Rep:Mod:lt912 mgo

The Free Energy and Thermal Expansion of MgO

Introduction

Background Theory and Simulation Protocols

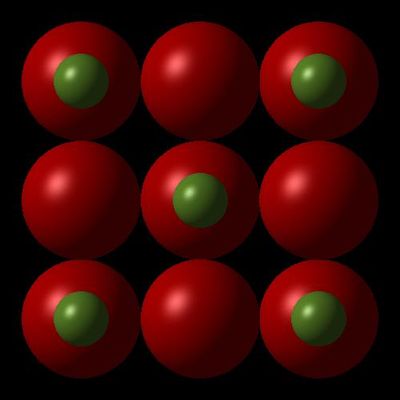

The simulations contained herein were performed using the GULP program and used a primitive MgO unit cell where a = 2.9783 and α = 60.0000°. Internal energy was calculated by placing a force field within a very large number of unit cells. The force field takes into account the attractive and repulsive potentials between the ions of the lattice. Ions placed in force field have a certain energy and the unit cell energy is the sum of the energies of the ions contained within it. It is important to use large numbers of unit cells for these calculations as the internal energy will only approach bulk values when the number of unit cells is large. The internal energy is the binding energy of the lattice and represents the amount of energy required to place all the atoms infinitely far apart.

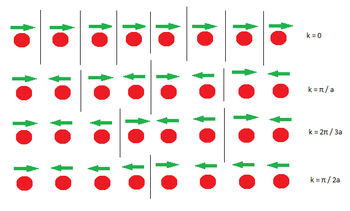

Vibrations in a lattice can be represented graphically by dispersion curves. The curves consist of the k-vector on the x axis and the frequency (and therefore energy) on the y-axis. Each k vector represents a unique vibration and every possible vibration has an associated k vector. It is therefore of some interest to understand how a k-vector is assigned to a vibration. Using the classical definition of a wavevector the only thing left to find is the wavelength of the phonon . In Figure 1 a range of phonons is shown. The arrows represent what direction the atom below is moving relative to the other atoms. The wavelength is the distance along the lattice between unit cells which have atoms of one type moving in tandem, hence the distance is often written in terms of the lattice constant. In Figure 1 each atom is the only member of a unit cell of length a, therefore k can be calculated by counting the number of unit cells that have to be crossed until an atom moving in the same direction is reached. This is then converted to the total length.

As more k values are calculated bands begin to appear on the dispersion graph. The number of bands depends on the dimensionality of the lattice and the number of species present.

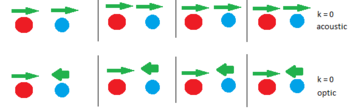

MgO is not a mono-ionic lattice and the presence of two ions allows additional vibrations to occur. Figure 2 shows the k = 0 vibration again, but this time for a lattice of two species such as MgO. The distance between two red ions moving in tandem is the same as before (in terms of a) and therefore k is still 0 however the blue ion can move either in phase or in anti phase with its red counterpart allowing for two energetically distinct modes. The anti-phase optic vibration is higher in energy. As the number of k values sampled increases each mode will form its own band.

While every vibration can in theory be calculated, this would require the sampling of an infinite number of k points and infinite time. As a result a compromise has to be made when calculating dispersion curves. While not all k points will be sampled, there must be enough to give an accurate dispersion curve.

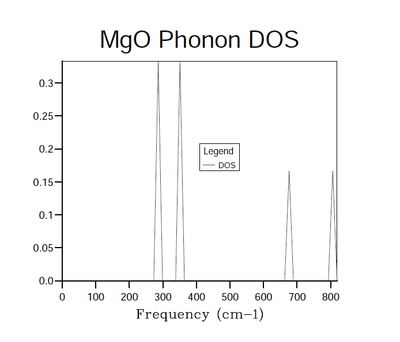

The DOS function maps the number of states at a given frequency ie the number of times the bands on a dispersion curve pass through a frequency. The way this is done is by taking a k value on the phonon dispersion curve and tallying the band frequencies at that point. Therefore to get a complete DOS function all k values should be considered. However this can be computationally unfeasible, and the increased detail as a result of more k values being sampled asymptotically approaches a maximum. Increasing the grid size causes the calculation to check more k points for their frequency values and therefore increases the number of peaks and resolution of the DOS function.

When increasing grid size it is important to not choose values arbitrarily. The simulations were performed used Monkhorst-Pack grids, this means that once the number of k points to be sampled was calculated, k points were chosen so that they were all equally spaced along the Brillouin zone. It is therefore easy to see that when a grid of 8 k points is distributed evenly across the Brillouin zone the positions of those k points will be different than if 9 k points were distributed evenly. Since the investigation is concerned with the effects of larger grid size on the DOS function and not of different k point selection, it is important when increasing grid size that all the k points from the smaller grids are sampled and that any additional k points fall in between those. This is achieved by using a function of the form N = Ax where N is the size of the grid in one dimension, A is a constant and x is a variable. The simulations described in this report used A = 2 resulting in grids 1x1x1, 2x2x2, 4x4x4, 8x8x8 etc.. It worth noting that by using A = 2 some k points will not be sampled when x < infinity. These missing k points would be sampled if another value of A was chosen. For example the Dirac point in graphene is sampled when A = 3 but not 2. These same considerations apply when selecting a grid size for free energy calculations.

Thermal expansion of MgO was also investigated in this report. This is a measure of how much a crystal grows when heated. The growth measured can be linear or volumetric, resulting in linear and volumetric thermal expansion coefficients respectively. The coefficients are a measure of change in size per unit temperature. The microscopic, physical origin of thermal expansion is a result of increasing kinetic energy of lattice particles with greater temperature. When the temperature increases, so does the kinetic energy which means that the average distance between particles is larger and this translates as an expansion on the macroscopic scale in the bulk crystal.

In the harmonic potential the bond length, or rather the equilibrium bond length, does not change with increasing temperature due to the potential being symmetrical. The QHA uses the harmonic potential but the bond length is increased by making phonon frequencies dependent on volume and structure[1]. This is done by incorporating free energy calculations into structure determination. Taking the definition of Helmhotz free energy: the equilibrium structure at any temperature will be the one with the minimum free energy. The U term consists of Coulombic interactions which favour small volumes while the S term consists of vibrations or phonons which favour large volumes. At higher temperatures maximising the S term at the expense of the U term minimises the free energy. As a result thermal expansion takes place. By calculating the thermal expansion the bond lengths in the quasi harmonic approximation are renormalized to match the lattice size.

As the temperature in the QHA simulation approaches the melting point of the lattice, the ability of the simulation phonon modes to represent actual ions deteriorates. This is because anharmonic modes of vibration are not present and because phonon-phonon interactions are not taken into account with this model. Phonon-phonon interactions describe the ability of high energy vibrations to relax through other phonon modes, something which is not possible in the QHA simulation.

Results and Discussion

The internal energy of the MgO crystal at 0.000 K and 0.000 GPa was found to be -41.07531759 eV (-3963.1403 kJ/mole unit cells). The dispersion plot was calculated using 50 points along the W-L-G-W-X-K path, the results are shown in Figure 3.

As expected there are 6 bands present in the phonon dispersion plot. This simulation was performed in 3D space, which means that the atoms have 3 translational degrees of freedom. Rotational degrees of freedom are not present due to the atoms being locked in a lattice. Furthermore in each unit cell, the Mg2+ and O2- ions can vibrate in phase (acoustic) or anti-phase (optic). Therefore 3 degrees of freedom each of which has 2 distinct modes of vibration results 6 distinct bands along k-space. Degeneracy is responsible for some values of k having fewer than 6 bands visible. The 3 bands with a frequency of 0 cm-1 at Γ are the harmonic bands, while the other bands with higher frequencies at this point are the optic bands. This name refers to the fact that phonons in this band can be excited by optical (infrared) frequencies of light.

The DOS function was first calculated at a single k value and the result can be seen in Figure 4. The 4 peaks present in the spectrum can be categorized according to height, with 2 tall peaks of the same amplitude and 2 short peaks also of the same amplitude. The tall peaks are exactly twice the height of the short peaks. Since this is a DOS function at a single k value, it is expected that 6 peaks would appear in Figure 2. This is because each k value maps 6 frequencies due to 6 bands running through the entire phonon dispersion curve in Figure 1. The missing two peaks are shown in the diagram by the increased amplitude of the peaks in the 288.49 cm-1 and 351.76 cm-1 regions, which is a result of 2 bands being degenerate at those points. With the knowledge that we have two degenerate bands at frequencies of 288.49 cm-1 and 351.76 cm-1, as well as single bands at 676.23 cm-1 and 818.82 cm-1, the k point at which this DOS was taken must be point L in Figure 1 as it is the only one with these properties.

|

|

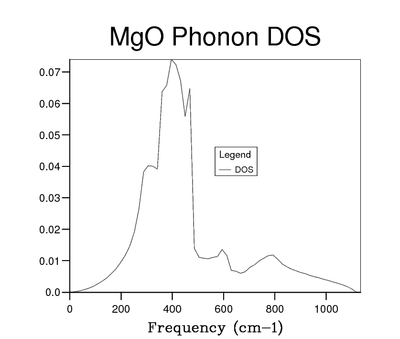

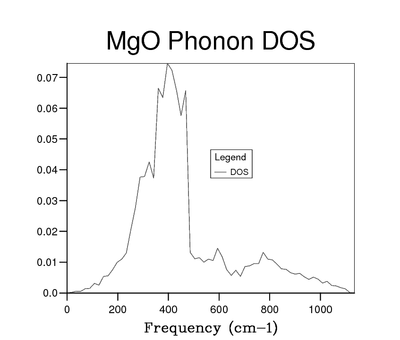

To improve the resolution of the DOS function, larger grid sizes were used. The sizes were selected using the function N = 2x. Grid sizes of 2x2x2, 3x3x3 (due to request from instruction manual), 4x4x4, 8x8x8, 16x16x16, 32x32x32 and 64x64x64 were used. The reason these grid sizes were chosen is explained in the Background Theory section of this report. Initially as the grid size increases the DOS starts to display more peaks. First these are separate but as grid size increases and more peaks appear they begin to join up into a continuous function. Once the whole function is continuous at about the 8x8x8 grid size it is still somewhat noisy and sampling more k points with larger grids causes it to be smoother. At larger sizes, eg 64x64x64, this effect on smoothness also begins to disappear.

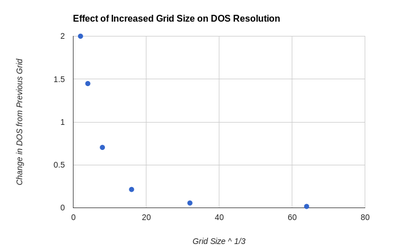

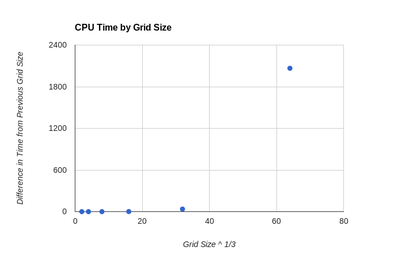

In order to find the optimum grid size 3 factors have to be taken into consideration: accuracy, improvement in accuracy from next smallest grid, time taken for calculation. Accuracy is the most important as even if after very long elapsed time the DOS function produced cannot be used to analyse the system, it is useless. If one does produce an reasonably accurate DOS function it is important to evaluate whether the increase in accuracy by using a larger grid size is worth the wait time needed to produce it, especially since this relationship is not linear.

|

|

While it is possible to look at 2 graphs of DOS functions an evaluate the change qualitatively, in order to assess this in a more rigorous manner a Python script was written. It takes 2 log files, which contain the DOS graphical data, as input. The magnitude of the difference between the y values at each x point is evaluated and summed over the entire graph. The script can be seen in the Appendix section of this report. The result of the sum is then used to asses how increasing the grid size changes the DOS function. This value has to be considered against the elapsed time value which also changes as grid size is increased. As a result both of these are plotted and can be seen in figures 7 and 8. By examining these graphs it is clear that the 64x64x64 grid is not the optimal choice, as the time needed to create it is extremely large compared to the other grids and its increase in resolution is almost 0. A more interesting choice is between 16x16x16 and 32x32x32 grids. The change in elapsed time is much more significant than any of the previous ones (36.83 s), but the increase in accuracy of using the 32x32x32 versus the 16x16x16 is small only 0.056. As a result the 16x16x16 can be considered the optimum size. It can be seen that its absolute accuracy is also quite good by placing it next to the highest resolution DOS function, this can be seen in figures 5 and 6. The difference between those 2 functions was found using the Python script to be 0.044. Interestingly this is smaller than the difference between the 16x16x16 and 32x32x32 grids. Compared to smaller grid sizes the 16x16x16 size is significantly more smooth and as a result clearly shows all the various minima and maxima of the DOS function, something which smaller grids do not.

It may be useful to discuss whether the optimal grid size calculated for MgO is applicable to other materials. The important thing to consider is if one takes a grid of size AxAxA, will the sampled k point density be the same or similar to the MgO case. The reason the density of the grid may change for different materials is that the size of the Brillouin zone is inversely proportional to the lattice constant. Hence if a material has a much smaller unit cell than MgO, its corresponding Brillouin zone will be much larger and a grid of the same size will sample a smaller percentage of the zone. In order to obtain DOS functions of similar accuracy the same relative amount of k points must be sampled.

Therefore, if one considers a similar oxide, such as CaO, the optimal grid size is likely to be similar. CaO has a lattice constant of 4.8105 Å[2] which is relatively close to MgO's at 4.211 Å[3]. This means that the size of the Brillouin zone stays largely the same as does the density of the grid within it. A zeolite such as Faujasite on the other hand, has lattice constant in the range of 24.669 to 24.996 Å, depending on the type[4]. This is significantly larger than MgO and as a result the Brillouin zone of the Faujasite will be smaller. Hence the 16x16x16 grid would sample a much larger percentage of the zone and would likely not be appropriate for calculations as smaller grids would be more optimal. Finally a metal will have a smaller lattice constant than MgO, for example lithium has a lattice constant of 3.44 Å[5]. This means that the Brillouin zone is larger and as a result the 16x16x16 grid would not sample enough k points to provide an accurate DOS function.

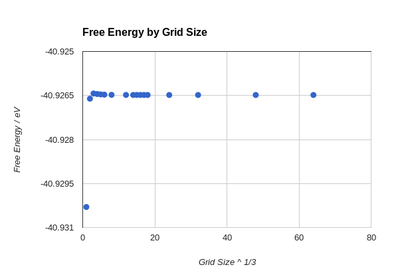

The results free energy calculations at 300 K performed at various grid sizes are shown in Figure 9. As grid size increases the Helmholtz free energy converges to -40.926483 eV (-3948.779647 kJ/mol). The precision of the obtained results was evaluated through 2 methods. In the first, the equation " precisiona×a×a = ±|energya×a×a - energy(a+1)×(a+1)×(a+1)| " was used, where a×a×a denotes the grid size. The second method found magnitude of the difference between the calculated value and the converged value found with the 64×64×64 grid. It can be seen that while the methods are in strong agreement at any grid size, the disparities are smaller as the grid grows larger. Through investigation of Table 1, which holds the calculated precision values, one can conclude that a grid size of 2×2×2 is appropriate for calculations accurate to 1 meV and 0.5 meV while a grid size of 3×3×3 is appropriate for calculations which need to be accurate to 0.1 meV. This is a based on the fact that these are the smallest grids where the uncertainty is smaller than the value to which it is necessary to be accurate to. This can be said with some confidence as both methods agree on the result.

| Grid | Precision using Consecutive Grids / meV | Precision using 64×64×64 Grid / meV | Method Difference / meV |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1×1×1 | ± 3.692 | ± 3.818 | 0.126 |

| 2×2×2 | ± 0.177 | ± 0.126 | 0.051 |

| 3×3×3 | ±0.018 | ± 0.051 | 0.033 |

| 4×4×4 | ± 0.013 | ± 0.033 | 0.02 |

| 5×5×5 | ± 0.008 | ± 0.02 | 0.012 |

| 6×6×6 | ± 0.012 |

In order to find the optimal grid size for this calculation, the number of k points used to calculate the free energy was progressively increased. The initial grid sequence tested a series of Monkhorst-Pack grids of dimensions 1×1×1, 2×2×2, 4×4×4, 8×8×8, 16×16×16, 32×32×32, 64×64×64. The size of the grid increased by N = 2x, for the same reasons as in the DOS calculation. The optimal grid size in this case is the smallest grid size which obtains the correct value to 8 s.f., the highest accuracy obtainable using GULP. The value of -40.926483 eV was labelled as 'correct' as it does not change when grid size is increased, for example up to 64×64×64. This means that while larger grid sizes will obtain the same value to 8 s.f. they will take longer to do it and are therefore not optimal.

Since both the 32×32×32 and 64×64×64 grids find the same answer for the free energy, indicating that this is the correct value, an investigation was undertaken to find what the smallest grid size that also finds it. As a result the sizes between 16×16×16 and 32×32×32 were checked, since 16×16×16 was the largest grid size to not output the converged value. Checking grid sizes between 16×16×16 and 32×32×32 means that different k points will be sampled by each grid. This may cause different energies to be calculated not because of larger grid density but instead due to k point selection. However our calculation shows a steady, noise-less convergence to -40.926483 eV. If k points were affecting the calculated energy to a significant degree, some noise would be expected in the calculated energies, as the increase in density could be offset by a different set of k points finding a lower energy value. Since this was not observed the assumption that sampling different k points has negligible effect on the calculation in this case seems to hold.

The optimal grid size was found to be 18×18×18. It is the smallest grid size which obtains the correct value to 8 s.f.. Larger grid sizes found the same value but took longer to do it, making them sub-optimal. For example the 64×64×64 grid took 2068.6872 seconds while the 18×18×18 grid took only 1.9336 seconds , over 1069 times faster. In some cases it may be optimal to obtain a figure accurate to fewer s.f. to reduce computational time further, however these calculations are performed quickly and therefore this is not a concern. It is noteworthy that this grid size is very close to the optimal size for the DOS function.

Regarding the applicability of this grid size to other materials, the same arguments and conclusions can be reached as when selecting the optimum grid size for the DOS function.

|

|

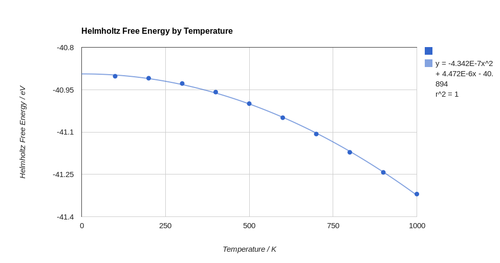

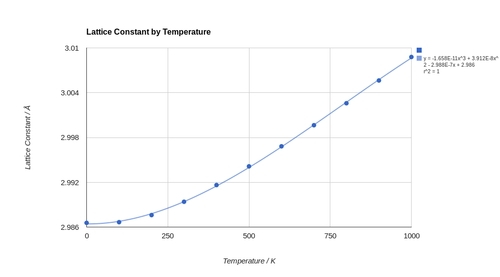

The investigation of thermal expansion of MgO, using the quasi-harmonic approximation, occurred between 0 and 1000 K in steps of 100 K. The optimised Helmholtz free energies and lattice constants were noted. The relationship in both cases is non-linear. The relationship of the lattice constant with temperature is well approximated by polynomial equations of order 3 and up, with the larger orders allowing for better fits to data. While a second order polynomial may be used to some degree of success as well, it deviates noticeably as from the data points as temperature tends to 0 K, especially when compared to the higher order functions. As a result a third order polynomial was chosen to describe the relationship between the lattice parameter and temperature as this is a compromise between simplicity and accuracy. The non-linear nature of this relationship means that the linear thermal expansion coefficient for MgO is different at each temperature. The dependence of free energy on temperature is well approximated by a second order polynomial.

Using the data collected, the linear thermal expansion coefficient for MgO was calculated using the following formula α = Δl/(l0 × ΔT). This was done between every 2 adjacent data points collected. An average across the entire range was not performed as, based on our previous analysis of the graph, the lattice constant is not the same at all temperatures. For example the increase in the lattice constant from 0 to 100 K is far smaller than that between any other 2 temperatures. This means that the thermal expansion coefficients in these two ranges will be different. The calculated thermal expansion coefficients are tabulated in Table 2 and compared to experiment.

| Temperature Range / K | Thermal Expansion Coefficient / µK-1 | Experimental Value of Thermal Coefficient / µK-1[6] | Magnitude of Difference / µK-1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 - 100 | 0.315 | 0.7 | 0.385 |

| 100 - 200 | 3.17 | 2.9 | 0.27 |

| 200 - 300 | 5.98 | 9.4 | 3.42 |

| 300 - 400 | 7.49 | 10.7 | 3.21 |

| 400 - 500 | 8.38 | 12.7 | 4.32 |

| 500 - 600 | 8.97 | 13.4 | 4.43 |

| 600 - 700 | 9.42 | 13.9 | 4.48 |

| 700 - 800 | 9.82 | 14.3 | 4.48 |

| 800 - 900 | 10.1 | 14.6 | 4.5 |

| 900 - 1000 | 10.5 | 14.8 | 4.3 |

The experimental data collected by Suzuki was taken between 23 and 73 K in each range (123 - 173 K, 223 - 273 K etc.) and agrees relatively well with our simulations. The closest agreement occurs between 0 and 200 K where the largest discrepancy is 0.385 µK-1. The disagreement then shoots up to and fluctuates about 4.4 µK-1 for higher temperatures. The main approximation in our calculation is that the calculated α is a constant within the temperature range and and not a function of temperature. As a result the reported value is the average α in that range.

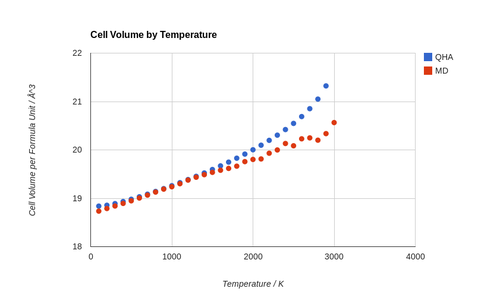

Calculation of the cell volume at different temperatures using MD gave some interesting insights. It can be seen from Figure 12 that MD predicts a smaller cell volume than the quasi-harmonic approximation. While there is a difference in the predicted values, the two methods agree more as the temperature moves from 0 to 1200 K. At this point the predicted cell volume differs only by 0.012 Å3. After this point the predicted volume again diverges, reaching a difference of 0.99 Å3 at 2900 K. Furthermore, the value predicted by QHA is always higher than that predicted by MD. At lower temperatures this is likely, at least in part, to be due to the fact QHA takes into account quantum effects.

The relevant example in this case is zero-point energy, which is accounted for in QHA but not in MD. This means that as the temperature approaches 0 K in the QHA the atoms will have some residual vibrational energy making the unit cell somewhat larger than in the MD case, where they become stationary at 0 K. This effect diminishes in significance as temperature increases and thermal vibrations become dominating, which explains why the cell volumes agree more at higher temperatures.

At high temperatures (greater than 1200 K), the QHA finds that the cell volume continues to increases exponentially until the melting point. Whereas with MD the increase in cell volume is more gradual. Notably the MD data become quite noisy towards the melting point, likely due to the increased movement of atoms causing greater fluctuation in averages. A fix for this could be the use of a larger cell. In order to get a good free energy calculation a total of 5832 (18×18×18) k points were sampled. By analogy in MD it may be desirable to have 5832 MgO units in a cell to provide a good output. However since the cells are of different shape this analogy is not very accurate and a good MD output would likely be generated with far fewer atoms.

The larger predicted value by QHA at temperatures greater than 1200 K can be attributed to its use of a harmonic potential rather than an anharmonic potential as used by MD. The QHA fails to account for the how large amplitude vibrations cause changes in bond length, something which the anharmonic potential used by MD does. The lack of high order anharmonic terms in the QHA was also used to explain the higher predicted volume of MgSiO3 in QHA versus MD by Masanori Matsui et al.[7], which is a further reason to think this was the culprit here also.

The lack of the anharmonic term in the QHA also means that the model is unable to simulate the phase transitions that occur at high temperature. The model in fact breaks down when trying to simulate a lattice above its melting temperature. This is due the harmonic potential which it uses having no analogue of bond breaking, or dissociation energy. This is not the case with MD which uses an anharmonic potential and can be used to simulate both liquid and solid phases. An approximation of the melting point of MgO was made by finding the temperature at which the breakdown occurs. This was found to be in the range from 2960 to 2975 K. This agrees well with the experimental result of 2827 °C [8].

In order to quantify the cell volume expansion, the volumetric thermal expansion coefficient, αV, was calculated for both quasi-harmonic approximation and MD. Experimental results for the volumetric expansion coefficient obtained in the range 77 to 1315 K were compared to the results obtained here, by averaging the calculated αV values in the temperature range from 100 to 1300 K. This is shown to be a good approximation as our results using this method 26.84 µK-1 using QHA and 30.62 µK-1 using MD agree well with the experimental value of 35.7 µK-1[9]

| Temperature Range / K | αV QHA / µK-1 | αV MD / µK-1 |

|---|---|---|

| 100 - 200 | 9.521 | 28.83 |

| 200 - 300 | 17.94 | 27.57 |

| 300 - 400 | 22.49 | 28.36 |

| 400 - 500 | 25.14 | 28.34 |

| 500 - 600 | 26.93 | 30.41 |

| 600 - 700 | 28.29 | 31.55 |

| 700 - 800 | 29.48 | 33.07 |

| 800 - 900 | 30.47 | 31.99 |

| 900 - 1000 | 31.46 | 25.64 |

| 1000 - 1100 | 32.44 | 32.59 |

| 1100 - 1200 | 33.45 | 38.50 |

| 1200 - 1300 | 34.50 | 30.56 |

| 1300 - 1400 | 35.61 | 27.48 |

| 1400 - 1500 | 36.80 | 24.58 |

| 1500 - 1600 | 38.09 | 22.16 |

| 1600 - 1700 | 39.51 | 19.39 |

| 1700 - 1800 | 41.09 | 23.71 |

| 1800 - 1900 | 42.85 | 47.75 |

| 1900 - 2000 | 44.85 | 22.79 |

| 2000 - 2100 | 47.16 | 5.21 |

| 2100 - 2200 | 49.86 | 59.58 |

| 2200 - 2300 | 53.10 | 33.96 |

| 2300 - 2400 | 57.07 | 66.71 |

| 2400 - 2500 | 62.14 | -23.19 |

| 2500 - 2600 | 68.91 | 71.60 |

| 2600 - 2700 | 78.66 | 9.387 |

| 2700 - 2800 | 95.09 | -23.51 |

| 2800 - 2900 | 129.52 | 67.10 |

The value of αV obtained by the two methods agree especially well in the temperature range from 300 to 1400 K, although at all temperatures they fall within the same order of magnitude which is still a degree of success. There are large fluctuations in the value of αV obtained by MD above 1800 K, this is likely to be for the same reasons given above to explain the fluctuations in its prediction of cell volume.

Conclusion

The quasi harmonic model was successfully used to calculate a range of properties of the MgO lattice. These included the internal energy, free energy, dispersion curves, DOS curves, thermal expansion and melting point. The validity of this model has largely been confirmed and supported by close agreement with experimental results. The limits of this model were found to be near the melting point of MgO, however low and medium temperatures show strong predictive power. The failures of the quasi harmonic model have been attributed to its lack of consideration of anharmonic vibrations. Optimum Grid sizes for DOS and free energy calculations were found.

Molecular Dynamics calculations were also carried out, showing agreement with the lattice dynamics model at low and medium temperatures. At high temperatures molecular dynamics was found to be the superior model, however it reliability is strongly dependent on the size of the simulated system. Conversely MD fails at low temperatures where it does not account for dominating quantum effects such as zero point vibrations.

Appendix

Python script used for DOS comparisons:

| import os as os

os.chdir("C:\Users\Guilherme 1\Desktop\Lukas") file1 = open("MgO_5323232.out","r") file2 = open("MgO_6646464.out","r") take_line = False sep_count = 0 file1_yvalues = [] file2_yvalues = [] for line in file1: if line[1:10] == "Frequency":

take_line = True

continue

if take_line == True:

if line[0] == "-":

sep_count += 1

if sep_count == 2:

break

continue

line = line.split(" ")

line2 = []

for x in line:

if x != "":

line2.append(x)

file1_yvalues.append(float(line2[len(line2)-1]))

take_line = False sep_count = 0 for line in file2: if line[1:10] == "Frequency":

take_line = True

continue

if take_line == True:

if line[0] == "-":

sep_count += 1

if sep_count == 2:

break

continue

line = line.split(" ")

line2 = []

for x in line:

if x != "":

line2.append(x)

file2_yvalues.append(float(line2[len(line2)-1]))

total_diff = 0 for x in range(0,len(file1_yvalues)): diff = abs(file1_yvalues[x] - file2_yvalues[x]) total_diff += diff print total_diff |

References

<references> Template loop detected: Template:Reflist

- ↑ Martin T. Dove (1993). "Introduction to Lattice Dynamics". JCambridge University Press 1: 258. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511619885.

- ↑ P S Miedema, H Ikeno, F M F de Groot (2011). "[[First principles multiplet calculations of the calcium L2,3 x-ray absorption spectra of CaO and CaF2]]". J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 23: 1-8. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/23/14/145501.

- ↑ Collaboration: Authors and editors of the volumes III/17B-22A-41B (2006). "Magnesium oxide (MgO) crystal structure, lattice parameters, thermal expansion". Landolt-Börnstein - Group III Condensed Matter Numerical Data and Functional Relationships in Science and Technology 41B: 6. doi: 10.1007/10681719_206.

- ↑ E. Dempsey, G. H. Kuhl, D. H. Olson (1969). "Variation of the lattice parameter with aluminum content in synthetic sodium faujasites. Evidence for ordering of the framework ions". J. Phys. Chem. 73: 387–390. doi: 10.1021/j100722a020.

- ↑ K Doll, N M Harrison, V R Saunders (1999). "A density functional study of lithium bulk and surfaces". J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 11: 1-14.

- ↑ Isao Suzuki (1975). "Thermal Expansion of Periclase and Olivine and their Anharmonic Properties". J. Phys. Earth 23: 145-159. doi: 10.4294/jpe1952.23.145.

- ↑ Masanori Matsui, Geoffrey D. Price, Atul Pate (1994). "Comparison between the lattice dynamics and molecular dynamics methods: calculation results for MgSiO3 perovskite". Geophysical Research Letters 21: 1659-1662. doi: 10.1029/94GL01370.

- ↑ A. Ansary Yar, M. Montazerian, H. Abdizadeh, H.R. Baharvandi (2009). "Microstructure and mechanical properties of aluminum alloy matrix composite reinforced with nano-particle MgO". Journal of Alloys and Compounds 484: 400-404. doi: doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2009.04.117.

- ↑ Joseph R. Smyth, Steven D. Jacobsen, Robert M. Hazen (2000). "Comparative Crystal Chemistry of Dense Oxide Minerals". Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry 40: 157-186. doi: 10.2138/rmg.2000.41.6.