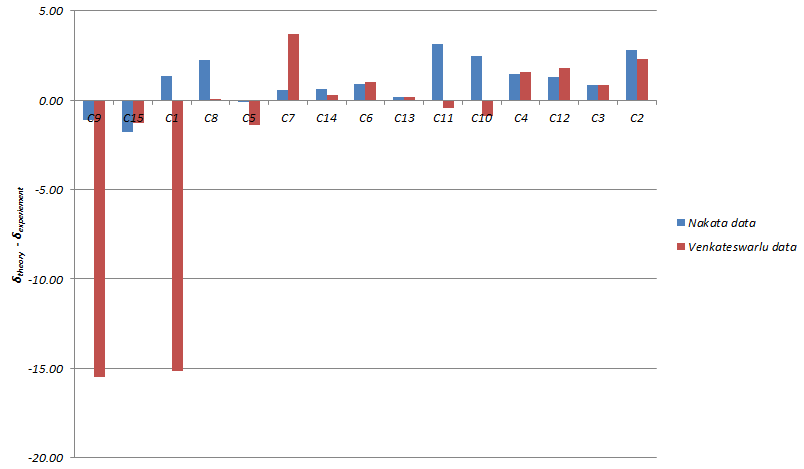

The Venkateswarlu data deviates significantly from predicted NMR shift in C9 and C1. Plotting out the deviation for different carbon atoms showed clearly that the predicted NMR matches data from the Nakata group (maximum deviation=3.15ppm) more than that of the Venkateswarlu group (maximum deviation=15.49ppm).

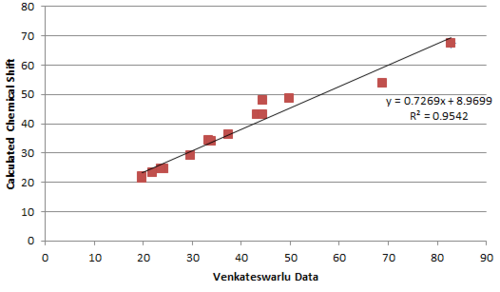

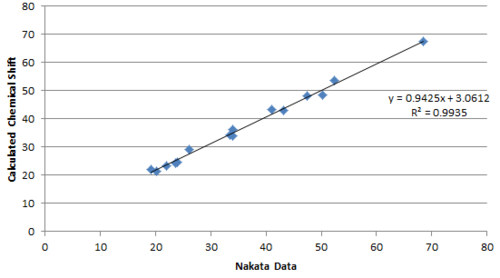

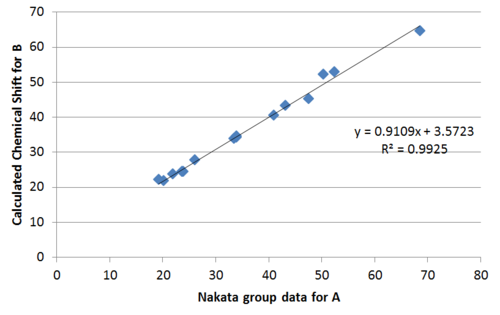

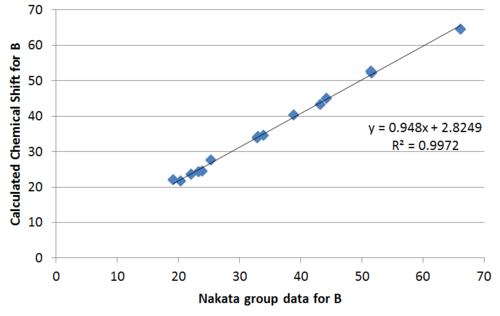

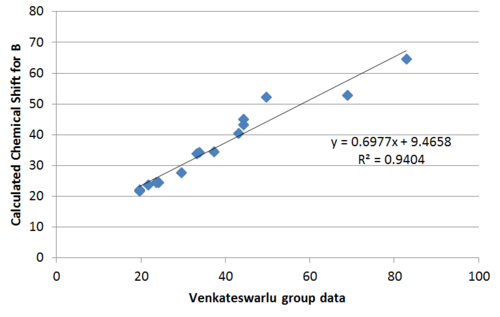

Plotting the calculated chemical shift againest experimental chemical shift reveals clearly a much better match by the Nakata group data compared to Venkateswarlu in terms of the R2 value.

All in all, it is clear that the Nakata group matches calculated NMR data to a much larger extent compared to the Venkateswarlu group. However, another question to answer is whether the Nakata group has assigned the correct stereochemistry at the C9 position, and whether the Venkatewaru group has in fact isolated the C9 epimer. In order to address this, GIAO NMR prediction of B was done. Extensive conformation search reveals 4 stable conformers, and the Boltzmann-averaged chemical shift is compared with the experimental data of Nakata group and Venkatewaru group. Fortunately, the Nakata group has also provided NMR data for B.

| B | B' | B'' | B''' | Boltzmann averaged chemical shift | Deviation from Nakata Group Data for A | Deviation from Nakata Group Data for B | Deviation from Venkateswarlu Group Data | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (Hatree) | -661.105 | -661.119 | -661.118 | -661.103 | ||||

| Boltzmann Weight | 3.08E-07 | 8.77E-01 | 1.23E-01 | 2.80E-08 | ||||

| C9 | 63.53 | 64.23 | 66.89 | 65.23 | 64.55 | -3.95 | -1.55 | -18.35 |

| C15 | 47.02 | 53.08 | 45.37 | 55.31 | 52.13 | 1.83 | 0.53 | 2.33 |

| C1 | 50.67 | 53.08 | 50.23 | 48.28 | 52.73 | 0.33 | 1.21 | -16.17 |

| C8 | 43.58 | 40.25 | 41.18 | 43.10 | 40.36 | -0.64 | 1.46 | -2.84 |

| C5 | 37.66 | 43.28 | 43.16 | 38.76 | 43.26 | 0.16 | 0.06 | -1.14 |

| C7 | 35.79 | 45.45 | 42.26 | 41.56 | 45.06 | -2.44 | 0.86 | 0.66 |

| C14 | 33.25 | 24.34 | 24.95 | 37.68 | 24.41 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.21 |

| C6 | 32.00 | 33.83 | 33.85 | 32.04 | 33.84 | 0.44 | 0.94 | 0.54 |

| C13 | 31.87 | 34.16 | 34.09 | 32.20 | 34.15 | 0.25 | 1.15 | 0.25 |

| C11 | 30.74 | 28.02 | 24.95 | 28.93 | 27.64 | 1.64 | 2.34 | -1.96 |

| C10 | 30.31 | 34.44 | 34.90 | 33.98 | 34.50 | 0.58 | 0.60 | -2.80 |

| C4 | 27.91 | 23.67 | 23.24 | 26.40 | 23.61 | 1.71 | 1.51 | 1.81 |

| C12 | 26.99 | 21.84 | 20.25 | 25.09 | 21.65 | 1.45 | 1.25 | 1.95 |

| C3 | 20.54 | 24.34 | 24.65 | 21.37 | 24.38 | 0.78 | 1.08 | 0.78 |

| C2 | 19.70 | 21.84 | 23.93 | 23.54 | 22.10 | 2.90 | 2.90 | 2.40 |

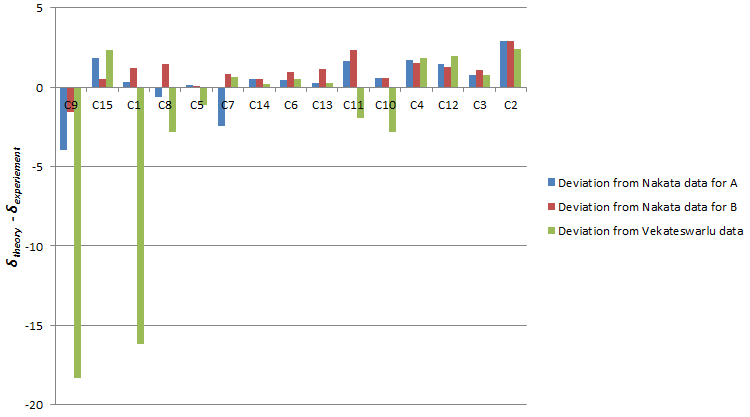

Graphical inspection of the deviation from calculated chemical shift showed that the Venkatewaru group data is significantly different from calculated chemical shifts.

Performing regression analysis, the Venkatewaru group data gave a relatively poor R2 value compared to the Nakata group data. Comparing between Nakata group data reported for A and B, it is also clear from R2 value that the calculated chemical shift matches the reported data of B to a greater extent that A.

Using the CP3 probabilistic model, [21] with the experimental data for Nakata group and calculated chemical shift entered into the algorithm, returns the result that with 100% confidence CP3 assigns the predicted spectra of A to experimental data for A and predicted spectra for B to experimental data for B, confirming the assignment of the C9 epimeric center by the Nakata group.

| Maximum Deviation | Average Deviation | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calculated chemical shift for A-Venkatewaru group data | 15.49 | 3.09 | 0.9542 |

| Calculated chemical shift for A-Nakata group data for A | 3.15 | 1.39 | 0.9935 |

| Calculated chemical shift for A-Nakata group data for B | 4.33 | 2.05 | 0.9824 |

| Calculated chemical shift for B-Venkatewaru group data | 18.35 | 3.61 | 0.9404 |

| Calculated chemical shift for B-Nakata group data for A | 3.15 | 1.31 | 0.9925 |

| Calculated chemical shift for B-Nakata group data for B | 2.90 | 1.20 | 0.9972 |

All in all, from GIAO NMR prediction of 13C chemical shift, it can be concluded that the Nakata group has synthesized the nominal epoxyafricane whilst the NMR data provided by the Venkatewaru group suggests that the isolated natural product is not epoxyafricane. Interestingly, although only using mPW1PW91/6-31G(d,p) level of theory, the agreement with experimental data are comparable with that obtained using higher level of theory. [18]

What has the Venkateswarlu group isolated?

Curiously, although epoxidation of Δ9(15)-Africanene (13) is reported in the paper by the Venkateswarlu group, no NMR shifts for the synthetic epoxide is reported, and according to the experimental section, no attempt has been made to purify the crude product, let alone resolving the C9 epimeric mixture. As such, it is plausible that similarity in the spectrum of the synthetic epoxide (A) to the isolated epoxide (A) is an artifact of contaminated spectrum. The lack of characteristic OH stretch in the IR peaks listed in the experimental ruled out the existence of hydroxy group, and the elemental analysis and EIMS data agreed with the chemical formula. As such, as a first guess, 13C NMR for all diastereoisomers of (A) are calculated to and compared with the Venkateswarlu data.

Diastereoisomer C

| C | C' | Boltzmann Averaged Chemical Shift | Deviation from Venkateswarlu Data | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy/hatree | -661.11 | -661.11 | ||

| Boltzmann Weight | 0.46 | 0.54 | ||

| C9 | 63.91 | 64.65 | 64.31 | -18.59 |

| C15 | 49.30 | 51.36 | 50.42 | 0.62 |

| C1 | 50.78 | 49.21 | 49.93 | -18.97 |

| C8 | 41.60 | 40.33 | 40.91 | -2.29 |

| C5 | 39.33 | 39.83 | 39.60 | -4.80 |

| C7 | 41.96 | 40.55 | 41.19 | -3.21 |

| C14 | 36.67 | 29.43 | 32.75 | 8.55 |

| C6 | 33.55 | 32.25 | 32.84 | -0.46 |

| C13 | 26.32 | 34.30 | 30.64 | -3.26 |

| C11 | 31.05 | 31.31 | 31.19 | 1.59 |

| C10 | 32.68 | 32.84 | 32.76 | -4.54 |

| C4 | 27.46 | 25.01 | 26.13 | 4.33 |

| C12 | 27.83 | 27.97 | 27.90 | 8.20 |

| C3 | 12.79 | 17.41 | 15.30 | -8.30 |

| C2 | 24.07 | 24.40 | 24.25 | 4.55 |

Diastereoisomer D

| D | D' | Boltzmann Averaged Chemical Shift | Deviation from Venkateswarlu Data | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (hatree) | -661.097 | -661.112 | ||

| Boltzmann Weight | 1.32E-07 | 1.00 | ||

| C8 | 73.13 | 67.27 | 67.27 | -15.63 |

| C15 | 56.19 | 49.89 | 49.89 | 0.09 |

| C6 | 54.01 | 49.57 | 49.57 | -19.33 |

| C5 | 47.25 | 41.79 | 41.79 | -1.41 |

| C2 | 39.95 | 39.47 | 39.47 | -4.93 |

| C4 | 49.50 | 43.50 | 43.50 | -0.90 |

| C11 | 35.42 | 29.16 | 29.16 | 4.96 |

| C3 | 36.39 | 32.65 | 32.65 | -0.65 |

| C12 | 26.66 | 34.22 | 34.22 | 0.32 |

| C10 | 32.35 | 31.54 | 31.54 | 1.94 |

| C9 | 35.28 | 34.04 | 34.04 | -3.26 |

| C1 | 29.24 | 24.89 | 24.89 | 3.09 |

| C14 | 25.72 | 28.07 | 28.07 | 8.37 |

| C13 | 19.18 | 17.37 | 17.37 | -6.23 |

| C7 | 26.35 | 24.55 | 24.55 | 4.85 |

Diastereoisomer E

| E | E' | Boltzmann Averaged Chemical Shift | Deviation from Venkateswarlu Data | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy/hatree | -661.1077752 | -661.1144718 | ||

| Boltzmann Weight | 8.68E-04 | 9.99E-01 | ||

| C9 | 67.30 | 66.05 | 66.06 | -16.84 |

| C15 | 57.06 | 46.36 | 46.37 | -3.43 |

| C1 | 48.09 | 46.42 | 46.42 | -22.48 |

| C8 | 43.29 | 40.35 | 40.35 | -2.85 |

| C5 | 39.81 | 40.88 | 40.88 | -3.52 |

| C7 | 39.44 | 35.29 | 35.29 | -9.11 |

| C14 | 37.10 | 29.83 | 29.84 | 5.64 |

| C6 | 34.53 | 33.96 | 33.96 | 0.66 |

| C13 | 26.19 | 28.82 | 28.81 | -5.09 |

| C11 | 28.06 | 26.90 | 26.91 | -2.69 |

| C10 | 29.09 | 34.94 | 34.94 | -2.36 |

| C4 | 27.42 | 23.48 | 23.48 | 1.68 |

| C12 | 27.76 | 23.82 | 23.82 | 4.12 |

| C3 | 17.67 | 22.04 | 22.04 | -1.56 |

| C2 | 23.70 | 20.08 | 20.08 | 0.38 |

Diastereoisomer F

| F | F' | Boltzmann Averaged Chemical Shift | Deviation from Venkateswarlu Data | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy/hatree | -661.1080863 | -661.1087571 | ||

| Boltzmann weight | 0.33 | 0.67 | ||

| C9 | 69.80 | 68.91 | 69.21 | -13.69 |

| C15 | 48.66 | 52.29 | 51.09 | 1.29 |

| C1 | 49.41 | 47.94 | 48.42 | -20.48 |

| C8 | 46.17 | 44.19 | 44.84 | 1.64 |

| C5 | 39.70 | 41.84 | 41.13 | -3.27 |

| C7 | 41.33 | 41.33 | 41.33 | -3.07 |

| C14 | 37.17 | 28.93 | 31.65 | 7.45 |

| C6 | 34.75 | 34.58 | 34.64 | 1.34 |

| C13 | 26.29 | 29.14 | 28.20 | -5.70 |

| C11 | 28.36 | 31.44 | 30.42 | 0.82 |

| C10 | 31.07 | 32.46 | 32.00 | -5.30 |

| C4 | 27.32 | 25.13 | 25.85 | 4.05 |

| C12 | 28.20 | 27.47 | 27.71 | 8.01 |

| C3 | 17.78 | 26.84 | 23.85 | 0.25 |

| C2 | 23.69 | 19.33 | 20.77 | 1.07 |

Diastereoisomer G

| G | G' | Boltzmann Averaged Chemical Shift | Deviation from Venkateswarlu Data | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (Hatree) | -661.1071413 | -661.1109983 | ||

| Boltzmann weight | 0.02 | 1.00 | ||

| C9 | 69.85 | 68.68 | 69.86 | -13.04 |

| C15 | 48.44 | 48.66 | 49.48 | -0.32 |

| C1 | 45.63 | 49.23 | 50.00 | -18.90 |

| C8 | 45.33 | 45.27 | 46.04 | 2.84 |

| C5 | 35.76 | 43.68 | 44.29 | -0.11 |

| C7 | 36.40 | 43.76 | 44.38 | -0.02 |

| C14 | 32.83 | 23.95 | 24.51 | 0.31 |

| C6 | 33.12 | 34.88 | 35.44 | 2.14 |

| C13 | 30.03 | 34.44 | 34.95 | 1.05 |

| C11 | 30.22 | 29.14 | 29.65 | 0.05 |

| C10 | 30.11 | 30.79 | 31.30 | -6.00 |

| C4 | 27.02 | 23.95 | 24.41 | 2.61 |

| C12 | 29.48 | 30.18 | 30.68 | 10.98 |

| C3 | 17.35 | 21.87 | 22.16 | -1.44 |

| C2 | 23.49 | 20.86 | 21.26 | 1.56 |

Diastereoisomer H

| H | H' | Boltzmann Averaged Chemical Shift | Deviation from Venkateswarlu Data | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy/ hatree | -661.1069868 | -661.1104422 | ||

| Boltzmann weight | 0.03 | 0.97 | ||

| C9 | 65.76 | 66.85 | 66.82 | -16.08 |

| C15 | 55.41 | 56.26 | 56.23 | 6.43 |

| C1 | 45.94 | 47.93 | 47.88 | -21.02 |

| C8 | 41.50 | 42.56 | 42.53 | -0.67 |

| C5 | 35.95 | 44.03 | 43.83 | -0.57 |

| C7 | 33.67 | 42.46 | 42.24 | -2.16 |

| C14 | 32.79 | 23.78 | 24.01 | -0.19 |

| C6 | 32.60 | 34.73 | 34.67 | 1.37 |

| C13 | 30.18 | 34.44 | 34.33 | 0.43 |

| C11 | 30.27 | 28.61 | 28.65 | -0.95 |

| C10 | 31.18 | 29.01 | 29.07 | -8.23 |

| C4 | 26.29 | 23.98 | 24.04 | 2.24 |

| C12 | 29.57 | 30.23 | 30.22 | 10.52 |

| C3 | 16.99 | 21.50 | 21.39 | -2.21 |

| C2 | 22.70 | 21.17 | 21.21 | 1.51 |

As seen from the tables, it is evident that the large deviation from predicted chemical shift that none of the 8 diastereoisomers match the data from the Venkateswarlu group. Comparing the procedures from mCPBA epoxidation reported by the Venkateswarlu group and Nakata group, the Venkateswarlu group had the reaction mixture stirred at 0oC for 6h whereas the Nakata group had the reaction mixture stirred at room temperature for 1h. Both groups added 2 equivalent of mCPBA. As the Venkateswarlu group involves longer reaction time, it is likely that the olefin may isomerise. Isomerisation of Δ9(15)-Africanene upon exposure to acid is in fact reported in the literature, and it is plausible that the mCPBA reagent used in the Venkateswarlu group contain large amount of meta-chlorobenzoic acid. [23]

Therefore, the 13C NMR chemical shifts for I and J are calculated to see whether the high chemical shifts at 82.9 ppm and 68.9 ppm in the Venkateswarlu group data, corresponding to the epoxide, are predicted.

Isomer I

| I | I' | Boltzmann averaged chemical shift | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (Hatree) | -661.131 | -661.114 | |

| Boltzmann weight | 2.07e-08 | 1.00 | |

| C9 | 65.57 | 66.36 | 66.36 |

| C15 | 17.39 | 17.36 | 17.36 |

| C1 | 47.62 | 43.14 | 43.14 |

| C8 | 42.42 | 45.28 | 45.28 |

| C5 | 42.98 | 39.12 | 39.12 |

| C7 | 44.12 | 39.92 | 39.92 |

| C14 | 24.87 | 37.75 | 37.75 |

| C6 | 33.90 | 32.14 | 32.14 |

| C13 | 34.19 | 31.76 | 31.76 |

| C11 | 30.26 | 32.24 | 32.24 |

| C10 | 62.28 | 63.71 | 63.71 |

| C4 | 23.70 | 26.44 | 26.44 |

| C12 | 22.06 | 26.23 | 26.23 |

| C3 | 24.42 | 21.19 | 21.19 |

| C2 | 21.02 | 23.05 | 23.05 |

Isomer J

| J | J' | Boltzmann averaged chemical shift | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (Hatree) | -661.107 | -661.125 | |

| Boltzmann weight | 7.44E-09 | 1.00E+00 | |

| C8 | 69.12 | 69.10 | 69.10 |

| C15 | 18.50 | 17.86 | 17.86 |

| C6 | 59.87 | 58.41 | 58.41 |

| C5 | 44.68 | 44.66 | 44.66 |

| C2 | 37.45 | 43.09 | 43.09 |

| C4 | 39.35 | 47.02 | 47.02 |

| C11 | 33.70 | 24.60 | 24.60 |

| C3 | 32.51 | 34.65 | 34.65 |

| C12 | 30.36 | 34.17 | 34.17 |

| C10 | 33.55 | 30.02 | 30.02 |

| C9 | 64.03 | 66.70 | 66.70 |

| C1 | 27.92 | 23.36 | 23.36 |

| C14 | 26.82 | 20.99 | 20.99 |

| C13 | 21.41 | 24.07 | 24.07 |

| C7 | 19.02 | 22.48 | 22.48 |

From inspection of the predicted chemical shifts, it is evident that none of Isomers I and J match the experimental data from the Venkateswarlu group, especially the high chemical shifts at 82.9ppm and 68.9ppm, which the Venkateswarlu group attributes to the epoxide carbons.

Conclusion

13C NMR prediction using DFT GIAO method with mPW1PW91/6-31G(d,p) provides unequivocal confirmation that the Nakata group has synthesised the nominal epoxyafricane and the Venkateswarlu group has assigned the wrong structure to their observed NMR data. Exhaustive calculation of the chemical shift of all diastereoisomers of epoxyafricane, as well as possible isomerisation product, shows that the chemical shift at 82.6 ppm and 68.9 cannot be attributed to epoxide carbon. It is likely that a structural isomer of epoxyafriane was isolated.

It is also interesting to note that reported proton and carbon chemical shift [24] of diol 15 matches almost exactly the "epoxyafricane" isolated by the Venkateswarlu group. In addition, the optical rotation and melting point are also congruent with those reported by the Venkateswarlu group. However, the absence of OH stretch is rather strange, and the elemental analysis does not agree with the diol.

References

- ↑ K. Alder, G. Stein, "Untersuchungen über den Verlauf der Diensynthese", Angewandte Chemie, 1937,50, 510-519, DOI:10.1002/ange.19370502804

- ↑ R. Hoffmann, R. B. Woodward, "Conservation of orbital symmetry", Accounts of Chemical Research, 1968,1, 17-22, DOI:10.1021/ar50001a003

- ↑ N. L. Allinger, "Conformational analysis. 130. MM2. A hydrocarbon force field utilizing V1 and V2 torsional terms", Journal of the American Chemical Society, 1977,99, 8127-8134, DOI:10.1021/ja00467a001

- ↑ S.W. Elmore, L. A. Paquette, "The first thermally-induced retro-oxy-cope rearrangement", Tetrahedron Letters, 1991,32, 319-322, DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0

- ↑ P. M. Warner, "Strained bridgehead double bond", Chemical Reviews, 1989,89, 1067-1093, DOI:10.1021/cr00095a007

- ↑ W. F. Maier, P. V. R. Schleyer, "Evaluation and prediction of the stability of bridgehead olefins", Journal of the American Chemical Society, 1981,103, 1891-1900, DOI:DOI: 10.1021/ja00398a003 DOI: 10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ W. L. Mock, "The reactivity of noncoplanar double bonds", Tetrahedron Letters, 1972,13, 475-478, DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)84354-9

- ↑ I. Novak, "Molecular Modeling of Anti-Bredt Compounds", Journal of Chemical Information and Modelling, 2005,45, 334-338, DOI:10.1021/ci0497354

- ↑ B. Halton, S. G. G. Russell, " π-Selective dichlorocyclopropanation and epoxidation of 9-chloro-1,4,5,8-tetrahydro-4a,6a-methanonaphthalene. Controlled synthesis of the C-9 epimers of (1a-α,2a-α.,6a-α.,7a-α)-1,8,8-trichloro-1a,2,3,6,7,7a-hexahydro-2a,6a-methanocyclopropa[b]naphthalene", Journal of Organic Chemistry, 1991,56, 5553-5556, DOI:10.1021/jo00019a015

- ↑ K. B. Wiberg, "Bent Bonds in Organic Compounds", Accounts of Chemical Research, 1996,29, 229-234, DOI:10.1021/ar950207a

- ↑ S. Winstein, R. E. Buckles, "The Role of Neighboring Groups in Replacement Reactions. I. Retention of Configuration in the Reaction of Some Dihalides and Acetoxyhalides with Silver Acetate", Journal of the American Chemical Society, 1942,64, 2780-2786, DOI:10.1002/ange.19370502804

- ↑ A. d. C. Coronel, C. M. Cerda-Garcia-Rojas, P. Joseph-Nathan, C. A. N. Catalan, "Chemical Composition, seasonal variation and a new sesquiterpene alcohol from the essential oil of lippa intergrifolia", Flavour and Fragrance Journal, 2006, 21, 839–847 DOI:10.1002/ffj.1736

- ↑ J. C. Braekman, D. Daloze, B. Tursch, S. E. Hall, J. P. Declereq, G. Germain, M. V. Meerssche, "Δ9(15)-Africanene, a new sesquiterpene hydrocarbon from the soft coral Sinularia erecta", Experimentia Journal, 1980, 36, 891-892 DOI:10.1007/BF019537756

- ↑ P. Ramesh, N. Srinivasa Reddy, T. P. Rao, Y. Venkateswarlu, "New Oxygenated Africanenes from the Soft Coral Sinularia dissecta", Journal of Natural Products, 1999, 62, 1019-1021 DOI:10.1021/np980449u

- ↑ Y. Matsuda, Y. Endo, Y. Saikawa, M. Nakata, "Synthetic Studies on Polymaxenolides: Synthesis and Structure Elucidation of Nominal Epoxyafricanane and Other Africane-Type Sesquiterpenoids", Journal of Organic Chemistry, 2011, 76, 6258-6263 DOI:10.1021/jo2010186

- ↑ D.C Braddock, H. S. Rzepa, "Structural Reassignment of Obtusallenes V, VI, and VII by GIAO-Based Density Functional Prediction", Journal of Natural Products, 2008, 71, 728-730 DOI:10.1021/np0705918

- ↑ S. D. Rychnovsky, "Predicting NMR Spectra by Computational Methods: Structure Revision of Hexacyclinol", Organic Letters, 2006, 8, 2895-2898 DOI:10.1021/ol0611346

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 G. Saielli, K. C. Nicolaou, A. Ortiz, H. Zhang, A. Bagno, "Addressing the Stereochemistry of Complex Organic Molecules by Density Functional Theory-NMR: Vannusal B in Retrospective", Journal of American Chemical Society, 2008, 71, 728-730 DOI:10.1021/np0705918

- ↑ M. W. Lodewyk, D/ J. Tantillo, "Prediction of the Structure of Nobilisitine A Using Computed NMR Chemical Shifts", 2011, 74, 1339-1343 DOI:10.1021/np2000446

- ↑ H. Hart, J. L. Corbin , "Conformations of Seven-Membered Rings. Benzocycloheptenes", Journal of American Chemical Society, 1965, 87, 3135–3139 DOI:10.1021/ja01092a023

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 S. G. Smith and J. M. Goodman, "Assigning Stereochemistry to Single Diastereoisomers by GIAO NMR Calculation: The DP4 Probability", Journal of American Chemical Society, 2010, 132, 12946–12959 DOI:10.1021/ja105035r

- ↑ S. G. Smith and J. M. Goodman, "Assigning the Stereochemistry of Pairs of Diastereoisomers Using GIAO NMR Shift Calculation", Journal of Organic Chemistry, 2009, 74, 4597-4607 DOI:10.1021/jo900408d

- ↑ N. S. Reddy, T. V. Goud and Y. Venkateswarlu, "Acid catalysed rearrangement of Δ9,15-africanene: a cytotoxic sesquiterpene", Journal of Chemical Research (S), 2000, 438-439

- ↑ A. S. R. Anjaneyulu, P. M. Gowri, M. V. R. Krishna Murthy, "New Sesquiterpenoids from the Soft Coral Sinularia intacta of the Indian Ocean", Journal of Natural Products, 1999, 62, 1600-1604 DOI:10.1021/np9901480