Rep:Mod:lllmmm

Computational Inorganic Module 2

Borane

Optimization

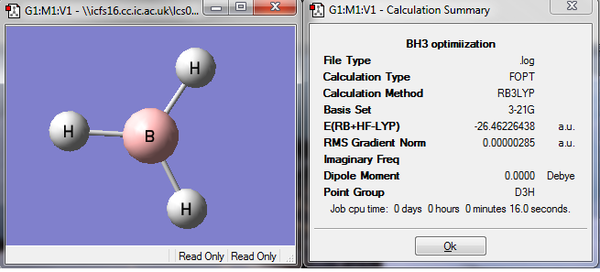

A BH3 fragment was drawn in Gaussview and manipulated to become familiar with the gaussview program. The B-H bond length was 1.18 angstroms and the H-B-H bond angle was 120 degrees. Each bond length was then changed to 1.5 angstroms using the bond distance button, then using this modified molecule an optimization calculation was run using 3-21G basis set and the B3LYP method. The resulting log file was opened in Gaussview, the optimized molecule and summary are shown below. The 'real' (the text based log file) output was also examined to check the job had really converged. The optimized B-H bond length is 1.19 angstroms and the H-B-H angle 120o.

Optimization graphs were also generated, the first graph shows the the energy of the molecule at each step of the optimization and the second gives the the gradient of the energy of the molecule at each step of the optimization. The gradient is the rate of change of energy with respect to the number of iterations i.e the number of times the geometry of the molecule is being modified. The calculation that is run uses the assigned basis set to attempt to simulate the molecule, the input molecule is assessed and the structure is modified depending on the imbalance of repulsive and attractive forces. The calculation changes the geometry to minimise the energy and each change of geometry reduces the energy by a smaller amount as the minimum energy is approached, hence as the energy converges the gradient becomes zero. Both graphs are shown in Fig.2 and it can be seen on the 5th iteration that the energy converges and the gradient becomes zero.

MO Analysis

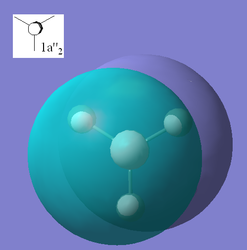

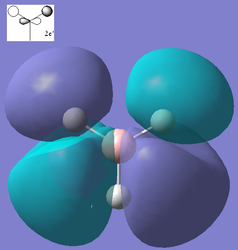

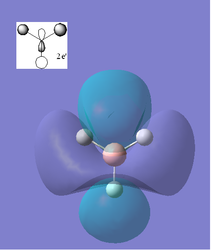

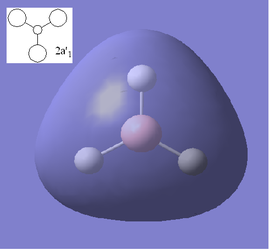

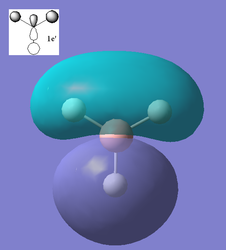

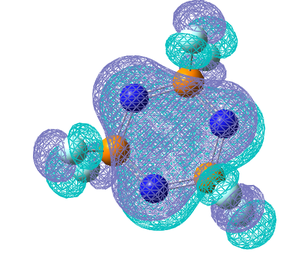

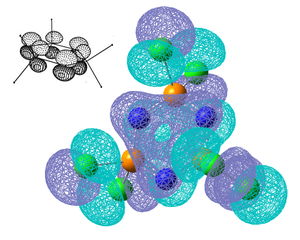

Using the optimized structure of BH3 a calculation was run to solve the electronic structure and obtain the MO's. These quantitative MO's can then be compared to qualitative MO's obtained from MO diagrams. Shown below is the molecular orbitals constructed from a qualitative molecular orbital diagram using the linear combination of molecular orbitals approach (LCAO) along with quantitative molecular orbitals obtained from the calculations.

|

|

|

|

From the above comparisons it can be seen that the molecular orbitals computed using the the 3-21G basis set are similar to those obtained using the LCAO apprach by drawing a molecular orbital diagram. The computed MO's provide more detailed information on the 3D character of the orbitals which is an advantage however when the AO's that have been used to create the qualataive MO's are looked at and imagined how they would interact similar results are obtained. The LCAO method is qualitative and only orbitals up to the LUMO+3 are obtained where as the computational results go up to the LUMO+10 so this method may be necessary if the excited states of the molecule needed to be considered. The ordering of the high energy orbitals in the two approaches are slightly different. In the MO diagram the highest energy orbitals are shown to be degenerate and correspond to the computed orbitals 6 and 7, where as the computed MO 8 is shown to be the third highest on the MO diagram. This difference is due to the large difference in the methods employed, the computational techniques producing quantative results show that MO 6, MO 7 and MO 8 are are all very similar in energy compared to the lower energy orbitals, hence when the qualitative analysis is carried out (LCAO) the ordering of these orbitals is disputable. Using a different basis set in the computational calculations may have yielded slightly different ordering. Another difference is that the computed LUMO appears to be very diffuse more so than would be expected for a p orbital, this is because when calculating the MO's the unoccupied MO's are not calculated as accurately as the occupied MO's, this may also account for the different ordering of the higher energy orbitals.

NBO Analysis

A natural bond orbital analysis was also carried out. The charge distribution across the molecule can be observed visually by assigning colours to to different degrees of positive and negative charge, as expected to the lewis deficient boron atom is positively charged. The charge is also assigned numerically showing the charge on the B atom to be 0.331 and on the H atoms to be -0.110.

Assessing the contribution of each atom to a bond and which orbitals from that atom are involved in the bond is what can be obtained from the natural bond order calculations. The information can be found in this log file: Media:log_36236NBOBH3.LOG and is summarised in the table below.

| NBO | % Contribution from each atom | % Hybridisation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | H | s | p | |

| B1-H2 | 44.48 | 55.52 | 33.33 | 66.67 |

| B1-H3 | 44.48 | 55.52 | 33.33 | 66.67 |

| B1-H4 | 44.48 | 55.52 | 33.33 | 66.67 |

| B Core | 100.00 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 0.00 |

| B Lone Pair | 100.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 100.00 |

The occupancy of all the B-H bonds and the B core was found to be 1.99, i.e approximately 2 in agreement with the traditional picture of a 2 electron bond. The energies of all the B-H bonds are the same and have the negative value and the B core is much lower in energy. However the B lone pair has a much higher energy. If their were secondary orbital interactions present in the BH3 molecule these could be seen under the section "Second Order Perturbation Theory Analysis of Fock Matrix in NBO Basis" in the log file, however none are present here indicating there are no interactions between the B lone pair and any antibonding orbital.

Vibrational Analysis

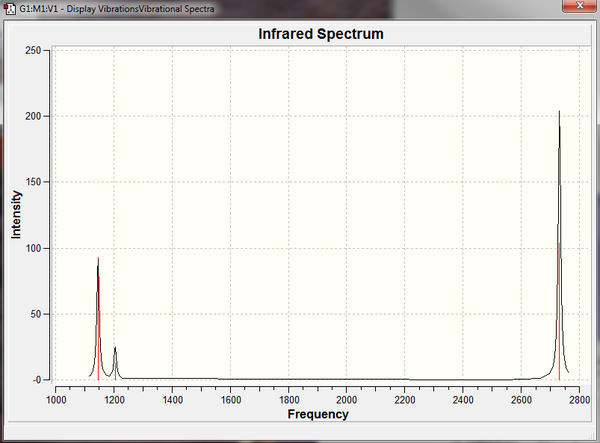

Next a frequency analysis on the fully optimised structure above was carried out. On computing the frequency's the second derivative of the poteintial energy surface is being found, which means that the curvature of the potential energy surface is being found around the optimised structure. If all the frequencies are positive then a minimum point has been found if one of the frequencies is negative then a transition state has been found and if more then one frequency is found to be negative then a critical point has not been found and optimisation has not worked. Of course the frequencies obtained from this analysis can also be used to obtain the IR spectra which can be compared to literature. In the log file it is possible to find the "low frequencies" of the molecule, these are the frequencies of the motions of the centre of mass of the molecule, i.e translational motion in the x,y and z coordinate and rotation of the whole molecule on these three axis. These frequencies are usually zero, however here they are larger due to inaccuracy of the calculations but the highest 'zero' frequency is 21 cm-1 which is an order of magnitude smaller then any of the normal vibrations indicating that the results are ok.

The normal vibrations can then be visualised in gaussview, the 6 vibrations are shown in the table below.

| Mode # | Vibration | Freq./ cm-1 | Intensity | Symmetry D3h point group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

1145 | 93 | A2' | |||

| 2 |

|

1204 | 12 | E' | |||

| 3 |

|

1204 | 12 | E' | |||

| 4 |

|

2593 | 0 | A1' | |||

| 5 |

|

2731 | 104 | E' | |||

| 6 |

|

2731 | 104 | E' |

All the frequencies are positive confirming that the optimization calculations found the minimum energy conformation. Non linear molecules have 3n-6 vibrational modes hence why BH3 has 6 vibrational frequencies, however clearly the IR spectrum exhibits only 3 peaks. This is because two sets of vibrations are degenerate, (2 and 3 + 5 and 6) hence overlap on the spectrum and appear as one peak. Also vibration 4 has an intensity of zero because during the vibration there is no overall change in the dipole of the molecule which is indicated by the symmetry of the vibration and the vibration is IR inactive.

TlBr3

Optimization

A molecule of TlBr3 was drawn in Gaussview and its symmetry was restrained to D3h point group within 0.0001 tolerance. Similar calculations that were run on BH3 are going to be ran on TlBr3 however the atoms being used now are much larger and contain many more electrons which would result in long and expensive calculations, to avoid this problem pseudo-potentials (PP) are used. A PP is a special function which models the core electrons of an atom and can be used in calculations to yield accurate results quickly. Of course the assumption that it is only the valence electrons which participate in the bonding interactions will be employed here. Also when dealing with non first row elements a more complex basis set needs to be used as the molecules have a more complex electronic structure and cannot be accurately described by the basic basis set 3-21G used in BH3.

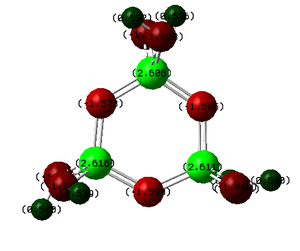

Taking this into consideration an optimization calculation was run on TlBr3 using the basis set LanL2DZ (a medium level basis set) and the DFT/B3LYP method. The optimized structure and summary of the optimization are shown in Fig.5 and the log file for the optimization here. Media:TLBR3OPTlcs.LOG

| Experimental | Literature[1] | |

|---|---|---|

| Tl-Br bond length | 2.65Å | 2.563Å |

| Br-Tl-Br bond angle | 120° | 120° |

The Bond length in the optimization structure is similar to that found in literature, a bond length identical to literature value is not expected due to the approximations used in the calculations, however the value obtained is very similar indicating the correct structure has been found.

Vibrational Analysis

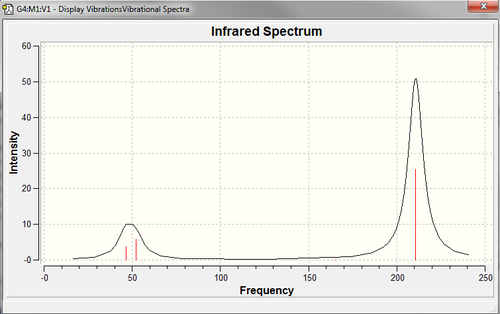

A vibrational analysis was then carried out, as explained earlier this can confirm if a minimum on the potential energy surface has been found and hence the optimized structure found is in fact the lowest energy conformation. The same basis set and method was used as only then are the frequency calculations valid to confirm the optimized structure is a minima. The low and normal frequencies are shown below all the low frequencies are within 10cm-1 of the expected zero value therefore the calculation can be considered have relatively accurate results and the lowest "real" normal is 46cm-1 The output log file for this calculation is shown here. Media:TLBR3FREQLCS.LOG

| Low frequencies (cm-1) | -3.42 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.94 | 3.94 |

| Normal frequencies (cm-1) | 46 | 46 | 52 | 165 | 211 | 211 |

The stretching frequencies of TlBr3 are shown here like for BH3, as both molecules have the same structure and point group the motions of the vibrations are identical. However the ordering of the vibrations frequency values is slightly different while the relative intenisty of the vibrations in the IR spectrum appear to be similar with the last set of degenerate vibrating modes the having the highest frequency and intensity in both molecules. Also the symmetric A1' stretch is again IR inactive. Despite the similarities in the motions of the vibrations the huge difference in the actual frequencys between the two molecules is important. The frequency value are obtained from the curvature of the potential energy surface around the minimum point, therefore the much larger values observed for the BH3 could be indicative of a much steeper minimum and therefore stronger shorter bonds. However the frequency is heavily dependant on the mass of the atoms in the molecule and therefore the large difference in stretching frequencies is much more likely to be down to the large difference in masses of the two molecules. TlBr3 contains much heavier atoms therefore the stretching frequencies are much lower.

| Mode # | Vibration | Freq./ cm-1 | Intensity | Symmetry D3h point group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

46 | 4 | E' | |||

| 2 |

|

46 | 4 | E' | |||

| 3 |

|

52 | 6 | A2' | |||

| 4 |

|

165 | 0 | A1' | |||

| 5 |

|

211 | 25 | E' | |||

| 6 |

|

211 | 25 | E' |

When optimizing a structure Gaussview draws a lot of information from a chemical database which is based on primarily organic molecules, this information is used to draw bonds between atoms depending on whether there is enough electronic interaction to be considered as a bond. Therefore sometimes the molecule that comes out of an optimization calculation can appear to be missing some bonds, this does not mean that there isn't any bonding interactions between the two atoms but said bond does not conform to one of the systems bond distance criteria contained in the chemical database. This means that gaussview has its own definition of what a bond is between to atoms, but this clearly must be different to what we think a bond is if we are expecting bonds where gaussview doesn't. Most simply a bond is something that joins two atoms together and is made up of two electrons and a bond will form if the two atoms are within a certain distance, have the correct symmetry for the orbitals to overlap and are of similar energy. However this simplistic model does not fully describe the bonds in a molecule as can be seen when the molecular orbitals of a molecule are considered and as seen for earlier these moleculer orbitals are not as simple as sigma and pi bonds. In conclusion a bond is perhaps more of a practical tool to observe the structure of the molecule whereas the actual bonding interactions are spread across the molecule.

Isomers of Mo(CO)4L2

Introduction

Here two isomers of Mo(CO)4L2 will be investigated where L=PPh3. The structures of both the cis and trans isomer will be optimized to determine which is the more stable isomer. However PPh3 ligands are big and would take a long time for gaussian to run calculations, therefore Cl atoms will be used instead. Darensbourg et al[2] reported the trans isomer to be the thermodynamically most stable isomer. As well as determining the most stable isomer a frequency analysis will be carried out to confirm that the optimized structure is a minima on the potiential energy surface of these molecules, this frequency analysis will also allow confirmation of the stereochemistry of each isomer.

The cis and trans isomers have different symmetry properties hence they are in different point groups, it is possible to use group theory to predict the number of IR active frequencies. The most useful of these frequencies to analysis are the C=O stretching frequencies. These frequencies usually appear in the region of 1700-2100cm-1 and are convenient as in these complexes no other functional group will cause interference in this region. The point group of the cis isomer is C2v and each of the four irreducible representations that contribute to this reducible representation are IR active as there is a change in the dipole moment of the molecule. Therefore it is expected that there will be 4 IR active C=O stretching frequencies. Where as the trans isomer belongs to the point group D4h and only one IR active frequency is observed as the symmetric stretch of the C=O ligands does not change the dipole moment of the molecule and the frequency is IR inactive. However it is likely that in experimental cases (i.e IR frequencies that have been observed experimentally not computed) that due to perturbations which would mean that the complex would temporarily loss its D4h symmetry and other C=O stretching frequencies may be observed. These predictions fit the general rule that the more symmetric a molecule the less IR active frequencies will be present.

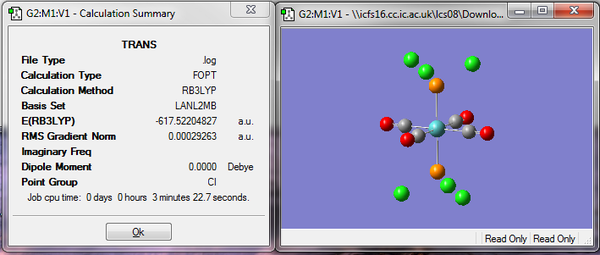

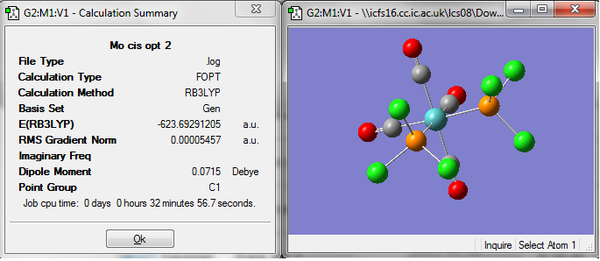

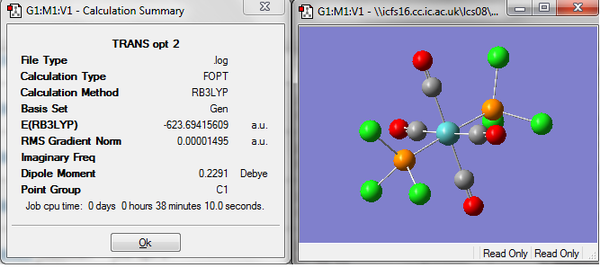

Optimization

To obtain good results for the optimization it must be carried out in three steps, the first optimization was carried out using the B3LYP method and the low level basis step LANL2MB this will get the rough geometry correct. The key words "opt=loose" were added, this is necessary because the method being employed is not that accurate therefore the convergence criteria must also be altered so that limits are not more accurate than the method. The summary and optimized structure from this first step are shown below.

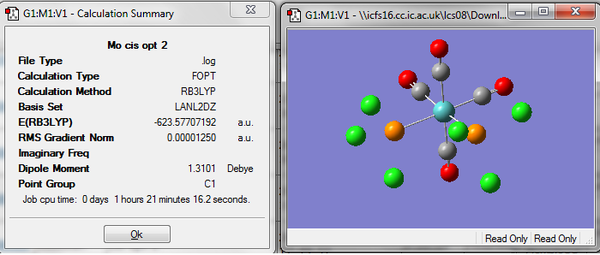

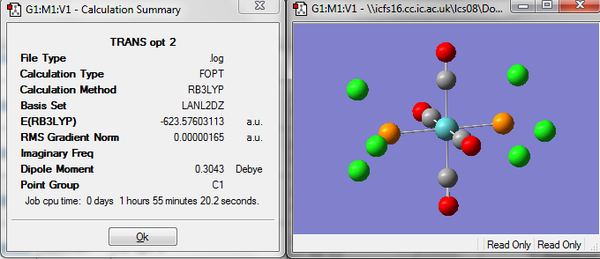

Before the second optimization some changes were made to the above structures to make sure that the correct minimum is found by gaussian. It is the torsion angle of the PCl3 groups that are altered, in the cis isomer the PCl3 groups were rotated so that one of them a Cl atom was pointing up parallel to one of the axial bonds. Then the other P ligand was rotated so that one of the Cl groups was pointing down parallel to one of the axial CO ligands. In the trans isomer the PCl3 ligands were rotated so that they were eclipsed and one Cl was parallel to a Mo-C bond. The second optimization was then run on these adjusted structures, the same method (B3LYP) was used but the LANL2DZ pseudo-potential and basis set was used which is much better than the minimal basis set used previously. Tighter convergence criteria are now needed and the keywords"int=ultrafine scf=conver=9" were added. The optimized structures, their summary which displays the energy amongst other things and the link to the file in D space are shown below.

However there is still a small problem with these optimised structures, the LANL2DZ pseudo-potential and associated basis set are not quite good enough for the P atoms. This is because P likes to be hypervalent and use its low lying d orbitals and this has not been previously accounted for. In order to include these orbitals the gaussian input file was edited manually the keyword "extra basis" was added and the following was added at the end of the file:

(blank line) P 0 D 1 1.0 0.55 0.100D+01 **** (blank line)

The file was submitted to the scan and the results are shown below.

Before the third optimization a lower energy structure had been found for the cis isomer, however the results of the third optimization show the reverse. The trans isomer now has a lower energy by about 3 kjmol-1, this energy is small and in agreement with literature which reports the trans isomer to be the more stable isomer. However the difference in the energies falls well within the limits for error in the calculations and cannot be used as conclusive evidence. The relative ordering of the cis and trans isomer could be controlled by controlling the substituents on the P atoms. It could be controlled with steric or electronic effects. If large bulky ligands were used the lowest energy structure would be when they were as far apart as possible, the trans isomer. Changing the electron withdrawing or donating properties of the ligands would change the bonding an maybe the orbitals being used and would probably allow some control over the relative stability of each isomer. If these effects could differ the energy of the isomers by enough then this could be observed computational but currently with he molecules being investigated the energy difference between the two is so small after each of the three optimizations that no conclusion can be drawn about the relative stabilities.

Vibrational Analysis

Before any further analysis was carried out a frequency analysis was run to ensure the optimized structure was in fact a minima. No negative frequencies were found indicating that the optimized structure is a true minima. Not all the frequencies are going to be analysed, just the C=O stretching frequencies and the low energy modes. Shown in the table below is the two low frequencies for each of the isomers.

| Cis Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 DOI:10042/to-6600 | Trans Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 DOI:10042/to-6601 | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode | Vibration | Freq./ cm-1 | Intensity | Description | Mode | Vibration | Freq./ cm-1 | Intensity | Description | ||||||

| 1 |

|

12 | 0 | Conrotation of the two Phosphino ligands | 1 |

|

4 | 0 | Rotation of the two phosphino ligands in the same direction while the rest of the molecule rotates the opposite way. | ||||||

| 2 |

|

20 | 0 | Disrotation of the two phosphine ligands. | 2 |

|

7 | 0 | Rotation of the two phosphine ligands in opposite directions. | ||||||

As can be seen above the low frequency modes are due to the rotations of the PCl3 ligands. At room temperature thermal energy is approximately, kBT= 2.5 kjmol-1 which corresponds 207 cm-1 meaning that these low energy vibrations shown above could easily be occurring at room temperature with quite a high intensity. They will occur when two molecules collide and the translational energy is used to create these vibrational excited states, the higher frequency vibrations are unlikely to occur at room temperature as they need specific excitation.

Now the structure has been confirmed to be a minimum a full analysis of the isomers can be carried out. Firstly the geometry will be considered specifically the bond lengths and angles. These calculations yield results where the bond length is accurate to 0.01Å and the bond angles are accurate to 0.1°

| Cis Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 | Trans Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bond | Calc. length/ Å | Lit. length/Å | Bond angle | Calc. angle/o | Lit. angle/o | Bond | Calc. length/Å | Lit. length/Å | Bond angle | Calc. angle/o | Lit. angle/o |

| Mo-P | 2.47 | 2.52 | P-Mo-P | 94.3 | 97.5 | Mo-P | 2.42 | 2.50 | P-Mo-C | 91.6 | 92.0 |

| Mo-C | 2.02 | 2.03 | P-Mo-C | 92.2 | - | Mo-C | 2.06 | 2.01 | C-Mo-C | 90.8 | - |

| P-Cl | 2.12 | - | Cl-P-Cl | 100.2 | - | P-Cl | 2.12 | 1.84 | Cl-P-Cl | 100.2 | - |

| C=O | 1.17 | - | C-Mo-C | 87.0 | 92.1 | C=O | 1.17 | 1.16 | - | - | - |

The important bond lengths and angles are shown in this table and literature value are shown when they could be found. The exact same complex was found for the trans[3]isomer however the cis isomer[4] could only be found with methyl groups on the phosphine rather than phenyl's, this difference is small however and should still give a good indication of the accuracy of the calculation. In the cis and trans isomer the bond lengths are very similar to those found in literature as are the MO-C bonds and the C=O bonds. The only significant difference is that of the the P-Cl bonds which are P-Ph bonds in literature, therefore the difference is expected. The bond length of Mo-C in the cis complex is reported above to be 2.02 Å, this is in fact the length of the equatorial Mo-C bonds and the axial Mo-C bonds are slightly longer having the value of 2.05 Å. When comparing two bonds between the same atoms a shorter bond indicates a stronger bond, therefore here the equatorial bonds are slightly weaker than the axial bonds this be be credited to the relative trans effect of the two ligands. CO has a stronger trans effect so competition for electron density is larger and a CO ligand is trans to another CO ligand the bond is weaker as they both compete equally for electron density. Where as when the CO ligand is trans to the P ligand there is less competition for electron density and therefore the bond is shorter and stronger.

CO frequencies

The next thing to be analysed is the C=O stretching frequencies to see if the prediction about how the symmetry of the molecule affect the number of C=O stretching frequencies is correct and in agreement with literature.

| Cis Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 | Trans Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency/cm-1 | Intensity | Symmetry | Literature[5] Freq. Mo(CO)4PCl3 | Literature[2] Freq. Mo(CO)4PPh3 | Frequency/cm-1 | Intensity | Symmetry | Literature[4] Freq. Mo(CO)4PCl3 | Literature[2] Freq. Mo(CO)4PPh3 |

| 1938 | 1604 | B2 | 1986 | 1897 | 1939 | 1606 | Eu | 1896 | 1902 |

| 1941 | 813 | B1 | 1994 | 1908 | 1939 | 1606 | Eu | 1896 | 1908 |

| 1952 | 588 | A1 | 2004 | 1927 | 1966 | 5.9 | B1g | - | - |

| 2019 | 545 | A1 | 2072 | 2023 | 2025 | 5.4 | A1g | - | - |

The first point to note is that all the calculated frequencies are lower then the literature values given for both complexes. This implies that the bonds in the optimized geometry structure are weaker than the true structures, however the error in each frequency seems to be fairly consistent indicated with it being lower by about 50 cm-1 each time. So the differences may be due to a systematic error in the calculation rather than the structure of the calculated molecule. It is generally assumed that there is about a 10% error in the calculated values this error is beacuse the gaussian is calulated the frequencies it takes an atom in its relaxed structure and moves it slightly to the right and then slightly to the right to obtain harmonic curve and the frequency is calculated from the curvature of this harmonic curve (harmonic curve are symmetric about the relaxed structure point). However in reality vibrations are anharmonic whcih means that the curve is not symmetric about the minimum point and this differecne results in errors in the calculations. As expected the cis isomer demonstrates 4 stretching frequency's. The calculated trans isomer stretching frequency's are a little harder to interpret, 4 calculated frequency's are shown in the table above two of which have the same symmetry these are due to the antisymmetric stretch of the C=O ligands which are trans to each other, there are frequency's because there are two sets of trans C=O ligands. These two vibrations are degenerate and will appear as one on the IR spectrum. Two more frequencies are calculated for the trans isomer one is due to the symmetric stretch of the trans C=O ligands and other is from the symmetric stretch of all the C=O ligands at the same time. Neither of these stretches change the dipole moment of the molecule and the fact that they appear here indicates that the symmetry is not perfect and these stretches do induce a change in the dipole moment of the molecule. This is most likely true in the experimental values as well but as the intensity is so small they are difficult to observe.

Mini Project

Introduction

Phosphazenes are a group of compounds containing a phosphorus-nitrogen double bond, there are many well established chain, ring and cage phosphazene compounds. Here the inorganic phosphazene heterocycle (PNX2)3 will be investigated, it has been reported that this cyclic trimer has a planer six-membered ring structure in which all the P-N bond lengths are equal and shorter than a normal P-N bond. These facts will be investigated along with an molecular orbital analysis in an attempt to observe the proposed aromatic delocalised bonding. Furthermore an NBO analysis will be carried out in an attempt to understand the nature of the delocalised bonding in terms of which atoms and orbitals contribute most significantly. The substituents on the P atom will be varied to X= F, Cl, Br and OH and the effect on the P-N bond lengths, frequency and bonding will be analysed.

Optimization

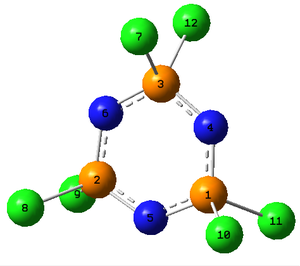

Firstly each of the four molecules were drawn in gaussview, to ensure the π bonding in the ring was delocalised a benzene ring was drawn and the carbons replaced with P and N atoms. The valency of Phosphorus was increased so that the substituents could be added and the first optimization was carried out. The method used was DFT/B3LYP and the low level basis set and associated psedo poteintial LANL2MB was used, the keywords "opt=loose" was also added to reduce the accuracy of the convergence to match the inaccurate basis set being used. This first optimization was carried out just to obtain a rough idea of the optimized structure and will greatly reduce the time and computational power needed for the later optimizations. As can be seen below the first optimization returned a planer rings with equal bond lengths and single bonds around the ring, the bonds to the Br are not drawn and the ring appears to be slightly misshapen. A second optimization was then carried out using the more accurate basis set and pseudo potential LANL2DZ the convergence criteria was also tightened by adding the key words "int=ultrafine scf=conver=9", this tightens the step sizes and cutoffs on the forces that are used to determine the convergence. This second optimization returned structures where the bonding around the ring consists of a single bond and also a dashed bond, which represents delocalised bonding similar to that of benzene, still the bonds to the Br atoms are not drawn. It is thought that while the σ framework of the ring is made up from p and s orbitals the delocalised bonding i.e the π interations are due to overlap of the Nitrogen p orbitals and the Phosphorus d orbitals, and so far in these calculations only a minimal basis set has been used. Therefore the third and final optimization will be carried out accounting for the P d orbitals, this optimization was run as the second but adding the keyword "extrabasis" and the input file was edited to add these d functions. This optimization returned a structure with bonds now drawn from the P atoms to the Br atoms and each of the bonds around the ring now appears as a full double bond. The NBO analysis of these bonds will be carried out later. Below is shown the structure of each molecule after each optimization to show the gradually changing structure of each optimization. π σ*

| 1st DOI:10042/to-6653 | 2nd DOI:10042/to-6654 | 3rd DOI:10042/to-6655 | |||||||||

|

|

|

| 1st DOI:10042/to-6652 | 2nd DOI:10042/to-6656 | 3rd DOI:10042/to-6657 | |||||||||

|

|

|

| 1st DOI:10042/to-6658 | 2nd DOI:10042/to-6659 | 3rd DOI:10042/to-6660 | |||||||||

|

|

|

| 1st DOI:10042/to-6663 | 2nd DOI:10042/to-6662 | 3rd DOI:10042/to-6661 | |||||||||

|

|

|

To confirm each structure was in fact a minimum, a frequency calculation was run on each of the final structures, each one returned all positive frequencies with close to zero low frequencies indicating that each the optimized structure for each molecule found was a minimum.

Bond lengths

To see if the structures obtained were sensible the bond lengths are compared to those found in literature. Also to see if including the d orbitals had an effect on the geometrical parameter of the bond length. The results are shown below.

| Molecule | Bond | 2nd optimization no d functions bond length/ű0.01Š| 3rd optimization including d functions bond length/ű0.01Š| Literature[6][7] [8] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (PNF2)3 | P-N | 1.67 | 1.58 | 1.57 |

| (PNCl2)3 | P-N | 1.68 | 1.59 | 1.59 |

| (PNBr2)3 | P-N | 1.69 | 1.60 | 1.60 |

| (PNOH2)3 | P-N | 1.68 | 1.59 | - |

| (PNF2)3 | P-F | 1.67 | 1.57 | 1.52 |

| (PNCl2)3 | P-Cl | 2.21 | 2.06 | 1.99 |

| (PNBr2)3 | P-Br | 2.41 | 2.27 | 2.20 |

| (PNOH2)3 | P-O | 1.70 | 1.61 | - |

The first thing to mention is the difference in the cyclic phosphazene P-N bond lengths (around 1.58 angstroms) to the bond lengths in linear phosphazenes which are reported to be in the region of 1.77 Å[9], this indicates that the cyclic phosphazenes are some way stabilised compared to the linear phosphazenes. Secondly only one P-N bond length is reported above for each of the the molecules this is because all the P-N bonds were found to be equal and in agreement with literature. This indicates the presence of delocalised bonding around the ring. In order for this stabilisation and delocalised bonding to understood the electronic structure of the molecules will need to be solved and analysed this will be carried out later. The third optimization yielding a geometry in excellent agreement with literature for the P-N bonds with the exact values being calculated within the error of the the calculation ±0.01Å . Without the d orbitals being included in the optimization it can be seen that the same trend is observed but the values are much further than literature, therefore it was important to include the d orbitals of Phosphorus to obtain an accurate structure.

The phosphazene with the most electronegative substituent (F) has the shortest P-N bond distances and as the electronegativity of the halogens decreases the P-N bond gets longer. The OH substituent also fits well with this scale as oxygen's electronegativity sits between that of F and Cl and the P-N bond length in the OH compound is found to be the same as the Cl compound. This strengthening of the bond can be put down to three things, firstly as the electronegativity of the substituent increases electron density is drawn away from the P atoms and this facilitates donation of a lone pair on N to the P atoms and hence strengthening the P-N bond. Secondly it is known that electron withdrawing substituents cause d orbitals to contract and in doing so this would allow more efficient overlap between the p and d orbitals that are thought to contribute to the delocalised bonding around the ring. Thirdly it is thought that if the substituent as well as being electronegative can also donate a lone pair then it is possible that this lone pair could donate into the π* orbital of the ring an hence reduce the bond order. For any of these explanations to be confirmed a full molecular orbital and NBO analysis needs to be carried out.

The P-X bond to the substituents can be understood by considering the size of each of the substituents, and the calculated bond lengths fit relatively well when compared to the sum of the covalent radii and to that of literature where the values could be found. The possiblilty of exocyclic double bond character has been mentioned earlier as donation of a lone pair on the substituent into the π* orbital of the P-N bonds. It is possibly to gauge if this is happening by considering the length of the P-X bond, in the OH molecule the P-O bond is 1.61 angstroms which according to this literature article[10] corresponds to a bond order between 1.2 and 1.3 suggesting that there is some π character in the P-O bonds.

| Molecule | Angle | 2nd optimization no d functions bond angle/o±0.1o | 3rd optimization including d functions bond angle/o±0.1o | Literature[6][7] [8] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (PNF2)3 | P-N-P | 122.1 | 125.5 | - |

| (PNCl2)3 | P-N-P | 123.0 | 125.8 | 121.2 |

| (PNBr2)3 | P-N-P | 123.8 | 126.3 | 126.8 |

| (PNOH2)3 | P-N-P | 121.5 | 124.5 | - |

| (PNF2)3 | N-P-N | 117.9 | 114.5 | - |

| (PNCl2)3 | N-P-N | 117.0 | 114.2 | 118.5 |

| (PNBr2)3 | N-P-N | 116.2 | 113.7 | 118.3 |

| (PNOH2)3 | N-P-N | 118.7 | 113.5 | - |

| (PNF2)3 | F-P-F | 97.1 | 98.9 | - |

| (PNCl2)3 | Cl-P-Cl | 100.8 | 102.4 | 108.6 |

| (PNBr2)3 | Br-P-Br | 102.1 | 103.5 | 103.4 |

| (PNOH2)3 | OH-P-OH | 103.1 | 99.2 | - |

The exocyclic bond angle between P and the two substituents on it increases as the subtituent size increases as expected with steric restrictions. The endocyclic angle at N is found to larger than that at P which is an agreement with literature and will be hopefully understood after the NBO analysis is carried out and the relative contributions to the cyclic bonds is established.

Frequency Analysis

As well as confirming the presence of a minimum the data from the frequency calculations can be used to compare to that in literature and confirm the relative strength of the P-N cyclic bonds.

| Molecule | Computed frequency /cm-1 | Lit.[11] stretching frequency /cm-1 | Link to frequency calculation file |

|---|---|---|---|

| (PNF2)3 | 1337 | 1297 | DOI:10042/to-6943 |

| (PNCl2)3 | 1268 | 1218 | DOI:10042/to-6944 |

| (PNBr2)3 | 1240 | 1175 | DOI:10042/to-6945 |

| (PNOH2)3 | 1286, 1304 | - | DOI:10042/to-6946 |

The highest intensity vibrations were observed in the region on 1200/1300cm-1, these correspond to the P-N-P stretching mode which is degenerate and it is this frequency that is reported in the table above. There is also a degenerate P-N-P stretching mode around 800 cm-1 however the intensity was much lower as the stretch is symmetric and therefore not IR active. These stretches when the substituent is OH are not degenerate due to the reduced symmetry of the molecule. As expected the highest frequency occurs for the compound with F substituents supporting the explanation earlier that it is in this molecule that the P-N bonds are strongest. The trend in stretching frequency follows that of the bond length and hence both can be credited to the relative bond strength in each of the molecules. The difference in the frequencies from literature is expected as a harmonic approximation has been used for vibrations that are actually anharmonic, however the calculated trends and the trend observed in literature are very similar.

MO analysis

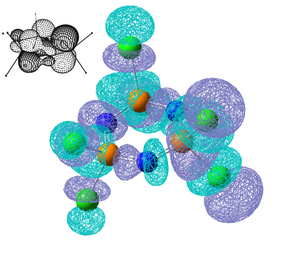

Classically the π bonding in cyclic phosphazenes was thought to consist of two d orbitals from the P atoms and one p orbital from a N atom to form a weakly interacting three centre π bond with the N atom being in the middle and the location of high electron density with nodes at the P atoms. This is known as Dewar's three-center island model[12] and implies that due to the disruption of conjugation at the P atoms that the compounds were not aromatic and therefore don't need to be planer. This explanation is often invoked to explain the apparent hypervalent P atoms in such compounds. However theoretical studies[13] have indicated that d functions actually only play a minor role acting mainly as polarization functions and the structure is better represented by a cyclic system contained highly polarised P-N bonds. The NBO analysis will hopefully elude which orbitals form the delocalised bonding, but first the molecular orbitals will be considered. Shown below is the Molecular orbital diagram of (NPF2)[14]which has been constructed from a N33- fragment and a (PF2)33- fragment and the point group of the molecule is assumed to be D3h

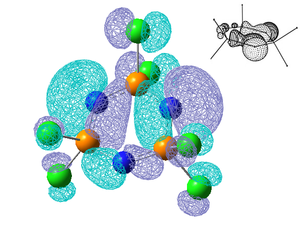

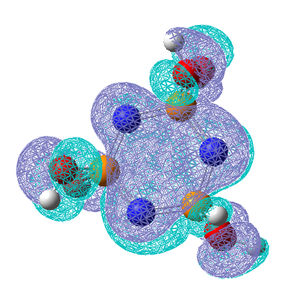

Shown below are the 5 highest energy computed occupied molecular orbitals, they correspond well to the orbitals shown in the above MO diagram and the corresponding molecular orbitals are shown alongside. The computed ordering of the degenerate molecular orbitals is slightly different to that in the molecular orbital diagram as they are very close in energy. MO35 is a pi-axial 6 centred bond as the molecular orbital is spread across all the cyclic atoms in disagreement with Dewars[12] 'island' theroy. MO's 36-39 shown significantly more electron density on the N atoms and are considered as lone pairs on the N atoms. It is important to notice that the d orbitals on P don't appear to contribute to the molecular orbitals and the π bonds are formed predominantly from the p orbitals on the N atoms.

|

|

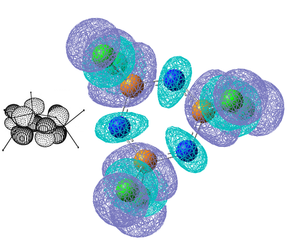

Next is shown the 3 lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals, these orbitals have either non-bonding or anti-bonding P-N character. Another thing to note is the large HOMO-LUMO gap compared to the difference in energy between the occupied orbitals, the occupied orbitals energy that are shown above range from -0.35 to -0.33 and then the LUMO has an energy of -0.07 which is still stabilised as the energy is negative, but much less stabilised than the occupied orbitals.

|

|

|

NBO Analysis

Below is summarised to NBO analysis for (NPCl2)3, only four bonds are shown as all the others are equivalent to these four. It can be seen that the bonds that make up the sigma framework of the ring come from predominantly the N atoms, they contribute 70% to the bonds and are approximately sp2 hybridised. A double bond is observed between alternating P-N bonds and is made up almost entirely from a p orbital on the N atoms. Immediately it can be seen that despite the d orbitals contributing 43% to the hybridised orbital on the P that takes part in this bond, the contribution to these double bonds from the P atoms is so small that the contribution from the d orbitals on the P atoms is insignificant. Instead these double bonds which represent the delocalised bonding come almost entirely from the p orbital on the N atoms. In the P-Cl bond the d orbitals contribute slightly more but the bonding is predominantly from a p orbital on the Cl atoms. The NBO calculations were run on the other three molecules, the σ P-N bond in each was found to be very similar with the relative contributions from the P and N atoms and the orbitals within these not varying significantly. However as shown below it was found that there was a second bond between alternate P-N bonds, this only occurred in the Cl and F complexes where as in the Br an OH complexes no double bonds were observed.

| NBO | Occupancy | % Contribution from each atom | % Hybridisation of P | % Hybridisation of N (Cl) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | N | s | p | d | s | p | ||

| P1-N4 single bond | 1.97 | 26 | 73 | 30 | 68 | 2 | 40 | 60 |

| P1-N5 single bond | 1.97 | 26 | 73 | 30 | 68 | 2 | 40 | 60 |

| P1-N5 double bond | 1.80 | 8 | 91 | 0 | 56 | 43 | 0 | 100 |

| P1-Cl10 single bond | 1.84 | 30 | 70 | 20 | 50 | 30 | 13 | 86 |

There are two proposed explanations for the π bonding, the first has been discussed earlier and is thought to be due to overlap between the p orbitals on N and d orbitals with π symmetry to form a delocalised cyclic system. The second is that the π bonding around the ring is due to the the p lone pair on the N atom (as previously established) donating into a highly polarised σ* P-X bond on the adjacent P atom, this effect is know as negative conjugation[15]. If the second explanation is the case then the fact the P-N bond is shortest when the substituent is F can be easily explained, the σ* P-F bond will be lowest in energy due to the highly electronegative character of the F atom and the overlap between the the p orbital on the N atom and this σ* orbitals will be much better allowing a stronger and shorter bond to be formed. This effect can be seen in the relative bond length and stretching frequencies as discussed earlier, it can also be seen when looking at the % contribution to the double bond from each atom, when Cl is the substituent the contribution from the N atom is 91% then on changing the substituent to F the contribution from N increases to 93% as the overlap is now better. In order to confirm either bonding mode is occurring more data needs to be extracted from the output file of the NBO calculations.

In the OH and Br molecules there are two lone pairs on the nitrogen atom (one p and one sp2) as opposed to one lone pair (sp2) as seen for the other molecules, demonstrated that it is the p orbital lone pair which contributes significantly the double bonds when they are present. However in the Br and OH molecules where there are two lone pairs, the occupancy of the p lone pair is significantly lower than that of the sp2 lone pair (1.64 for the Br molecule and 1.73 for the OH molecule), indicating that despite the output file saying there is no double bonds the N p orbital lone pair is still donating some of its electron density to create some double bond character but not enough electron density is found between the two atoms for it to be considered a double bond. Therefore where this electron density is being donated is what will provide information about the nature of the delocalised bonding. The occupancy of the P-Br(OH) sigma* bonds are found to be 0.24 (0.17) which is relatively high for an anti-bond, it is therefore possible that some of the electron density that is 'missing' from the p orbital lone pair is located in this antibond but the interaction is not considered high enough to be a second bond.

Furthermore it was noticed that even the occupancy of the P-N sigma antibonds were higher than expected for what is usually considered as an unoccupied orbital. The occupancy was found to be in the region on 0.1-0.2 for all of the molecules. Also the occupancy of the sp2 lone pair on nitrogen is also not that close to the ideal value of two, and all the molecules had an occupancy of 1.8 for this lone pair. So again like before it is possible that it is the lone pair donating into the anti bonding orbitals of appropriate symmetry. It is thought that the spatial overlap for this in plane interaction is particularly good. This interaction is however smaller and is not large enough in any of the molecules to be considered as a actual bond. This is perhaps the only place that the d orbitals play a significant role in the bonding of the molecules as both the P-R and P-N antibond have significant d character.

The above observations indicative that it negative hyperconjugation occurring producing some delocalised bonding around the ring. This negative hyperconjugation can be confirmed by the low occupancy or lack of the p lone pair on the N atom, insignificant contribution from the d orbitals to any of the bonds in the molecules and the unusually high occupancy of the σ* P-N and P-R bonds. Furthermore this negative hyperconjugation effect is also seen to vary greatly when the substituent is varied, with negative hyperconjugation being most efficient when the substituents are electronegative. Therefore the source of delocalised bonding in the molecules can be credited not to the overlap lap of p orbitals with P d orbitals. Although, this overlap is not symmetry forbidden and the orbitals are probably not that different in energy due to the d orbitals contracting due to the highly electronegative substituents. The delocalised bonding can instead be credited to electron pairs lying predominantly on the N atoms donating there electron density into antibonding orbitals, leading to multiple bonding character due to negative hyperconjugation. The important data that was extracted from the log files to reach these conclusions is summarised in the table below.

| Molecule | Occupancy of p orbital LP on N | Occupancy of P-R sigma* | Occupancy of sp2 orbital LP on N | Occupancy of P-N sigma* |

| (NPF2)3 | NA | 0.11 | 1.82 | 0.10 |

| (NPCl2)3 | NA | 0.15 | 1.81 | 0.14 |

| (NPBr2)3 | 1.67 | 0.23 | 1.81 | 0.14 |

| (NPOH2)3 | 1.73 | 0.17 | 1.82 | 0.10 |

As the d orbitals have not been calculated to take part significantly in the bonding around the ring, the possibility of not using them in the calculations may seem possible but as seen earlier including the d orbitals gave much more accurate structures. The d orbitals are necessary as they act as polarization functions to polarize the p functions and allow and accurate representation of the bonding to be established here, this is particularly important here due to the highly polar nature of the P-N bonds around the ring. The necessity of including these d orbitals means that despite the above evidence the participation of the d orbitals in the delocalised bonding cannot be be disproved.

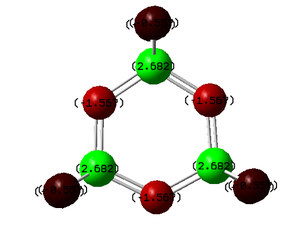

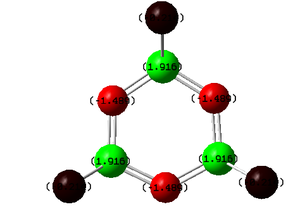

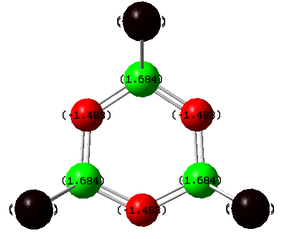

The σ P-N bonds are highly polarised and the shortening of the bonds as well as being due to the delocalised bonding could be due to the bond contracting due to electrostatic interactions and the bond may have a certain amount of ionic character. It can be seen from the NBO analysis that both the σ and π bonds around the ring are predominantly from the N atoms. A nice comparison between the extent of delcoalised π bonding formed the nitrogen lone pairs and the substituent on P can be seen by comparing the molecular orbitals for the 6 centred π-axial bond, shown as MO35 above, the analogous MO's for (NPF2)3, (NPBr2)3 amd (NPOH2)3 are shown below along with the NBO charges for each molecule. To clarify these molecular orbitals are not the Homo's as the Homo's are the sp2 lone pairs on the N atoms, these orbitals are the highest occupied molecular orbitals which do not represent the N lone pairs, they represent the 6 centred pi-axial bond which is one of the molecular orbitals which shows the delocalised bonding around the ring.

| (NPF2)3 DOI:10042/to-6777 | (NPCl2)3 DOI:10042/to-6664 | (NPBr2)3DOI:10042/to-6778 | (NPOH2)3DOI:10042/to-6779 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

All previous data has demonstrated that the the P-N bonds in the phosphazene with the most electronegative substituent have the most double bond character (which when is between every other bond can be considered as a delocalised system). The MO for the F molecule is the most delocalised around the ring and and has the most density on the P atoms, the MO is spread across the top and bottom face of the ring with no hole in the middle like the others. This kind of molecular orbital is what is expected in an aromatic molecule therefore when the substituent is F the molecule can be considered to have some aromatic character. As the substituent becomes less electronegative the MO becomes less diffuse and as can be seen when the substituent is Br, hardly any density is observed on the P atom, this is expected as no double bond was reported in the NBO data and the electron density on the N atom is much higher. Just looking at these molecular orbitals it might be expected that double bonds would be observed when the the substituent is OH as the MO looks similar to that of that of the Cl molecule however it is possible that the high electron donating properties of OH have some effect on the double bonds. The MO of the OH molecule appears slightly skewed and not as symmetrical as the others this is because the molecule is less symmetrical due to the OH substituents. In order to see if the high electron donating property of OH affected the electronic structure of the molecule, lower occupied MO's were looked out, and the below MO was found for the OH molecule but no analogous one for any of the others.This MO is the next lowest in energy after the pi axial MO, and clearly demonstrates the OH interacting with the N atoms on either side of it. This interaction is most likely to be a lone pair on the Oxygen atom donating into the into the π* orbital of the P-N bond (if such bond exists), this interaction could be another reason why no double bond is reported in this molecule.

It was hoped that the NBO charges may show the same trend as the MO's with the negative charge increasing (positive charge decreasing) on the P atoms as the the pi bonding become more delocalised, however as can be seen above this is not the case and the positive charge increases on the P atoms as the bonding becomes more delocalised. This is because this molecular orbitals is not the only thing affecting the charge in the molecule, the overriding factor is the elctronegativity of the substituents, the more electronegative the more negative charge is withdrawn from the P atoms leaving the P atoms more positive when the π bonding is more delocalised( but it is not a result of this). In contrast the charge on the N atoms doesn't vary very much reflecting the similarity of the P-N sigma bonds.

Secondry order interactions

The final thing to be considered is the secondary orbital interactions to see if there are any significant interactions from bonding NBOs into antibonding NBOs. Such interactions were found for the molecules with the substituents F and Cl. The donor NBO is the σ bond between the P and F(Cl) and the acceptor is the π* orbital of the P-N double bonds, the E2 interaction energy is 75 kcal/mol for Cl and 42 kcal/mol for the F molecule. The sigma P-X bond is predominantly X in character and almost all p orbital therefore this interaction can be considered as a lone pair on the halogen atom donating into the π* orbital of the P-N double bonds, there are six of these interactions present one for each of the halogen atoms. As before this interaction can be seen by looking at the occupancy of the lone pairs on the substituent atoms and the π bond (where present), the occupancy of this antibonding orbital will confirm this interaction. This data is given below.

| Molecule | Occupancy of LP on substituent | Occupancy of P-X π* |

| (NPF2)3 | 1.94 | 0.18 |

| (NPCl2)3 | 1.93 | 0.29 |

| (NPBr2)3 | 1.94 | NA |

| (NPOH2)3 | 1.92 | NA |

As expected the occupancy of the lone pair is less than the ideal value of two and the occupancy of the pi* orbitals is higher than zero confirming that there must be some kind of donation into these orbitals. The larger interaction energy seen in the Cl molecule is also obvious from the occupancy numbers, as the occupancy of the Cl π* orbital is significantly higher than that of the F molecules π* orbital. This can put down to F being more electronegative and therefore its lone pairs are held tighter and donation occurs less easily.

There is another interaction present in these molecules between the σ P-F bond into the P-F σ* bond of the other halogen bond on the same P atoms. Again there are six of these interactions and will the value of 25 kcal/mol for the F molecule and 42 kcal/mol for the Cl molecule.

Conclusion

Optimizing the geometry of the structures yielded results similar to that of literature with the inclusion of d orbitals in the calculations found to be of great importance. The computed MO's correspond to the molecular orbitals obtained in the qualitative LCAO approach. Most importantly the NBO analysis showed that the organic aromaticity concept cannot be used to describe the bonding in these molecules. The bonding can be described as follows; the sigma framework is built up form highly polarized P-N bonds probably having a large amount of ionic character, the N atoms are sp2 hybridised with the remaining p orbital lying perpendicular to the plane of the ring containing a lone pair. The P atoms are somewhere between sp2 and sp3 hybridised with two σ bonded substituents on each atom, these bonds are skewed towards the substituent with the P atom contributing the most when the substituent is less electronegative. The delocalised bonding of the cyclic system is credited to two interactions, the first between the sp2 lone pair on each N atom into the P-X σ* orbitals and the second from the in plane sp2 lone pair into the σ* P-N orbitals. When the elctronegativity of the substituents is high enough then the first interaction is larger due to the lower energy antibonding orbitals, where as the second interaction doesn't vary between each molecule. If these two interactions are large enough and there is enough electron density between the P and N atoms this is reported as a double bond, as is the case in the Cl and F molecules. Establishing the nature of the delocalised bonding allows the trends in the bond lengths and stretching frequencies to be justified, as the the electronegativity of the substituents increases the donation from the N atoms increases and the π bonding spreads across the whole molecule as it would in an aromatic structure, this effect can be seen earlier in comparing the π axial MO's of each of the molecules. In turn this increase in delocalised bonding results in a decrease in P-N bond length and an increase in the P-N stretching frequency. Calculation of the nucleus independent chemical shift values would have been a nice extension to this project as the chemcial shift of the P and N atoms would have provided information about the size of the ring current and hence the delocalization around the ring.

References

- ↑ M.R. Bernejo et al., Polyhedron, 1988, 7, 2561-2567 DOI:10.1016/S0277-5387(00)83874-7

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 D. J. Darensbourg and R. L. Kemp, Inorg. Chem, 1978, 17, 2680. DOI:10.1021/ic50187a062

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 G. Hogarth, lnorganica Chimica Acta, 254,1997, 167-171 DOI:10.1016/S0020-1693(96)05133-X

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 F. Cotton, Inorg. Chem. 1982, 21, 2661-2666

- ↑ ELmer C. Alyea and Shuquan Song, Inorg. Chem., 1995 34, 3864-3873 DOI:10.1021/ic00119a006

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 G.J. Bullen, J. Chem. Soc, 1971,1450 DOI:10.1039/J19710001450

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 W. M. Doughill, J. Chem. Soc, 1963, 3211

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 E. Giglio. R. Puliti, Acta. Cryst,22 1967, 304

- ↑ E. Hobbs, D. E. C. Corbridge, and B. Raistrick, Acta Crystallogr., 1953, (6), 621

- ↑ E. A. Robinson, Canadian Journal of Chemistry, 1963, 3021

- ↑ H. R. Allock Chem. Rev, 1972, 72, 315 DOI:10.1021/cr60278a002

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 M. J. S. Dewar., E.A.C. Lucken., M.A. Whitehead., J. Chem. Soc, 1960, 2423

- ↑ R. C. Haddon., Chem. Phys. Lett., 1985, 120, 372

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 L. Kapicka., P. Holb., J. Mol. Struc, Theochem, 2007, 820, 148

- ↑ A.B. Chaplin, J.A. Harrison, P.J. Dyson., Inorg. Chem., 1986, 108