Rep:Mod:mAm1CJS3

Experiment 1C Part 1

The Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

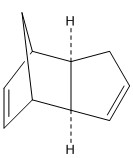

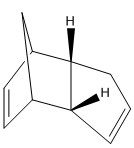

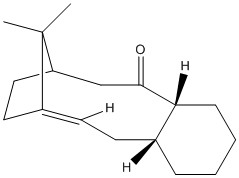

At room temperature, cyclopentadiene spontaneously dimerises to form dicyclopentadiene via a Diels Alder reaction. There are two stereoisomers that can form when cyclopentadiene dimerises, the exo dimer (Dimer 1) or the endo dimer (Dimer 2). These two stereoisomers are formed because the two cyclopentadiene monomers can approach each other in two distinct orientations. However, experimental results have shown that the endo product (Dimer 2) is preferentially formed at room temperature rather than the exo product. The analysis below attempts to justify this finding and to determine whether the dimerisation of cyclopentadiene and the subsequent hydrogenation of the endo dimer is kinetically or thermodynamically controlled. Chem Bio 3D was used to draw the below 2D diagrams and a Jmol 3D model of each molecule appears when the designated buttons are clicked. The 3D models have been energetically optimised and some of their associated bond angles recorded using the force field MMFF94s with the program Avogadro.

|

|

|

|

| Property | Cyclopentadiene Exo

Dimer 1 (kcal/mol) |

Cyclopentadiene Endo

Dimer 2 (kcal/mol) |

Dihydro Dimer 3

(kcal/mol) |

Dihydro Dimer 4

(kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stretching Energy | 3.543 | 3.467 | 3.312 | 2.823 |

| Angle Bending Energy | 30.773 | 33.193 | 31.937 | 24.687 |

| Stretch Bending Energy | -2.041 | -2.082 | -2.102 | -1.657 |

| Torsional Energy | -2.731 | -2.949 | -1.47 | -0.377 |

| Out-of-plane Bending Energy | 0.015 | 0.022 | 0.013 | 0.0003 |

| Van der Waals Energy | 12.801 | 12.356 | 13.637 | 10.635 |

| Electrostatic Energy | 13.014 | 14.183 | 5.12 | 5.147 |

| Total Energy | 55.373 | 58.191 | 50.446 | 41.258 |

Table 1. Optimsed energies for dimers 1-4 using force field MMFF94s with Avogadro.

In a reaction, the kinetically controlled product forms faster than the thermodynamically controlled product because the activation energy for this product is lower than the activation energy for the thermodynamically controlled product. However, the thermodynamically controlled product is more stable. The kinetic product is favored under kinetic conditions and the thermodynamic product is favored under thermodynamic conditions.

The total energy of the exo dimer (Dimer 1) is lower than the total energy of the endo (Dimer 2) product. This indicates that the exo dimer is thermodynamically more stable than the endo dimer. The significant energy diference between dimer 1 and 2 is due the angle bending energy - dimer 1 has 2.42 kcal/mol less than dimer 2. From observing the exo dimer, there is less steric strain due to the two protons that are under the plane of the molecule as opposed to the endo dimer that has those two protons on the top side of the molecule. This causes dimer 1 to have sp3 carbons that are closer to the ideal sp3 bond angle of 109.5 degrees and sp2 carbons that are closer to the ideal sp2 bond angle of 120 degrees. This is illustrated on the 3D models that pop up above. This larger strain that is observed with the endo dimer accounts for the increase in angle bending energy compared to the exo dimer. However, at room temperature, the endo dimer forms because this product is kinetically favoured due to the orbital overlap that occurs at the transition state. If the dimer would be heated to higher temperatures, the thermodynamically stable dimer would form.[1]

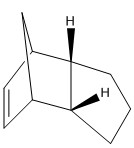

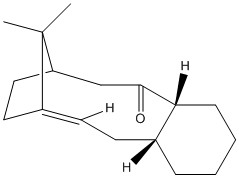

Upon initial hydrogenation of the endo dimer, a dihydro dimer is formed.

The dihydro dimer 4 has the lower total energy compared to dimer 3 and therefore dimer 4 is the thermodynamically stable product. So from a thermodynamical point of view, dimer 4 forms when dimer 2 is hydrogenated. The stretching and angle bending energies are lower for dimer 4 because there is less steric strain in the five membered ring which has the double bond (labelled E - on diagram to the right) compared to the five membered ring which has the double bond (labelled A) in dimer 3. The double bond in dimer 3 measured 1.342A while the double bond in dimer 4 measured 1.338A, this is closer to the ideal bond length of 1.337A as shown in cyclopentene. This justifies the larger stretching energy that dimer 3 has in comparison to dimer 4. Also, the angle in dimer 4, between the double bond and its adjacent C-C bond, is 112.9o and 107.4o in dimer 3. Again, dimer 4 has a bond angle that is closer to its ideal angle as illustrated by the cyclopentene molecule which has this such angle at 111.8o. This explains why the angle bending energy for dimer 3 is larger by 7.25 kcal/mol than for dimer 4. These comparisons confirm that dimer 3 has more steric hinderence in ring A and explains why the stretching energy and angle bending energy for dimer 3 is relatively higher than those energies for dimer 4. The cause of these differences in energies between ring A and ring E is because ring E (which has the double bond) is bonded to the cyclopentane ring (D) at positions C1 and C2. Conversely, ring A (which has the double bond) is attached to the cyclopentane ring (B) at positions C2 and C2 - this causes more strain on the ring. The van der Waals energies are alsovery slightly lower for dimer 4 due to the non bonding interactions that stabilises dimer 4. All these energies discussed contribute to dimer 4 being relatively energetically more stable than dimer 3. The displayed bond lengths and bond angles were optimised and measured using the force field MMFF94s with the program Avogadro.

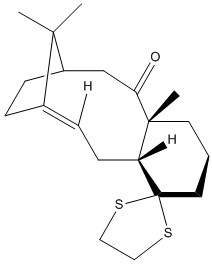

Atropisomers are stereoisomers that can be isolated because of the restricted rotation about a single bond in the molecule. In the synthesis of Taxol, intermediate 9 and 10 are formed and are an example of atropisomerism. The below models were drawn using Chem Bio 3D and a Jmol 3D model of each molecule appears when the designated buttons are clicked. The 3D models have been energetically optimised using the force field MMFF94s with the program Avogadro.

|

|

| Property | Taxol Intermediate 9

(kcal/mol) |

Taxol Intermediate 10

(kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| Stretching Energy | 7.677 | 7.741 |

| Angle Bending Energy | 28.271 | 19.012 |

| Stretch Bending Energy | -0.068 | -0.136 |

| Torsional Energy | 0.246 | 3.762 |

| Out-of-plane Bending Energy | 0.960 | 0.949 |

| Van der Waals Energy | 33.143 | 35.024 |

| Electrostatic Energy | 0.305 | -0.062 |

| Total Energy | 70.537 | 66.292 |

Table 2. Energies for 9 & 10 - optimised using MMFF94s with Avogadro

The significant total energy difference between intermediate 9 and 10 is caused mainly by the angle bending energy and also due to a small difference between the Van der Waals energies. The intermediate 10 has a total energy that is lower than the intermediate 9 and so is the thermodynamically stable product. Initially, intermediate 9 is formed. On standing, the compound isomerises to intermediate 10 and is not able to isomerise back to 9 due to the large angle bending energy difference. This is an example of atropisomerism.

Intermediate 10 is able to adopt a more chair like structure and therefore has a lower angle bending energy by 9.2 kcal/mol. An example that illustrates this point is that intermediate 9 has an angle of 117.4o between its carbonyl group and its neighbouring adjacent carbon, whereas intermediate 10 has an angle of 121.1o at this same position. This shows that there is more angle bending strain in intermediate 9. So the restricted rotation in this example is for the carbonyl group to rotate from under the molecule, to the top side of the molecule due to the increased strain and angle bending energy that would exist.

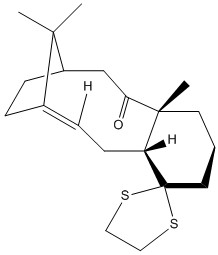

The below two diagrams highlight the important bond lengths that will be used to help explain the Van der Waals energies of intermediates 9 and 10.

|

|

The maximum attraction between two non bonding H...H atoms is when their distance is 2.4 A - anything less than 2.1 A is strongly repulsive. For O...H non bonding interactions, the maximum attraction between these two atoms is when their separation is 2.62 A. Intermediate 9 and 10 show H...H and O...H attractions and repulsions. The attractions contribute to lowering the Van der Waals energy and the repulsions contribute to increasing the Van der Waals energies. Both molecules have similar attractions and repulsions and therefore there is only a difference of 1.9 kJ/mol. Interestingly, the more thermodynamically stable intermediate 10, has the slightly less energetically favourable Van der Waals energies. Moreover, intermediate 10 also seems to have more favourable O...H interactions than does intermediate 9. Intermediate 10 has two favourable O...H interactions (2.612 A and 2.629 A) while intermediate 9 has one favourable (2.683 A) and 2 unfavourable (2.279 A and 2.436 A) interactions. However, intermediate 9 has a total of five H...H interactions that are below 2.4 A while intermediate 10 has a total of 8 unfavourable H...H interactions and these maybe the cause of the Van der Waals energy difference.

Subsequent functionalisation of the alkene bond shows decreased reactivity. This hyperstablility of the alkene is not because of a large steric hinderence for the attacking molecule or due to a strong pi bond. However, it is due to the location of the alkene at the bridghead which leads to enhanced stability that is caused by the cage like structure of this molecule. [2]

Spectroscopic Simulation using Quantum Mechanics

Intermediates 17 and 18 are derivatives of the above intermediates 9 and 10. The H NMR, C NMR spectras and free energies of both compounds have been simulated and compared to literature values. The below models were drawn using Chem Bio 3D and a Jmol 3D model of each molecule appears when the designated buttons are clicked. The 3D models have been energetically optimised using the force field MMFF94s with the program Avogadro.

|

|

| Property | Intermediate 17

(kcal/mol) |

Intermediate 18

(kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| Stretching Energy | 15.964 | 14.433 |

| Angle Bending Energy | 31.394 | 28.869 |

| Stretch Bending Energy | 0.433 | 0.511 |

| Torsional Energy | 13.602 | 13.353 |

| Out-of-plane Bending Energy | 1.096 | 0.979 |

| Van der Waals Energy | 53.638 | 50.450 |

| Electrostatic Energy | -7.129 | -6.201 |

| Total Energy | 108.997 | 102.396 |

Table 3. Energies for 17 & 18 - optimised using MMFF94s with Avogadro

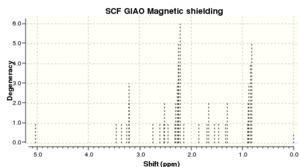

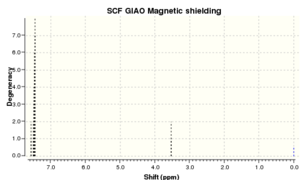

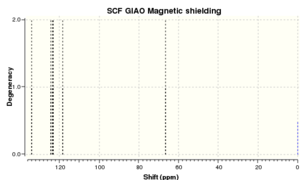

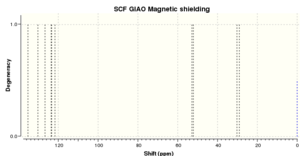

Intermediate 18 is the thermodynamically stable product. The 1H NMR and 13C NMR of intermediates 17 and 18 are presented below and 18 is compared to literature. To simulate a the NMR spectras, the molecules were optimised using MMFF94s in Avogadro and the following parameters were set in Gaussian: Geometry optimisation with a theory of B3LYP and a basis of 6-31G(d,p). The solvent was set as chloroform and the key words FREQ, NMR and EmpiricalDispersion=GD3 included. The H NMR and C NMR results for 18 are tabulated in Table 4 & 6.

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

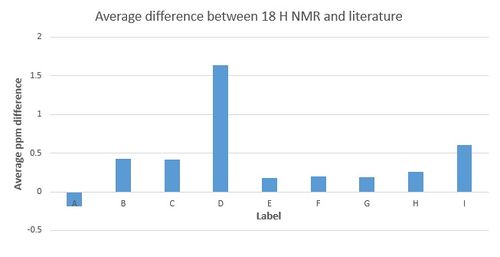

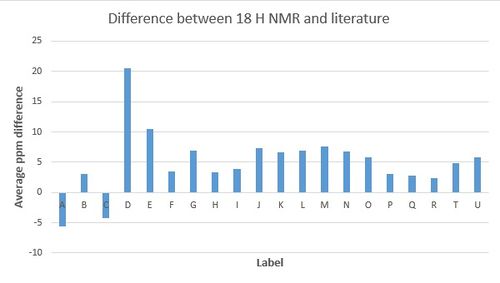

Intermediate 18 H NMR results are compared with a literature source[3] and a graph displaying the average difference between the two sets of results is displayed in Figure 1.

The comparison shows that with the exception of the peak with the highest shift, all the shifts are marginally higher in the literature. The discrepancies between these two sets of results are not consistent and would therefore indicate that there isn't an intrinsic error associated with the simulated results. However, overall the graph shows that most of the peaks are very close in comparison - most of the errors are within 0.5 ppm. It is difficult to accurately compare this literature source to the simulation because the literature says - series of multiplets for 14 H between 2.8 & 1.3 - and therefore it is not known where exactly each hydrogen is. It is because of this that an average has been used to compare but it does mean that the compariosn is not completely accurately.

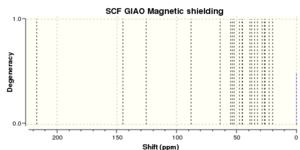

The C NMR results for intermediate 18 are compared with a literature source[3] and a graph displaying the average difference between the two sets of results is displayed in Figure 1.

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The comparison shows that generally speaking the shifts are again higher in the literature. The discrepancies between these two sets of results are not consistent and would therefore indicate that there isn't an intrinsic error associated with the simulated results. Corrections for the simulated results have not been included. Typically, carbons that are attached to heavy elements such as sulphur and carbonyls have shifts which need correction for so-called spin-orbit coupling errors. These correction values have not been calculated in literature and therefore were not included in the comparison here and so it is difficult to give an accurate comparison for these carbons that are affected by the spin-orbit coupling errors. For the carbons that are not adjacent to either a sulphur or the carbonyl group, there is a discrepancy - albeit quite small - between the two sets of results. The average difference between the two sets of results is 5.09 ppm. It may well be that the literature source is mistaken and the simulated shifts are more accurate as the simulated results rely on fundamental quantum mechanics and there is therefore less room for human error.

Table 8 tabulates the relative free energies of the two intermediates. The energies are very similar and 17 has a free energy that is lower by 0.032.

| Intermediate 17 | Intermediate 18 | |

|---|---|---|

| Free Energy ΔG | -1651.451 | -1651.419 |

Table 8. Free energy of 17 & 18

Experiment 1C Part 2

Analysis of the properties of the synthesised alkene epoxides

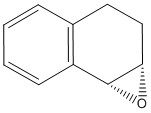

Asymmetric epoxidation, is the ability to prepare chiral compounds in their enantiomerically pure forms. The Shi and Jacobsen catalysts are used in this experiment to enantioselectively prepare different epoxide enantiomers. NMR and optical rotation are amongst the simulated spectroscopic techniques that are discussed below to investigate the epoxides prepared using the Shi and Jacobsen catalyst.

Crystal Structure of Shi and Jacobsen catalyst

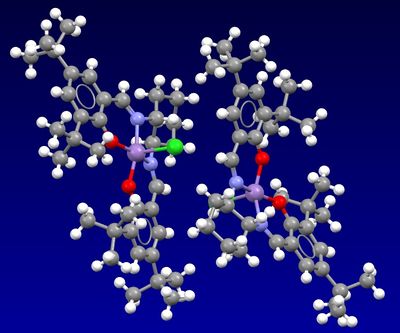

The Cambridge crystal database was searched using the Conquest and Mercury programs for the pre-catalysts 21 and 23. The below crystal structures were found.

|

|

For the Shi pre-catalyst, the C-O bond lengths at the anomeric centres are not equal. This is due to the anomeric effect. The oxygen is able to donate a lone pair into the C-O σ* orbital. This shortens one of the C-O bonds due to the increased bonding interaction and lengthens the other C-O bond because of the population of the antibonding orbital. An example to this in the Shi catalyst (21) are the C-O bond lengths 0.143nm and 0.146nm (as shown on 3D model). The longer (0.146nm) bond length is at its position due to the inductive electron withdrawing effetc that is created by the carbonyl group on the central ring. This carbonyl causes the nearer of the two C-O bonds to have the longer bond length. Another example like this is visible on the 3D model where one C-O bond is 0.142nm and the other C-O bond is 0.145nm, again here the longer C-O bond is the one nearer the carbonyl group.

Upon viewing the 3D model of the crystal structure of the Jacobsen pre-catalyst, it can be seen that there are some close H...H distances between the adjacent tert butyl groups. The 0.242nm H...H distance is strongly attractive and the 0.208 nm H...H distance is strongly repelling. These two interactions influence the van der Waals energy of the crystal packing.[4] A metal centre with 5 ligands can either adopt a trigonal bipyramidal structure or a square pyramidal structure. Molecule 23 adopts the latter. This is because four out of the five ligands are joined via a ring, this means that there is less strain when a square based pyramidal geometry is adopted.

NMR of Epoxides

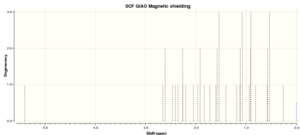

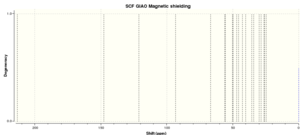

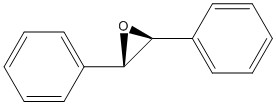

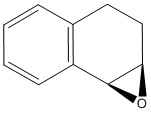

There are two epoxide enantiomers that can be prepared from the epoxidation of the trans-stilbene alkene, one is prepared using the Shi catalyst and the other from the Jacobsen catalyst. The same applies for the epoxidation of 1,2-dihydronaphthalene. The four possible epoxides were modelled uisng Chem Bio and their energies minimized by Avogadro as recorded in table 9. The same technique that was used above for the NMR simulation of the taxol intermediate was used below for the epoxides.

|

|

|

|

| Property | Trans-stilbene epoxide (R,R)

(kcal/mol) |

Trans-stilbene epoxide (S,S)

(kcal/mol) |

1,2-dihydronaphthalene epoxide (R,S)

(kcal/mol) |

1,2-dihydronaphthalene epoxide (S,R)

(kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stretching Energy | 3.726 | 3.726 | 2.699 | 2.683 |

| Angle Bending Energy | 2.693 | 2.694 | 2.178 | 2.118 |

| Stretch Bending Energy | -1.541 | -1.542 | -0.870 | -0.873 |

| Torsional Energy | 2.33 | 2.33 | 1.672 | 1.607 |

| Out-of-plane Bending Energy | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.079 | 0.029 |

| Van der Waals Energy | 26.873 | 26.877 | 19.383 | 19.472 |

| Electrostatic Energy | 5.372 | 5.367 | 5.150 | 5.142 |

| Total Energy | 39.457 | 39.457 | 30.224 | 30.223 |

Table 9. Optimized energies for epoxides

Even though the epoxides have their energies tabulated in one table above - comparisons may only be made between two diasterioisomers and not between two different molecules.

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Trans-stilbene epoxide (R,R) | Trans-stilbene epoxide (S,S) | 1,2-dihydronaphthalene epoxide (R,S) | 1,2-dihydronaphthalene epoxide (S,R) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free Energy ΔG | -615.769683 | -615.769683 | -462.16768 | -462.16768 |

Table 14. Free energies of epoxides

The free energies of each enantiomer is identical with its opposite enantiomer. This is because each enantiomer is a mirror image of the other enantiomer and therefore there is no energy difference between the two geometries adopted. Similarly, the optimised energies in table 9 are identical for both enantiomers of each epoxide.

Assigning the absolute configuration of the epoxides

To assign of the absolute configuration of the epoxides, the optical rotation of each epoxide was simulated and the results compared to literature values that were found using Reaxys. To simulate the optical rotation, the quantum mechanical optimised molecule was used with the B3LYP density functional method and the light wavelength simulated was between 598 nm to 365 nm. The results are displayed in table 15 along with the published DOI that contains the files used in the optical rotation simulation.

| Trans-stilbene epoxide (R,R) | Trans-stilbene epoxide (S,S) | 1,2-dihydronaphthalene epoxide (R,S) | 1,2-dihydronaphthalene epoxide (S,R) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optical Rotation | 298.19o | -298.10o | 155.82o | -158.09 o |

| Published DOI | DOI:10042/25985 | DOI:10042/25986 | DOI:10042/25987 | DOI:10042/25995 |

| Table 15. Optical rotation simulated values | ||||

The above results are in agreement with theory in so far that each enantiomer has the opposite sign and similar magnitude as the opposite enantiomer has. Table 16 tabulates the literature values for these epoxides.

| Trans-stilbene epoxide (R,R) | Trans-stilbene epoxide (S,S) | 1,2-dihydronaphthalene epoxide (R,S) | 1,2-dihydronaphthalene epoxide (S,R) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optical Rotation | 319.8o[5] | -306.0o[4] | 133o[6] | -144.9o[7] |

| Concentration | 0.8 | 1.4 | 0.81 | 0.33 |

| Enantiomeric excess | 93% | 89% | 97% | 95% |

| Solvent | Benzene | Ethanol | Chloroform | Chloroform |

| Wavelength | 589 nm | 589 nm | 589 nm | 589 nm |

| Table 16. Optical rotation literature values | ||||

The signs are in agreement on all four occasions when comparing the simulated results with the literature values. The magnitudes deviate a bit. Theory expects that the magnitude of each enantiomers optical rotation should be identical, however, that is when the product is 100% pure enantiomerically. The cited literatures report ee that are different and a little bit less than 100% and so it is not expected that the optical rotations of each enantiomer quoted to be identical. The simulated values are a lot more precise in that the magnitudes are almost identical. So either the reported ee by the literature citations have caused the magnitudes to be non identical or there is a mistake in the reported values.

Using the calculated properties of transition state to determine enantiomeric excess

The free energies of the transition states for the epoxidation of trans-stilbene(RR) has been used to calculate the enantiomeric excess of this epoxide.

| Transition states for Shi epoxidation of Stilbene | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Label | R,R series | Transition state G | S,S Series | Transition state G | ΔG = RR-SS | K = e^(-ΔG/RT) | Relative amount | ee |

| 1 | DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.828552 | -1534.687808 | DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.829524 | -1534.683440 | 0.004368 | 102.158 | 1:0.009789 | 99.02% |

| 2 | DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.830388 | -1534.687252 | DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.829525 | -1534.685089 | 0.002163 | 9.885 | 1:0.101164 | 89.88% |

| 3 | DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.829522 | -1534.700037 | DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.830389 | -1534.693818 | 0.006219 | 725.649 | 1:0.001378 | 99.86% |

| 4 | DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.829523 | -1534.699901 | DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.830390 | -1534.691858 | 0.008043 | 5009.136 | 1:0.002 | 99.98% |

Table 17.Transition states for Shi epoxidation of Stilbene

The Hartree/partical values that are obtained from the log file of the transition state files are converted to joules/mol in order to keep the units consistant. The transition states for the RR epoxides are all lower than the transition states for the SS epoxides when using the Shi catalyst and therefore the RR enantiomer dominates when the Shi catalyst is used. By method of elimination, the Jacobsen catlyst forms the trans-stilbene SS epoxide to form. The transition state with the smallest ΔG value between the RR and SS epoxide is the one with the most stable route between the two enantiomers and from table 17, the second transition state has the smallest difference in free energy. This transition state however, produced the lowest ee value. This is because, since this transition state has the smallest ΔG, it will be relatively the easiest route for one enantiomer to form to the other enantiomer and therefore the ee of trans-stilbene (RR) is relatively the lowest. The ee values calculated in table 17 from the simulation is similar to the ee value that has been reported in literature and mentioned in table 16.

NCI investigation

The first RR transition state for trans-stilbene was used to simulate the NCI.

Orbital |

The green areas in the above diagram are areas of mildly attractive interactions and the yellow areas are of mild repulsion. The tert-butyl groups of the shi catalyst point away from the alkene and there is significant attraction (green areas) between the oxygens in the catalyst and the alkene. The alkene can be seen to look like it is starting to bend so that the double bond can be nearer the oxygen so that an epoxide will form. This geometry of both molecules causes the energy to be minimised during the transition state. The geometry and direction of the catalyst are what causes this trans-stilbene alkene to form an RR epoxide enantiomer.

QTAIM investigation

The first RR transition state for trans-stilbene was used to simulate the QTAIM.

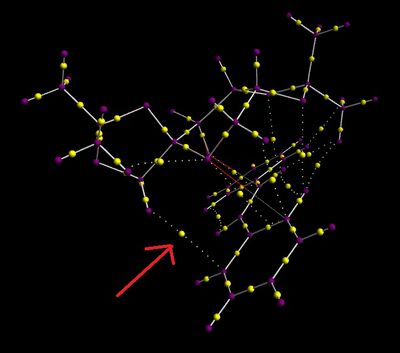

|

The QTAIM diagram shows that there are several points on the during the transition state that a BCP is formed. The one that can be seen from the diagram on the right is the yellow ball that is indicated by the red arrow. This interaction is between a hydrogen on the Shi catalyst and a carbon on the trans-stilbene. This is an example of a weak non covalent interaction.

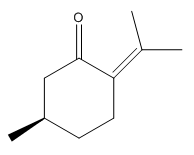

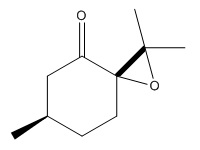

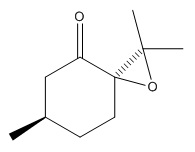

Alternative candidates

An alternative candidate to undergo asymmetric epoxidationis is the alkene (R)-(+)-Pulegone which is commercially available from Sigma Aldrich (CAS 89-82-7). The two epoxides that form are cis R-(+)-pulegone oxide and trans R-(+)pulegone oxide as displayed in diagrams below. The optical rotations of the two epoxides are reported from literature in table 18.

|

|

|

| Cis R-(+)-pulegone oxide | Trans R-(+)-pulegone oxide | |

|---|---|---|

| Optical Rotation | 26o[8] | -19.5o[9] |

| Concentration | 3.1 | 1.5 |

| Solvent | Chloroform | Ethanol |

| Wavelength | 589 nm | 589 nm |

| Table 18. Optical rotation literature values for Pulgone | ||

Software used in this report

The wiki used to write up this report enables the use of 3D Jmol models that gives the reader a better visualisation of the molecule, its bond lengths, angles and geometry. It also allows the author to continuously write up ideas and analyses that are easily recorded using the time stamp - this is very much in keeping with how a chemist works in a wet lab using a lab book. The other advantage to wiki is that it is very easily accessible from anywhere in the world with an internet connection. The disadvantage to wiki can be that it is sometimes difficult (or very time consuming) to create a layout for a piece of work that say, in MS word, would take a few seconds.

Avogadro's option to watch the molecule as it moves to its optimised energy is very useful in understanding why certain geometries are unfavorable for a molecule. This software is also easy to use to record measurements of bond length and angles.

ChemBio 3D doesn't have the option to see the breakdown of the components of the total energy of a molecule as Avogadro does and it does not show the movement of the molecule from an unfavourable energy position to the optimised geometry. However, ChemBio 3D is alot easier and quicker than Avogadro for drawing out molecules.

Gaussview has the options to simulate NMR and optical rotations which is a very useful tool. However, the optical rotation result cannot be viewed in this program.

References

- ↑ Philip J. Wilson, Joseph H. Wells, "The Chemistry and Utilization of Cyclopentadiene", Chem. Rev., 1944, 34, pp1-50 DOI:10.1021/cr60107a001

- ↑ S. Lalithaa, Jayaraman Chandrasekhara, Goverdhan Mehtab, "Cage Geometry Controlled Hyperstability In Bridgehead Olefins", Tetrahedron Letters, 1990, 31, pp4219-4222 DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)97586-5

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Spectroscopic data: L. Paquette, N. A. Pegg, D. Toops, G. D. Maynard, R. D. Rogers, J. Am. Chem. Soc.,, 1990, 112, 277-283. DOI:10.1021/ja00157a043

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 J.W.Yoon, T.-S.Yoon, S.W.Lee, W.Shin "Acta Crystallogr.,Sect.C:Cryst.Struct.Commun.", Acta Cryst., 1999, 55, 1766. DOI:10.1107/S0108270199009397 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "10.1107/S0108270199009397" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Wang, Bin; Wu, Xin-Yan; Wong, O. Andrea; Nettles, Brian; Zhao, Mei-Xin; Chen, Dajun; Shi, Yian "A Diacetate Ketone-Catalyzed Asymmetric Epoxidation of Olefins", J. Org. Chem., 2009, 74 (10), pp 3986–3989. DOI:10.1021/jo900330n

- ↑ Boyd, Derek R.; Sharma, Narain D.; Agarwal, Rajiv; Kerley, Nuala A.; McMordie, R. Austin S.; et al. "A new synthetic route to non-K and bay region arene oxide metabolites from cis-diols", J. Chem. Soc., 1994, 1693-1694. DOI:10.1039/C39940001693

- ↑ Sasaki, Hidehiko; Irie, Ryo; Hamada, Tetsuya; Suzuki, Kenji; Katsuki, Tsutomu "Rational design of Mn-salen catalyst (2): Highly enantioselective epoxidation of conjugated cis olefins", Tetrahedron, 1994, vol. 50, # 41 p. 11827 - 11838. DOI:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)89298-X

- ↑ Robert D. Bach, Russell C. Klix "Synthesis of α-Corocalene", J. Chem. Res. (S), 1998, 80-81. DOI:10.1039/A705069K

- ↑ John Read and Ishbel Grace Macnaughton Campbell "On the geometric requirements for concerted 1,2-carbonyl migration in α,β-epoxy ketones", Tetrahedron, 1985, Volume 26, Issue 8, Pages 985–988. DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)98492-2