Rep:Mod:md308

Mark Driver

Module 1

Introduction

Molecular modelling is often used in organic chemistry to study the structure and reactivity of chemical systems. Molecular models can be used to rationalise the outcomes of many reactions as well as predicting novel reaction pathways.

In this study molecular mechanics is used to predict the stereochemical outcomes of:

- The hydrogenation of cyclopentadiene dimer.

- The nucleophilic addition to pyridinium rings.

- The conformation/atropisomerism of a large ring ketone intermediate in one synthesis of Taxol.

And semi-empirical and DFT molecular orbital theory is used to study:

- The origins of regioselectivity in the electrophilic carbenylation of a substituted bicyclic diene.

- Neighbouring group participation (NGP) on the C-Cl and/or C=C stretching frequency of the same bicyclic diene.

The project will conclude with a spectroscopic simulation of an organic molecule.

Molecular Mechanics Modelling

Molecular mechanics is a molecular modelling technique which optimises the molecular structure by adjusting the geometry to reach an energy minimum. ChemBio3D Ultra incorporates Allinger's[1] MM2 force field which is used to carry out this optimisation. The results of this analysis can be used to determine regio- and stereoselectivity and explain reaction mechanisms.

Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

Dimerisation of Cyclopentadiene

Cyclopentadiene readily undergoes dimerisation via a Diels-Alder reaction to form a diene[2] which can then be hydrogenated to give saturated compounds. The regio- and stereochemistry of these reactions are conveniently studied by molecular mechanics. The thermodynamic stability of these compounds can be determined from the results of these calculations.

There are two potential isomers which could be formed during the dimerisation. However, Wilson et al[2] demonstrated that the endo product 2 is selectively formed over the exo product 1, with the exo only being formed at higher temperatures.[3] The table below summarises the results of the molecular mechanics analysis for the two dimers.

| Dimer |

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Stretch / kJ mol-1 | 5.4 | 5.3 |

| Bend / kJ mol-1 | 86.14 | 87.36 |

| Stretch-Bend / kJ mol-1 | -3.5 | -3.5 |

| Torsion / kJ mol-1 | 32.1 | 39.8 |

| Non-1,4 VDW / kJ mol-1 | -5.9 | -6.4 |

| 1,4 VDW / kJ mol-1 | 17.7 | 18.0 |

| Dipole/Dipole / kJ mol-1 | 1.6 | 1.9 |

| Total Energy / kJ mol-1 | 133.5 | 142.4 |

The table above indicates that the exo dimer 1 is thermodynamically more favourable as it has a total energy 8.9 kJ mol-1 lower than the endo product 2. From the table it is clear that the majority of this difference comes from a difference in torsion strain. This reflects the rigidity of the molecules. However, the dimerisation produces exclusively the endo product 2. This suggests that the reaction is under kinetic rather than thermodynamic control. The transition state which leads to the endo dimer is of lower energy than that which leads to the exo dimer. This is due to a favourable secondary orbital interactions between the HOMO of one cylcopentadiene with the LUMO of the other, this increases the attractive interactions between the molecules and stabilises the endo transition state. This interaction is only present in the endo transition state so this is stabilised relative to the exo transition state.[4] The Diels-Alder reaction is irreversible[5] so the fastest reaction will dominate leading to the observed selectivity for the endo dimer 2 at low temperature. At High temperature the energy barrier is overcome and the exo dimer can be formed. The observation of endo selectivity is also in keeping with the Woodman Hoffman rules[6] which also favour the endo product.

Hydrogenation of Cylopentadiene Dimer

The cyclopentadiene dimer can undergo hydrogenation to give initially a dihydro derivative and after a prelonged period the saturated tetrahydro derivative.

Molecular mechanics calculations can be used to analyse the dihydro derivatives 3 and 4 to determine the thermodynamic stability of the hydrogenated products.

|

|

|

| |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stretch / kJ mol-1 | 5.2 | 4.6 | 4.6 |

| Bend / kJ mol-1 | 79.3 | 60.7 | 53.9 |

| Stretch-Bend / kJ mol-1 | -3.2 | -2.3 | -2.0 |

| Torsion / kJ mol-1 | 50.7 | 52.3 | 71.1 |

| Non-1,4 VDW / kJ mol-1 | -6.4 | -4.4 | -5.7 |

| 1,4 VDW / kJ mol-1 | 23.9 | 18.8 | 25.5 |

| Dipole/Dipole / kJ mol-1 | 0.7 | 0.6 | N/A |

| Total Energy / kJ mol-1 | 150.2 | 130.4 | 147.5 |

Molecular mechanics calculations show that the dihydro derivative 4 is the thermodynamically most favourable product of the hydrogenation of 2. The dihydro derivative 3 is 19.8 kJ mol-1 higher in energy than 4, this energy difference mostly comes from the bending contribution. This suggests that the relatively high energy of 3 is caused by a higher level of steric crowding. This repulsive interaction destabilises the molecule. Interestingly, even the tetrahydro derivative 5 has lower energy than 3, indicating that the prescence of the norbornene alkene in these molecules leads to unfavourable interactions.

The selectivity for 4 over 3 can also be rationalised by considering the alkenes in dimer 2. These are clearly in very different environments, one cyclopentene and a norbornene. The bridging methylene group gives rise to increased strain at the norbornene alkene, this results in higher bond lengths and strained bond angles. This makes the norbonene less stable and hence more reactive than the cyclopentene group. Hydrogenation at this position relieves this strain so stabilises the molecule.

It has been shown[7] that the sole product of hydrogenation is the dihyrdo derivative 4. This equates well with the molecular mechanics calculations and suggests that the hydrogenation is under thermodynamic control

Nucleophilic Addition to Pyridinium Rings

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) is an important chemical found in living cells. It is of interest as it pays key roles in many biological processes including metabolism and posttranslational modifications. In this section two analogues of NAD+ will be used to study nucleophilic addition to the 4 position of the pyridinium rings. In the first reaction an optically active derivative of prolinol 6 undergoes stereoselective methylation of the pyridinium to give the pyridoxazepinone7 with the absolute stereochemistry shown below. The second reaction involves stereoselective amination of an azepino quinolinium 8 to give the aniline derivative 9.

| |

It has been shown that the stereochemical outcome of this reaction is determined by the conformation of the 7-membered ring and in particular the orientation of the carbonyl group.[8] In order to investigate further, molecular mechanics modelling was used to determine the optimal geometry of 6. This was done using the MM2 force field in ChemBio 3D Ultra to minimise the total energy. Particular attention was paid to the dihedral angle between the carbonyl and the pyridinium ring. It was found that the most stable conformation placed the carbonyl at an angle of 10.4° above the pyridinium ring (see graph). The observed stereochemistry of the methylated product can be explained by chelation between the carbonyl and the Gringard reagent. Favourable interactions between the carbonyl and the Magnesium ion lead to the methyl group approaching selectively from the top face of the pyridinium. If the pyridinium and carbonyl were coplanar then we would expect to observe a 50:50 distribution of the two isomers as there would be equal probability of attack from the top or bottom face. Chelation control from the carbonyl guides the methyl group to attack the top face of the pyridinium. This also accounts for the regioselectivity observed in the product as the 4 position is ideally positioned for attack from a coordinated grignard. Ideally the transition state geometry would be optimised to fully rationalise the stereochemical outcome. However, It is difficult to handle Mg with this optimisation method. The Grignard could be incorporated if a different technique was used such as MOPAC PM6 molecular orbital method. However, This would have required more computational time to optimise the geometry and the MM2 calculation on 6 was sufficient to rationalise the stereochemical outcome.

The second reaction involves stereoselective amination of a quinolinium compound 8.[9] The selectivity is not restricted to amine nucleophiles; similar results were observed with other nucleophillic reagents including hydrides, enolates and cyanides.[10] [11]

| |

|

|

|

A similar approach was used to optimise the geometry of the azepino quinolinium 8, this allows for rationalisation of the stereoselectivity of these reactions. The stereochemistry of these reactions is again determined by the carbonyl group. In this case it is due to steric repulsion blocking attack from one face of the pyridinium.[9] MM2 Optimisation was carried out to find the geometry with minimum energy. This suggests that carbonyl is angled at 19.6° below the plane of the aromatic ring system. This is in agreement with the idea of steric control of stereochemistry. The carbonyl blocks the bulky aniline attacking on the bottom face of the quinolinium ring; the nucleophile can therefore only approach over the top face leading to the observed stereochemistry in the product.

Conformational Analysis of a Large Ring Ketone

One key intermediate in the total synthesis of Paclitaxel (Taxol)[12] is an atropisomeric large ring ketone. Transannular interactions hinder rotation so two distinct atropisomeric forms can be observed; the carbonyl can be pointing either "up" 10 (as shown in the image on the right) or "down" 11. The optimal geometry of each atropisomer was determined using the MM2 force field.

| Atropisomer |

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Stretch / kJ mol-1 | 9.74 | 9.75 |

| Bend / kJ mol-1 | 58.76 | 55.26 |

| Stretch-Bend / kJ mol-1 | 1.17 | 0.82 |

| Torsion / kJ mol-1 | 87.60 | 77.26 |

| Non-1,4 VDW / kJ mol-1 | -9.34 | -5.81 |

| 1,4 VDW / kJ mol-1 | 54.73 | 53.19 |

| Dipole/Dipole / kJ mol-1 | 0.03 | -0.24 |

| Total Energy / kJ mol-1 | 202.70 | 190.23 |

It was found that the most stable conformation for both atropisomers was with the cyclohexyl ring in a chair conformation. Both atropisomers showed a strained alkene with significant deviation from planarity and bond angles of around 125°. This pyramidalisation suggests a degree of sp3 character in the alkene. From the table above it is clear that 10 is the most stable atropisomer as it has a total energy 12.5 kJ mol-1 lower than 11. This difference is mostly accounted for by the difference in torsional energy. This result can be rationalised by considering the steric clash between the bulky bridging group and the carbonyl. The up isomer is destabilised by this interaction whereas the down isomer is not. The down isomer is therefore the most stable form of the intermediate. The MMFF94 forcefield produced significantly higher energies but confirmed the same trends as observed with the MM2 force field.

Both isomers show remarkable stability and addition to the alkene is unusually slow. Hyperstable alkenes such as these are resistant to addition due to very low strain at the alkene position.[13]. Bridgehead alkenes are usually very strained, in large ring systems however this strain can be relieved to the point where it is actually favourable to have a bridgehead alkene.[14] The alkene strain can be calculated as the energy difference between the saturated parent hydrocarbon and the alkene where both compounds are in their most stable conformation.[13] Alkene strain is usually positive, due to the high strain at bridgehead alkenes, however in hyperstable alkenes it is negative giving rise to the unusual stability of these compounds.

Molecular Modelling Using Semi-Empirical Molecular Orbital Theory

The MM2 force field is limited because it is a purely mechanical calculation, it cannot take into account electronic contributions. In this section I will use the MOPAC PM6 method to approximate the molecular wavefunction of the valence orbitals. This will allow for analysis of the electronic aspects of the bonding, reactivity and spectroscopic properties of organic molecules. Vibrational spectra can then be calculated using the density functional approach.

Regioselective Addition of Dichlorocarbene

Reactivity

9-chloro-1,4,5,8-tetrahydro-4a,8a-methanonaphthalene 12 undergoes regioselective addition with dichlorocarbene to form the syn trichloride 13 and the diadduct 14 exclusively (72:23).[15] [16] The anti adduct is not observed. Semi-empirical calculations will be used to demonstrate orbital control in this reaction.

| ||

The geometry of 12 was optimised using the MM2 force field giving a minimum energy of 74.88 kJ mol-1. MOPAC PM6 was then used to optimise the geometry further taking into account electronic contributions this gave the heat of formation as 82.59 kJ mol-1. The molecule has Cs symmetry so it has a plane of symmetry bisecting the molecule, the molecular orbitals generated from this calculation were found to be unrealistic as they did not display this plane of symmetry, This is a known bug in the program. I experimented with other calculation methods and found that the MOPAC RM1 method gave symmetrical orbitals. This however produced a geometry which had a heat of formation as 95.51 kJ mol-1, the varational theorem would suggest that PM6 is a better method as the energy associated with the optimised geometry is lower. Due to the more realistic molecular orbitals produced, the results below are based on the RM1 method.

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

The HOMO is the syn alkene π orbital, therefore the syn alkene will be more nucleophilic than the anti alkene (HOMO -1). The high electron density at relatively high energies means that the syn alkene will be attacked by electrophiles before the anti alkene. Donation from the anti π orbital into the C-Cl σ* orbital stabilises the anti alkene and makes it less nucleophillic relative to the syn alkene. The manifestations of this interaction can be seen in the geometry of these bonds. The syn alkene is longer than the anti alkene, and it has slightly wider bond angles and trans-dihedral angles deviate from 180°. The endo selectivity can be rationalise as being due to the steric bulk of the chlorocycplopropane group on the exo face. The endo face is sterically unhindered so is more easily attacked by electrophiles.

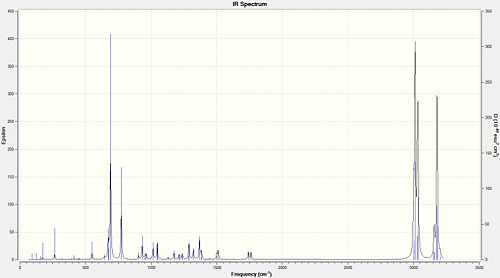

Vibration Frequencies

I will now calculate the vibrational frequencies of this molecule 12 and the hydrogenated version 13 using a density functional approach. The geometry of both molecules was optimised using MM2 followed by MOPAC/RM1 calculations. The molecules were then subjected to B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) Gaussian geometry optimisation and vibrational frequency calculations [17][18].

|

|

| Stretching frequency / cm-1 | ||

| syn-C=C | 1760.95 | 1761.71 |

| anti-C=C | 1740.95 | N/A |

| C-Cl | 772.62 | 776.76 |

The calculated vibrational frequencies tabulated above are in broad agreement with the expected values for these functional groups. The alkene stretches are a little high but this is most likely due to errors in the calculation method used. These would most likely be improved by using a larger basis set or by giving a full quantum mechanical treatment to these molecules. However, this would would vastly increase the complexity of the calculations and therefore require far more computational power and time.

The vibrational frequencies of these molecules provides further evidence for the existence of the HOMO-1/LUMO interaction described above. The donation of electron density from the anti π orbital into the C-Cl σ* orbital weakens the C-Cl bond. The anti alkene has been removed in 13 so this interaction is no longer possible. This leads to a 4.14 cm-1 increase in the stretching vibration of the C-Cl bond. The removal of the anti alkene has had little effect on the syn alkene, a small increase is observed possibly due to relief of strain imposed on it by the rigid conformation of 12.

Structure Based Mini Project Using DFT-based Molecular Orbital Methods

Introduction

Cycloaddition reactions can give a number of different regio- and stereoisomers. (4+3) Cycloadditions are a particularly useful synthetic method for making 7 membered ring systems.[19] [20] This involves a cycloaddition between a diene and an oxy-allyl cations. Much work has been carried out in developing methods of generating the oxy allyl cation under chemoselectively and under mild conditions, this technique has been used in the synthesis of several complex natural products.[21] [22] Recently, Lo and Chiu reported[23] a series of (4+3) cycloadditions of epoxy enol silanes which exhibit facial selectivity and stereospecificity. I will use DFT-based molecular orbital methods to investigate the selectivity of this reaction. The assigned regio- and stereochemistry will be confirmed by semi-empirical molecular orbital methods where the spectroscopic properties of these molecules will be approximated. During the course of this analysis I will concentrate on one particular reaction which showed a particularly high level of selectivity. This a (4+3) cycloaddition reaction between a triethyl silyl epoxy enol ether 14 and spiro[2.4]hepta-4,6-diene 15 to form (hydroxmethyl)spiro[bicyclo[3.2.1]oct[6]ene-8,1'-cyclopropan]-3-one 16-19 (Referred to by Lo and Chiu as 1a, 4b and 2f respectively)

Mechanism and selectivity

Of the 4 potential products of this reaction, it was reported that only 16 and 17 were formed in a ratio of 77:23[23]. These are regioisomers formed from attack on the same face of the alkene. Lo and Chiu[23] suggest that this facial selectivity is imposed on the system by the bulky silyl substituents. These block one face of the alkene from attack, giving rise to the observed facial selectivity leading to 16 and 17 as the exclusive products of the reaction. The proposed mechanism[23] of the reaction below demonstrates that the stereochemistry of the product is determined by the regiochemistry.

As discussed above the silyl group is restricted to approaching the diene with a syn relationship between the diene and the oxygen. This is due to steric repulsion between the cyclopropyl group and the silyl groups. This limits the products to either 16 or 17 depending on the regiochemistry of the alkene. The stereochemistry is determined by the orientation of the epoxide; where the epoxide is pointing up this opens to give product 16. However, if the epoxide is pointing down this leads to product 17. The reaction begins with activation of the epoxide with a silyl triflate the activated epoxyenol then undergoes the (4+3) cycloaddition with ring opening of the epoxide to give a silyl ether. Results obtained by Lo and Chiu indicate that the transition state of the cyclo addition is reactant-like and has epoxide and alkene character. This early transition state gives rise to the observed stereospecificity. A late transition state where the cycloaddition followed epoxide ring opening rather than preceeding it could potentially lead to products 18 and 19 via rotation about the "epoxide" C-C bond. The silylketone intermediate dissociates to give a ketone and regenerate a silyl triflate which can then activate further epoxides. The catalytic activity of the silyl triflate is low, 10 mol% is typically required. The primary silyl ether is then converted back to an alcohol by work-up with triethylamine trihydrofluoride.

To explain the selectivity observed in this reaction we need to determine whether the reaction is under themodynamic or kinetic control (or both). Given the symmetrical nature of the diene there is no electronic reason to favour one isomer over the other as the MO's will also be symmetrical. MM2 geometry optimisations give energies of 100.06 kJ mol-1 and 89.01 kJ mol-1 for 16 and 17 respectively. This suggests that the latter is the thermodynamically most stable species. The reaction conditions (-91 °C, 1hr) appear to be designed so as to place the reaction under kinetic rather than thermodynamic control. Therefore the species which forms via the lowest energy transition state will be formed preferentially. This implies that given the regioselectivity reported for this reaction the transition state leading to 16 is of lower energy than that which leads to 17. These assertions make intuitive sense. Space filling models of the silyl derivatives formed from the cycloaddition can be used as an approximation of the transition state. They are structurally similar to the conformation required in the transition state although less rigid due to the opened epoxide ring. As discussed already the steric bulk provided by the silyl groups dominates the reactivity of this system. It is plausible that the same forces are at work here. MM2 geometry optimisation gives the energy of the transition state analogues 16' and 17' as 122.61 kJ mol-1 and 170.80 kJ mol-1 respectively. The reason for this large difference can be seen in spacefilling models of these molecules. In 16' there is steric repulsuion between the silyl groups and the cyclopropane group. In 17' there is a similar interaction between the silyl groups and the bridging alkene. The latter of these interactions is more destabilising as the cyclopropane group points away from the silyl groups whereas the alkene does not. These effects are likely exacerbated in the true transition state as they are less flexible and less able to adjust the conformation to avoid these repulsive interactions. This accounts for the observed regioselectivity. Lo and Chiu[23] found that by varying the substituents on the reactants it is possible to tune the products selectivity, although very hindered reactants led to low yields.

Characterisation

Now that the selectivity of the products have been rationalised, the only remaining task is to verify the structures assigned in the literature. This can be done by calculating various physical and spectroscopic properties and comparing to that reported in the literature. Although, an extensive literature search has been carried out spectroscopic data other than that reported by Lo and Chiu[23] is not available. Therefore, this will be used for comparison to the computed results. The physical and spectroscopic properties which may be useful for characterisation are optical rotation, vibrational spectra and 13C NMR spectra. 1H NMR spectra could be estimated but due to the similarity between the molecules would be unhelpful in distinguishing between the isomers. Unfortunately, optical rotation data is not reported. Therefore, I will concentrate on calculating the IR and 13C NMR data. The reported data for these compounds is summarised below[23].

Molecule 16

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 214.0,137.2, 134.8, 62.7, 57.9, 48.7, 45.8, 45.5, 36.5, 13.7, 7.7 ppm;

IR (CHCl3) 3546 (OH), 1067, 3022, 2938, 2884, 1690 (C=O), 1410, 1348 cm-1

Molecule 17

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 214.4, 137.3, 136.9,62.8, 58.1, 46.8, 45.1, 44.4, 32.2, 11.2, 7.9 ppm;

IR (CHCl3) 3524 (OH), 3065, 3022,3017, 3012, 2938, 2890, 1690 (C=O), 1407, 1347 cm-1

Vibrational Frequency Calculations

The vibrational frequencies were calculated by using B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) Gaussian geometry optimisation and vibrational frequency calculations.

|

|

| Vibration | 16 / cm-1[24] | 17 / cm-1[25] |

|---|---|---|

| O-H Stretch | 3639.65 | 3670.40 |

| C=O Stretch | 1768.34 | 1779.42 |

| C=C Stretch | 1680.74 | 1671.36 |

| O-H Bend | 1479.06 | 1469.63 |

| C-O Stretch | 1086.73 | 1095.36 |

The table above displays the key vibrations of the functional groups present in the two compounds of interest. Many of the calculated frequencies are at significantly higher wavenumbers than those reported in the literature. This is possibly due to errors inherent in the calculation methods, such as the way these calculations handle solvents. This makes direct comparisons difficult, although some general observations can be made. For example, The OH and C=C stretching modes are at lower energy in 16 than 17. These trends are in agreement with those reported in the literature. Comparisons between the calculated vibrational frequencies and those reported in the literature have proved inconclusive.

13C NMR Chemical Shift Calculations

13C NMR chemical shifts were calculated using the GIAO approach to quantum mechanical density functional theory, and the mpw1pw91 method with 6-31g basis set.

The results of this calculation are tabulated below.

| Calculated Chemical Shifts / ppm | Literature Chemical Shifts / ppm | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecule 16[26] | Molecule 17[27] | Molecule 16 | Molecule 17 | |

| C1 | 36.4 | 39.5 | 32.2 | 36.5 |

| C2 | 50.7 | 50.5 | 46.8 | 48.7 |

| C3 | 58.7 | 57.6 | 58.1 | 57.9 |

| C4 | 218.4 | 214.8 | 214.4 | 214.0 |

| C5 | 46.0 | 46.3 | 44.4 | 45.5 |

| C6 | 47.6 | 47.8 | 45.1 | 45.8 |

| C7 | 11.1 | 10.2 | 7.9 | 7.7 |

| C8 | 15.4 | 16 | 11.2 | 13.7 |

| C9 | 137.8 | 136.8 | 137.3 | 137.2 |

| C10 | 136.5 | 133.9 | 136.9 | 134.8 |

| C11 | 65.4 | 63.5 | 62.8 | 62.7 |

The calculated results are in reasonably good agreement those reported in the literature. The calculations reproduce the experimental result with a mean error of 2.45 ppm and a maximum error of 4.2 ppm for 16; and with a mean error of 1.13 ppm and a maximum error of 2.5 ppm in the case of 17. Interestingly, a better fit can be achieved by swapping the assignments for the reported data. The calculated values of 16 compared to the experimental values of 17 have a mean error of 1.77 ppm with a maximum error of 4.4 ppm. When the calculated values of 17 are compared to 16 this gives a mean error of 1.80 ppm and a maximum error of 7.3 ppm. This raises the possibility that the authors have incorrectly assigned the structures of the products. These results are far from conclusive as it is still possible that the discrepancy is due to errors inherent in the calculation. More detailed calculations with larger basis sets or more complex calculation methods are needed to further investigate. Other experimental data would also be useful in order to test the reproducability of the experiment. If this were to be proven correct then it would require a reanalysis of the origin of the observed regio- and stereochemistry.

References

- ↑ N.L.J. Allinger, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1977, 99, 8127: DOI:10.1021/ja00467a001

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 P.J. Jr. Wilson, J.H. Wells, Chem. Rev., 1944, 34, 1: DOI:10.1021/cr60107a001

- ↑ J.E. Baldwin, Journal of Organic Chemistry 1966, 31, 2441–2444 DOI:10.1021/jo01346a003

- ↑ J. Clayden, N. Greeves, S. Warren and P. Worthers in Organic Chemistry Oxford University Press, 2001, p.916

- ↑ J. Sauer, R. Sustmann, Angew. Chem, 1980, 19, 779: DOI:10.1002/anie.198007791

- ↑ R. Hoffmann, R.B. Woodward, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1965, 87, 4388: DOI:10.1021/ja00947a033

- ↑ D. Skála, J. Hanika, Pet. Coal, 2003, 45, 105: PDF

- ↑ A. G. Shultz, L. Flood and J. P. Springer, J. Org. Chemistry, 1986, 51, 838. DOI:10.1021/jo00356a016

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 S. Leleu, C. Papamicael, F. Marsais, G. Dupas, V. Levacher, Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, 2004, 15, 3919-3928. DOI:10.1016/j.tetasy.2004.11.004 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Azepinoquinolinium 1" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ K. Ichinose, M. Kodera, J. Leeper, R. Battersby, J.Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1999, 8, 879DOI:10.1039/a809858a

- ↑ S. H. Mashraqui, R.M. Kellogg, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983,105, 7792.DOI:10.1021/ja00364a079

- ↑ K.C. Nicolaou, P.G. Nantermet, H. Ueno, R.K. Guy, E.A. Couladouros, E.J. Sorensen, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1995, 117, 624: DOI:10.1021/ja00107a006

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 W.F. Maier and P.V.R. Schleyer J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981, 103, 1891–1900 DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "hyperstable alkene 1" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ A.B. McEwen and P.V.R. Schleyer J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 3951–3960.DOI:10.1021/ja00274a016

- ↑ B. Halton, S. G. G. Russell. J. Org. Chem., 1991, 56, 19, 5553–5556 DOI:10.1021/jo00019a015

- ↑ B. Halton, R. Boese and H. S. Rzepa., J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 2, 1992, 4 447. DOI:10.1039/P29920000447

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-7412

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-7413

- ↑ M. Harmata Chem. Commun., 2010, 46, 8886-8903DOI:10.1039/C0CC03620J 10.1039/C0CC03620J

- ↑ M. Harmata Chem. Commun., 2010, 46, 8904-8922 DOI:10.1039/C0CC03621H

- ↑ J. E. Antoline, R. P. Hsung, J. Huang, Z. Song, and G. L. Org. Lett., 2007, 9, 7, 1275–1278 DOI:10.1021/ol070103n

- ↑ M. V. Pascual, S. Proemmel, W. Beil, R. Wartchow, and H. M. R. Hoffmann Org. Lett., 2004, 6, 23, 4155–4158 DOI:10.1021/ol048603t

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 23.6 23.7 B. Lo, P. Chiu Org. Lett., 2011, 13, 5, 864–867 DOI:10.1021/ol102897d Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "mini project" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-7414

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-7415

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-7420

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-7421