Rep:Mod:mikeillingworth

Data from Optimization

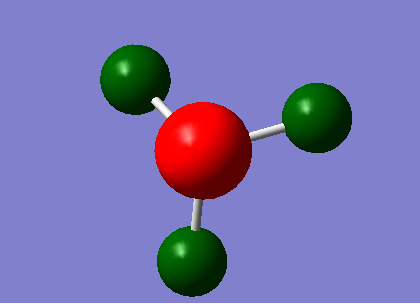

BH3

B3LYP/3-21G level

Optimisation log file available here

6-31G(d,p) level

| summary data | convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000157 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000074 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000576 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000478 0.001200 YES |

|

Optimization log file available here

GaBr3

B3LYP/LANL2DZ level

optimisation file: DOI:10042/90477

| summary data | convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000000 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000000 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000003 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000002 0.001200 YES |

|

Optimization log file available here

BBr3

Multiple basis sets

optimisation file: DOI:10042/90874

| summary data | convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000051 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000027 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000233 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000130 0.001200 YES |

|

Optimization log file available here

Geometry Data

| BH3 | BBr3 | GaBr3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| r(E-X) | 1.12 | 1.93 | 2.35 |

| θ(X-E-X) | 120.1 | 120.0 | 120.0 |

Above data uses the better calculation for BH3 where the 6-31G(d,p) basis set was used.

Structural Interpretation

When discussing and analysing the above results, there is a simple way to examine the bonds by invoking the argument of covalent radii of the constituent atoms.

When moving from BH3 to BBr3, the thing that has changed is the ligand. Br is a much larger atom than H, and so it stands to reason that it has a larger covalent radius. This would in turn mean that the bond B-Br would be larger than that of B-H simply due the the fact that Br is a larger atom, with more filled orbitals, and so will be further away from the B atom than an H would. The same logic can be applied when looking at the differences in bond length between BBR3 and GaBr3. Here, rather than the ligand changing, the central atom has increased in size, Ga is a group 13 element like B, however it is a much larger atom, and so similar to the reasoning above, it will have a larger covalent radius, causing the resultant bond to have a greater length.

Though this logic seems to match roughly with the data, there is a fundamental flaw in this reasoning. By only considering covalent radii of the atoms, we assume that the bonds are purely simple covalent bonds. There are 2 ways in which this could be untrue. Firstly, the bonds formed could possess ionic character, and so this would deviate the proposed bonding radii of the atoms, changing the length of the resultant bond. As well as this, we havent considered the possibility of pi stabilisation, which would similarly change the resulting bond lengths.

A chemical bond is an interaction between two atoms that is due to electrostatic forces. In the case of the molecules analysed above, the bonding is covalent. This is the sharing of electrons between the 2 atoms that cause dipolar interactions, linking the 2 atoms by a “bond.” A weak bond will have a bond energy somewhere in the region of any up to about 250KJ/mol, like heavier halogen diatoms (I-I, Br-Br). These bonds are weak due to poor overlap of the bonding orbitals, and these molecules are usually extremely reactive. Hydrogen bonds are also considered weaks bonds as they are in the order of 2-150KJ/mol. Medium strength bonds come in the region of 250-500KJ/mol. Examples of these are C-C, C-O, C-H. A strong bond usually contains multiple bonds between 2 atoms and will have bond energies of over 500KJ/mol. Bonds like N≡N or C=O are good examples of these and are usually extremely hard to break. In Gaussview, the bonds are not always drawn in the structure, but this does not mean that in real life the bonds aren't there. Gaussview draws bonds based on a pre-defined interatomic distance, and so if this distance is great than gaussviews defined max bond length, then a bond will not be drawn. However, in real life, interactions can exist at a great distance than that of the gaussview maximum distance.

All the molecules calculated and discussed above are EX3 triganol planar molecules. All of the exhibit bond angles of roughly 120 degrees, which is what is expected of these compounds. The small deviations from this value were at the 2nd decimal point onwards, and so can be rationalised by low accuracy in the calculations, due to the basis set that was used.

BH3:B3LYP/6-31G(d,p)

Frequency Analysis

| summary data | low modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies - -29.4882 -27.6327 -27.6298 -0.0054 0.1674 0.4015 Low frequencies - 1162.7081 1212.9885 1212.9912 |

Frequency file: here

Vibrational Analysis

| wavenumber | Intensity | IR active? | type |

| 1163 | 92 | yes | bend |

| 1213 | 14 | very slightly | bend |

| 1213 | 14 | very slightly | bend |

| 2583 | 0 | no | stretch |

| 2717 | 126 | yes | stretch |

| 2717 | 126 | yes | stretch |

The IR produced from this calculation only shows 5 peaks, although we would expect there to be 6 vibrational modes for BH3. To calculate the number of modes we use the 3N-6 rule, where N=4 (for BH3), leaving us with 6 modes. However, for a vibrational mode to be IR active, there must be a change in dipole moment. The mode at 2583 is a totally symmetric stretch, resulting in no overall change in dipole, meaning that this mode is not represented on the computed IR spectrum.

GaBr3

Frequency Analysis

| summary data | low modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -1.4878 -0.0015 -0.0002 0.0096 0.6540 0.6540 Low frequencies --- 76.3920 76.3924 99.6767 |

Frequency file: here

Vibrational Analysis

| wavenumber | Intensity | IR active? | type |

| 76 | 3 | extremely slight | bend |

| 76 | 3 | extremely slight | bend |

| 100 | 9 | very slightly | bend |

| 197 | 57 | no | stretch |

| 317 | 57 | yes | stretch |

| 317 | 57 | yes | stretch |

Frequency file: DOI:10042/93039

When wishing to compare data for Optimization and Frequency calculations, you must use the same method and basis set. The basis set used when running a calculation defines the amount of approximations and variables present in the calculation, and so different basis sets give rise to a variance in the accuracy of the results. If one were to use a different basis set for the same molecule, the computed results would differ. This then means that if one were to use a different basis set for two different molecules, the results would be incomparable, due the fact that one calculation would be to a higher degree of accuracy than the other.

When running an optimization calculation, we are looking for the lowest energy geometry of the molecule. An optimisation calculation does this by finding a 0 gradient point on the energy curve. However, we know from simple mathmatics that a 0 gradient point could be a maxima (which corresponds to a transition state) or a minima (which corresponds to the optimized geometry). Therefor, we run a frequency analysis to confirm that our 0 energy point is infact a minima, rather than a maxima/transition state. The "Low frequencies" found in our frequency analysis represent small deviations from our optimized geometry.

BH3 MO Diagram

Energy calculation here

Frequency file: DOI:10042/93186

Copied with permission from Dr. Tricia Hunt's Tutorial problem

Above shows the MO diagram of BH3, with the predicted LCAO's on, besides these are the computed images of the actual MO's present in BH3. The MO's and LCAO's show a range of similarities. If we begin by examining the core MO's, the predicted LCAO's almost exactly match those of the computed MO's. However, as we move up the energy scale, and begin to examine the non occupied LCAO's, the similarities between the LCAOs and MOs become smaller. The MO's begin to become more diffuse and less like the LCAO's. This is probably because as we move up higher in energy, the orbitals begin to deform to remove the unfavourable interactions present in the predicted LCAO's.

NH3

6-31G(d,p) Optimization

optimisation file: DOI:10042/101125

| summary data | convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000006 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000004 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000012 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000008 0.001200 YES |

|

Optimisation log file available here

Frequency Analysis

| summary data | low modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies - -0.0138 -0.0026 -0.0009 7.0783 8.0932 8.0937 Low frequencies - 1089.3840 1693.9368 1693.9368 |

Frequency file: here

Vibrational Analysis

| wavenumber | Intensity | IR active? | type |

| 1089 | 145 | yes | bend |

| 1694 | 14 | very slightly | bend |

| 1694 | 14 | very slightly | bend |

| 3461 | 1 | no | stretch |

| 3590 | ~0 | no | stretch |

| 3590 | ~0 | no | stretch |

Frequency file: DOI:10042/101172

Population Analysis

Population analysis file: DOI:10042/101244 Log of analysis file: here

Here shows the charge distribution of the molecule, red indicating largely negative, and green indicating largely positive. The displayed range is -1.125 to 1.125. The Hyrdrogen atoms are charge with 0.375, and the Nitrogen atom has a charge of -1.125

Association Energy NH3BH3

6-31G(d,p) Optimization

| summary data | convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000233 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000083 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000981 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000370 0.001200 YES |

|

Optimisation log file available here

Frequency Analysis

| summary data | low modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies - -0.0262 -0.0082 -0.0025 9.6693 9.6774 37.9658 Low frequencies - 183.2612 288.4391 288.9493 |

Frequency file: here

Association Energy Calculation

E(NH3)= -56.55776873

E(BH3)= -26.61532352

E(NH3BH3)= -83.22468857

ΔE=E(NH3BH3)-[E(NH3)+E(BH3)]

ΔE= -0.05328224336A.U = -139.89KJ/mol

Ionic Liquid Project

N(CH3)4+

B-31G(d,p) Optimization

optimisation file: DOI:10042/101543

| summary data | convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000012 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000004 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.001226 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000316 0.001200 YES |

|

Optimization log file available here

Frequency Analysis

| summary data | low modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies - -2.1430 -0.0006 0.0010 0.0012 8.2465 10.2880 Low frequencies - 183.2612 288.4391 288.9493 |

Frequency file: here

P(CH3)4+

B-31G(d,p) Optimization

optimisation file: DOI:10042/101545

| summary data | convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000145 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000033 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000693 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000269 0.001200 YES |

|

Optimization log file available here

Frequency Analysis

| summary data | low modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies - -0.0013 0.0019 0.0037 6.9428 9.9472 16.7006 Low frequencies - 157.5732 192.9032 193.1223 |

Frequency file: here

S(CH3)3+

B-31G(d,p) Optimization

optimisation file: DOI:10042/101547

| summary data | convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000045 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000011 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000340 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000131 0.001200 YES |

|

Optimization log file available here

Frequency Analysis

| summary data | low modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies - -8.7013 0.0020 0.0036 0.0046 3.3016 15.4949 Low frequencies - 162.0977 199.2482 199.8336 |

Frequency file: here

Geometry Data

| N(CH3)4+ | P(CH3)4+ | S(CH3)3+ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| r(E-X) | 1.51 | 1.82 | 1.82 |

| θ(X-E-X) | 109.5 | 109.5 | 102.7 |

The geometric data shown above above as 2 key interesting points. The first of these is the fact that optimization showed the E-X bond length for the phosphonium and the sulfonium species were the same. The sulfur atom is a smaller and more electron dense atom than phosphorus, and so you would expect the resulting bond with carbon to be shorter than a C-P bond would, due to the smaller covalent radius present in Sulpher. However, the bonds appear to have the same length. What this means is that in some way the C-P bond must be stronger than the C-S bond.

The phosphonium species that was used in the calculation shows a perfect tetrahedral arrangement, and so it is possible that some extent of pi back donation between the carbon and empty pi* orbitals of the phosphorus, which in turn cause an increase in the bond strength, and so shortens bond length. This affect may also occur in the C-S bond, but because of the distorted geometry of the sulfonium species, the alignment of the orbitals will be worse than the phosphonium species, allowing for less pi back bonding, and so a lesser extent of stabilisation.

The second interesting point the geometric data shows is that of bond angle difference between the 3 species. Both the ammonium and phosphonium species show a bond angle of 109.5, which is characteristic of a tetrahedral complex, however, the sulfonium species has a smaller bond angle of 102.7. All 3 species are "theoretically" of a sp3 hybridisation type, in the sense that there are 4 constituents around the central atom. However, in the case of the sulfonium, one of this, instead of being a methyl group, is a Lone Pair. This one pair on the sulfonium repels the 3 methyl groups attached to the sulfur, and causes them to move slightly close to eachother. This is what causes the reduced bond angle of 102.7, leaving the sulfonium complex with a trigonal pyramidal.

Charge distribution data

Here are the 3 images of the NBO analysis of the above molecules. Green shows positive and red shows negative.

N(CH3)4+ (range -0.483 to 0.483)

P(CH3)4+ (range -1.667 to 1.667)

S(CH3)3+ (range -0.917 to 0.917)

| Heteroatom | Carbon | Hydrogem | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N(CH3)4+ | -0.295 | -0.483 | 0.269 |

| P(CH3)4+ | 1.667 | -1.060 | 0.298 |

| S(CH3)3+ | 0.917 | -0.846 | 0.297 |

The pictures above represent the charge distribution in our optimized molecules. As can be seen from the images and table, the phosphonium and sulfonium species show a fairly similar charge distribution. Both phosphorus and sulfur are less electronegative atoms than carbon, and so this rationalises the fact that in these molecules are positively charged, and the carbon is negative. The reason that we see a greater range of charge distribution in the phosphonium molecule is because the electronegativity difference between carbon and phosphorus is greater than that of carbon and sulfur. However, we see an interesting result in the charge distribution of the ammonium molecule. Here we see that infact the nitrogen atom is negatively charged, as well as the carbon, however the carbon is less negative than it is in the other 2 molecules. Contrary to the other 2 molecules, the heteroatom here (nitrogen) is actually more electronegative than carbon, and this is why we see the negative charge on nitrogen. In all 3 molecules the charge on the surrounding hydrogen atoms is positive, and the slight deviates are there due to the other atoms (carbon+heteroatoms) electronegative forces. This last fact is of interest because usually we depict an [NR4]+ ion as having the positive charge localised to the nitrogen atom, however the results above actually show that the nitrogen atom is infact negatively charged. The formal + next to a nitrogen atom traditionally represents a charge of +1 on that atom, but our data contradicts that fact. There is however some semblance in the placing of the + next to the nitrogen, as it is "less negative" than the surrounding carbons. However, in actual fact, in this ammonium molecule, all the actual positive charge is harboured on the surround Hydrogen atoms.

N(CH3)4+ MO analysis

6th MO

This MO shows strongly bonding interactions all throughout the molecule. There is one large interaction that occurs all throughout the molecule. As this is all in one phase, all interactions are strongly bonding interactions. This MO is delocalised across the whole molecule. This MO is totally symmetric and so is completely bonding.

7th MO

This MO consists of 2 large orbitals that are out of phase with eachother. Each orbital covers 2 methyl groups, and within this orbital there are strong bonding interactions between the 2 methyl groups. However, because the 2 orbitals are out of phase with each other, there is a nodal plane that runs down the center of the molecule. Overall this MO is a bonding orbital, but there are small contributions of antibonding character due to the nodal plane and the antibonding interaction between the 2 hemispheres of the MO.

10th MO

This MO shows a weakly bonding orbital. Each methyl group is covered by a same phase hemisphere and the central atom is in out of phase sphere. There are nodal planes between the methyl groups and and the central atom, and this causes antibonding character. However, there are strong through space interactions between the methyl groups, which adds to the bonding character.

15th MO

This MO is an antibonding orbital. There are 4 symmetrical parts of this MO, each alternating around the central atom. There are 2 nodal planes in this MO that effectively cut it into quarters. There are therefor strong antibonding interactions between any given MO, and its 2 opposing phase neighbours. There are however some through space interactions that occur diagonally across the molecule between the MO's that in in phase with eachother. This adds a small amount of bonding character to the molecule, but not enough to cancel out all the antibonding interactions.

18th MO

This MO is very similar to the one above, but simply more extreme. This MO has alternating in phase and out of phase MO's that all have strong antibonding interactions and a nodal plane between them. There is a small amount of through space interactions between the same phase MO's like above, but the great extent of alternating phase in this MO causes it to be a strongly antibonding MO.

N(CH3)3(CH2OH)+

B-31G(d,p) Optimization

optimisation file: DOI:10042/109526

| summary data | convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000013 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000004 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000293 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000090 0.001200 YES |

|

Optimization log file available here

Frequency Analysis

| summary data | low modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies - -121.6758 -2.1038 -0.0005 0.0005 0.0005 4.7587 Low frequencies - 5.7932 129.7443 217.5849 |

Frequency file: here

The frequency calculations performed here yielded one anomalous result. One of the low frequencies that was obtained as -121.6758 which is well outside the range of what we would expect. This large negative frequency is a result of gaussviews approximations causing errors. When the molecules was built, the OH group is formed by turning an H into an OH group. This causes gaussview to not realise what the bond of the OH actually is, meaning the optimization and frequency is wrong, causing an abnormal frequency.

N(CH3)3(CHCN)+

B-31G(d,p) Optimization

optimisation file: DOI:10042/109541

| summary data | convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000033 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000008 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.001554 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000307 0.001200 YES |

|

Optimization log file available here

Frequency Analysis

| summary data | low modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies - -3.4440 -0.0007 -0.0006 -0.0004 6.6757 9.2464 Low frequencies - 91.6981 153.9740 210.6354 |

Frequency file: here