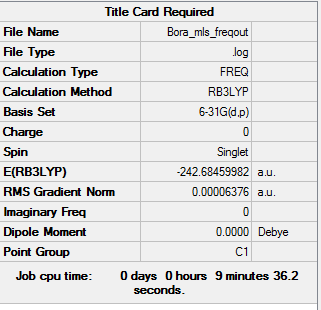

Rep:Mod:mlsinorgcomp

Inorganic Computational Experiment- By Megan Shipton: Week One

EX3 Optimisation

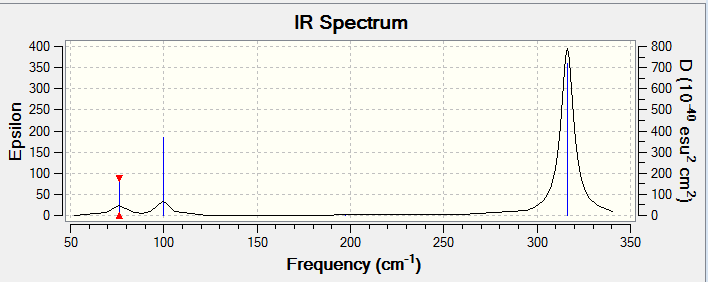

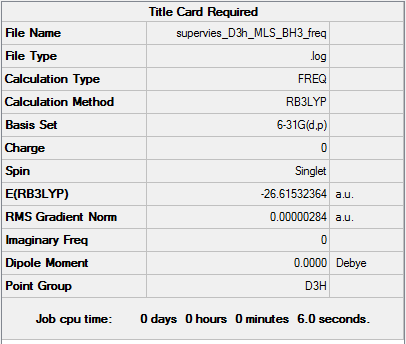

BH3

The optimisation log file is here

The optimisation log file is here

| Summary data | Convergence data | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000012 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000008 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000064 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000039 0.001200 YES |

|

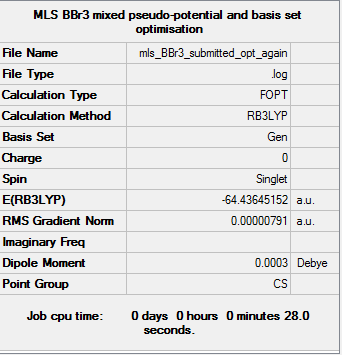

BBr3

The optimisation log file is here. DOI:10042/85279

| Summary data | Convergence data | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000014 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000006 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000057 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000038 0.001200 YES |

|

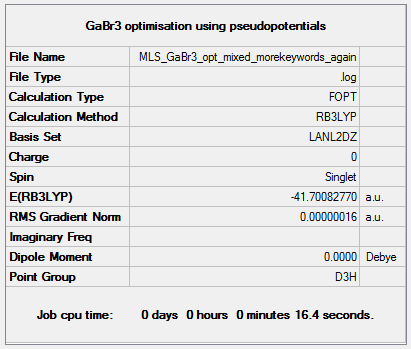

GaBr3

The optimisation log file is here. DOI:10042/85122

| Summary data | Convergence data | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000000 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000000 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000003 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000002 0.001200 YES |

|

EX3 Structures

| BH3 | BBr3 | GaBr3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| r(E-X)/Å | 1.19 | 1.93 | 2.35 |

| θ(X-E-X)/degrees | 120.0 | 120.0 | 120.0 |

By comparing BBr3 and GaBr3 we can investigate the effect of changing the central atom.

Boron and gallium are both elements in group 13 meaning they have the same number of valence electrons used for bonding (B: [He] 2s2 2p1, Ga: [Ar] 3d10 4s2 4p1). Because gallium is so much larger, its orbitals will be more diffuse and unable to overlap as efficiently with ligand orbitals leading to weaker bonding. Evidence for this can be seen by comparing the bond lengths above. The bond length for BBr3 is shorter than that of GaBr3 providing evidence for boron forming stronger bonds than gallium with the bromine atoms.

Boron is a lighter element in row 2 (with an atomic mass of 10.8) while gallium is a heavier element in row 4 (with an atomic mass of 69.7). A consequence of a heavier atom is that the frequency of IR vibrations decreases. higher IR frequencies are produced when the atoms are light and the bonds between them are strong.

frequency (Hz)= (f/(m1m2/m1+m2))^0.5/2π, where m1 and m2 are the masses of the atoms, f is the bond force constant.

Gallium and boron are both not very electronegative (boron has electronegativity= 2.04 while gallium has electronegativity= 1.81)[1] Gallium is less electronegative than boron though. The difference between the electronegativities of boron and bromine will be less than the difference in electronegativities between gallium and bromine (electronegativity of bromine: 2.96).[1] This means that the bonds in the gallium compound will be more polarised than the bonds of the boron compound.

By comparing BH3 and BBr3 we can investigate the effect of changing the ligand.

Hydrogen is a much smaller, lighter element than bromine (hydrogen has a mass of 1.0 and bromine has a mass of 79.9). However both elements only require one more electron to obtain a full electron shell (H: 1s1, Br[Ar] 3d10 4s2 4p1).

The bond between boron and bromine should be weaker because bromine orbitals are larger and more diffuse than hydrogen orbitals. This and the fact that bromine has a larger mass will contribute to the IR vibrational frequencies being less for the bromine compound.

The electronegativity of hydrogen is 2.20.[1] The difference is larger in electronegativities for boron tribromide meaning that these bonds will be more polar than those of borane.

A bond is an attraction between two or more atoms generated by the interactions of the valence electrons. In ionic bonding the electrons are completely transferred from one atom to another resulting in the formation of positive and negative ions. Covalent bonding consists of valence electrons being shared between the atoms. Covalent bonding becomes polar when the electrons are not shared between atoms equally due to differences in electronegativity. The greater the electronegativity of an element, the more it will attract bonded electrons toward it.

Guassview displays bonds only if they are within a predetermined value range included in the software. Even if the bonds are not displayed there is still attraction between the atoms (bonds).

Typical strong bonds include oxygen-oxygen double bonds (743 kJ/mol), nitrogen-nitrogen triple bonds (946 kJ/mol) and carbon-carbon double bonds (612 kJ/mol). Medium strength bonds can include examples such as carbon-carbon single bonds (348 kJ/mol), bromine- hydrogen single bonds (366 kJ/mol), and carbon-hydrogen single bonds (412 kJ/mol). Weak bonds can include examples such as nitrogen-nitrogen single bonds (146 kJ/mol), oxygen-chlorine single bonds (203 kJ/mol) and carbon-iodine single bonds (238 kJ/mol). These bond energies given are the mean bond enthalpies.[2]

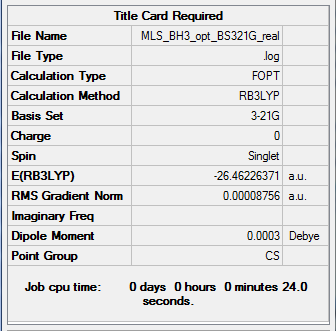

Analysis of BH3

Frequency analysis

Frequency calculation log is here.

| Summary data | Frequencies |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -12.3889 -12.3823 -7.7287 -0.0007 0.0237 0.4048 Low frequencies --- 1162.9692 1213.1354 1213.1356 |

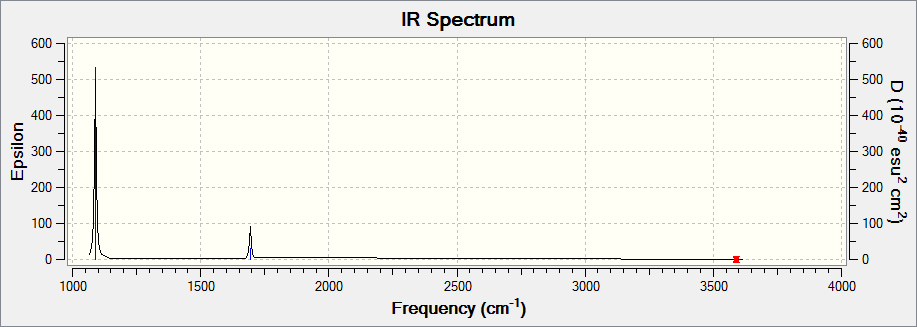

Vibrational spectrum of BH3

| frequency | IR intensity | IR active? | type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1163 | 93 | yes | bend (umbrella) |

| 1213 | 14 | slightly | bend |

| 1213 | 14 | slightly | bend |

| 2583 | 0 | no | stretch |

| 2716 | 126 | yes | stretch |

| 2716 | 126 | yes | stretch |

Why are there fewer IR signals displayed in the spectrum than the reported number of signals in the table? IR spectroscopy requires a change in dipole moment in a vibration in order for the vibration to be detected (IR active). Not all of the signals in the table are IR active and will not show up in the spectrum. Another reason for the fewer signals to be present in the spectrum is the degenerate energies of some of the different vibrations. These signals will overlap and in doing so reduce the number of visible signals.

Molecular Orbital Diagram of BH3

The LCAO MOs and the computed MOs can be in general quite easily recognised as displaying the same thing and matched. The computed MOs are more diffuse and sometimes form shapes hard to recreate with LCAO.

LCAO as a method doesn't require a computer and can give a fairly accurate representation of the molecular orbitals of a compound. Computational methods will be able to match the reality of electron distribution more closely than the LCAOs howver, as they are able to take into account more contributing factors to MO shape and are not based on as many assumptions as LCAO.[3]

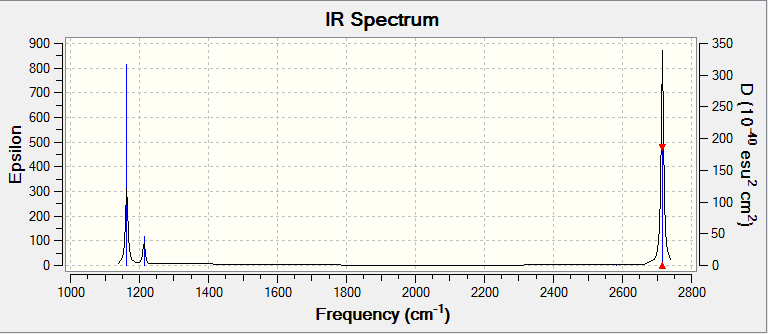

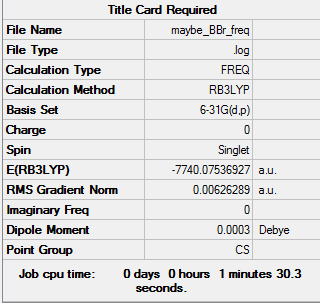

Analysis of BBr3

Frequency calculation is here. DOI:10042/104395

| Summary data | Frequencies |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- 0.0035 0.0134 0.0144 33.6716 33.7147 33.8321 Low frequencies --- 148.4585 148.5057 259.1258 |

| frequency | IR intensity | IR active? | type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 148 | 0 | no | bend |

| 149 | 0 | no | bend |

| 259 | 0 | no | stretch |

| 401 | 2 | slightly | bend (umbrella) |

| 745 | 292 | yes | stretch |

| 745 | 292 | yes | stretch |

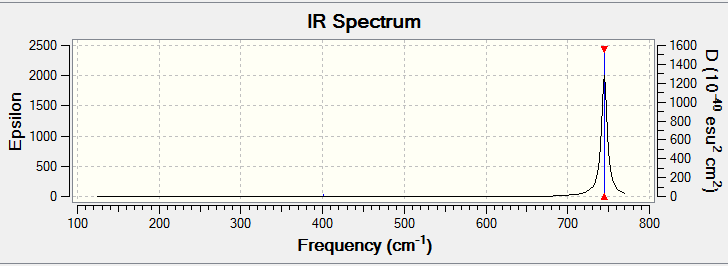

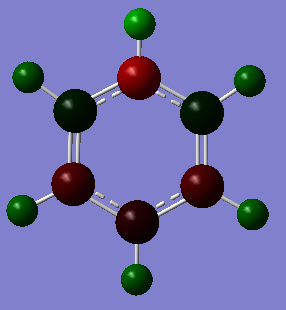

Analysis of GaBr3

Frequency calculation log is here.DOI:10042/90566

| Summary data | Frequencies |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -1.4878 -0.0015 -0.0002 0.0096 0.6540 0.6540 Low frequencies --- 76.3920 76.3924 99.6767 |

| frequency | IR intensity | IR active? | type | symmetry |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 76 | 3 | slightly | bend | e' |

| 76 | 3 | slightly | bend | e' |

| 100 | 9 | slightly | bend (umbrella) | a' ' |

| 197 | 0 | no | stretch | a' |

| 316 | 57 | yes | stretch | e' |

| 316 | 57 | yes | stretch | e' |

The large difference in the value of frequencies for BH3 and GaBr3 indicates a the difference in mass as well as the strength of the bonds between the atoms. The umbrella mode for BH3 appears at the frequency 1163 with intensity 93 while in GaBr3 the umbrella mode appears at the frequency 100 with intensity 9. This mode is also the mode with the lowest frequency for borane but it falls in the middle of the range of frequencies for gallium tribromide. The vibrational calculation gives a force constant of 21.9 N/m for GaBr3 and 72.9 N/m for BH3. This indicates that the boron-hydrogen bond is stronger than the gallium-bromide bond. When the displacement vectors are observed during the vibration animation in Gaussian, it is possible to see that in borane the vibration is the result of movement from mostly the hydrogen atoms whereas in gallium tribromide it is the central gallium. This is probably due to the differences of mass of the atoms involved in the molecule (a boron atom has approximately ten times the mass of a hydrogen atom making hydrogen much easier to move in the vibration, a gallium atom on the other hand does not have as much mass as one bromine atom and would be relatively easy to move in the vibration).

The first set of low frequencies is caused by the movement of the central atom of the molecule. The closer to zero, the more accurate the other frequencies. The other set of low frequencies are caused by the movement of the ligand atoms of the molecule.

The same method is required for calculations in order to make meaningful comparisons. This is because the calculations will then have the same intrinsic error in the method. The purpose of carrying out frequency analysis is to enable bond strength to be observed by calculating the force constant and to show the different vibrations of the molecule.

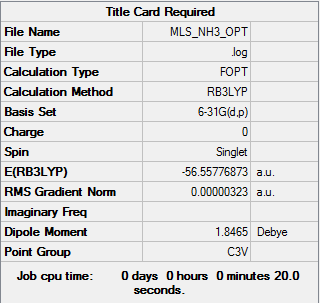

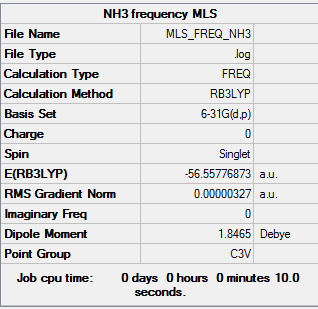

Analysis of NH3

Optimisation calculation log is here.

| Data summary | Convergence data | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000006 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000004 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000012 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000008 0.001200 YES |

|

Frequency calculation log is here.

| Summary data | Frequencies |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -0.0126 -0.0022 0.0019 7.1669 8.1602 8.1605 Low frequencies --- 1089.3837 1693.9369 1693.9369 |

| frequency | IR intensity | IR active? | type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1089 | 145 | yes | bend (umbrella) |

| 1694 | 14 | slightly | bend |

| 1694 | 14 | slightly | bend |

| 3461 | 1 | no | stretch |

| 3590 | 0 | no | stretch |

| 3590 | 0 | no | stretch |

Molecular orbital calculation log is here.

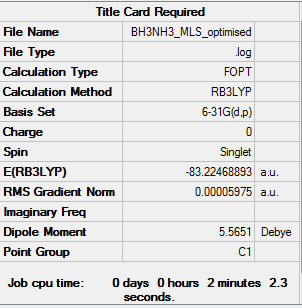

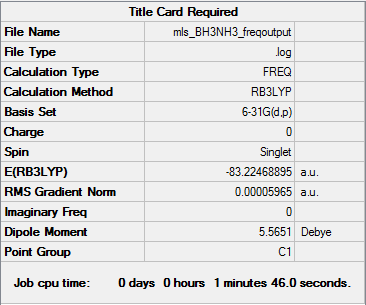

NH3BH3 Analysis

Optimisation calculation log is here.DOI:10042/93779

| Summary data | Convergence data | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000122 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000058 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000513 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000296 0.001200 YES |

|

Frequency analysis calculation log is here. DOI:10042/104260

| Summary data | Frequencies |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -0.0016 -0.0008 -0.0006 17.1660 17.5746 37.3520 Low frequencies --- 265.9185 632.2125 639.3528 |

| Molecule | Energy/au |

|---|---|

| BH3 | -26.6153236 |

| NH3 | -56.55776873 |

| NH3BH3 | -83.22468893 |

Dissociation energy ΔE=E(NH3BH3)-[E(NH3)+E(BH3)]= -0.0515966 au =-135.47 kJ/mol

By comparing this to the earlier listed examples of bond strengths I would determine this bond to be a weak bond.

Week two: Aromaticity

Benzene analysis

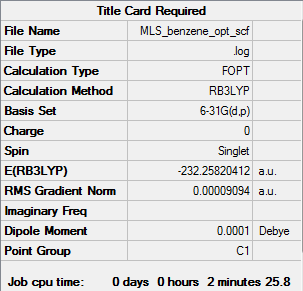

Benzene optimisation

Optimisation calculation is here.DOI:10042/104121

| Summary data | Convergence data | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000198 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000082 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000849 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000305 0.001200 YES |

|

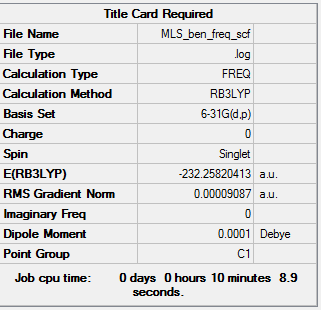

Benzene frequency analysis

Frequency calculation is here. DOI:10042/104202

| Summary data | Frequencies |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -13.7745 -12.9692 -11.9111 -0.0002 0.0005 0.0010 Low frequencies --- 414.0701 414.1918 620.9706 |

Benzene energy analysis

The energy calculation log file is here. DOI:10042/110647

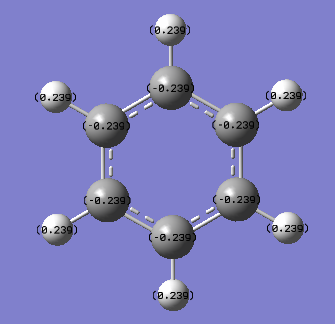

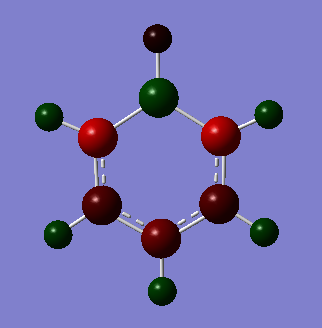

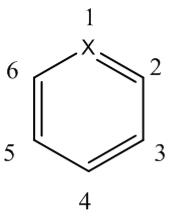

It can clearly be seen in the coloured NBO charge distribution picture of benzene that the carbon atoms have a slight negative charge (as they are red) and the hydrogen atoms have a slight positive charge (as they are green). The atoms of each element also appear to be uniform in colour indicating that each atom has a very similar dipole charge as the other atoms of the same element within benzene. Both the allocation of positive and negative dipoles and the uniform charge distribution around each element in the ring can be confirmed by the assigned numbers of the NBO analysis. All of the carbon atoms have an atomic charge of -0.239 while all of the hydrogen atoms have an atomic charge of +0.239. This charge distribution is to be expected because of the differences in electronegativities of the carbon and hydrogen. The more electronegative carbon (2.55) will attract electrons in the bond more than the less electronegative hydrogen (2.20).[1]

The difference in electronegativity values is not very large so only a small difference in electron distribution would be expected between the two elements (as observed). The very symmetrical structure (D6h point group) would also make the uniform charge distribution be expected as each atom of a particular element is in an identical environment to the others in benzene.

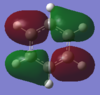

Benzene molecular orbital diagram

How do these MOs relate to the common conception of aromaticity? Hint 2: aromaticity relates to delocalisation. Hint 3: aromaticity relates to the total pi electron density, and MOs contain formally only 2 electrons each.

The molecular orbitals depicted below are some of the non-core molecular orbitals of benzene generated by Gaussian. The LCAOs were constructed upon inspection of the computed MOs. It should also be noted that orbitals have been deemed to be degenerate if their energies are approximately the same (Gaussian has produced some MOs that differ only in the final decimal place for their energy value and these have been labelled degenerate to each other.

| MO | Computed energy | Occupied? | Computed MO | LCAO | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | -0.84678 | yes |  |

|

This bonding molecular orbital is formed by the in phase overlap of all of the hydrogen atom 1s orbitals and the carbon atom 2s orbitals. The MO has no nodes. This MO contributes to the formation of the sigma framework of the ring. |

| 8 | -0.74005 | yes |  |

|

This bonding MO is degenerate with MO 9. It is formed by the overlap of the carbon 2s orbitals and the hydrogen 1s orbitals. There is a nodal plane crossing the molecule intersecting atoms in the ring. This MO contributes to the formation of the sigma framework. |

| 9 | -0.74005 | yes |  |

|

This bonding MO is degenerate with MO 8. It is also formed by the overlap of the carbon 2s orbitals and the hydrogen 1s orbitals and possesses a nodal plane although this node bisects bonds on either side of the ring rather than atoms. This MO also contributes to the sigma framework. |

| 10 | -0.59740 | yes |  |

|

This bonding MO is degenerate with MO 11. It is formed by the overlap of carbon 2s and 2p orbitals with hydrogen 1s orbitals. It possesses two nodal planes, one bisecting bonds in the ring, one bisecting atoms. This MO also contributes to the sigma framework. |

| 11 | -0.59740 | yes |  |

|

This bonding MO is degenerate with MO 10. It is also formed with carbon 2s, 2p and hydrogen 1s orbitals and also has two nodal planes. Both nodes cross atoms in the ring however. This MO also contributes to the sigma framework. |

| 12 | -0.51795 | yes |  |

|

This bonding MO is formed by the overlap of carbon 2p orbitals with hydrogen 1s orbitals. It possesses one circular node around the ring. This MO also contributes to the sigma framework. |

| 13 | -0.45822 | yes |  |

|

This bonding MO is formed by the overlap of carbon 2s and hydrogen 1s orbitals. It has 3 nodal planes bisecting the bonds in the ring. This MO also contributes to the sigma framework. |

| 14 | -0.43854 | yes |  |

|

This bonding MO is formed by the overlap of carbon 2p orbitals. It has three nodal planes bisecting all of the atoms in the ring. This MO also contributes to the sigma framework. |

| 15 | -0.41657 | yes |  |

|

This bonding MO is degenerate with MO 16. It is formed by the overlap of carbon 2p and 1s hydrogen orbitals. It has a circular node around the carbon ring and a nodal plane bisecting bonds on the ring. This MO also contributes to the sigma framework. |

| 16 | -0.41656 | yes |  |

|

This bonding MO is degenerate with MO 15. It is also formed from carbon 2p and 1s hydrogen orbitals. The MO has four nodes. It also contributes to the sigma framework. |

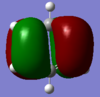

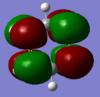

| 17 | -0.35998 | yes |  |

|

This bonding MO is formed from 2p carbon orbitals perpendicular to the plane of the ring. It has one nodal plane (the plane of the ring of atoms). This molecular orbital contributes to the delocalised pi system (specifically this MO contributes to delocalisation around the entire ring). |

| 18 | -0.33962 | yes |  |

|

This bonding MO is degenerate with MO 19. It is formed from the overlap of carbon 2p orbitals in the plane of the ring and 1s hydrogen orbitals. There are four nodal planes: two bisecting the benzene ring vertically (through atoms) and horizontally (through bonds), and two running parallel to the vertical bonds on the sides of the ring. This MO contributes to the sigma framework. |

| 19 | -0.33960 | yes |  |

|

This bonding MO is degenerate with MO 18. It is also formed from the overlap of carbon 2p orbitals in the plane of the ring and 1s hydrogen orbitals. There are four nodes in this MO. It contributes to the sigma framework. |

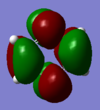

| 20 | -0.24691 | yes |  |

|

This bonding MO is degenerate with MO 21. It is formed by the overlap of carbon 2p orbitals perpendicular to the ring of atoms. This MO has two nodal planes: one bisecting the ring (cutting through bonds) and one along the plane of the ring. It contributes to the conjugated pi system (specifically contributing to delocalisation on the top and bottom half of the molecule). This MO and MO 21 are the benzene’s highest occupied molecular orbitals. |

| 21 | -0.24691 | yes |  |

|

This bonding MO is degenerate with MO 20. It is formed by the overlap of carbon 2p orbitals perpendicular to the ring of atoms. This MO has two nodal planes: one bisecting the ring (cutting through atoms) and one along the plane of the ring. It contributes to the conjugated pi system (specifically contributing to delocalisation on the left and right sides of the molecule). This MO and MO 20 are the benzene’s highest occupied molecular orbitals. |

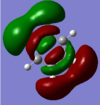

| 22 | 0.00267 | no |  |

|

This antibonding MO is degenerate with MO 23. It is formed by the overlap of carbon 2p orbitals perpendicular to the ring of atoms. This MO has three nodal planes: two bisecting the ring (one cutting through atoms vertically, one cutting through bonds horizontally) and one node along the plane of the ring. It makes up part of the delocalised pi orbital above and below the ring (although this antibonding MO is unoccupied). This MO and MO 23 are the benzene’s lowest unoccupied molecular orbital. |

| 23 | 0.00268 | no |  |

|

This antibonding MO is degenerate with MO 22. It is formed by the overlap of carbon 2p orbitals perpendicular to the ring of atoms. This MO has three nodal planes: two bisecting the ring (both bisecting the ring diagonally through bonds) and one node along the plane of the ring. It makes up part of the delocalised pi orbital above and below the ring (although this antibonding MO is unoccupied). This MO and MO 22 are the benzene’s lowest unoccupied molecular orbital. |

| 24 | 0.09117 | no |  |

|

This antibonding MO is formed by the overlap of carbon 2p orbitals in the plane of the ring and hydrogen 1s orbitals. The MO has two circular nodes: one between the carbon and hydrogen atoms and one at the ring. It makes up part of the sigma framework (although this antibonding MO is unoccupied). |

| 25 | 0.14516 | no |  |

|

This antibonding MO is degenerate with MO 26. It is formed by the overlap of carbon 2p orbitals in the plane of the ring and hydrogen 1s orbitals. The MO has three nodes. There are two circular nodes: one between the carbon and hydrogen atoms and one at the ring, and a nodal plane bisecting the ring (diagonally through atoms). It makes up part of the sigma framework (although this antibonding MO is unoccupied). |

| 26 | 0.14517 | no |  |

|

This antibonding MO is degenerate with MO 25. It is formed by the overlap of carbon 2p orbitals in the plane of the ring and hydrogen 1s orbitals. The MO has three nodes. There are two circular nodes: one between the carbon and hydrogen atoms and one at the ring, and a nodal plane bisecting the ring (diagonally through bonds). It makes up part of the sigma framework (although this antibonding MO is unoccupied). |

| 27 | 0.16190 | no |  |

|

This antibonding MO is formed by 2p carbon orbitals perpendicular to the plane of the ring. These orbitals are all out of phase. There are three nodal planes in this MO: each bisecting the benzene ring through bonds. |

There were three occupied molecular orbitals that contribute to the delocalised pi system: MOs 17, 20 and 21. The delocalisation of mobile electrons in a cyclic system is a defining feature of aromaticity.[4] These MOs that allow electrons to be shared around the ring produce an aromatic system. Formally each molecular orbital can hold two electrons so these three molecular orbitals account for the delocalised pi system consisting of 6 electrons that is known to be present in benzene.

Boratabenzene analysis

Boratabenzene is an analogue of benzene which has had one of the C-H units in the ring replaced with a B-H and negative a charge added. Without this negative charge the compound is known as borabenzene. Boratabenzne is isoelectronic with benzene but borabenzene has fewer valence electrons and because of this is unstable. Free borabenzene has not been isolated yet because its electron deficiency enables easy interaction with stabilising Lewis bases. [5]

Boratabenzene Optimisation

Optimisation file is here. DOI:10042/104220

| Summary data | Convergence data | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000441 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000087 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.001788 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000556 0.001200 YES |

|

Boratabenzene frequency analysis

Frequency calculation log is here. DOI:10042/104158

| Summary data | Frequencies |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- 0.0003 0.0006 0.0006 2.6077 7.2821 9.8934 Low frequencies --- 371.6012 404.5200 565.2411 |

Boratabenzene energy analysis

Energy calculation log is here. DOI:10042/110629

Pyridinium analysis

Pyridinium is an analogue of benzene which has had one of the C-H units in the ring replaced with a N-H unit. For the molecule to remain isoelectronic to benzene a positive charge was added.

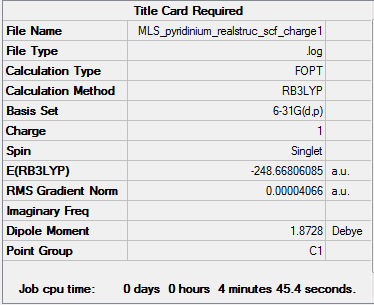

Pyridinium optimisation

Optimisation calculation file is here.DOI:10042/101594

| Summary data | Convergence data | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000048 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000020 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000657 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000158 0.001200 YES |

|

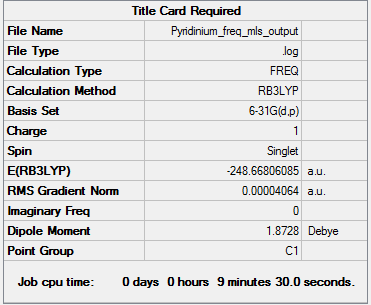

Pyridinium frequency analysis

Pyridinium frequency calculation is here. DOI:10042/104238

| Summary data | Frequencies |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -9.2612 -4.3707 -0.0010 -0.0010 -0.0004 4.0193 Low frequencies --- 391.8855 404.3815 620.1941 |

Pyridinium energy analysis

Energy calculation of pyridinium is here. DOI:10042/110627

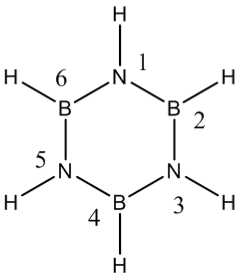

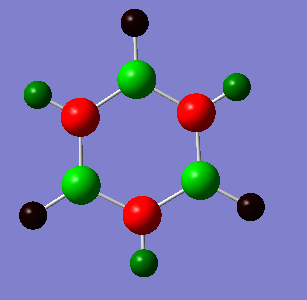

Borazine analysis

Borazine is an isoelectronic analogue of benzene for which the C-H units have been substituted for alternating N-H and B-H units. The electron deficient B-H units balance the excess electrons of the N-H units resulting in the structure remaining isoelectronic to benzene. According to the literature we expect borazine to have a lower resonance energy compare to benzene (22.1 kcal/mol for benzene and 11.1 kcal/mol for borazine).[4]

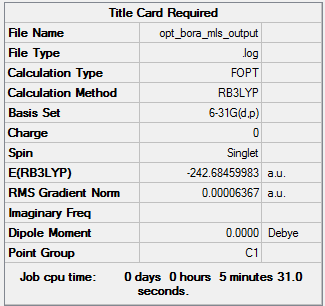

Optimisation of borazine

The optimisation calculation log is here. DOI:10042/111903

| Summary data | Convergence data | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000084 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000033 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000275 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000076 0.001200 YES |

|

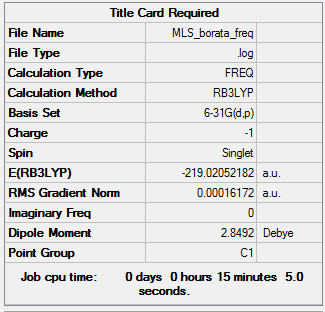

Frequency analysis of borazine

The frequency calculation log file is here. DOI:10042/111943

| Summary data | Frequencies |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -0.0005 0.0004 0.0008 3.0806 5.2472 8.6260 Low frequencies --- 289.6613 289.7983 404.4101 |

Energy analysis of borazine

The energy calculation log file is here. DOI:10042/112016

Investigation into borazine aromaticity has been carried out and shown that the increase in bond polarities in the ring (between the nitrogen and boron) resulted in a significant decrease in delocalisation of pi electrons. Some experimental techniques used to investigate borazine have even concluded that the pi electrons are localised at the more electronegative nitrogen atoms rather than delocalised (this becomes apparent when investigating nucleus-independent chemical shift).[4]

Comparison between the benzene analogues

Comparison of frequencies

The frequencies of these analogues are all within the same region and the mass of all of the atoms involved is comparable. Due to the similar masses of the atoms involved in the bonds it is plausible to speculate on bond strength based on the frequencies calculated for each analogue.

For stronger bonds we would expect higher frequency wavenumbers.

Benzene has the highest frequencies, indicating that the aromatic carbon carbon bonds are stronger than the heteroaromatic bonds. The carbon atoms will have the best overlap with other carbon atoms.

Pyridinium followed by boratobenzene are next for highest frequencies (they are quite close to one another). This suggests that the bonds are slightly weaker in these molecules.

Borazine has the lowest frequencies indicating that this is the analogue with the weakest bonds. This supports the idea that the alternating electronegative and electropositive atoms has prevented most, if not all of the delocalision of the pi system, rendering the molecule not aromatic (thereby removing aromaticity's stabilising influence on the molecule making the bonds weaker).

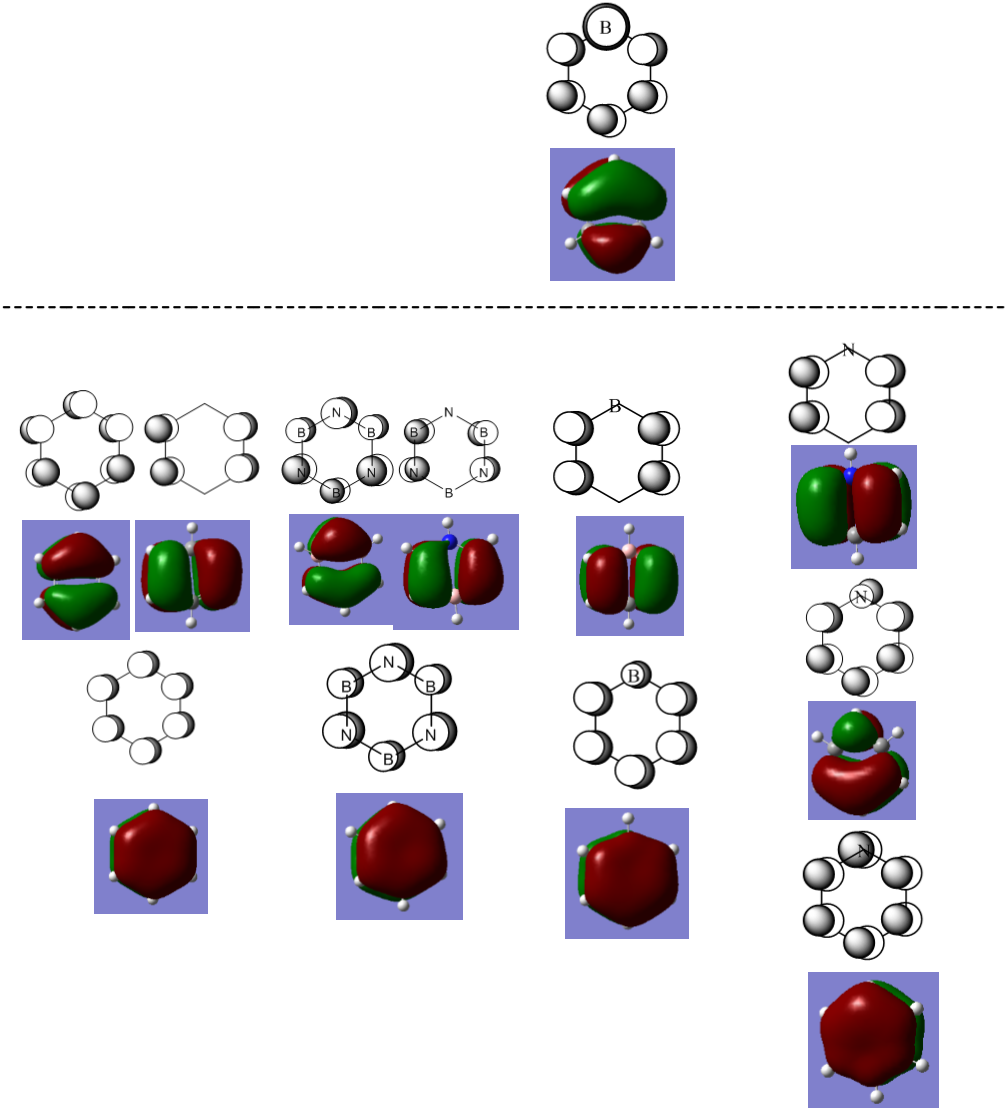

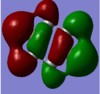

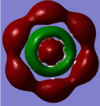

Comparison of molecular orbitals

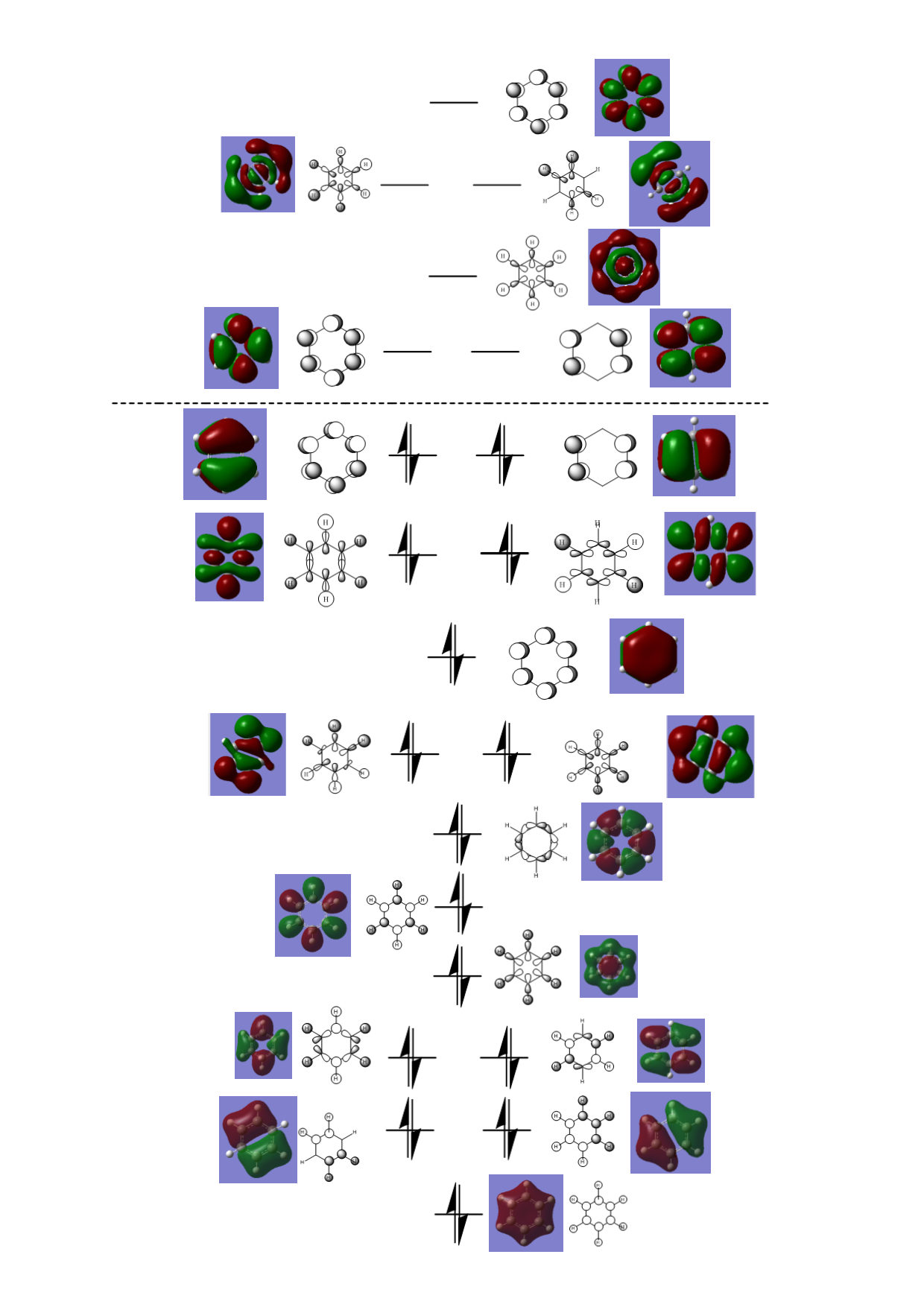

Comparing the molecular orbitals that contribute to the delocalised pi system. From left to right: benzene, borazine, boratabenzene and pyridinium.

Benzene has two degenerate orbitals as its HOMO. This degeneracy is lost for the equivalent molecular orbitals of pyridinium and boratabenzene. The reason for the lost degeneracy in the benzene analogues is the loss of symmetry. Both pyridinium and boratabenzene have symmetry point group Cs while benzene has symmetry point group D6h. Borazine, while not as symmetrical as benzene, is more symmetrical than pyridinium and boratabenzene (it possesses the point group D3h. Due to the symmetry of each molecule one would expect benzene to have the greatest number of degenerate molecular orbitals and pyridinium and boratabenzene to have the least number of degenerate orbitals (with borazine having number of degenerate MOs between these two extremes of symmetry).

In benzene, both of these HOMO molecular orbitals have the same energy and are weakly bonding (they are the final bonding orbitals).

In boratabenzene, only one of the benzene HOMO equivalent MOs is bonding (MO number 20, depicted below the dotted lie in the figure above). The other benzene HOMO equivalent MO, MO number 21, is an occupied weakly anti-bonding MO (the first antibonding orbital). For this MO the orbital contribution from boron is larger than the orbital contribution from carbon. The opposite is observable in pyridinium for which the same benzene HOMO equivalent MO that became an antibonding orbital in boratabenzene became a bonding MO in pyridinium(and lower in energy than the other benzene HOMO equivalent when degeneracy was lost). It is possible to see that the orbital contribution of nitrogen in this MO is smaller than the contributions of carbon.

By comparing the MOs of the analogues for which all of the p orbitals are in phase out of the plane of the ring we can observe some of differences in electron distribution. In benzene the orbital contributions are totally equal (as expected). For borazine it is possible to observe indentations in the MO where the boron atoms are placed in the ring and bulges where the nitrogen atoms are placed. This shows how nitrogen is more electronegative and attracts a larger portion of the delocalised electrons than boron. This exact same feature can be observed in pyridinium (which has a larger contribution from the nitrogen orbital than the carbon atoms) and boratabenzene (which has a smaller contribution from the boron orbital than the carbon atoms).

The benzene HOMO that includes electron density on either side of the ring retains its shape quite well when the equivalents MOs are expressed in the analogues. This is with the exception of borazine which has the electron density warped away from boron and towards nitrogen.

For benzene, the two HOMOs are the last bonding orbitals. The HOMO of boratabenzene is higher in energy, even becoming antibonding. The pyridinium HOMO is deeper in energy than benzene and there are several unoccupied bonding MOs available after the HOMO. The borazine HOMOs, like benzene, are the last bonding orbitals. In all pyridinium seems to be the lowest in energy, boratabenzene the highest in energy, and benzene comparable with borazine (with borazine being perhaps slightly lower in energy).

Comparison of NBO charge distribution

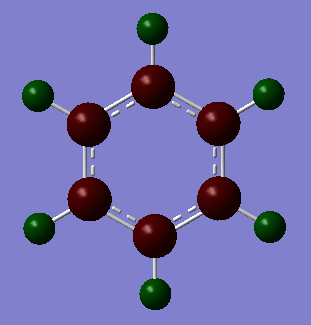

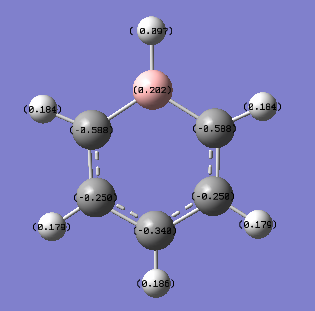

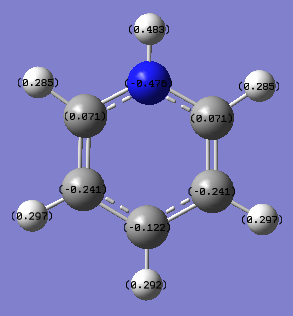

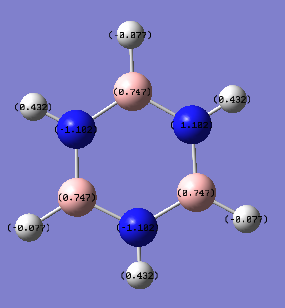

The coloured NBO charge distribution images all use the same colour scale (-1.00 to 1.00 atomic charges for brightest red to brightest green).

| Boratabenzene | Benzene | Pyridinium | Borazine |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Position on molecule | Boratabenzene | Benzene | Pyridinium | Borazine |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (X or N) | 0.202 (X=B) | -0.239 (X=C) | -0.476 (X=N) | -1.102 (N) |

| 1 (H) | 0.097 | 0.239 | 0.483 | 0.432 |

| 2 (C or B) | -0.588 | -0.239 | 0.071 | 0.747 |

| 2 (H) | 0.184 | 0.239 | 0.285 | -0.077 |

| 3 (C or N) | -0.250 | -0.239 | -0.241 | -1.102 |

| 3 (H) | 0.179 | 0.239 | 0.297 | 0.432 |

| 4 (C or B) | -0.340 | -0.239 | -0.122 | 0.747 |

| 4 (H) | 0.186 | 0.239 | 0.292 | -0.077 |

| 5 (C or N) | -0.250 | -0.239 | -0.241 | -1.102 |

| 5 (H) | 0.179 | 0.239 | 0.297 | 0.432 |

| 6 (C or B) | -0.588 | -0.239 | 0.071 | 0.747 |

| 6 (H) | 0.184 | 0.239 | 0.285 | -0.077 |

In benzene the carbon atoms are uniformly slightly negatively charged while in the benzene analogues the charge distribution varies around the ring. For pyridinium and boratabenzene the charge distribution varies symmetrically (environment 2 is equivalent to environment 6, and environment 3 is equivalent to environment 5).

In boratabenzene the negative charge is predominantly localised on the carbon atoms ortho to the boron (environment 2/5, NBO charge= -0.588) and to a lesser extent on the carbon atom para to the boron (environment 4, NBO charge= -0.340). Even the least negatively charged carbon atoms in boratabenzene (those meta to the boron atom, environment 3/5, NBO charge= -0.250) have a greater negative charge than the carbon atoms of benzene (NBO charge= -0.239). This is because carbon is a more electronegative element than boron (2.55 for carbon compared to 2.04 for boron).[1]

The charge on the boron atom itself is positive (NBO charge= 0.202). In this system, due to boron's lower electronegativity and negative charge, the atom will act as an electron donating group and will direct electron density to ortho and para positions in the aromatic ring.

The opposite case is true for pyridinium as the carbon atoms ortho to the nitrogen atom are positively charged (environment 2/6, NBO charge= 0.071) and the negative charge on the carbon para to the nitrogen is reduced from carbon's negative charge in benzene (environment 4, NBO charge= -0.122). Instead in this ring the electron distribution is concentrated more on the nitrogen atom (environment 1, NBO charge= -0.476). This is to be expected as nitrogen is more electronegative than carbon (electronegativity of nitrogen is 3.04 while carbon's is 2.55) and will attract the electrons in the ring more strongly.[1] The nitrogen atom acts as an electron withdrawing group in the aromatic ring because of its larger electronegativity and positive charge. For this reason it will direct electron density to the meta positions of the ring (environment 3/5, NBO charge= -0.241). This is observed as the NBO charge at these meta carbon atoms is slightly larger than the charge on a carbon atom in benzene. The resonance effects will also result in electron density being kept away from ortho and para carbon atoms (as clearly seen in the coloured diagram above).

In borazine the ring alternates B-H and N-H units. All nitrogen atoms have identical NBO charges and the hydrogen atoms attached to them also have uniform NBO charges. The same is true for the boron atoms and their attached hydrogens (the boron and nitrogen hydrogen atoms are different). The borazine has the largest difference in electron density throughout the molecule (as can be seen by the large NBO charge numbers and vibrant colours). The electronegative nitrogen atoms have a negative charge larger than one while the boron atoms have a positive charge of around 0.75. This indicates very polar bonds that would severely limit the aromaticity of the compound as the electrons are too attracted to the nitrogen atoms to delocalise to the neighbouring boron atoms and beyond. The charge distributions for nitrogen and boron in pyridinium and boratabenzene respectively are not even half the values for borazine. The alternating electronegative and weakly electron attracting atoms seems to have created wells for electron distribution at the nitrogen atoms.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Shriver and Atkins, Inorganic Chemistry, fifth ed. 2010, pp.30.

- ↑ Shriver and Atkins, Inorganic Chemistry, fifth ed. 2010, pp.60.

- ↑ J. A. Pople, Electron interaction in unsaturated hydrocarbons, 1953, pp, 1375-1385

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 P. von Rague Schleyer, H. Jiao, N. J. R. van Eikema Hommes, V. G. Malkin, O. L. Malkina, An evaluation of the aromaticity of inorganic rings, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 12669-12670

- ↑ B. Macha, Synthesis, characterization, and coordination of a boratabenzene-phosphine ligand with group 10 transition metals, 2012, pp.1-6