Rep:Mod:mcpdpart1

The hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

Introduction

*The aims of this computational exercise are to rationalise the formation of the endo dimer by inspecting the energies of both possible dimerisation outcomes and to determine whether the hydrogenation step is kinetically or thermodynamically controlled.

Energy calculations

The energies of the four compounds were computed via molecular mechanics techniques using both the Avogadro and ChemBio3D software.

Each of the structures was drawn in ChemBio3D and optimized using both the MM2 and MMFF94s force fields. The results of the MM2 force field computations for the total energies are summarized in the table below.

| Compound | Total bond stretching energy | Total angle bending energy | Total torsional energy | Total van der Waals energy | Total electrostatic energy | Total energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISOMER 1 | 1.2850 | 20.5806 | 7.6554 | 2.816 | 0.3775 | 31.8764 |

| ISOMER 2 | 1.2509 | 20.8476 | 9.5110 | 2.7762 | 0.4476 | 33.9975 |

| ISOMER 3 | 1.2348 | 18.9383 | 12.1239 | 4.2274 | 0.1631 | 35.9266 |

| ISOMER 4 | 1.0965 | 14.5242 | 12.4974 | 3.4427 | 0.1406 | 31.1520 |

The optimized geometries obtained in ChemBio3D were exported as .cml files and opened in Avogadro, where MMFF94s force field optimizations were performed for each compound. The results are shown below.

| Compound | Total bond stretching energy | Total angle bending energy | Total torsional energy | Total van der Waals energy | Total electrostatic energy | Total energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISOMER 1 | 3.54307 | 30.77307 | -2.73335 | 12.80342 | 13.01370 | 55.37349 |

| ISOMER 2 | 3.47132 | 33.17112 | -2.97214 | 12.38562 | 14.21187 | 58.20615 |

| ISOMER 3 | 3.31132 | 31.93650 | -1.47005 | 13.63738 | 5.11951 | 50.44567 |

| ISOMER 4 | 2.82536 | 24.68664 | -0.39107 | 10.65026 | 5.14689 | 41.25949 |

Notes:

- The calculated energies have units of kcal mol-1.

- The MM2 and MMFF94s are different models, therefore the energies obtained within each method should not be compared. However, it is possible to compare the energies within each table.

- As expected, the MMFF94s force field optimization produced the same total energy in both ChemBio3D and Avogadro.

Discussion

Both optimization fields produce the same qualitative result in the sense that they both reveal a higher energy for the 1&2 pair compared to the hydrogenated versions 4&5. It therefore follows that the hydrogenation process leads to compounds which are more stable than the starting dimer.

The energy of the endo form is higher than for the exo one, which makes it less stable. However, bearing in mind that the endo isomer is selectively produced, it results that the reaction is under kinetic control (and follows the endo rule). Even though the endo product is higher in energy, the transition state leading to it is lower in energy than the transition state leading to the exo adduct, thus it is accessed faster and leads to the kinetic product. The calculated energies therefore confirm the theoretical knowledge that the least stable dimer is formed under kinetic control.

The exo dimer is more stable than the endo version mainly due to its lower torsional strain as highlighted by the computed values. The angle bending energy is also lower for the exo form, confirming the better obey to the ideal bond angles in exo c.f. endo.

Upon hydrogenation, one of the isomers 3 or 4 is formed rather than the completely hydrogenated version. The energy of the tetrahydro derivative was found to be 35.2743 kcal mol-1 (MM2 minimization)/38.019 kcal mol-1(MMFF94s minimization), thus lower than the energies of the corresponding dihydro dimers. Since this low energy state is only achieved after prolonged hydrogenation, it follows that the hydrogenation reaction is also kinetically controlled, with lower transition state energies towards the dihydro derivatives.

It is easier to hydrogenate the double bond in the bridged cycle than the one in the unbridged cycle, as can be seen from the lower energy of isomer 4 compared to isomer 3. This effect is produced by the higher torsional energy in 3, which is a consequence of having a double bond "trapped" into a bridged structure. It is therefore expected that the dihydro product formed first will be 4.

Atropisomerism is a type of stereoisomerism whereby chirality arises due to restricted rotation about a single bond (thus no stereogenic center). Therefore there is a barrier of rotation and the isomers can be isolated.

The aim of this computational exercise is to determine which intermediate (9 or 10) from the synthesis of Taxol proposed by Paquette [2] is more stable. In these structures, rigidity arises due to the bridge structure, fused rings and carbonyl group, leading to atropisomerism. The stereochemistry of the carbonyl addition depends on the stability of the isomers.

| Compound | Total bond stretching energy | Total angle bending energy | Total torsional energy | Total van der Waals energy | Total electrostatic energy | Total energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISOMER 9 | 2.7847 | 16.5412 | 18.2513 | 11.5567 | -1.7248 | 47.8395 |

| ISOMER 10 | 2.6205 | 11.3393 | 19.6719 | 10.7152 | -2.0023 | 42.6828 |

The molecules were drawn in ChemBio3D and optimized by setting the 6 membered rings into a chair conformations and minimizing the strain around the double bond. MM2 force field optimizations were subsequently performed, leading to the energy values listed in this section's table.

By inspecting the calculated energies it follows that isomer 10 ("down") is more stable than isomer 9 (by about 5 kcal mol-1). In fact, even the initial optimization of structure 9 in ChemBio3D converted the structure into isomer 10, already suggesting the preferred configuration. The important contribution in this sense is that of angle bending strain, which is much higher for the "up" isomer.

In spite of the higher stability of isomer 10, isomer 9 was still obtained in the reported synthesis. This can be rationalized in terms of the nature of the transition state involved in the Cope rearrangement that occurs, which is endo for kinetic reasons.[2]

Spectroscopic Simulation using Quantum Mechanics

Molecule 18, which is a derivative of compound 10, was subjected to a spectroscopic simulation to predict the 13C NMR and 1H NMR chemical shifts.

Procedure

The structure was drawn into ChemBio3D and subjected to multiple MM2 force field optimization following various adjustments in the position of the atoms to minimize repulsions. After finding a low enough energy value (64.2207 kcal mol-1), the file was saved in a .cml format and opened in Avogadro. A MMFF94s force field minimization was performed. From the Extensions/Gaussian menu, the following parameters were implemented:

- Geometry optimisation (Opt + Freq)

- Theory: B3LYP

- Basis set: 6-31G(d,p)

- Solvation mode: CPCM, Chloroform

- Keywords: Freq NMR, Empirical Dispersion = GD3

The generated input file was submitted to the HPC system. When the job was indicated as finished, the formatted checkpoint file was downloaded and opened in Gaussview. The NMR spectra were accessed from Results/NMR, paying attention to select the corresponding basis set, the TMS reference and the benzene solvent. The .txt files containing the chemical shifts were used for comparison with the literature. The spectra were also exported as .svg files. DOI:10042/25746

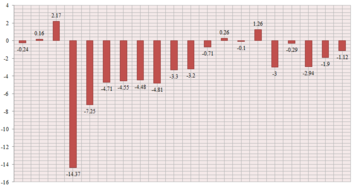

13C NMR

| δ Predicted (ppm) | δ Literature [3] (ppm) | Difference (ppm) |

|---|---|---|

| 211.73 | 211.49 | -0.24 |

| 148.56 | 148.72 | 0.16 |

| 118.73 | 120.9 | 2.17 |

| 88.98 | 74.61 | -14.37 |

| 67.78 | 60.53 | -7.25 |

| 56.01 | 51.30 | -4.71 |

| 55.49 | 50.94 | -4.55 |

| 50.01 | 45.53 | -4.48 |

| 48.09 | 43.28 | -4.81 |

| 44.12 | 40.82 | -3.30 |

| 41.93 | 38.73 | -3.20 |

| 37.49 | 36.78 | -0.71 |

| 35.21 | 35.47 | 0.26 |

| 30.94 | 30.84 | -0.10 |

| 28.74 | 30.00 | 1.26 |

| 28.56 | 25.56 | -3.00 |

| 25.64 | 25.35 | -0.29 |

| 25.15 | 22.21 | -2.94 |

| 23.29 | 21.39 | -1.90 |

| 20.95 | 19.83 | -1.12 |

- The output spectrum can be accessed here.

1H NMR

- The output spectrum can be accessed here.

References

- ↑ P. Caramella, P. Quadrelli, L. Toma, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2002, 124, 1130-1131. DOI:10.1021/ja016622h

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 S. W. Elmore, L. Paquette, Tetrahedron Letters, 1991, 319, 483 - 488. DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0

- ↑ L. Paquette, N. A. Pegg, D. Toops, G. D. Maynard, R. D. Rogers, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1990, 112, 277-283. DOI:10.1021/ja00157a043