Rep:Mod:lks11mp

Larissa See

CID: 00684162

BSc Chemistry

3rd Year Inorganic Computational Lab

Introduction

Ionic liquids are ionic compounds that have low melting points and hence, exist as a liquid at room temperature. The prospect of using them as solvents is attractive as their properties can be tuned by altering the anion and cations used, as well as modifying the R groups on them. However, this also results in an extremely wide range of possible combinations of ions, making it virtually impossible to test the properties of each one of them to determine their properties and examine their potential. As such, computational chemistry provides an alternative method of doing this by enabling the properties of the ions to be predicted and compared more efficiently before synthesising and testing them.

Part 1: Comparison of 'onium' cations

Optimisation

Optimisation on all compounds were done using 3‑21G first, followed by 6‑31G (d,p). The "nosymm" keyword was used in all calculations.

[N(CH3)4]+

The log file for [N(CH3)4]+ optimisation can be found here

The D-space link can be found here

Summary of calculation details

File type: .log

Calculation type: FOPT

Calculation method: RB3LYP

Basis set: 6‑31G (d,p)

Charge: 1

Spin: Singlet

Final energy: ‑214.18127322 a.u.

Gradient: 0.00000010 a.u.

Dipole moment: 1.87 Debye

Point group: C1

Time taken for calculation: 8 min 55.2 s

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000000 0.000002 YES

RMS Force 0.000000 0.000001 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000004 0.000006 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000001 0.000004 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-5.867891D-13

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

The calculations are complete as the forces and displacement have converged.

[P(CH3)4]+

The log file for [P(CH3)4]+ optimisation can be found here

The D-space link can be found here

Summary of calculation details

File type: .log

Calculation type: FOPT

Calculation method: RB3LYP

Basis set: 6‑31G (d,p)

Charge: 1

Spin: Singlet

Final energy: ‑500.82701172 a.u.

Gradient: 0.00000049 a.u.

Dipole moment: 1.97 Debye

Point group: C1

Time taken for calculation: 11 min 31.6 s

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000000 0.000002 YES

RMS Force 0.000000 0.000001 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000001 0.000006 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000001 0.000004 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-7.887038D-14

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

The calculations are complete as the forces and displacement have converged.

[S(CH3)3]+

The log file for [S(CH3)3]+ optimisation can be found here

The D-space link can be found here

Summary of calculation details

File type: .log

Calculation type: FOPT

Calculation method: RB3LYP

Basis set: 6‑31G (d,p)

Charge: 1

Spin: Singlet

Final energy: ‑517.68327451 a.u.

Gradient: 0.00000039 a.u.

Dipole moment: 4.85 Debye

Point group: C1

Time taken for calculation: 6 min 18.2 s

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000000 0.000002 YES

RMS Force 0.000000 0.000001 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000004 0.000006 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000001 0.000004 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-2.079335D-13

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

The calculations are complete as the forces and displacement have converged.

Frequency Analysis

[N(CH3)4]+

The log file for [N(CH3)4]+ frequency analysis can be found here

The D-space link can be found here

Summary of calculation details

File type: .log

Calculation type: FOPT

Calculation method: RB3LYP

Basis set: 6‑31G (d,p)

Charge: 1

Spin: Singlet

Final energy: ‑214.18127322 a.u.

Gradient: 0.00000025 a.u.

Dipole moment: 1.87 Debye

Point group: C1

Time taken for calculation: 17 min 44.5 s

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000001 0.000002 YES

RMS Force 0.000000 0.000001 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000003 0.000006 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000001 0.000004 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-2.549655D-12

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

Low frequencies --- -5.4439 -2.1088 -0.0004 0.0006 0.0006 4.0170 Low frequencies --- 183.7606 288.3973 288.8973

The low frequencies obtained are between ±15 cm-1. The calculation is complete as the frequencies obtained are positive, showing that a minimum point has been obtained.

[P(CH3)4]+

The log file for [P(CH3)4]+ frequency analysis can be found here

The D-space link can be found here

Summary of calculation details

File type: .log

Calculation type: FOPT

Calculation method: RB3LYP

Basis set: 6‑31G (d,p)

Charge: 1

Spin: Singlet

Final energy: ‑500.82701172 a.u.

Gradient: 0.00000054 a.u.

Dipole moment: 1.97 Debye

Point group: C1

Time taken for calculation: 17 min 31.7 s

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000001 0.000002 YES

RMS Force 0.000000 0.000001 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000003 0.000006 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000001 0.000004 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.915278D-12

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

Low frequencies --- -2.5541 0.0013 0.0018 0.0023 5.1184 7.5830 Low frequencies --- 156.4501 192.0518 192.2798

The low frequencies obtained are between ±15 cm-1. The calculation is complete as the frequencies obtained are positive, showing that a minimum point has been obtained.

[S(CH3)3]+

The log file for [S(CH3)3]+ frequency analysis can be found here

The D-space link can be found here

Summary of calculation details

File type: .log

Calculation type: FOPT

Calculation method: RB3LYP

Basis set: 6‑31G (d,p)

Charge: 1

Spin: Singlet

Final energy: ‑517.68327451 a.u.

Gradient: 0.00000044 a.u.

Dipole moment: 4.85 Debye

Point group: C1

Time taken for calculation: 8 min 54.1 s

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000001 0.000002 YES

RMS Force 0.000000 0.000001 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000004 0.000006 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000001 0.000004 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.377434D-12

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

Low frequencies --- -7.5683 -0.6431 -0.0027 -0.0023 0.0035 7.2962 Low frequencies --- 161.8565 199.5042 200.0026

The low frequencies obtained are between ±15 cm-1. The calculation is complete as the frequencies obtained are positive, showing that a minimum point has been obtained.

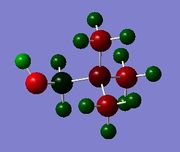

Geometries

The geometry with respect to the central heteroatom is reported in Table 1, with bond distance representing the C‑X bond distance and bond angle representing the C‑X‑C bond angle.

| Compound | Bond Distance (Å) | Bond Angle (°) |

|---|---|---|

| [N(CH3)4]+ | 1.51 | 109.5 |

| [P(CH3)4]+ | 1.82 | 109.5 |

| [S(CH3)3]+ | 1.82 | 102.7 |

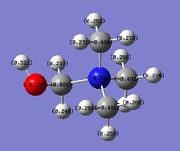

The overall structure of [N(CH3)4]+ and [P(CH3)4]+ are the same and are both tetrahedral with respect to the central heteroatom, with four methyl groups attached to it. This is expected as both are in group 15 and hence, their corresponding 'onium' ions have 4 R groups. Both have no lone pairs and result in tetrahedral geometry. [S(CH3)3]+ has three methyl groups attached to the central sulphur atom and has a trigonal pyramidal shape. As sulphur is in group 16, its corresponding 'onium' ion has 3 R groups attached to the S atom with one lone pair, resulting in a trigonal pyramidal shape.

Comparing [N(CH3)4]+ and [P(CH3)4]+, [P(CH3)4]+ has a longer C-X bond distance of 1.82 Å as compared to [N(CH3)4]+ (1.51 Å). This is because P had one more electron shell than N, resulting in a larger atomic size. As such, the P‑C bond is longer than the N‑C bond. P and S, on the other hand, are both in the same row of the periodic table and hence, are of similar size, resulting in a very similar C-X bond length in [P(CH3)4]+ and [S(CH3)3]+. Without rounding off, the P-C bond length is slightly shorter, at 1.816 Å as compared to 1.823 Å for the S‑C bond. S has a higher effective nuclear charge resulting from it having one more proton than P while the increase in electron does not contribute much to the shielding. As such, S is more electronegative than P, resulting in a more polar S‑C bond, which is expected to be shorter. However,it is difficult to compare the S‑C and P‑C bond lengths as S has one less methyl group attached to it and has a lone pair on it instead.

[N(CH3)4]+ and [P(CH3)4]+ both have a bond angle of 109.5 °, which is as expected for a molecule of tetrahedral geometry. This angle arises from the methyl groups wanting be as far apart as possible to minimise electronic repulsion between the electrons in the C‑X bonds. In [S(CH3)3]+, taking consideration of the lone pair, the molecule actually has tetrahedral geometry. The presence of the lone pair increases repulsion between the lone pair and the electrons in the other C‑X bonds. As such, the 3 C‑S bonds are compressed, resulting in a smaller bond angle of 102.7 °.

MO

The D-space link for [N(CH3)4]+ MO calculation can be found here

The D-space link for [P(CH3)4]+ MO calculation can be found here

The D-space link for [S(CH3)3]+ MO calculation can be found here

The MOs are arranged from 1 to 5 in the order of highly bonding to highly antibonding.

NBO

Charge Analysis

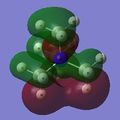

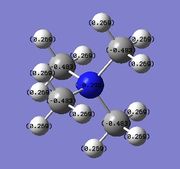

The colour range was set from ‑1.000 to 1.000 for comparison of charges based on colour across all three molecules. The colour range is from bright red, for most negative, to darker red, to darker green, to bright green for most positive.

The electronegativity of N, P and S follows the order N > S > P, with N being much more electronegative than S. Correspondingly, N is negatively charged while P and S are both positively charged. The charge density on these central atoms also follows this trend with N being negatively charged (‑0.295), S being positively charged (0.917), and P being even more positively charged (1.667) than S. Consequently, the C atom of the methyl group bound to N is less negatively charged as N tends to draw more of the electron density towards it. This results in the C atom of the N‑C bond having a charge density of ‑0.483. Following the order of electronegativity (N > S > P), the charge density of the C atom increases with decreasing electronegativty of the heteroatom (‑0.483 for C‑N, ‑0.846 for C‑S, ‑1.060 for C‑P).

Notably, the charge distribution on the H atoms of the methyl group remain relatively similar, ranging from 0.269 to 0.298, and are all positively charged. Following the same order, as electronegativity of the central atom decrease from N to S to P, the C atom becomes more negative, and the H atom becomes more positive (0.269 in [N(CH3)4]+, 0.279 in [S(CH3)3]+, and 0.298 in [P(CH3)4]+.

Applying the charge density obtained from computational calculations to the conventional depiction of NR4+, it is observed that there is a slight discrepancy. The charge distribution on N, though relatively small, is in fact negative (‑0.295). It is more likely that the positive charge is actually spread over the H atoms of the methyl groups as they are shown to have positive charge distribution. By convention, the positive charge on N represents the fact that N has 4 bonds to the alkyl groups and no lone pairs, and therefore, formally has 4 valence electrons. However, based on analysis of the charge distribution, this is unlikely to be a valid description of the actual molecule. By comparison, the positive charge on the central atom is more acceptable in the case of [P(CH3)4]+ and [S(CH3)3]+, where the central P and S atom are positively charged.

Population Analysis

[N(CH3)4]+

(Occupancy) Bond orbital/ Coefficients/ Hybrids

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1. (1.98452) BD ( 1) N 1 - C 2

( 66.35%) 0.8146* N 1 s( 25.00%)p 3.00( 74.97%)d 0.00( 0.03%)

0.0000 0.5000 -0.0007 0.0000 0.3954

-0.0001 -0.7060 0.0001 -0.3080 0.0000

-0.0115 -0.0050 0.0090 -0.0070 -0.0055

( 33.65%) 0.5801* C 2 s( 20.78%)p 3.81( 79.06%)d 0.01( 0.16%)

0.0003 0.4552 -0.0237 0.0026 -0.4056

-0.0172 0.7244 0.0308 0.3160 0.0134

-0.0262 -0.0114 0.0204 -0.0160 -0.0126

[P(CH3)4]+

(Occupancy) Bond orbital/ Coefficients/ Hybrids

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

4. (1.98031) BD ( 1) C 1 - P 17

( 59.57%) 0.7718* C 1 s( 25.24%)p 2.96( 74.67%)d 0.00( 0.08%)

0.0002 0.5021 0.0171 -0.0020 -0.3528

0.0065 0.7051 -0.0129 0.3534 -0.0065

-0.0168 -0.0084 0.0168 -0.0126 -0.0072

( 40.43%) 0.6358* P 17 s( 25.00%)p 2.97( 74.15%)d 0.03( 0.85%)

0.0000 0.0001 0.5000 -0.0008 0.0000

0.0000 0.3515 -0.0005 0.0000 -0.7027

0.0010 0.0000 -0.3522 0.0005 -0.0533

-0.0267 0.0534 -0.0399 -0.0230

[S(CH3)3]+

(Occupancy) Bond orbital/ Coefficients/ Hybrids

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

4. (1.98631) BD ( 1) C 1 - S 13

( 48.67%) 0.6976* C 1 s( 19.71%)p 4.07( 80.16%)d 0.01( 0.14%)

-0.0003 -0.4437 -0.0140 0.0033 0.7017

-0.0055 -0.4206 0.0033 0.3636 0.0098

0.0234 -0.0206 0.0124 -0.0125 0.0096

( 51.33%) 0.7165* S 13 s( 16.95%)p 4.86( 82.42%)d 0.04( 0.63%)

0.0000 -0.0001 -0.4116 0.0075 -0.0012

0.0000 -0.6963 0.0306 0.0000 0.4175

-0.0184 0.0000 -0.4039 -0.0260 0.0436

-0.0532 0.0319 -0.0233 0.0051

21. (1.97343) LP ( 1) S 13 s( 49.14%)p 1.03( 50.85%)d 0.00( 0.01%)

0.0000 -0.0002 0.7010 0.0057 -0.0013

0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

0.0000 0.0000 -0.7121 -0.0364 0.0000

0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 -0.0101

Discussion

| Compound | Bond Contribution (%) | Hybridisation on C (%) | Hybridisation on X (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | X | s | p | s | p | |

| [N(CH3)4]+ | 33.65 | 66.35 | 20.78 | 79.06 | 25.00 | 74.97 |

| [P(CH3)4]+ | 59.57 | 40.43 | 25.24 | 74.67 | 25.00 | 74.15 |

| [S(CH3)3]+ | 48.67 | 51.33 | 19.71 | 80.16 | 16.95 | 82.42 |

With one less electron shell, N is the most electronegative of the 3 central atoms. P and S are in the same row of the periodic table, but S has one more proton than P, resulting in S having slightly strongly effective nuclear charge. This leads to S being slightly more electronegative than P. The electronegativity difference between the two atoms of the C‑X bond would determine their relative contributions to the bond.

C and N, with the largest electronegativity difference, have the most polar bond. The bond can be considered covalent with some ionic character, as observed from the population analysis, where two‑thirds of the C‑N bond in [N(CH3)4]+ is attributed to N while one‑third is attributed to C. This is in agreement with MO principles, where electronegative atoms tend to have a larger orbital coefficient in bonding interactions and thus, contribute more to the bond. P and S, which are more similar to C in terms of electronegativity, have a smaller difference in contribution. S contributes to 50 % of the C‑S bond, while P contributes to 40 % of the C‑P bond. In the same way as observed in the C-N bond, this is due to S being slightly more electronegative than P, thus resulting in its marginally higher contribution to the C‑X.

By comparing these to the charge distribution calculated, it is seen that with decreasing electronegativity (N > S > P), the contribution to the C‑X bond decreases, and the charge distribution changes from negative, to increasingly positive. There is a direct correlation because a higher electronegativity would mean that the atom pulls more electron density towards it, resulting in a larger proportion of the C‑X bond being attributed to it.

It is also interesting to note the hybridisation on the central X atom and the C atoms of the methyl groups. N of [N(CH3)4]+ and P of [P(CH3)4]+ are both have about 25 % and 75 % contributions from the s and p orbitals respectively. This agrees with the conventional sp3 hybridisation that gives rise to the tetrahedral shape of the molecule. Conventionally, the S atom on [S(CH3)3]+ is also seen as sp3 hybridised but with a lone pair occupying one of the orbitals. Population analysis shows that the hybridisation is not perfectly sp3, and there is actually slightly more p character in the orbitals involved in the C‑S bond. The lone pair of S, on the other hand, was calculated to have almost equal contributions from the s and p orbitals, with 49.14 % s character and 50.85 % p character.

Part 2: Influence of functional groups

Optimisation

Optimisation on all compounds were done using 3‑21G first, followed by 6‑31G (d,p). The "nosymm" keyword was used in all calculations.

[N(CH3)3(CH2OH)]+

The log file for [N(CH3)3(CH2OH)]+ optimisation can be found here

The D-space link can be found here

Summary of calculation details

File type: .log

Calculation type: FOPT

Calculation method: RB3LYP

Basis set: 6‑31G (d,p)

Charge: 1

Spin: Singlet

Final energy: ‑289.39470840 a.u.

Gradient: 0.00000028 a.u.

Dipole moment: 3.80 Debye

Point group: C1

Time taken for calculation: 1 h 36 min 13.8 s

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000000 0.000002 YES

RMS Force 0.000000 0.000001 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000002 0.000006 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000001 0.000004 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.193071D-13

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

The calculations are complete as the forces and displacement have converged.

[N(CH3)3(CH2CN)]+

The log file for [N(CH3)3(CH2CN)]+ optimisation can be found here

The D-space link can be found here

Summary of calculation details

File type: .log

Calculation type: FOPT

Calculation method: RB3LYP

Basis set: 6‑31G (d,p)

Charge: 1

Spin: Singlet

Final energy: ‑306.39376154 a.u.

Gradient: 0.00000041 a.u.

Dipole moment: 6.79 Debye

Point group: C1

Time taken for calculation: 19 min 30.2 s

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000000 0.000002 YES

RMS Force 0.000000 0.000001 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000002 0.000006 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000000 0.000004 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-2.496288D-13

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

The calculations are complete as the forces and displacement have converged.

Frequency Analysis

[N(CH3)3(CH2OH)]+

The log file for [N(CH3)3(CH2OH)]+ frequency analysis can be found here

The D-space link can be found here

Summary of calculation details

File type: .log

Calculation type: FOPT

Calculation method: RB3LYP

Basis set: 6‑31G (d,p)

Charge: 1

Spin: Singlet

Final energy: ‑289.39470840 a.u.

Gradient: 0.00000037 a.u.

Dipole moment: 3.80 Debye

Point group: C1

Time taken for calculation: 22 min 2.6 s

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000001 0.000002 YES

RMS Force 0.000000 0.000001 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000002 0.000006 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000001 0.000004 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-2.586575D-12

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

Low frequencies --- -10.1362 -4.1239 -0.0012 -0.0010 -0.0007 9.3237 Low frequencies --- 130.8137 213.8884 255.5467

The low frequencies obtained are between ±15 cm-1. The calculation is complete as the frequencies obtained are positive, showing that a minimum point has been obtained.

[N(CH3)3(CH2CN)]+

The log file for [N(CH3)3(CH2CN)]+ frequency analysis can be found here

The D-space link can be found here

Summary of calculation details

File type: .log

Calculation type: FOPT

Calculation method: RB3LYP

Basis set: 6‑31G (d,p)

Charge: 1

Spin: Singlet

Final energy: ‑306.39376154 a.u.

Gradient: 0.00000048 a.u.

Dipole moment: 6.79 Debye

Point group: C1

Time taken for calculation: 24 min 41.0 s

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000001 0.000002 YES

RMS Force 0.000000 0.000001 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000003 0.000006 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000001 0.000004 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-2.341777D-12

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

Low frequencies --- -4.4911 -4.0174 -0.0010 -0.0006 0.0007 4.9455 Low frequencies --- 91.6004 153.8337 211.3004

The low frequencies obtained are between ±15 cm-1. The calculation is complete as the frequencies obtained are positive, showing that a minimum point has been obtained.

MO

The D-space link for [N(CH3)3(CH2OH)]+ MO calculation can be found here

The D-space link for [N(CH3)3(CH2CN)]+ MO calculation can be found here

HOMO-LUMO Analysis

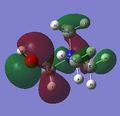

Shape of HOMO and LUMO

The LUMO of all 3 compounds look relatively similar, with a large portion of bonding interaction (green region) arising from the 2p orbitals on the various C atoms interacting strongly with each other. There is a node on each C atom due to the 2p orbital. As such, there is some through space antibonding interaction between the other phase of the 2p orbital (red region) and the rest of the MO (green region). H atoms are not involved, and the central N atom has a through space antibonding interaction between its 2s orbital and the 2p orbitals of the C atoms (green region).

In [N(CH3)3(CH2OH)]+, with the addition of an ‑OH group, there is an additional bonding interaction between one phase of the 2p orbitals extending from N, to C, to O (red region). The other phase of the 2p orbital then interacts with the rest of the MO in a similar fashion as in [N(CH3)4]+, contributing to the bonding interaction seen in the green region. As a result, there is an addition node on the O atom, giving rise to some through space antibonding interaction. The overall increase in antibonding character could contribute to the increase in energy of the LUMO as compared to [N(CH3)4]+.

In [N(CH3)3(CH2CN)]+, the same pattern is observed and the 2p orbital on the C atom of the ‑CN group forms a strong bonding interaction with the corresponding phases. This also leads to a node on the C atom of the ‑CN group and hence contributes slightly to the antibonding character of the molecule. The 2p orbitals on N, however, have strong through space antibonding interactions with the rest of the MO. In addition, there is a node on N arising from the 2p orbital. Similarly, the overall increase in antibonding character could contribute to the increase in energy of the LUMO as compared to [N(CH3)4]+.

As compared to the LUMOs, the HOMOs have changed much more drastically. In [N(CH3)4]+, the 2p orbitals of N and C take part in bonding interactions with each other and with the 1s orbitals of some H atoms. The antibonding interactions arise from the two opposite phases of the p orbitals, with a node on the N and C atoms. In this case, the MO is delocalised over almost the whole molecule.

[N(CH3)3(CH2OH)]+ and [N(CH3)3(CH2CN)]+, however, have much less delocalised HOMOs. Like [N(CH3)4]+, the main interactions are between the p orbitals of N, C, and O, resulting in nodes on the atoms and some antibonding interaction. Unlike [N(CH3)4]+, these orbitals do not have much interaction with the 1s orbitals of H.

In [N(CH3)3(CH2CN)]+, there is even less delocalisation of the MO as one of the methyl groups is completely not involved in any interactions. The main part of this MO is from the bonding interaction between the 2p orbitals of C and N of the ‑CN group, and the through space antibonding interaction between the ‑CN group and the adjacent ‑CH2 group. The antibonding interaction between the two adjacent groups gives rise to a nodal plane, while the 2p orbitals on ‑CN and the adjacent C lead to a node on each of the atoms.

Energy Level of HOMO and LUMO

Electron withdrawing groups generally tend to lower the HOMO and LUMO, while electron donating groups tend to raise the HOMO and LUMO.

This is observed when [N(CH3)3(CH2OH)]+ is compared to [N(CH3)4]+, where the energy of the HOMO increases from ‑0.57934 to ‑0.48763 a.u., while that of the LUMO increases from ‑0.13301 to ‑0.12459 a.u.. The HOMO-LUMO gap also becomes smaller, from 0.44633 to 0.36304 a.u..

In [N(CH3)3(CH2CN)]+, the energy of the HOMO increases from ‑0.57934 a.u. in [N(CH3)4]+ to ‑0.50047 a.u., while that of the LUMO decreases from ‑0.13301 to ‑0.18183 a.u.. The HOMO‑LUMO gap also becomes smaller, from 0.44633 to 0.31864 a.u..

The lower LUMO observed in [N(CH3)3(CH2CN)]+ is likely to make it more reactive than [N(CH3)4]+, especially in terms of electron acceptance. This also allows it to have better overlap with the HOMO of the molecule it is reacting with. In the same way, the higher energy HOMO observed in both [N(CH3)3(CH2OH)]+ and [N(CH3)3(CH2CN)]+ is likely to result in the molecule being able to donate electron density more easily.

NBO

Charge Analysis

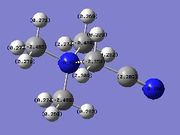

The colour range was set from -1.000 to 1.000 for comparison of charges based on colour across all three molecules. The colour range is from bright red, for most negative, to darker red, to darker green, to bright green for most positive.

When one H atom on a methyl group is replaced with an ‑OH group, as in [N(CH3)3(CH2OH)]+, the charge distribution on the central N atom changes from ‑0.295 to ‑0.322. This corresponds to an increase in electron density on the central N atom, and is expected due to the electron-donating behaviour of the ‑OH group. Being in between two electronegative atoms (N and O), the ‑CH2 C atom becomes relatively positive (0.088) as both atoms would tend to draw electron density towards themselves. The H connected directly to the O atom is the most positive as O is highly electronegative and draws most of the electron density towards it. The methyl groups further from the ‑OH group also experience a slight effect from the electron donation. The C atoms become slightly more negative and as a result, the H atoms bound to them become slightly more positive.

On the other hand, when replaced with a ‑CN group, as in [N(CH3)3(CH2CN)]+, the charge distribution on the central N atom becomes ‑0.289 as compared to ‑0.295 in [N(CH3)4]+. The charge distribution on the adjacent C atom also decreases from ‑0.483 to ‑0.358. This represents a slight decrease in electron density on the central N atom, and is attributed to the addition of the electron withdrawing group ‑CN, which draws electron density towards itself and away from the adjacent C atom and central N atom. The methyl groups experience a slight effect and become a little more negative, while the H atoms become a little more positive. It is worthy to note that for the ‑CN group itself, the C atom bears positive charge distribution of 0.209 while the N atom bears the negative charge distribution (‑0.186).

Conclusion

As observed from this small study of various cations, computational chemistry provides an alternative way of studying the properties of compounds. This is useful in studying ionic liquids where the many available combinations give rise to a wide variety of compounds which would be difficult to study efficiently using traditional methods. A useful feature is the ability to carry out the same calculations and hence, make comparisons across compounds simply by varying one component, such as the central atom (in part 1), or the substituent (in part 2). This would allow more convenient comparison and selection of ionic liquids for experiments as designer solvents.

Besides being able to predict IR spectra and allowing the MO diagram to be visualised, a useful feature of computational calculations is its NBO population analysis. It is interesting to be able to compare the relative orbital contributions of two atoms to a particular bond, and to compare this data obtained to the simplified orbital hybridisation studied previously. This allows greater appreciation of the complexity involved in the bonding in molecules.